Animal Behavior

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

1 Define behavior wellness and explain the importance of behavior wellness programs in pet animal practice.

2 Differentiate between positive reinforcement, positive punishment, negative reinforcement, and negative punishment.

3 Describe aspects of social behavior and social hierarchies in dogs and cats.

4 List criteria that define behavioral health in dogs and cats.

5 Define socialization and identify critical periods of social development in dogs and cats.

6 List and describe the five steps in the Five-Step Positive Proaction Plan.

7 List the five major areas of a behavioral assessment.

8 List the most common agnostic behaviors exhibited by animals.

9 Describe methods for dealing with threatening and aggressive animals.

10 List and describe common products used for behavior modification in dogs and cats and handling aggressive animals.

WHY BEHAVIOR WELLNESS?

Many owners who relinquish their pets have tolerated problems for months or years, often unable to find effective help (DiGiacomo et al, 1998). Owners often ignore or tolerate problems, such as inappropriate elimination, phobias, or family pets not getting along, until the problem worsens or there is a lifestyle change that makes resolution of the problem a priority. For example, a couple might tolerate a pet’s occasional or frequent house soiling until they learn that they are expecting a baby. Concern about the baby crawling on the soiled carpet in the future threatens the pet’s continued presence in the home. Problems are usually much more difficult to resolve under these conditions—a long-standing problem and owners unrealistically demanding a quick solution—than if intervention had been obtained earlier.

In many cases, a window of opportunity for the prevention and detection of problems and for providing timely intervention exists, but owners and veterinary care providers are not taking full advantage of it. In the general practice of veterinary medicine, a pet’s behavior is most often attended to during puppyhood and kittenhood, if the animal’s behavior presents a problem at the veterinary hospital, and when the owner mentions a problem. Making behavior wellness care an integral part of the delivery of pet health care services is more beneficial than a narrow focus on problem resolution, which is often sought at a crisis moment, as in the earlier example.

WHAT IS BEHAVIOR WELLNESS?

Behavior wellness is the condition or state of normal and acceptable pets’ conduct that enhances the human-animal bond and the pet’s quality of life (Hetts, Heinke, Estep, 2004).

Behavior wellness care is the planned attention to a pet’s conduct and the active integration of behavior wellness programs into the delivery of pet-related services, including routine veterinary medical supervision. Ten components to behavior wellness care have been suggested (Hetts, Heinke, Estep, 2004) and are listed in Box 11-1.

Behavior wellness programs are protocols, procedures, services, and systems that educate pet owners and professionals about what constitutes the behaviorally healthy or well pet; promote behavioral wellness through positive proaction, behavior assessments, early intervention, and timely referrals; and decrease unrealistic human expectations and interpretations of a pet’s behavior.

TECHNICIANS CAN PLAY A STRATEGIC ROLE IN BEHAVIOR WELLNESS CARE

When given sufficient education in behavior and behavior wellness care, including direction and support from the veterinarian, veterinary technicians can be the most strategically positioned individuals on the veterinary health care team to deliver many behavior wellness services.

The technician is often the first person owners ask about why their pets behave the way they do, how to prevent problems, and what to do once their pets’ behavior has become a problem. Technicians are usually best positioned to have the first contact with clients during scheduled appointments. With the support of the veterinarian, technicians can use these opportunities to deliver the appropriate elements of behavior wellness care. Elements of behavior wellness care are listed in Box 11-1.

Practice management consultants are emphasizing the importance of veterinarians delegating health care tasks to their support staff when such tasks do not require the veterinarian (Wood, 1997). The increased use of technicians in history taking, nutrition, prophylactic dental services, and general clients’ education has set precedents that provide the veterinary technician with an opportunity to play a leading role in the delivery of behavior wellness care. Doing so is beneficial to the technician, the practice, and to pets and their owners (Box 11-2).

The advantages of providing behavior wellness care can extend beyond even these beneficiaries to communities and society at large. A decrease in dog bites could be seen if more veterinary hospitals:

1. Offered puppy socialization classes or routinely encouraged and referred puppy owners to them while puppies are still in the sensitive socialization period between 4 to 12 weeks of age.

2. More often used nonconfrontational handling and restraint techniques so as not to contribute to defensive aggressive behavior.

3. Discouraged the use of dangerous and harmful procedures, such as scruff shakes and “alpha rolls.”

4. Provided behaviorally sound advice about how to help dogs fit into the social fabric of the family to counter the likening of families to wolf packs, as is common in popular media.

BEHAVIOR EDUCATION FOR TECHNICIANS

Technicians who deliver behavior wellness care must give up-to-date, scientifically accurate information. Scientific knowledge must replace nonscientific interpretations of behavior and information based solely on personal experience and beliefs.

Historically, most of the emphasis on continuing veterinary education in animal behavior has been on problem resolution. Lectures on resolving separation anxiety, aggression problems in both dogs and cats, and fears and phobias are common in veterinary technicians’ continuing education programs. Time spent on these topics has often come at the expense of basic education in behavior.

As in other aspects of veterinary technicians’ education, foundational skills must be acquired first. Whether within the veterinary technician’s curriculum or through continuing education, technicians must become familiar with basic concepts in applied ethology and animal learning. The former should include knowledge of species-specific communication signals and body postures, and the latter must include principles of operant and classical conditioning.

Continuing education opportunities focused on implementation of behavior wellness services, including implementing puppy classes in the veterinary practice, are now available∗†‡§ (Hetts and Estep, 1999). Technicians can also consider continuing education opportunities other than or in addition to those traditionally provided within the field. National humane organizations, animal-control associations, and dog-training associations conduct training conferences that would be beneficial to technicians delivering behavior wellness services. For example, the Association of Pet Dog Trainers 2007 Annual Conference included presentations on puppy classes and training, dog bites, shelter dogs, critical thinking and understanding the difference between true, junk, and pseudoscience, and one by a veterinarian on balancing disease prevention and a puppy’s socialization.

Resolving behavior problems requires the most advanced and complex skill set, which in turn requires the most education and experience to acquire. Technicians should first build a solid education in the sciences of ethology and animal learning and have experience with other aspects of behavior wellness care before participating in problem-resolution activities.

A CHANGE IN PERSPECTIVE

Providing behavior wellness care requires that the technician not only react to questions when they are asked, but also take a proactive approach and make behavior a part of every nonemergency appointment. This means initiating discussions about the pet’s behavior, whether the owner does or not.

Veterinary technicians who do not take the lead in asking questions about behavior are missing the point of behavior wellness. As will be seen throughout this chapter, pet owners do not know what they do not know and are therefore unlikely to initiate discussions about behavior until a problem exists. This guarantees that opportunities for the promotion of good behavior and early detection of problems that are at the core of behavior wellness will be missed.

Providing behavior wellness is another example of providing preventive care. Just as vaccinations prevent contagious diseases and specific medications prevent parasite infestations, behavior wellness programs can prevent behavior problems and promote healthy behaviors.

BEFORE IMPLEMENTING BEHAVIOR WELLNESS CARE

Before offering any kind of behavioral information, technicians should clarify their role with the practice owner or their designated supervisor. Veterinarians usually determine what medical information or advice they wish technicians to impart to clients, and the same procedure should be followed when it comes to behavior.

When technicians’ roles are not clearly defined, they may feel pressured and resentful of the time spent answering behavioral questions because this prevents them from completing other assigned tasks. On the other hand, if technicians spend significant time on behavior issues that is not charged to the client, this sets a dangerous precedent for the practice. It is one of the reasons that veterinarians believe, often erroneously, that providing behavior services is not financially feasible.

Behavior services should be professionally delivered so that their value is fully recognized and they benefit not only clients and their pets, but also the practice. The Society of Veterinary Behavior Technicians promotes and encourages the training of technicians in behavior and their appropriate involvement in the delivery of behavior services, making this organization an invaluable resource (Price, 2001). Information about the society can be found at the website listed in Box 11-3.

