Chapter 6 Recognizing a Pleural Effusion

Normal Anatomy and Physiology of the Pleural Space

Normal anatomy

Normal anatomy

Causes of Pleural Effusions

Fluid accumulates in the pleural space when the rate at which the fluid forms exceeds the rate by which it is cleared.

Fluid accumulates in the pleural space when the rate at which the fluid forms exceeds the rate by which it is cleared.

Pleural effusions can also form when there is transport of peritoneal fluid from the abdominal cavity through the diaphragm or via lymphatics from a subdiaphragmatic process (Table 6-1).

Pleural effusions can also form when there is transport of peritoneal fluid from the abdominal cavity through the diaphragm or via lymphatics from a subdiaphragmatic process (Table 6-1).TABLE 6-1 SOME CAUSES OF PLEURAL EFFUSIONS

| Cause | Examples |

|---|---|

| Excess formation of fluid | Congestive heart failure |

| Hyponatremia | |

| Parapneumonic effusions | |

| Hypersensitivity reactions | |

| Decreased resorption of fluid | Lymphangitic blockade from tumor |

| Elevated central venous pressure | |

| Decreased intrapleural pressure | |

| Transport from peritoneal cavity | Ascites |

Types of Pleural Effusions

Pleural effusions are divided into exudates or transudates, depending on their protein content and their lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) concentrations.

Pleural effusions are divided into exudates or transudates, depending on their protein content and their lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) concentrations.Side Specificity of Pleural Effusions

Diseases that usually produce right-sided effusions:

Diseases that usually produce right-sided effusions:

Box 6-1 Dressler Syndrome

Figure 6-1 Dressler syndrome (postpericardiotomy/postmyocardial infarction syndrome).

A left pleural effusion (A) is present (solid black arrows). This syndrome typically occurs 2 to 3 weeks after a transmural myocardial infarct. It also can occur following pericardiotomy such as occurs in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery, as in this case. The combination of chest pain and fever, left pleural effusion, patchy left lower lobe airspace disease, and pericardial effusion several weeks following a myocardial infarction or open-heart surgery should suggest the syndrome. It usually responds to high-dose aspirin or steroids. This patient has a dual lead pacemaker in place and, on the lateral projection (B), the leads are seen in the region of the right atrium (dotted black arrow) and right ventricle (arrowhead).

Recognizing the Different Appearances of Pleural Effusions

Forces that influence the appearance of pleural fluid on a chest radiograph depend on the position of the patient, the force of gravity, the amount of fluid and the degree of elastic recoil of the lung.

Forces that influence the appearance of pleural fluid on a chest radiograph depend on the position of the patient, the force of gravity, the amount of fluid and the degree of elastic recoil of the lung. The descriptions that follow, unless otherwise indicated, assume the patient is in the upright position.

The descriptions that follow, unless otherwise indicated, assume the patient is in the upright position.Subpulmonic Effusions

It is believed that almost all pleural effusions first collect in a subpulmonic location beneath the lung between the parietal pleura lining the superior surface of the diaphragm and the visceral pleura under the lower lobe.

It is believed that almost all pleural effusions first collect in a subpulmonic location beneath the lung between the parietal pleura lining the superior surface of the diaphragm and the visceral pleura under the lower lobe. If the effusion remains entirely subpulmonic in location, it can be difficult to detect on conventional radiographs except for contour alterations in what appears to be the hemidiaphragm but is actually the fluid-lung interface beneath the lung.

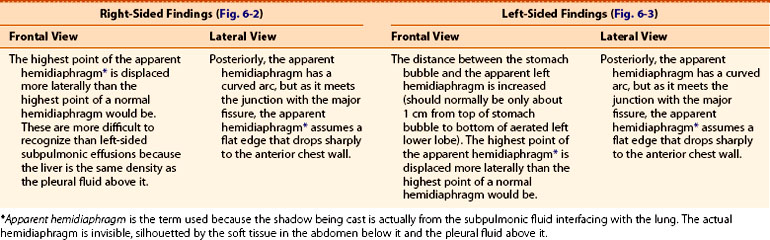

If the effusion remains entirely subpulmonic in location, it can be difficult to detect on conventional radiographs except for contour alterations in what appears to be the hemidiaphragm but is actually the fluid-lung interface beneath the lung. The different appearances of subpulmonic effusions are summarized in Table 6-2 (Figs. 6-2 and 6-3).

