Medical Records

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

1 List and describe the primary and secondary purposes of the medical record.

2 Differentiate between letter-size, card file, and carbonized sheet medical records.

3 Differentiate between source-oriented and problem-oriented medical records.

4 List and describe the components of a problem-oriented veterinary medical record.

5 List the information recorded on a patient’s medical history.

6 Define the SOAP process and explain the types of information included in each portion of the SOAP record.

7 List and describe the types of forms and logs commonly used in veterinary practice.

8 Describe the requirements of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse and Control Act.

9 List and describe the types of filing systems commonly used in veterinary practices.

10 Describe the ethical and legal issues related to the ownership of medical records, release of medical information, and maintenance of medical records.

FUNCTIONS OF THE MEDICAL RECORD

The Institute of Medicine has organized the functions of the medical record into two broad categories: primary purposes and secondary purposes. Primary purposes support the patient’s medical care, such as the documentation of diagnostic procedures, diagnoses, prognoses, and treatment. Secondary purposes are not clinically based, but include evaluations of medical information for business, legal, and research purposes.

PRIMARY PURPOSES

Supports Excellent Medical Care

The medical record is a critical tool that enables and supports the effective treatment and care of animals, and it does this in many ways. First, it assists the veterinary health care team in correctly identifying the patient and the owner. There are, after all, many black Labrador retrievers that look alike and many owners named Smith, Jones, or Brown. In this way, the medical record helps to prevent confusion of the identities of the patients and their owners. Second, it helps in the generation of an effective diagnostic and treatment plan. It documents the veterinarian’s physical examination findings, lists the diagnostic procedures and tests to be performed, and records the veterinarian’s ideas regarding differential diagnoses. The medical record also enables practitioners to document the patient’s responses to treatment, so plans may be adjusted as needed. As time passes and members of the health care team change, the medical record supports continuity of care. It helps practitioners, who are not familiar with the patient, to understand the medical history and conditions of the animal. In this way, it provides an avenue for communication between each of the members of the veterinary health care team so that treatment can be accurately and effectively administered.

Documents Communication

The medical record also documents communication with the client, which is particularly important when there are many members of the veterinary health care team assisting the same client. Take-home instructions, for example, will be included in the medical record, so any confusion about home care by the client (owner) can be quickly clarified. In addition, the medical record assists in the generation of reminder cards that help pet owners to stay current in their pet’s preventive medical plan. In these ways, good communication is critical for providing a logical, continued plan of patient care for both the health care providers and for the pet owner.

Interactions with clients and their pets are also aided by the use of medical records. Financial limitations, for example, and the behavioral idiosyncrasies of the pet may be recorded. In addition, the veterinarian-client relationship can be further enhanced when the names of other family members and important family activities are noted in the record as reminders for future topics of informal discussion.

SECONDARY PURPOSES

Supports Business and Legal Activities

The medical record lists all of the services rendered to the pet owner, whether it is boarding a dog or spaying a cat. This documentation verifies billing and serves as legal evidence of services received by the owner. It can be used to assess the workloads of staff members, formulate income analysis, make budgetary plans, perform actuarial calculations, maintain inventory, and generate a marketing strategy. In addition, it plays an important role during hospital accreditations and helps assess compliance with standards of care.

The medical record is used as a legal document in a court of law and is valuable during litigation. It serves as evidence of procedures performed and treatments administered, and it provides specific dates and times of events. In this way, the medical record is critical in defending against malpractice suits. Special care must be taken to ensure that the record is complete and accurate. Keep in mind that in a court of law, the prevailing view is “not recorded, not done.” In addition, insurance companies may require the medical record to assess whether a claim is to be paid.

Supports Research

The medical record is a key element in the preparation of case studies and presentations for conferences. Information from medical records is collected to develop registries and databases, which assist in the conduction of retrospective studies and in predicting clinical outcomes. It is used to teach veterinary medical and veterinary technician students. To maintain confidentiality, all patient markers are removed from the record before they are used for any purpose other than patient care (Box 5-1).

TYPES OF PATIENT RECORDS

With use of computers and veterinary practice management software, veterinary hospitals are managing information better and more efficiently than ever before. However, the vast majority of practices continue to employ hard copy, paper-based medical records in addition to using computers. This chapter concentrates on the written record, whereas Chapter 4 concentrates on the digital record and the use of computers in information management.

Medical records come in a variety of shapes and sizes. They typically appear as letter-size folders that contain a variety of forms and charts held in place by fixed clips. However, they can also come in the form of large index-type cards on which the veterinarian makes handwritten notes. In addition, ambulatory food or equine practices often carry simple carbonized forms that serve as both a record of the services rendered and the charges assigned. Let us examine each type of medical record in greater detail.

LETTER-SIZE FOLDERS

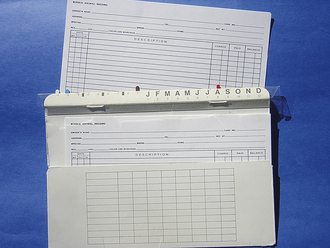

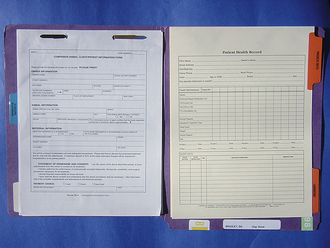

The vast majority of veterinary practices today make use of 8- × 10-inch folders in which medical information is stored and organized (Figure 5-1). Each patient has its own folder. Tabs are located at the edge of one end of the folder to facilitate the placement of color-coded decals. Some folders have grids printed on the outside of the cover on which critical information, such as the animal’s immunization history, can be written. In this way, the staff can quickly visualize key pieces of information. More commonly, however, veterinary practices use folders with a plain Manila cover.

FIGURE 5-1 Shown are a variety of letter-size folders. The color and style of the folders can vary in addition to whether charting is stamped on the cover. Color-coded decals are placed on the edge of the folders to facilitate filing.

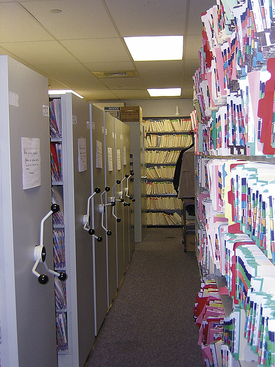

Letter-size folders are typically stored vertically on shelves, which are kept behind or near the receptionist’s desk for easy retrieval. Some particularly large practices may have record rooms in which a mobile shelving system may be employed. In these systems, large shelves are mounted on tracks so that they can be moved easily from one location to another when pushed. Mobile shelving systems save space because shelves may be positioned up against one another when access to their records is not needed (Figure 5-2).

