Chapter 8 Recognizing Pneumothorax, Pneumomediastinum, Pneumopericardium, and Subcutaneous Emphysema

Recognizing A Pneumothorax

A pneumothorax occurs when air enters the pleural space.

A pneumothorax occurs when air enters the pleural space.

![]() You must be able to identify the visceral pleural line (Fig. 8-1) to make the definitive diagnosis of a pneumothorax!

You must be able to identify the visceral pleural line (Fig. 8-1) to make the definitive diagnosis of a pneumothorax!

Even as the lung collapses, it tends to maintain its usual lunglike shape so that the curvature of the visceral pleural line parallels the curvature of the chest wall; that is, the visceral pleural line is convex outward toward the chest wall (Fig. 8-2).

Even as the lung collapses, it tends to maintain its usual lunglike shape so that the curvature of the visceral pleural line parallels the curvature of the chest wall; that is, the visceral pleural line is convex outward toward the chest wall (Fig. 8-2).

There is usually, but not always, an absence of lung markings peripheral to the visceral pleural line.

There is usually, but not always, an absence of lung markings peripheral to the visceral pleural line.

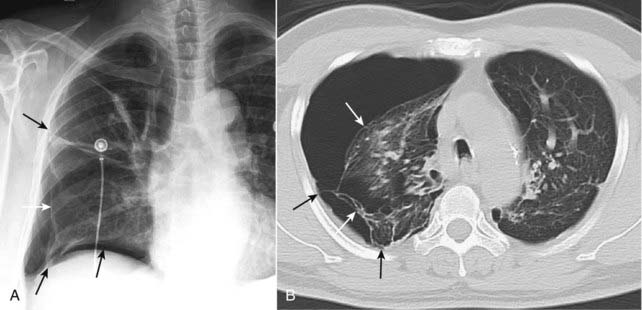

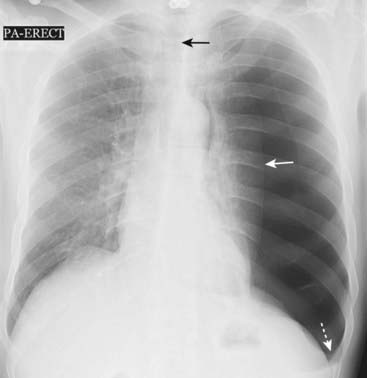

Figure 8-1 Visceral pleural line in a pneumothorax.

You must see the visceral pleural line to make the definitive diagnosis of a pneumothorax (solid white arrows). The visceral and parietal pleurae are normally not visible, both normally lying adjacent to the lateral chest wall. When air enters the pleural space, the visceral pleura retracts toward the hilum along with the collapsing lung and becomes visible as a very thin, white line with air outlining it on either side. Notice how the contour of the pneumothorax parallels the curvature of the adjacent chest wall.

Figure 8-2 Pneumothorax seen on CT.

As the lung collapses, it tends to maintain its usual shape so that the curve of the visceral pleural line (solid white arrows) parallels the curve of the chest wall (dotted white arrows). This is important in differentiating a pneumothorax from artifacts or other diseases that can mimic a pneumothorax. As it collapses, the lung on the side of the pneumothorax also tends to remain lucent until the lung loses almost all of its normal volume, at which point it appears opaque. This patient also has subcutaneous emphysema—air in the soft tissues—of the left lateral chest wall (white stars). The patient had suffered a stab wound.

![]() Pitfall: Pleural adhesions may keep part, but not all, of the visceral pleura adherent to the parietal pleura, even in the presence of a pneumothorax (Fig. 8-3).

Pitfall: Pleural adhesions may keep part, but not all, of the visceral pleura adherent to the parietal pleura, even in the presence of a pneumothorax (Fig. 8-3).

