Chapter 15 Recognizing Extraluminal Air in the Abdomen

Recognition of extraluminal air is an important finding that can have an immediate effect on the course of treatment.

Recognition of extraluminal air is an important finding that can have an immediate effect on the course of treatment. Air is normally not present in the peritoneal or extraperitoneal spaces, bowel wall, or biliary system.

Air is normally not present in the peritoneal or extraperitoneal spaces, bowel wall, or biliary system.

Signs Of Free Intraperitoneal Air

![]() There are three major signs of free intraperitoneal air arranged below in the order in which they are most commonly seen:

There are three major signs of free intraperitoneal air arranged below in the order in which they are most commonly seen:

Air Beneath the Diaphragm

Air will rise to the highest part of the abdomen. Therefore, in the upright position, free air will usually reveal itself under the diaphragm as a crescentic lucency that parallels the undersurface of the diaphragm (Fig. 15-1).

Air will rise to the highest part of the abdomen. Therefore, in the upright position, free air will usually reveal itself under the diaphragm as a crescentic lucency that parallels the undersurface of the diaphragm (Fig. 15-1).

While free air is best demonstrated on CT scans of the abdomen because of its greater sensitivity in detecting very small amounts of free air (Fig. 15-3), most surveys of the abdomen begin with conventional radiographs. Conventional radiographs serve as an important screening tool on which many previously unsuspected cases of free air are discovered.

While free air is best demonstrated on CT scans of the abdomen because of its greater sensitivity in detecting very small amounts of free air (Fig. 15-3), most surveys of the abdomen begin with conventional radiographs. Conventional radiographs serve as an important screening tool on which many previously unsuspected cases of free air are discovered.

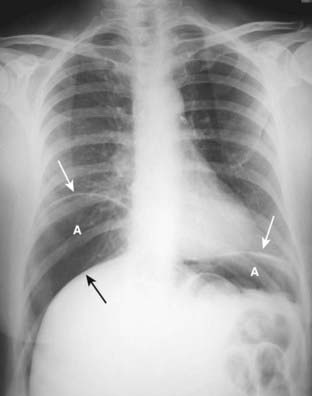

Figure 15-1 Free air beneath the diaphragm.

There are thin crescents of air beneath both the right (solid white arrow) and left (dotted white arrow) hemidiaphragms representing free intraperitoneal air. The patient had undergone abdominal surgery 3 days earlier. Free air can remain for up to 7 days after surgery in an adult, but serial studies should demonstrate a progressively decreasing amount of air.

Figure 15-2 Large amount of free air.

Upright view of the chest demonstrates a large amount of free air (A) beneath each hemidiaphragm (solid white arrows). The top of the liver (solid black arrow) is made visible by the air above it. The patient had a perforated gastric ulcer.

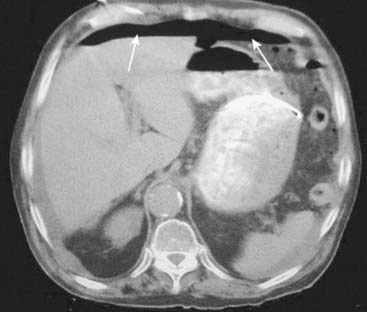

Figure 15-3 Free air seen on CT scan of the abdomen.

Axial CT scan of the upper abdomen performed with the patient supine shows free air anteriorly (solid white arrows). The air is not contained within any bowel. Free intraperitoneal air will normally rise to the highest point of the abdomen which, in the supine position, is beneath the anterior abdominal wall.

![]() On conventional radiographs, free air is best demonstrated with the x-ray beam directed parallel to the floor (i.e., a horizontal beam) (see Figs. 13-14 and 13-15). Small amounts of free air will not be visible on supine radiographs.

On conventional radiographs, free air is best demonstrated with the x-ray beam directed parallel to the floor (i.e., a horizontal beam) (see Figs. 13-14 and 13-15). Small amounts of free air will not be visible on supine radiographs.

Free air is easier to recognize under the right hemidiaphragm because only the soft tissue density of the liver is usually located there. Free air is more difficult to recognize under the left hemidiaphragm because air-containing structures, such as the fundus of the stomach and the splenic flexure, already reside in that location and may mask the presence of free air (Fig. 15-4).