CARD FILES

To conserve space and cost, some veterinary practices use a card file system instead of maintaining letter-size folders. One type of card used is 5 × 8 inches, which is stored in a file pocket (Figure 5-3). Laboratory data and other reports can also be stored in the pocket with the animal record. As more and more writing space is needed, additional cards can be stapled to the original card. If a family has more than one animal, there is a separate card for each patient, but the cards are often clipped together and filed as one unit.

FIGURE 5-3 The card-style record with pocket folder, though once popular, is not as commonly used as the letter-sized folders.

Another card system involves the use of a 10- × 16-inch card, which can accommodate more information per card than the 5 × 8 system. The 10- × 16-inch card can be folded in half to facilitate handling.

Card files are typically stored in file drawers rather than on shelves and are generally organized in alphabetic order according to the first letter of the last name of the client.

A plastic strip along the top of the folder contains a letter for each month and numbers that help receptionists to keep track of when reminder cards should be mailed. In addition, the strip contains hooks that enable the file to be suspended on a rack in the file drawer.

As a result of their small size and limited writing space, information contained on cards is brief. The patient’s information is usually entered in reverse chronologic order. The date and information regarding each appointment is entered on a separate line. Each card file must contain the owner’s and patient’s information along with sufficient data to allow the proper and adequate care of the animal. However, in our modern, litigious society, keeping thorough and complete records is increasingly more important because detailed medical information is often requested in a court of law. In addition, practices seeking accreditation by the American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) are required to use letter-size folders. For these reasons, cards, though once popular, are not as commonly used today because letter-size folders can accommodate a more comprehensive animal health record.

CARBONIZED SHEETS (AMBULATORY LARGE ANIMAL PRACTICES)

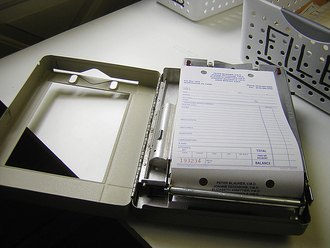

Ambulatory food animal and equine practitioners work long hours and put many miles on their trucks as they travel from farm to farm (Figure 5-4). The use of lengthy medical records is impractical in a situation where there is little storage space (in the truck) and where paper might blow out the window. Many ambulatory practitioners make handwritten notes on carbonized invoice sheets that are loaded into a sturdy metal dispenser (Figure 5-5). Once procedures are performed, diagnostic and treatment notes and billing information may all be included on the invoice pages. A copy is given to the owner. Information from the sheets is typed into the computerized record keeping system at the practice’s home office. A veterinarian who spends long days on the road might joke that this system is in keeping with the “Veterinary Medicine Paperwork Reduction Act,” but it is also cost-effective and practical. Throughout the year, but particularly in the spring, during lambing and foaling season when practitioners receive remarkably little sleep, the carbonized sheets provide adequate documentation and communication in a time-efficient manner. This helps the veterinarian meet the heavy demands of ambulatory practice.

FIGURE 5-5 The carbonized billing sheet also serves as an accounting of the treatments performed during a farm call.

Many veterinarians have begun to use laptop computers in the trucks to assist with record keeping. In this situation, the practitioner enters diagnostic, treatment, and billing information into a portable laptop computer that can be plugged into the cigarette lighter or run on batteries. The data can later be transferred to the practice’s networked computer system when the veterinarian returns to the office to restock the truck. Some ambulatory practitioners use an index of bar codes, each one representing a different diagnosis, procedure, or medication. The veterinarian scans the appropriate bar codes to create an invoice and to document the diagnosis and treatments rendered. Instructions to the owner might also be generated. A small portable printer carried in the truck would enable the document to be printed on-site and subsequently given to the owner. Wireless capabilities are also being explored by some progressive ambulatory practices.

It is impractical for food animal veterinarians, who are responsible for the health of entire herds of livestock, to maintain an individual record for every animal treated. In this situation, records are kept on the herd as a whole. Immunizations and reproductive histories are maintained for the group, although individual records may be generated for animals that have undergone special surgical or treatment procedures.

Large animal teaching hospitals and full-service equine practices commonly have hospitalized surgery, medicine, and neonatal patients and often employ the standard 8- × 10-inch file record system. In this situation, each patient has its own medical record. In-house treatments and procedures are recorded in the record by hospital staff members. An invoice is generated separately and is typically given to the owner for payment before the animal is allowed to be discharged and loaded onto the trailer.

FORMAT OF THE PATIENT RECORD

As mentioned, veterinary medical records are not subject to the federal and state regulations that one sees in the human medical field. Therefore there is a wide range of approaches to record keeping, which vary from practice to practice. Most methods, however, fall into one of three categories:

1. Source-oriented medical record (SOMR)

2. Problem-oriented medical record (POMR)

3. Combination of source- and problem-oriented medical records

SOURCE-ORIENTED MEDICAL RECORD

The source-oriented method is typically used in records that have limited space, such as in the card- or pocket-type records. Information comes from various sources and is entered chronologically by office visit or period of hospitalization. In this way, the most recent information is located last. Typically the date is entered in the far left-hand column of a line on the card, and the entry is made to the right of that. Physical exam findings, the database, diagnoses, and treatments are all listed. The veterinarian often makes entries in a “free form” that integrates information from various sources as it becomes available or comes to mind. The source-oriented method is easy to learn and takes little time to complete; however, it can lack detailed documentation, which may prove vital during litigation. Remember, “if it is not written down, it didn’t happen.”

PROBLEM-ORIENTED VETERINARY MEDICAL RECORD

The problem-oriented veterinary medical record (POVMR) is used in conjunction with the folder type of medical record and is used in teaching hospitals, AAHA-accredited hospitals, and many private companion animal practices, including specialty and emergency centers. The format helps to provide a whole view of the patient and supports a logical and organized approach to clinical medicine. It fosters excellent communication, team-oriented medical care, and rapid retrieval of information. Veterinary teaching hospitals find the POVMR particularly helpful when veterinary medical and veterinary technology students first learn to approach medical cases. The format provides a structured way to walk students through complicated cases, one problem at a time. In addition, a requirement for AAHA-accreditation is use of the problem-oriented format.

