Restraint and Handling of Animals

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

1 Discuss the indications for restraint of animals and behaviors exhibited by aggressive animals.

2 Explain the physiologic principles that affect animal perceptions and methods of restraint in small and large animals.

3 Describe the methods for approaching, haltering, tying, and leading equine patients.

4 Define twitch and describe various types of twitches and their uses in equine restraint.

5 Explain the methods used for lifting a horse's foot, applying a tail tie, and applying hobbles.

6 Describe the indications and procedures for the use of stocks in equine patients.

7 Describe the indications and procedures for moving cattle and sheep into pens and chutes.

8 Describe the procedures for tail jacking and casting of cattle.

9 Explain the methods of capturing individual sheep, goats, and pigs.

10 Describe the proper procedures for carrying and lifting large dogs, small dogs, and cats.

11 List and describe the types of muzzles and mouth gags that are used on dogs and cats and explain the proper procedures for their use.

12 Describe restraint and handling techniques used with birds, reptiles, and amphibians.

13 Describe restraint and handling techniques used with ferrets, rabbits, and rodents.

14 Discuss the indications for use of chemical restraint in animal patients.

INDICATIONS FOR RESTRAINT

Competent restraint of animals is critical to a veterinary practice for the following reasons:

1. To control an animal so that it can receive medical care. Most animals resist physical examination and the administration of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Proper restraint of a sick animal may allow humans to save its life.

2. To prevent the animal from harming itself while it is receiving medical care. Animals must be restrained when panicked and trying to flee from, what they perceive as, a dangerous situation. Jumping off an examination table, attempting to crash through a fence or chewing the bars of a confinement are examples of fleeing behavior that can have disastrous results. Maintaining a safe environment, including well constructed stalls, cages and fencing is a critical part of protecting the animal from injury.

3. To protect personnel. The safety of veterinary personnel, clients and handlers is of the utmost importance. The injury and even death of individuals can devastate families, and veterinary practices. It can lead to the loss of wages, expensive litigation, anxiety, decreased morale, and loss of livelihood. Practice owners are responsible for any injuries incurred by veterinary personnel and clients during the performance of veterinary procedures. This liability begins when the client enters the practice or when the truck stops in the driveway. For this reason, many practitioners believe that a veterinary technician’s ability to perform excellent animal restraint is the most important skill for a technician to master.

ANIMAL PERCEPTION AND BEHAVIOR

Current studies in behavioral science and ethology provide us with information on animal-to-animal communication that aids in the understanding of how best to restrain various species. This data improves the ability of humans to assess animal responses and better understand how our interactions affect an animal’s behavior. Animals employ their senses, such as sight, smell and hearing, in ways that are different from humans. Therefore, animal gestures, touches, smells and actions that provide important information to other animals is often missed or misinterpreted by humans. A veterinary technician’s ability to correctly interpret these non-verbal, species-specific forms of communication is critical for implementation of effective and compassionate restraint.

SMELL

The sense of smell is well developed in all domestic mammals. The rabbit and cat have improved olfaction because of olfactory epithelium that is nearly 14 times more developed than in humans.

Horses will snort when faced with a smell with which they are unfamiliar. Bulls may react by pawing and blowing when they are faced with a different smell. We now are more aware of the chemical changes that occur in the human body which may cause changes in scent that communicate illness, stress and anxiety. Consider, for example, that we now train dogs to detect cancer in humans because the illness alters metabolic chemistry.

The language of smell undoubtedly has a more extensive vocabulary in animals than in humans. This is important to acknowledge when handling various species in a single hospital setting such as an exam room or treatment area. For example examinations of prey species such as rats, rabbits and mice should not be done in an area where a cat was recently examined. The finely tuned scent organs of the prey animals will detect the scent of a predator which may increase blood cortisol levels and alter heart and respiratory rates. Other odors to consider that may affect an animal’s behavior are anal sac excretions, vaginal discharge from intact female dogs or urine from a mare in estrus.

HEARING

Domestic animals are able to move the external ear, or pinnae, with muscles, which enables them to focus on the source of the sound. This is advantageous because an approach by a handler is often observed. Slight sounds will elicit movement of the ears and allow the animal to become aware of the presence of someone new. Low, smooth, confidant tones will allow the animal to become comfortable with your presence. The response of the ear is important to assess the animal’s attitude. The ears-back position in a horse or llama signals that the animal is upset or aggressive. A dog pricks its ears forward when alert or actively aggressive, whereas a submissive dog wrinkles and flattens its ears. Cats with their ears pinned back should be considered dangerous. Alterations in the shape and size of an animal’s ears may decrease the ability of the handler to use ear position as a sole indicator of the animal’s state of arousal.

VISION

The eyes of domestic animals focus by means of muscles controlling the shape of the lens through a process called accommodation. In small animals and pigs, accommodation is accomplished by increasing the dioptic power of the lens by changing the shape of the lens. Most animals accommodate the eye on near objects much less readily than do humans. It is known that the nearest point at which dogs can focus is about 30 cm, and this is most likely true for the pig. The dog’s ability to discriminate form and pattern is thought to be poor when compared with human abilities. This is particularly important when dealing with those dogs that are noted to be “fear biters.”

Cats have excellent night vision, which is consistent with their nocturnal habits. They are also acutely aware of a small movement, which facilitates the precision of their rush after stalking their prey. Unfortunately, this also enhances the ability of a fearful or painful feline patient to strike out against those humans who move too suddenly or come too close.

The pig has eyes that are directed more forward than the horse, but less than that of most dogs. The size of their binocular visual field could be as large as 30 degrees on either side of the midline. Ruminants have much less ability to accommodate with the lens of their eyes and will therefore have a much longer near-focus distance. Herbivorous animals have wide fields of vision enabling them to detect the encroachment of predators from various angles. This is particularly evident in the horse and rabbit, both of which enjoy nearly circumferential vision without moving the head. The horse has a particularly sluggish accommodation. What some handlers may perceive as fractious and spooky may in fact be nothing more than the horse attempting to visually accommodate. This is particularly noticeable when an already nervous human makes fast movements near a horse. The horse moves about in a rapid manner trying to ascertain what the human wants. Horses have acute vision at middle and far distances, which is not surprising for a prey species. Many of the behavioral displays of horses are visual in nature, and subtle movements by handlers at seemingly great distances will generate responses from horses. It is assumed that the binocular segment of the visual field for a ruminant is about 30 degrees on either side of the midline.

TOUCH

The sense of touch is becoming more important in the handling of animals. Numerous behaviorists and trainers are proponents of contact on different body parts to enhance communication between animals and among animals and humans. Contact behaviors that appear to result from or resolve conflict are the ones most described in handling. Dominant animals use biting, scratching, kicking, or striking to teach youngsters proper behavior. Horses kick or slam a shoulder into other horses to demonstrate dominance and make a point of their supremacy. Mares training youngsters in a herd will actually keep a particularly hardheaded yearling out of the herd by biting and kicking at it. This communication is species specific and it is best to avoid attempts to replicate these behaviors. It is important to remember that these behaviors occur in specific contexts and may relate to control of resources. Some people will use blows to correct unacceptable equine behavior. When using these techniques, the target must be carefully selected, and the individual must possess the physical strength to make the procedure effective. As a general rule, humans will end up hurting themselves much more than the horse they were trying to correct. It has also been shown that physical correction for behaviors can create fear, stress and anxiety for the animal in addition to damaging the human-animal bond.

The actual method of how to touch animals is a manner of skill. Tentative, light touches or repeated patting makes many species nervous and apprehensive. Steady, firm strokes are reassuring to most species. Watching animals in a natural setting provides the insight into how to most effectively touch them when they are nervous. You will never observe one animal slapping another to calm it down in a natural setting. Clever individuals learn to read the animals that they are asked to restrain and develop the touch necessary to keep them calm.