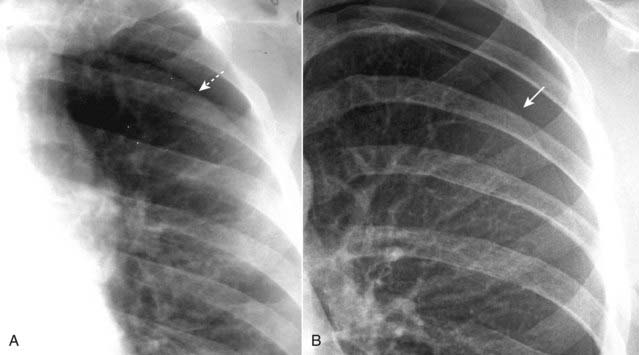

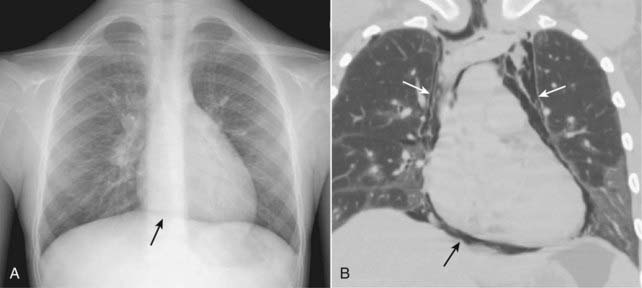

Figure 8-3 Pneumothorax with pleural adhesions.

Lung markings may be visible on a conventional radiograph of the chest, distal to the visceral pleural line if pleural adhesions are present. In (A), a pneumothorax (solid white arrows) is prevented from collapsing the lung by pleural adhesions (solid black arrows). On a CT scan (B), the pleural adhesions (solid black arrows) are seen tethering the lung (solid white arrows) to the parietal pleura. Adhesions most frequently result from prior infection or blood in the pleural space.

The presence of an air-fluid interface in the pleural space is, by definition, an indication that a pneumothorax is present (see Fig. 6-14).

The presence of an air-fluid interface in the pleural space is, by definition, an indication that a pneumothorax is present (see Fig. 6-14).

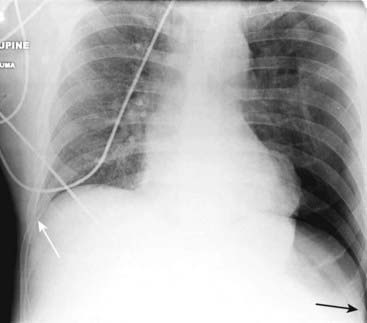

In the supine position, air in a relatively large pneumothorax may collect anteriorly and inferiorly in the thorax and manifest itself by displacing the costophrenic sulcus inferiorly while, at the same time, producing increased lucency of that costophrenic sulcus.

In the supine position, air in a relatively large pneumothorax may collect anteriorly and inferiorly in the thorax and manifest itself by displacing the costophrenic sulcus inferiorly while, at the same time, producing increased lucency of that costophrenic sulcus.

In the supine position, air in a relatively large pneumothorax may collect anteriorly and inferiorly in the thorax and manifest itself by displacing the costophrenic sulcus inferiorly while, at the same time, producing increased lucency of that sulcus (solid black arrow). This is called the deep sulcus sign and is an indication of a pneumothorax on a supine radiograph. Notice how much lower the left costophrenic sulcus appears than the right sulcus (solid white arrow).

Recognizing the Pitfalls in Overdiagnosing A Pneumothorax

Several pitfalls can lead to the mistaken diagnosis of a pneumothorax.

Several pitfalls can lead to the mistaken diagnosis of a pneumothorax.

![]() Pitfall 1: Absence of lung markings mistaken for a pneumothorax.

Pitfall 1: Absence of lung markings mistaken for a pneumothorax.

Figure 8-5 Bullous disease, right upper lobe.

A thin, white line is visible on this close-up of the right upper lobe (solid white arrows) and no lung markings are seen peripheral to it. Unlike the visceral pleural line of a pneumothorax, this white line is convex away from the chest wall and does not parallel the curve of the chest wall. This is the classical appearance of a bulla in a patient with emphysema. It is important to differentiate between a pneumothorax and a bulla because inadvertently placing a chest tube into a bulla will almost always produce a pneumothorax which may be difficult to re-expand. The walls of several bullae are visible in this patient (dotted white arrows). On rare occasions, the bullae can grow so large as to render the hemithorax seemingly devoid of visible lung tissue (vanishing lung syndrome).

