Occupational Health and Safety in Veterinary Hospitals

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

1 Describe the role of OSHA in veterinary practice safety.

2 List the general requirements of the federal laws related to workplace safety.

3 Explain proper methods for lifting objects and animals.

4 List common workplace hazards in a veterinary facility.

5 Describe the requirements and the OSHA “right to know” law.

6 Explain the acronym MSDS and describe the components of an MSDS.

7 List the hazards associated with the use of ethylene oxide, formalin, glutaraldehyde, anesthetic gases, and compressed gases.

8 Define the term zoonotic disease and list common zoonotic diseases encountered in the veterinary practice.

9 List methods to minimize the hazards associated with animal handling.

10 Describe the proper handling of hazardous and medical wastes.

SAFETY

OBJECTIVES OF A SAFETY PROGRAM

The purpose of any safety program is to reduce or eliminate the possibility of injuries or illnesses to employees. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) enforces federal laws that help to ensure a safe workplace for American workers. These laws require employers to have a safety program, which includes educating employees about the inherent risks in their jobs, providing them with appropriate safety equipment, and training them in safety procedures and the proper use of safety equipment. If you are receiving this training from your employer, she or he is fulfilling important OSHA requirements. If you are learning this material as a self-study program, you can take pride in the knowledge that you are becoming a “self-taught expert” in the field of occupational safety. Your knowledge and initiative will be a welcomed component to your veterinary health care team.

YOUR SAFETY RIGHTS

One can never eliminate every hazard completely, but each of us can minimize our exposure to them in most cases.

The ability to participate in a safety program at work is an important part of your rights. It is often assumed that the owner and/or manager of a business knows all that there is to know about the business. But too often it is the employee who first becomes aware of potential safety problems. As an employee, you have the right to bring those concerns to the attention of the employer without fear of reprisal. In most instances, the complaint is first presented to the immediate supervisor, but be aware that not all complaints will bring about changes to the operation of the practice. Some complaints stem from a lack of familiarity with standard safety procedures on the part of the employee, and in these cases, instruction by the employer is all that is needed to resolve the issue. However, if a complaint is not taken seriously by the employer or if there is a dangerous situation that is not adequately addressed, the employee has the right to bring the issue to the attention of the regional OSHA office.

When records, such as medical evaluations or radiation exposure reports, are collected by the veterinary hospital, the records must be made available to the employee for review. This does not mean that you are entitled to see private or sensitive information about other staff members, but it does mean that you are entitled to see data that is relevant to your safety. You are also entitled to know about the nature and type of accidents that have occurred in your hospital. If your practice employs more than 10 employees, you have the right to view the summary of work-related injuries and illnesses (OSHA form 300A), which should be posted on the employee bulletin board at certain times of the year.

YOUR SAFETY RESPONSIBILITIES

It is your responsibility to learn and follow the safety rules and practices that have been established for your position in the veterinary hospital. Even though OSHA will not cite or fine the employee directly for violations of these responsibilities, he or she is required under the Occupational Safety and Health Act (the act) to “comply with all occupational safety and health standards and all rules, regulations, and orders issued under the Act.” This not only includes specific OSHA standards, but it also applies to workplace-specific rules established by the leadership in your hospital.

Although you cannot be disciplined by your employer for exercising your rights under the act, you can be disciplined by your employer for willful violations of any safety rule or standard. In some cases, this discipline can be as simple as a verbal reprimand, but in severe or chronic situations, it can include termination. In most states, if you are terminated for the willful violation of safety rules, you will likely be denied unemployment benefits.

In addition to the responsibility to follow the rules, the act requires you to:

• Read the OSHA poster (Figure 6-1).

• Comply with all applicable standards.

• Wear or use prescribed personal protective equipment (PPE) while working.

• Report hazardous conditions to your supervisor.

• Report any job-related injury or illness to the proper person and seek treatment promptly.

THE LEADERSHIP’S RIGHTS

Although the act and OSHA require the leadership of a business to maintain safety standards, this is not meant to restrict their right to set rules of conduct or operation for its staff. The practice owner, for example, has the right to set and enforce rules for his or her own practice as long as those rules are consistent with federal safety laws.

Practice owners must have ample time to correct any safety-related problems. In other words, the employee should not rush off to file a grievance with the regional OSHA office without first giving the employer ample time to correct the deficiency.

In the event that a practice is inspected, the practice owner has the right to be present because the practice is considered his or her personal property. An employee is not authorized to admit an OSHA inspector to the practice in the absence of the employer (unless, of course, the employer specifically gives the employee the authority to act on his or her behalf). However, OSHA inspectors may enter a practice without the presence of the owner and without permission by the employee if the inspectors have a court order to do so.

THE LEADERSHIP’S RESPONSIBILITIES

The leadership of a veterinary practice is responsible for providing a safe work environment for the employees. This does not mean providing a facility with no hazards—that would be impossible. It means that the leadership must make a reasonable effort to identify the hazards present, correct the ones that can be eliminated, and control the ones that cannot be eliminated.

The practice must comply with the laws and regulations pertaining to safety and health by establishing safety procedures for the hospital, including emergency procedures for addressing employee’s accidents. The leadership must enforce these rules as diligently as it would be expected to enforce any other rule in the practice.

The employer is also responsible for providing practice-specific safety training to the employees (Figure 6-2). Even if a veterinary technician has years of prior experience, the practice is required to make sure that the technician is capable of doing her or his job safely. This training can be provided in a formal setting, such as in staff meetings or a continuing education course, or it can be given in the practice. A great deal of learning takes place in many practices every day. On-the-job training can be an effective way to obtain knowledge about safety, but be sure you know your limits and abilities. Ultimately, you are the best person to determine if you are competent to do a job safely. If you think you need extra safety training in an area, do not hesitate to ask for it. Tell your supervisor immediately so that arrangements can be made for the proper instruction.

GENERAL WORKPLACE HAZARDS

Every practice should have a collection of written safety-related policies known as the Hospital Safety Manual. You should know where the Hospital Safety Manual is located in your practice and take time to become familiar with it. Memorize the “do’s and don’ts” for your particular veterinary hospital and always follow the safety rules. No one can protect you from an injury or illness better than you.