The different appearances of subpulmonic effusions are summarized in Table 6-2 (Figs. 6-2 and 6-3).

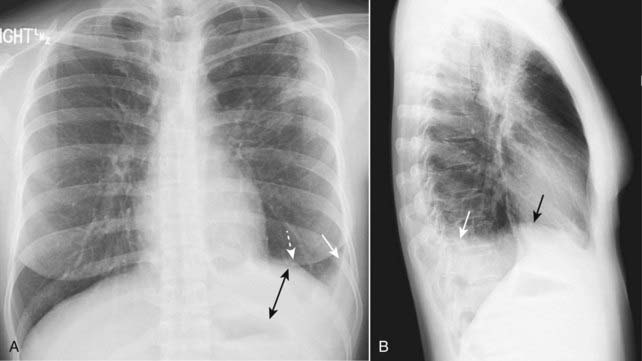

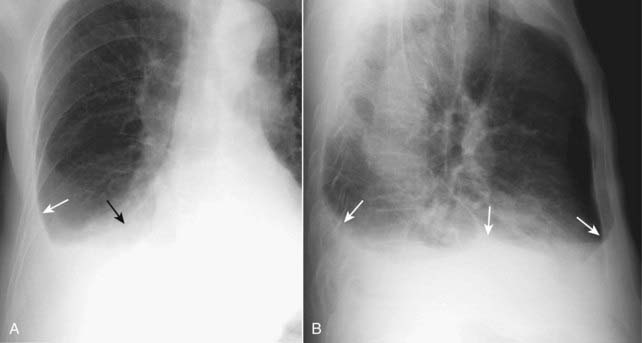

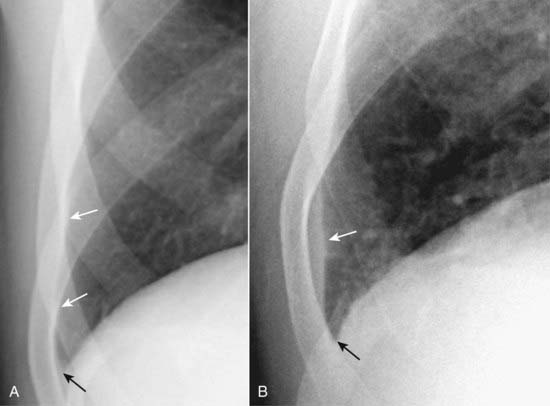

Figure 6-2 Right-sided subpulmonic effusion.

In the frontal projection (A), the apparent right hemidiaphragm appears to be elevated (solid black arrow). This edge does not represent the actual right hemidiaphragm, which has been rendered invisible by the pleural fluid that has accumulated above it, but the interface between the effusion and the base of the lung (thus the term “apparent hemidiaphragm”). There is blunting of the right costophrenic sulcus (solid white arrow). On the lateral projection (B), there is blunting of the posterior costophrenic sulcus (solid white arrow). The apparent hemidiaphragm is rounded posteriorly but then changes its contour as the effusion interfaces with the major fissure on the left side (solid black arrow).

Figure 6-3 Left-sided subpulmonic effusion.

In the frontal projection (A), more than 1 cm distance is seen between the air in the stomach and the apparent left hemidiaphragm (double black arrow). The edge between the aerated lung and the dotted white arrow does not represent the actual left hemidiaphragm, which has been rendered invisible by the pleural fluid that has accumulated above it, but the interface between the effusion and the base of the lung. There is blunting of the left costophrenic sulcus (solid white arrow) on both projections. On the lateral projection (B), the apparent hemidiaphragm is rounded posteriorly but then changes its contour as the effusion interfaces with the major fissure (solid black arrow).