Figure 8-6 Bullous disease on right; pneumothorax on left.

This axial section from a chest CT demonstrates the different appearances of bullous disease, seen on the right with its border convex away from the chest wall (dotted white arrow), and a pneumothorax seen here on the left with its border convex toward and paralleling the chest wall (solid white arrow). This patient also has subcutaneous emphysema on the left (solid black arrow).

Figure 8-7 Skin fold mimicking a pneumothorax.

When patients lie directly on the radiographic cassette as they might for a portable, supine radiograph, a fold of the patient’s skin may become trapped between the patient’s back and the surface of the cassette. This can produce an edge (dotted white arrow) in the expected position of a pneumothorax, and that edge may parallel the chest wall just as you would expect a pneumothorax to do (A). Unlike the thin, white line of the visceral pleura in a different patient with a pneumothorax (solid white arrow—in B), skin folds produce relatively thick, white bands of density. A skin fold is an edge; the visceral pleura produces a line.

![]() Pitfall 3: Mistaking the medial border of the scapula for a pneumothorax.

Pitfall 3: Mistaking the medial border of the scapula for a pneumothorax.

Figure 8-8 Scapular edge mimicking a pneumothorax.

The patient is usually positioned for an upright frontal chest radiograph in such a way that the medial edges of the scapulae are retracted lateral to the outer edges of the rib cage, thus reducing the risk that the scapulae will produce superimposed densities on the chest. On supine radiographs, the medial border of the scapula (solid white arrows) will frequently superimpose on the upper lung field and may mimic the visceral pleural line of a pneumothorax. Before you diagnose a pneumothorax, make sure you can identify the medial border of the scapula as being separate from the suspected pneumothorax.

Types of Pneumothoraces

Pneumothoraces can be categorized as primary, i.e., occurring in what appears to have been normal lung (spontaneous pneumothorax being an example), or secondary, i.e., those that occur in diseased lung (as in emphysema).

Pneumothoraces can be categorized as primary, i.e., occurring in what appears to have been normal lung (spontaneous pneumothorax being an example), or secondary, i.e., those that occur in diseased lung (as in emphysema). They have also been classified based on the presence or absence of a “shift” of the mobile mediastinal structures, like the heart and trachea.

They have also been classified based on the presence or absence of a “shift” of the mobile mediastinal structures, like the heart and trachea.

Tension pneumothoraces are associated with a shift of the mediastinal structures away from the side of the pneumothorax; simple pneumothoraces are not associated with any shift. The heart or mediastinal structures never shift toward the side of a pneumothorax.

Tension pneumothoraces are associated with a shift of the mediastinal structures away from the side of the pneumothorax; simple pneumothoraces are not associated with any shift. The heart or mediastinal structures never shift toward the side of a pneumothorax. The question “How large is the pneumothorax?” is common but the actual issue is “Does this patient require a chest tube to drain the pneumothorax?” Box 8-2 summarizes the answer.

The question “How large is the pneumothorax?” is common but the actual issue is “Does this patient require a chest tube to drain the pneumothorax?” Box 8-2 summarizes the answer.

Figure 8-9 Pneumothorax with no shift.

A large left-sided pneumothorax (solid white arrows) demonstrates no shift of the heart or trachea to the right. Subcutaneous emphysema is seen in the region of the left shoulder (solid black arrow). Can you detect why the patient had all of these findings? Yes, that’s a bullet superimposed on the heart (but on CT it was posterior to the heart in the left lower lobe).

Figure 8-10 Large left-sided tension pneumothorax.

Progressive loss of air into the pleural space through a one-way check-valve mechanism may cause a shift of the heart and mediastinal structures away from the side of the pneumothorax and lead to cardiopulmonary compromise by impairing venous return to the heart. In this patient with a spontaneous pneumothorax, the left lung is almost totally collapsed (solid white arrow) and the trachea (solid black arrow) and heart have shifted to the right. The left hemidiaphragm is depressed because of the elevated left intrathoracic pressure (dotted white arrow).