DRESSING APPROPRIATELY FOR THE JOB

One of the first rules of safety is to dress appropriately for the job at hand. In the veterinary profession, this includes protective footwear and minimal, if any, jewelry. You can reduce the chances of getting injured by wearing shoes that cover your whole foot (not sandals or open-toed shoes) and that have nonslip soles. Be especially cautious walking on uneven or wet floors. Never run inside the hospital or on uneven footing. Excessive jewelry can present a hazard in many clinical situations, but particularly when an animal struggles during restraint and can inadvertently link an earring or necklace with a claw. This is definitely one of those circumstances when less is more.

SAVE YOUR BACK!

According to insurance statistics, back injuries account for one in every five workplace injuries among American workers. To minimize your chances of suffering one of these painful injuries, remember the rules for lifting: keep your back straight and lift with your legs (Figure 6-3). Never bend over at the waist to lift an object. That rule applies when lifting patients and inanimate objects, such as boxes or supplies. If your practice does not have a motorized lift table, get help when lifting patients more than 40 lb. Remember to follow sound ergonomic principles when positioning or restraining patients, especially when working with horses or food animals.

Because veterinary technicians perform such a variety of jobs in any given hour, it is rare for us to acquire the types of ergonomic injuries common in other industries (such as carpal tunnel syndrome). However, it is important to note that the best defense against almost all ergonomic injuries is to change your posture and routine frequently.

CLEAN UP AFTER YOURSELF

Some injuries are caused by cluttered or dirty work areas. In addition, clutter is known to contribute to the severity of accidents that otherwise would be minor. Cleanliness and organization are good business standards, especially in a health care facility. Always clean up spills as soon as they happen. You should always clean and return equipment to the proper storage place immediately after use. At least daily, remove all trash from your work area. Organize drawers, cabinets, and counters so that items can be found easily and clutter is reduced.

EVERYTHING IN ITS PLACE

Supplies and equipment should always be stored properly. Heavy supplies or equipment, for example, should be kept on the lower shelves to prevent unnecessary strain in trying to lift them overhead and to reduce the risk of material falling on your head. Never use stairways or exit hallways as storage areas. Do not overload shelves or cabinets (Figure 6-4). Store liquids in containers with tight-fitting lids and always replace the lids when finished using the product. Whenever possible, store chemicals on shelves at or below eye level; this will minimize the possibility of accidentally spilling the chemical on you when getting or replacing a container. Never climb into or on cabinets, shelves, chairs, buckets, or similar items. Use an appropriate ladder or step to reach high locations.

BEWARE OF BREAK TIMES

The ingestion of pathogenic organisms or harmful chemicals while eating on the job is a possibility in veterinary hospitals. This is why it is important to eat and drink only in areas designated for staff breaks that are free of toxic and biologically harmful substances. This also applies to the preparation of food and beverages. Make sure coffeepots and utensils are well away from the sources that could contaminate food, such as laboratories and treatment and bathing areas. Check the cabinets or shelves above food preparation areas to ensure that no hazards could spill onto the area. Always store food, drinks, condiments, and snacks in a separate refrigerator from the one used to store biologic or chemical hazards, such as vaccines, drugs, and laboratory samples.

MACHINERY AND EQUIPMENT

Never operate machinery or equipment without all the proper guards in place. Equipment such as fans and cage dryers have moving parts that can severely hurt or even sever a finger. Long hair should be tied back or pinned up to prevent it from getting caught in fans or other moving parts. Avoid wearing excessively loose clothing or jewelry when working around machinery with moving parts.

When using equipment such as autoclaves, microwave ovens, cautery irons, or other heating devices, be sure to understand the proper rules for safe operation. Burns, especially from steam, are painful and serious and almost always can be prevented. Autoclaves also present a danger from the pressure that is used for proper sterilization. Before opening an autoclave, be sure to first release the pressure by activating the vent device, and at the same time keep your hands and face away from the steam. Let the steam dissipate completely before opening the door fully and be careful when removing the packs because they may still be hot. Always assume cautery devices and branding irons are hot, and use the insulated handle whenever you touch them. Never place heated irons on any surface where they could overheat and start a fire or where someone might accidentally touch them.

ELECTRICAL

Many procedures performed on a daily basis require the use of electricity. Although new equipment and buildings have many safety features built into the design, you must be conscious of preventing a situation that could cause a fire or physical harm to yourself, another person, or a patient.

Do not remove light switch or electrical outlet covers. Always keep circuit-breaker boxes closed and never block access by stacking supplies or equipment in front of them. Only persons trained to perform maintenance duties should repair electrical appliances, outlets, switches, fixtures, or breakers.

If you must use a portable dryer or other electrical equipment in a wet area, make sure it is properly grounded and only plugged into a ground-fault circuit interruption (GFCI) type of outlet. Extension cords should only be used for temporary applications and should always be of the three-conductor, grounded type. Never run extension cords through windows or doors that may close and damage the wires or across aisles or floors where a tripping hazard may be created.

Surge suppressors should only be used to protect sensitive electronic equipment and should never be overloaded (Figure 6-5). In addition, surge suppressors should never be used with portable heaters, autoclaves, or coffeepots because they may overheat and cause a fire.

Equipment with grounded plugs must never be used with adapters or nongrounded extension cords. Never alter or remove the ground terminals on plugs. Appliances or equipment with defective ground terminals or plugs should not be used until repaired.

When changing light bulbs (especially fluorescent bulbs), be careful to remove and replace the bulb without breaking it. Inoperable bulbs should be disposed of directly into the outside dumpster or inside of a container to keep the bulb from breaking.

FIRE AND EVACUATION

The potential for the dramatic loss of life (both human and animal) and the destruction of property make a hospital fire one of the most feared accidents imaginable. Fortunately, this danger can be significantly reduced by a few simple precautions.

Never use power adapters or surge suppressors as a substitute for permanent wiring. Overloaded or faulty electrical cords can overheat or short out and start a fire, even when the equipment is turned off.

Always store flammable liquids properly; many, such as gasoline, paint thinner, and ether, should never be stored inside the hospital except in an approved flammable storage cabinet. Some components of specialty dental and large animal acrylic repair kits are also flammable. Very small amounts of these components are usually not a problem, but always ensure that they are stored and used in an area with good ventilation and that the containers have tight-fitting lids that are replaced immediately after use.

