Chapter 13 Recognizing the Normal Abdomen

Conventional Radiographs

While imaging of the abdomen is now largely performed utilizing CT, ultrasound, or MRI, many patients have “plain films” of the abdomen as a first step before other imaging studies are performed or as a method of following up on findings demonstrated by other modalities.

While imaging of the abdomen is now largely performed utilizing CT, ultrasound, or MRI, many patients have “plain films” of the abdomen as a first step before other imaging studies are performed or as a method of following up on findings demonstrated by other modalities.

In order to recognize abnormal findings on conventional radiographs of the abdomen, you first must familiarize yourself with the appearance of normal.

In order to recognize abnormal findings on conventional radiographs of the abdomen, you first must familiarize yourself with the appearance of normal.What To Look For

![]() First, look at the overall gas pattern (Box 13-1).

First, look at the overall gas pattern (Box 13-1).

Normal Bowel Gas Pattern

Virtually all gas in the bowel comes from swallowed air. Only a fraction comes from the bacterial fermentation of food.

Virtually all gas in the bowel comes from swallowed air. Only a fraction comes from the bacterial fermentation of food. In the abdomen, the terms gas and air are used interchangeably to refer to the contents of the bowel.

In the abdomen, the terms gas and air are used interchangeably to refer to the contents of the bowel. Loops of bowel that contain a sufficient amount of air to fill the lumen completely are said to be distended. Distension of bowel is normal.

Loops of bowel that contain a sufficient amount of air to fill the lumen completely are said to be distended. Distension of bowel is normal. Loops of bowel that are filled beyond their normal size are said to be dilated. Dilatation of the bowel is abnormal.

Loops of bowel that are filled beyond their normal size are said to be dilated. Dilatation of the bowel is abnormal. Small bowel

Small bowel

Large bowel

Large bowel

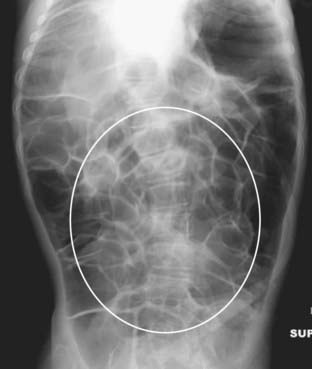

Figure 13-1 Normal supine abdomen.

This is the “scout” film of the abdomen, the one that gives a general idea of the bowel gas pattern and allows you to search for radiopaque calculi and detect organomegaly. There is usually a small amount of air in about two to three loops of nondilated small bowel (solid black arrow). There will almost always be air in the stomach (dotted black arrow) and in the rectosigmoid (solid white arrow). Depending on the amount of fat around the visceral organs, their outlines may be partially visible on conventional radiographs. The psoas muscles are outlined by fat (dotted white arrows) making them visible on this image.

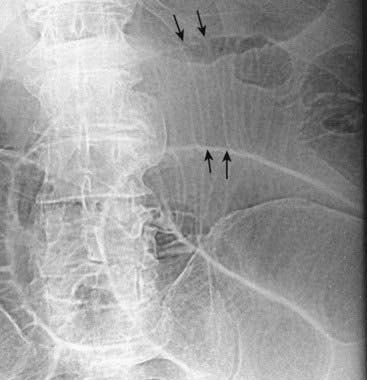

Figure 13-2 Normal prone abdomen.

In the prone position, the ascending and descending colon and the rectosigmoid—all posterior structures—are the highest parts of the large bowel and thus most likely to fill with air. There is air seen in the S-shaped rectosigmoid (solid black arrow) and throughout the remainder of the colon (solid white arrows).

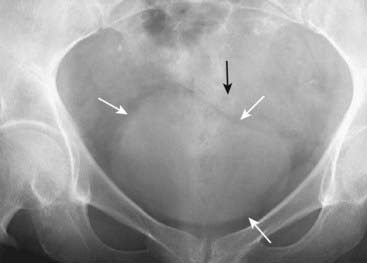

Figure 13-3 Normal colonic distension.

The colon can normally distend to the size of the diameter of the colon as seen on a barium enema (solid white arrows). Beyond this size, the colon would be considered dilated. This patient has had a double-contrast barium enema examination in which both air and barium are instilled as contrast agents. The combination allows for excellent visualization of the mucosal surface of the colon.

Figure 13-4 Appearance of stool.

Stool is recognizable by the multiple, small bubbles of gas present within a semisolid-appearing soft tissue density (white circle). Stool marks the location of the large bowel and can help in identification of individual loops of bowel on conventional radiographs. This patient has a markedly dilated sigmoid colon from chronic constipation.