AGONISTIC BEHAVIORS

Agonistic behaviors are those associated with conflict. Many animals have to be maneuvered into a position in which restraint is possible, or they must be restrained from the outset as a safety measure. Such maneuvering is perceived by the animal as conflict (threat). To understand the principles of maneuvering each species, it is wise to become familiar with the prevalent forms of agonistic behavior in the different species. Agonistic behaviors cover the range of responses to conflict from passive avoidance to the extreme of aggression and fighting. In nature, overt aggressive attacks that lead to fights with other animals of the same or different species are not common outside of sexual or predatory behavior. Dominance and submissive behaviors represent the more common methods of resolving disagreement over resources such as food, territory, and reproduction. Chapter 11 gives additional information on animal behavior.

Fight or Flight

When a stranger approaches an animal, the same basic principles apply whether it is a domestic or wild animal. Each species in a given environment has its own degree of response, but the factors or cues giving rise to the response are common to all animals in varying degrees. Each animal has a fight-or-flight distance. When that space is invaded, the animal goes into a state of alert. The sympathetic nervous system releases epinephrine from the adrenal gland. This hormone causes increased heart rate and a subsequent increase in blood flow to the skeletal muscles, lungs, and brain. Further encroachment into the animal’s space will lead to action that may take the form of avoidance (the cow or horse crash through a fence, the dog runs off down the road) or aggression (the dog bites, the cow runs over the stranger). This action is aptly termed the fight-or-flight response. The response will vary from animal to animal of the same species and may vary from time to time for the same animal. When this happens, it is difficult to come up with a good restraint plan.

AGGRESSIVE BEHAVIOR

Aggressive behavior is the form of agonistic or conflict behavior that leads to and includes fighting. Aggression is not the result of a single cause. The different forms of aggression are classified according to the stimuli or circumstances giving rise to the ferocity.

Irritable or Pain-Induced Aggression

Inevitably, pain-induced aggression is a common problem in the veterinary hospital and in field situations. Herd animals that have become incapacitated and are incapable of keeping up with the herd must resort to aggression to stay alive. Injections and certain manipulations, such as the treatment of wounds, cause pain and discomfort to animals. Even the initial injection of a local anesthetic can be most uncomfortable, no matter how skilled the anesthetist. The state of mind of the patient has a lot to do with an aggressive outcome. If the animal is initially apprehensive and nervous, the probability for aggression is high. This is the reason that calming and familiarization of the patient are practiced whenever possible. Sedation may also be indicated for certain patients.

Maternal Aggression

All female domestic animals that are suckling their young are sensitized to interference with their offspring by strangers. The calmest, old broodmare in the herd may be extremely protective of her new foal. The bitch can be aggressive with strangers and even family members if she perceives a threat to her pups. A sow within earshot of her piglets when they are being restrained can become one of the most dangerous animals encountered. All parties working within a farrowing house must exercise caution because the vocalization of any young piglet as it is manipulated can make all the sows in the house become sensitized.

Predatory Aggression

Aggressive activity displayed by chasing and killing prey is observed in predatory domestic animals, such as the dog and cat, and is called predatory aggression. This form of aggression does not usually pose a threat to the animal handler, although large dogs may pull the handler down if they feel the urge to chase a cat while on a leash.

Territorial Aggression

All domestic mammals have a degree of territorial domain. They will protect the area over which they range from intruders, and they may exhibit territorial aggression. Separate groups of horses may share feeding sites and watering holes, but they remain apart from one another and retain control of their own separate home range. The domestic dog may regard the yard, porch, or house as its territory. Strangers are treated with suspicion, and this suspicion may lead to barking or attack. Unfortunately, territorialism in dogs can be difficult to distinguish from behavior that has been conditioned, is related to fear, lack of socialization or lack of mental stimulation. Dogs that harass the mail carrier or meter reader are behaving within the norm of canine behavior. The female rabbit is strongly territorial in the captive situation. If a buck is taken to her cage, she will attack him aggressively, often causing serious injury. Thus the doe is always taken to the buck’s cage for mating. This female territoriality may be associated with aggression that continues even when the nesting box is empty and can be directed at humans. Although the concept of an “attack rabbit” may seem humorous, it becomes less so when reaching into the cage of an old doe and being growled at, struck, and bitten.

Fear-Induced Aggression

When an animal is terrified of an environment and the people in it and is not given an option to avoid the circumstances, it will resort to aggression. Fear is a common cause of aggression in dogs placed under such circumstances. Fear biting is the most commonly encountered type of attack in veterinary hospitals. The dog is usually giving classic signs of being intimidated: avoiding direct eye contact with the head down, lips pulled back horizontally, ears flattened, and the tail between the legs, which have been ignored or misinterpreted by human handlers (Figure 7-1). When the personal space of such a dog is encroached, a sudden attack may ensue. This is fear biting. The attack is usually confined to the proffered hand or forearm, and the purpose is simply to repel the invader.

Intermale Aggression

Aggression occurring between males can be a problem, particularly when stud animals are kept. Boars can be extremely vicious when confronting each other, and great care should be taken when handling them. Stallions can become extremely agitated when mixed with another stallion. Bulls spend a great deal of time head butting and pushing one another around to establish the dominance order when they are turned out together.

Dominance Aggression

In the past it was presumed that certain dogs would establish their authority over a human family, other animals, and strangers because of their heritage as pack animals. Alternatively a dog may accede to dominance from one family member, but attempt to assert itself aggressively with other family members. Current scientific data refutes such arguments. Past assumptions were made by observation of wolves which were then applied to domestic dogs. Animal behaviorists, both in veterinary medicine and university settings no longer use the term dominance aggression due to the incorrect assumptions of the past.

Information collected by modern day animal behaviorists and ethologists shows that dogs while genetically related to wolves, differ in behavior. The effects of years of domestication and breed selection for specific characteristics have yielded results that favor the dog’s ability to live among humans. Additionally, original theories on dominance as a whole did not take into account how human interactions alter the behavior of domestic species. For example, old theories on dominance would say that when a dog jumped up on a human the dog was asserting its dominance. However, if the owner pets the dog when it jumps on them then the behavior is not dominant at all but has been conditioned of “trained” by the human. From the dog’s perspective it jumps on the human in order to receive contact and be petted.

In today’s world of veterinary behavior the term dominance aggression would most likely be related to a conflict between two animals regarding resources. Aggression would be the resulting behavior if neither animal was willing to give up the resource. An example of this would be two stallions competing for a band of mares.

TYPICAL BEHAVIOR OF DOMESTIC ANIMALS IN AGGRESSION AND AVOIDANCE

The primary concern when dealing with cattle is bulls, regardless of size. Dairy breed bulls, such as the Jersey and Holstein, should be considered the most dangerous animal of all the species that veterinary personnel are asked to restrain or handle. They are powerful and unpredictable. Aggressive behavior is characterized by pawing the ground with the forefeet while holding the head with the frontal area nearly vertical with the ground and snorting. These bulls after charging and knocking the person down will make continued attempts to toss the victim, which will lead to goring if the bull still has horns. Bulls may also attempt to kneel on the victim or continually smash the victim with their foreheads. Little can be done to dissuade or thwart a bull once this activity begins. Front-end loaders and pickup trucks have been used to try to push these animals away from their targets without success. Bulls, particularly the dairy breed types, should always be treated with the utmost respect and with the appropriate means of restraint and containment. The likelihood of a snorting bull, posturing in an aggressive stance, hurting a handler is actually less than one that has been hand raised. The hand-raised bull may appear to be quite gentle and yet when approached may react aggressively. Special handling considerations are made for those who work with semen donors at bull studs. These bulls are selected for the high-quality genetic potentials, and their semen is worth considerable amounts of money. Insensitive handling before and during collection may give rise to reproductive behavior problems leading to decreased collection volumes and significant economic loss.

Aggressiveness in the heifer and cow seems to be directly related to breed and socialization. Dairy cows are generally docile, probably because they are handled a great deal. Beef cows that have been handled frequently in a quiet, professional manner are manageable. However, beef cattle that are raised on range with little human interaction or those that are handled with lots of whipping and shouting tend to be apprehensive and may become quite aggressive. This aggressiveness is compounded when they are nursing calves.