Free air is easier to recognize under the right hemidiaphragm because only the soft tissue density of the liver is usually located there. Free air is more difficult to recognize under the left hemidiaphragm because air-containing structures, such as the fundus of the stomach and the splenic flexure, already reside in that location and may mask the presence of free air (Fig. 15-4). If the patient is unable to stand or sit upright, then a view of the abdomen with the patient lying on his or her left side taken with a horizontal x-ray beam may show free air rising above the right edge of the liver. This is the left lateral decubitus view of the abdomen (Fig. 15-5).

If the patient is unable to stand or sit upright, then a view of the abdomen with the patient lying on his or her left side taken with a horizontal x-ray beam may show free air rising above the right edge of the liver. This is the left lateral decubitus view of the abdomen (Fig. 15-5).

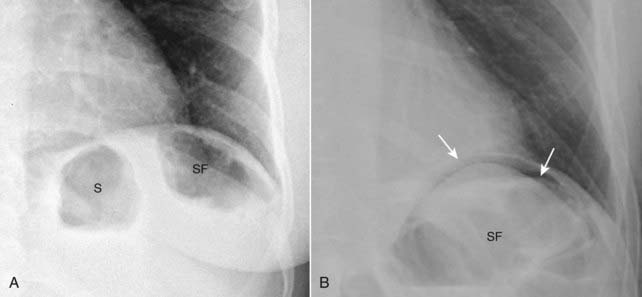

Figure 15-4 Normal left hemidiaphragm (A) and free air under hemidiaphragm (B).

Close-up views of the left upper quadrant demonstrate the difficulty in recognizing free air beneath the left hemidiaphragm because of the normal location of gas-containing structures such as the stomach (S) and splenic flexure (SF). There is no free air seen in (A) but the other patient (B) does have a crescent of free air (solid white arrows). It is easier to recognize free air beneath the right hemidiaphragm because there is usually no air present above the liver on the right side.

Figure 15-5 Left lateral decubitus view showing free air.

Close-up of the right upper quadrant in a patient lying on his or her left side in the left lateral decubitus position shows a crescent of air (dotted white arrows) above the outer edge of the liver (solid black arrow), beneath the right hemidiaphragm (solid white arrow). The head/foot orientation of the patient is indicated. If the patient is unable to stand or sit up for an upright view of the abdomen, a left lateral decubitus view with a horizontal beam can substitute.

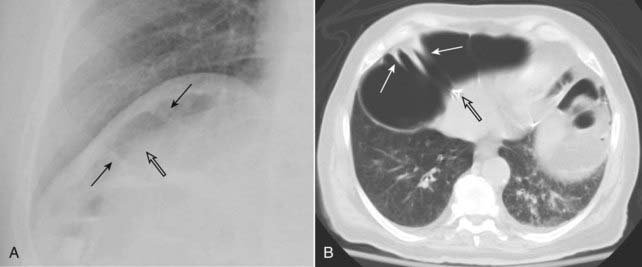

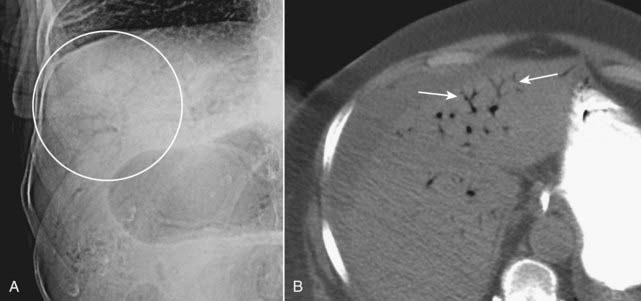

Figure 15-6 Chilaiditi syndrome.

Close-up of the right hemidiaphragm on a conventional chest radiograph (A) and an axial CT scan at the level of the diaphragm (B) both demonstrate air beneath the diaphragm that could be confused for free air (open black arrows in both photos). Careful evaluation of this air demonstrates several haustral folds (solid black arrows in [A] and solid white arrows in [B]) which indicate this is a loop of colon interposed between the liver and the diaphragm (Chilaiditi syndrome) rather than free air.

Visualization of Both Sides of the Bowel Wall

In the normal abdomen, we visualize only the air inside the lumen of the bowel, not the wall of the bowel itself. This is because the wall is soft tissue density and surrounded by tissue of the same density.