REQUISITE KNOWLEDGE

Any technician who wants to advise clients about promoting healthy behaviors or changing unwanted behavior patterns must have at least a rudimentary understanding of some aspects of learning theory and must be familiar with the ethology of the species they work with, including species-typical behavior patterns. In-depth coverage of these topics is beyond the scope of this chapter. However, to help technicians better understand and more effectively use the Five-Step Positive Proaction Plan discussed later in this chapter and to compensate for the dangerous misinformation regarding “dominance” and social hierarchies in both dogs and cats, an overview of these topics will be provided. Technicians are referred to the Further Readings Section at the end of this chapter for more information.

An Overview of Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning is only one type of learning that is important in behavior modification. Operant conditioning is based on the fact that the consequences of a behavior will influence its frequency. Behavior that is rewarded will increase in frequency, whereas behavior that causes unpleasantness to the animal will decrease. Technicians must not forget that rewards and punishments can be both external and internal to the animal and not always under the control of a trainer or handler.

Operant conditioning allows for four behavioral consequences, which are diagrammed in Table 11-1. To better understand these consequences, technicians must remember to think of “positive” and “negative” in the mathematic sense of adding and subtracting. Remember that by definition reinforcement increases behavior and punishment decreases it, regardless of whether each is positive or negative.

TABLE 11-1

Behavioral Consequences in Operant Conditioning

| Type of Event or Stimulus | Add or Give | Take Away, Subtract, or Avoid |

| Something pleasant | Positive reinforcement | Negative punishment |

| Something unpleasant | Positive punishment | Negative reinforcement |

Thus positive reinforcement increases behavior because something pleasant is added following a behavior. Positive punishment decreases behavior because something unpleasant is added following a behavior.

Negative punishment decreases behavior because something pleasant is taken away (subtracted) following a behavior. Negative reinforcement increases behavior because something unpleasant is taken away or avoided (subtracted) following a behavior. Box 11-4 gives examples of each of these consequences.

An Overview of Social Behavior and Social Hierarchies in Dogs

For many years, in the popular literature and to some degree the professional literature, the dog’s relationship to its human family has been likened to the social structure within a wolf pack. There are many problems with this model including misconceptions about a wolf’s social behavior and that it does not take into account significant differences in behavior between wolves and dogs. A few of these differences are listed in Box 11-5.

Technicians will often encounter dog owners who say they have a “dominant dog,” and this fact is the source of the dog’s problems. This comment is incorrect in many respects, one of which is that it mistakenly implies that “dominance” is a personality trait, rather than the role a dog assumes in a relationship. A dog may assume a dominant role in a relationship with one individual and a subordinate role in another. Roles may change over time, based on who the social partners are and the context in which the interaction or conflict occurs.

For example, a dog may give up his resting place on his favorite chair when dog A or person A asks him to, but not when person B does. If dog B is clearly in a subordinate role with the dog on the chair, dog B will not even ask.

The function of social hierarchies is to prevent conflicts over resources from occurring in a social group. Many behaviors that have been attributed to “dominance problems” have nothing to do with resource allocation and roles and relationships. Examples of these are given in Box 11-6. Dog owners are often instructed to withhold certain privileges (such as sleeping on the bed) and to establish strict rules (never step over your dog, make your dog move out of your way) to establish their “dominance” over their dogs. The fallacies with these recommendations are that most dogs do not view these interactions as competitions, and they confuse “dominance” with obedience.

A dog owner may have little control over her dog (the dog does not respond to “commands,” jumps on people, dashes through the door in front of her, pulls on the leash, barks at the door, even growls at visitors), but still be in a dominant role with her dog (she can easily take food and other items away from the dog, move the dog from the bed or furniture, pet and groom the dog, etc.).

Many dogs are mislabeled as “dominant” when they actually are quite fearful. This was the case with 9-month-old Zeke, a neutered male vizsla that was growling at his male owner when he tried to move him off the bed. Rather than using positive reinforcement techniques to teach the dog to get off the bed, the owner had been grabbing for the dog’s collar and yanking him off the bed. The dog’s body postures while growling were clearly fearful—ears back, head lowered, and eyes dilated—as he sought to defend himself from being manhandled. The confrontation was not about getting off the bed, but one of self-defense.

Similar problems can develop when owners use “scruff shakes,” and “alpha rolls” (throwing and pinning their dogs to the floor) to “discipline” their dogs. Technicians should avoid recommending these procedures and counsel dog owners about these dangers. These techniques do not mimic a dog’s or wolf’s behavior. Although a dog may voluntarily roll on its back in response to a social challenge from a dog in a more dominant role, physically pinning a dog to the ground involves force and is more similar to what occurs in a dog fight than what happens in a ritualized social communicative display.

Technicians are encouraged to learn more about canine ethology by reading items from the Recommended Resources list, especially those by McConnell, Serpell (editor), and Coppinger.

Important Aspects of Social Behavior and Social Hierarchies in Cats

A mythology about cats wanting to be “dominant” over people has not developed the way it has in reference to dog-human relationships. The “don’t pet me anymore” behavior of cats is the one most common problem attributed to a cat’s attempt to “dominant” a person. In this behavior, the cat after permitting petting for a period of time will suddenly turn and bite or attempt to bite the person petting him. More commonly seen in males than females, this behavior is poorly understood, and there has been no observational research to support attributing this behavior to the order of the social hierarchy between a cat and a person.

Both the social behavior and domestication history of cats is quite different than that of dogs, resulting in significant differences in cats’ social behaviors toward people as compared with those of dogs. Cat behavior scientists have speculated that the cat-person relationship is more analogous to kitten-mother, rather than peer to peer (conspecific), as is true for dogs and people (Bradshaw, 1992).

Cats’ social hierarchies appear to be even more fluid than those of dogs. In a study of in-home pet cats, resource allocation was often time dependent rather than one individual always having priority access when in competition with another. For example, cat A might have priority access to the best window perch in the morning, but cat B would have priority in the afternoon (Bernstein and Strack, 1996). In studies of free-ranging cats, males were more likely to leave and avoid a confrontation the closer they were to the opponent’s territory.

Cats do not seem to guard resources in the same way as dogs yet through subtle communication may be able to exclude other household cats from food dishes, litter boxes, and other necessities. Cats do not have ritualized play invitations or submissive behaviors in their social behavioral repertoire, so play “fights” can more easily escalate into real conflicts. Because many aggression problems between family cats are motivated by territoriality and defensiveness, many can be prevented through proper introductions. This is why it is so important for technicians to create wellness plans for new pet introductions, as explained later in the chapter.

Technicians are unlikely to find cats attempting to “dominate” them in the veterinary practice. The most common reason for a cat’s aggression toward people in this setting is fear and defensiveness. Cats do not “scruff” other cats to assume and maintain social superiority, so this restraint technique does not mimic cats’ behavior anymore than scruffing and pinning mimics dogs’ behavior.

Technicians are encouraged to expand their knowledge of cats’ behavior by reading several of the scientific books on cats’ behavior contained in the Recommended Resources list at the end of this chapter. Technicians who will be working with horses and birds should also make use of the suggested readings about the social behavior of these species.

COMPONENTS OF A BEHAVIOR WELLNESS PROGRAM

DEFINING BEHAVIORALLY HEALTHY PETS

Technicians are taught how to recognize healthy animals according to certain criteria. These commonly include good condition of the skin and coat, clear eyes, a lack of external and internal parasites, proper weight, clean teeth, healthy gums, etc.

Criteria for behavioral health are often not considered. Behavioral health is more than the absence of behavior problems. As defined previously, it is the presence of normal and acceptable pets’ conduct that enhances the human-animal bond and the pet’s quality of life (Hetts, Heinke, Estep, 2004).

