Chapter 5 Recognizing Atelectasis

What is Atelectasis?

Common to all forms of atelectasis is a loss of volume in some or all of the lung, usually leading to increased density of the lung involved.

Common to all forms of atelectasis is a loss of volume in some or all of the lung, usually leading to increased density of the lung involved.

Unless mentioned otherwise, statements in this chapter that refer to “atelectasis” are referring to obstructive atelectasis. This might be a good time to review the chart from Chapter 4 (see Table 4-1) highlighting the markedly different appearances of the thorax in a large pneumothorax and atelectasis of the entire lung (see Fig. 4-2).

Unless mentioned otherwise, statements in this chapter that refer to “atelectasis” are referring to obstructive atelectasis. This might be a good time to review the chart from Chapter 4 (see Table 4-1) highlighting the markedly different appearances of the thorax in a large pneumothorax and atelectasis of the entire lung (see Fig. 4-2).Signs of Atelectasis

Displacement (shift) of the mobile structures of the thorax.

Displacement (shift) of the mobile structures of the thorax.

The right hemidiaphragm is almost always higher than the left by about half the interspace distance between two adjacent ribs. In about 10% of normal people, the left hemidiaphragm is higher than the right.

The right hemidiaphragm is almost always higher than the left by about half the interspace distance between two adjacent ribs. In about 10% of normal people, the left hemidiaphragm is higher than the right. In the presence of atelectasis, especially of the lower lobes, the hemidiaphragm on the affected side will usually be displaced upward (Fig. 5-5).

In the presence of atelectasis, especially of the lower lobes, the hemidiaphragm on the affected side will usually be displaced upward (Fig. 5-5). Overinflation of the unaffected ipsilateral lobes or the contralateral lung.

Overinflation of the unaffected ipsilateral lobes or the contralateral lung.

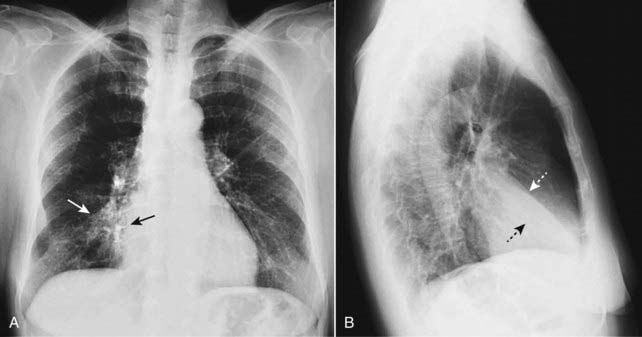

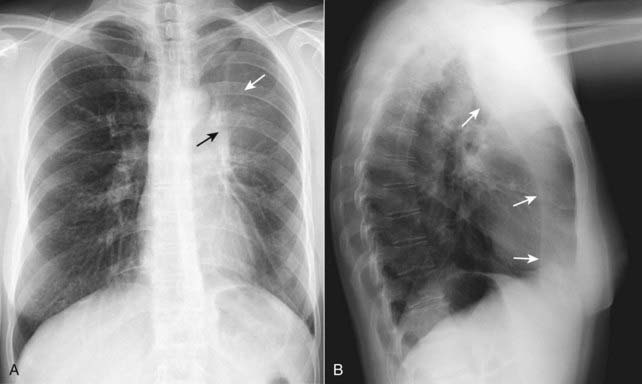

Figure 5-1 Right middle lobe atelectasis.

Frontal (A) and lateral (B) views of the chest show an area of increased density (solid white arrow), which is silhouetting the normal right heart border (solid black arrow) indicating its anterior location in the right middle lobe. On the lateral view (B), the minor fissure is displaced downward (dotted white arrow) and the major fissure is displaced slightly upward (dotted black arrow). Note the anterior location of the middle lobe.