The fight-or-flight distance for a herd of cattle will vary depending on the previous degree and type of contact with humans. The handling of dairy cattle and beef cattle differs greatly. The flight distance for dairy cows is extremely short, with the animal veering off only when directly confronted by the handler. Most dairy cattle are used to a number of different people around them during milking time, and the introduction of someone new into the herd does not create stress or fear. This makes handling dairy cows easier for veterinary personnel. Beef cattle have a much larger flight space, which is accentuated when they sense a new presence in a field or pen. It is common for ranchers to be able to walk or drive among their cattle at close range. When a new pickup or person enters the pasture, the cattle’s heads come up and they will gradually move further away. If the cattle are approached too quickly, they will break into a disorganized run, which makes them nearly impossible to maneuver. It is important to realize the impact that outsiders have on a herd of beef cattle before trying to handle and examine individuals. This is a common problem in “Penturbia,” where owners get two pregnant cows to decorate their acreage (usually of 3 to 5 acre lots) and then need veterinary attention. Routinely, they do not have adequate handling facilities on site. It is extremely important for veterinary personnel to understand this before initiating procedures to capture the animals in a run-in shed or a makeshift corral.

A part of the secret of maneuvering cattle is using a body extension. Canes, stock whips, or wiffle paddles used by a person on foot are viewed by the cattle as an extension of the body. If the cattle can be kept calm, the visual barrier created by these devices allows the handler to maneuver the cattle from pen to pen. If cattle are accustomed to observation from horseback, maneuvering a herd can be quite easy for one or two riders. Mixing riders and walkers in a pasture is not a good idea and should only be done as a last resort when trying to maneuver a herd of cattle. It should be made clear that maneuvering the herd (or all the animals that are housed together) is much easier than attempting to separate an individual.

Calves

Calves are inquisitive and will become attentive to the presence of someone new. The calf stretching its head or neck toward the new handler is the usual posture (Figure 7-2). Darting movements will cause the calf to panic, veer, and run away. The approach toward a calf should be slow and deliberate with the hands slightly away from the sides of the body. No loud noises are necessary, and movement of the hands and arms should be kept to a minimum. Using a fence line or wall, the handler should move to cut off escape routes and negotiate the calf into a corner and grab it with one arm under the jaw, and the other hand should reach and grab the tail.

Cats

Aggressive behavior in cats should never be underestimated. They can be formidable patients in situations of conflict because they will use the claws of all four feet, they have razor-sharp teeth, and when stressed they seem to have a spinal cord that is made much like a Slinky, which allows them to go in many different directions at once. It should be remembered that the cat stalks its prey and runs only short distances to pounce. It is a stealthy aggressor. The true speed of the cat never becomes apparent until it is actively avoiding conflict. It is the wise staff that closes all doors and windows before attempting to handle cats in any environment to prevent escape.

Dogs

Overtly aggressive behavior, although not a common problem in dogs, is a significant social problem and one that will present difficulties for veterinary personnel. Dominance and submission are important in communication between two dogs in a conflict situation. Fixing the other animal in a direct stare is a direct threat of aggression. The ears are raised and angled forward. The front end of the body is held high, and the hackles on the back of the neck are raised. The head is held up, and the lips curl to reveal the incisor and canine teeth. The tail will be raised. The clinical stare of veterinary personnel as they examine a dog can be taken as a threat of aggression by a dog.

Lowering the front end of the body and avoiding direct eye contact demonstrate the submissive behavior. Usually the tail will be held between the legs, and the dog may squat and urinate or defecate. The ears will flatten on the back of the head, and the lips may become pulled back at the corners of the mouth into a “grin.” The spine may adopt an S shape, and the animal may lie down on its side or back, raising the legs and exposing the undefended belly. When dogs display this behavior it is similar to saying “take my keys and wallet, please don’t hurt me.” These behaviors are designed to appease an aggressor which would decrease or diffuse conflict between dogs. In the veterinary clinic this behavior is commonly demonstrated by fearful or anxious dogs.

When confronted by a person, the dog may demonstrate potential aggression by adopting the aggressive posture, or it may adopt a submissive stance. A dog in the active aggressive posture may attack if the threat is not removed from its fight-or-flight distance. A dog in this posture will bite if you attempt to encroach on its space. Dogs demonstrating submissive postures may also bite when handlers reach into their space or lean over them accidentally increasing the dog’s fear. Some dogs may show active aggression only when the owner is present. The protectiveness may be possessiveness as the dog defends its own favored object, owner conditioned behavior, or specifically trained behavior (protection/security dogs). Removing the owner may resolve the conflict. The opposite may occur when handling dogs that have developed a bond with their usual handlers. These dogs may be quite fearful without their human partner in the examination room. Retrievers, herding dogs, and guard dogs that tend to associate closely with only one individual may be quite difficult to handle without their owner present.

Certain dogs do not attempt to resolve conflict by aggression, preferring to avoid it if at all possible. Those that skillfully avoid conflict are described as having a passive defense reflex. Dogs that tend to face conflict are said to have an active defense reflex.

Horses

Blatant aggressiveness in the horse is not common. However, certain horses can be nasty with their aggression. This is most commonly seen in horses that are stalled most of the time. Racehorses and breeding stallions seem to be the worst offenders. Aggressive behavior may be observed on broodmare farms with mares protecting new foals and stallions protecting their band of mares. Lunging forward and biting, kicking with the hind legs, and striking with the front legs characterize the aggressive acts of the horse. Although the field of vision of the horse is nearly 360 degrees, the binocular field of vision is only 60 degrees to 70 degrees in front of the animal. Binocular vision is required for judging distance; therefore vision outside this range requires movement of the head and sometimes the entire body to allow the horse to further investigate what it perceives as the threat.

The approach to a horse should not be made from the blind spot directly behind the horse. The horse, as it detects new objects or people in its environment, will raise its head and observe. If no threat is perceived, the horse resumes its previous activity. If the threat is perceived as real, the head turns toward the object, the neck is raised, and the ears will turn toward the object. The nostrils will become dilated to further evaluate the threat. The tail will also become elevated, and the muscles of the torso and lower limbs will become more rigid, ready for fight or flight. Occasionally the horse will snort, further alerting other horses to the presence of a threat. Mares with foals will usually nicker, and the foal will move to the other side of the mare. Further encroachment results in rapid movement away from the intruder. If the horse is in a stall, it will circle rapidly away, always keeping its hind end toward the intruder.

Pigs

Aggressive behavior in the domestic pig has serious economic and physical consequences. Adult boars that are mixed together will circle and threaten each other with grunts and jaw snapping. Fighting commences in the side-to-side position with sideways pushing and slashing at one another with the tusks. Solid panels of plywood should be used to separate the combatants. Commercial pigs are reared in groups, which provide plenty of opportunity for fighting. When new pigs are introduced into a group, fighting will occur, especially if living space and trough space are limited. Introducing a sow into an established group may induce savage attacks and even deaths. Allowing more space and diversions for the group reduces aggression in pigs.

Large numbers of unfamiliar pigs adapt better than smaller numbers. There is less fighting, probably because dominance is more difficult to establish in the larger social groups. Avoidance behavior in young pigs in confined areas involves running into corners and huddling, shoving, and climbing over one another. This does not present a problem if small groups are huddled, but larger groups that pile up may produce traumatic lesions and in severe cases death from suffocation.

Remember that the lactating sow can be extremely dangerous because of maternal aggression. When handling suckling pigs, always remove the sow to a secure area out of earshot, if possible.

Sheep

Avoidance behavior in sheep is the basis of maneuvering the flock. When sheep are approached, they will flock together and move as a single unit. This herding behavior is well understood by dogs. By carefully controlling their posture, speed of movement, and distance from the flock, the dog uses the sheep’s avoidance behavior to maneuver the flock into an enclosure. This is one of the most fascinating and complex interspecies relationships in domestic animal management. Handling areas should be well lighted and free of objects that may project shadows into the sheep’s visual path and should have solid sides.

Aggression between rams may lead to injuries between the combatants. Handling these rams may also be difficult because of the willingness of the ram to challenge the handler. Rams are most dangerous when they attempt to head butt and as such should be treated with respect.