Blunting of the Costophrenic Angles

As the subpulmonic effusion grows in size, it first fills and blunts the posterior costophrenic sulcus, visible on the lateral view of the chest (Fig. 6-4).

As the subpulmonic effusion grows in size, it first fills and blunts the posterior costophrenic sulcus, visible on the lateral view of the chest (Fig. 6-4).

When the effusion reaches about 300 mL in size, it blunts the lateral costophrenic angle, visible on the frontal chest radiograph (Fig. 6-5).

When the effusion reaches about 300 mL in size, it blunts the lateral costophrenic angle, visible on the frontal chest radiograph (Fig. 6-5).

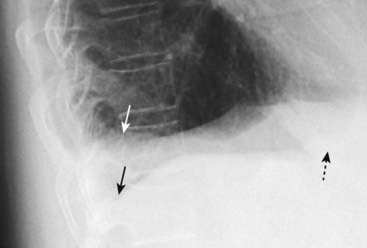

Figure 6-4 Blunting of the right posterior costophrenic sulcus on the lateral projection.

When approximately 75 mL of fluid has accumulated in the pleural space, the fluid will typically blunt the posterior costophrenic sulcus (angle) first (solid white arrow). This can be visualized only on the lateral projection. A normal, sharp posterior costophrenic angle is visible on the opposite side (solid black arrow). Notice how the normal left hemidiaphragm is silhouetted by the heart anteriorly (dotted black arrow) indicating that is the left hemidiaphragm. The pleural effusion is on the right side.

Figure 6-5 Normal and blunted right lateral costophrenic angle.

The hemidiaphragm usually makes a sharp and acute angle as it meets the lateral chest wall on the frontal projection (A) to produce the lateral costophrenic sulcus (solid black arrow). Notice how normally aerated lung extends to the inner margin of each of the ribs (solid white arrows). When an effusion reaches about 300 mL in volume (B), the lateral costophrenic sulcus loses its acute angulation and becomes blunted (solid black arrow).

![]() Pitfall: Pleural thickening caused by fibrosis can also produce blunting of the costophrenic angle.

Pitfall: Pleural thickening caused by fibrosis can also produce blunting of the costophrenic angle.

Figure 6-6 Scarring producing blunting of the left costophrenic angle.

Scarring from such things as previous infection, surgery, or blood in the pleural space sometimes produces a characteristic “ski-slope appearance” of blunting (solid black arrows), unlike the meniscoid appearance of a pleural effusion. This fibrosis would not change in appearance or location with a change in the patient’s position, as free-flowing pleural fluid would.

The Meniscus Sign

Because of the natural elastic recoil of the lungs, pleural fluid appears to rise higher along the lateral margin of the thorax than it does medially in the frontal projection. This produces a characteristic meniscus shape to the effusion.

Because of the natural elastic recoil of the lungs, pleural fluid appears to rise higher along the lateral margin of the thorax than it does medially in the frontal projection. This produces a characteristic meniscus shape to the effusion. In the lateral projection, the fluid assumes a U-shape ascending equally high both anteriorly and posteriorly (Fig. 6-7).

In the lateral projection, the fluid assumes a U-shape ascending equally high both anteriorly and posteriorly (Fig. 6-7).

Effect of patient positioning on the appearance of pleural fluid:

Effect of patient positioning on the appearance of pleural fluid:

Figure 6-7 Right pleural effusion, meniscoid appearance.

On the frontal projection in the upright position (A), an effusion typically ascends more laterally (solid white arrow) than it does medially (solid black arrow) because of factors affecting the natural elastic recoil of the lung. On the lateral projection (B) the fluid ascends about the same amount anteriorly and posteriorly, forming a U-shaped, meniscoid density (solid white arrows).

