Nursing Concepts in Alternative Medicine

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

1 Describe considerations in the development of home-prepared diets for dogs and cats.

2 List the commonly used nutraceuticals and describe their therapeutic uses.

3 List the commonly used Western herbs and describe their therapeutic uses.

4 List the common ingredients found in Chinese herbal and ayurvedic herbal formulas.

5 Describe the principles of aromatherapy and list common aromatherapy oils and their uses.

6 Describe the basic principles of homeopathy and list forms of homeopathic preparations and considerations for storage and administration.

7 Describe the principles of flower essence therapy and list common flower essences and their uses.

8 Define applied kinesiology and list the techniques used for a patient’s assessment and treatment.

9 List the theories that describe the principles of acupuncture and describe the role of the veterinary technician in acupuncture therapy.

10 List and describe the physical modalities used in alternative and complementary medicine.

ALTERNATIVE CONCEPTS IN NUTRITION

One of the most commonly asked questions in veterinary practice is “what should I feed my pet?” Quite often, the technician is the staff member responsible for educating clients about nutrition. This is an important way that you can influence the health of your patients and become an outstanding part of the veterinary health care team. Basic nutrition is essential knowledge for every technician in every practice, with no exceptions. Even in a surgical referral practice, counseling clients on proper nutrition to optimize surgical recovery is an important aspect of providing the best and most complete health care. This section is meant to expand upon basic knowledge of animal nutrition and introduce some novel concepts in companion animal nutrition.

Nutrition becomes an even more commonly discussed issue in holistic practice because it is the foundation of achieving a state of ideal health. Many clients who seek alternative care for their pets are already educated about nutrition, sometimes even more than the staff. On the downside, misinformation and hype abounds, especially in the Internet age. It can be difficult to convince a client that a vegetarian diet is inappropriate for cats when the lady at the health food store swore it cured her Fluffy’s cancer. It is therefore becoming an important issue in any practice because these clients need sound nutritional advice from an “expert” who is confident and well informed. Whether or not you or your veterinarians advocate a holistic approach to nutrition, it is imperative that you understand it and can justify your recommendations to these well-informed but sometimes misinformed clients.

A good holistic diet is based on using whole, natural ingredients in a balanced ration. For small animals, the most wholesome healthy diet is a balanced, home-prepared diet. In the case of herbivores, the best diet is pasture provided on a soil with balanced minerals, supplemented with hay and grain only when necessary. The term balanced is an important one because an improperly prepared or unbalanced diet can cause disease or at least be a hindrance to attaining ideal health. Balance can be achieved with each meal, as it is with commercial pet food, or it may be achieved on a daily to weekly basis, as our own diets do.

It is also important to note that a healthy water source, such as spring water, is as significant to the patient’s overall health. Water can be a source of healthy vitamins and minerals, or it can contain harmful toxins and additives. A good rule of thumb is if you would not drink your tap water, neither should your pet.

Some recommendations may simply be unattainable for our large animal patients, but we can do our best to optimize the resources that are available, such as proper pasture management and using sources of good-quality hay and grain, along with supplementation to balance the mineral and vitamin component of the diet. Soil testing and hay analysis for nutrient content is reasonably accessible and should be used regularly as food sources change.

We will now discuss home-prepared diets in a little more depth. Meat used in the home-prepared diet for carnivores may be raw or cooked, depending on the owner’s preference and the pet’s constitution. Raw diets are quite an area of controversy, and there is a great deal of information available on this topic. The theory behind raw diets is that a wild carnivore (feline or canine) catches prey and eats it; no cooking involved. Raw meat does contain more enzymes and is truly more “what nature intended.” It is more highly digestible and contains more unspoiled nutrients than the cooked version (think about our vegetables). Although this is certainly undeniable, most people are unable to provide a fresh catch for their domestic cat or dog. Our raw meat is processed and packaged. This brings about the problem of bacterial contamination, which the carnivore is generally (but not always) well equipped to handle because of the more acidic pH of the stomach and intestines. The risk increases with ground meat, which has a higher surface area exposed to bacteria. Bacterial contamination is actually much more of a concern to the humans in the household who will be handling the food. Care must be taken to educate clients about the health risks posed to them and their families, especially when there are young, elderly, or immunocompromised members of the household. Basically the same procedures and precautions must be taken when handling raw meat that will be cooked: immediately clean and disinfect any surface that the raw food touches, including your hands.

Where raw bones are concerned, it is true that they do not splinter or break teeth as cooked bones do, but they are not without their dangers.

On the subject of vegetables, these should be cooked (lightly steamed) and chopped or minced or grated because carnivores are less able to break down plant cell walls to obtain the nutritious substances inside. Generally, in the wild, the most substantial plant source is what is contained in the herbivorous prey’s GI tract. This has already gone through part of the digestive process, and the nutrients are thus available for use by the carnivorous predator. There are now a variety of excellent, well-balanced commercially prepared raw diets. These come in both frozen and freeze-dried form and are becoming more readily available to pet owners. Some are even designed to be single-serving packages to minimize the need for directly handling the food. The bottom line on raw diets is that they can be a wonderful way to enhance an animal’s health if properly prepared and balanced, but they are not indicated for every pet, nor are raw diets the cure for every disease or disorder.

Holistic-oriented commercial diets are also becoming more readily available. Many companies producing dry and canned food are including holistic product lines, and many smaller companies are focused solely on providing holistic diets for pets.

A recent contamination of grain imported from China resulted in numerous pet deaths, and many of the affected diets had an excellent mix of ingredients. Some of the recalled foods were considered to be high-quality, holistic diets. At this point, it may be best to steer clients to diets that obtain all ingredients from the United States, Canada, and New Zealand (which produces the majority of lamb for our pet food).

One newer trend in the pet food industry is the limited grain or grain-free diet. This mimics the nutrient profile of a raw diet without the concern for contamination. In addition, many of these diets are dry, which makes the convenience quite appealing. Some other dry diets are baked rather than extruded, providing a more natural nutrient profile with better digestibility.

Supplementation of the diet with probiotics and digestive enzymes may also be beneficial, particularly for those pets and breeds (such as the German Shepherd) that tend to have sensitive digestive systems. Addition of plain yogurt is a simple way to help balance the GI tract, but many commercially prepared products are also available.

Each patient must be assessed to find the best diet for him or her that is also feasible for the caretaker. An acceptable alternative to home-prepared meals may involve choosing several (three to four) commercial diets and rotating them to provide an overall balance in nutrients. For example, one diet may give an animal less than an ideal (although meeting minimum requirements) amount of a certain micronutrient. By rotating diets, this will likely balance out in the long run because another diet may have more of that nutrient (Case Presentation 23-1).

NUTRACEUTICALS

The use of nutraceuticals is quickly becoming more mainstream in both human and veterinary medicine. The term refers to nutritional supplements that are not herbs and not approved for use as drugs, but are thought to convey therapeutic benefit to the patient. There are many types of nutraceuticals. They are used to treat many conditions and assist in maintaining the general health and well-being of the

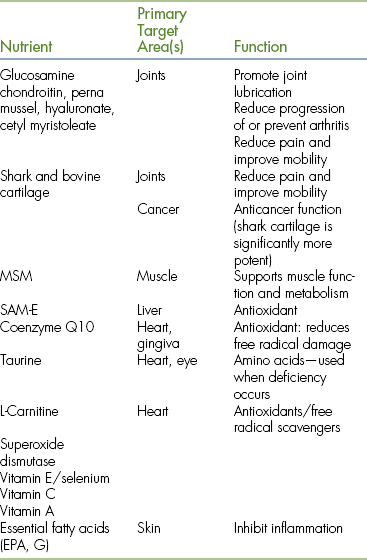

patient. The following is a brief list of the more commonly used nutraceuticals (Table 23-1).

GLANDULARS, CELL THERAPY, AND GLANDULAR-LIKE PRODUCTS

As the name implies, this type of supplement uses animal products to supply nutrients (steroids, enzymes, and raw materials of some organs, such as liver) to the patient. The theory behind use of glandulars is that by providing sources of whole tissue to a subject with a dysfunctional or suboptimally functioning organ or gland, the patient will receive the necessary substances to improve function and in some cases heal his or her own diseased tissue. A good example of this is to provide a product containing bovine thyroid gland for a patient with a low thyroid level.