In the normal abdomen, we visualize only the air inside the lumen of the bowel, not the wall of the bowel itself. This is because the wall is soft tissue density and surrounded by tissue of the same density. Introduction of air into the peritoneal cavity enables us to visualize the wall of the bowel itself since the wall is now surrounded on both inside and outside by air.

Introduction of air into the peritoneal cavity enables us to visualize the wall of the bowel itself since the wall is now surrounded on both inside and outside by air.

When air fills the peritoneal cavity, both sides of the bowel wall will be outlined by air (solid white arrows) making the wall of the bowel visible as a discrete line. This is known as Rigler sign and indicates the presence of a pneumoperitoneum.

![]() Pitfall: When dilated loops of small bowel overlap each other, they may occasionally produce the mistaken impression that you are seeing both sides of the bowel wall (Fig. 15-8).

Pitfall: When dilated loops of small bowel overlap each other, they may occasionally produce the mistaken impression that you are seeing both sides of the bowel wall (Fig. 15-8).

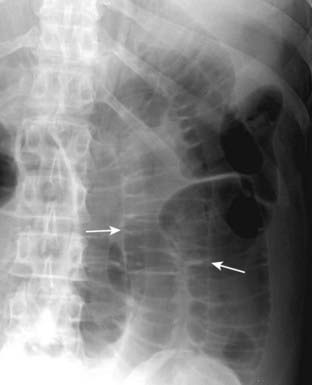

Figure 15-8 Overlapping loops mimicking free air.

Don’t let overlapping loops of dilated small bowel (solid white arrows) fool you into thinking you are seeing both sides of the bowel wall due to free air. If doubt exists about the presence of free air, confirmation may be obtained through an upright or left lateral decubitus view of the abdomen or a CT scan of the abdomen.

Visualization of the Falciform Ligament

The falciform ligament courses over the free edge of the liver anteriorly just to the right of the upper lumbar spine. It contains a remnant of the obliterated umbilical artery.

The falciform ligament courses over the free edge of the liver anteriorly just to the right of the upper lumbar spine. It contains a remnant of the obliterated umbilical artery. When a relatively large amount of free air is present and the patient is in the supine position, free air may rise over the anterior surface of the liver, surround the falciform ligament, and render it visible.

When a relatively large amount of free air is present and the patient is in the supine position, free air may rise over the anterior surface of the liver, surround the falciform ligament, and render it visible. Visualization of the falciform ligament is aptly called the falciform ligament sign and is a sign of free air (Fig. 15-9).

Visualization of the falciform ligament is aptly called the falciform ligament sign and is a sign of free air (Fig. 15-9). The curvilinear appearance of the falciform ligament, combined with the oval-shaped collection of air that collects beneath and distends the abdominal wall, has been likened to the appearance of a football with its laces and is called the football sign.

The curvilinear appearance of the falciform ligament, combined with the oval-shaped collection of air that collects beneath and distends the abdominal wall, has been likened to the appearance of a football with its laces and is called the football sign.

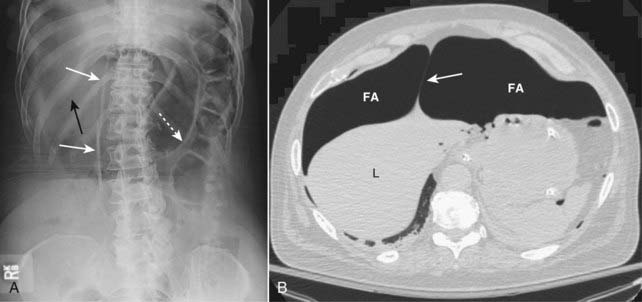

Figure 15-9 Falciform ligament sign.

A, Free intraperitoneal air may surround the normally invisible falciform ligament on the anterior edge of the liver causing that thin, soft tissue structure to become visible (solid white arrows) just to the right of the upper lumbar spine. Notice also that both sides of the stomach wall are visible (Rigler sign) (dotted white arrow) and there is increased lucency in the right upper quadrant (solid black arrow) in this patient with a large pneumoperitoneum from a perforated gastric ulcer. B, The falciform ligament (solid white arrow) is outlined by free air (FA) on either side of it, anterior to the liver (L).