Though the components of the POVMR can vary somewhat, it most commonly includes the following:

1. Client and patient information

4. Master problem list and working problem list

5. Progress notes, assessment, and plan

6. Pertinent forms: surgery, anesthesia, radiography, special imaging, and laboratory reports

These components can be further subdivided into more specific units of information (Box 5-2).

COMPONENTS OF THE POVMR

CLIENT AND PATIENT INFORMATION

Typically the receptionist first takes the name, address, and telephone number of the client when the first appointment is made. This information is confirmed later when the owner arrives for the appointment. It is particularly important to record the correct spelling of the owner’s first and last name. Even seemingly simple names such as Megan Brown may be spelled Meaghan Brown or Meghan Browne. Do not assume to know the correct spelling of the client’s name; always confirm it. This will prevent subsequent filing and client-identity errors.

Cell phone numbers and e-mail addresses of the owner may also be important to obtain when the owner is in the office. In addition, the receptionist might want to have a general idea of the client’s schedule for the day and where he or she can be reached at what time. This is particularly critical if the pet is undergoing surgery or a procedure that requires anesthesia. Unexpected events or findings can occur during clinical procedures, and the veterinarian may need to consult the owner immediately. Sometimes the owner must make important decisions over the telephone, such as the extent of treatment to be performed, while the animal is on the surgery table and/or under an anesthetic. In this situation, good communication and care for the patient is maximized if the client can be contacted.

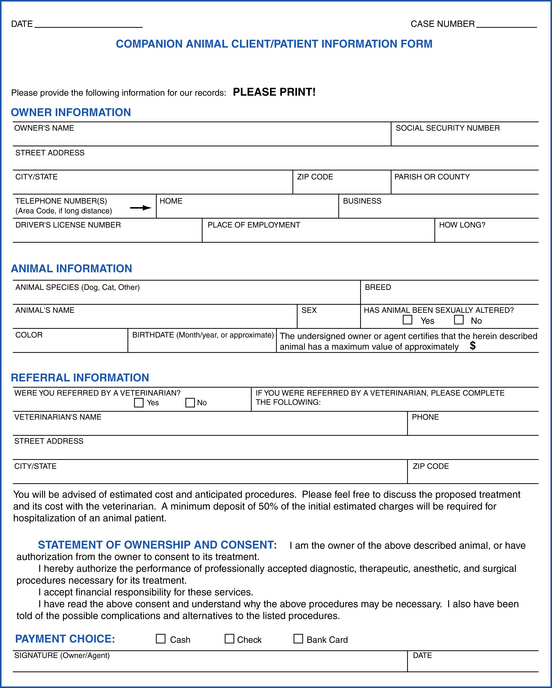

In addition to the client information, the receptionist also records the age, breed, sex, and species of the patient. This information is collectively known as the signalment. In some veterinary practices, it is imprinted, together with the client information, on the top of each medical record form using a plastic hospital card. When using a wide range of forms, as is done in many veterinary teaching hospitals, it is important to always remember to stamp each and every form. Refer to Figure 5-6 for an example of a client-patient information form.

The signalment of the patient is the first critical bit of information that helps the veterinarian in problem solving. Cancerous tumors, for example, are less likely to occur in puppies than in older dogs. Similarly, congenital abnormalities, such as a cleft palate, are often first noticed in young animals, so it is rare to first diagnose them in older animals. Similarly, there are certain conditions that are typically seen in large breeds of dogs and rarely seen in small breeds. Disorders may typically be seen in cats, but not in dogs. In this way, the signalment immediately assists the veterinarian to hone in on certain disorders and rule out others.

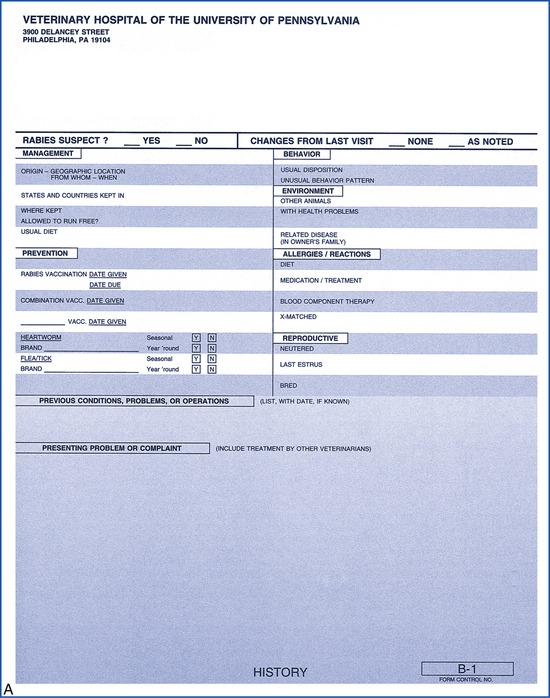

HISTORY FORM

A comprehensive history includes both previous and recent history information. It is typically taken during each new-patient visit and during visits from those patients that have not been seen in several years. Some practices have two history forms: one in which the previous history information is recorded and the other for recent history information. Figure 5-7, A shows an example of a history form in which both the previous and recent history information is recorded together.

FIGURE 5-7 A, Example of a comprehensive history form. B, This physical examination form is printed on the back of the comprehensive history form shown in Figure 5-5.