Specifying the criteria for normal and acceptable pets’ conduct allows technicians to help pet owners set goals for promoting desirable behaviors, rather than just reacting when problems arise. Suggested criteria for behaviorally healthy cats and dogs are listed in Box 11-7. Technicians can use these as a basis for discussion with veterinarians and other co-workers to establish criteria within their hospitals. Criteria for other species can and should be established. The assessment of behavioral health by using these and other criteria is another component of behavior wellness care that will subsequently be discussed.

ESTABLISHING REALISTIC EXPECTATIONS AND HELPFUL ATTITUDES

Anthropomorphic explanations for and unrealistic expectations about pets’ behavior contribute to relationship problems between owners and pets. Technicians can play a vital role in educating clients in these areas.

Realistic Expectations

Technicians can routinely tell new pet owners to expect to lose something of value simply because they share their lives and their homes with an animal. To put it in terms pet owners will understand, clients will lose something of monetary or sentimental value (or both) when their pets chew up, tear up, eat, track mud on, shed on, relieve themselves on, and vomit or have diarrhea on their possessions. Most people expect some problem behaviors from puppies and kittens, but surprisingly many owners do not expect their 8- or 9-month-old cat or dog to still be prone to chewing and destructive play behaviors. Even well-behaved pets will inadvertently engage in behaviors that cause damage.

Clients who have recently acquired adult animals often make the erroneous assumption that their new pets are already “trained,” and they will not have to worry about house training or chewing and other destructive behaviors. Adult animals new to the home, however, should be treated just like puppies or kittens for the first few weeks to prevent problems as a result of owners’ expectations that are too high; adult pets often need training and supervision while they are making the adjustment to their new homes.

Reinterpreting Anthropomorphic Interpretations

Technicians can also help clients understand that their pets’ behavior is not motivated by spite, revenge, rebelliousness, jealousy, or guilt. When owners realize that their pets are not vindictive or mean spirited, do not have a moral sense of right and wrong, or misbehave even though they “know better,” they are usually more willing to work with their pets’ behavior and to listen to possible solutions.

Technicians can tell people that animals do what works for them—to meet a need, cope with stress, or control their environment. Destructive behavior that occurs when a pet is left alone, for example, is not motivated by revenge. Alternative explanations are separation anxiety, playful behavior, or the pet’s realization that unpleasant consequences do not occur in the owner’s absence.

Technicians often have the opportunity to correct pet owners’ misinterpretations that their pets “know better” and look “guilty” when evidence of their misbehavior is discovered. “Guilty looks” are submissive behaviors, such as the avoidance of eye contact, crouched body posture, flattening of the ears, and lowering of the tail when threatened by their owners. When owners discover evidence of misbehavior, they display behaviors, such as yelling, pointing fingers, and staring, that pets find intimidating and that in turn trigger submissive behaviors that are misinterpreted as guilt.

Other examples of how technicians can clarify misinterpretations can be found in Box 11-8.

PROVIDING PET-SELECTION INFORMATION

The most proactive behavior wellness service is the education of clients about pet selection. Unfortunately, few clients seek this service from the veterinary practice. Technicians can play a helpful role by regularly asking clients whether they are considering adding a new pet to the family and reminding them that the veterinary practice can assist them in selecting a pet that will best meet their expectations.

A closely related subject is helping owners introduce pets to one another. Better relationships between family pets could be created if introductions were better managed. Pet owners do not usually ask for help until relationship problems between pets have already begun so creating opportunities for early intervention will be up to the veterinary professional. How the new pet is getting along with resident pets should be a standard question put to clients when the newly acquired pet is brought in for its first veterinary appointment. A plan for introducing pets to one another that follows the Five-Step Plan for Positive Proaction (Hetts, Heinke, Estep, 2004), which will subsequently be discussed, should also be given to clients (see Box 11-14).

IMPORTANCE OF SOCIALIZATION

Most species of social animals have a sensitive period during which socialization to their own species, to humans, and to other animals occurs most easily. Socialization refers to the process by which an animal develops appropriate social behaviors toward members of its own and other species (Bateson, 1979). In dogs, this period is from 4 to 12 weeks of age (Scott and Fuller, 1965); in cats, it is from 3 to 7 weeks of age (Karsh and Turner, 1988); and in horses, it begins at birth (Waring 2003). There may also be sensitive periods for the acclimatization of animals to new places, situations, and things, which occur around the same ages; but the precise time of these is unknown.

The process of socialization requires providing the young animal pleasant experiences with people, situations, inanimate elements of the environment, and other animals. Adequate socialization helps the animal to adapt to change and not react with fear or aggression to common, everyday events.

Technicians should educate pet owners about how early socialization can prevent the development of many behavior problems, especially those caused by fearful behavior. Cats are typically undersocialized, as evidenced by the tendency of many to hide when visitors come, be afraid in unfamiliar environments, and not enjoy human handling.

A practical approach to socialization advice is that during its sensitive period, a young animal should be exposed to elements of its world that are relevant to its adult role. A foal should have positive experiences with the horse trailer, kittens should be introduced to friendly dogs, and puppies should interact with friendly, well-behaved children.

Veterinarians have historically been reluctant to recommend early socialization programs for kittens and puppies because of concern about disease transmission. If recent outbreaks of contagious disease have been rare in the local area and the percentage of vaccinated animals is high, early socialization may present little hazard.

Although the veterinarian will set practice policy regarding early socialization programs, as one prominent veterinary behaviorist wrote “… the risk of a dog dying because of infection with distemper or parvo disease is far less than the much higher risk of a dog dying (euthanasia) because of a behavior problem” (Anderson et al, 1999) that could have been prevented through early socialization and training. One finding from a study of puppies adopted from humane societies found that puppies were more likely to remain in their homes if their owners had attended puppy socialization classes with their puppies (Duxbury et al, 2003).

With proper training and the support of the veterinary practice, technicians can offer puppy and kitten socialization classes. This limits concern over disease transmission if all attendees are immunized patients of the veterinary practice. Resources to help technicians work with veterinarians to offer classes are available (e.g., Hetts and Estep, in prep, Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman 2003).

FIVE-STEP POSITIVE PROACTION PLAN

The topic of preventing behavior problems is not a new one for technicians. However, a behavior wellness view focuses on promoting desirable behaviors, not just preventing problems.

This Five-Step Positive Proaction Plan (Hetts, Heinke, Estep, 2004) organizes information and provides a framework that technicians can use when they talk with pet owners about how they can create behavior patterns that define a behaviorally healthy pet. Having a means to organize information makes it easier to develop practical educational handouts about promoting healthy behaviors. The best time to at least introduce elements of this plan is the first veterinary visit or series of puppy and kitten visits after a new pet has been acquired. The plan can also be used during future appointments as a partial response to behavior concerns as they are discovered through behavior assessments and observations of the pet. The five steps in the plan follow, in client-friendly terms, with more technical phrases and terms in parentheses:

1. Catch your pet doing something right. (Elicit and reinforce appropriate behavior.)

2. Do not let bad habits develop. (Prevent or minimize inappropriate behavior.)

3. Meet your pet’s behavioral and developmental needs.

4. Use the “take-away” method (negative punishment) to discourage inappropriate behavior.

5. Minimize “discipline” (positive punishment) and use it correctly when necessary.

Each of these steps will be discussed in some detail.

Step One: Elicit and Reinforce Appropriate Behavior

This step is all about encouraging clients to more often positively reinforce their pets for good behavior and assisting them in finding ways to elicit good behavior that they can reward. Clients need specific instructions about how to proactively get their pet to do what they want, rather than reacting to unwanted behavior. For example, technicians can tell owners to have treats at the door for occasions when people are greeted and to encourage the dog to sit, rather than yelling and pushing the dog off when he jumps up (Figure 11-1).

In some situations eliciting good behavior is integrally connected to meeting the pet’s behavioral needs, another step in the proactive plan. For example, establishing reliable litter-box behavior is primarily dependent on creating a litter box that meets the cat’s behavioral preferences.