Like any food ingredient, it is important to have a reputable source for these products because they are made from animal products. There are a handful of companies in the United States that use human grade ingredients in their products and have rigorously standardized and tested their products. These companies often provide guidelines for dosing and administration to animals. One company is now making products specifically for dogs and cats, using a powdered form that is quite palatable. This type of therapy is also sometimes a moral and ethical dilemma for holistic practitioners because of animal use, but the more reputable companies try to be as ethical and humane as possible in their formulations.

The technician should be familiar with the glandular-type and nutraceutical products used within the practice. He or she should be aware of the many types of diets that are appropriate and inappropriate for patients and should be able to explain the veterinarian’s recommendations.

HERBAL MEDICINE

Herbal or botanical medicine refers to the practice of using plant materials (including flowers, stems, leaves, bark, seeds, roots) to treat patients. Herbal medicine is the most ancient known medicine and the foundation of modern medicine. Using plants as medicine predated written communication, and evidence of the use of plants is widespread in ancient cultures. It is still a large practice in the world today, with an estimated 80% of the world’s population using this form of therapy as a primary means of health care. Even today, about 20% of our drugs are derived from a plant source. The technician should become familiar with the herbal pharmacy, just as he or she knows about the drugs on the shelf.

Information about the medicinal use of herbs can be found in the Materia Medica, which is similar to a drug formulary.

Many have not been proven safe in pregnancy, and some are toxic to cats. This is important to remember because many clients equate herbs with complete safety and need to be educated on their proper use and side effects, just as they should with any medication prescribed.

In the United States, herbs are regulated as a food. The FDA requires a rigorous testing procedure to approve a substance as a drug, at a cost to the manufacturer of more than $230 million. Because a natural substance cannot be patented, no pharmaceutical company would fund the research required for approval. Currently, we rely mainly on testing based in Europe and Asia to substantiate the effects of herbal therapy. Unfortunately, this does nothing to assure us of the quality or purity of the products because of the lack of FDA regulation. The herbal practitioner therefore must be cautious about the source of the prescribed herbs. This is another issue that must be emphasized to clients, who often do not understand the difference between the medication purchased at the practice versus the bottle they buy at the local supercenter.

If practicing with a veterinarian who uses therapeutic herbs, the technician should be familiar with commonly used preparations, just as he or she has knowledge of the commonly used drugs in the pharmacy. The technician may also be asked to assist in preparing and dispensing herbal products and explaining the proper use to the client.

WESTERN HERBS

Western herbal medicine is becoming a common practice in veterinary medicine. With the holistic movement in human medicine, most people are now familiar with products, such as echinacea, ginseng, and St. John’s wort. Proper dosing and administration for animals have not been scientifically proven, but doses for the more commonly used herbs have been fairly well established.

The herbs come in many different forms (Figure 23-1), and each has advantages and disadvantages when used in animal species. Bulk herbs are the most commonly used preparation for herbivores. The product is often dried and prepared (chopped or powdered). Some of the tastier herbs are also administered to carnivores in this form. Capsules and tablets are often used for carnivores because they are more easily disguised. Teas are prepared by straining the herbs into water. They are fairly easy to prepare, but not always readily accepted by animals (depending on the patient and the herb). Extracts are made by concentrating the herb in alcohol or glycerin. A standardized extract is much like a drug, where a specific amount of active ingredient is measured rather than a measurement of the herb itself. Milk thistle, for example, is often sold as a standardized extract containing 70% silymarin. Poultices and compresses are used topically for short periods. These are made by soaking the herb or extract in hot water, then allowing it to cool. The product is then held in place manually or with gauze for a short period. Ointments are also used topically and are generally left in place. Essential oils may be used topically, and some can also be taken internally in extremely dilute form. They are concentrated and must be used cautiously.

FIGURE 23-1 Commonly used herbal preparations: clockwise, left to right: capsules, tablets, tea pills, liquid, dried herbs (foreground).

Many herbs can be useful in combination. Some companies produce excellent and safe herbal combination products for animals. Beware, however, of combination formulas listed as “proprietary blend” because you do not know the exact dose of each herb in the formula, and patient safety could be at risk. Another precaution is using herbals and medications with the same effect (i.e., antiinflammatory) because of the increased risk for adverse side effects.

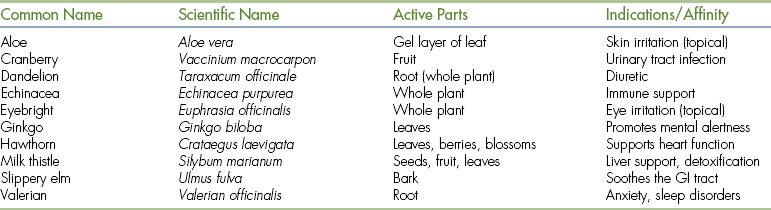

Herbs may also be used to support the general health of the patient (known as tonification). When used in this way, the herbs are taken over a long period of time. Ginkgo is often used in this way to support mental function in geriatric patients. Herbs may also be used in detoxification, such as the use of milk thistle to help protect and support the liver after steroid therapy (Table 23-2).

Administration of most herbs is generally best done on an empty stomach. For herbivores, this may be impossible. The next best way to administer herbs is with a small amount of water. Sometimes salt-free broth or clam juice works well for small animals. If food is the only way to get the herb to the patient, then try to avoid giving the herb with a full meal. It is also best to avoid any food with strong flavor, such as peppermint, near the time of administration.

CHINESE HERBAL MEDICINE

Chinese herbs actually consist of many substances, including minerals, and animal tissue. Individual botanical herbs may be used in the same way that Western herbs are. There is some overlap between Chinese and Western herbs. The main difference between the two is the use of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in a patient’s diagnosis and treatment with Chinese herbs.

TCM is further discussed in the section on acupuncture. The Chinese herbal practitioner must have a clear TCM diagnosis when prescribing an herbal therapy. This involves a TCM examination, including tongue and pulse diagnosis. Herbal medicine is considered “stronger” than acupuncture. Practitioners often use the properties and taste of the herbs to choose the most appropriate herb or formula. Most TCM practitioners in China use acupuncture only in acute cases and prescribe herbs along with it to bring about a more thorough treatment. Often for more chronic conditions or to help patients maintain health, herbs alone are used. For example, the herb ma huang, or ephedra, is used to “disperse congestion in the Lung” and “release the exterior.” In terms of TCM, the patient may be diagnosed with an exterior cold excess pattern of disease. In terms of our knowledge of pharmacology, this substance dries mucous membranes, and derivatives are used to treat the common cold, which is an exterior pathogen.

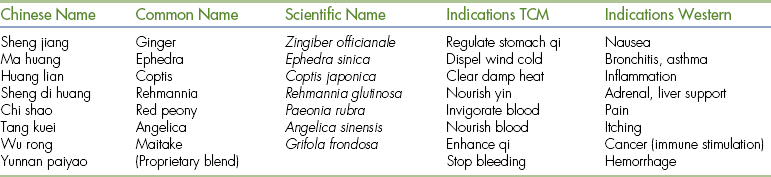

The formulas are named for their function or their main ingredients. Unlike Western herbs, each herbal formula is generally a combination of several products that work together to bring about an effect. It is a much more complex system than a Western approach. Certain herbs are found in many common formulas (Table 23-3). For this reason, the practitioner using Chinese herbs should undertake formal training. Forms are similar to Western preparation (see Figure 23-1), including tablets and pills, powders, granules, liquid teas and extracts, and topical preparations (ointments, plasters, and liniments). Many of the formulas come in tiny tablets known as tea pills. These are quite handy when treating cats, but large dogs may require 10 or more pills per dose.

As with Western herbs, and perhaps even more importantly, it is important that the herbs come from a reputable source that ensures quality control. The use of animal products in many formulations makes this a more serious concern. There are several companies in the United States that distribute products of uniform quality that are produced under the most ethical circumstances possible (e.g., some animal products from endangered species are substituted with a similar product from a related domestic animal). For some holistic practitioners, the use of animal products may result in a moral dilemma, and these veterinarians may choose to avoid these products in their pharmacy.

AYURVEDIC HERBS

Ayurveda means “the science of life.” Similar to TCM, it emphasizes health and wellness, not just treatment of disease. It originated in India and is believed to predate TCM and even to have contributed to its foundation. It includes not only herbal prescriptions, but also diet, massage, exercise, and meditation as part of a patient’s therapy. The goal of this system of medicine is to balance the three elements of nature, known as Doshas, which exist in every living organism.

