Computer Applications in Veterinary Practice

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

1 Differentiate between operating software and application software.

2 Describe methods to research, select, and purchase hardware and software.

3 List routine maintenance needs for computer hardware.

4 Define the terms server, network, and database.

5 Describe the types of data included in the veterinary practice database.

6 List the advantages of computerized scheduling and name common features of scheduling software programs.

7 List the advantages of electronic medical records and describe common components of an electronic medical record.

8 Describe common features of inventory software systems.

9 Describe common features of billing software systems.

10 List and describe computer applications and websites related to veterinary research and education.

COMPUTER HARDWARE AND SOFTWARE

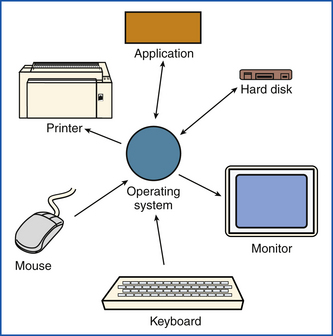

This discussion about the specifics of computer hardware and software assumes a certain amount of basic computer knowledge. Computer hardware relates to the parts of the system that you can touch: the monitor, the hard drive, the mouse, the printers, the modem, the disks, the scanner, and more (Figure 4-1). Software relates to the computer instructions contained within the hardware or added to the hardware. An important distinction should be made between operating software and applications software. The operating software tells the different parts of the hardware how to communicate with each other. For instance, the operating system translates strikes on the keyboard to letters seen on the screen. It monitors and organizes files and directories, and it controls peripheral devices, such as printers, scanners, and disk drives. Some commonly recognized operating systems are DOS, OS/2, Windows, Macintosh, UNIX, and LINUX. Application software is programs that help a user perform certain tasks. Some common examples of application software include word processing software, bookkeeping software, and practice management information systems.

FIGURE 4-1 This diagram depicts the function of the operating system and the flow of the information (direction) by and among peripheral devices.

Veterinary software products are becoming faster and more flexibile. The software programs offer users the ability to import results from certain laboratory equipment and allow multiple employees to manipulate data from different workstations simultaneously. Veterinary practice management software also provides a revision history feature. This means that all changes to the medical record are tracked. This is vital when considering a “paperless environment” in the event of litigation.

COMPUTER CONFIGURATIONS

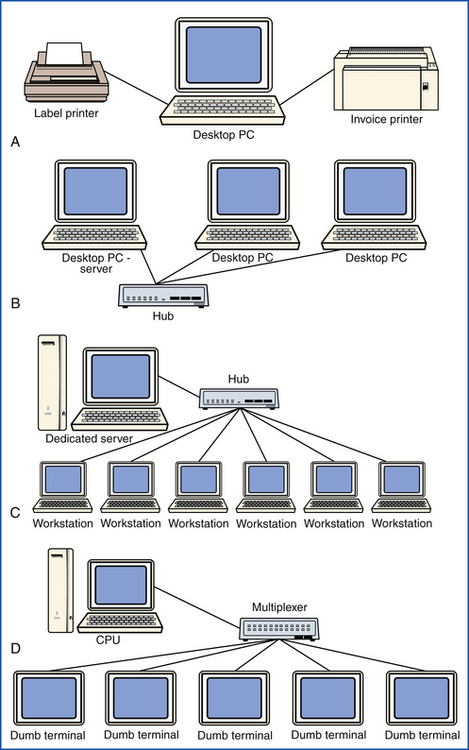

A solo veterinarian may require a computer terminal in the reception station, one in the pharmacy, one in the examination room, and one in the business and/or her office. These terminals would all be connected through a server, that manages the network of computer stations. The veterinary software is stored on the server in addition to the associated patient-client database. There are various configurations of networks found in veterinary hospitals depending on the complexity and functions of the system and on the needs of the practice (Figure 4-2).

FIGURE 4-2 A, Single station system. B, Multistation system with nondedicated server. C, Multistation system with dedicated server. D, A configuration with one central processing unit (CPU) and “dumb” terminals attached. PC, Personal computer.

Today’s veterinary environment supports many large practices staffed with general clinicians and specialists of various disciplines, multiple support staff, and a space occupying large square footage. In this type of setting, the above described network would not suffice. It is not unusual to see a terminal in each exam room, two to three terminals in the operating-treatment room, two to three terminals in the administrative offices, and two to three terminals in the reception area. Printers of differing types are scattered throughout these practices: a pharmacy label printer, a laser printer in reception, a printer for the bookkeeper, a printer for the administrator, and a printer in the laboratory. All of this hardware would be linked together through the network operating system, and the server manages the veterinary management software.