Technicians should also instruct owners to reward their pets when they catch them doing something right. It is easy to forget that behaviors that are rewarded are likely to be repeated. This is a powerful behavior modification method to which owners seldom devote enough effort. It is about providing animals sufficient feedback about their behaviors. Most pets are more likely to receive feedback when they misbehave, rather than when they are behaving appropriately.

Whenever the dog eliminates outside, the cat plays with its own toys, the foal nuzzles rather than nips at your hand, the puppy is lying down quietly, or the kitten is resting on a chair because owners expect these good behaviors, they are less likely to provide the animal feedback about them. Instead, good behavior is often passively accepted or ignored when owners should actively reinforce the behaviors they desire.

Reinforcement may consist of a tidbit, presentation of a new or favorite toy, petting, or any other event that the pet finds rewarding. Praise alone, especially when an owner is first establishing a relationship with a new pet, is often not adequate reinforcement. Praise usually first needs to be paired with petting, play, or food for a time to become sufficiently reinforcing.

Technicians may need to educate owners about the value of using food in training. Both food and toys are powerful ways to elicit and reinforce behavior when used correctly. The owner controls access to both, so the old adage that “a dog should work for me, not for food” is a useless argument. Pet owners may also resist the use of food to aid in establishing good behavior because they may believe this results in “he’ll only do it when he knows I’ve got a treat.” Although this can happen, it is due to training errors, rather than an inherent problem with using food. To overcome these errors suggest the following:

• Rather than using the food as a lure to elicit the behavior (the pet sees the food before performing the behavior), the pet must not see it until after the behavior has been performed (the food is used only to reward the behavior).

• Until the behavior is well established, the food should be used to reinforce every occurrence of the correct behavior. Once the pet is responding well, the food should be given on an intermittent schedule (e.g., for some correct responses but not others) on an unpredictable basis (petting or praise should always be used). Intermittent reinforcement maintains correct responding better than continuous reinforcement.

• Because the pet must not know when food will be used to reward behavior and when it will not, all cues (e.g., a treat pouch, sound of food being removed from a container before behavior is performed, etc.) that the pet can use to predict whether food is available must be eliminated.

Certified Professional Dog Trainers (CPDT) should easily be able to help clients understand these procedures. Their website is listed in Box 11-3.

Step Two: Prevent or Minimize Inappropriate Behavior

When pets do not have the chance to make “mistakes,” it is much easier to create good behaviors. The fewer opportunities an animal has to repeat or “practice” undesirable behaviors, the less likely such behaviors will become habits.

A cat that begins to eliminate on the carpet because the litter box does not meet its behavioral needs may quickly develop a surface preference for carpet. If a puppy gets used to pulling on the leash while walking, this can quickly become a habit, making loose leash walking more difficult to teach. Playing with a kitten with hands and feet rather than its toys can result in a cat that bites hands and considers human body parts to be playthings.

The technician should instruct owners that they must manage the pet’s environment to prevent unwanted behaviors from occurring and developing into habits. Constant supervision of young animals and pets new to the household is an absolutely critical component of house training and also of teaching puppies and kittens to chew and scratch their own toys rather than household items.

Supervision can be accomplished in a number of ways, including crate training, use of baby gates to keep the pup in either a puppy-proof area or in the same room with the owner (Figure 11-2), or tethering the dog with a leash and collar to the owner or an object near the owner. Supervision of cats and kittens may mean closing doors to certain parts of the house.

FIGURE 11-2 Environmental management with a baby gate to prevent opportunities for unwanted behavior.

Crate Training: A crate can be an extremely useful method of supervision, especially for puppies. Dog owners too often misuse or overuse crates because they are not given good information about their use. Technicians can play a vital role by giving dog owners accurate and complete information about crating to counteract the misinformation clients are likely to come across through other means, such as the Internet and television programs.

In the popular literature, crates are portrayed as analogous to dens. As the comparison points in Box 11-9 show, they are not. If technicians recommend crate training to pet owners, they should also cover the following topics:

Correct size of crate: Dogs need to be comfortable in their crates. This means sufficient room to stand up to full height, easily turn completely around, and lay down on a side, fully relaxed. Some dog-training books recommend crate sizes for pet dogs that provide less space than required by the Animal Welfare Act for dogs in research facilities.

If the dog soils in the crate, it is not appropriate to recommend a smaller crate. Soiling the crate does not mean it is too large; it means something is wrong. The dog may be confined in the crate for longer than he or she can control himself, he or she may be anxious and frightened, or he or she may even have a medical problem. The technician and the veterinarian should help the owner decipher why the dog is soiling, whether this means a medical work-up and/or a behavior consultation.

How to acclimate the dog to the crate: Dogs do not automatically like being confined in crates. They must be introduced to them gradually by following steps similar to those listed in Box 11-10. This acclimation process may require just a day or two or as long as several weeks with dogs who have previously been anxious when crated.

How to acclimate the dog to being left alone in the crate: This step is frequently overlooked. Just because the dog is comfortable in the crate when someone is home does not mean he will be when left alone. Technicians need to educate owners about the importance of gradually acclimating the dog to being crated when alone. The first absence, for example, may need to be a maximum of 15 minutes. If the owner has any concern about how the dog is tolerating the crate when left alone, the technician can suggest that the client videotape or audiotape the dog.

How and when to make the transition to leaving the dog alone, free in the house: Crates should be a short-term management tool, not a way of life. The goal is for the dog to be unconfined in the home (perhaps with access to a backyard) when left alone. One study (Patronek et al, 1996) revealed that dogs that spent most of their day crated were at an increased risk for relinquishment. The explanation for this finding might be that crating merely manages a problem, such as house soiling or destructiveness. The continued existence of the behavior problem puts the dog at risk for surrender when management, for whatever reason, is no longer possible or effective.

Warning signs that a dog is not adjusting well to the crate: An important related subject that should be discussed is guidelines for when a crate should not be used, such as when separation anxiety problems exist or when the dog becomes panicked when it is confined (Box 11-11).

Step Three: Meet the Pet’s Behavioral and Developmental Needs

Animals do things to get their needs met. Technicians can teach owners how to meet their pets’ needs in ways that encourage and provide for desirable behaviors. This is much more effective than owners vainly trying to suppress normal behaviors, such as chewing, playing, or elimination. Instead, these behaviors should be directed onto appropriate targets, or steps should be taken to help the behaviors occur at appropriate times or locations.

Defining a list of widely accepted behavioral needs for pets, although difficult and controversial, has been proposed (Hetts, Heinke, Estep, 2004) and can be found in Box 11-12. This list presupposes that an animal’s basic survival needs for food, water, and shelter have been addressed.

An Example of Meeting the Pet’s Elimination Needs: Technicians can educate cat owners about cats’ behavioral needs regarding a litter box based on the list in Box 11-13. Many litter-box problems develop because the areas the cat is soiling meet the cat’s behavioral preferences for elimination better than the litter-box area.

Figure 11-3, for example, shows a litter box that is unacceptable in several ways, as follows:

FIGURE 11-3 A litter box that will not meet the behavioral needs of most cats. See text for reasons.

• In an area, such as an unfinished basement, where the cat is unlikely to spend much time

• Not easily accessible, such as a closet that has little space or the door to which can easily close unexpectedly

Compare it with a clean litter box (Figure 11-4) located in a quiet, accessible, but private area. It is clear which box better meets the cat’s behavioral needs and is therefore more likely to be used.

An Example of Meeting the Pet’s Play Needs: Owners who do not realize that they must be prepared to devote time to playing with their pets may become frustrated with their pet’s “hyperactivity” or pestering behavior that results when this need is not met. Other behavior problems that can result from a lack of physical activity and mental stimulation include self-injurious behaviors, destructive behaviors, excessive vocalizations, difficulties in basic training, and ignoring directions from the owner.