![]() Individuals who swallow large quantities of air may develop aerophagia, characterized by numerous polygonal-shaped, air-containing loops of bowel, none of which is dilated (Fig. 13-5).

Individuals who swallow large quantities of air may develop aerophagia, characterized by numerous polygonal-shaped, air-containing loops of bowel, none of which is dilated (Fig. 13-5).

Normal Fluid Levels

Stomach

Stomach

Large bowel

Large bowel

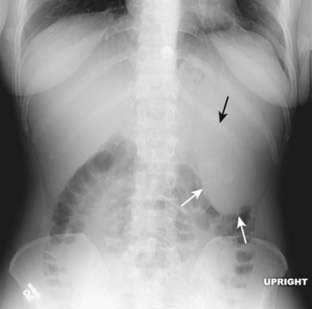

Figure 13-6 Normal upright abdomen.

There for two things to look for on an upright view of the abdomen: air-fluid levels and free intraperitoneal air. Normally, there is an air-fluid level in the stomach (solid black arrow). There may be short, air-fluid levels present in a few nondilated loops of small bowel (black circle). There are usually very few or no air-fluid levels seen in the colon. Free air, if present, should be visible just below the hemidiaphragm (dotted black arrow) and would be easier to recognize on the right than on the left.

![]() Many air-fluid levels may be present in the colon if the patient has had a recent enema or if the patient is taking medication with a strong anticholinergic, antiperistaltic effect.

Many air-fluid levels may be present in the colon if the patient has had a recent enema or if the patient is taking medication with a strong anticholinergic, antiperistaltic effect.

TABLE 13-1 NORMAL DISTRIBUTION OF GAS AND FLUID IN THE ABDOMEN

| Organ | Normally Contains Gas | Normally Has Air-Fluid Levels |

|---|---|---|

| Stomach | Yes | Yes |

| Small bowel | Yes—2-3 loops | Yes |

| Large bowel | Yes, especially rectosigmoid | No |

Differentiating Large From Small Bowel

Recognizing large bowel

Recognizing large bowel

Recognizing small bowel

Recognizing small bowel

Figure 13-7 Location of large bowel.

The large bowel usually occupies the periphery of the abdomen. The small bowel is located more centrally. Here, the large bowel (solid black arrows) contains a normal amount of air. The liver occupies the right upper quadrant and normally displaces all bowel from this area.

Figure 13-8 Normal large bowel haustral markings.

Most haustral markings in the colon do not traverse the entire lumen to extend from one wall to the opposite wall (solid white arrows). This is unlike the appearance of the valvulae conniventes in the small bowel. The haustral markings are also spaced more widely apart than the valvulae of the small bowel (see Fig. 13-9).

Figure 13-9 Normal small bowel valvulae.

Markings representing the valvulae typically do extend across the lumen of the small bowel to extend from one wall to the other. In addition, the valvulae are spaced much closer together than the haustra of the large bowel, even when the small bowel is dilated. The solid black arrows point to two valvulae that traverse the entire lumen in this enhanced close-up of dilated small bowel in this patient with a small bowel obstruction.

Acute Abdominal Series: The Views And What They Show

Almost every Department of Radiology has a series of radiographic images (a protocol) that is routinely obtained in patients who have acute abdominal pain.

Almost every Department of Radiology has a series of radiographic images (a protocol) that is routinely obtained in patients who have acute abdominal pain.

Acute abdominal series: what it may contain

Acute abdominal series: what it may contain

TABLE 13-2 ACUTE ABDOMINAL SERIES: THE VIEWS AND WHAT TO LOOK FOR

| View | Look for |

|---|---|

| Supine abdomen | Bowel gas pattern, calcifications, masses |

| Prone abdomen | Gas in the rectosigmoid |

| Upright abdomen | Free air, air-fluid levels in the bowel |

| Upright chest | Free air, pneumonia, pleural effusions |

Acute Abdominal Series: Supine View (“Scout Film”)

How it’s obtained

How it’s obtained

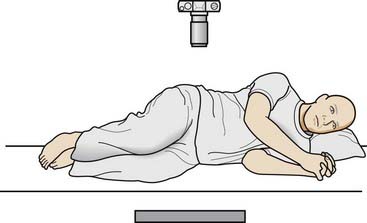

Figure 13-10 Positioning for supine view of the abdomen.