Recently, Tablet PCs have entered the veterinary arena. These are a type of notebook computer that has an LCD screen on which the user can write using a stylus. The handwriting is digitalized then converted to standard text. Tablets are wireless, affording the user the ability to take this technology wherever needed. Much of the information entered is accomplished through touching selected menus on the screen with the stylus. Many of the newer bundled packages come with supplemental software, such as anatomic diagrams, feeding recommendations, or drug formularies. With a touch to the screen, the staff can send home a patient health report card and customized client education materials while speaking with the client.

Do not avoid computerizing a practice or increasing the system’s capabilities for fear that medicine will become less personalized. These systems should enable better time management so that quality time can be spent with each client and better care can be afforded to each patient.

MAINTENANCE TIPS

Make sure the computer case has plenty of room. The microprocessor, the motherboard, and other parts of the hardware accumulate heat. Computer cases have a cooling fan and slots where the air can exit. Especially in a veterinary environment, make sure these slots are not clogged with hair and dust. Ensure that the computer is in an area with plenty of cool air.

Dust the computer case and monitor once a month. Dust left unchecked will find its way into the computer.

Clean inside the computer case every 2 to 3 months. This can be accomplished with compressed air (Figure 4-3). It may be wiser to contract a computer repair company to regularly perform this function. Even the smallest amount of static electricity can ruin vital parts of the hardware.

Regardless of the size of the system chosen, it is recommended that an electrical surge protector be provided for the system together with a battery backup. If not properly protected, vital information can be lost in the event of an electrical surge or a complete power outage.

Although initially expensive, it is wise to consider redundant (or mirrored) hard drives. When information is saved, it is saved to two or three hard drives. In the event that one crashes, at least one additional drive would contain all of the current practice information.

HOW TO RESEARCH, SELECT, AND PURCHASE HARDWARE AND SOFTWARE

When deciding to purchase a computer system for the veterinary practice, one must consider a number of factors.

• What is the flow of client traffic within the practice?

• What are the uses for the system?

After these questions have been answered, it is time to begin researching the various veterinary software companies. Most of the software programs available have similar features. The differences may be the ease of use, ability of the program to integrate with other equipment within the practice, and flexibility for the future.

The American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) publishes a trends survey every 2 years of what software programs are being used and how they are rated. In addition, many of the software vendors demonstrate their products at the national meetings. This is a great venue because you can compare and contrast different features of a number of competing products within one room. Contact the companies and discuss your needs. The vendors will assist you in deciding on what computer configuration is recommended to run their program and what the approximate costs will be. Some vendors also have demo CDs available so that you can investigate the program thoroughly.

Once you have narrowed down the search, there are some additional factors to consider:

• How long has the company been in business?

• How many systems have they sold?

• Can they provide references from practices employing this software?

• Are both hardware and software included in the support contract?

• What kind of staff training is provided and for how long?

• What is the anticipated cost of updates?

• If hardware is purchased from a separate vendor from the software, what support, warranties, and equipment loans do they offer?

As technology advances, it is reasonable for practices to replace hardware and/or software every 5 to 10 years. Although purchasing the components to computerize a practice is initially expensive, the following sections will demonstrate that savings to the practice will justify the costs.

TYPICAL USES OF COMPUTERS IN VETERINARY PRACTICE

The current trend in veterinary medicine is for veterinarians to practice as a group. Large practice groups offer veterinarians flexible schedules and no initial outlay of capital to establish a practice. As the client base of the practice grows, the number of veterinarians and support staff increases. This increase of human resources creates the need to manage information and communication between staff members, departments, and shifts. This trend would not be possible if veterinarians were not employing computers to help manage all of that increased information (Box 4-1).

DATA COLLECTION

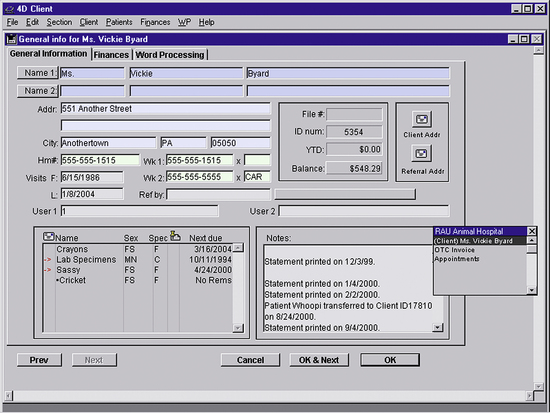

Data is simply pieces of information. When a client enters a veterinary practice for the first time, the receptionist asks them to fill out a new client-patient form with their personal information on it. This information will include their name, address, home telephone number, work telephone number, possibly even their e-mail address. All of this information, or data, is keyed into the computer. The form will ask for information regarding the patient: pet name, species, breed, age, color, etc. The receptionist will also enter this information, thus creating a virtual record for that client and patient (Figure 4-4).