Pets need time for social play with their owners or other animals and for object play with toys. A variety of toys that allow for chewing, chasing, stalking (cats), and retrieving (dogs) should be provided.

Determine Individual Preferences: Technicians can explain to owners that sometimes it may be necessary to create choice situations so that they can determine their pet’s preferences relative to various behavioral needs.

For example, cats need objects to scratch, but individual differences exist for what they prefer. Most cats tend to prefer a scratching post that is oriented vertically (Figure 11-5), although some prefer a horizontal scratching area (Figure 11-6). An owner can discover the specific preferences of a cat by giving the cat choices among vertical and horizontal scratching posts presented at the same time in the same location and then noting which one is most used. Similar choice “tests” can be used to determine what individual animals prefer in the way of toys, bedding, litter boxes, and surfaces for elimination. See Table 11-2 for examples of preferences that could be subjected to testing.

Step Four: Use the “Take-Away” Method (Negative Punishment) to Discourage Inappropriate Behavior

Parents may be familiar with the concept, but rarely think to use it with animals. As a reminder, the “take-away” method refers to negative punishment (see Box 11-4 and Table 11-1). To stop an unwanted behavior, technicians can tell owners how to take away something the animal wants. This is similar to taking away a child’s television privileges as a consequence of bad grades.

If a puppy is playing too rough, rather than yelling, pushing, or slapping the pup, the owner can walk away and ignore the puppy. The puppy learns that rough play loses him his chance to play at all.

If a horse becomes “pushy” when the handler enters the stall with grain, the handler does not feed the grain to the horse and leaves the stall.

If a cat is meowing for attention, the owner can shut herself in another room for 5 or 10 minutes and not allow the cat to join her.

Negative punishment does not involve the application of aversive stimuli, so it is often preferred over what pet owners generally think of as “discipline” (yelling, hitting, pulling on the collar, squirting the pet with water, scruffing, or pinning), which is discussed in step five. However, if the owner cannot control the pet’s access to the “good thing,” negative punishment is not the right choice. Behavior that is internally reinforced because it makes the animal “feel better” will not be much affected by any kind of punishment. Barking and meowing, for example, may release tension as a result of fear or anxiety, so ignoring the behavior will not help decrease the frequency of these kinds of vocalizations.

Examples of situations in which negative punishment can be applied instead of positive punishment are:

• Pet paws at person who is petting her—person stops petting and walks away

• Dog attempts to dash through door before being given permission—owner shuts door and walks away

• Bird screams for attention—owner covers the cage with a towel

• Dog will not release toy for owner to throw—owner walks away and refuses to play with dog

• When told to sit, dog lies down instead—owner withholds tidbit

• Cat A stalks family cat B—cat A is put in a small bathroom for 3 minutes

The last example is a timeout, a “take-away” technique. Technically, the term is “timeout from reinforcement.” Practically a timeout means that as a consequence of unwanted behavior, the animal is immediately taken to a place where he does not want to be. A kitten that bites during play can be immediately placed in a small, dark room for a few minutes.

Although theoretically a quite useful technique, using a “timeout” effectively often presents some logistical difficulties. One is finding an appropriate timeout location. Putting a dog outside for a “timeout” if it plays too rough inside will stop the behavior at that moment, but will not have any value in preventing rough play in the future if the dog enjoys being outside.

After episodes of misbehavior, owners often confine their pets for hours in a garage, crate, or small room or ignore them for days, thinking prolonged periods of deprivation will be more effective than shorter ones. This is erroneous. Longer “timeouts” are not more effective than shorter ones. Technicians should actually recommend that owners set a clock to remind them to release the animal from its timeout after about 15 minutes.

Step Five: Minimize “Discipline” (Positive Punishment) and Use It Correctly When Necessary

When the other four steps are followed, discipline becomes less necessary.

For punishment to be used effectively and humanely, several criteria must be met. Some of the more important criteria for effective punishment are as follows.

Immediacy: Any punishment must be delivered within a few seconds after the undesirable behavior occurs. Any longer delay prevents the animal from associating the punishment with the unwanted behavior and increases the likelihood that the pet has performed another behavior before the punishment is delivered. Pet owners mistakenly believe that if a pet can be shown the results of its misbehavior, such as a puddle on the carpet, trash on the floor, or a damaged personal item, the animal will make the connection between past behavior and later attempts at “discipline” when delays of short or long duration separate one from the other.

This belief stems from owners’ observations of what they label “guilty looks” when they attempt to deliver punishment after the fact. Such behaviors that dogs display are nothing more than submissive behaviors triggered by the owner’s presence and/or her threatening behavior directed toward the dog. Rather than showing submissive behaviors, cats generally hide when they are intimidated.

Some pets learn to determine that when the owner comes home and there is a mess somewhere in the house (trash overturned, feces on the floor, a torn-up couch cushion), bad things will happen to them. If the owner comes home and there is no mess, nothing bad happens, and the pet displays normal greeting behaviors.

Consistency: All occurrences of the undesirable behavior must be punished for punishment to be most effective. If an owner catches the pet misbehaving some of the time but not all of the time, it is likely the behavior will continue because the pet continues to play the odds that it will not be punished. With most behaviors, it is unrealistic to expect owners to be available to immediately and consistently deliver a positive punishment. This is one reason that there are a limited number of situations and problems that can benefit from owner-delivered positive punishment.

Appropriate Intensity: Animals will learn to tolerate higher levels of aversive stimuli if they are presented with such stimuli in gradually increasing intensity rather than initially experiencing a moderately intense stimulus. For example, an owner might gently tell his or her dog “no,” which is not sufficient to stop the misbehavior. The owner may say “no” in gradually increasing threatening tones until it is necessary to scream at the dog to get him to stop the behavior. In contrast, an owner who says “no” in a more firm, authoritative tone of voice initially is more likely to successfully stop the misbehavior and not have to scream. Unfortunately, many aversive stimuli that are intense enough to inhibit behaviors can also elicit fearful and aggressive responses.

Remote Punishment Is Usually Preferable to Interactive Punishment: Positive punishment that comes from the owner has several potentially undesirable outcomes. First, the pet often learns that a behavior will be punished only in the owner’s presence. The cat thus scratches the stereo speaker or the dog lifts his leg on the couch only when the owner is at work. This leads owners to incorrectly and anthropomorphically conclude that the pet “knows better” because the behavior only occurs when the owner is not present. Second, owner-delivered punishment, especially if it is severe (scruff shakes, rollovers, hitting) or does not meet the other criteria, can result in the pet being afraid of or aggressive toward the owner and has a negative impact on the human-animal bond. Remote punishments or booby traps are more likely to be immediate and consistent. Examples of remote punishers are as follows:

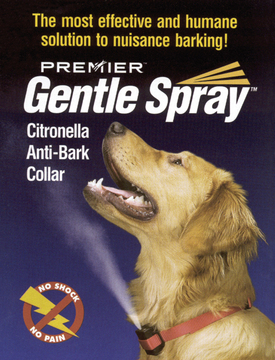

• Citronella Anti-Bark Collar (Premier Pet Products) (Figure 11-7)

• Motion detector (SSSCAT, Premier Pet Products) (Figure 11-8)

• Scat Mat (Contech, Inc.) (Figure 11-9)

• Hand-held noisemaker, such as an air horn (Safety Sport) (Figure 11-10) or ultrasonic device

• DirectStop, a harmless spray of dilute citronella oil that nonetheless most pets find unpleasant because of its odor and startling delivery (Figure 11-11)

These last two products require activation by the owner, who must be able to covertly, immediately, and consistently activate them.

By definition, punishment decreases the frequency of the behavior it follows. If an owner has repeatedly attempted to punish a behavior but the pet is still showing the behavior at the same frequency, then the behavior has not really been punished.

A general guideline that technicians can give owners is that if positive punishment has not been successful after three to five applications, it probably will not be successful. Either this is not the best technique for the problem, or it is being implemented incorrectly.