The patient lies on his or her back on the x-ray table or stretcher and the x-ray beam is directed vertically downward. The camera icon represents the x-ray tube, which would actually be positioned about 40 inches above the cassette, represented by the thick line.

Acute Abdominal Series: Prone View

What it’s good for

What it’s good for

How it’s obtained

How it’s obtained

Substitute view

Substitute view

Figure 13-11 Positioning for prone view of the abdomen.

The patient lies on his or her abdomen on the x-ray table or stretcher and the x-ray beam is directed vertically downward. The camera icon represents the x-ray tube, which would actually be positioned about 40 inches above the cassette, represented by the thick line.

Figure 13-12 Positioning for the lateral rectum view.

Patients who cannot lie prone can turn on their left side and have a lateral view of the rectum exposed with a vertical beam to substitute for the prone radiograph. The camera icon represents the x-ray tube, which would actually be positioned about 40 inches above the cassette, represented by the thick line.

Figure 13-13 Normal lateral view of the rectum.

Frequently, patients are unable to lie prone because of their physical condition (e.g., recent surgery, severe abdominal pain). These patients can turn on their left side and have a lateral view of the rectum exposed with a vertical beam to substitute for the prone radiograph. The lateral view of the rectum will usually demonstrate the presence or absence of air in the rectum and sigmoid (solid black arrow).

Acute Abdominal Series: Upright View of Abdomen

How it’s obtained

How it’s obtained

Substitute view

Substitute view

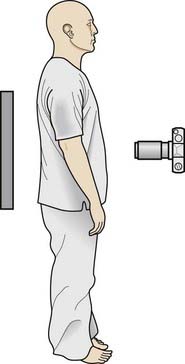

Figure 13-14 Positioning of patient for an upright view of the abdomen.

The patient stands or sits up and the x-ray beam is directed horizontally, parallel to the plane of the floor. The camera icon represents the x-ray tube, which would actually be positioned about 40 inches from the cassette, represented by the thick line.

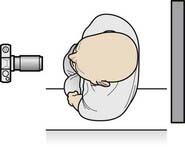

Figure 13-15 Positioning of the patient for a left lateral decubitus view of the abdomen.

Patients who cannot tolerate an upright view of their abdomen usually have a left lateral decubitus view as a substitute. The patient lies on his or her left side on the examining table, the x-ray tube is usually positioned anteriorly (camera icon) and the cassette (thick line) is placed in back of the patient. The x-ray beam is directed horizontally, parallel to the floor at a distance of about 40 inches from the patient.

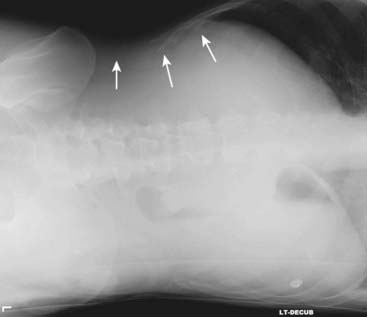

Figure 13-16 Normal left lateral decubitus view of the abdomen.

For a left lateral decubitus view, the patient lies on his or her left side on the examining table and an exposure is made with a horizontal x-ray beam (parallel to the floor). This is done so that any “free air” will distribute itself at the highest part of the abdominal cavity which will be the patient’s right side. Free air, if present, should be easily visible as a black crescent over the outside edge of the liver (solid white arrows), a location in which no bowel gas is normally present.

![]() Box 13-2 summarizes what is needed to visualize air-fluid levels in the abdomen.

Box 13-2 summarizes what is needed to visualize air-fluid levels in the abdomen.

Acute Abdominal Series: Upright View of Chest

What it’s good for

What it’s good for

How it’s obtained

How it’s obtained

Calcifications

![]() Abdominal calcifications are discussed in Chapter 16, Recognizing Abnormal Calcifications. There are two abdominal calcifications that should not be confused with pathologic calcifications.

Abdominal calcifications are discussed in Chapter 16, Recognizing Abnormal Calcifications. There are two abdominal calcifications that should not be confused with pathologic calcifications.

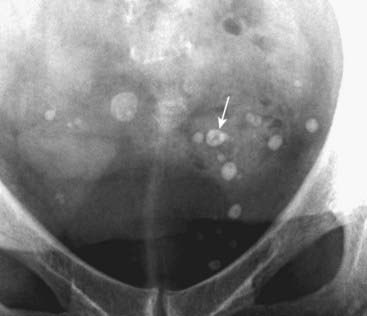

Phleboliths are small, rounded calcifications that represent calcified venous thrombi that occur with increasing age, most often in the pelvic veins of women. They classically have a lucent center, which helps to differentiate them from ureteral calculi with which phleboliths can be confused (Fig. 13-18).