Previous history information includes the following:

1. Origin: animal’s birthplace and date

2. Preventive medicine program: immunizations, parasite control, dental care program, ear care program

3. Behavior: usual disposition and temperament, unusual behavioral events

4. Environment: kept indoors or outdoors, presence of other pets in the home, level of exposure to non–family-owned pets, travel history

5. Known allergies and reactions: atopy, food, contact with substances, medications, blood transfusions

6. Reproduction: neutered, estrus cycles, when bred, number of litters

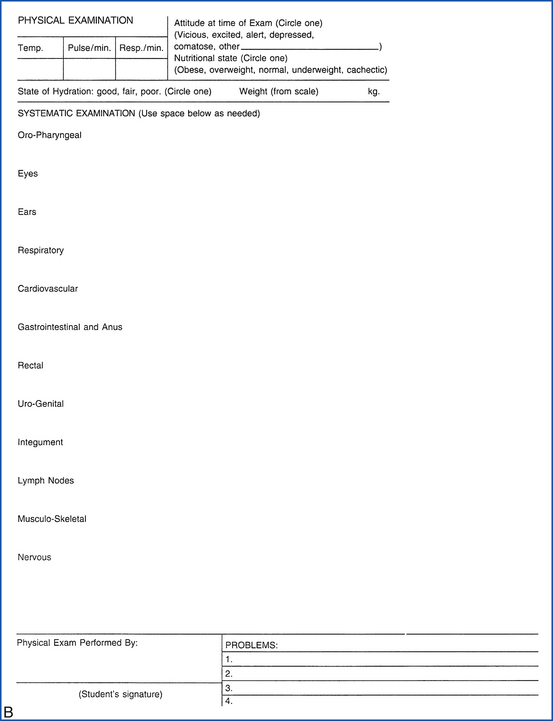

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION FORM

The physical examination is one of the most important diagnostic procedures and, if performed carefully and systematically, can provide the clinician with the critical information that ultimately leads to a diagnosis. The physical examination form is structured in such a way as to help the veterinarian and the veterinary technician to examine each anatomic system without overlooking anything. Notes are made directly on the form. “WLN,” for example, may be written, which means “within normal limits,” or “B & A” may be written, which means “bright and alert.” There is a wide variety of abbreviations that clinicians use when completing medical record forms. Refer to Figures 5-7, B and 5-8 for examples of a physical examination form.

DATABASE

In the POVMR, the signalment, history, physical examination, and diagnostic tests are collectively known as the database. The database forms the foundation of information on which veterinarians are able to make their diagnoses and therapeutic plans. Each veterinary hospital, however, may have its own variation on the standard database. Animals admitted for either a routine visit or a hospital stay may have, for example, a complete blood count, urinalysis, and fecal analysis. In this way, the database can vary depending on the needs of the patient. The tests done on the first visit will be considered the original database, and any subsequent visits should provide data for current problems.

In many emergency and critical care units, the database is considered to include five or six important pieces of information that are key in treating the critical patient. These include the: packed-cell volume, total solids, potassium, blood urea nitrogen, dextrose, and urinalysis. These data can be acquired quickly with a small amount of blood, a countertop centrifuge and analyzer, and dipsticks.

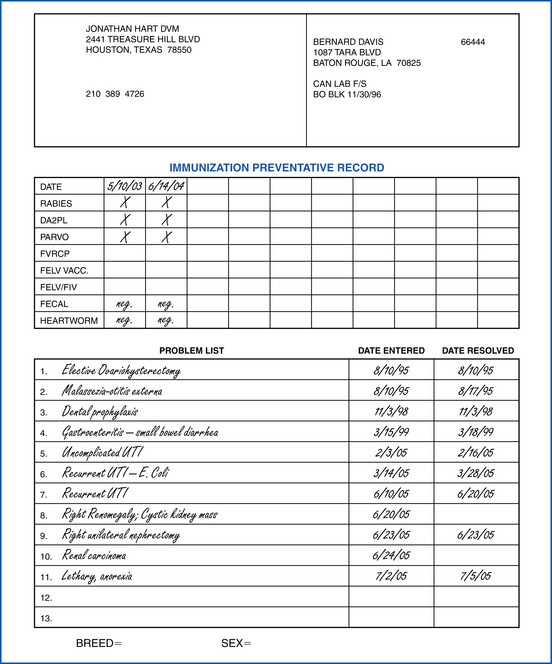

MASTER PROBLEM LIST

A defining part of the POVMR is the problem list. The master problem list includes the major medical disorders experienced by a patient during its lifetime. These medical problems are listed in chronologic order, and a date is noted when and if they are resolved. In this way, the master problem list serves as a snapshot overview of the patient’s medical history. At a glance, the clinician can determine what happened, when, and how long it lasted. See Figure 5-8 for an example of a master problem list. A summary of the preventive medical history may accompany the master problem list, which includes the dates when immunizations were administered and the results of fecal analysis and feline leukemia and heartworm tests.

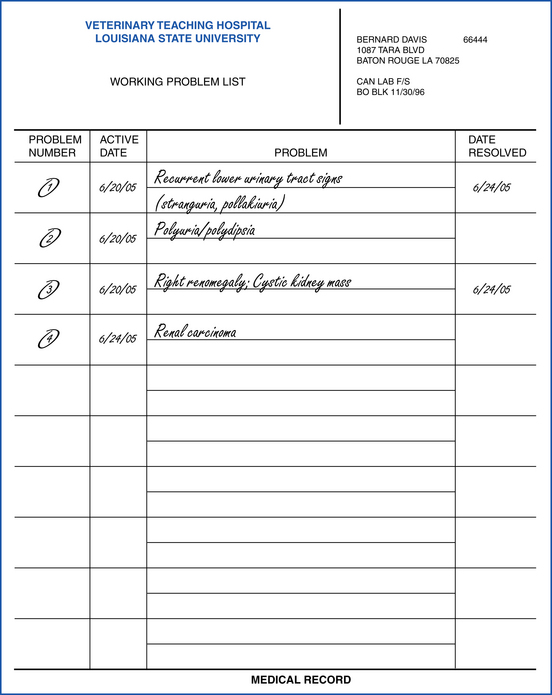

WORKING PROBLEM LIST

The working problem list (Figure 5-9 and Table 5-1) is often used in veterinary teaching hospitals and assists the clinician and student in working through problems that are relevant to the current hospital stay. For example, if the patient is hospitalized and is subsequently diagnosed with autoimmune hemolytic anemia, the working problem list may list symptomatic problems initially until the final diagnosis is made.

TABLE 5-1

| Problem Number | Active Date | Problem |

| 1 | 6/20/05 | Depression/lethargy |

| 2 | 6/20/05 | Pale yellow mucous membrane |

| 3 | 6/20/05 | Mild tachycardia |

| 4 | 6/21/05 | Anemia |

| 5 | 6/21/05 | Icterus |

| 6 | 6/22/05 | Autoimmune hemolytic anemia |

Compare the working problem list with the master problem list. Notice that the master problem list is essentially a list of final diagnoses rather than a list of symptoms. The working problem list helps the clinician to list clinical signs as they become apparent without offering a specific diagnosis. When a final diagnosis is reached, such as autoimmune hemolytic anemia in this case, the diagnosis can be added to the master problem list.