MANAGEMENT ETHOLOGY

Ethology is the study of animal behavior (see also Chapter 11)Capture, handling, and restraint might be called management ethology, which is the study of animal behavior as a means of determining how best to maneuver and control animals. The approach and handling techniques that are described for each species are in harmony with the typical behavior of the animals that we are asked to restrain, and the physical techniques described are compatible with their anatomy. Humans have great powers of observation, and it is important for students of the animal industries to enhance their powers of observation about animal behavior. Knowledge of body systems and anatomic structure is clearly important, but there is no substitute for alertness, observation, and perception of how the animal is reacting to its environment and to the presence of veterinary personnel. Mental preparation must begin well in advance of any potentially dangerous restraint situation. Confidence and knowledge will be gained over time that ensures the handler of a correct assessment of any situation.

CAPTURE AND RESTRAINT OF HORSES

A cardinal rule when approaching any animal, especially a horse, is not to startle it. The handler should always make his or her presence known by talking or calling to the horse. Many horses have learned that capture leads to work or some sort of unpleasantness, and these type of horses will practice avoidance. Horses also do not like to be closely confined or “squeezed.” Close quarters will make many horses anxious, and some will attempt to escape, which may result in injury to the horse and people involved. By calling to the horse, the handler begins to have an appreciation of how a particular animal is going to respond.

The normal flight distance of most horses is between 3 and 10 m. Events that occur outside this radius are of little concern to the horse. Once within this area, sudden movements or sharp noises may easily startle it. Always be sure that the horse is observing you as you approach. A horse that is looking at you is less likely to be startled than one looking off at some other object. Be aware that if the horse decides to become nervous the first evasive maneuver that it will perform is to wheel away, leaving you facing the hindquarters of the animal.

It should be obvious that approaching a horse from the rear should be avoided, if possible. Given the horse’s zone of vision and its blind spot, the horse is not likely to see a person directly behind them. A horse’s kicking zone extends 1.8 to 2.5 m behind it. The furthest extension of the heels is the most dangerous and is the area of potentially fatal kicks to the head or chest. Horses usually kick to the rear, rather than to the side, but many of them can “cow kick,” or kick to the side well. It is wise to grant at least 3 m behind and to the side of a horse when dealing with the rear quarters of the horse. The other alternative is to stay in direct contact with the horse as you maneuver about the hind end (Figure 7-3). Staying close to the hindquarters will not allow the full force of a kick and will keep the force of the blow low on the recipient’s anatomy. This does not mean that the blow will not be painful or damaging. However, a fractured tibia may be some consolation over a fractured skull. Grasping the tail may discourage some horses from kicking.

FIGURE 7-3 Note how the handler maintains contact with the horse as he begins to move from one side of the animal to the other. This is especially important since he is in the horse's blind spot.

The prospective handler should also never stand directly in front of the horse. A horse that becomes agitated may strike out with a front foot and leg at any instant. Agitated horses also may decide to become carnivores at any time and attempt to bite the handler.

The initial approach to the horse is best accomplished from the front and left side (Figure 7-4). The left side in equine terminology is known as the near side. This is the side that the horse is accustomed to being handled from because of tradition and the fact that most people lead their horses with their right hand. The first point of contact for the handler on the horse should be the withers. The handler should have a slightly outstretched arm that is no higher than the handler’s shoulder. The handler should make some low, confidence-building conversation as he or she moves toward the horse. This goes back to the natural behavior of the horse, from mares licking their foals to the social interaction between horses in which they will rub each other on the withers. If the horse moves away, the handler should stop and stay still until the horse has quieted again. Many times if the handler will turn slightly away from the horse and not look directly at it, the horse will turn back to the handler (Figure 7-5). This movement mimics the communication found in herds of horses when an outsider is finally “welcomed” into the herd. It is always wise to move in slow increments without raising your hands or voice. Presenting the hands in an open and empty manner may help the horse to gain confidence. Sometimes it is beneficial to squat down. This works reasonably well with young foals and some horses. The shorter stature probably makes the figure less threatening and increases the horse’s curiosity. Do not rush toward the horse at any time. Horses will assume you are giving chase and continue to move away, and some can become quite panicked. Once the would-be handler is behind the horse, the horse perceives even more of a threat since it cannot see the presumed intruder.

FIGURE 7-4 Initial approach to the horse should be from the left, or near, side. Note the right hand leads to touch the horse at the withers. The left hand holds the halter and lead rope low and to the handler's side.

FIGURE 7-5 Note how the horse's ears and head are directed toward the would-be handler, almost as if the horse wants to know what is going to happen next.

The approach to halter the horse should also be unhurried and without sudden movements. Keeping the lead rope or halter hidden by your side may assist in the capture of the skittish horse. A small-diameter catch rope may aid in the capture of the horse’s neck (Figure 7-6). The rope may be carried up along the neck after gaining the horse’s confidence at the withers by a moment of petting. If the horse moves away, attempt to stay with it by moving along side and holding onto the mane. Most horses will have sense enough to know that you mean business if you stay with them at this time.

FIGURE 7-6 The use of a small rope looped over the horse's neck will aid in controlling the horse's head and allow the handler to place the halter over the nose.

When the horse is standing quietly, loop a rope around the neck by passing the rope over the horse’s neck with the right hand and reaching under the neck to grab the free end with the left hand. When placing the rope over the neck, start as low on the back as possible. Remember that slow and steady movements are the key to success. Once the rope is around the neck, the horse may be held in the loop, and the rope can be maneuvered to the throatlatch area. The halter can be placed by sliding the noseband over the nose and passing the crown strap to the right hand and then bringing the strap over the horse’s head for fastening.

The horse that does not respond to any of the above techniques becomes the biggest problem encountered in a field service practice. The arrival of veterinary personnel may trigger memories of previous contact that the horse does not want to have repeated. The usual reaction is for the horse to move off as far away from the handlers as possible. Of course, the simple solution is to have the horse caught before arrival of the veterinary team. However, this is not always possible. The usual solution to this problem is bribery with a handful or bucket of grain, which will entice the horse to approach or at least be approached. It is best to hold the bribe in the left hand and turn at right angles to the horse so that the neck is within easy reach for petting. As the horse gains confidence with some firm strokes along the shoulder, the right hand can then ease around the neck and allow capture. Many of these horses will attempt to wheel away when the arm is first placed over the neck, and this is where the small rope may be of assistance as a restraint aid. It is desirable to not allow horses to escape the first time because if they do it once they are likely to persist and become even harder to capture the second time. A horse that persists in whirling away becomes a candidate for trapping or, in extreme cases, roping.

Many horses that are impossible to catch in an open field will give up in an enclosed space. However, there are some that become exceptionally nervous in a small area and will kick or try to jump out when approached. The use of another haltered, calm horse within the stall to trap the nervous one will work in a majority of these cases. Similar to catching an unbroken foal, one handler will use the calm horse to trap the other in a corner. Then with slow and steady movements beginning at the withers, the second handler eases up the neck with a rope and makes the loop, which will allow temporary restraint of the nervous horse. A second technique that may be used is to have a solid panel that may be used to “squeeze” the horse into a corner. The panel needs to be sturdy enough to withstand the horse pushing against it and be movable enough to allow the handlers to back away in case the horse “blows up.” This should be used as a last resort in attempting to capture the nervous horse. Remember that exciting a horse like this is self-defeating. Excited horses lose whatever sense they have and in fear will go over, under, or through whatever is attempting to contain them.

It is nearly impossible to rope a horse in a field, and holding on to the horse after it has been successfully roped is also difficult. Dallying the rope off to the bumper of a truck is not an easy maneuver to accomplish, and the roper must be able to stay out of the way of the rope as the horse swings back and forth on the other end. If you must rope a horse, it should only be attempted in a small, sturdy enclosure, such as a wooden round pen. Do not use a round pen made of pipes. This is an invitation to disaster. It is better to leave the horse uncaught than to have to destroy it because it became hung up in pipes and fractured a leg. There are a multitude of trainers that are experienced in this arena, and the owner should be informed of their availability for hire. It is important to keep the horse as quiet as possible and to hide the rope as well as possible. If you are forced into a situation where veterinary care is absolutely necessary in an immediate fashion and the horse must be caught, the following techniques should be remembered. Whirling the rope overhead is not good form because the sound and sight of the rope will frighten most horses. A low, backhand technique is preferable to the cowboy throw. The loop is made so that it brushes the ground when the loop and rope are held at waist level (Figure 7-7). A generous amount of excess rope is played out from the coils, which should be held loosely in the off hand. The loop is held with the dominant hand and carried across the body in preparation for the backhand throw. The position of the roper should be about 3 m from a fence such that when the horse is driven past between the roper and the fence the horse will run into the backhand loop. This technique, although admittedly a last resort, can be extremely successful if all parties involved stay calm.