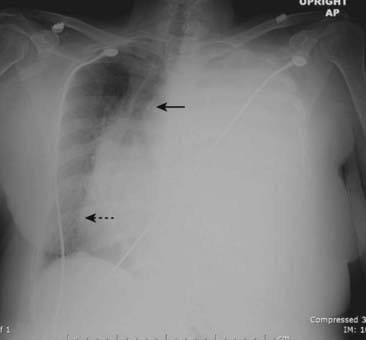

Figure 6-8 Effect of patient positioning on the appearance of a pleural effusion.

In the recumbent position (A), the right-sided effusion layers along the posterior pleural surface and produces a “haze” over the entire hemithorax that is densest at the base and less dense toward the apex of the lung (solid black arrow). In the same patient x-rayed a few minutes later in a more upright position (B), pleural fluid falls to the base of the thoracic cavity due to the force of gravity (solid white arrow). This simple change in position can produce the mistaken impression that an effusion has improved (or worsened if the supine study follows the upright examination) when there has actually been no change in the amount of pleural fluid. Ideally, the patient should be x-rayed in the same position each time for a meaningful comparison.

![]() Pitfall: Depending on the patient’s degree of recumbence, the upper lung fields may appear clearer if the patient is upright and the fluid settles to the base of the thorax or denser (whiter) as the patient becomes more recumbent and the effusion begins to layer posteriorly. This change in appearance can occur with the same volume of pleural fluid redistributed because of patient positioning.

Pitfall: Depending on the patient’s degree of recumbence, the upper lung fields may appear clearer if the patient is upright and the fluid settles to the base of the thorax or denser (whiter) as the patient becomes more recumbent and the effusion begins to layer posteriorly. This change in appearance can occur with the same volume of pleural fluid redistributed because of patient positioning.

The lateral decubitus view of the chest

The lateral decubitus view of the chest

![]() With a right lateral decubitus view of the chest, the patient’s right side will be dependent and a right pleural effusion will layer along the dependent surface. With a left lateral decubitus view of the chest, the patient’s left side will be dependent and a left pleural effusion will layer along the dependent surface (Fig. 6-9).

With a right lateral decubitus view of the chest, the patient’s right side will be dependent and a right pleural effusion will layer along the dependent surface. With a left lateral decubitus view of the chest, the patient’s left side will be dependent and a left pleural effusion will layer along the dependent surface (Fig. 6-9).

Figure 6-9 Decubitus views of the chest.

A, A right lateral decubitus view of the chest. The film is exposed with the patient lying on the right side on the examining table while a horizontal x-ray beam is directed posteroanteriorly (PA). Because the patient’s right side is dependent, any free-flowing pleural fluid will layer along the right side (solid black arrows), forming a bandlike density. Notice how the fluid flows into the minor fissure (dotted black arrow). B, A left lateral decubitus view of the chest. When the same patient lies on the table with the left side down, free fluid on the left side layers along the left lateral chest wall (solid black arrows). This patient has pleural effusions from lymphoma.

![]() Pitfall: Don’t order a lateral decubitus view of the chest if the entire hemithorax is opacified since there can be no change in the position of the fluid and the underlying lung will be no more visible in the decubitus position than it was with the patient upright. CT scan of the chest is a better means of evaluating the underlying lung if the hemithorax is opacified.

Pitfall: Don’t order a lateral decubitus view of the chest if the entire hemithorax is opacified since there can be no change in the position of the fluid and the underlying lung will be no more visible in the decubitus position than it was with the patient upright. CT scan of the chest is a better means of evaluating the underlying lung if the hemithorax is opacified.

Opacified Hemithorax

When the hemithorax of an adult contains about 2 L of fluid, the entire hemithorax will be opacified (Fig. 6-10).

When the hemithorax of an adult contains about 2 L of fluid, the entire hemithorax will be opacified (Fig. 6-10). As fluid fills the pleural space, the lung tends to undergo passive collapse (atelectasis) (see Chapter 5).

As fluid fills the pleural space, the lung tends to undergo passive collapse (atelectasis) (see Chapter 5). Large effusions are sufficiently opaque on conventional chest radiographs so as to mask whatever disease may be present in the lung enveloped by them. CT is the modality usually employed to visualize the underlying lung.