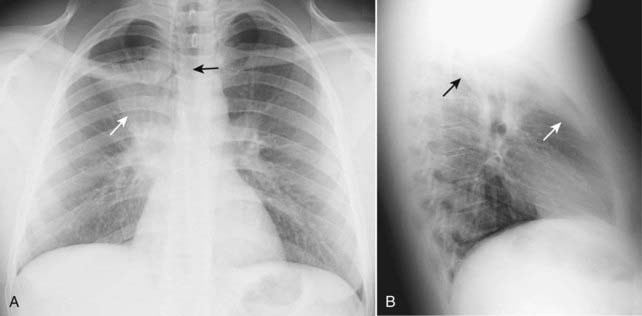

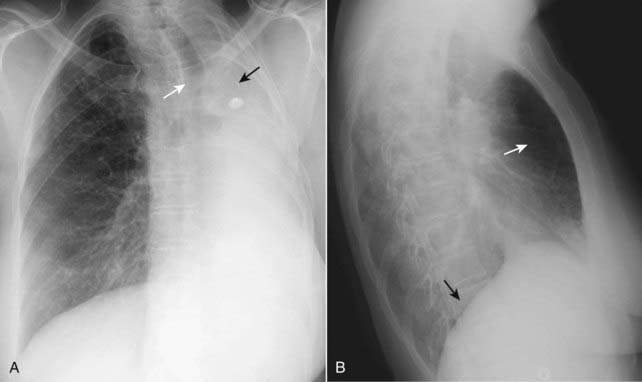

Figure 5-2 Right upper lobe atelectasis.

A fan-shaped area of increased density is seen on the frontal projection (A) representing the airless right upper lobe. The minor fissure is displaced upward (solid white arrow). The trachea is shifted to the right (solid black arrow). The lateral (B) demonstrates a similar wedge-shaped density near the apex of the lung. The minor fissure (solid white arrow) is pulled upward and the major fissure is pulled forward (solid black arrow). This is a child who had asthma leading to formation of a mucous plug, which obstructed the right upper lobe bronchus.

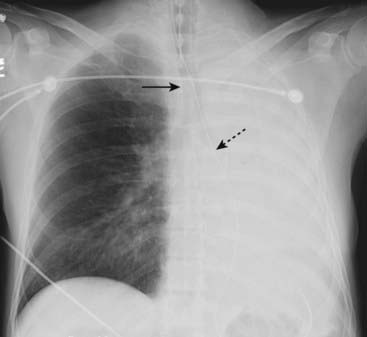

Figure 5-3 Atelectasis of the left lung.

There is complete opacification of the left hemithorax with shift of the trachea (solid black arrow) and the esophagus (marked here by a nasogastric tube, dotted black arrow) toward the side of the atelectasis. The right heart border, which should project about a centimeter to the right of the spine, has been pulled to the left side and is no longer visible. The patient had an obstructing bronchogenic carcinoma in the left main bronchus.

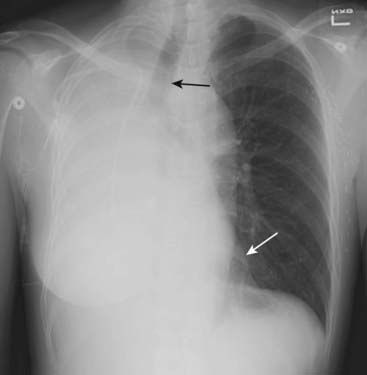

Figure 5-4 Atelectasis of the right lung.

There is complete opacification of the right hemithorax with shift of the trachea (solid black arrow) toward the side of the atelectasis. The left heart border is displaced far to the right and now almost overlaps the spine (solid white arrow). This patient had an endobronchial metastasis in the right main bronchus from her left-sided breast cancer. Did you notice the left breast was surgically absent?

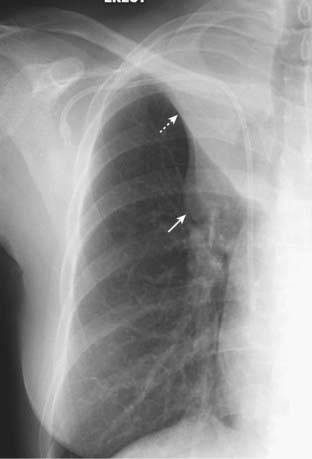

Figure 5-5 Left upper lobe atelectasis.

On the frontal projection (A), there is a hazy density surrounding the left hilum (solid white arrow) and there is a soft tissue mass in the left hilum (solid black arrow). Notice how the left hemidiaphragm has been pulled up to the same level as the right. The lateral projection (B) shows a bandlike zone of increased density (solid white arrows) representing the atelectatic left upper lobe sharply demarcated by the major fissure, which has been pulled anteriorly. The patient had a squamous cell carcinoma of the left upper lobe bronchus that was producing complete obstruction of that bronchus.

Figure 5-6 Left-sided pneumonectomy.