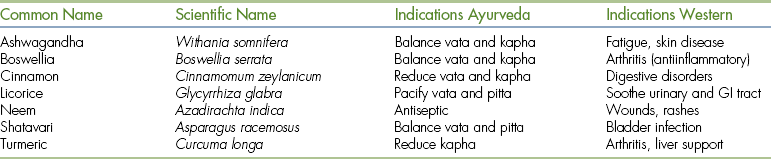

Like Chinese herbs, ayurvedic herbs may be prescribed based on pharmacology (like Western herbs), according to the three Doshas (similar to TCM yin, yang, and qi), or based on taste and temperature. For example, licorice is considered a sweet herb. Sweet herbs are considered to be cold and wet and are used to nourish and soothe. In terms of pharmacology, licorice reduces the breakdown of prostaglandin, which protects the stomach from excess acid. Thus it is a treatment for stomach ulcers, which cause a burning sensation. Ayurvedic herbs also tend to come in formulations of multiple ingredients, and like Chinese herbs, some ingredients are commonly found in multiple formulations (Table 23-4).

The technician may be asked to prepare the herbal formula, to administer, to dispense, and to explain a prescribed formula to the client. This requires a thorough knowledge of the herbal pharmacy.

AROMATHERAPY

Aromatherapy is the therapeutic use of volatile essential oils to obtain a physiologic or psychological effect (Table 23-5). Oils are distilled or extracted from plants and are considered the “last possible and most sublime” parts of the plant. Flowers, buds, fruits, peels, leaves, bark, wood, roots, and seeds can be used. The oils can be applied topically by themselves or in a massage oil, ingested (not common), or administered by nebulization (the oil is made into a mist and inhaled). The effect of inhalation is most likely due to rapid absorption by both the nasal and lung mucosa. Plants or parts of the plants can also be burned and the smoke inhaled. Potential uses of aromatherapy include antibacterial and antifungal (tea tree oil and thyme oil), relaxation or sedation (lavender oil), behavior modification (positive or negative), conditioning (citronella bark collars), and medicinal.

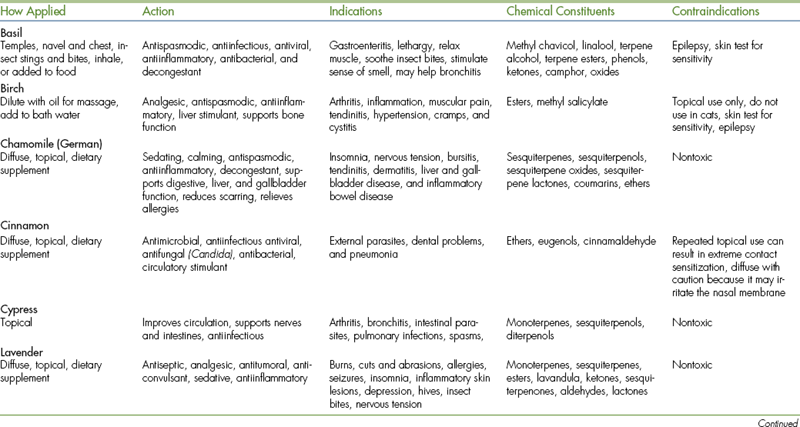

TABLE 23-5

Common Aroma Therapy Oils and Their Uses

Note: If the animal is pregnant or nursing, oils should only be used with the veterinarian’s consent. Many of these oils have not been tested on pregnant or nursing animals. Cats are more sensitive to most oils, and caution should be used when applying. Some oils that are therapeutic for dogs are toxic to cats.

HOMEOPATHY, HOMOTOXICOLOGY, AND FLOWER ESSENCES

Homeopathy is a system of medicine that is based on the principle that “like cures like.” It involves treating each patient as an individual based on his or her group of symptoms. Practitioners use extremely diluted versions of herbs and other substances, which are called remedies, to treat patients. It is sometimes difficult to understand, but it can generate amazing results when used by a skillful practitioner. Homotoxicology and flower essence therapies are similar in practice, but can often be more easily used by a veterinarian with basic knowledge and understanding.

The technician should understand the basic principles of homeopathy and be able to properly administer and store remedies, and educate clients about their proper use and handling.

HISTORY AND PRINCIPLES

Samuel Hahnemann, a German physician, first used and developed homeopathy in the late 1700s. At the time, medications were given to patients without any ensuring safety. The scientific process as we know it did not exist, and trial and error determined which substances would be good medications. At the time, quinine was being used to treat patients with malaria, but often caused as much harm as good. This pioneering practitioner through diligent perseverance ultimately recognized that symptoms of disease were expressions of the body’s attempt to restore homeostasis in response to an imbalance or insult.

The initial postulate was that giving a patient a medication that simulates the disease would stimulate the body’s own defenses, and the patient would heal. This is similar to, though not completely the same as, the principle of vaccination. It is the reverse of allopathic (or Western or modern) medicine, which uses drugs to counteract symptoms, thereby suppressing them. For example, if you use cortisone to treat a rash, your symptoms will return if you do not repeat the dose for many days, sometimes even more severely than initially experienced. You may later show signs of a more serious disease, such as a stomach ulcer. Western medicine would consider the two conditions to be unrelated, but a homeopath considers them both to be signs of disorder in the body.

Hahnemann determined that the more he diluted medicine, the stronger the beneficial effects became, whereas the harmful effects diminished or disappeared altogether. Although important, this was not his most profound discovery. Whereas most physicians were concerned with treating one symptom, the “chief complaint” as we know it, Hahnemann astutely observed that these medications had many multiple effects on the body (some beneficial, some harmful, and some neither beneficial nor harmful). He decided to try his medications, which were then completely safe, on healthy patients. For example, if you were healthy and took cold medicine, you might experience a dry nose and throat in addition to drowsiness or even inability to sleep, depending on the drug combination. He recorded everything his patients told him about the effects the medicine had on them and observed every detail that he could, from physical signs to emotions that his patients experienced. This practice is known today as a “proving.”

One of Hahnemann’s beliefs was that the medication should match the symptoms more closely. He began collecting much more detailed information about his patients, and he was able to be more precise when choosing a medicine for each individual. A perfect example is the common cold: No two persons exhibit the same exact symptoms, even though they may have the same exact virus that caused the disease. Many people exhibit the same cold symptoms each time they are sick, regardless of the strain of the virus.

Because of the safety and efficacy of his medicine, others sought to learn how to treat patients in this manner. Hahnemann recorded his philosophy and findings in a book entitled The Organon of Medicine. Homeopathy is still widely practiced today in Europe, although less so in the United States. The earliest mention of veterinary homeopathy came from Hahnemann himself, when he stated in a lecture in the early 1800s that a similar approach was also applicable to animals. Today there are organizations and courses available worldwide for veterinarians who would like to practice homeopathic medicine.

PRACTICE

When a patient is seen by a homeopathic practitioner, a clear and detailed history is essential to a successful outcome. The owner is asked many questions, some of which may seem minute and unimportant. Any previous diagnostics and therapies (and responses) should be noted, even for minor problems. The patient is observed, and details about his or her physical status and personality and reactions to certain situations are noted and recorded. This should always include a thorough “Western” physical examination because these findings may lead to symptoms not discovered by the owner (such as a fast heart rate). The veterinarian may also note something of a serious nature that may need a “Western” approach before using homeopathy. For example, an older patient in congestive heart failure that comes to the hospital dyspneic and cyanotic needs to be stabilized first. Once out of a life-threatening situation, the patient can be evaluated, and a more long-term approach can be taken.

Minute details can be important when treating patients homeopathically. Even the way the patient greets the veterinarian can be important in finding the correct remedy. All of the details are recorded, and a list of remedies that are appropriate for each sign or symptom is compiled. This is called repertorizing. From this list, the most appropriate remedy is prescribed. In modern times, much of this work can be done by computer, although some practitioners still do all of their research by hand. The remedy is then dispensed to the owner with specific instructions on dosage and administration.

Homeopathic remedies come in several strengths, called potencies. Potency is inversely proportional to dilution: the less actual substance present, the stronger the medicine. In general, it is best to use the lowest potency (or least dilute) necessary to bring about a cure. Sometimes the dose will be given only once, sometimes multiple times. The remedy should be discontinued when the symptoms cease or the patient shows improvement. Occasionally a patient will experience an exacerbation of symptoms, called an aggravation. This usually passes within a few hours and is not generally a concern. Usually, it indicates that the correct remedy was chosen, but if the patient becomes weaker, an “antidote” (another remedy) to the prescribed remedy can be given. Antidotes to each remedy are listed in the Materia Medica.