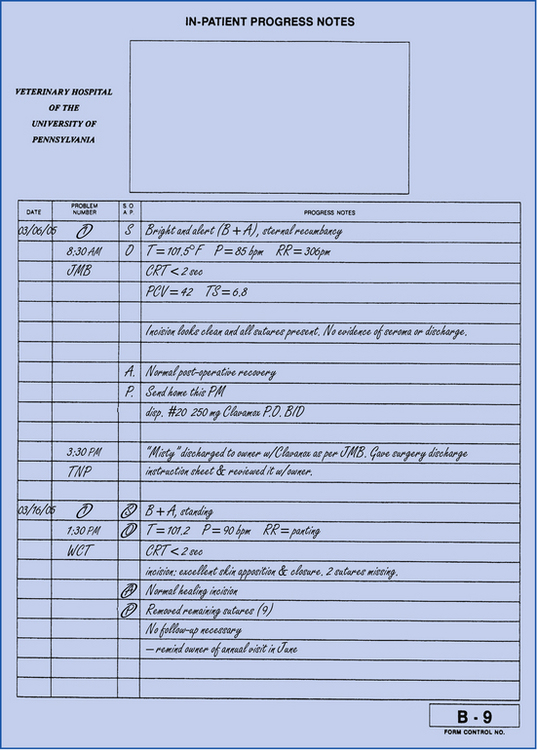

PROGRESS NOTES

The ongoing management of veterinary patients is documented in the progress notes (Figure 5-10). Each time a patient visits the veterinary hospital, notes are made to summarize the visit. The date of the appointment, physical examination findings, and the reason for the visit are noted. If the animal is sick, problems are listed and a tentative diagnoses or list of differential diagnoses is generated. If diagnostic procedures are performed, the findings are entered and a definitive diagnosis may be noted together with therapeutic plans, the medication given, and the patient’s prognosis. Communications with the client and any changes in therapy are also noted.

When the patient is hospitalized, progress notes are used to record the daily events. In many practices and in teaching hospitals, the patient is examined carefully at the beginning of each day. Therapeutic treatment and plans are evaluated and adjusted according to the progress of the patient. This process is called a morning SOAP. SOAP is an acronym for subjective, objective, assessment, and plan. In teaching hospitals, the SOAPs are typically performed by the veterinary medical students and residents. In private practices, veterinary technicians often complete the first half (S and O) of the SOAP, whereas the latter half (A and P) may be completed by the veterinarian. The subjective portion of the SOAP refers to the way the patient appears from the point of view of the casual observer. The patient, for example, may be “standing, panting, and wagging its tail,” or the patient may be “awake, but in left lateral recumbency.” Vocalizations, body posture, attitude, and positions are all noted as “subjective.”

The objective portion of the SOAP includes physiologic data, such as temperature, pulse, and respiration. The examiner would also note any vomitus, urination, and defecation and would describe the color and consistency of these, if applicable. If the patient were on intravenous fluid therapy, a small sample of blood would be drawn and the packed-cell volume, total solids, and results from the azodipsticks and dextrodipsticks would be recorded. Other easily accessible data, such as sodium and potassium values, might also be noted here. If the patient had surgery, notes regarding the surgical site, number of sutures present, and the level of swelling or drainage would also be made. If a urinary catheter and collection bag had been placed, urine output would be recorded.

Under the section assessment, the examiner would record the status of the patient. If the patient had undergone surgery, for example, the note might read “nonremarkable recovery postoperative” or “localized inflammatory response to suture material.” An assessment for a medical case might read “polyuria and polydipsia noted with hyperglycemia. Diabetes mellitus likely.”

Plan refers to the course of action that will be taken that day. Perhaps the patient will be discharged and given take-home medication, or perhaps the patient will undergo more diagnostic testing and observation. The medication to be given, procedures, and treatment plans to be performed are all described in this portion of the SOAP.

In teaching hospitals, an assessment and plan are sometimes written for each of the problems in the working problem list separately. Because this approach can lead to a lot of paperwork, an alternate method is to write an assessment and plan for the patient as a whole. Often the conditions and special circumstances of the case determine which approach is taken.

Any incoming information from a referring veterinarian or an animal’s owner would also be placed in the progress notes section in chronologic order. Communication with the owner either in person, by telephone, or by e-mail is recorded in the progress notes in chronologic order.

WARD TREATMENT SHEETS AND CAGE CARDS

Carrying out the treatments of hospitalized patients can be complicated, particularly in busy practices with heavy caseloads and in practices that treat emergency and critical care patients. To assist the veterinary health care team in carrying out the prescribed treatments efficiently, a treatment grid may be used. The grid may be part of a letter-size, ward treatment form that is kept in the patient’s file (see the Evolve site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/McCurnin/vettech/), or it may be stamped on a card that is placed on the cage of the patient. The grid lists the treatments to be given and specifies the times throughout the day when each of the treatments should be completed. Specific doses, methods of administration, and cautionary notes should be noted. Examples of specialized ward treatment sheets for equine patients with colic (A) and diarrhea (B) and foals housed in the intensive care unit (C) can be found on the Evolve site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/McCurnin/vettech/. In most practices, the medications and supplies needed to complete the treatments are kept near the patient for convenience. Some practices store a patient’s medications and treatment supplies in bins on a table or shelf along with the patient’s medical record (Figure 5-11, A). Other practices prefer to use baskets that can be suspended from the patient’s cage together with the ward treatment sheet (Figure 5-11, B). Hospitals for equine and food animal patients often maintain medications and supplies in treatment carts that can be wheeled easily in the barn aisles from stall to stall. Regardless of the approach used, it is important to label the medications and supplies clearly with the patient’s name, signalment, and owner information.

FIGURE 5-11 A, Some practices use individual bins to store the medications and supplies of each patient. These are kept near the medical record and are labeled with the patient’s name. Notice that records kept on the wards are stored in protective metal holders. The record is removed from the holder before it is filed. B, Some practices store patient medications in wire baskets that can be attached directly to the door of the patient’s cage. Medical records can also be attached to the cage. Both the record and the medications must be labeled clearly.