Complete opacification of the left hemithorax (A) is most likely from a fibrothorax produced following complete removal of the lung. There is associated marked volume loss with shift of the trachea to the left (solid white arrow). The left 5th rib was surgically removed during the pneumonectomy (solid black arrow). The right lung has herniated across the midline in an attempt to “fill-up” the left hemithorax, which is seen by the increased lucency behind the sternum in (B) (solid white arrow). Notice that because only the right hemithorax has an aerated lung remaining, only the right hemidiaphragm is visible on the lateral projection (solid black arrow). The left hemidiaphragm has been silhouetted by the airless hemithorax above it.

Types of Atelectasis

Subsegmental atelectasis (also called discoid atelectasis or platelike atelectasis) (Fig. 5-7)

Subsegmental atelectasis (also called discoid atelectasis or platelike atelectasis) (Fig. 5-7)

Compressive atelectasis

Compressive atelectasis

Figure 5-7 Subsegmental atelectasis.

Close-up view of the lung bases demonstrates several linear densities extending across all segments of the lower lobes, paralleling the diaphragm (solid black arrows). This is a characteristic appearance of subsegmental atelectasis, sometimes also called discoid atelectasis or platelike atelectasis. The patient was postoperative from abdominal surgery and was unable to take a deep breath. The atelectasis disappeared within a few days after surgery.

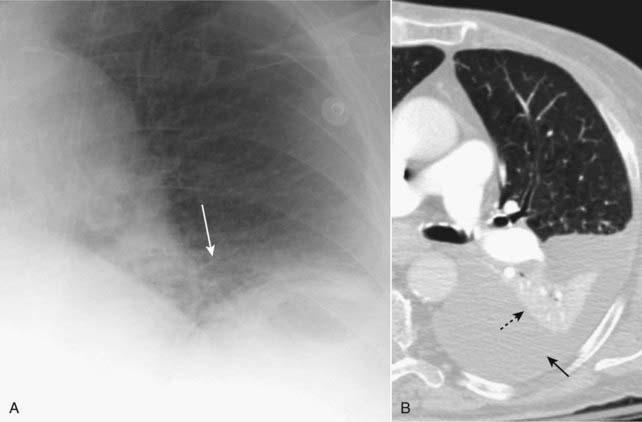

Figure 5-8 Compressive (passive) atelectasis.

Passive compression of the lung can occur either from a poor inspiratory effort (A), which is manifest as increased density at the lung bases (solid white arrow) or secondary to a large pleural effusion or pneumothorax (B). Axial CT scan of the chest showing only the left hemithorax (B) demonstrates a large left pleural effusion (solid black arrow). The left lower lobe (dotted black arrow) is atelectatic, having been compressed by the pleural fluid surrounding it.

![]() Pitfall: Be suspicious of compressive atelectasis if the patient has taken less than an 8 posterior-rib breath.

Pitfall: Be suspicious of compressive atelectasis if the patient has taken less than an 8 posterior-rib breath.

Obstructive atelectasis (see Fig. 5-3)

Obstructive atelectasis (see Fig. 5-3)

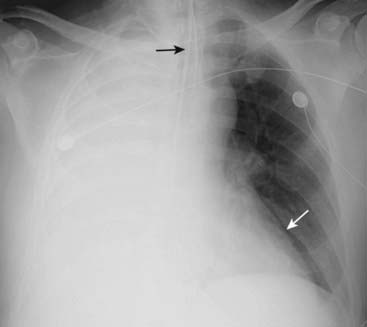

Figure 5-9 Atelectasis and effusion in balance, an ominous combination.

There is complete opacification of the right hemithorax. There are neither air bronchograms to suggest pneumonia nor any shift of the trachea (solid black arrow) or heart (solid white arrow). The absence of any shift suggests the possibility of atelectasis and pleural effusion in balance, a combination that should raise suspicion for a central bronchogenic carcinoma (producing obstructive atelectasis) with metastases (producing a large pleural effusion).

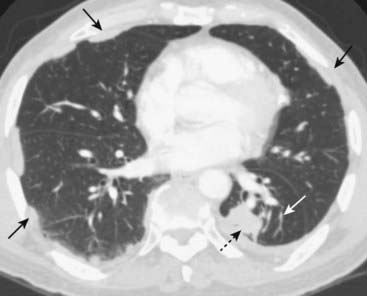

Figure 5-10 Round atelectasis, left lower lobe.

There is a masslike density in the left lower lobe (dotted black arrow). The patient has underlying pleural disease in the form of pleural plaques from asbestos exposure (solid black arrows). There are comet-tail shaped bronchovascular markings that emanate from the “mass” and extend back to the hilum (solid white arrow). This combination of findings is characteristic of round atelectasis and should not be mistaken for a tumor.