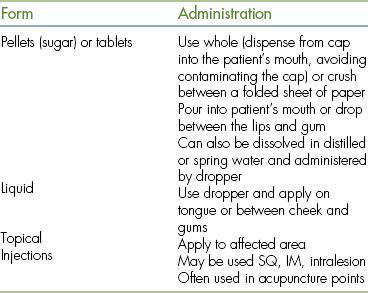

The remedies are fragile compared with Western medications. There are several forms (Figure 23-2). They should not be touched and should be administered away from food, whenever possible. The remedy is effective as soon as it gets into the mouth; as long as it touches the lips, gums, or tongue, it does not need to be swallowed. Remedies should never be returned to the bottle. They should be stored at room temperature away from moisture (keep container sealed) in a dark place, preferably in a cabinet away from strong herbs, Western medication, and magnetic fields (microwaves, computers, stereo speakers) (Table 23-6).

FIGURE 23-2 Homeopathic preparations: clockwise, left to right: tablets, ointment, injectable (foreground), pellets, liquid (flower essence).

Homeopaths believe that things that suppress symptoms actually drive disease deeper into the body, or create more imbalance. Depending on how “deep” or serious the disorder is, it may take a succession of several remedies to restore a patient to health. Changes in symptoms are noted, and a new remedy is chosen until the patient is healthy.

Homeopathy can be used at many levels. The least complex is the treatment of acute disease, which should quickly restore health to a vital, strong patient. An example of this is the use of Arnica montana to treat a patient with bruising from trauma. Several remedies are fairly easily used in acute situations, even without extensive training (Table 23-7). Next is treatment on a constitutional level, which takes into account the nature (physical traits, personality, emotions) of the patient and “disease” symptoms, past and present. The goal is to help the patient restore and maintain a state of health. The most complex is miasmic treatment, in which the ultimate goal of therapy is to prevent disease by addressing genetic weaknesses. This is quite challenging in the veterinary patient and is therefore not often undertaken.

TABLE 23-7

Commonly Used Single Homeopathic Remedies for Acute Use

| Remedy | Symptoms |

| Arnica | Bruising, bleeding |

| Calendula | Topical for skin irritation |

| Ledum | Hives, stings |

| Nux Vomica | Vomiting |

| Pulsatilla | Purulent discharge |

| Thuja | Vaccine reaction |

Homeopathy can be further divided into classical homeopathy, in which the patient is treated with one remedy at a time, and modern homeopathy, in which the patient is given a combination of remedies to match his or her given set of symptoms. Homotoxicology is the most commonly used form of combination homeopathy in veterinary medicine. The remedies are compounded using the most commonly indicated remedies used to treat a specific set of symptoms, such as low back pain. This therefore alleviates the need to repertorize and choose one remedy (Table 23-8).

TABLE 23-8

Commonly Used Homotoxicology Products and Their Indications

| Product | Indications | Main Ingredients |

| Discus Compositum | Sciatica, hind limb weakness | Berberis, cimifuga, colocynthis |

| Spascupreel | Muscle spasm | Aconitum, colocynthis, atropinum |

| Traumeel | Inflammation, pain | Arnica, aconitum, belladonna |

| Vertigoheel | Vestibular issues | Cocculus, coneum |

| Zeel | Arthritis | Silicea, arnica, rhus tox |

The combination therapy can be used in a more “Western” approach. For example, Traumeel (see Figure 23-2) is a commonly used treatment for bruising, trauma, inflammation, and arthritis. It comes in several forms (oral tablets and liquid, injectable, and cream) and contains arnica, calendula, echinacea, and several other individual remedies that work together to provide the desired effect.

From a scientific standpoint, there has been much research on homeopathy. The individualized nature of the treatments can make it difficult to “prove” from a Western standpoint, but many double-blind placebo-controlled studies exist. Research on the biphasic nature of medication has assisted our understanding of how diluted forms of medication can have the opposite effect of the therapeutic dose of the same medicine on the body. For example, a clinical dose of atropine causes drying of mucous membranes, but a tiny dose has been shown to increase secretions of mucous membranes. Both in vitro and clinical studies have shown homeopathic remedies to be effective, but thus far we do not understand exactly how they work.

FLOWER ESSENCES

Flower essence therapy, developed by Edward Bach in the 1930s, uses an approach similar to homeopathy to treat patients. Bach believed that all substances used to treat patients should be completely nontoxic, even in undiluted form. He developed 37 essences derived from plants (flowers, bushes, trees) and one from water (rock water) for a total of 38 remedies (Table 23-9). These essences are not diluted to the extent that homeopathic remedies are.

TABLE 23-9

Basic Flower Essences and Their Uses

| Essence | Indications |

| Rescue Remedy | Shock, trauma, stress |

| Cherry plum | Panic, loss of control |

| Clematis | Lack of responsiveness |

| Impatiens | Impatience, irritability |

| Rock rose | Extreme fear |

| Star of Bethlehem | Shock, trauma |

| Agrimony | Prolonged grief, moping and withdrawing |

| Aspen | Fear of unknown things (strangers) |

| Beech | Intolerance, rigidness |

| Centaury | Submissiveness, timidness |

| Cerato | Indecisiveness (need constant reassurance) |

| Chestnut bud | Repetitive actions (helps break bad habits) |

| Chicory | Possessiveness (separation anxiety) |

| Crab apple | Detoxification |

| Elm | Overwhelming stress of (working, competing, travel) |

| Gentian | Depression |

| Gorse | Hopelessness |

| Heather | Attention-seeking behavior (constant barking, whining) |

| Holly | Jealousy, especially when aggressive or spiteful |

| Honeysuckle | Grief, homesickness |

| Hornbeam | Helps adjust to changes |

| Larch | Lack of confidence |

| Mimulus | Fear of known things (thunderstorms) |

| Mustard | Mood swings, depression, gloom |

| Oak | Workaholic (overworks to exhaustion) |

| Olive | Lack of energy, exhaustion |

| Pine | Excessive grief, rejection, guilt |

| Red chestnut | Worry, overprotectiveness |

| Rock water | Inflexibility |

| Scleranthus | Indecision with mood swings, motion sickness |

| Sweet chestnut | Extreme stress, mental anguish |

| Vervain | Excessive enthusiasm, hyperactivity |

| Vine | Aggression, dominance |

| Walnut | Stress as a result of change |

| Water violet | Aloofness, withdrawal |

| White chestnut | Restlessness, repetitive thoughts |

| Wild oat | Frustration, boredom, lack of concentration |

| Wild rose | Apathy, resignation |

| Willow | Resentment, sulkiness |

The use of flower essences is based more on a psychologic or emotional than physical level. Bach himself described 12 pathologic emotional states that he believed would lead to physical disease if left untreated. For example, the remedy Aspen is used to treat patients with fear of the unknown, and holly is used to treat patients exhibiting jealousy or suspiciousness. Of course, the emotional nature of animals can be difficult to determine, but it is not unreasonable and can be quite rewarding. Flower essences may, like homeopathy, be used in acute situations in addition to treating patients on a constitutional basis.

The individual essences are all provided as a liquid. The most common remedy used is called Rescue Remedy (see Figure 23-2), and it is a combination of five flower essences (rock rose, cherry plum, star of Bethlehem, clematis, impatiens). The preparation may also be found in a cream. It is used to treat animals in times of stress, anxiety, or trauma. For those interested in using flower essences, Rescue Remedy is an excellent starting point and can be used in such situations as trauma, surgery recovery, or even for the frightened and panic-stricken boarding patient. The remedies are administered like homeopathic remedies, but they are generally sold in stock bottles. The stock flower remedy should be diluted in spring water or a combination of water and alcohol (increases shelf life) to make a treatment bottle. Generally, 2 drops of each stock remedy (four if using Rescue Remedy) are placed in a 1-oz glass amber vial with a dropper. Up to five remedies may be combined in one treatment bottle (Rescue Remedy only counts as a single remedy). They are given by the dropper directly into the mouth. They may also be added to drinking water (from a few drops in a bowl for a cat to 15 drops per gallon for a horse). Another method is using the remedy in a spray bottle as a mist (usually into the environment), which is an effective and stress-free means of treating birds and small mammals. It can also be used topically. Administration is generally repeated at various intervals. In an acute situation, it may be as often as every 30 seconds. For a less urgent situation, it may be daily for several days or weeks. Flower essences should be stored like homeopathic remedies.