Even more importantly, technicians should encourage owners to shift their perspective from “how can I get my pet to stop a certain behavior?” which implies the need for some sort of aversive consequence, to “how can I get my pet to do what I want so I can reward it?” With this perspective, the first three steps of the five-step plan are usually the most important.

Examples of how the five-step plan can be applied to canine house training and to introducing pets to one another can be found in Box 11-14 and Box 11-15, respectively, and a list of behaviors and situations for which technicians should provide owners a five-step plan is provided in Box 11-15.

BEHAVIOR ASSESSMENTS

A recent study showed that as few as 25% of veterinarians routinely discuss behavior issues with clients, 17% never do, and only 11% of veterinarians thought it was their responsibility to initiate discussions about behavior problems with clients (Patronek and Dodman, 1999).

A behavior wellness approach requires that technicians and other veterinary professionals take the initiative during every wellness appointment and perhaps other nonemergency appointments to perform regular behavior assessments. If they do not, opportunities for helping owners create desirable behavior and for early detection and intervention when problems do arise will be lost.

Owners will resort to inquiring about behavior only at the crisis stage in which the pet’s continued presence in the home is at risk. With the support of the veterinarian, trained technicians are best positioned to conduct behavior assessments before the start of the medical appointment.

Behavior assessments involve the following five major areas:

1. How well the animal meets the criteria for a behaviorally healthy pet

2. Family conditions or changes that put pets at risk for surrender

3. The pet’s daily routine, lifestyle, and whether its behavioral needs are being met

How Well the Animal Meets the Criteria for a Behaviorally Healthy Pet

For each behavior listed in Box 11-16, owners can be asked to rate their pet’s behaviors on a 5-point Likert scale (always, usually, sometimes, rarely, or never). Technicians can discuss in depth those behaviors that owners rank as “rarely” or “never.” Certain behaviors may be sufficiently important to discuss, even if an owner rated them as “sometimes.” A pet that is only “sometimes” friendly with people may have an aggression problem that requires immediate assistance. A checklist form of these behaviors can be downloaded for free from www.AnimalBehaviorAssociates.com.

Family Conditions or Changes That Put Pets at Risk for Surrender

A move, addition of a new baby, a change in a family member’s schedule, vacation, remodeling, and the addition or loss of another family pet are all examples of changes that frequently trigger behavior problems. If impending changes are identified, additional behavioral services can be provided to pet owners to help them proactively prepare their pets and minimize the potential negative effects on the pet’s behavior. Examples of questions to ask are provided in Box 11-17.

The Pet’s Daily Routine, Lifestyle, and Whether Its Behavioral Needs Are Being Met

Recent research shows that where a pet spends its time during the day may be a risk factor for relinquishment. One study revealed that dogs who were confined in crates, left outside, or confined to a small part of the house on a routine basis were at a greater risk for surrender to a shelter than those who had free run of the house (Patronek et al, 1996a). Similarly, cats that were allowed outside were also at a greater risk (Patronek et al, 1996b). Thus it may be important to find out where the pet spends most of its time.

Problem behaviors can occur when an animal’s behavioral needs are not being met or when the animal is getting its needs met by using inappropriate behaviors. Technicians can inquire about the pet’s behavioral needs based on the categories in Box 11-12. Box 11-18 gives examples of questions regarding the pet’s routines and whether the pet’s behavioral needs are being met.

Identification of Early Warning Signs of Problems

Owners often do not interpret behaviors as early warning signs of potential problems, such as the following:

• The dog leaves the room and avoids an infant whenever the infant is placed on a blanket on the floor. The owner may not understand that this is an indication that the dog is fearful, a behavior that could escalate to growling and snapping when the infant reaches the crawling or toddler stage.

• The cat often urinates right next to the litter box. The owner tolerates and never mentions this behavior because it occurs on cement in the unfinished basement. The owner may not have the foresight to see that when he or she decides to finish the basement, this will likely result in the cat urinating on the new carpet.

• An owner who reports the adult dog that they just added to their home is “just fine” when meeting and greeting new people, but you observe the dog to be quite still, eyes wide and dilated, and without any evidence of friendly behavior when you approach him.

• A dog owner who is a teacher has been home all summer with a new puppy. She or he thinks it is cute that the puppy cries, paws, and becomes distressed at the door when the owner steps outside for a short time to get the mail or mow the yard. The owner does not view this behavior as an indication of a potential separation anxiety problem when she or he goes back to work in the fall.

The important point in these examples is that the owners would never think to discuss these behaviors with the technician because they do not see them as problems or potential problems. People surrendering their pets to a shelter had often experienced some lifestyle change that either prevented them from continuing to tolerate the problem or, as in these examples, resulted in the same behavior becoming less tolerable (DiGiacomo et al, 1998; Scarlett et al, 1999). A behavior assessment can be used to detect these situations and identify problems or potential problems earlier.

Box 11-19 gives examples of questions that technicians can ask owners for the purpose of identifying these warning signs. Things owners mention that the animal does not like and activities that elicit fearful, threatening, aggressive, or avoidance behaviors may later be associated with full-blown behavior problems.

The Pet’s Behavior Observed at the Veterinary Hospital

Technicians should make note of the pet’s demeanor at the veterinary hospital. This is important not only in assessing the pet’s behavioral health, but in keeping the staff safe when handling the pet. Occurrences of fearful, threatening, or aggressive behavior should be put in the patient’s record, shared with the staff, and discussed with the owner. It is a good idea to mark the front of a fractious or dangerous patient’s file with a hard-to-miss symbol so that technicians are aware of the patient’s behavioral history before attempting any interactions. In addition, technicians should receive clear instructions or protocols from the veterinarian as to what they should do differently when a patient identified in this way comes into the hospital.

When technicians observe dangerous or threatening behavior from a patient, they must discuss this with the veterinarian. The veterinarian must in turn share this information with the owner. Under the veterinarian’s direction, technicians may be asked to discuss these problems with the owner. Veterinarians and technicians can prepare a script for the conversation with the owner. Examples of discussion points are listed in Box 11-20. To gain a sense of the breadth of the problem, technicians should also ask the owner whether the pet has displayed similar behavior in other contexts.

Interpersonal Skills to Use During Behavior Assessment

Interviewing Skills: Asking Good Questions: Initiating discussions requires excellent interviewing skills. Such skills are important not only in behavioral wellness programs, but also during the process of taking a medical history. The first important interviewing skill is asking nonleading, open-ended questions. Good questions do not lead the client into a particular answer and require more than a yes or no answer. Questions such as “Is your pet showing any problem behavior?” or “Do you have any questions about setting up a litter box?” do not meet these criteria. A client could answer both questions “no” and yet have a 6-month-old dog who growls when people come too close to the food dish (the owner thinks this is normal and therefore not a problem), or the owner may have located a new kitten’s litter box in the basement on a cement floor next to the furnace (the owner sees nothing wrong with this placement and thus has no questions). More productive questions might be: “What does your pet not like you to do with him?” and “Would you describe your kitten’s litter box to me?” Follow-up questions may be necessary, and the technician may need to ask the same question in several ways to obtain concrete, detailed information.

Interviewing Skills: Interpersonal Communication: For owners to provide good information about their pets, they need to feel comfortable talking to the veterinary technician. Clients need to know that technicians are not just “going through the motions,” but are genuinely interested in them, their pets, and what they have to say. Even on a busy day, a harried technician can make a good impression and encourage clients to open up, while at the same time keeping the conversation on track, by using a few simple communication skills.

Put clients at ease by sitting down: Conducting the behavioral interview sitting down puts the technician and client at the same level and also helps relieve any tension or nervousness. The technician who remains standing gives the impression of being in a hurry or less approachable. Having clients sit down helps to relax them and put them more at ease.