As the client moves from the waiting room to the exam room, the technician continues to gather information. The weight of the patient is obtained and entered into the patient record. Any past inoculations and the dates last administered are entered into the record. Any past medical problems will be keyed into the computer. This data is stored in a database.

Through a query screen, the user can request a patient’s record by a variety of parameters: client last name, patient name, telephone number, or address. If the last name of the client is a common one, such as Smith, the computer would produce a long list. In that case, it would be easier to change the query parameter to Patient Name and enter the name, “Sassy.” The result will be a shorter list of all of the patients in the database by that name.

Data collection is important in a multitude of ways. The computer is capable of producing a list of all patients that are due to be inoculated in the month of June in the year 2008. This list can be used to produce the vaccination reminders that are to be mailed out, thus prompting next year’s appointments.

The computer can produce a list of all patients that received recommendations for dentistry. It can even identify the practice’s top 1000 income-generating clients so that you can send them the practice’s newsletter. All of these functions can be accomplished in a matter of minutes with the use of a computer compared with the amount of time it takes to generate any of these lists by hand.

SCHEDULING

When evaluating veterinary software, an important feature is the appointment scheduler. When the appointment book is not computerized, only one staff member can manipulate the schedule at a time. Computers make it possible for multiple staff members to be able to add or delete appointments concurrently. The veterinarian can schedule an appointment while speaking to the client, and the technician can schedule a recheck appointment while discharging the patient from surgery. Ideally the appointment schedule should be available at a variety of workstations. This feature alone decreases the chaos at the front desk created when all client contact requires a receptionist.

Some veterinary software synchronizes the appointment scheduler with the client-patient medical records. When you are in the patient record, a drop-down menu will offer a link to the appointment scheduler. When a time and date are selected, the patient name, client last name, and telephone number is automatically put in that slot. Another element of a computerized appointment scheduler is the “find next appointment” feature. If a client has forgotten when his or her appointment is scheduled, the receptionist may enter the patient record, drop down a menu, gain access to the appointment scheduler, and select “find next appointment.” The computer will then search and display the appointment. This would be a tedious task without the help of a computer.

Some appointment schedulers are capable of appointment time customization. Identified tasks can be assigned specific lengths of time. Instead of scheduling a standard 15- or 20-minute appointment for suture removal, it could be customized to a 5- or 10-minute appointment. Some schedulers track and identify clients that have missed previous appointments. This enables the reception staff to confirm those appointments with a telephone call.

Seventy percent of all scheduled appointments are generated from reminders. Some powerful veterinary software will display vaccine alerts prompting multiple pet visits, rather than just scheduling the appointment driven by the mailed reminder.

BILLING

Older systems depend on the use of a “travel sheet.” This is a sheet that has a list of line items on it. The term line item refers to any product or service within the practice that has a price attached to it. As services are rendered, the staff member highlights the line item on that patient’s travel sheet. At the end of the day, a staff member enters those line items into the patient’s invoice.

Systems that employ the use of a “travel sheet” inevitably lead to lost income. Traditionally, these are two-sided sheets, and it is possible in a rushed moment to forget to input charges highlighted on the back. It is easy to forget to highlight a product dispensed. It is not unusual for there to be a $20,000 to $50,000 loss of income per full-time veterinarian per year with charges that are not captured.

With newer veterinary software, as staff members perform medical tasks, they enter those services directly into the computer. An invoice is created as a patient enters the practice. When the veterinarian examines a pet, they enter a code for “office visit.” A window then opens for them to enter their SOAP notes. When they close that window, they select a code for the next service (e.g., “in-house serum chemistry and CBC”). The veterinary software handles updating the invoice. As the services increase, so does the invoice.