These flower remedies, like their homeopathic counterparts, are safe to use and can have a profound effect on a patient when the correct remedy is given. They are often used as an adjunct to other therapies that do not do as much to address the emotional aspect of healing. As you can imagine, the technician can be of great value to the veterinarian who practices homeopathy. By assisting in observation of the patient and clients’ education, the technician can have a substantial impact on the success of the treatment.

APPLIED KINESIOLOGY

Applied kinesiology (AK) is an approach to health care that uses functional assessment measures, such as posture and gait analysis, manual muscle testing as a functional neurologic evaluation, range of motion, static palpation, and motion analysis to diagnose patients. These assessments are used in conjunction with standard methods of diagnosis, such as clinical history, physical examination findings, and laboratory tests to develop a clinical impression of the unique physiologic condition of each patient. Thousands of professionals belong to the International College of Applied Kinesiology (ICAK), including chiropractors, physicians, osteopaths, dentists, podiatrists, psychologists, and veterinarians. More than 2100 clinical research papers have been published by the ICAK. Veterinarians take a basic 100-hour certification course through the ICAK.

George Goodheart, D.C., is recognized as the creator of the field of AK. As early as 1964, he recognized that dysfunction of the muscle and tendon receptors in a particular muscle could affect the strength of that muscle and have a negative effect on the stability of a related joint. Whereas most practitioners were treating musculoskeletal problems by addressing the hypertonic muscles, Dr. Goodheart saw that most of the time the problems were related to muscle paresis. He came to discover, and has since been supported by research, that muscle weakness could be caused by a large number of factors affecting output from the ventral horn. Dr. Goodheart investigated the effects of many different types of existing techniques on the efficiency of muscle function. These include the following techniques and relationships:

• Chapman’s reflexes, which are known in AK as neurolymphatic reflexes

• Bennett’s reflexes, which are known in AK as neurovascular reflexes

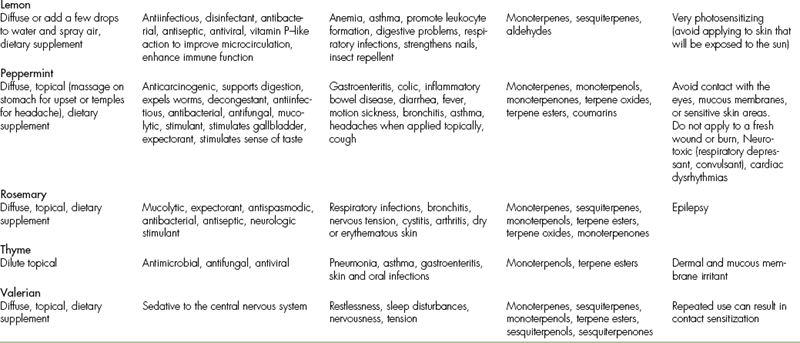

One of the tools in AK is manual muscle testing for functional neurologic assessment. It can be used to evaluate and correct functional imbalances in the structural, chemical, mental, and energetic systems of the patient. It is important to note that manual muscle testing is only a small part of AK, and these terms are not mutually interchangeable. In muscle testing, the professional places pressure against a certain muscle, and the patient tries to resist the motion caused by this pressure. For example, if one person held an arm out to their side parallel to the ground, the major muscle holding it there would be the deltoid muscle. If the professional put pressure downward and the deltoid muscle was weak, the arm would go down relatively easily. If the deltoid muscle was strong, it would take a much greater force to bring the arm down. The physician using AK finds a muscle that is unbalanced and attempts to determine why that muscle is not functioning properly. This may be due to improper facilitation or neuromuscular inhibition. On the basis of response to therapy, it appears that in some of these conditions, the primary dysfunction is due to deafferentation, the loss of normal sensory stimulation of neurons as a result of the functional interruption of afferent receptors. It may occur under many circumstances, but is best understood by the concept that with abnormal joint function (subluxation or fixation), the uncharacteristic movement causes improper stimulation of the local joint and muscle receptors. This changes the transmission from these receptors through the peripheral nerves to the spinal cord, brainstem, cerebellum, cortex, and then to the effectors from their normally expected stimulation. Symptoms of deafferentation arise from numerous levels, such as motor, sensory, autonomic, and consciousness, or from anywhere throughout the neuraxis. The physician works out the treatment that will best balance the patient’s muscles. Treatments may involve specific joint manipulation or mobilization, various myofascial therapies, cranial techniques, meridian and acupuncture skills, clinical nutrition, dietary management, evaluating environmental irritants, and various reflex procedures. In human medicine, the application of AK diagnosis requires that the physician be competent in the testing of all accessible muscles of the body. In animal AK, the insertion of a surrogate tester reduces the number of muscles tested to one or two. It is hard to tell an animal to resist a given motion; this is where the veterinary technician plays a role. They are the missing link of the animal manual muscle test. The technician’s role is to be a surrogate, adding another human being to the equation (Figure 23-3). When muscle testing adult humans, we test their muscles directly. It was discovered early on in AK that babies and quadriplegics could be tested indirectly by having a third person touch them while the physician tested the surrogate’s muscle for changes in strength. The same tests or challenges are applied to the patient, but the muscle testing response is through the surrogate. This same principle has been applied with great success to animals. How surrogate testing works is not really known at this time. It is hypothesized that neurologic information, which is conveyed electrically, is transferred to the mostly salt and water surrogate by contact with the patient.

The technician is an important team member in a practice that uses AK. The involvement may include writing down examination findings and treated areas and assisting with restraint and communication with clients. The technician should have a basic knowledge of the procedure and what abbreviations or AK notations are used at the practice.

ACUPUNCTURE

The term acupuncture comes from the Latin words acus, meaning “needle,” and pungere, meaning, “to pierce.” It is the technique of piercing the skin with a needle at specific, predetermined “acupuncture points.” It is now known that these points can be stimulated by more than just needles; they can also be stimulated by injection of fluid, laser, ultrasound, surgically implanted material, and electrical stimulation.

Acupuncture has been used for more than 4000 years in the East as one medical method within TCM. TCM is a system of medicine that includes herbology, massage, and nutritional and lifestyle management. Early Chinese veterinary applications of acupuncture started with the domestication of animals. Veterinary acupuncture came to the United States in the early 1970s, and in 1974 the International Veterinary Acupuncture Society (IVAS) was organized with the aim of fully integrating acupuncture into Western veterinary science. Acupuncture is used to treat all species from ferrets and birds to dogs and cattle to elephants and killer whales.

In the United States, acupuncture is increasingly used as a modality in the treatment of musculoskeletal, neurologic, cardiovascular, respiratory, GI, reproductive, and dermatologic disorders. Although it has the ability to help many areas of the body, pain management is probably the most common use of acupuncture today.

TERMINOLOGY AND RECORD KEEPING

Acupuncture points are connected through pathways that are called meridians or channels. In TCM, it is believed that the body’s vital energy or life force (bioelectricity) circulates in a cyclic predetermined course through the meridians. In most species, there are 14 classical meridians: 12 are associated with specific organ systems on which they have a primary influence, and two run on the midlines of the body. The paired organ-related meridians are named lung (LU), large intestine (LI), stomach (ST), spleen (SP), heart (HT), small intestine (SI), bladder (BL), kidney (KI), pericardium (PC), triple heater (TH), gallbladder (GB), and liver (LV). The unpaired channels are conception vessel (CV) that runs on the ventral midline and the governing vessel (GV) that runs on the dorsal midline. Individual acupuncture points are named and recorded by pairing the meridian and a number (e.g., LV3 is the third point on the liver meridian, and SP6 is the sixth point on the spleen meridian). In addition, there are “extra” points that do not lie on meridians and trigger points, which are temporary tender areas that can move on and off the meridians in episodes of pathologic conditions.

ACUPUNCTURE THEORIES

According to TCM theory, energy circulates through each meridian every 24 hours. The meridians run on the surface of the body, where acupuncture points can be accessed and manipulated. A blockage of energy circulation manifests as dysfunction or disease. Medical conditions that can be helped result from stagnant energy circulation or lack of sufficient energy to function optimally. Stagnant energy manifests as painful spasms or swelling, whereas deficient energy manifests as atrophy or weakness. To bring the body into balance and to facilitate healing, it is necessary to stimulate or sedate energy levels at acupuncture points. There are many theories about how acupuncture works. The most current acupuncture theories discussed in the human literature are as follows:

THE GATE THEORY

The gate theory explains the analgesic effects of acupuncture. It has been shown that different types of neurons transmit pain. When an acupuncture needle is inserted, thin myelinated nerve fibers carry a message to the spinal cord. The neurotransmitters are released and taken up by the interneurons. When the impulse from the unmyelinated pain nerve fibers causes the release of neurotransmitters, the receptors are full and the “gate” is closed to that signal with little to no message of pain reaching the brain.