Large effusions are sufficiently opaque on conventional chest radiographs so as to mask whatever disease may be present in the lung enveloped by them. CT is the modality usually employed to visualize the underlying lung. Large effusions act like a mass and displace the heart and trachea away from the side of opacification (see Fig. 6-10).

Large effusions act like a mass and displace the heart and trachea away from the side of opacification (see Fig. 6-10). For more on the opacified hemithorax, go to Chapter 4, Recognizing the Causes of an Opacified Hemithorax.

For more on the opacified hemithorax, go to Chapter 4, Recognizing the Causes of an Opacified Hemithorax.

Figure 6-10 Large left pleural effusion.

The left hemithorax is completely opacified, and the mobile mediastinal structures such as the trachea (solid black arrow) and the heart (dotted black arrow) have shifted away from the side of opacification. This is characteristic of a large pleural effusion, which acts like a mass. In most adults, about 2 L of fluid is required to fill or almost fill the entire hemithorax such as this.

Loculated Effusions

Adhesions in the pleural space, caused most often by old empyema or hemothorax, may limit the normal mobility of a pleural effusion, so that it remains in the same location no matter what position the patient assumes.

Adhesions in the pleural space, caused most often by old empyema or hemothorax, may limit the normal mobility of a pleural effusion, so that it remains in the same location no matter what position the patient assumes. Imaging findings

Imaging findings

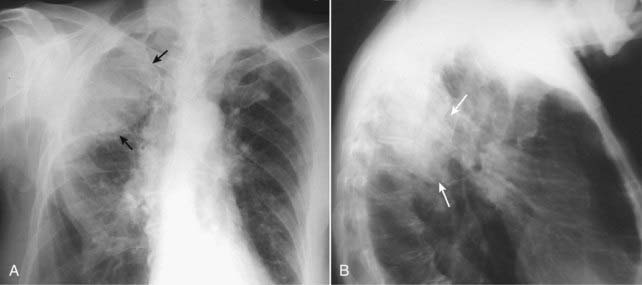

Figure 6-11 Loculated pleural effusion in frontal (A) and lateral (B) projections.

A pleural-based soft tissue density in the right upper lung field represents a loculated pleural effusion (solid black arrows in A and solid white arrows in B). Loculated effusions can be suspected when an effusion has an unusual shape or location in the thorax; for example, the effusion defies gravity by remaining at the apex of the lung even though the patient is upright.

Fissural Pseudotumors

Pseudotumors (also called vanishing tumors) are sharply marginated collections of pleural fluid contained between the layers of an interlobar pulmonary fissure or in a subpleural location just beneath the fissure.

Pseudotumors (also called vanishing tumors) are sharply marginated collections of pleural fluid contained between the layers of an interlobar pulmonary fissure or in a subpleural location just beneath the fissure. The imaging findings of a pseudotumor are characteristic so that they should not be mistaken for an actual tumor (from which they derive their name).

The imaging findings of a pseudotumor are characteristic so that they should not be mistaken for an actual tumor (from which they derive their name).

They disappear when the underlying condition (usually CHF) is treated, but they tend to recur in the same location each time the patient’s failure recurs (Fig. 6-12).

They disappear when the underlying condition (usually CHF) is treated, but they tend to recur in the same location each time the patient’s failure recurs (Fig. 6-12).