Veterinary software does not come with predetermined prices of products and services. As the software is introduced, the administrators of the practice input set prices for each service or product. When computers were not employed, veterinarians were aware of the costs to the client. They tended not to charge for services out of a sense of guilt and/or discomfort. Invoice totals were lower, thus cutting the profit to the practice. With the use of advanced systems, the staff is less aware of the prices accruing as they render medical treatment. This feature alone is largely responsible for practices being able to afford more professional staff, thus increasing the standard of care and decreasing staff burnout.

MEDICAL RECORDS

Chapter 5 specifically discusses medical records. The discussion here is meant to highlight the benefits of electronic medical records.

In the past, when medical records were made of paper, only the person handling the record could gain access to the information. With computerized medical records, staff in different rooms of the practice can see the information simultaneously.

Paper medical records could be found in a variety of places: in the file, in a stack of records awaiting communications, in a pile of records on the bookkeeper’s desk, in a pile waiting to be refiled, or even in a box in the attic as a result of inactivity. Because paper medical records “walk,” they are often difficult to find. Computers allow us to retrieve vital information immediately.

Computerization has also improved the quality of the information. The information is legible and more organized. With the use of templates, the different parts of the exam are listed, defaulting to “nothing abnormal seen.” When notable findings are made, the veterinarian can either type in the information or select a finding from a menu.

It is also true that many veterinarians are not typists. Voice recognition software is not out of the realm of possibility within the near future. The medical findings are spoken into a microphone, which then translates the sound of a voice into words on a word processor. These notes can then be cut and pasted into the medical record.

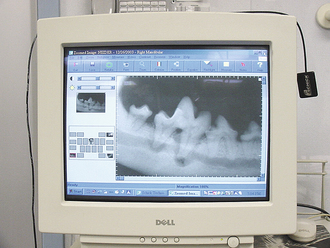

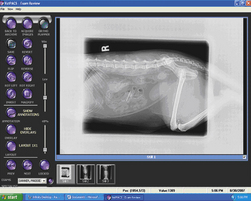

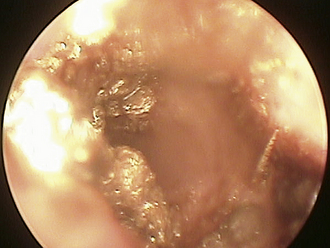

Advanced veterinary software permits documents, such as referral reports, electrocardiogram strips, radiographs (Figure 4-5), photos (Figure 4-6), and more to be scanned or imported directly into the patient’s medical record. This reduces staff time searching for reports, pulling radiographs, and subsequent refiling.

FIGURE 4-6 A digital image of an ear canal before an ear flush. This image was obtained with a video otoscope.

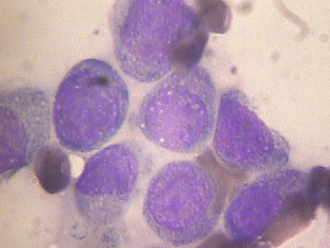

Some programs are capable of maintaining a digital photo of the client on the record. Upon retrieval of the patient file, there may be a photo of the patient. A digital camera can be used to take images of lesions or teeth (Figure 4-7), or it can be attached to a microscope for images of cytology or hematology slides (Figure 4-8). These images can be imported right into the patient’s electronic medical record for future use or e-mailed to a referral specialist.

CLIENT COMMUNICATIONS AND MASS MAILINGS

As discussed in the Data Collection section, information that is entered into the record can be retrieved later for marketing purposes. Vaccination reminders are printed and mailed out monthly. Recommendations made in patients’ records can be tracked. The practice can then prepare and send mass mailings extolling the benefits of senior-wellness packages, dental cleanings, and other services. Once the list is created, address labels can be printed, and new business is only days away.

INVENTORY MANAGEMENT

With most veterinary software, inventory management is a module of the program. Because the nature of practice, this module of veterinary software is not without its problems. If all of the inventory for the practice was ordered, received, stocked, prescribed, and sold, the inventory management would be easily handled by the computer. Unfortunately, catheters, tape, syringes, needles, cleaning supplies, and sterilization supplies constitute items that are used within the practice on a regular basis, but are separately billed therefore making them difficult to track. Not every intravenous catheter attempt is successful, yet the client is only charged for one. Dispensable items, such as medication, food, shampoo, etc., can be tracked. Levels can be set within the system, and weekly order reports can be generated by the computer as levels get low. Presently, computerized inventory management is almost always coupled with a manual system for all usable items.

ACCOUNTING AND PRACTICE MANAGEMENT

As medical services are added to the medical record, charges are added to the invoice. When the receptionist cashiers out the client, the payment is recorded on the invoicing-payment screen. If there is a balance on the account, the veterinary software keeps track of the accounts receivable.