Flammable materials, such as newspapers, boxes, and cleaning chemicals, must always be stored at least 3 feet away from an ignition source, such as a water heater, furnace, or stove. Always use extra care when using portable heaters. Never leave them unattended and always make sure they are placed no closer than 3 feet from any wall, furniture, or other flammable material.

Become familiar with the location of the emergency exits in your facility. Make sure the emergency exits are always unlocked and free from obstructions when you are in the building. If you must work in a building when security warrants that the doors be locked, make sure you have at least two clear exits from the building.

Learn the emergency warning system in your hospital. If the facility is equipped with an electronic alarm system, be sure you know how to activate it manually. In the absence of an electronic alarm system, a verbal alarm is effective. You can use the telephone intercom feature to alert everyone that there is a fire in the building, or in small buildings, simply yell in a loud clear voice to get the message out.

Know your duties in the event of a fire. Remember, your first responsibility is to notify others about the fire and then to get out of the building safely if an evacuation is ordered. Leave the rescue duties to the professionals that are trained and equipped to handle this dangerous task. If you do evacuate the building, immediately report to the designated assembly area for accountability. This is important since others will assume you are trapped in the building if you are not present at the assembly area.

Know where the fire extinguishers are located and how to use them (Box 6-1). Most veterinary hospitals are equipped with dry-chemical type of fire extinguishers. But before you decide to use a fire extinguisher, make sure the alarm has been sounded, everyone has left the building (or is in the process of leaving), and the fire department has been called.

The National Fire Protection Association recommends that you never attempt to fight a fire if any of these conditions are true:

• The fire is spreading beyond the immediate area where it started or involves any part of the building or structure.

• The fire could block your escape route.

• You are unsure of the proper operation of the extinguisher.

• You are in doubt that the extinguisher you are holding is designed for the type of fire at hand or is large enough to suppress the fire.

DO NOT BECOME A VICTIM OF VIOLENCE

Just as in any occupation, you are at risk of injury from accidents not directly related to your job. Vehicle accidents, personal assault, robbery, and even natural disasters have resulted in veterinary technicians being injured while on duty. Although no one can prevent every possible scenario, preparation can certainly help and sometimes will minimize the injury. When outside of the hospital building, be aware of your environment and do your best to avoid placing yourself in a situation that could go bad.

Always keep the “nonclient” doors locked from the outside to prevent anyone from gaining unauthorized or undetected entry into the building (Figure 6-6).

FIGURE 6-6 Personal safety includes the diligent use of locks and barriers to deter unauthorized persons from entering the facility.

If you work in a critical care or 24-hour practice, you should use the “barriers” that are usually available. Things such as buzzers to control access through the front door and one-way locks on the remaining doors (to let you out in case of an emergency, but keep the door locked from the outside) are essential in these environments, so do not prop doors open, disassemble the locking system, or turn the system off. In any business that keeps money or stores valuable items, there is a potential for robbery. If you ever find yourself in a situation where someone demands money, drugs, or other material items while threatening your personal safety—do not withhold the things they demand. As soon as safely possible, let everyone else know of the situation. You should attempt to contact the police if it can be safely done without the person’s knowledge; otherwise, do it immediately after the person has left.

Cooperate with their demands and give them what they want, but do not go with the person. Resist physical assault or battery to the best of your abilities and preferably outside the building so that passersby can see what is happening and render assistance or call the police.

HAZARDOUS CHEMICALS: RIGHT TO KNOW

You may not think about it, but many products that you use every day can be hazardous. Every chemical, even common ones, such as cleaning supplies, have the potential to cause you harm. Some chemicals contribute to health problems, whereas others may be flammable and pose a fire threat. The most common chemicals in use in the veterinary practice are as follows:

Planning and training are the keys to safely handling any chemical. Every business, including your practice, must follow the requirements of OSHA’s “right to know” law. This law requires you to be informed of all chemicals you may be exposed to while doing your job. The right to know law also requires you to wear all safety equipment that is prescribed by the manufacturer and the practice when using any product containing a hazardous chemical. The safety equipment must be provided to you at no cost, but it is not optional—you must wear what is prescribed.

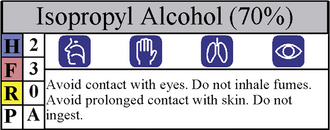

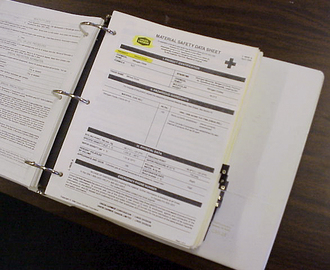

A key component of the right to know law is the hazardous materials plan. The hazardous materials plan includes instructions for organizing and filing the practice “right to know” label, but that information is generally written for the average consumer who will have limited exposure using the product. When a product is used in a business, such as your veterinary practice, you may be exposed to that product more than the average consumer, so your risk may be different. Chemicals, such as alcohol, may be shipped in a large container by the manufacturer and subsequently transferred to smaller containers or spray bottles by hospital personnel to facilitate their use in the practice. It is important to remember to apply a secondary container hazard warning label (Figure 6-7) on the second container to ensure that the chemical is used safely. In addition, the manufacturer of a product that contains a hazardous chemical will prepare a material safety data sheet (MSDS) for that product. The MSDS will give you additional precautions, instructions, and advice for handling that product in the workplace (Figure 6-8). Your practice is required to keep an MSDS library for the chemicals that you use. Ask your supervisor where your hospital’s MSDS library is located. Take the time to review the MSDSs for the products you use frequently. Although MSDSs may look complicated at first glance, the information that is important to you is easy to find: review the health, protective equipment, and disposal sections to gain a better understanding of the risks and precautions you should know.

Working bottles of hazardous products should always have tight-fitting, screw-on lids. Always remember to replace the cap back on the bottle after using any chemical product. You should endeavor to store chemical bottles in a closed cabinet; this will help prevent animals from injury in the event that they escape. Ideally the cabinet or shelf should be at or below eye level. This will minimize the chances of spilling the product in your face if the cap is not secure. Never store or use hazardous products near food, beverages, or food preparation areas.