It should be emphasized that gloves should be worn when attempting to rope any animal. After the loop is over the horse’s head, the coils will come off quickly. If the horse is charging through at such a rate that the rope cannot be held, release it before being jerked off balance and dragged in the dirt. The loose end of the rope can always be picked up from the ground after the horse has stopped running.

Horses that demonstrate signs of dangerous behavior or viciousness should not be given the opportunity to harm veterinary personnel by their physical proximity. There are alternative means of capture, such as tranquilization or anesthesia, that do not require closeness to the horse. Pole syringes, dart guns, and capture guns, although not common in equine practice, can save handlers from serious injury.

CAPTURE AND RESTRAINT OF FOALS

Newborn foals act from instinct in avoiding strange creatures and will hide behind the dam for safety. The capture of foals may be difficult and usually requires two people. Undoubtedly, these foals will not be halter broken, and if they are sick or injured, they do not need the increased stress that accompanies training to halter. The easiest way to capture a suckling foal is to first catch the mare and back her into a corner of a stout wall or solid fence, allowing her foal to come into the corner between the wall and the mare. The barrier should not have any holes that the foal may try to climb through. Flimsy barriers or barbed wire fences should never be used in an attempt to capture foals. The handler of the mare should realize that when the foal starts to struggle against the restraint, it may vocalize in fear and the mare might try to attack those who threaten her foal. The mare handler must be prepared to move the mare to a location away from the foal and handlers immediately following capture of the foal.

The mare should be positioned about the length of the foal away from the corner of the barrier, forming an open box in the corner of the barrier. One person then slowly goes behind the foal, and invariably the foal will cower to the hindquarters of the mare (Figure 7-8). The foal should be approached midway between the head and tail with the knowledge that once it senses hands or arms on it, it will try to escape by bolting, rearing, or kicking. Most commonly the foal will bolt forward into the mare’s hindquarters, and the person should grab under the foal’s neck and at the tail at this time. The tail should be held from underneath with the palm facing up. Grasping the tail is the most secure way to hold the hindquarters, even though the foal may be uncomfortable. It is possible for one person to restrain the foal after this by grabbing the tail and holding it straight up over the back and keeping the other arm under the foal’s neck (Figure 7-9). With bigger foals, two people are necessary for restraint, although the technique is similar. The first person advances toward the hindquarters of the foal as previously described and makes the initial contact with the hindquarters of the foal. The mare is then moved forward slightly, and the second person passes behind the mare and grabs under the foal’s neck (Figure 7-10). Handlers may have to push the foal against a fence until the foal stops struggling. There is a tendency to lift small foals off the ground when accomplishing this task, which is poor form. When the foal loses its footing, it may become more frightened and struggle more vigorously and batter the shins of the handler.

FIGURE 7-8 The mare is backed into a corner, and the foal is driven in beside her to safely capture the foal.

FIGURE 7-9 The handler must move in swiftly from the side of the foal and capture the tail first and sweep the arm under the neck of the foal. The mare handler must move her to a safe location at the same time.

FIGURE 7-10 Two people may be necessary to capture larger foals. The first enters from the rear, and the second comes around behind the mare and grabs the foal under the neck. The foal is then moved toward a solid wall for support.

Attempts to capture foals only by the neck result in a rapid reverse by the foal and subsequent escape. Once a foal escapes, just as with adults, it becomes much harder to capture. Veterinary personnel should not contribute to the negative experiences of a foal. Extra care and gentle techniques should be employed to get the foal to develop trust in people as much as possible.

Following successful capture of the foal, it is usually in the best interest of all to position the mare and foal so that they face each other. They should be as close as possible without the mare becoming a nuisance for the procedure that is performed. It is generally not recommended to separate the mare and foal because they both will fret until rejoined.

HALTER AND LEADS

The halter is the basic restraint tool for horses, and the lead shank should always be attached to the halter. Horses should never be led by the halter alone; a lead should always be attached (Figure 7-11). The halter and rope shank may be inadequate for some tasks. Halters that have rings at the side of the nosepiece may be made more effective if a chain lead is passed from one side to the other. The lead is snapped on the side of the halter that is away from the handler after passing through the loop near the handler, usually on the near side. This arrangement allows finer control of the direction of the horse’s nose and when snapped against the bridge of the nose, it reinforces the authority of the restraint because of the discomfort it causes. The chain lead should come in contact with the horse lightly, if at all, when leading the horse. Only when the horse misbehaves should the chain be used. Constant pressure is worrisome to the animal and does not leave the handler any reserve to use, if necessary.

FIGURE 7-11 Halter and lead rope correctly placed on a horse. Note the position of the handler and the position of the arm. This allows the handler ample opportunity to sense impending movements.

There are three possible positions for the chain lead on the halter. The least authoritative is under the jaw, which causes a squeeze around the nose. Horses with tender chins or those that are not accustomed to a chain lead may throw their head or lunge backward when the lead is pulled. Horses that sense a squeezing of the nose as a signal to back up must be carefully restrained to respond correctly to this type of lead. It is often necessary to release pressure to allow the horse to stop its reverse. The chain over the nose is effective in controlling many horses (Figure 7-12). The top of a horse’s nose is sensitive, and a pull on the lead with the chain across the nose will make the horse drop the nose and stop forward progress. Most stallions should be led with this technique. A variation of this technique is to carry the chain across the nose and then to the cheek piece connection of the halter (Figure 7-13). This gives the handler more control of the horse’s head and nose. The most severe method of chain lead restraint is passing the chain over the upper lip and onto the gums of the upper jaw (Figure 7-14). This method works well with horses that have a bad attitude and need to be reminded about the “chain” of command. When using this technique, it is imperative that the chain is used only when the horse is misbehaving. When used correctly, this method of restraint replaces the use of a twitch and provides the handler with much more stopping power over the horse.

FIGURE 7-12 Lead shank with a chain positioned across the bridge of a stallion's nose to allow for more control.

TYING THE HORSE

A horse should never be tied with a chain over or under the nose. This too is an invitation for disaster. Seldom will it be desirable for a handler to tie a horse to perform a procedure. When a horse must be tied, the equipment must be strong and sound. The halter, rope, and whatever the rope is tied to must be in premier shape. Snaps on a rope are always suspect because all but the heaviest will break when a horse jerks back on them. If something breaks (the rope, halter, or post), the horse will be free and has now learned to pull back as a means of escape whenever tied. Another serious problem that can result from the horse pulling back occurs when it goes over backward and sustains head or neck trauma on landing. A horse should be tied to objects that are at the level of its shoulder or higher to prevent it from pawing and getting a foot over the rope. This also prevents the horse from trying to graze and becoming entangled in the tie rope. Horses should also be tied short; only 60 cm of rope should be present from the halter to the post to prevent the horse from having too much play in the rope and getting in trouble (Figure 7-15). Once a horse is tied, care should be taken to prevent hazardous objects from arriving into the area that might spook the horse, and the horse should never be left unattended. The shorter the horse is tied, the less likely it is to get into trouble.

FIGURE 7-15 Properly tied horse at a rail. Note the level of the tie and the short amount of rope between the post and the halter.

One technique that may be used to restrain (or train) a fitful horse is to place a cotton rope around the mid section of the horse just behind the rib cage and then pull it through between the front legs and through the bottom of the halter. This rope is tied slightly shorter than the halter rope. The basis of this technique is that the horse will hit the cotton rope first and feel the pull against its abdomen, causing it to move forward and release pressure on the rope (Figure 7-16).

FIGURE 7-16 The technique necessary to place a belly rope on a horse that will not stand tied. A, A soft cotton rope is placed around the horse's abdomen and run between the front legs. B, The rope is run down the halter and tied slightly shorter than the halter rope.