Cage and stall cards are used to identify the patient and the reason for the hospitalization. The owner’s and patient’s information is stamped on the card. In some practices that do not use separate ward treatment sheets, the treatment grid is also stamped on the cage and stall card and lists the procedures to be performed. In some specialty practices, the color of the card may be used to indicate the hospital division that is treating the patient. A red card, for example, might indicate surgery, whereas a blue card might indicate internal medicine or cardiology.

PERTINENT FORMS

Depending upon the size and caseload of the veterinary practice, there may be separate forms for different hospital departments, specialists, or diagnostic procedures. Anesthesia, surgery, recovery, and pain management forms, for example, may all be pertinent to a patient that has undergone a surgical procedure (see the Evolve site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/McCurnin/vettech/). Similarly the results of diagnostic procedures, such as radiography and endoscopy, and laboratory tests may all be found in the medical record of an animal that had an esophageal foreign body (see the Evolve site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/McCurnin/vettech/).

LABORATORY DIAGNOSTIC SUMMARY AND FLOW SHEET

The laboratory diagnostic flow sheet is a compilation of laboratory data collected from an individual animal. It can be used for outpatients or inpatients. It shows at a glance the different laboratory values for the tests that have been performed on the patient. Specific values can be compared on the different dates for blood counts, chemistry panels, blood gases, urinalyses, and coagulation rates (see the Evolve site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/McCurnin/vettech/). This sheet is of particular value when evaluating internal medicine cases, such as animals with diabetes, anemia, chronic renal failure, hepatic failure, Addison’s disease, and Cushing’s disease. Two spaces at the bottom of the left column are reserved for additional laboratory data that is not already listed in the grid.

CONSULTANTS

Teaching and referral hospitals are often divided into departments. Specialties such as behavior, dermatology, medicine, neurology, nutrition, oncology, ophthalmology, orthopedics, and surgery are examples of the departments that can make up a large teaching and referral center. As cases are worked up, specialists may be consulted to address specific problems that the patient is experiencing. A consultation form would be employed, and the consulting veterinarian’s findings, diagnosis, and recommendations would be recorded. Refer to the Evolve site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/McCurnin/vettech/. A copy of the consultation form is kept in the patient’s record.

CASE SUMMARY AND DISCHARGE INSTRUCTIONS

When the patient is ready to be discharged, a summary of the case is written and discharge instructions are prescribed by the clinician. In some practices, the summary and home instructions are included on the same form. A copy of the form is given to the owner, and the veterinarian or veterinary technician reviews it with the owner before the animal leaves the hospital. In this way, the owner has a written account of the pet’s diagnosis and treatment, which can be referred to frequently. The discharge instructions are written out clearly and reviewed directly with the owner (see the Evolve site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/McCurnin/vettech/). Often the clinician’s name and contact information are included on the form so that the owner can call if questions or problems arise. If the animal was hospitalized at a specialty and referral center, the veterinarian often writes a formal letter to the referring veterinarian summarizing the case. In some veterinary practices, a copy of the case summary and discharge instructions form is mailed to the referring veterinarian in lieu of a formal letter.

Several days after a patient is discharged, the veterinarian often completes a follow-up call to the owner. This enables the clinician to assess the patient’s progress at home and gives the owner an opportunity to ask questions. Pet owners are often grateful and appreciative of the special care that a follow-up call represents.

CONSENT AND AUTHORIZATION FORMS

Consent and authorization forms document in writing an understanding between the veterinary practice and the pet owner. The forms outline the specific conditions, risks of the procedure, and responsibilities of the two parties. In keeping with the doctrine of informed consent, completed authorization forms provide veterinary practices with legal evidence that the owner was informed of important information and that the owner agreed to pursue a particular course of action based on the circumstances and information given to him or her.

In many practices, consent forms are generated in those areas where there is the greatest potential for bad feelings as a result of poor communication. Obtaining authorizations to perform surgery, necropsy, and euthanasia are a few examples of situations where written owner permission and verbal communication are critical. During emergencies, for example, owners can be particularly emotional and may have difficulty making clear decisions. Owners who decide to euthanize their seriously injured pet may regret their decision later. They may blame the veterinary staff for feeling “pressured into it” or believe that they were not given all of the necessary information needed to make a sound choice. Authorization forms, such as the one posted on the Evolve site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/McCurnin/vettech/, verify the identity of the owner and free the practice of liability in performing euthanasia. Signed consent forms are part of the medical record and should be stored and filed with the medical records.

A common source of consternation in veterinary practices is miscommunication regarding the cost of services. Many veterinary hospitals have developed fee-estimation and consent-for-treatment forms (see the Evolve site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/McCurnin/vettech/). These forms give owners a written estimate of the cost of the procedures, verify ownership, and establish an agreement in the event that the animal is abandoned by the owner. This empowers the practice to take action in the event that the owner cannot meet his responsibility to pay for services and/or retrieve their pet.

Obtaining consent from the owner is recommended whenever there is an indication that a client might end up causing a problem. Often legal difficulties can be prevented by identifying potentially difficult clients in advance. Having the owner’s written consent to restrain his or her own pet during an examination, for example, may protect the practice later if the client is bitten. Sometimes an owner that normally insists on holding their own pet during an office visit may decide not to after reading and signing a consent form that lists the risks of restraining an animal.

LOGS

In addition to the documents contained within the patient record, medical information is maintained continuously in logs that are located throughout the veterinary hospital. In many practices, there are logs for radiology and special imaging, surgery, anesthesia, controlled substances, ultrasound, clinical laboratory, and euthanasia. In addition, some practices have unexpected death, drug reaction, and medical waste logs. Any division of the veterinary hospital or specific activity could conceivably have a log that records the daily activity in that particular aspect of the hospital. Some large practices may have 8 to 12 different types of logs, whereas smaller practices may have two to four logs.

1. They provide additional documentation for legal support.

2. They provide data for quick analysis and retrospective studies.

A practice that is interested in examining the average length of surgery, for example, can quickly calculate that figure based on data in the surgery log. In radiology, techniques could be evaluated by examining the recorded settings in the x-ray log. Typically, logs are kept in binders or bound composition books so that pages cannot be lost or discarded accidentally.

Some of the commonly used logs are listed below.