Be cautious when mixing or diluting any chemical product. Try to keep the material from splashing on your hands, clothes, or face. If it is likely that the product will splash on you, wear a pair of protective latex or nitrile gloves and some protective goggles or glasses. When making solutions from a concentrate, you should always start with the correct quantity of water then add the concentrate. Never add the water to the concentrate because the chemical may splash or react differently.

When two chemicals are mixed together, the result is seldom a simple mixture. It is often a new, sometimes different and possibly dangerous chemical. Never mix any chemicals unless directed to do so on the label or an MSDS.

Minor spills of most chemicals can be cleaned up with paper towels or absorbent (e.g., kitty litter) and disposed of in the trash; however, dangerous chemicals, such as mercury, require special procedures. Before you use a new chemical, review the MSDS and learn the procedures you must follow for cleaning up a spill. When cleaning up any spill, remember to wear protective gloves and any other special equipment required on the MSDS. Keep other people and animals away from the spill until it is safe. Unless prohibited by the instructions on the MSDS, wash the spill site and any contaminated equipment with a detergent soap and water—not a disinfecting soap (Box 6-2).

Familiarize yourself with the locations of the eyewash stations in your practice. Test them regularly and know how to use them before you are in the position to need them.

SPECIAL CHEMICALS

Many hospitals use gas sterilization for items that would be damaged by other procedures. Electrical drills, rubber products, and sharps are commonly exposed to ethylene oxide (EtO) as a sterilization agent in human and veterinary medicine. This method has distinct advantages, but since EtO is thought to be a human carcinogen, special precautions must be maintained.

• Read the MSDS carefully and follow all instructions.

• Store the ampules in a closed cabinet away from sources of heat.

• Only use approved devices for the procedure.

• Read, understand, and follow all the written procedures and safety precautions relevant to your practice.

• Know the emergency procedures to be performed in case of an accidental release of EtO.

Formalin

Historically, formalin has been used in the veterinary profession for tissue preservation, diagnostic tests (knott), and even sterilization. Since formaldehyde is also a suspected human carcinogen, OSHA takes its use seriously. The standards for use of formaldehyde are similar to the standards for use of EtO:

• Read the MSDS carefully and follow all instructions.

• Store supplies safely; include museum jars.

• Use only with good ventilation in the room and avoid breathing vapors.

Whenever possible, you should obtain formalin in small, premeasured containers (also called biopsy jars) so that the serious risk is minimized (Figure 6-9). Often the diagnostic laboratory will supply prefilled biopsy jars at no charge, so be sure to ask.

Glutaraldehyde

Glutaraldehyde is a potent chemical used in the veterinary practice to sterilize hard instruments without the use of an autoclave. Because it is so effective at killing germs, it can also be harmful to other living organisms including you (Figure 6-10). Be sure to follow all the manufacturer’s safe handling rules when using this “cold-sterilization” solution, including washing your hands after handling instruments exposed to the solution and keeping the trays covered to minimize evaporation.

MEDICAL AND ANIMAL-RELATED HAZARDS

We cannot forget that the overriding purpose of a veterinary practice is the care and treatment of animals. But sometimes handling our patients can be a hazard in itself. Anyone who has worked with animals under stress or in pain will relate personal accounts of injuries from patients. Insurance statistics show that animal-related accidents are the most common type of injury among workers in veterinary-related jobs, including veterinary technicians.

Unfortunately, this hazard cannot be eliminated, so we have to do the next best thing—minimize it. The best way to protect yourself from this hazard is to obtain training and practice in animal restraint. The first safety rule when working around animals is to stay alert. Animals sometimes react to situations unexpectedly. Sudden noises, movements, or even light can be the stimulus that would cause an animal to react, so if you are the person responsible for restraining the animal, keep your attention focused on the animal’s reactions and not on the procedure. You must learn the proper restraint positions for each of the species of animals with which you work. Refer to Chapter 7 for additional information about the restraint and handling of animals.

Remember that capture-restraint equipment is available if the animal is fractious or not cooperating; sometimes just a piece of rope to hobble a leg or a piece of gauze for a hasty muzzle will make all the difference. And do not forget that chemical restraint, rather than physical restraint, is often better for both you and the animal, but be sure to ask the veterinarian for approval before administering any medication to a patient.

Large animals, such as horses and cattle, are particularly dangerous and may severely injure or even kill a person when trying to escape restraint. Never put your hand, leg, or any other part of your body between the animal and the side of the enclosure or chute; use a hook or pole to pass ropes or belts through the chute. If you have to enter a stall, paddock, or trailer with a large animal, stay on the side of the animal nearest the door so that you can escape if the situation becomes hazardous. If you must capture a fractious animal from a cage or pen, make sure there is another person present that can assist you if you get into trouble.

If your job entails handling exotic or nondomestic animals, remember that they all have their own unique methods of defense. You should know and understand their possible reactions before you attempt to restrain or treat them.

NOISE

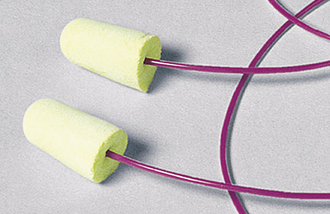

Dogs in cages will inevitably bark, and barking dogs can adversely affect your hearing, especially if you work in an indoor kennel. Noise levels in dog wards can reach as high as 110 dB. Although relatively short-duration exposure to these noise levels, such as going into the kennel just to retrieve a patient, poses no serious damage to your hearing, chronic or long-term exposure can contribute to hearing loss. When working in noisy areas for extended periods of time (e.g., cleaning of cages), you must wear personal hearing protectors (Figure 6-11). It does not matter what style or type of hearing protectors you use (earplugs or muffs), as long as they are rated to filter the noise by at least 20 dB (the package will indicate the rating).

BATHING, DIPPING, AND SPRAYING AREAS

There is probably no area of an animal hospital with a greater risk for injury than in the bathing or insecticide application areas. Although newer parasite control products significantly reduce exposure to pesticides and insecticides, shampoos and medical dips are still a big concern.

The products used for bathing and dipping animals can be harmful to your health and the environment. Even the “all natural” shampoos can cause eye irritation, and you can develop sensitivities to even the mildest products if you are exposed often enough. Because it is impossible to prevent splashing and shaking, it is important to always wear protective glasses or goggles when bathing or dipping animals. In most cases, it is also important to wear gloves and a protective apron to prevent the product from getting on your skin or clothing; this minimizes the amount absorbed through the skin.