Box 8-2 How Large is the Pneumothorax?

Other Ways to Diagnose A Pneumothorax

CT of the chest

CT of the chest

Expiratory chest x-rays

Expiratory chest x-rays

Decubitus chest x-rays

Decubitus chest x-rays

Delayed films are sometimes obtained about 6 hours after a penetrating injury to the chest in patients in whom no pneumothorax is visible on the initial examination because of the occasional appearance of a delayed traumatic pneumothorax.

Delayed films are sometimes obtained about 6 hours after a penetrating injury to the chest in patients in whom no pneumothorax is visible on the initial examination because of the occasional appearance of a delayed traumatic pneumothorax.

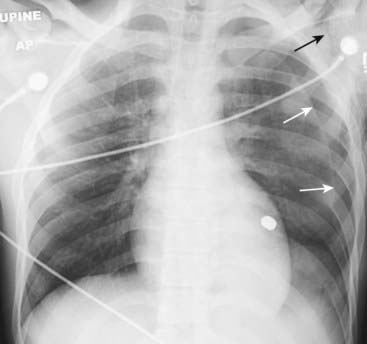

Figure 8-11 Bilateral pneumothoraces.

Conventional radiography is the initial modality used for detecting pneumothorax, but smaller pneumothoraces may be visible only on CT scans of the chest. This patient has bilateral pneumothoraces (solid white arrows). Air will rise to the highest point (the patient is supine in the CT scanner). Extensive subcutaneous emphysema also is present (solid black arrows); it developed because of an “air leak” from a chest tube that had been inserted earlier.

Pulmonary Interstitial Emphysema

When the pressure or volume in the alveolus becomes sufficiently elevated, the alveolus may rupture.

When the pressure or volume in the alveolus becomes sufficiently elevated, the alveolus may rupture. This extraalveolar air may take one of two paths:

This extraalveolar air may take one of two paths:

The air that tracks backward towards the hilum does so along the perivascular connective tissue of the lung forming small, cystic collections of extra-alveolar air which dissect retrograde through the bronchovascular sheaths to the hila.

The air that tracks backward towards the hilum does so along the perivascular connective tissue of the lung forming small, cystic collections of extra-alveolar air which dissect retrograde through the bronchovascular sheaths to the hila.

Presumably because of the looser connective tissue in the lungs of children and young adults, pulmonary interstitial emphysema is more likely to occur in those under the age of 40.

Presumably because of the looser connective tissue in the lungs of children and young adults, pulmonary interstitial emphysema is more likely to occur in those under the age of 40.

Pulmonary interstitial emphysema may not be recognizable on conventional radiographs because the air collections are small and a considerable amount of coexisting disease is usually present in the lung that obscures it. It may, however, be more visible on CT scans of the chest (Fig. 8-12).

Pulmonary interstitial emphysema may not be recognizable on conventional radiographs because the air collections are small and a considerable amount of coexisting disease is usually present in the lung that obscures it. It may, however, be more visible on CT scans of the chest (Fig. 8-12).

Figure 8-12 Pulmonary interstitial emphysema.

This coronal reformatted CT scan of the chest demonstrates air (solid white arrows) surrounding the pulmonary arteries (white branching structures) in the lung. This air arose from a ruptured alveolus in a patient with asthma and is tracking back to the hilum where it also produced pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema. The patient also has bilateral, basilar pneumothoraces (dotted white arrows).

![]() Pitfall: In infants with hyaline membrane disease (respiratory distress syndrome), pulmonary interstitial emphysema may lead to the appearance of pseudoclearing of the lungs (which can appear less dense overall from the formation of the innumerable small air pockets) but its presence actually portends more serious complications.

Pitfall: In infants with hyaline membrane disease (respiratory distress syndrome), pulmonary interstitial emphysema may lead to the appearance of pseudoclearing of the lungs (which can appear less dense overall from the formation of the innumerable small air pockets) but its presence actually portends more serious complications.