TABLE 5-1 TYPES OF ATELECTASIS

| Type | Associated With | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Subsegmental atelectasis | Splinting, especially in postoperative patients and those with pleuritic chest pain | May be related to deactivation of surfactant; does not usually lead to volume loss; disappears in days |

| Compressive atelectasis | Passive external compression of the lung from poor inspiration, pneumothorax, or pleural effusion | Volume loss of compressive atelectasis can balance volume increase from effusion or pneumothorax resulting in no shift; round atelectasis is a form of compressive atelectasis |

| Obstructive atelectasis | Obstruction of a bronchus from malignancy or mucus plugging | Visceral and parietal pleura maintain contact; mobile structures in the thorax are pulled toward the atelectasis |

Patterns of Collapse in Lobar Atelectasis

Obstructive atelectasis produces consistently recognizable patterns of collapse depending on the location of the atelectatic segment or lobe and the degree to which such factors as collateral airflow between lobes and obstructive pneumonia allow the affected lobe to collapse.

Obstructive atelectasis produces consistently recognizable patterns of collapse depending on the location of the atelectatic segment or lobe and the degree to which such factors as collateral airflow between lobes and obstructive pneumonia allow the affected lobe to collapse. In general, lobes collapse in a fanlike configuration with the base of the fan-shaped triangle anchored at the pleural surface and the apex of the triangle anchored at the hilum.

In general, lobes collapse in a fanlike configuration with the base of the fan-shaped triangle anchored at the pleural surface and the apex of the triangle anchored at the hilum. Other unaffected lobes will undergo compensatory hyperinflation in an attempt to “fill” the affected hemithorax, and this hyperinflation may limit the amount of shift of the mobile chest structures.

Other unaffected lobes will undergo compensatory hyperinflation in an attempt to “fill” the affected hemithorax, and this hyperinflation may limit the amount of shift of the mobile chest structures.

![]() Pitfall: The more atelectatic a lobe or segment becomes (that is, the smaller its volume), the less visible it becomes on the chest radiograph. This can lead to the false assumption of improvement when, in fact, the atelectasis is worsening.

Pitfall: The more atelectatic a lobe or segment becomes (that is, the smaller its volume), the less visible it becomes on the chest radiograph. This can lead to the false assumption of improvement when, in fact, the atelectasis is worsening.

Right upper lobe atelectasis (see Fig. 5-2)

Right upper lobe atelectasis (see Fig. 5-2)

Lower lobe atelectasis (Fig. 5-12)

Lower lobe atelectasis (Fig. 5-12)

Figure 5-11 Right upper lobe atelectasis and hilar mass: S sign of Golden.

There is a soft tissue mass in the right hilum (solid white arrow). There is opacification of the right upper lobe from atelectasis. The minor fissure is displaced upward toward the area of increased density (dotted white arrow), indicating right upper lobe volume loss. The shape of the curved edge formed by the mass and the elevated minor fissure is called the S sign of Golden. The patient had a large squamous cell carcinoma obstructing the right upper lobe bronchus.

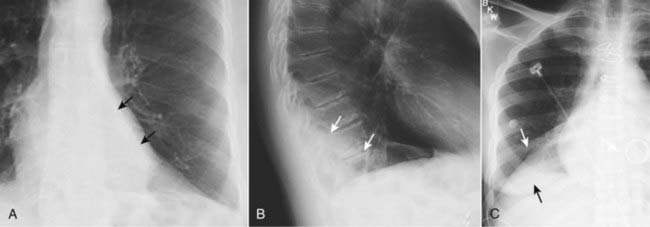

Figure 5-12 Left lower lobe and right lower lobe atelectasis.

A, A fan-shaped area of increased density behind the heart is sharply demarcated by the medially displaced major fissure (solid black arrows) representing the characteristic appearance of left lower lobe atelectasis. B, On the lateral view, the major fissure (solid white arrows) is displaced posteriorly. The small triangular density in the posterior costophrenic sulcus is in the characteristic location for left lower lobe atelectasis on the lateral projection. C, In a different patient there is a fan-shaped triangular density in the right lower lobe bounded superiorly by the major fissure (solid white arrow). Notice how the unaerated lower lobe silhouettes the right hemidiaphragm (solid black arrow).

![]() In the critically-ill patient, atelectasis occurs most frequently in the left lower lobe.