Phleboliths are small, rounded calcifications that represent calcified venous thrombi that occur with increasing age, most often in the pelvic veins of women. They classically have a lucent center, which helps to differentiate them from ureteral calculi with which phleboliths can be confused (Fig. 13-18). Calcification of the rib cartilages occurs with advancing age and, while not a true abdominal calcification, can sometimes be confused for renal or biliary calculi when they overlie the kidney or region of the gallbladder. Calcified cartilage tends to have an amorphous, speckled appearance and the calcified cartilage will occur in an arc corresponding to that of the anterior rib cartilage as it sweeps back towards the sternum (Fig. 13-19).

Calcification of the rib cartilages occurs with advancing age and, while not a true abdominal calcification, can sometimes be confused for renal or biliary calculi when they overlie the kidney or region of the gallbladder. Calcified cartilage tends to have an amorphous, speckled appearance and the calcified cartilage will occur in an arc corresponding to that of the anterior rib cartilage as it sweeps back towards the sternum (Fig. 13-19).

Phleboliths are small, rounded calcifications that represent calcified venous thrombi that occur with increasing age, most often in the pelvic veins of women. They classically have a lucent center (solid white arrow). In the pelvic veins, they are considered incidental and nonpathologic calcifications, but they can be confused with ureteral calculi.

Figure 13-19 Calcified rib cartilages.

Calcification of the rib cartilages (white circle) occurs with advancing age and, while not a true abdominal calcification, can sometimes be confused for calculi when it overlies the kidney or region of the gallbladder. Calcified cartilage tends to have an amorphous, mottled appearance. Calcified rib cartilages will occur along an arc corresponding to the sweep of the anterior ribs as they turn back toward the sternum.

Organomegaly

Conventional radiographic evaluation of soft tissue structures in the abdomen (e.g., the liver, spleen, kidneys, gallbladder, urinary bladder, or soft tissue masses such as tumors or abscesses) is limited because these structures are soft tissue densities and they are surrounded by other soft tissues or fluid of similar density.

Conventional radiographic evaluation of soft tissue structures in the abdomen (e.g., the liver, spleen, kidneys, gallbladder, urinary bladder, or soft tissue masses such as tumors or abscesses) is limited because these structures are soft tissue densities and they are surrounded by other soft tissues or fluid of similar density.

Still, conventional radiographs are easy to obtain and frequently the first study ordered in a patient with abdominal symptoms.

Still, conventional radiographs are easy to obtain and frequently the first study ordered in a patient with abdominal symptoms.

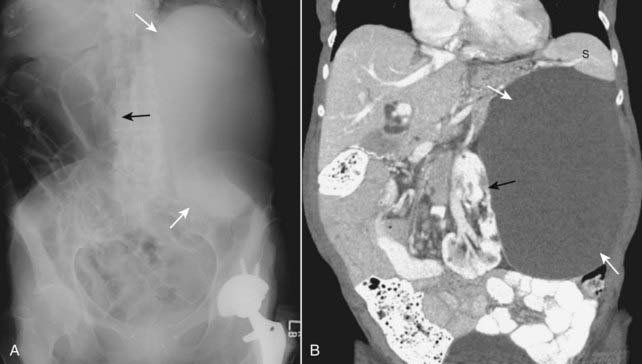

![]() There are two fundamental ways of recognizing the presence and estimating the size of soft tissue masses or organs on conventional radiographs of the abdomen:

There are two fundamental ways of recognizing the presence and estimating the size of soft tissue masses or organs on conventional radiographs of the abdomen:

Liver

Normal

Normal

Enlarged liver

Enlarged liver

Figure 13-20 Riedel lobe of the liver.

Occasionally, a tonguelike projection of the right lobe of the liver may extend to the iliac crest, especially in females. This is called a Riedel lobe and is normal (solid black arrows). Conventional radiographs are notoriously poor for estimating the size of the liver; CT, MRI, or US give a more accurate picture of liver size.

Sometimes, the liver can become so enlarged it will be obvious even on conventional radiographs. An enlarged liver might be suggested from conventional radiographs if there is displacement of all bowel loops from the right upper quadrant down to the iliac crest and across the midline (solid black arrows), as in this patient with cirrhosis.