For veterinary purposes, it is generally preferable to hold a horse rather than tie it. It is imperative that the holder stand on the same side of the horse as the veterinarian so that the head may be directed toward the practitioner rather than the body or hindquarters (Figure 7-17). If the handler is on the opposite side and the handler bails out, the head of the horse follows the handler, leaving the back end of the horse swinging directly into the veterinarian. When the head is controlled and the horse acts up, the worst that will happen is that the body of the horse will swing away from both handler and veterinarian. No matter what the circumstances, this technique should be upheld because in an emergency situation, self-preservation of the holder will overcome protection of the practitioner.

THE TWITCH

The twitch is a nerve-stimulating device that may immobilize horses and can be helpful in equine restraint. Most twitches are applied to the upper lip of the horse. The most innocuous is the humane twitch, which is a hinged pair of long handles that squeeze down over the sides of the lip and may be secured at the bottom by a thong and snapped back to the halter. The major advantage of this twitch is that once applied it need not be held in place (Figure 7-18). Therefore one person may restrain a horse that is acting up. The disadvantage is that the pressure is fairly mild, and most horses ignore it. More traditional twitches rely on a loop and a leverage device. The loop is either of chain or rope and is placed on the lip and tightened by twisting the leverage device. The leverage may be from a piece of wood or pipe and is about 50 cm long. The loop needs to be seated on the lip behind the heavy gristle pad at the tip and ahead of the nostrils. This area may be hard to find on thick-nosed horses. Horses that have been twitched become quite wise and will throw their heads into the air and tighten their lips when attempts are made to apply the twitch.

The application of the twitch should be done with the calmness and assuredness of the initial capture of the horse. It is best to have an assistant holding the horse by a lead rope when the twitch is applied. The loop should be placed over the thumb and three fingers, leaving the little finger out so that the twitch does not slide down the hand or arm (Figure 7-19). Grasp the end of the horse’s lip, raise the hand with the twitch on it, and slide it onto the horse’s nose. The end of the handle should be held in the opposite hand, in case the horse throws its head. Twist the end of the handle until the twitch is snug and begins to elongate and distort the shape of the horse’s upper lip. The twitch should be tightened until the horse responds by standing still. The average person cannot twist enough to damage the horse’s nose. Once the twitch has been applied, the person holding it should also be holding the lead rope from the halter. He or she should be positioned on the side of the horse next to the shoulder and should be at the end of the handle of the leverage device (Figure 7-20). A number of handlerless twitches are now available for use in minor noxious procedures. These are placed on the horse’s nose in the same fashion as previously described and secured to the halter as shown in Figure 7-21. In the absence of a twitch, it is possible for a person with a firm grip to hold the upper lip in their hand to accomplish a minor procedure. It should be remembered that horses are able to strike out with their front legs, and twitches may evoke this response. Never stand directly in front of the horse when applying or holding a twitch. As mentioned previously, the lip chain may be an alternative that will produce similar results without having to dodge the flying wooden handle of a twitch or the helicopter feet of a horse that has been stimulated to strike.

FIGURE 7-19 The proper placement of the fingers through the loop of chain before placing the twitch on a horse's nose.

FIGURE 7-20 This handler demonstrates the proper positioning while holding the twitch and restraining the horse. Note that the horse is backed into a corner and there is still plenty of overhead space.

FIGURE 7-21 This is an example of a new “handlerless” twitch that may be attached to a horse's nose and secured to the horse's halter, allowing minor noxious procedures to be completed by one person.

A skin twitch may be a more acceptable form of restraint for many owners. This technique may also help for those horses that seem to be “light” on their front feet, attempting to strike when a regular twitch is applied to their nose. Grabbing the skin of the neck just in front of the shoulder and rolling it around the clenched fist will make many horses stand still (Figure 7-22).

FIGURE 7-22 A skin twitch can be a powerful deterrent to an obnoxious horse. The skin just in front of the scapula is drawn into the clenched fist to accomplish this task.

The old cowboy notion of twisting the horse’s ear and biting down on it as a means of restraint is poor practice. The supporting structures of the ear may be damaged, and it is extremely common for the horse to become head shy following ear twisting. Owners are not keen on having this procedure done on their horses, and the handler risks a trip to the dentist after every attempt. Clearly, there are better forms of restraint available.

LIFTING THE FORELEG

Some horses will stand still if a foreleg is picked up and held. The theory is that with one leg in the air, the horse is less likely to leave the ground with the other three. To lift a horse’s foreleg, face the rear and stand next to the horse slightly in front of the leg that is to be lifted (Figure 7-23). Bend from the waist and push your hips slightly into the horse as the hand closest to the horse squeezes the suspensory ligament. The suspensory ligament is immediately palmar to the third metacarpal bone. Squeezing the suspensory ligament will cause the horse to flex its fetlock joint, and cradling the anterior aspect of the fetlock as it flexes will allow the handler to pick up the foot. When holding the foot as a means of restraint, the handler should rotate and face forward with both hands supporting the foreleg (Figure 7-24). To handle the horse’s hoof for procedures, the handler should face the rear of the horse. The foreleg should be placed between the handler’s legs from the rear and held between the thighs just above the knees, freeing both hands to work on the foot (Figure 7-25).

FIGURE 7-23 The proper foot positioning and bending at the waist to pick up a front foot of a horse. The inside hand is placed on the suspensory ligament of the horse's leg.

LIFTING THE HIND LEG

Lifting the hind leg will only be done as part of an examination procedure, not as a means of restraint. To lift the hind leg, the handler stands near the flank area of the horse and bends from the waist with a hand palpating down the horse’s rear limb. A slight lean into the horse will aid in elevating the limb off the ground, and the leg should be pulled upward toward the handler. Then the handler should walk under the limb, staying close to the horse’s body until the leg is outstretched behind the horse with the foot resting on the inside thigh of the handler. The horse’s hock should be at the level of the handler’s waist and the tibial region snugly against the side of the back (Figure 7-26). The leg should stay braced in this position without the use of hands. If the horse should resist, the handler’s arm should clamp down over the horse’s hock joint and attempt to quiet the horse.

FIGURE 7-26 Lifting of the hind limb. A, The handler stands near the flank and palpates down the limb to give the horse knowledge of his presence. B, The leg is brought forward toward the handler before attempting to go out behind the horse. C, The handler walks in underneath the horse's leg, supporting the tibia on his hip and placing the hoof over the inside thigh to support the lower leg.

There are descriptions in the literature of how to tie the horse’s legs up to examine them, but they have many disadvantages to both horse and handler. A horse with a leg tied up may fall and seriously injure itself. There are too many chemical mediators available in equine practice today to recommend rope restraints for lifting limbs.

STOCKS

The use of stocks for fitful horses is clearly the safest way to manage these horses. The best stocks are made of heavy pipes or poles, anchored well to the ground surface, with the horizontal pieces set at the level of the horse’s shoulder (Figure 7-27). Stocks are used for many procedures, such as administration of fluids, dental work, nasogastric intubation, rectal palpations, and injections of jittery horses. Many horses will require some form of encouragement to get into the stocks. This can be done safely with voice commands, a slight raise of the arms by a second handler standing behind the horse, or a straw broom raised and lowered behind the horse. Every effort should be made to keep horses calm as they load into the stocks. Some horses have an innate fear of enclosure. These horses may do anything to get out of a set of stocks. Kicking, jumping, lunging, and striking are all ways in which the horse may try to escape. Therefore it is best to have a quick-release mechanism on the stocks, especially for the rear gate. The rear gate must be closed before tying the horse’s head after loading a horse into the stocks. Once a horse is in the stocks, the same principles apply with regard to positioning of the handler. Do not assume that the horse cannot come over the front of the stocks because many have done so in the middle of a tantrum. Horses should never be left unattended in the stock.

FIGURE 7-27 This horse is about to enter a set of pipe stocks. Note the height of the side pipes, about the level of the horse's shoulder and stifle joints. This stock is well anchored in cement to prevent unsteadiness once the horse is in the stock. The rear end of the horse must always be respected, and the back gate must be closed before securing the head of a horse in the stock. The judicious use of the broom helps get many horses to make the final step into the stock.