In the critically-ill patient, atelectasis occurs most frequently in the left lower lobe.

Right middle lobe atelectasis (see Fig. 5-1)

Right middle lobe atelectasis (see Fig. 5-1)

Endotracheal tube too low (Fig. 5-13)

Endotracheal tube too low (Fig. 5-13)

Atelectasis of the entire lung (see Figs. 5-3 and 5-4)

Atelectasis of the entire lung (see Figs. 5-3 and 5-4)

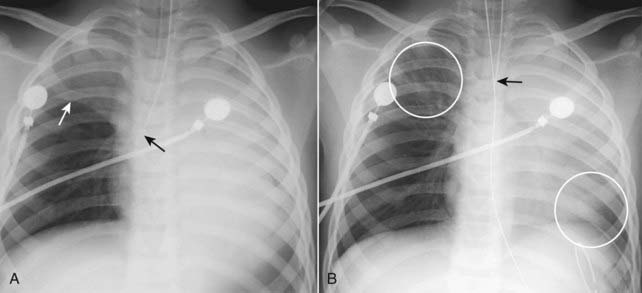

Figure 5-13 Right upper lobe and left lung atelectasis from an endotracheal tube.

A, The tip of the endotracheal tube extends beyond the carina into the bronchus intermedius (solid black arrow), which aerates only the right middle and lower lobes. The right upper lobe and entire left lung are opaque from atelectasis. The minor fissure is elevated (solid white arrow). B, One hour later, the tip of the endotracheal tube has been retracted above the carina (solid black arrow) and the right upper lobe and a portion of the left lower lobe are again aerated (white circles).

How Atelectasis Resolves

Depending in part on the rapidity with which the segment, lobe, or lung became atelectatic, atelectasis has the capacity to resolve within hours or last for many days once the obstruction has been removed.

Depending in part on the rapidity with which the segment, lobe, or lung became atelectatic, atelectasis has the capacity to resolve within hours or last for many days once the obstruction has been removed. Slowly-resolving lobar or whole-lung atelectasis may manifest patchy areas of airspace disease surrounded by progressively increasing zones of aerated lung until the atelectasis has completely cleared.

Slowly-resolving lobar or whole-lung atelectasis may manifest patchy areas of airspace disease surrounded by progressively increasing zones of aerated lung until the atelectasis has completely cleared.TABLE 5-2 MOST COMMON CAUSES OF OBSTRUCTIVE ATELECTASIS

| Cause | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Tumors | Includes bronchogenic carcinoma (especially squamous cell), endobronchial metastases, and carcinoid tumors |

| Mucous plug | Especially in bedridden individuals; postoperative patients; those with asthma, cystic fibrosis |

| Foreign body aspiration | Especially peanuts; toys; following a traumatic intubation |

| Inflammation | As in scarring caused by tuberculosis |

Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Recognizing Atelectasis on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Recognizing Atelectasis

Volume loss is common to all forms of atelectasis, but the radiographic appearance of atelectasis will differ depending on the type of atelectasis.

The three most commonly observed types of atelectasis are subsegmental atelectasis (also known as discoid or platelike atelectasis), compressive or passive atelectasis, and obstructive atelectasis.

Subsegmental atelectasis usually occurs in patients who are not taking a deep breath (splinting) and produces horizontal linear densities, usually at the lung bases.

Compressive atelectasis occurs passively when the lung is collapsed by a poor inspiration (at the bases), or from a large, adjacent pleural effusion or pneumothorax. When the underlying abnormality is removed, the lung usually expands.

Round atelectasis is a type of passive atelectasis in which the lung does not re-expand when a pleural effusion recedes, usually due to pre-existing pleural disease. Round atelectasis may produce a masslike lesion that can mimic a tumor on chest radiographs.

Obstructive atelectasis occurs distal to an occluding lesion of the bronchial tree because of reabsorption of the air in the distal airspaces via the pulmonary capillary bed.

Obstructive atelectasis produces consistently recognizable patterns of collapse based on the assumptions that the visceral and parietal pleura invariably remain in contact with each other and every lobe of the lung is anchored at or near the hilum.

Signs of obstructive atelectasis include displacement of the fissures, increased density of the affected lung, shift of the mobile structures of the thorax toward the atelectasis, and compensatory overinflation of the unaffected ipsilateral or contralateral lung.

Atelectasis tends to resolve quickly if it occurs acutely; the more chronic the process, the longer it usually takes to resolve.