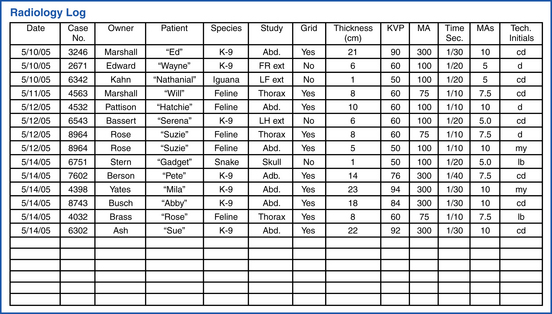

RADIOLOGY LOG

The radiology log records the technique used for every x-ray taken. It includes the following:

• Patient’s name and identification (ID) number

• Measurement of body thickness

• Technique used: milliamperes (mA), time, kilovolts peak (kVp)

The radiology log is typically completed by the veterinary technician (Figure 5-12) and is particularly helpful when improved exposure technique is desired and repeat films are requested.

SURGERY LOG

Although there is much variation from practice to practice regarding the content and structure of the surgery log, most contain the following information:

The surgery and anesthesia logs are particularly helpful when completing retrospective studies regarding the cost of performing each surgical procedure and regarding surgical complications (see the Evolve site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/McCurnin/vettech/). Some practices have separate surgery and anesthesia logs, whereas other practices combine the information to prevent redundancy.

ANESTHESIA LOG

The anesthesia log documents the anesthetic protocol used in surgical and nonsurgical procedures. Dental procedures, thorough ear examinations, and bone marrow aspirates are all examples of procedures that would require anesthesia but that might not be entered into the surgery log. Information contained in the anesthesia log might include the following:

• Relative risk category or result of physical examination

• Anesthetic protocol, including type and dosage of each anesthetic agent

• Anesthesia start and end time

• Number of intubation attempts

The anesthesia log complements the information entered on the anesthesia form (see the Evolve site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/McCurnin/vettech/). Some of the information is repeated and is found in both the log and the form. However, the advantage of the log is that it is easily accessible (the notebook often sits out) and represents a summary of all of the anesthesia cases. The anesthesia form, on the other hand, although it contains more detailed information, is not as accessible and contains information about one anesthesia case.

NECROPSY LOG

The necropsy log is a compilation of data regarding the death of animals. It includes the date and cause of death and type of necropsy performed (see the Evolve site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/McCurnin/vettech/). It also contains the owner’s name, case number, species, name of the veterinarian performing the evaluation, histopathology and gross findings, and special tissue submitted. The log is typically kept in the necropsy area.

CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES LOG

The Comprehensive Drug Abuse and Control Act (the act) is federal law that was passed by Congress in 1970 and regulates the possession of drugs that have the potential to be abused. These drugs are called controlled substances. In the act, the drugs are categorized according to their potential for addiction. The categories range from Schedule I drugs, which are the most addictive, to Schedule V drugs, which are the least addictive. Schedule I drugs include LSD, heroin, crack cocaine, and peyote and have no accepted medical use. All of the other scheduled drugs (Schedules II, III, IV, and V) must be securely stored in a locked cabinet and inventoried separately from noncontrolled drugs. An inventory of all controlled substances must be made every 2 years, though most practices do this annually. The inventory should include the following:

A separate inventory record must be kept for each Schedule II drug. The records for Schedule III, IV, and V drugs may be combined into one log, but must be kept separate from the other practice records. In addition, all drug-log information must be kept in a bound composition book or book in which the pages cannot be torn out without notice. Although specific requirements vary from state to state, a typical controlled substances log includes the following:

ORGANIZATION AND FILING

Many veterinary hospitals use a folder system that is developed specifically for veterinary medicine. There are a number of companies that make a variety of systems, so they are easy to acquire (you can order them from a catalog), and there is a wide selection of styles, sizes, and colors (see Figure 5-1). Most folders include internal flexible clips that hold forms in their correct order (Figure 5-13). In addition, the folders are designed to accommodate color-coded tabs or stickers (known as signaling devices) that are applied to the outer edge of the folder making filing more efficient and filing errors easier to identify.

FIGURE 5-13 Letter-size folders contain flexible metal clips that hold forms in their correct order. Dividers allow for rapid retrieval of lab reports, operative notes, and progress notes.

ALPHABETIC

Colored stickers are sold separately, which allows the practice to choose the organizational scheme of the color-coding system. For example, it can be alphabetic, numeric, or a combination of both. In the alphabetic system, a different color is given to each letter of the alphabet. It is easy to learn and does not require cross-referencing with a master list of clients. The primary challenge of using the alphabetic system, however, is that the employee doing the filing must be careful to correctly apply the alphabetic order and spell the clients’ names without exception. Unfortunately, errors in spelling and filing do occur from time to time, so misfiled records tend to be more common with the alphabetic system than with other systems.

NUMERIC

In the numeric system, each client is assigned a number. The number assigned to the file may be a hospital-generated number or the client’s telephone or social security number. Each digit in the number has a different color, and the files are shelved from lowest to highest (Figure 5-14). In this way, it is easy to correctly sequence the files, and any misfiled records are easily identified because the file color sequence does not match those of the surrounding files. Can you see the misfiled record in Figure 5-15? To retrieve a particular file, the receptionist must first check a cross-reference that lists the client’s name and the corresponding file number.

One of the advantages of the numeric filing system is that fewer filing errors occur because numbers are easier to read and interpret than letters, and spelling is not a factor. In addition, numeric filing systems are practical for large-volume practices because no file duplication occurs, whereas in the alphabetic system, there may be many clients named Jones or Brown. The disadvantage of the numeric system, however, is that a cross-reference list must be generated and maintained. If telephone numbers are used, the files will have to be assigned a new number and refiled whenever a client moves or changes telephone numbers.

Additional colored tabs can be applied to files to alert the receptionist of specific client-patient issues. For example, the records of animals that need immunizations and worming can be flagged to indicate that reminders should be mailed out. Colored flags may also indicate those clients that have an outstanding bill or that have not returned to the practice in a long time. In this way, colored signaling devices can be added to identify groups of files that need attention.

FILE PURGING

Periodically the collection of medical records should be reviewed and purged of files that are not in current use. Each veterinary hospital has its own review and purging schedule; however, the following rules can be a helpful starting point:

1. The collection of medical records should be reviewed at least once per year.

2. Active records covering a 3-year period are maintained in the primary medical records collection.

3. Records that have been inactive for 4 years or more are moved to storage. Storage should be easily accessible.

4. Records 8 years old or older may be removed from storage and shredded.

Use of color-coded tabs with the year can be of particular value when completing the annual review of medical records. They enable the receptionist to quickly identify the 4-year-old and 8-year-old records by their specific colors.