TABLE 15-1 THREE SIGNS OF FREE AIR

| Sign | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Air beneath diaphragm | Requires patient to be in the upright or left lateral decubitus position and a horizontal x-ray beam unless massive in amount |

| Visualization of both sides of the bowel wall | Usually requires large amount of free air; will be visible in any position |

| Visualization of the falciform ligament | Usually requires large amounts of free air; patient is usually supine |

Causes Of Free Air

The most common cause of free intraperitoneal air is rupture of an air-containing loop of bowel, either stomach, small, or large bowel.

The most common cause of free intraperitoneal air is rupture of an air-containing loop of bowel, either stomach, small, or large bowel.

![]() Perforated peptic ulcer is the most common cause of a perforated stomach or duodenum and is still the most common cause of free air.

Perforated peptic ulcer is the most common cause of a perforated stomach or duodenum and is still the most common cause of free air.

Trauma, whether iatrogenic or accidental, can also produce free air.

Trauma, whether iatrogenic or accidental, can also produce free air.

Signs Of Extraperitoneal Air (Retroperitoneal Air)

Unlike the collections of free intraperitoneal air that outline loops of bowel and usually move freely in the abdomen, extraperitoneal air can be recognized by certain other characteristics:

Unlike the collections of free intraperitoneal air that outline loops of bowel and usually move freely in the abdomen, extraperitoneal air can be recognized by certain other characteristics:

Extraperitoneal air may extend through a diaphragmatic hiatus into the mediastinum (and produce pneumomediastinum) or may extend to the peritoneal cavity through openings in the peritoneum (and produce pneumoperitoneum).

Extraperitoneal air may extend through a diaphragmatic hiatus into the mediastinum (and produce pneumomediastinum) or may extend to the peritoneal cavity through openings in the peritoneum (and produce pneumoperitoneum).

Figure 15-10 Extraperitoneal air seen on CT.

Air is seen in the retroperitoneum (solid black arrow) on this axial CT scan of the upper abdomen. Air outlines the inferior vena cava (solid white arrow) and the aorta (dotted white arrow). Unlike free air, extraperitoneal air is streaky, relatively fixed in position, and outlines extraperitoneal structures such as the vena cava, aorta, psoas muscles, and kidneys.

Causes Of Extraperitoneal Air

Signs Of Air In The Bowel Wall

Air in the bowel wall is most easily recognized when it is seen in profile producing a linear radiolucency (black line) whose contour exactly parallels the bowel lumen (Fig. 15-11).

Air in the bowel wall is most easily recognized when it is seen in profile producing a linear radiolucency (black line) whose contour exactly parallels the bowel lumen (Fig. 15-11). Air in the bowel wall seen en face is more difficult to recognize but frequently has a mottled appearance that resembles gas mixed with fecal material (Fig. 15-12).

Air in the bowel wall seen en face is more difficult to recognize but frequently has a mottled appearance that resembles gas mixed with fecal material (Fig. 15-12).

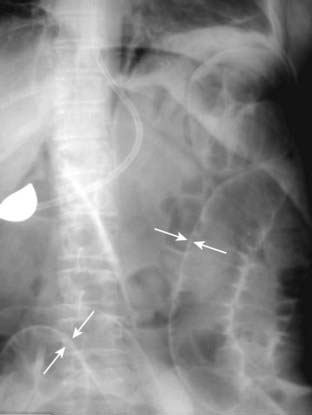

Figure 15-11 Pneumatosis seen in profile.

Close-up of the right lower quadrant in an infant demonstrates a thin curvilinear lucency that parallels the lumen of the adjacent bowel (solid white arrows), an appearance characteristic of gas in the bowel wall seen in profile. In infants, the most common cause for this finding is necrotizing enterocolitis, a disease found mostly in premature infants in which the terminal ileum is most affected. Pneumatosis intestinalis is pathognomonic for necrotizing enterocolitis in infants.

Figure 15-12 Pneumatosis seen en face.

Close-up of the right lower quadrant in another infant shows multiple faint, mottled lucencies in the right lower quadrant (white circle), which is the appearance of pneumatosis intestinalis when seen en face. The density has the same appearance as air mixed with stool, but can be distinguished from stool because it occurs in areas stool might not be expected and it does not change over time. This infant also had necrotizing enterocolitis.