The lack of a set of stocks presents a problem with restraint for more noxious veterinary procedures, such as dental work, nasogastric intubation, and rectal palpations. For dental work and nasogastric intubation without stocks, the horse should be backed into the corner of a secure and sturdy area and quieted. Make sure that the ceiling is not so low that if the horse rears it will hit its head. The handler and the veterinarian should be located on the same side of the horse when performing the procedure (Figure 7-28). For palpation without stocks, the horse should be placed along a sturdy solid wall with the handler and veterinarian standing on the same side of the horse. The handler must “read” the horse, and everyone must have a clear idea of where the escape route is located when performing this procedure (Figure 7-29).

TAIL TIE

The horse’s tail may be tied during rectal palpations, vaginal examinations, and minor obstetric procedures. This is accomplished by using a small rope or a roll of gauze tied into the hair of the tail. The tail should never be tied to anything but the horse. Tying the free end around the neck of the horse is best. Should a horse get loose with the tail tied to a stationary object, serious injury could result. The tail tie is a simple quick-release knot using a rope or gauze placed across the tail just below the fleshy portion (Figure 7-30) with the long end tied in a quick-release knot around the neck.

FIGURE 7-30 The steps in making a secure tail tie. A, The rope is placed around the tail. B, The tail is folded back on itself and on the rope. C, The short end of the rope passes over the folded tail, and a loop is pushed through the tail-encircling portion of the rope. D, Tension on the long end of the rope makes the knot snug. Pulling the short end of the rope will release the knot.

HOBBLES

Horses are seldom hobbled or cast (thrown to the ground with the aid of ropes) since the advent of chemical restraint that is both powerful and short acting. Breeding hobbles are still commonly used on farms that have natural breeding operations. These hobbles prevent a mare from kicking effectively. They are fitted around the hocks with web or leather straps that are tied to a neck strap or rope after passing between the forelegs (Figure 7-31).

FIGURE 7-31 This is an example of breeding hobbles placed upon a mare before natural service to prevent her from kicking backward and potentially injuring the stallion.

The scotch hobble is a means of drawing up the hind leg (Figure 7-32). This technique can be used as a form of restraint for the examination of the opposite forelimb. It works by keeping the weight on the hind leg of the side that is examined. Most often the scotch hobble will be used for holding the hind leg that is “up” out of the way during a castration. A heavy cotton rope should be used to prevent rope burn. A loop is placed around the horse’s neck and tied with a bowline knot before the initiation of anesthesia. Once the horse is down in a surgical plane of anesthesia, the rope is passed through the loop behind the pastern area and then brought back to the loop. Pulling the end of the rope using the neck loop as a pulley draws the leg forward. Care must be taken to prevent a rope burn in the pastern area. Some people actually have a leather sheath with two loops on it that is used behind the pastern to allow the rope to slide around the leg without the potential of producing a rope burn.

RESTRAINT OF THE DOWN HORSE

Control of the head is the key to restraining a horse lying in lateral recumbency because to get up the head must be lifted. Kneeling on the neck near the head will keep most horses down. This should always be done from the back of the horse; any activities performed on a horse that is down must be done from the back. An approach from the belly side puts the handler in danger of thrashing legs and feet. To keep the horse from damaging the facial nerve and the down eye, the handler should cushion the lateral area of the face and orbital area. This may be done with a towel, inner tube, or foam mat placed under the head. If such a protection is not available and the horse is thrashing its head, pulling up on the nosepiece of the halter will elevate the nose and prevent the horse from moving the head and producing traumatic wounds to the eye and face.

OTHER HEAD AND MOUTH RESTRAINTS

Horses will sometimes tear at bandages. Devices are available that may be used to prevent this by restricting the horse’s ability to move the head laterally. One such device is the cradle. It is made of wooden slats and leather straps with a buckle that goes over the horse’s neck to secure the cradle and brace the neck in a straight line (Figure 7-33). This device prevents the lateral movement of the neck while allowing the horse to eat and drink. Another method of preventing the horse from chewing at bandages is to tether the horse to an overhead cable in the stall. Running the cable diagonally across the stall is the usual method. With this technique, the horse is able to move about the stall freely, but cannot reach far enough laterally to gain access to the bandage.

Horses with severe pain, with neurologic disease, or undergoing anesthesia will frequently throw their heads, crashing into solid objects and mutilating themselves. To prevent this, there are foam rubber head protectors made to fit snugly over the head of the horse, much like a helmet (Figure 7-34). The use of these and padded stalls help to prevent self-inflicted trauma.

FIGURE 7-34 The handler is placing a protective foam and rubber helmet over the head of this anesthetized horse to protect the head during recovery from anesthesia.

Wire or plastic muzzles are used frequently on horses that are to be held off feed and to prevent them from eating bedding while still allowing them access to water (Figure 7-35).

FIGURE 7-35 This horse is wearing a plastic muzzle to keep it from eating during the perioperative period. The muzzle does have holes to allow the horse access to water.

The examination of a horse’s mouth and dental arcades may be accomplished by standing to the side of the horse’s head and placing the hand of the arm more caudal to the mouth over the bridge of the horse’s nose. The hand nearest the horse’s nose is inserted into the interdental space (Figure 7-36). The hand must be kept in a vertical position. The fingers are placed on the lingual surface of the dental arcade, and the thumb palpates the buccal surface. Following a dental examination, the tongue may be pulled out the side of the mouth through the interdental space. Mouth gags are available to allow for a more complete visual examination of horses’ mouths. A simple wedge (Figure 7-37), which is pushed up between the upper and lower cheek teeth with the handle hanging out, is commonly used. A variation on this is a round gag, used in a similar fashion to the wedge. Caution must be observed with either of the previous gags because horses may fracture their molar teeth with these devices inserted onto their dental arcades. There are also a number of different large-hinged speculums that either fit over the upper and lower incisors or within the dental space and then are suspended from a halter (Figure 7-38). The mouth can then be cranked open, allowing examinations and procedures to be performed on the mouth. Although these devices are effective in getting the mouth open, it should be remembered that they are heavy and cumbersome for both the handler and the horse. The use of any of these speculums is usually coincidental with the sedation of the horse.

FIGURE 7-36 The handler is about to perform an oral and dental examination on this horse. It is critical that the examiner keep the hand in a vertical position while checking the teeth because the horse will bite down on a hand placed in a horizontal plane.

MANUAL AND CHEMICAL RESTRAINT

The manual casting of horses to the ground has been replaced by chemical restraint and anesthesia. Casting always had inherent danger for both horse and handler. Musculoskeletal damage was always possible when the forefeet of the horse were pulled from under it. Once the horse was cast, the thrashing about caused a variety of injuries.

Chemical restraint is now widely accepted and practiced. Many different agents and combinations of agents are used. These are discussed in Chapter 27. Whenever a horse has been sedated, tranquilized, or anesthetized, it is important for veterinary personnel to stay with that horse until it is steady on its feet. When horses are tranquilized, handlers must remember to maintain a safe distance from the horse. When they are under deep sedation, tranquilization, or proceeding through stage 2 of anesthesia, horses may crash into an unwitting handler and cause significant injury to the person. Once the horse is down, make sure of the stage of anesthesia before placing restraint ropes or beginning surgical preparations. A slap to the flank of a horse awaiting castration may save damage from the kick of a partially anesthetized colt.

CAPTURE AND RESTRAINT OF CATTLE

Cattle are less difficult to capture than horses. They are also less discriminating than horses about what or whom they step on or run over. Generally, they are not directly approachable for haltering and leading. However, they are easier to drive into pens, alleyways, and chutes. Herds of cattle will vary in the amount of avoidance present. Some herds will allow a person to approach closely before moving away. It is preferable to have the herd begin to move when the handlers come within about 12 m of the herd. Cattle are herd oriented, so they will crowd and bunch together as they are driven, even climbing over other cows if they are driven too hard or fast. This should be avoided because bruising and other injuries are likely to occur.

It must be stressed that herding cattle into weak barriers must be avoided. Most beef cattle will walk through a barbed or smooth wire fence completely unconcerned and unscathed. Sometimes they even leave the wire in place, although much looser than it was. Calves become adept at slipping through the lower strands of pasture fences.