Bottles of dips, shampoos, and insecticides should be stored in a cabinet at or below eye level. The bottle should be properly labeled with the contents and any hazard warning that is appropriate (refer to the discussion on chemicals in this chapter for more details). Always replace the cap or lid on the container when you are finished using it to prevent accidental spillage. Plastic containers recycled from other areas can be used for diluted shampoos and dips; however, only use the ones that have a screw-on cap or lid.

Always use a ventilation fan to keep the fumes from shampoos and dips at a safe level. When exhaust fans are too large, they waste heating or air conditioning, so you may be hesitant to use them in some situations. If that is the case, ask your hospital administrator to have a smaller fan installed directly over the tub or area so that fumes can be exhausted without sacrificing the comfort in the room.

Make sure you know where the eyewash station for this area is located. Learn how to properly use the eyewash device before it is needed. If you ever splash a chemical in your eyes, do not rub your eyes with your hands. Immediately call out for help; there is usually someone nearby. With a co-worker’s assistance, go to the eyewash station and flush both eyes (even if only one eye is affected). Avoid using the spray attachments for tubs and sinks since the water pressure is unregulated and the streams of water from these devices can be fine enough to lacerate your cornea.

ZOONOTIC DISEASES

Infectious diseases that can be passed from animals to humans are known as zoonotic diseases. Some zoonotic diseases are not easily transmitted from animals to humans, whereas others are easily spread. You can be exposed to the organisms that cause disease by several means: inhalation, contact with broken skin, ingestion, contact with eyes and mucous membranes, and via accidental inoculation by a needle. There is a wide variety of zoonotic agents to which a veterinary technician may be exposed, certainly more than can be discussed in this chapter. However, some important ones are listed below.

Viral Infections

Rabies is a serious (almost always fatal) viral disease that can affect any warm-blooded animal (including humans). The virus is spread by contact with an infected animal’s saliva. Usually the virus is transmitted through a bite, but it has also been transmitted by open wounds or mucous membranes coming in contact with virus-rich saliva.

Although the disease is ever present in wild animal populations (primarily bats, raccoons, and skunks in the United States), in recent years many states have confirmed record high numbers of rabies in domestic species, such as cats, dogs, horses, and cattle. Several university veterinary hospitals have also recorded cases of rabies in horses, cattle, and companion animals. Some of those animals were even adopted from pet shops. Although rare, it is possible that you will encounter a rabid pet at the veterinary hospital where you work.

It is important that you are aware of the prevalence of rabies and the incidence among wild species in your area because it varies in each region of the country. If you work in a high-risk environment, such as with unvaccinated, stray, and homeless animals in a shelter or with wild animals at a rehabilitation center, you should be immunized with preexposure prophylaxis. Ask your hospital administrator about the availability of these vaccines. They are often available through the occupational health divisions of regional human hospitals. When you must handle an unvaccinated, wild, or stray animal, wear protective (rubber or latex) gloves and wear protective gowns and goggles in cases where the procedure may be “messy.”

Bacterial Infections

There is a wide variety of both pathogenic and nonpathogenic bacteria that you may be exposed to during your professional life. Some examples of pathogenic bacteria include Salmonella spp., Pasteurella spp., E. coli, and Pseudomonas spp. Bacteria can be transferred by direct contact with the animals and their exudates. This is particularly likely if you have any cuts or open sores. Some bacteria may be aerosolized and inhaled or absorbed through mucous membranes. The best protection against exposure to bacteria is simply good personal hygiene. Always follow the personal hygiene rules discussed later in this chapter.

Lyme Disease: Recently, Lyme disease has become a more serious concern for animals and people. When an infected deer tick bites a host (an animal or person) to feed, the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi is transferred to the host. Lyme disease in humans is characterized by aches in the joints, fever, and a host of other flulike symptoms. The best defense against this disease is to check yourself daily for ticks and remove them promptly. If you work in a food- or mixed-animal practice, it is also a good idea to use an insect repellent when you go out into fields or woods to work.

Fungal Infections

Contrary to its name, ringworm is not a parasite or worm. It is an infection of the skin caused by a fungus know as Microsporum sp. Ringworm is passed between animals and humans. Cats and horses are particularly susceptible to ringworm infestations. The most effective protection from ringworm infection is to wear gloves when handling or treating animals diagnosed with the condition and to practice good personal hygiene. Be especially careful about preventing contamination of your clothing when treating patients with Microsporum sp. because it is believed that the fungal spores can be carried to other locations (such as your home) on clothing and infect other animals or other people.

Internal Parasites: When the eggs of common internal parasites, such as roundworms, infect humans, they usually do not mature into adult parasites, but they do cause other problems. Roundworm larvae can migrate to virtually any organ in the body and develop into a cystlike growth known as visceral larval migrans. These “cysts” are usually not clinically noticeable unless they develop in a vital organ such as the eye where they can do permanent damage to the retina and may cause blindness. Puppies almost always have some level of roundworm infestation because the passage of worms from the bitch to the fetus occurs through the placenta and via lactation. When the infected puppy defecates in soil, the roundworm eggs are able to survive for long periods of time until they are picked up and ingested by another mammal.

Another common internal parasite, hookworms, can also cause problems in humans by a condition known as cutaneous larval migrans. This condition is particularly prevalent in southern areas of the United States where there are warm, humid winters. Children who play barefoot where pets defecate frequently may be affected in addition to people who lie on the ground where dogs have defecated. Unlike the visceral cysts from roundworms, the cutaneous larval migrans are relatively easy to spot and appear as small, red lines in the regions where the parasite has burrowed into the skin from the soil. Often these marks are itchy and lengthen as the parasite moves from one part of the body to another, subcutaneously.

External Parasites: The irritating and itchy mite that causes sarcoptic mange can spread easily to humans from animals. Typically, this occurs in regions where there is tight clothing, such as along bra lines and waistbands. When treating animal patients for mange, always wear gloves and a protective gown and wash your hands thoroughly with disinfecting soap immediately after the procedure.