Recognizing Pneumomediastinum

When intra-alveolar pressure rises sufficiently to rupture the alveolus, air can track backward along the bronchovascular bundles in the lung to the mediastinum.

When intra-alveolar pressure rises sufficiently to rupture the alveolus, air can track backward along the bronchovascular bundles in the lung to the mediastinum. About 1 in 3 patients with pulmonary interstitial emphysema will develop pneumomediastinum (most will develop a pneumothorax).

About 1 in 3 patients with pulmonary interstitial emphysema will develop pneumomediastinum (most will develop a pneumothorax). Pneumomediastinum may also develop when an air-containing mediastinal viscus, such as the esophagus or tracheobronchial tree, is perforated.

Pneumomediastinum may also develop when an air-containing mediastinal viscus, such as the esophagus or tracheobronchial tree, is perforated.

Figure 8-13 Pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium and subcutaneous emphysema.

This patient with asthma developed spontaneous pneumomediastinum, most likely from rupture of an alveolus followed by formation of pulmonary interstitial emphysema. The air tracked back to the hila, then into the mediastinum where it produced streaky white, linear densities (solid white arrows) extending to the neck. Subcutaneous emphysema (dotted black arrows) is present in the neck. In adults, air does not usually enter the pericardium except by direct penetration, so it is somewhat unusual that this patient also developed pneumopericardium (solid black arrows). Notice how the air in the pericardial space does not extend above the reflections of the aorta and pulmonary artery, unlike pneumomediastinum which does extend above the great vessels.

Figure 8-14 Continuous diaphragm sign of pneumomediastinum.

With pneumomediastinum, air can outline the central portion of the diaphragm beneath the heart, producing an unbroken diaphragmatic contour that extends from one lateral chest wall to the other (solid black arrow on conventional radiograph A). This is called the continuous diaphragm sign. Normally, the diaphragm is not visible in the center of the chest because no air is in the mediastinum and the soft tissue density of the heart rests upon and silhouettes the soft tissue density of the diaphragm in its central portion. In (B), a coronal reformatted CT scan of the chest in another patient shows pneumomediastinum outlining the central portion of the diaphragm (solid black arrow) and the remainder of the pneumomediastinum extending superior to the great vessels (solid white arrows).

Recognizing Pneumopericardium

Pneumopericardium is usually due to direct penetrating injuries to the pericardium, either caused iatrogenically (during cardiac surgery) or accidentally (from penetrating trauma).

Pneumopericardium is usually due to direct penetrating injuries to the pericardium, either caused iatrogenically (during cardiac surgery) or accidentally (from penetrating trauma).

It is rare for air in the pleural space to enter the pericardium, except in those who have a pericardial defect, such as a surgical “window” incised in the pericardium which allows free exchange between the pleural and pericardial spaces.

It is rare for air in the pleural space to enter the pericardium, except in those who have a pericardial defect, such as a surgical “window” incised in the pericardium which allows free exchange between the pleural and pericardial spaces.

![]() Pneumopericardium produces a continuous band of lucency that encircles the heart, bound by the parietal pericardial layer which extends no higher than the root of the great vessels (corresponding to the level of the main pulmonary artery) (Fig. 8-15).

Pneumopericardium produces a continuous band of lucency that encircles the heart, bound by the parietal pericardial layer which extends no higher than the root of the great vessels (corresponding to the level of the main pulmonary artery) (Fig. 8-15).

Figure 8-15 Pneumopericardium.

This patient underwent a procedure to produce a pericardial window for recurrent pericardial effusions. Postoperatively, there is a pneumopericardium shown by the visible parietal pericardium (solid white arrows) outlining air around the heart in the pericardial space. Notice how the air does not extend above the reflection of the aorta and main pulmonary artery. Pneumopericardium in adults usually occurs from direct violation of the pericardium by trauma.

Recognizing Subcutaneous Emphysema

Air can extend into the soft tissues of the neck, chest and abdominal walls from the mediastinum, or it can dissect in the subcutaneous tissues from a thoracotomy drainage tube or a penetrating injury to the chest wall.