TABLE 15-2 SIGNS OF AIR IN THE BOWEL WALL

| Sign | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Linear radiolucency paralleling the contour of air in the adjacent bowel lumen | Occurs when the air is seen in profile |

| Mottled appearance that resembles air mixed with fecal material | May occur in an area of the abdomen not expected to contain colon; won’t change over time |

| Globular, cystlike collections of air that parallel the contour of the bowel | Unusual, benign condition usually affecting left side of colon |

Causes And Significance Of Air In The Bowel Wall

Pneumatosis intestinalis can be divided into two major categories.

Pneumatosis intestinalis can be divided into two major categories.

Figure 15-13 Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis.

Axial CT scan of the upper abdomen windowed for lung technique shows a cluster of air-containing cysts (solid white arrows) associated with the left colon, characteristic of pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis, a rare but benign condition in which air-containing cysts form in the submucosa or serosa of the bowel.

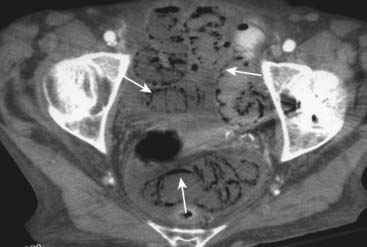

Figure 15-14 Necrosis of bowel from mesenteric ischemia.

Axial CT image of the pelvis demonstrates multiple loops of bowel with punctate collections of air throughout their walls consistent with pneumatosis (solid white arrows). The patient had widespread ischemia of bowel from mesenteric vascular disease. Pneumatosis that results from bowel necrosis is an ominous sign.

![]() Pneumatosis intestinalis associated with diseases that produce necrosis of bowel is usually a more ominous prognostic sign than pneumatosis associated with obstructing lesions of the bowel or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Pneumatosis intestinalis associated with diseases that produce necrosis of bowel is usually a more ominous prognostic sign than pneumatosis associated with obstructing lesions of the bowel or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

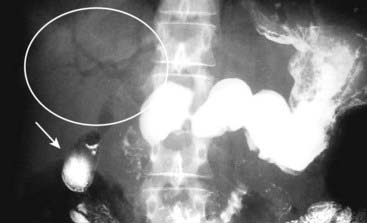

Figure 15-15 Portal venous gas.

A, Numerous small black branching structures are visible over the periphery of the liver (white circle). This is air in the portal venous system, a finding most often associated with necrotizing enterocolitis in infants but which can also be seen in adults, usually with bowel necrosis. Unlike air in the biliary system, this air is peripheral rather than central and has numerous branching structures rather than the few tubular structures seen with pneumobilia. B, Close-up of axial CT scan through the liver shows air in the portal venous system (solid white arrows) in a patient with mesenteric vascular disease.

Signs Of Air In The Biliary System

Air in the biliary system presents as one or two tubelike, branching lucencies in the right upper quadrant overlying the central portion of the liver which conform to the location and appearance of the major bile ducts: the common duct, cystic duct, and the hepatic ducts (Fig. 15-16).

Air in the biliary system presents as one or two tubelike, branching lucencies in the right upper quadrant overlying the central portion of the liver which conform to the location and appearance of the major bile ducts: the common duct, cystic duct, and the hepatic ducts (Fig. 15-16).

Figure 15-16 Air in the biliary tree.

Frontal view of the upper abdomen from an upper gastrointestinal series demonstrates several air-containing tubular structures over the central portion of the liver consistent with air in the biliary system (white circle). There is also barium present in the gallbladder (solid white arrow). This patient had a history of a prior sphincterotomy for gallstones so that reflux of air and barium into the biliary system would be expected.

Causes Of Air In The Biliary System

Gas in the biliary system may be a “normal” finding if the sphincter of Oddi, which guards the entrance of the common bile duct as it enters the duodenum, is open (said to be incompetent).

Gas in the biliary system may be a “normal” finding if the sphincter of Oddi, which guards the entrance of the common bile duct as it enters the duodenum, is open (said to be incompetent). Prior sphincterotomy, such as might be done to allow gallstones to exit from the ductal system into the bowel.

Prior sphincterotomy, such as might be done to allow gallstones to exit from the ductal system into the bowel. Prior surgery that results in the reimplantation of the common bile duct into another part of the bowel (i.e., choledocho-enterostomy) is frequently accompanied by gas in the biliary ductal system.