Protozoal Infections

Infestation with a protozoan known as Toxoplasma gondii is called toxoplasmosis. Although it is usually not harmful to most adults, it can have devastating effects on the development of a human fetus by causing hydrocephalus and mental retardation. Nonsporulated Toxoplasma eggs are shed in the feces of infected cats. The eggs subsequently sporulate approximately 2 to 4 days later. These 3-day-old, sporulated oocysts—if ingested by some pregnant women—are particularly dangerous to the fetus. Pregnant women can avoid potential exposure to Toxoplasma by taking the following steps:

1. Avoid cleaning cat litter pans when possible, particularly those that contain feces older than 2 days. If it is unavoidable, be sure to wear gloves when handling the litter box and wash your hands when you are finished.

2. Wash raw vegetables thoroughly (dirt on vegetables may contain oocytes).

3. Do not eat raw or uncooked meat, particularly lamb and pork, which can carry the encysted protozoan in the muscle tissue. Cook all meat thoroughly.

4. When gardening, wear gloves that can be removed easily. Under no circumstances should dirt accidentally enter your mouth (e.g., when removing a hair from your mouth).

5. Women in the veterinary profession are encouraged to have Toxoplasma titers evaluated before becoming pregnant, if at all possible. Your physician can give you more specific advice about Toxoplasma titers during your pregnancy.

Other zoonotic protozoal agents, such as Giardia and coccidia, cause diarrhea and gastrointestinal cramping in humans. These are typically spread to people from their contact with infected animals (particularly puppies and kittens), but they can also be acquired by drinking contaminated water.

Because you will probably come in contact with some of these diseases in your job, particular attention to personal hygiene and sanitary work practices is essential. Good personal hygiene includes making sure your clothes do not become soiled by chemicals or biologic material and, of course, regular hand washing. In general, you should wash your hands:

NONZOONOTIC DISEASES

Some infectious agents, such as parvoviral enteritis in dogs and panleukopenia in cats, are not a serious concern to human health, but they are so highly contagious that you can carry the live virus home to your pets on your clothes and shoes. For this reason, some technicians when working with parvoviral cases at work leave their shoes outside their front door and change their clothes immediately upon entering their home, and some even change clothes before they leave the hospital. In addition, technicians who work with cats that have certain viral upper respiratory conditions and chlamydia can themselves contract pinkeye or conjunctivitis. Therefore when treating cases with contagious diseases, be sure to wear a protective apron, surgical mask, examination gloves, and, when appropriate, eye protection. Thoroughly wash your hands with a disinfecting agent, such as chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine scrub, at the completion of the treatment and change your clothes before handling your own animals.

A DIRTY MOUTH? PRECAUTIONS FOR DENTISTRY OPERATIONS

Dental procedures that include use of a high-speed and ultrasonic scaler aerosolize oral microbes, making personal protection a necessity. One of the most common pathogens in the mouths of animals is Pasteurella multocida, an organism that has been linked to cardiac and pulmonary problems in humans and animals alike. Therefore when performing dental procedures, be sure to wear goggles, gloves, and a surgical mask (Figure 6-12).

RADIOLOGY

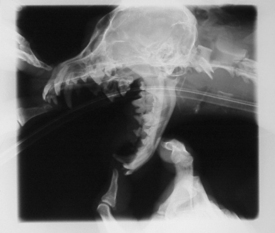

The ability to “see inside the body” is a great tool in medicine. In most cases, the method of choice is diagnostic radiography (x-rays). Short-duration, infrequent exposure to radiation, such as having radiographs taken of yourself, is considered an acceptable level of exposure (the benefits outweigh the risks). However, long-term exposure to low doses of radiation has been linked to many medical disorders. High-dose exposure can cause skin changes, cell damage, and gastrointestinal and bone marrow disorders that can be fatal. Fortunately, much is known about the properties of x-rays, and we are clear about the ways in which we need to protect ourselves. By following some simple safety precautions, you can safely use radiography in your practice.

Although modern radiographic machines have many safeguards integrated in their design, there is still the possibility of injury if these tools are used incorrectly. When you are taking x-rays, always wear a lead apron and lead gloves. Lead thyroid collars and lead glasses are also recommended, particularly during extensive studies, such as with fluoroscopy. Though restraint of animals during radiographic studies can be challenging, never place any part of your body, even a gloved hand, in the primary beam (Figure 6-13).

FIGURE 6-13 Never place your hand or any other part of your body in the primary beam when taking radiographs.

Before you use an x-ray machine, make sure you know the purpose of every knob and button. Always use the collimator to restrict the primary beam to a size smaller than the size of the cassette—in other words, “cone down” to the area to be radiographed so that scatter radiation is minimized. A properly collimated radiograph will have a small clear border around the entire film once developed.

Always follow the written operational and safety procedures from the hospital or machine manufacturer. If you have not already done so, make an exposure chart specific to your machine so that you can replicate the best techniques for various studies. By following a proven technique chart and positioning the patient correctly the first time, you will have fewer “retakes” and will therefore reduce unnecessary exposure.

Portable machines, such as those used in large animal and mobile practices, can be particularly dangerous because of their multipurpose abilities. These machines can be aimed in any direction, and because of their limited power, they must use longer exposure times to produce diagnostic images. When using a portable machine, always make sure no one is in the path of the primary beam (even at a distance). Always use a cassette-holding pole and never hold a cassette with your hands while the exposure is made—even with gloves. Remember to wear a lead apron and gloves when near the machine during exposure.

If you are involved in the exposure portion of radiography, you must have and use an individual dosimetry badge. This badge is worn on your collar outside your protective apron during radiographic procedures, not as protection, but as a measurement of any incidental radiation you may receive during the procedure. It is important to return the badge to the designated storage location (outside the x-ray area) when not in use. Unless you are taking radiographs, do not wear your badge outside because exposure to sunlight will result in false readings. As a result of the relatively low numbers of radiographs taken in most practices, safer machines, and the use of good protective equipment, most technicians receive little, if any, occupational exposure to radiation.

Radiographic processing chemicals (the developer and fixer) can be corrosive to materials and organic tissues so use protective gloves and goggles when mixing and pouring the chemicals. When using manual processing tanks, stir the chemicals with care and avoid splashing. After handling radiographic developing chemicals, always wash your hands. In addition, it is important to avoid breathing the fumes of the processing chemicals, so make sure there is adequate ventilation in the dark room; generally an exhaust fan is necessary.