Use active listening skills: A technician should face clients when talking to them to communicate that the clients are the focus of attention. If the technician’s body is directed elsewhere, the message is that so is his or her attention. The technician can keep an open body posture by trying not to cross legs or arms, hold a clipboard or folder at chest or face level, or stand behind a barrier, such as an examination table. Doing so sends the message that the technician is not completely open to hearing the client. Maintaining casual eye contact by looking at the client from time to time, rather than burying one’s face in papers, enhances communication. Looking up while still being able to take notes takes practice, but it is a skill worth developing. The technician can acknowledge what the client is saying by giving frequent feedback without interrupting; by nodding his or her head; by saying “OK,” “Hmmm,” or “I see”; or making other neutral, quick statements to let the client know that the technician is engaged in the conversation. A warm or neutral tone of voice, rather than an abrupt or abrasive one, should be used.

Obtain behavioral descriptions, not interpretations: Owners often describe their pets’ behavior in relatively vague terms, such as “He goes crazy at the door!” Consider the following three examples of what this statement might actually mean. When the doorbell rings, the dog does the following:

• Barks, growls, runs to the door, and lunges at the people he sees outside

• Wildly jumps up, grabs his ball, races to the door, tail wagging, with a “happy face,” and thrusts his wet, slimy ball into the visitor’s hand

• Barks continuously, shies away from the door, hides behind the owner, and will not allow visitors to get near him

These are just three of many possible things that “He goes crazy at the door!” might mean. This illustrates the importance of obtaining behavioral descriptions, rather than interpretations. The technician can ask, “What does your pet do at the door? Describe the behaviors you see.” The technician should continue to probe for additional information until he or she is certain what a client is attempting to describe. Repeated questioning may be necessary to obtain descriptions that provide a mental picture of the behavior in question. While probing for more information, the technician should use good communication skills so that clients understand that he or she is genuinely attempting to clarify information rather than harassing them with repeated questions. The technician can paraphrase a client’s description of the pet’s behavior by asking, “So when the doorbell rings, your dog barks and jumps on people—is that correct?” This question gives the client an opportunity to agree with the technician or provide additional information.

Using the Results of Behavior Assessments

The behavior assessment should be made a part of the pet’s permanent record, and the technician should discuss the results with the veterinarian. An action plan could include a medical examination, an in-house behavior consultation, referral to a behavior consultant, referral to a dog trainer for obedience classes, dissemination of educational materials, or a recommendation for particular behavior-management products. The veterinarian may ask the technician to present or assist in presenting all or part of this action to the client. Technicians should be sure that they understand what role they play in delivering this information and avoid taking it upon themselves to develop any part of this action plan—including referrals—without approval from the veterinarian.

Follow-Up for Behavior Assessments

Once the veterinarian has created an action plan, technicians can be responsible for conducting behavioral follow-up telephone calls, just as many currently do for medical cases. After routine surgeries, suturing, or dental procedures, technicians are often given the responsibility of calling clients to inquire about the pet’s status and progress. Behavior issues deserve the same type of follow-up. Technicians can call the client to determine whether the pet owner followed through with the suggested referral, implemented any training or behavior modification techniques that were suggested, or purchased behavior-management products that were recommended. Technicians can also help owners implement a behavior modification plan created by the veterinarian or outside behavior consultant. Few veterinary practices have routine procedures in place to follow up on behavioral problems in the same way they follow up on medical problems, so well-informed technicians have the opportunity to set important precedents.

MAKING THE VETERINARY PRACTICE A BEHAVIORALLY FRIENDLY PLACE

Visiting the veterinary practice is stressful for some pets and consequently for their owners. An animal that is stressed or fearful is more likely to injure a staff member. Animals in such states are more difficult to handle and consequently may not receive the best possible medical care. Each visit that results in stress and unpleasantness for the pet ensures that future visits will become more difficult.

One of the ways pet owners judge the quality of the veterinary hospital, the staff, and the services provided is by how their animals are treated. Using behaviorally friendly methods with patients is “walking the talk” of behavior wellness care. Clients will better understand the idea of behavior wellness care when they see technicians use positive and proactive techniques when handling their pets. It is to everyone’s benefit to take a behavior wellness approach and help patients be more relaxed at the veterinary practice. Rather than having to calm down animals that arrive at the practice already stressed, a proactive behavior wellness approach seeks to create patients that have positive expectations when they arrive at the veterinary practice.

The first step in lowering patient stress is to understand species-typical behaviors when an animal feels threatened or challenged.

Understanding Social Conflict Behavior

When animals feel threatened or challenged in social interactions, they have a variety of choices as to how to respond. These choices are called agonistic behaviors. By understanding the choices animals may make in social conflict situations, technicians can often decrease conflict, more humanely handle and restrain animals with less use of force, and be safer themselves. The most common agonistic behaviors technicians are likely to see in a veterinary medical context are described in following sections.

Escape and Avoidance: Many animals initially try to avoid conflict. Animals may try to get away or struggle to avoid restraint. Sometimes it may be better to allow the animal to avoid conflict rather than escalating forceful restraint. Backing off, giving the animal a chance to calm down, and trying other techniques are safer choices for the technician and less stressful for the animal. Allowing avoidance to “work” for the animal is usually not as bad as forcing the issue and escalating the situation until the animal and possibly the technician are out of control.

An animal that is trying to escape and avoid conflict is not trying to “be dominant,” a common misinterpretation of the situation. Although there is the rare patient that is offensively motivated in this way, if the technician pays close attention to the animal’s body language, using the information given later in this chapter, it will be easy to recognize the difference.

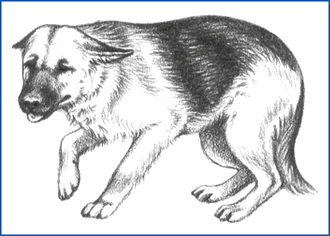

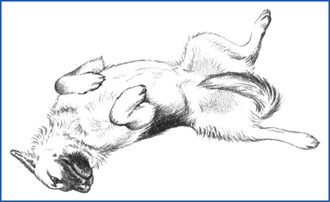

Submissive Behavior: Dogs that show passive submissive behaviors (Figure 11-12) when threatened are not dangerous to handle. They are acquiescing, or “giving in.” Technicians should handle and restrain such animals gently. Some submissive behaviors, such as lowered ears and tail and a crouched position, are also displayed when a dog is fearful (see Figure 11-24), so technicians may ease the dog’s stress by changing their behaviors so as to appear less threatening.

FIGURE 11-12 Submissive dog. Canine submissive postures and behaviors include rolling over or crouched body posture, avoidance of eye contact, low tail carriage, ears back, whining, and/or a submissive grin. (Copyright 2008. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals® [ASPCA®]. All Rights Reserved.)

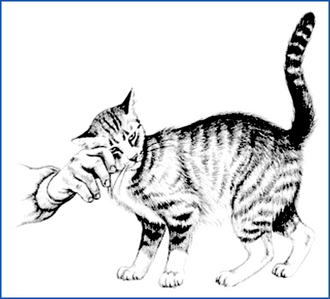

Cats and other species of animals that do not live in structured social groups typically do not show submissive behaviors. When cats cannot avoid conflict, they typically become defensively threatening or aggressive (Figure 11-13). Cats may sometimes be fearful without being threatening (Figure 11-14).