Prior surgery that results in the reimplantation of the common bile duct into another part of the bowel (i.e., choledocho-enterostomy) is frequently accompanied by gas in the biliary ductal system. Pathologic conditions that can produce pneumobilia include uncommon causes:

Pathologic conditions that can produce pneumobilia include uncommon causes:

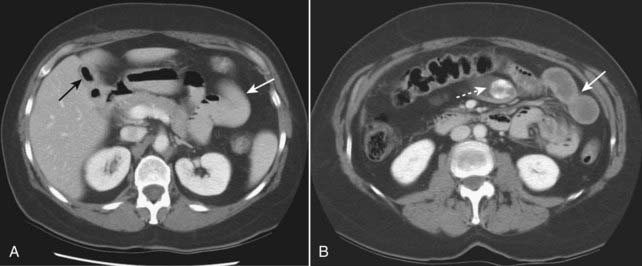

![]() Gallstone ileus—in which a gallstone erodes through the wall of the gallbladder into the duodenum, usually producing a fistula between the bowel and the biliary system.

Gallstone ileus—in which a gallstone erodes through the wall of the gallbladder into the duodenum, usually producing a fistula between the bowel and the biliary system.

The three key findings of gallstone ileus are present on this study. A, Axial CT scan of the upper abdomen shows air in the lumen of the gallbladder (solid black arrow) and dilated small bowel (solid white arrow) consistent with a mechanical small bowel obstruction. At a lower level, another axial CT scan of the abdomen (B) shows a large calcified gallstone inside the small bowel (dotted white arrow) and additional proximal, dilated loops of small bowel (solid white arrow). The gallstone had eroded through the wall of the gallbladder into the duodenum and then began a journey down the small bowel before becoming impacted and producing obstruction.

Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Recognizing Extraluminal Air in the Abdomen on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Recognizing Extraluminal Air in the Abdomen

Gas in the abdomen outside of the normal confines of the bowel is called extraluminal air.

The four most common locations for extraluminal air are intraperitoneal (pneumoperitoneum—frequently called free air), retroperitoneal air, air in the bowel wall (pneumatosis), and air in the biliary system (pneumobilia).

The three key signs of pneumoperitoneum are air beneath the diaphragm, visualization of both sides of the bowel wall (Rigler sign), and visualization of the falciform ligament.

The most common causes of free air are perforated peptic ulcer, trauma whether accidental or iatrogenic, and perforated diverticulitis. Perforated appendicitis and perforation of a carcinoma, usually of the colon, are rare causes of free air.

The key signs of extraperitoneal (retroperitoneal) air are a streaky, linear appearance or a mottled, blotchy appearance outlining extraperitoneal structures and its relatively fixed position, moving little or not at all with changes in patient positioning.

Extraperitoneal air outlines extraperitoneal structures such as the psoas muscles, kidneys, aorta, and inferior vena cava.

Causes of extraperitoneal air include bowel perforation secondary to either inflammatory or ulcerative disease, blunt or penetrating trauma, iatrogenic manipulation, and foreign body ingestion.

The key signs of air in the bowel wall include linear radiolucencies paralleling the contour of air in the adjacent bowel lumen, a mottled appearance that resembles air mixed with fecal material, or uncommonly, globular, cystlike collections of air that parallel the contour of the bowel.

Causes of air in the bowel wall (pneumatosis intestinalis) include a rare primary form called pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis and a more common secondary form that includes diseases in which there is necrosis of the bowel wall such as necrotizing enterocolitis in infants and ischemic bowel disease in adults, as well as obstructing lesions of the bowel which raise intraluminal pressure such as Hirschsprung disease in children and obstructing carcinomas in adults.

Pneumatosis intestinalis associated with diseases that produce necrosis of bowel is usually a more ominous prognostic sign than pneumatosis associated with obstructing lesions of the bowel or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Signs of air in the biliary system include tubelike, branching lucencies in the right upper quadrant overlying the liver, which are central in location and few in number, and gas in the lumen of the gallbladder.

Causes of pneumobilia include incompetence of the sphincter of Oddi, prior sphincterotomy, prior surgery that results in the reimplantation of the common bile duct into another part of the bowel, and gallstone ileus.

The three findings in gallstone ileus are air in the biliary system, small bowel obstruction, and visualization of the gallstone itself.