The practice administrator sets a time within the system when accounts are considered overdue (30 days, 60 days, and 90 days). Monthly bills can then be sent out to all past due accounts. The software is also capable of adding a late fee depending on the length of delinquency.

Today’s software also makes it possible to block a client from charging fees in the event that they are habitually negligent in paying their bills. Without alerts and blocks, accounts receivable could get prohibitively high.

Another aspect of the veterinary software is the ability to track income production for each veterinarian. Some practices pay their veterinarians a base salary plus compensation based on production. As entries are made within the medical record, the veterinarian that ordered the service is credited with the production of that fee. Even if the veterinarians are not compensated for production, this gives management valuable information. For instance, if Drs. A and B are able to produce a consistent percentage of the gross annual income by generating dentistry but Dr. C’s production is much lower, management can have an educated discussion about making appropriate recommendations for care.

Practices will need to supplement with separate accounting software to complement the data gathered within the veterinary software. Products such as Peachtree Accounting or QuickBooks are commonly used. Bookkeepers input information gained from the billing and invoicing features of the veterinary software to manage the financial aspects of the business. This financial software manages accounts payable, prints checks, and tracks expenses. It tracks financial information and prepares tax information for the accountant. There are even programs currently available that allow practices to handle all of this online.

Accounting software, whether it is part of the veterinary software or a supplemental software package, is essential for evaluation and management of the practices’ profit centers. Profit centers are specific components of a practice that generate income. For instance, boarding is a profit center within the practice. There are costs incurred by the practice to provide boarding services, and there is income generated. Evaluation of the profit-to-loss ratio aides practice managers in decisions regarding that profit center (i.e., staffing, equipment, supplies, etc.). To attempt to get this information without the use of a computer would be difficult and time consuming.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE FUTURE

The term paperless applies to a business that manages all of its information on one computer system. Currently, most veterinary practices are considered to be “less-paper” practices rather than “paperless.” The typical computerized veterinary practice still generates literally tons of information on paper and media that are not being stored in the computer. X-rays, consent forms, travel sheets, time cards, faxes, admission forms, referral letters, anesthesia-surgery logs, controlled substances logs, etc., are all still produced on a daily basis. A paperless office is not a pipe dream any longer. Scanners and CD-Rom technology are readily available and affordable. Information stored electronically is safer than printed media. Ten CDs can store approximately hundreds of thousands of documents. All of that information can easily be carried out of the practice and stored off of the premises. The loss of information in the event of a fire can be catastrophic in a conventional veterinary setting.

Some practice managers hesitate to convert to a paperless system for legal reasons. To date, it appears that no paperless case has gone to court. Yet the concerns are that medical records must be protected from alteration afterward. Proof of electronic medical record security can be provided by backing up the records on a monthly basis and storing them with a data storage facility. Comparison can then be made by the court that both copies match, ensuring the information contained within has not been corrupted.

OTHER APPLICATIONS FOR COMPUTER USE IN THE VETERINARY PRACTICE

The previous sections involved discussions about the software available to manage many of the business aspects of veterinary medicine. Technicians will find that computers will play an ever increasing role in their daily professional lives.

Continuing education is a good example. There are websites on the Internet dedicated to providing technicians a venue to ask questions, research information, read recent publications, and have direct access to specialists in the field. Some popular sites for technicians are:

• www.VetMedTeam.com (Figure 4-9)

FIGURE 4-9 The VetMedTeam.com homepage.

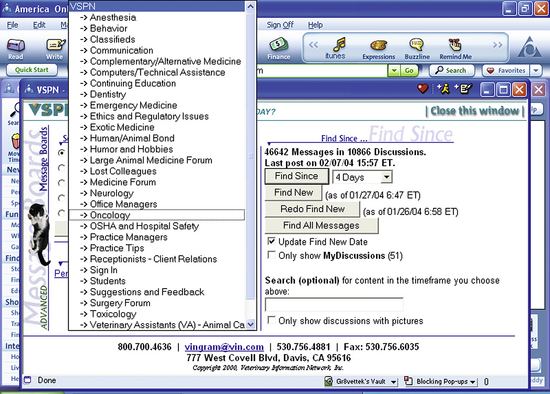

• www.VSPN.org (veterinary support personnel network) (Figure 4-10)

FIGURE 4-10 This shows the VSPN.org list of message boards in which technicians can participate.