Radiographic developing solutions can react dangerously with other chemicals. For this reason, never pour chemicals down the drain with developing solutions. Some liquid drain openers, when mixed with developer and fixer solutions, can produce toxic gases. Others can produce an exothermic reaction (generates high temperature) that can damage pipes.

ANESTHESIA

Anesthesia is as common to veterinary medicine as antiseptic wound care. The National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) estimates that more than 250,000 U.S. workers are at risk from exposure to waste gases that are not metabolized by the patient. Long-term exposure to waste anesthetic gases (WAGs) has been linked to congenital abnormalities in children, spontaneous abortions, and even liver and kidney damage.

Although the recent development and use of improved WAGs have lowered risk to patients and health care workers, there is no chemical that is entirely without risk. We must therefore continue to take precautions to protect ourselves, even when using isoflurane and sevoflurane. OSHA has established a safe exposure limit for all halogenated anesthetic agents that is not to exceed 2 parts per million (ppm).

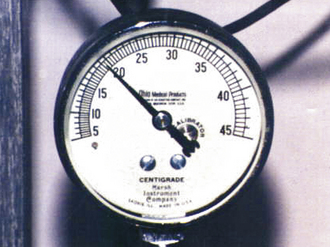

Using a proper scavenging system is the single most effective means of reducing exposure to WAGs. There are three general types of scavenging systems: active scavenging, passive exhaust, and absorption. Each has a place, but rarely does one method fit all circumstances. Regardless of the system chosen, make sure it is fully operational and in use before turning on the anesthesia machine. If you use absorption canisters, be sure to check them (by weighing with a gram scale) regularly and replace them as needed. Once the canister becomes saturated with gas, it is ineffective.

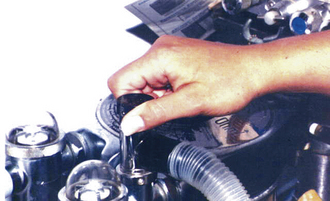

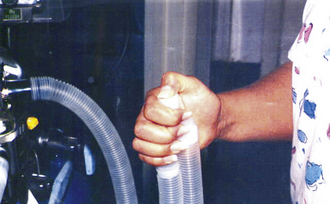

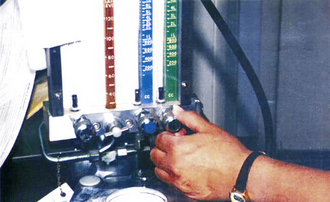

According to some research, as much as 90% of the anesthetic gas levels found in the room during a procedure can be attributed to leaks in the anesthesia machine, so be sure to perform a leak check before use (Box 6-3 and Figures 6-14 to 6-17). Also make sure that the correct size hoses and rebreathing bags are used. Intubation tubes should be placed and the cuff inflated before connecting the animal to the anesthesia machine. Start the flow of anesthetic gases only after the patient is connected to the machine. When the surgical procedure is finished, turn off the vaporizer and increase the flow of oxygen to the patient. Be sure to use the “flush” feature to purge the circuit before disconnecting the patient.

FIGURE 6-17 Step 6: Observe the pressure in the system on the manometer and watch closely for any decrease.

Before filling the vaporizer, move the anesthesia machine to a well-ventilated area. Use a pouring funnel and be careful to avoid overfilling the vaporizer or spilling the liquid anesthetic. If you accidentally break a bottle of anesthetic, immediately evacuate all nonessential people from the area. Any windows in the area should be opened, and all exhaust fans should be turned on. Quickly control the liquid with a generous amount of kitty litter, and place a plastic bag over the spill to reduce evaporation. Pick up the absorbed liquid and kitty litter with a dust pan, and place it inside a plastic garbage bag. Seal the bag tightly and dispose of it in an outside trash can. Leave the exhaust fans on and the windows open until you are sure the gas level has been reduced to a safe level.

The anesthetic protocols that involve masking the patient or using a tank for induction are more likely to generate a larger amount of WAGs. When using these protocols, be sure to use an appropriate flow rate and proper reservoir bag for the size of the patient—do not turn up the oxygen flowmeter to maximum when masking a patient. Induction chambers should always be connected to the scavenging system or absorption canisters to reduce the levels of escaping gases. Make sure the ventilation in the room is good and use local exhaust fans when available.

Anesthetized animals do not metabolize all of the anesthetic gas that they have inhaled. They exhale some of it into the room after they have been extubated and while they are recovering. When monitoring patients during their recovery, you should avoid putting your face close to the animal’s face. In addition, keep the number of recovering patients to an acceptable number based on the size of the area and ventilation system (Figure 6-18). As much as possible, delay extubation and allow the patient to recover while still connected to the anesthetic machine (oxygen only) and scavenging system.

FIGURE 6-18 Monitor recovering anesthesia patients “at arms length” to minimize exposure to gases emitted during respiration.

When changing the soda lime (carbon dioxide absorbent) in anesthetic machines, wear rubber or latex gloves. When the soda lime is wet, as is often the case from humidity in the system, it can be caustic to tissues and some metals. Dispose of the used soda lime granules in a plastic trash bag as regular trash.

Pregnant women should discuss the risks of exposure to anesthetic gases with their physician. In addition, they should inform their supervisor of their condition as soon as possible so that safety procedures can be reviewed and adjusted, if necessary.

COMPRESSED GASES

Every year, hundreds of workers are injured while working with compressed gas cylinders, usually because of improper storage or handling of these cylinders. Regardless of the size of the cylinder or whether the cylinder is empty, full, or in use, store them in a dry, cool place, away from potential heat sources, such as furnaces, water heaters, and direct sunlight. Always secure the tanks, even the small ones, in an upright position by means of a chain or strap (Figure 6-19). Cylinders that are stored inside a closet should also be secured since they can fall against the door and cause injury when you open the door. If the cylinder is equipped with a protective cap, they must be firmly screwed in place when the cylinder is not in use. If you have to move a large cylinder, do not roll or drag it; always use a hand truck or handcart, and remember to strap the tank in.