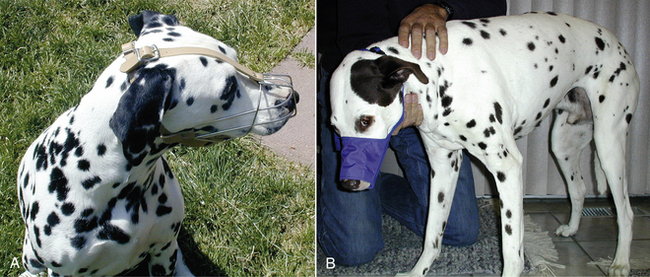

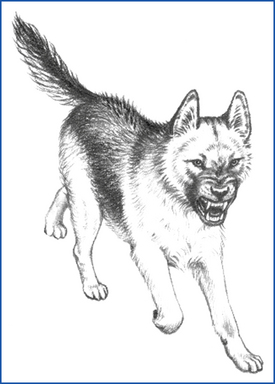

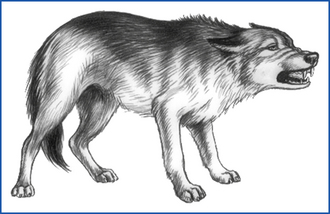

Threatening Behavior: The goal of threats is to warn, not to harm or hurt. Many behaviors that are commonly referred to as “aggression” are more accurately categorized as threats. These include baring teeth, growling or hissing, lunging, barking, scratching, and attempts to bite or inhibited bites. Animals that “air-snap” or bite without injury are being threatening. It is generally not true that a technician can avoid a bite by being quicker than the animal. Rather it is usually the case that the animal was never intent on biting, only on threatening. Threats can be either offensive or defensive. An offensive threat is accompanied by the body postures seen in Figures 11-15 and 11-16. Defensive dogs and cats are shown in Figures 11-13 and 11-17. Animals are much more likely to be defensive in a veterinary context. This means they are both fearful and threatening. Defensive animals do not take the initiative to charge their opponents and will not bite if left alone. Offensive animals can lunge, charge, and chase their targets.

FIGURE 11-15 Offensively threatening dog. Canine offensive threats include upright ears, tail carried high, direct stare, piloerection, baring teeth with vertical lip retraction, stiff upright body carriage, and barking or growling. (Copyright 2008. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals® [ASPCA®]. All Rights Reserved.)

FIGURE 11-16 Offensively threatening cats. Feline offensive threats include a stiff upright posture, direct stare, ears upright, piloerection, tail stiff and held straight down. The tabby cat on the right has a slight arch to its back, indicating a small defensive component to its behavior.

FIGURE 11-17 Defensively threatening dog. Canine defensive threats include avoidance of eye contact, crouched posture, ears back, tail down, teeth bared with horizontal retraction of the lips, barking or growling. (Copyright 2008. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals® [ASPCA®]. All Rights Reserved.)

Technicians should always assume that threatening behaviors can escalate into aggression at any moment.

Aggressive Behavior: Aggressive behavior harms the opponent. Threats and aggression can overlap. An animal may initially respond to a threat by showing threatening body postures, but may eventually bite or snap. Whereas a bite attempt that never touches the opponent is clearly a threat, a bite that leaves a red mark, indentation, bruise, or other minor injury is in an area of transition between a threat and aggression. As with threats, most aggressive behavior that technicians will see in the veterinary context is likely defensive rather than offensive. This is why it is so important for technicians to use the proactive, nonthreatening techniques to be discussed to prevent patients from becoming fearful and feeling the need to defend themselves.

Using Puppy and Kitten Classes to Socialize Young Animals to the Veterinary Practice

Puppy and kitten socialization classes, which have already been mentioned, are one way to help create positive expectations and associations with the veterinary practice. These socialization classes can help young animals become familiar with the sights, sounds, and smells of the practice under enjoyable conditions. During class, young animals can be put on the scale and an examination table and subjected to brief handling procedures paired with treats and petting. This allows them to become somewhat familiar with the staff and with the physical environment. When they come for their next appointment, they will be entering a familiar environment, expecting the same sort of pleasant experiences they had during class and will therefore be easier to handle.

When difficult-to-handle adult animals are identified, technicians can suggest that veterinarians encourage “remedial” socialization visits. Owners are asked to bring the patient in for a brief visit during which only “good things” happen. Perhaps the animal is petted, given a tidbit, and placed on the scale. With each succeeding socialization visit, the staff handles the animal a bit more and creates situations that the animal might experience during an examination.

Using Behavior Assessments

Technicians should be aware of the results of patients’ behavior assessments (Boxes 11-17 through 11-19) before handling them. By a forewarning about what a pet does not like, how the pet reacts to everyday handling, and whether the pet has shown aggressive or threatening behavior under certain circumstances, the technician can be better equipped to prevent the patient from becoming fearful and stressed. Technicians must be sure to take the time to include information gleaned from behavior assessments in the patient’s record. Not doing so puts fellow staff members at risk, and the value of behavior assessments will be lost if the information is not recorded.

Establish a Positive Expectation in the Waiting Area

The emotional reactions patients have in the waiting or reception area will affect their arousal level when they are examined. If experiences in the waiting area increase patients’ arousal, patients will be more difficult to handle. Such experiences, particularly with cats, are common triggers for aggression later redirected toward technicians. Technicians can assess the waiting area from the patients’ point of view. What do the animals see and hear when they first enter the door to the veterinary practice? Does the staff approach too quickly? Is a dog close enough to sniff and frighten a cat in a carrier or to lunge at another dog?

Manage the Environment

Animals that are upset or overly excited should be moved out of the waiting area as quickly as possible. This not only helps to lower their arousal, but also prevents them from agitating other patients. Technicians can move these animals into an examination room as soon as possible or even an office area if an examination room is not available. See-through cat carriers, such as wire crates, should be covered immediately so that cats feel safer. If the practice’s location and weather permit, technicians can suggest that owners leave patients in the car until their appointment time or take dogs for a walk around the building or parking area.

Structural barriers, such as half walls (Figure 11-18) that create individual cubicles, are helpful additions to reception areas. Plants or other inanimate objects can be used to block patients’ views of one another. Chairs can be arranged to create more space between patients and placed back to back so that pets and their owners are not sitting across the room facing one another. Owners can be asked to position their pets or their carriers so that the animals are facing them (or a wall) rather than another patient. Ideally, cats and dogs should have separate entrances or at least be segregated into different sections of the waiting area.

Interactions With Staff: Greetings

Technicians must know how to approach patients in a nonthreatening way. The behaviors most people use to greet dogs are all, to the dog, offensive threats. These postures are listed in the left-hand column of Table 11-3 and illustrated in Figure 11-19. Cats also tend to perceive these postures as threatening.

TABLE 11-3

Postures to Avoid When Approaching Fearful or Unfamiliar Dogs

| Postures to Avoid | Appropriate Postures |

| Direct eye contact | Look at the floor, off to the side, or above the dog’s head |

| Frontal approach | Turn the side of the body toward the dog or approach at a slight angle rather than head on |

| Reaching toward or over | Allow the dog to approach, let the dog sniff a hand held at the side of the body, pet the dog from under the chin |

| Leaning forward, over | Bend at the knees or stand straight up over the dog’s body |

FIGURE 11-19 Threatening-appearing greeting. Person is reaching over dog’s head, facing dog, and leaning over dog.

Technicians must develop the habit of using nonthreatening behaviors when greeting patients. In general, these are the opposite of the behaviors described previously and are listed in the right-hand column of Table 11-3 and illustrated in Figure 11-20.

FIGURE 11-20 Nonthreatening greeting. Person has turned side of body toward dog, is not bending at the waist, and is petting dog under chin.

When possible, technicians can allow the pet to approach them rather than invading the animal’s personal space. These nonthreatening behaviors make an immediate, significant, observable difference in patients’ behaviors.

Before petting a cat, the technician should first allow the cat to sniff either a finger or an inanimate object, such as a pen (Figure 11-21). This mimics a typical friendly cat-to-cat greeting of sniffing noses (Figure 11-22). Many cats do not like to be stroked down their backs or patted on the head, particularly by an unfamiliar person. Instead, technicians can rub cats on their scent glands located on their cheeks and in front of their ears (Figure 11-23).

FIGURE 11-21 Friendly cat greeting person. Cat is sniffing the person’s finger, similar to how it would sniff the nose of another cat.

FIGURE 11-23 Recommended way to pet an unfamiliar cat. (Copyright 2008. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals® [ASPCA®]. All Rights Reserved.)