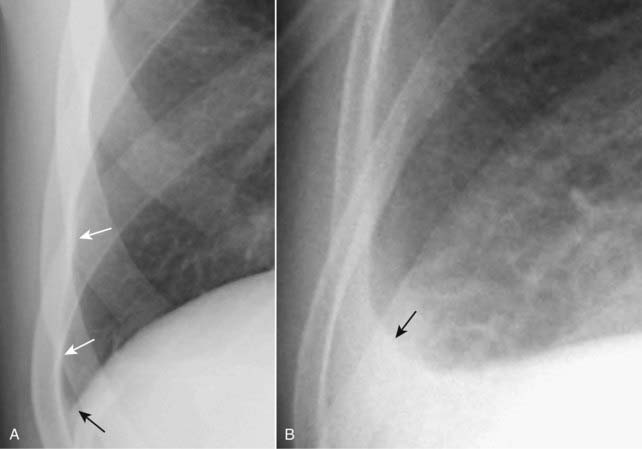

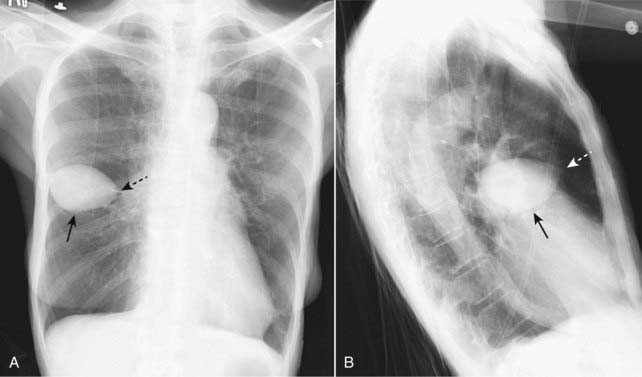

Figure 6-12 Pseudotumor in the minor fissure, frontal (A) and lateral (B) projection.

A sharply marginated collection of pleural fluid contained between the layers of the minor fissure produces a characteristic lenticular shape (solid black arrows in A and B) that frequently has pointed ends on each side where it insinuates into the fissure so that pseudotumors look like a lemon on frontal (A) or lateral (B) chest radiographs (dotted black arrow on A and dotted white arrow on B). Pseudotumors almost always occur in patients with congestive heart failure and, although the pseudotumors disappear when the underlying condition is treated, they frequently return each time the patient’s failure recurs.

Laminar Effusions

A laminar effusion is a form of pleural effusion in which the fluid assumes a thin, bandlike density along the lateral chest wall, especially near the costophrenic angle. Unlike a usual pleural effusion, the lateral costophrenic angle tends to maintain its acute angle with a laminar effusion.

A laminar effusion is a form of pleural effusion in which the fluid assumes a thin, bandlike density along the lateral chest wall, especially near the costophrenic angle. Unlike a usual pleural effusion, the lateral costophrenic angle tends to maintain its acute angle with a laminar effusion. Laminar effusions are almost always the result of elevated left atrial pressure, as in CHF or secondary to lymphangitic spread of malignancy. They are usually not free-flowing.

Laminar effusions are almost always the result of elevated left atrial pressure, as in CHF or secondary to lymphangitic spread of malignancy. They are usually not free-flowing. They can be recognized by the band of increased density that separates the air-filled lung from the inside margin of the ribs at the lung base on the frontal chest radiograph.

They can be recognized by the band of increased density that separates the air-filled lung from the inside margin of the ribs at the lung base on the frontal chest radiograph.

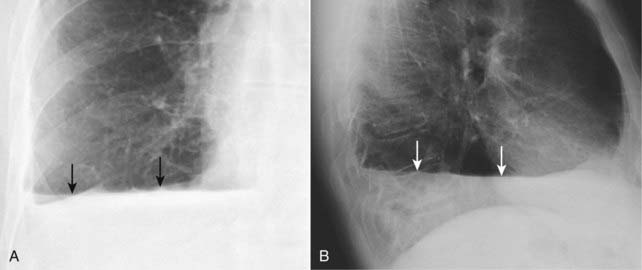

Figure 6-13 Normal patient versus laminar pleural effusion.

In A, which is a normal patient, notice how normally aerated lung extends to the inner margin of each of the ribs (solid white arrows). The costophrenic sulcus is sharp (closed black arrow). In B, a thin band of increased density extends superiorly from the lung base (solid white arrow) but does not appear to cause blunting of the costophrenic angle (solid black arrow). This is the appearance of a laminar pleural effusion that is most often associated with either congestive heart failure or lymphangitic spread of malignancy in the lung. This patient was in congestive heart failure.