LOST RECORDS

The risk of losing records in both a small and a large hospital is problematic. They can be lost through misfiling, incorrect spelling of names, or misplacement. At times even after an exhaustive search, the record continues to be missing. Sometimes the loss is not discovered until the animal comes back to the practice for a return visit.

It is best, in this case, to explain to the client that the record has been misplaced. A new record should be started and information requested from the client and veterinarian. In addition, copies of laboratory data, pathology reports, and radiologic information should be obtained and added to reestablish the file.

Although the problem of lost records is embarrassing to the practice and inconvenient to the client, it will happen with even the most elaborate record keeping system; however, every effort possible should be made to quickly and accurately file each record after each visit. Clients feel more at ease and welcomed if the record is complete and easily accessible.

ETHICAL AND LEGAL ISSUES

The laws concerning ownership of medical records vary from state to state. However, in general, the records made during the course of a patient’s treatment are owned by the veterinary hospital or hospital owner. Although the client purchased the veterinary services that generated the medical information, the client is not, by law, the owner of the medical record. However, the owner may request a copy of the record at any time. It is customary for clients to request copies of their pet’s medical record when they are moving and changing veterinary practices. This facilitates continued care of the patient and prevents repetition of immunizations or diagnostic tests. It is recommended that copies of medical records be mailed to the successive veterinarian and not hand delivered by the owner who may be apt to misinterpret the status of his or her animal’s health. A cover letter should be included with the copy of the record so that the original veterinary hospital and veterinarian can be easily contacted, if necessary. A flat fee for copying the record may be charged, or the practice may levy a fee on a per-page basis.

RELEASE OF MEDICAL INFORMATION

A signed authorization form (see the Evolve site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/McCurnin/vettech/) or a written letter of request for record copies should be obtained from the animal’s owner before any information is released to him or her, another veterinarian, or an insurance company. The practice owner should be the only person to authorize the release of information contained in the record. However, there is an exception to this rule. Local, state, and federal agencies require the reporting of certain diseases that may be dangerous to the public or to the widespread health of animals. These are called reportable diseases and include rabies, brucellosis, and equine encephalitis. Additional regulations regarding reportable diseases can be found in the Animal Movement Quarantine Regulations Manual that is published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). In addition, physicians, animal control agencies, and the regional department of health may inquire about the rabies immunization status of an animal that has bitten a human.

MEDICAL AND LEGAL REQUIREMENTS

It is important to keep in mind that the medical record is a legal document and could be used in a court of law. It is generated not only to ensure consistent and accurate veterinary care, but also to protect the veterinarian against potential malpractice litigation. Any written data contained in the medical record must be complete, accurate, and legible. An inaccurate, illegible, or incomplete record may be construed as evidence of professional incompetence and substandard care. Keep in mind that in a court of law, “if it was not written down, it didn’t happen,” and “if the writing is illegible, it was not written down.” Below are some guidelines for generating clear, complete, and accurate records.

1. Entries should either be typed or written in black ink.

2. In a court of law, handwriting alone is not an adequate way to identify the author of a notation. Entries should be dated and initialed to identify the person making the entry. Additional validity to an entry can be made by entering the time and the date.

3. Errors should not be scratched out, erased, or blotted out. Instead, a single line should be drawn through the mistake and initialed. The correct information should then be written in the margin and initialed and dated next to the correction. Any erasure or blotting out may suggest tampering of the record and could render the document inadmissible in a court of law.

The medical record is considered legal evidence of services and procedures performed by the veterinary health care team. In the event of litigation, such as during a malpractice or insurance suit, the record could be subpoenaed and admitted as evidence.

Legal guidelines for medical records vary from state to state and may dictate the type of information that should be included, how long the record should be kept, and restrictions on the release of medical information. It is recommended that all members of the veterinary health care team be familiar with the laws of the state in which they work.

VETERINARY MEDICAL DATABASE

The Veterinary Medical Database (VMDB) is a national data bank located at Purdue University. It contains computerized veterinary medical data supplied by 24 veterinary schools in the United States and Canada. Each institution submits data for the VMDB on a quarterly basis to a central processing center. The data consist of abstracted data from each clinical case seen at each teaching hospital. The national database allows studies of national trends in various animal diseases. It provides patient chart number, institution code, date of visit, length of stay, clinician code, gender, species, breed, discharge status, age, weight, diagnosis, and procedures for each animal. The VMDB is available for use in retrospective studies and in the evaluation of national and regional disease patterns.

COMPUTERS

Computers have become an integral part of veterinary practice management today. Software packages designed specifically for veterinary practices help organize a wide range of management issues, such as billing, reminders, scheduling, and inventory in addition to medical records. Chapter 4 addresses these and other topics regarding the use of computers in veterinary practice.

RELATED ASSOCIATIONS

American Animal Hospital Association, 12575 West Bayaud Ave., Lakewood, CO 80228

American Health Information Management Association, North Michigan Avenue, Suite 2150, Chicago, IL 60601-5800, www.ahima.org

American Veterinary Health Information Management Association, c/o Flo Nelson, University of Missouri, Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, 379 E. Campus Drive, Columbia, MO 65211

American Veterinary Medical Association, 1931 N. Meacham Road, Suite 100, Schaumburg, IL 60173-4360

AAHA. Standards of accreditation CD-ROM. Lakewood, Colo: American Animal Hospital Association, 2003.

Allen, D.G. The problem-oriented approach. In: Small animal medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1991.

Heinke, M.L., McCarthy, J.B. Practice made perfect: a guide to veterinary practice management. Lakewood, Colo: American Animal Hospital Association, 2001.

Johns, M.L. Information management for health professions, ed 2. Delmar, 2002.

Johns ML: Health information management technology: an applied approach, American Health Information Management Association.

Peden AH: Veterinary settings. In Comparative records for health information management, Delmar.

For access to all of the medical record forms discussed in this chapter, see the Evolve site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/McCurnin/vettech/.

TECHNICIAN NOTE

TECHNICIAN NOTE

oval mass palpable approx. 2 cm × 2.5 cm.

oval mass palpable approx. 2 cm × 2.5 cm.