ENDOGENOUS OPIOID THEORY

Opioids have been used for many years to combat pain (i.e., poppy, morphine, torbutrol). Depending on where the needles are placed, acupuncture has been shown to release β-endorphins, met-enkephalins, and leu-enkephalins in both the blood and cerebral spinal fluid. These endogenous opioids can be reversed with naloxone (an injectable agent used in veterinary medicine to reverse the effects of morphine). Opiates are also known to have systemic effects that can be produced by acupuncture. For example, opiate receptors in the gut are responsible for decreasing peristalsis and increasing segmental contractions, thus effectively controlling diarrhea.

AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM THEORY

This theory looks at how needles inserted into the skin can have an effect on the muscles and organs of the body. Numerous viscerosomatic (relating the organs to the muscles) relationships have been studied, and it has been found that visceral and somatic fibers have adjacent tracts in the spinal cord and distribution in the dorsal gray matter. Examples of this relationship include muscle cramping seen secondary to inflammation of the intestines and the phenomenon of “referred pain,” which is when there is pain felt in one part of the body but it is different from the part of the body that was stimulated.

HUMORAL THEORY

This theory was first postulated after studies showed that a transfer of blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), or brain tissue from an animal under acupuncture analgesia to an animal not receiving acupuncture resulted in analgesia of the recipient. This analgesia was generalized and reversed by naloxone. β-endorphins are released by acupuncture and may contribute to analgesia, but it is not the only important component. Serotonin is also important and increases 30% to 40% in the systemic circulation after acupuncture. Acupuncture has also been shown to cause systemic increases in growth hormone, prolactin, oxytocin, luteinizing hormone, white blood cells, immunoglobulins, antibodies, and interferons, depending on which points are stimulated.

BIOELECTRIC THEORY

Becker and Reichmanis, in 1976, proposed a theory that the healing and analgesic properties of acupuncture are based on a direct current (DC) system. In this system, electric signals are generated and propagated by Schwann cells, satellite cells, and glial cells. Acupuncture points, like amplifiers, would boost the DC signal along the nerve pathways. The insertion of a metal acupuncture needle would, in effect, short-circuit the system and block pain perception. In this system, acupuncture points boost the DC signal along the meridian, comparable with an amplifier boosting electricity along a high-power tension wire.

TECHNIQUES

Dry needling is performed using stainless steel acupuncture needles (Figure 23-4). These needles are 25 to 36 gauge and range from ½ to 2 inches long when used with companion animals or up to 4 inches long when used with large animals. Large animal practitioners will often use hypodermic needles in their patients.

Moxibustion is the burning of dried leaves of the Artemisia vulgaris or mugwort plant. The moxa stick can be moved slowly over an acupuncture point or be placed on an inserted needle. This is often used for animals with degenerative changes that do better in warm dry climates than when it is cold or damp. In TCM, this adds energy to a deficient area.

Aquapuncture is the injection of a solution into an acupuncture point. The most commonly used substance is vitamin B12, although electrolyte solutions, saline, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), vitamin C, antibiotics, herbal extracts, homeopathics, and local anesthetics can be used. It is thought that either the pressure on the point or the solution itself will stimulate the nerve fibers.

Electroacupuncture is the passing of electrical energy through acupuncture points. Stimulation is accomplished by connecting an electronic device to the inserted needles. Indications include paralysis or paresis, severe and chronic painful conditions, or conditions not responsive to dry needling.

To achieve a continuous stimulation of an acupuncture point, various materials may be surgically implanted at acupuncture points, called implantation. Though catgut, stainless steel, and silver can be used, the most common implant is gold in the form of solid beads or wires. This technique is most commonly used for young dogs with painful hip dysplasia, older dogs with coxofemoral arthritis, or epilepsy. This is considered a surgical procedure.

Low-intensity or “cold” lasers have been used to stimulate acupuncture points. Laser puncture is a noninvasive form of intense light therapy using various frequencies and wavelengths that promote positive physiologic changes within cells. It is used to (1) stimulate acupuncture points, (2) enhance healing of wounds and burns, and (3) treat acutely inflamed joints (Figure 23-5).

FIGURE 23-5 Laser acupuncture: Laser acupuncture can be used for painful or swollen areas or with animals that are sensitive to needling.

Ultrasound can be used to stimulate an acupuncture point, but it is not commonly done, perhaps because of the cost and also the necessity of shaving at each acupuncture point.

Microcurrent therapy is the use of a machine that generates a microcurrent of electricity that can be used on acupuncture points or directly over areas of pain or muscle spasm.

Acupuncture needles can be placed in the tissue perpendicularly or at an angle. When removing the needles, they should be gently pulled in the same direction that they went in. If there is resistance when removing the needle, tapping around the needle, rolling it back and forth, or gently holding down the skin on either side of the needle while pulling the needle gently will ease if from the tissue. Occasionally the needles will come out crooked, which is not unusual because they bend easily. All needles should be accounted for and placed into a sharps container.

The technician’s role in acupuncture includes having a general understanding of how and why acupuncture works to be able to discuss it with clients; charting the points in the record; aiding if patient restraint or diversion is needed; assisting in easing a patient’s anxiety, if present; and removing and counting the needles.

PHYSICAL MODAILITES

Massage is defined as a systematic and scientific manipulation of the soft tissues of the body for the purpose of obtaining or maintaining health. Massage has been performed for thousands of years. There are more than 70 types of human massage philosophies, many of which can be applied to animals.

Types

Shiatsu is a Japanese form of massage that literally means “finger pressure.” Shiatsu practitioners use finger pressure on specific points in the body (correlating to acupuncture points) to increase circulation and stimulate the nervous system.

In trigger-point massage, or myotherapy, the therapist feels for taut bands or knots that have a point of maximal tenderness. Pressure on this point can cause local pain, referred pain, and muscle spasms in humans and animals. The manual technique for deactivating a trigger point is ischemic compression. By applying direct pressure over the point, the tissue becomes ischemic (blood is pushed out of the tissue), and when the pressure is removed, the tissue becomes hyperemic (blood quickly infiltrates the tissue). This will often relieve the tension, band, or knot, and the pain. This pressure is usually held for 8 to 15 seconds, and if a spasm is felt during the pressure, it should be maintained until the muscle stops firing.

Sports massage can be broken into event massage and maintenance massage. Event massage (relating to a massage done on an athlete before, during, or after competing) can be broken down into preevent, interevent, and postevent. The goal of preevent massage is to leave the animal relaxed and ready for the event. Interevent massage keeps the patient tuned up and ready for the next event, and postevent massage flushes out metabolic waste and reduces muscle spasms and soreness. The goal of maintenance massage is to help prevent injury and expedite the healing of injured tissue.

TTEAM is a system of massage for teaching physical awareness of the body. Originally designed for horses, and based on the human work of Dr. Feldenkrais, TTEAM is a form of massage that is devoted to nonhabitual motion to reeducate the nervous and musculoskeletal systems. It has an impact on an emotional level in addition to aiding focus, coordination, and balance. A major difference between TTEAM and other forms of massage is that whereas massage works on the deeper tissue, TTEAM manipulates only the skin. Although this was originally designed for horses, all species may benefit from this therapy.

Swedish massage is the most commonly used massage system in North America. These techniques began in the late 1700s and will be discussed for use on animals. Studies have shown that massage is beneficial in reducing stress, enhancing blood and lymph circulation, decreasing pain, promoting sleep, reducing swelling, enhancing relaxation, and increasing oxygen capacity of the blood.

Techniques

Effleurage is the most commonly used stroke in animals. It is a gliding stroke that follows the contour of the body. Hand over hand, thumb over thumb, or one hand on either side of the body are the most common variations. It is repeated several times at the beginning and end of the massage to evaluate the tissue and enhance blood flow (warm it up and then aid in flushing lactic acid). Animals usually prefer these stokes flowing with the hair. Although effleurage is often thought of as a light stroke, deeper strokes are used to lengthen muscles and aid in stretching.