These sites require no more than a brief registration form ensuring the site that you are a technician or a technician student. They are free and encourage your participation and professional growth. Both sites have message boards on every discipline: anesthesia, animal behavior, avian and exotics, clinical pathology, dentistry, emergency and critical care, practice management, and other topics. They both have libraries with search engines to narrow the information search. Both sites offer classes for continuing educational credits (fee associated), and both have chat rooms used for classes.

There are other veterinary-related websites:

• www.avma.org (American Veterinary Medical Association [AVMA])

• www.vin.com (Veterinary Information Network)

The AVMA site is open to anyone who wants to visit the site, including pet owners. There is a special section of the website called NOAH. Access to this area is gained with a membership number (dues required) and a password. Vin.com is a site “for veterinarians by veterinarians.” There are membership costs for veterinarians, and technicians are not permitted on this site. VSPN.org is the technician subsidiary of this site.

These sites are all beneficial because they offer veterinary professionals a means of discussing cases and sharing information. Each message board is monitored or edited by veterinarians or technicians that are either board certified specialists or hold a certain degree of expertise in a given discipline.

It is not unusual to see digital photographs of lesions, unusual ECG strips, even digital radiographs posted within a discussion. This technology brings the case before many people from all over the world to gain varying ideas and options regarding treatment plans. The caveat to any information obtained on the Internet is this: there are no governing bodies regulating what is written or said on the World Wide Web. These websites have disclaimers reminding the reader that, regardless of the recommendations, the veterinarians are ultimately responsible for the care of their patients. Consider and confirm the information read on the Internet before employing it.

THE FUTURE IS NOT FAR AWAY

All of the discussed technology costs the practice money. But money invested upfront provides a greater return on investment in the long run. Some of the equipment available today for veterinarians is:

• For capturing images of lesions, teeth, etc.

• An affordable means of capturing and organizing dental radiographs

• DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) technology: a standard for handling, storing, and transmitting medical imaging. DICOM images can only be transmitted to entities that can receive DICOM images. The image will contain the patient’s data, such as patient ID, so that the information about the patient and the image can never be separated.

Let us consider some of the ways that computer-related technology can help us provide more efficient and cost-effective medical care for our patients. In the following cases, practice A has various computer-related technologies, practice B does not.

1. A cat is admitted to practice A because of a misaligned bite. Practice A does not have a board certified veterinary dentist on staff. Instead, they take digital photos and digital radiographs and e-mail these images to a specialist. Within hours, practice A has heard from a board certified veterinary dentist as to whether or not referral holds any benefit to the patient. Practice B would have to copy and send the medical records along with the patient to the specialist for evaluation. These appointments can take weeks to months to obtain.

2. Practice A has provided training for technicians to obtain sonographic video images. These images can either be sent via the Internet to a medical consulting service, such as DarkHorse Telemedicine or a radiologist can come into the practice to review the tapes and provide diagnoses. Practice B will have to refer the patient to another practice that can provide these services.

3. Practice A can obtain images from cytology slides (see Figure 4-6) and maintains the images in a file. The samples are sent to an outside pathologist for review. When the report returns, the diagnosis is added to the file for educational purposes within the practice. Practice B does not benefit further than the diagnosis itself.

4. Images of lesions are captured and maintained in practice A for comparison. This enables different veterinarians within the practice to evaluate progress without having to be present initially. Practice B requires appointments to be made with the same veterinarian, regardless of scheduling conflicts.

5. Practice A wants to research new pain management protocols for their canine patients. They get on the Internet and gain access through Vin.com. They enter canine and pain management in the search engine, and 80 documents relating to dogs and pain control are revealed. These documents include discussions on message boards, journal articles, conference proceedings, and clinical resources. After perusing these documents, they have had the ability to read what veterinarians all over the world are prescribingfor their canine patients. Practice B will have to register for an upcoming continuing education lecture on the subject, read an outdated textbook, or order a new one.

These examples demonstrate how computer-related technology can maintain your patients within your practice, save time and stress to the client and patient, and overall increase revenue.

Veterinarians and technicians are surprised daily with educated owners that have researched their pet’s symptoms or disease online and come to their office visit with educated questions for the staff. It is obvious that the World Wide Web or the Internet has an impact on our daily lives.

Technicians tend to pursue the veterinary field to work with animals, to help the patient’s families, or because they have a keen interest in the field. The technicians that are willing to invest the time in keeping current with technology will clearly have an edge.

TECHNICIAN NOTE

TECHNICIAN NOTE