Hydropneumothorax

The presence of both air in the pleural space (pneumothorax) and abnormal amounts of fluid in the pleural space (pleural effusion or hydrothorax) is called a hydropneumothorax.

The presence of both air in the pleural space (pneumothorax) and abnormal amounts of fluid in the pleural space (pleural effusion or hydrothorax) is called a hydropneumothorax. Some of the more common causes of a hydropneumothorax are trauma, surgery, or a recent tap to remove pleural fluid in which air enters the pleural apace.

Some of the more common causes of a hydropneumothorax are trauma, surgery, or a recent tap to remove pleural fluid in which air enters the pleural apace.

Unlike pleural effusion alone, whose mensicoid shape is governed by the elastic recoil of the lung, a hydropneumothorax produces an air-fluid level in the hemithorax marked by a straight edge and a sharp, air-over-fluid interface when the exposure is made with a horizontal x-ray beam (Fig. 6-14).

Unlike pleural effusion alone, whose mensicoid shape is governed by the elastic recoil of the lung, a hydropneumothorax produces an air-fluid level in the hemithorax marked by a straight edge and a sharp, air-over-fluid interface when the exposure is made with a horizontal x-ray beam (Fig. 6-14). CT is frequently necessary to distinguish between some presentations of hydropneumothorax and a lung abscess, both of which may have a similar appearance on conventional chest radiographs.

CT is frequently necessary to distinguish between some presentations of hydropneumothorax and a lung abscess, both of which may have a similar appearance on conventional chest radiographs.

Figure 6-14 Hydropneumothorax, frontal (A) and lateral (B) projections.

Unlike pleural effusions alone, whose meniscoid shape is governed by the elastic recoil of the lung, hydropneumothorax produces an air-fluid level in the hemithorax (solid black arrows in A and solid white arrows in B) marked by a straight edge and a sharp, air-over-fluid interface when the exposure is made with a horizontal x-ray beam. Surgery, trauma, a recent thoracentesis to remove pleural fluid, and bronchopleural fistulae are among the causes of a hydropneumothorax. This person was stabbed in the right side. This actually represents a hemopneumothorax, but conventional radiography is unable to distinguish between blood and any other fluid. A pleural tap might be necessary to better define the pleural fluid.

Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Recognizing a Pleural Effusion on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Recognizing a Pleural Effusion

Pleural effusions collect in the potential space between the visceral and parietal pleura and are either transudates or exudates depending on their protein content and LDH concentration.

There are normally a few milliliters of fluid in the pleural space; about 75 mL are required to blunt the posterior costophrenic sulcus (seen on the lateral view) and about 200-300 mL to blunt the lateral costophrenic sulcus (seen on the frontal view); approximately 2 L of fluid will cause opacification of the entire hemithorax in an adult.

Whether an effusion is unilateral or bilateral, mostly right-sided or mostly left-sided, can be an important clue as to its etiology.

Most pleural effusions begin life collecting in the pleural space between the hemidiaphragm and the base of the lung; these are called subpulmonic effusions.

As the amount of fluid increases, it forms a meniscus shape on the upright frontal chest radiograph due to the natural elastic recoil properties of the lung.

Very large pleural effusions act like a mass and characteristically produce a shift of the mobile mediastinal structures (e.g., the heart) away from the side of the effusion.

In the absence of pleural adhesions, effusions will flow freely and change location with a change in the patient’s position; with pleural adhesions (usually from old infection or hemothorax) the fluid may assume unusual appearances or occur in atypical locations; such effusions are said to be loculated.

A pseudotumor is a type of effusion that occurs in the fissures of the lung (mostly the minor fissure) and is most frequently secondary to congestive heart failure; it clears when the underlying failure is treated.

Laminar effusions are best recognized at the lung base just above the costophrenic angles on the frontal projection and most often occur as a result of either congestive heart failure or lymphangitic spread of malignancy.

A hydropneumothorax consists of both air and increased fluid in the pleural space and is recognizable on an upright view of the chest by a straight, air-fluid interface rather than the typical meniscus shape of pleural fluid alone.