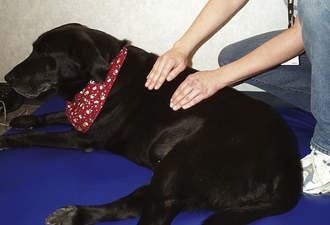

Pétrissage, or kneading, consists of rhythmic lifting, squeezing, and releasing the tissue. It assists in removing metabolic waste and increasing circulation. The hands form a C shape and can be alternated in a circular motion, can “roll” the skin, or can spread up and out to help widen or broaden the muscle (Figure 23-6).

FIGURE 23-6 Pétrissage: Bandit receiving pétrissage, notice the “C” shape to the hands and the alternating pattern to the hands.

Friction is the manipulation of tissue to increase circulation. It is commonly used over tendons when tendinitis is present, over knots and trigger points, and over joint capsules with excessive fibrous tissue. It is also used to break up skin adhesions and scar tissue (wait 3 to 4 weeks after injury or surgery before applying this technique). When applying this to deep tissue, one finger or thumb is placed on the skin and either rubs the skin or is attached to the skin and rubs the tissue underneath. This can be done longitudinally (with muscle fibers), cross fiber (perpendicular to the muscle fibers), circularly, diagonally, or in a J pattern.

Tapotement is a tapping motion of the hands or fingers. When done for a short time, it stimulates nerve endings (preevent sports massage or to tone atrophied muscles). When done longer, it has a more sedative effect. Coupage, which is used to loosen phlegm congestion in the lungs, is a form of tapotement. The hands are cupped, and the strokes start at the caudal aspect of the ribs and move forward. Proper positioning using wedges or pillows can help maximize the effectiveness of coupage. This stroke may be continued for 5 to 10 minutes on each side (Figure 23-7).

FIGURE 23-7 Tapotement: Coupage, a form of tapotement, is performed on Shadow. Note that the hands are cupped and alternating. The motion starts at the base of the ribs and moves forward.

Vibration is a rapid shaking or slower rocking of the tissue. The speed of vibration will affect outcome: faster vibration will be stimulatory, whereas slower speeds will be inhibitory. It differs from tapotement in that the therapist’s hands do not leave the patient’s skin. It can aid in relaxing muscles, reducing trigger-point activity, and when used over a joint capsule in the proper position can act as a joint mobilization.

Swedish Massage

Swedish massage breaks down the massage into several elements. The elements include intention, touch, pressure and depth, excursion, speed, rhythm and continuity, duration, and sequence. Intention is the consciously sought out goal of the therapist. Therefore the massage outcome is different if the therapist wants to create relaxation versus invigoration. Touch is the vehicle of massage and conveys the intention. Pressure is the force applied to the surface, usually through the therapist’s hands. Depth is the distance traveled into the patient’s tissue. The therapist controls the force, but the patient has more control over the depth. Often, applying less pressure slowly will increase depth, whereas fast, higher pressure will cause splinting (muscle contracting in a protective reflex) to occur. Excursion is the length of one massage stroke. In a cross-friction massage, meant to relieve tendinitis, the excursion may be only 1 to 2 cm, but in a beginning effleurage stroke, the excursion may be from the head all the way to the tip of the tail. Speed refers to how fast the hand moves over the patient. In an invigorating preevent sports massage, the speed will be much faster than if the therapist’s goal is to achieve relaxation. The repetition or regularity of the stroke defines its rhythm, similar to music. The concept of continuity in massage refers to the uninterrupted flow of strokes and to the unbroken transition from one stroke to the next. It is hard for the patient to relax if the rhythm is not smooth or if the continuity is not fluid. Duration is the length of time devoted to one area. In humans, a relaxing massage does not usually last more then 1 hour without creating muscle soreness. The duration of a small animal massage is usually 30 minutes, and for a large animal, like the human, it is approximately 1 hour. A sequence is the arrangement of the massage strokes.

A typical example of a sequence would be:

• Start with effleurage on the face and head.

• Continue down the back and sides.

• Use pétrissage over the paraspinal muscles (including kneading, circles, or strokes going with or perpendicular to the muscle fibers).

• Apply ischemic compression on trigger points if found.

• Move on to one side of the neck.

• Perform effleurage, with strokes running from the toes to the heart to flush toxins.

• Continue by using skin rolls along the body wall.

• Apply the same techniques you used in the forelimb to treat the rear limb.

• Gently flip the patient over if a canine or walk around to the other side if an equine.

Signs of relaxation include sighing, yawning, licking the lips, hanging the head (equine), burping, or flatulence. Signs that the pressure is too great include increased respiratory rate, opening the eyes (if previously closed), fidgeting, and incessant licking (canine) or swishing the tail (equine).

Contraindication

There are several contraindications to massage, and there are also endangerment sites. Endangerment sites are areas of the body that are delicate and are relatively unprotected. Contraindications include massage over bacterially or virally infected lesions, over open wounds, over the area of an acute injury or inflammatory condition, over an area of hemorrhage, or following a recent high fever. Some endangerment sites include the throat, eyeballs, brachial plexus, abdomen (deep, near the aorta), and over the kidneys.

Precautions should be taken when massaging a patient with heart disease or over a neoplastic area.

VETERINARY CHIROPRACTIC

Chiropractic is perhaps one of the most familiar and most used complementary therapies that are used to treat veterinary patients. The term is derived from the Greek cheir (“hand”) and praxis (“practice”). The purpose of chiropractic is to manually restore reduced motion in the spine and limbs, thereby improving patient mobility, comfort, and in many cases nervous system function. A. E. Homewood defined chiropractic as “that science and art which uses the inherent recuperative powers of the body and deals with the relationship between the nervous system and the spinal column, including its immediate articulations, and the role of this relationship in the restoration and maintenance of health.”

The technician is an important team member in a practice that uses chiropractic. The involvement may include writing down examination findings and treated areas and assisting with restraint and communication with the client. The technician should have a basic understanding of the procedure, be able to properly stabilize an area to facilitate adjustment, and be familiar with what abbreviations or chiropractic notations are used at the practice.

The technician should have a basic knowledge of the procedure and what abbreviations or chiropractic notations are used at the practice.

History

Manipulation of the spine is an ancient practice. References were made to this form of treatment as early as 2700 bc in China. Even Hippocrates noted the effects of this type of therapy because he notes, “Look well to the spine for the cause of disease.” Chiropractic began in the United States in 1895 with D. D. Palmer who began to treat the spine as a primary method of healing his patients. His son, B. J. Palmer, followed in his father’s footsteps and further developed chiropractic into a system of medicine. He founded the first school of chiropractic in Davenport, Iowa. He claimed to have treated animal patients and people in his hospital at the school.

Chiropractic is becoming a more accepted and mainstream treatment in humans. Most major health insurance carriers now cover chiropractic care. This increased accessibility to people has contributed significantly to the increased demand for chiropractic care for veterinary patients. Also contributing to a wider acceptance is the growing amount of research that has been done on chiropractic in humans. Many of these same studies use animals as models for human disease, thus creating even more applicable research for veterinarians.

In most states, veterinary chiropractic adjustments must be performed by a trained professional (either a veterinarian or a chiropractor). Training leading to certification in veterinary chiropractic is available to both groups of professionals through postgraduate courses, but it is not yet a part of standard or elective coursework in either profession.

In the United States, certification is available to both groups of professionals through the American Veterinary Chiropractic Association (AVCA), which was founded in the 1980s. This involves approved coursework (consisting of at least 200 hours of lecture and hands-on labs), a certification examination (written and practical), and completion of several case reports. To remain certified, a veterinarian must complete 30 hours of continuing education every 3 years.

Philosophy and Theory

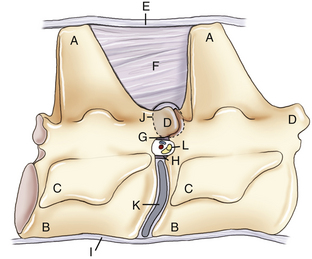

Chiropractic is much more than the stereotyped “bone out of place.” A chiropractic problem, known as a subluxation or vertebral subluxation complex (VSC), involves an abnormal relationship between two adjacent vertebrae. This is an anatomically complex area known as the motor unit (Figure 23-8). It consists of muscles, ligaments, connective tissue, a spinal nerve and other smaller nerves, blood vessels, lymphatics, and CSF. The hallmark, or “triad” of signs that occur with a subluxation, includes altered mobility, pain on palpation, and abnormal tension in the surrounding (paraspinal) muscles.