Air can extend into the soft tissues of the neck, chest and abdominal walls from the mediastinum, or it can dissect in the subcutaneous tissues from a thoracotomy drainage tube or a penetrating injury to the chest wall. Air dissecting along muscle bundles produces a characteristic comblike, striated appearance that superimposes on the underlying lung, often making it difficult to evaluate the lungs by conventional radiography (Fig. 8-16).

Air dissecting along muscle bundles produces a characteristic comblike, striated appearance that superimposes on the underlying lung, often making it difficult to evaluate the lungs by conventional radiography (Fig. 8-16). Although dramatic radiographically, subcutaneous emphysema usually produces no serious clinical effects by itself.

Although dramatic radiographically, subcutaneous emphysema usually produces no serious clinical effects by itself. Depending on the volume of subcutaneous air present, it may require several days to a week or longer for the air to reabsorb.

Depending on the volume of subcutaneous air present, it may require several days to a week or longer for the air to reabsorb.

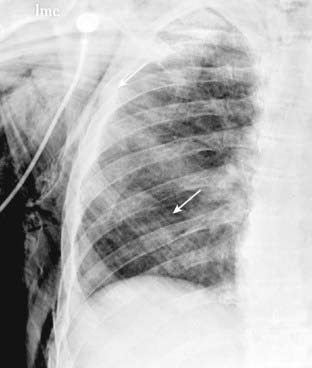

Figure 8-16 Subcutaneous emphysema.

Air can extend into the subcutaneous tissues of the neck, chest, and abdominal walls from the mediastinum, or it can dissect in the soft tissues from a thoracotomy drainage tube or a penetrating injury to the chest wall. Air dissecting along muscle bundles produces a characteristic comblike, striated appearance (solid white arrows). Although dramatic radiographically, subcutaneous emphysema usually produces no serious clinical effects by itself.

Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Recognizing Pneumothorax, Pneumomediastinum, Pneumopericardium, and Subcutaneous Emphysema on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Recognizing Pneumothorax, Pneumomediastinum, Pneumopericardium, and Subcutaneous Emphysema

There is normally no air in the pleural space; air in the pleural space is called a pneumothorax.

You must identify the visceral pleural white line to diagnose a pneumothorax.

Beware of the pitfalls that resemble pneumothoraces: bullae, skin folds, and the medial border of the scapula.

Simple pneumothoraces are those with no shift of the heart or mobile mediastinal structures; most pneumothoraces are simple.

Tension pneumothoraces (usually associated with cardiorespiratory compromise) produce a shift of the heart and mediastinal structures away from the side of the pneumothorax by virtue of a check-valve mechanism that allows air to enter the pleural space but not leave.

Most pneumothoraces are traumatic in etiology, either accidental or idiopathic.

Conventional chest radiographs are poor at estimating the size of a pneumothorax; CT is better; the most important assessment to be made is the clinical status of the patient.

Besides the conventional upright chest radiograph, other ways to diagnose a pneumothorax include: expiratory exposures, decubitus views, and delayed images. CT remains the most sensitive test for detecting small pneumothoraces.

Spontaneous pneumothoraces most often occur as a result of rupture of a small apical, sub-pleural bleb; they most often occur in younger men.

Pulmonary interstitial emphysema results from an increase in the intralveolar pressure that leads to rupture of an alveolus and dissection of air back towards the hila along the bronchovascular bundles; it is frequently difficult to visualize.

Pneumomediastinum can occur when air tracks back to the mediastinum from a ruptured alveolus or from perforation of an air-containing viscus such as the esophagus or trachea; it can produce the continuous diaphragm sign on a frontal chest radiograph.

Pneumopericardium usually is due to direct penetration of the pericardium rather than dissection of air from a pneumomediastinum; it can be difficult to differentiate from a pneumomediastinum. A key is that pneumopericardium does not extend above the roots of the great vessels, whereas pneumomediastinum does.

Air dissecting into the neck and chest wall can produce subcutaneous emphysema, which, because of its superimposition on the lungs, can make evaluation of the underlying lung more difficult. By itself, it is usually of no clinical significance and usually clears in a few days, depending on its volume.