SHARPS AND MEDICAL WASTE

The most serious hazard from needles or sharp objects in a veterinary medical environment is from the physical trauma (and possible bacterial infection) that is caused by a puncture or laceration. To prevent these types of accidents, always keep sharps, needles, scalpel blades, and other sharp instruments capped or sheathed until ready for use. Do not attempt to recap the needle after use unless the physical danger from sticks or lacerations cannot be prevented by any other means. When it is necessary to recap a needle, you should use the “one-handed” method (Box 6-4 and Figures 6-20 to 6-22). Although some practice is needed before the one-handed method becomes second nature, it is the safest and most practical approach for most veterinary situations.

FIGURE 6-20 Using only one hand, hold the syringe in the tips of your fingers with the needle pointing away from your body.

Do not remove the needle from the syringe for disposal because this unnecessary handling often results in injuries. Whenever possible, the entire needle and syringe should be disposed of in the designated sharps containers immediately after use. Do not try to overfill a sharps container—when it is full, it is full! When the sharps container is full, seal it and replace it with a new one. Never open a sharps container that has already been sealed or stick your fingers into one for any reason.

Destroying the needle before disposal is not recommended because it may aerosolize the contents of the needle and increase your exposure. Likewise, you should not collect sharps in a smaller container and transfer them to a larger container for disposal. Of course, never throw needles or sharps directly into regular trash containers, regardless of whether or not they are capped.

Table 6-1 explains which materials are usually considered hazardous and which are not. Although this chart is essentially accurate, some states have special rules for discarding medical waste, so be sure to follow the rules prescribed by your state.

TABLE 6-1

Typical Medical Waste Definitions

| Material | Medical Waste | Normal Trash |

| Sharps (any device with characteristics that make it possible to puncture, lacerate, or penetrate the skin) | Any used needles and scalpel blades Glass or hard plastic that is contaminated with a human disease–causing agent | Glass or hard plastic that is not contaminated with human disease–causing agents can be disposed of as normal waste. |

| Medical devices such as blood tubes, vials, catheters, IV tubes, etc. | Considered biomedical waste only when they contain human pathogens or they have been used for chemotherapy | Devices that simply contain or are contaminated with animal blood (except from primates) are normally not considered biomedical waste. |

| Animal blood or tissues | Only dead animals or animal parts that are infected with diseases that are communicable to humans; this includes but is not limited to rabies, brucellosis, systemic fungal diseases, tuberculosis, atypical mycobacteriosis, etc. | Tissues from routine surgical procedures (castration, ovariohysterectomy, etc) should be considered regular waste. |

| Laboratory cultures | Microbiologic cultures (bacterial, fungal, or viral) of human pathogens are considered biomedical waste | In some cases, culture media from negative tests may be considered regular trash, but it is probably wise to just classify all lab cultures as biomedical waste for simplicity. |

| Bandages/sponges | Used absorbent materials such as bandages, gauze, or sponges that are saturated with blood or body fluids that contain human pathogens that may splash or drip | Sponges or bandages used on animals not infected with a disease transmissible to humans. |

| Primate materials | Normally, waste generated from work on primates is considered regular waste unless it fits in another category (such as from research studies using human pathogens). | |

| Animal waste | Waste from animals infected with a disease contagious to humans that can be transmitted by means of the waste. Waste from chemotherapy patients for up to 48 hours after the last treatment | Normally, waste from animals not infected with human disease–causing agents should be disposed of as regular trash. |

HAZARDOUS DRUGS AND PHARMACY OPERATIONS

Medicines are designed to cure diseases and make patients better, but it is important to remember that all medicines are chemicals and chemicals can be dangerous. In the veterinary pharmacy, you can be exposed to all kinds of drugs just by handling them. Liquids can splash in your eyes when you pour them or they can release vapors that you can inhale. Handling, crushing, or breaking tablets can leave powder residue on your hands that will be ingested next time you put your hands near your mouth or mucous membranes.

Some drugs, such as the cytotoxic drugs (CDs) used to treat patients with cancer, are so potent even minute exposures can cause harm. When preparing CDs, always wear powder-free chemotherapy gloves and a disposable gown that is not used for any other purpose. Chemotherapy drugs should always be mixed inside of a biologic safety cabinet (Figure 6-23). Be sure to follow all of the instructions on the MSDS, package insert, and your practice’s chemotherapy safety plan.

During the administration of CDs, expect the unexpected. Keep unnecessary people out of the area and wear protective equipment such as gloves, disposable aprons, surgical masks, and eyeglasses. You should avoid wearing contact lenses when preparing or administering CDs.

When handling patients that have received chemotherapeutic treatments, remember that some drugs are excreted in bodily fluids, so proper precautions are necessary when cleaning up their urine, feces, and other bodily excretions. Always wear powder-free chemotherapy gloves and avoid contaminating your clothes when cleaning cages or picking up waste from chemotherapy patients. Make sure you dispose of all soiled materials from these patients as medical waste and launder nondisposable items separately from general laundry.

The biggest rule to remember when handling any medication is to practice good personal hygiene, especially a thorough hand washing.

SUMMARY

We all face dangers in life every day, but that does not mean we have to intentionally place ourselves in danger to get our job done. The successful person makes sure the reward for the action far outweighs the risk.

In this chapter, we discussed your rights and responsibilities in a safety program, the hazards associated with your job from both a general and medical perspective, and the actions you should take to protect yourself. Employing good safety practices should not be the cause for additional work. If a job is safely completed and the correct protocol is followed, then it is done properly. Occupational risks should not keep you from doing your job; they should motivate you to do your job better, to pay attention to what you are doing, and to comply with the standard operating procedures established in your practice. Employing good safety practices will enable you to remain healthy and will therefore allow you to continue to practice your career for a long time.

INTERNET RESOURCES/SUGGESTED READING

SafetyVet: www.safetyvet.com

OSHA: www.osha.gov

Canadian OSHA: www.canoshweb.org

National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH): www.cdc.gov/niosh

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: www.cdc.gov

Canadian Centre for Occupational Health & Safety: www.ccohs.ca

The Veterinary Information Network (VIN): www.vin.com

The Veterinary Support Personnel Network (VSPN): www.vspn.org

Infection Control Today: www.infectioncontroltoday.com

The Virtual Anesthesia Machine: http://vam.anest.ufl.edu/

Lab Safety Supply: www.labsafety.com

Environmental Protection Agency: www.epa.gov

Department of Labor: www.dol.gov

TECHNICIAN NOTE

TECHNICIAN NOTE