FIGURE 23-8 The motor unit is a complex anatomic and dynamic area that consists of two adjacent vertebrae and the tissues in between. A, Dorsal spinous process; B, vertebral body; C, transverse process; D, articular facet joint; E, supraspinous ligament; F, interspinous ligament; G, ligamentum flavum; H, dorsal longitudinal ligament; I, ventral longitudinal ligament; J, joint capsule; K, intervertebral disk; L, intervertebral foramen.

There are many explanations about how subluxations occur that have been validated by scientific research. The causes of subluxation can vary from overt trauma to minute repetitive stress to the area, such as abnormal spinal movement secondary to left forelimb lameness. Clinical signs range from mild discomfort to reduced reflexes to serious organ dysfunction. By determining where abnormal motion exists and correcting reduced motion in the spine, we can restore normal biomechanics to the body and reset normal neurologic pathways, thus aiding proper nervous system function. In addition, restoration of full motion in the joints of the limbs can be equally important to maintain spinal health because the body functions as a whole, and all segments are connected.

The chiropractic appointment begins with a clear and detailed history. Hopefully the patient has previously received a thorough “Western” medical work-up before the chiropractic appointment, but this is not always the case. The examination proceeds with observation of posture and gait, palpation of the spinal column and the extremities (limbs and tail), neurologic evaluation, and review of diagnostic images and lab work. It is as detailed (or more so) than a typical general physical examination. Problem areas are recorded, usually using AVCA’s notations. This creates a uniform way of communicating with other veterinarians who use chiropractic (much as abbreviations for a CBC or blood chemistry are universally understood).

Once the problem areas are identified, the veterinarian determines whether a chiropractic adjustment is an appropriate therapy for the patient at that time. Sometimes more diagnostics may be required, either in the future or before any adjustment is performed. For example, a horse may have neurologic deficits consistent with equine protozoal myelitis (EPM), and a spinal fluid analysis and EPM test may be indicated. A dog may be seen for lameness, and the veterinarian may find cranial drawer motion in the left stifle, indicating anterior cruciate ligament rupture. In both of these cases, chiropractic may help these patients and could be an appropriate therapy to perform at the initial visit, but other primary therapies are warranted. In some cases, such as when patients have acute paralysis secondary to intervertebral disk disease, it may be more appropriate to obtain further diagnostics (such as radiographs and a myelogram) before adjusting the patient to be sure that any areas of active disk disease are avoided.

The next step is for the veterinarian to adjust the patient. Although treatment principles are similar, each veterinarian has a unique technique that he or she has developed. The AVCA certifies veterinarians who are able to perform the basic techniques, but advanced techniques and variations may be learned. Often it is easiest to treat patients in a standing position (Figure 23-9). However, sometimes a sitting or sternal recumbent position may work better for small animal patients. Cats, in particular, are easier to treat while lying on the treatment table rather than being forced to stand. The best position for a patient is one that is comfortable for the patient.

FIGURE 23-9 Chiropractic adjustment: A technician uses food to gently restrain a patient in a standing position while the veterinarian performs an adjustment.

The veterinarian will check the motion between two spinal segments by applying pressure aligned with the way the joint surface glides. If reduced mobility is found in a given area, the veterinarian takes the motion as far as it will go and applies a short, quick motion in the plane of motion of the joint. Sometimes a popping noise (like someone cracking a knuckle) will accompany the adjustment, although this is more common in people than in animals. The adjustment should generally be painless for the patient, although sometimes a problem area may present some momentary mild discomfort. If a seriously painful area is found, the veterinarian will likely avoid treating that area altogether, at least until further diagnostics have been done. It is important to keep the patient relaxed and make the treatment a positive experience (both for the patient and the client), so all of the problem area may not be corrected in one visit. Following the treatment, the veterinarian will instruct the client on aftercare and follow-up visits in addition to any additional recommendations. Usually, there will be some period of rest or reduced exercise recommended, and massage and stretching may need to be done at home.

The Technician’s Role

Restraint is particularly important for the first-time patient because they are unsure about the process and may be nervous or frightened. Restraint can be simple, such as gentle petting, kind words, or a food distraction (see Figure 23-9). Often a patient may need to be repositioned so that the veterinarian is in the best position to perform the necessary adjustment. Most patients accept and enjoy the treatment, so generally, only gentle physical restraint is necessary. It may, however, be necessary to use more rigorous methods of restraint if the situation warrants. Some canine or feline patients may need to be muzzled (especially if they are regular patients at a general practice—they may be expecting a blood draw or a vaccine rather than a relaxing and comfortable treatment). Some horses will require twitching or hobbling, especially if they are not used to being routinely handled. In a large animal practice, sometimes the technician may be required to stabilize nearby segments so that an adjustment may be more effective or specific. Proper technique is required to provide the most effective treatment and for the assistant’s safety. Occasionally, although most veterinarians avoid it, chemical restraint is necessary for some patients to relax enough to receive a safe and effective treatment. This is much more likely to happen early in the treatment program, and most patients will not need to be sedated more than once or twice. The technician should become comfortable with all anticipated restraint techniques before their use because any unfamiliarity or nervousness may contribute to patient anxiety, and it is important for the patient to be as relaxed aspossible. Practicing on the staff’s pets is often a good method of developing proficiency in this important role.

In addition to restraining the patient, the technician may also be asked to stabilize certain areas of the spine for the veterinarian to effectively adjust a neighboring segment. This is especially true when assisting with large animals, such as horses. For example, when a veterinarian adjusts T6 in the horse, the technician must stand on the opposite side of the horse in a specific position (both body and hands) to stabilize T5 and T7.

Immediately after the treatment, the technician may be asked to massage the patient, apply essential oils, or walk the patient for several minutes to help the patient “hold” the adjustment. The day after the treatment, the technician may be responsible for making a follow-up telephone call, so it is important to be familiar with expected results and the veterinarian’s recommendations for aftercare. It is also helpful to be able to answer commonly asked questions about the examination, treatment, or aftercare. If there is a situation that deviates from the normal response, the veterinarian can be alerted, and the patient can be reevaluated in a timely fashion (Case Presentation 23-2).

PHYSICAL THERAPY AND REHABILITATION (SEE CHAPTER 24)

Physical therapy is a relatively new modality in both the human and animal realm. It has been used with horses and then companion animals for just more than 20 years, and although much has been learned, there is still much that we do not know. Physical therapy or rehabilitation is defined as the use of many modalities to relieve pain, build strength, and reeducate patients to walk in a balanced manner after an injury or illness. Many conditions benefit from physical rehabilitation. Passive range of motion, exercises, and cryotherapy and heat therapy will be touched on briefly, but will be discussed in more detail with all the other modalities of rehabilitation in Chapter 24.

PASSIVE RANGE OF MOTION

Passive range of motion (PROM) is the use of stretching to prevent the loss of normal range of motion, to return normal range of motion if absent, to increase cartilage nutrition in the joint, and to stimulate cartilage regeneration. Most of the nutrition received by the chondrocytes (cartilage cells) comes from the capillary-rich synovial capsule, which then bathes the cartilage via the synovial fluid. If the joint is stationary, the joint fluid is not circulated, and there is less nutrition available to the chondrocytes. In studies done in rabbits, after stabilizing a joint for 7 days, microscopic degenerative changes had already started in the cartilage.

If PROM is to be done postsurgically or in a joint with restricted motion, each joint that is stretched should be done separately. However, when PROM is performed on a patient with a neurologic disorder where it will be used to prevent loss of motion and increase cartilage nutrition and regeneration, each limb is done as a whole. The rules of PROM include:

2. If the patient is lying on his or her side, keep the limb that you are working on parallel to the ground to prevent torque of the joints.

3. Flex the most proximal joint first and work distally.

4. Do not let the stifle go under the rib cage.

5. Hold the limb flexed for 10 seconds, hold it in extension for 10 seconds (to the front, then 10 seconds to the back), and repeat this 10 times.

6. Massage the muscles you are stretching.

7. Guide the limb, do not pull it.

8. Do not hyperextend the carpus or tarsus because permanent tendon or ligament damage may occur. These joints are flexed and relaxed, unless there is a contracture issue involving these joints.

9. If it is postsurgical PROM, set up your hands on either side of the joint on which you are working (one joint is worked on at a time), and then move your eyes too and keep them on the surgery joint to prevent inadvertent motion of this joint.

10. The hip and shoulder joint have rotation and flexion and extension. Start with small circles and gradually increase the motion performing 10 rotations. Stabilize the distal joints.

The technician can take an active role in PROM, performing this modality under a veterinarian’s direction. This can be used successfully in equine and canine patients.

Exercises