Cattle are usually less spooky than horses about strange surroundings, but they may balk and then bolt suddenly. Generally the balking occurs just as the cattle reach the open gate of a holding corral after being driven off of a pasture. The clever cattle rancher avoids the placement of strange things at the entrance to a corral, such as dogs, new people, or strange trucks. Veterinary personnel should remain out of sight unless the owner requests assistance in driving cows. Nothing aggravates a rancher more than having all the cows ready to go into the pen and having them spook at the last instant because something or somebody steps into their sight.

Once cattle are in the corral, they are funneled from larger areas into smaller pens and eventually into an alleyway leading to a chute. Usually, there is a system of gates that will allow the handler to block the cattle into these progressively smaller areas. These gates may be used to “cut” calves from cows to facilitate handling. It is best to work larger stock separately from the nursing calves. The handler must be careful in closing gates on a large group of cattle. If they get turned back toward the opening and hit the gate before getting it latched, there is a significant chance of injury to the handler.

The alleys leading to the chute should be built just wide enough for one animal to prevent attempts to turn around (Figure 7-39). People on foot may follow cattle in an alleyway to drive them toward the chute, but they should always be cautious and ready to climb out of the way. Never enter an alleyway that cannot be easily evacuated. The alleyway is usually arranged so that posts or boards may be slipped behind the cattle to prevent them from moving backward. “Tailing” may be used to push a cow ahead in the alley. Tailing is simply grasping the tail in the middle and twisting it forward onto the cow’s back (Figure 7-40). This provides discomfort to the cow, and the usual and expected response is for the animal to move forward. Never underestimate the ability of a cow to get frightened or balk and begin moving backward. This may cause serious injury to the unwise handler. Cattle prods, wiffle paddles, and electric “hot shots” are available and may be used from outside the alley. Many alleyways will have an elevated walkway that allows handlers to move the length of the alley to assist in moving cattle forward to the chute (Figure 7-41). If an alleyway and chute are not available, the next best solution is to run an individual cow into a gated corner. The handler must move quickly to get behind the animal and tail it to keep it from backing up. It may be necessary to rope a cow if no other method of restraint is possible, but this is not a technique that is advantageous or desirable in modern veterinary practice.

FIGURE 7-39 The alleyway that works best for moving cattle is only wide enough for one cow to pass through. Note that the alley is braced well with support posts and there are chains across the top of the alley to prevent it from spreading.

FIGURE 7-40 This is the tail twist method of pushing cattle into a space that they are reluctant to go. Care must be taken to not torque the tail so much as to cause a fracture of the coccygeal vertebrae.

FIGURE 7-41 A “hot shot” with the proper positioning of the handler shown. These devices work well, but must be used judiciously to facilitate easy movement of cattle. The walkway that allows for human traffic above the cattle and outside the alleyway is evident just in front of the handler.

Once the animal has stopped moving, it is then possible to halter it and restrain it by the head. A single, calm cow restrained in a stall may be haltered without resorting to a chute. A bovine halter is all one piece and made from rope, as opposed to the equine halter. The halter is placed by loosening the nose loop first and then flipping the crown loop over the animal’s ears. Once the crown loop is in place, the nose loop may be positioned and the slack in the free end of the rope taken up as the rope comes under the jaw (Figure 7-42). Always keep the cow’s head at arm’s length and bend forward from the waist because an animal that becomes nervous will throw its head and may catch the handler in a compromised position. Animals with horns may be restrained by placing a loop of rope around the base of both horns and then dallying off to a solid post.

FIGURE 7-42 A rope halter placed correctly and tied to the pipe at an appropriate level to restrain this Angus heifer.

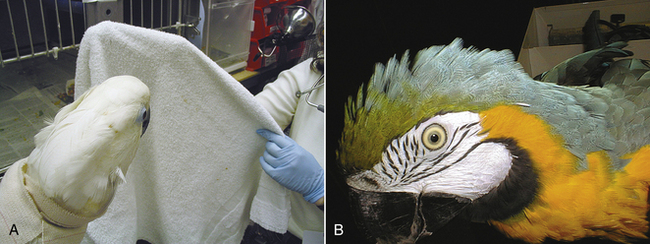

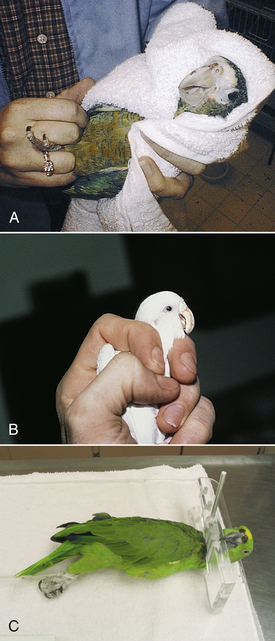

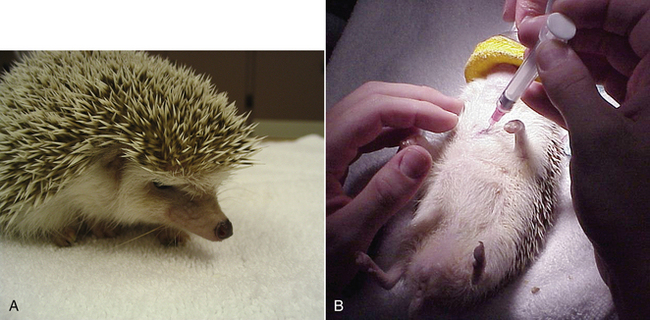

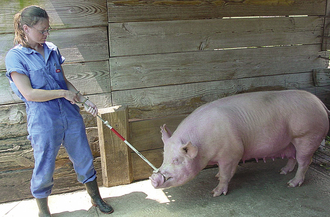

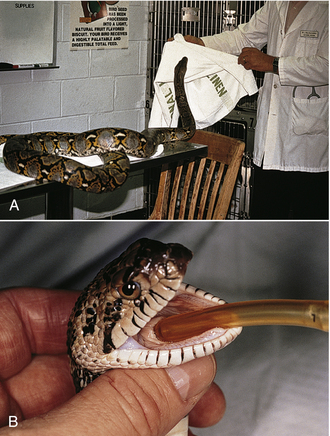

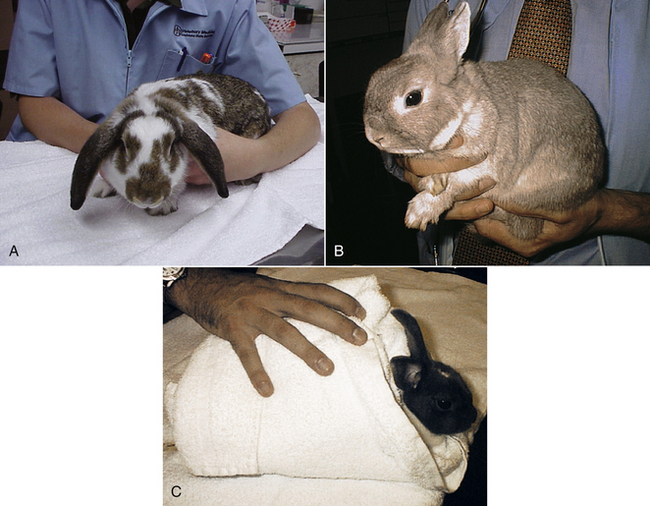

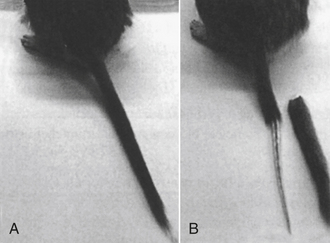

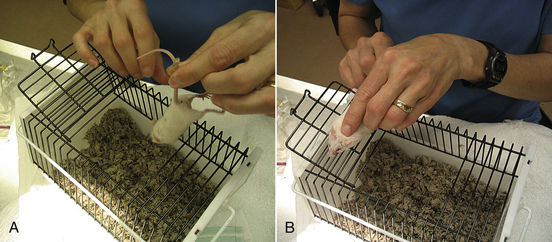

Calves are captured in much the same manner as foals. If the calf is small enough, it may be “flanked” and placed in lateral recumbency (Figure 7-43). The dam of the calf deserves respect and must be observed for aggression.