Spleen

Normal

Normal

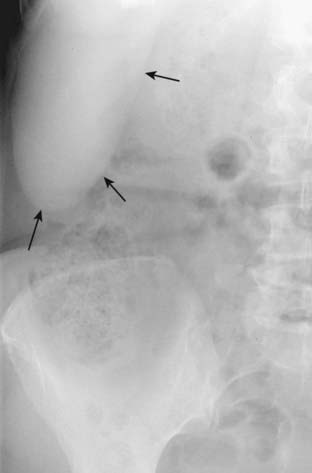

Enlarged spleen

Enlarged spleen

The spleen is about 12 cm in length and usually does not project below the 12th posterior rib. If the spleen (solid white arrows) projects well below the 12th posterior rib (solid black arrow) or displaces the stomach bubble toward or across the midline, the spleen is probably enlarged, as it is in this patient with leukemia.

Kidneys

Normal

Normal

Enlarged kidney

Enlarged kidney

Figure 13-23 Position of the kidneys.

This is one image from an intravenous urogram (intravenous pyelogram [IVP]) in which the patient receives an intravenous injection of iodinated contrast which is excreted by the kidneys. Both kidney outlines (solid white arrows), ureters (solid black arrows) and urinary bladder (dotted black arrow) can be seen. Other images of the kidneys, including oblique views, were often obtained to visualize the entire contour of the kidney. CT scans and CT urograms have largely replaced IVPs. The liver (dotted white arrow) normally depresses the right kidney more inferior than the left kidney.

Soft tissue masses or organomegaly can be diagnosed from a conventional radiograph either by visualizing the edge of the mass if there is fat or air surrounding it or by displacement of bowel. A, On the conventional radiograph, there is a soft tissue mass in the left upper quadrant (solid white arrows), which is displacing bowel to the right (solid black arrow). B, A coronal reformatted CT scan of the same patient demonstrates a large renal cyst (solid white arrows) arising from the left kidney (solid black arrow), displacing it and the surrounding bowel. The cyst is compressing the spleen (S).

Urinary Bladder

Normal

Normal

Enlarged urinary bladder

Enlarged urinary bladder

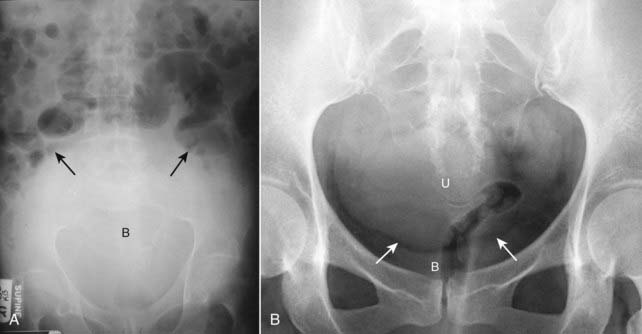

Figure 13-25 Normal urinary bladder.

Close-up of the pelvis shows enough perivesical fat to make the outline of the urinary bladder visible (solid white arrows). In males, the sigmoid colon usually occupies the space just above the bladder (solid black arrow); in females, the soft tissue above the bladder may be either the uterus or sigmoid colon.

Figure 13-26 Distended urinary bladder and enlarged uterus.

A, The distended bladder (B) is a soft tissue mass that ascends from the pelvis into the lower abdomen displacing the bowel into the midabdomen (solid black arrows). This was a 72-year-old man with bladder outlet obstruction from benign prostatic hypertrophy. B, The uterus (U) is slightly enlarged. It can be distinguished from the bladder because there is a fat plane (solid white arrows) seen between it and the urinary bladder (B) below it.

Uterus

Enlarged uterus

Enlarged uterus

Psoas Muscles

One or both of them may be visible if there is adequate extraperitoneal fat surrounding them. Inability to visualize one or both psoas muscles is not a reliable indicator of retroperitoneal disease (see Fig. 13-1).

One or both of them may be visible if there is adequate extraperitoneal fat surrounding them. Inability to visualize one or both psoas muscles is not a reliable indicator of retroperitoneal disease (see Fig. 13-1). Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Recognizing the Normal Abdomen: Conventional Radiographs on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Recognizing the Normal Abdomen: Conventional Radiographs

Evaluation of the abdomen should focus on four main areas: the gas pattern, free air, soft tissue masses or organomegaly, and abnormal calcifications.

Air is normally present in the stomach and colon, especially the rectosigmoid, while a small amount of air (2-3 loops) may be seen in normal small bowel.

An air-fluid level is found normally in the stomach; two or three air fluid levels may be seen in nondilated small bowel, but usually no fluid is visible in the colon.

An acute abdominal series usually consists of: supine abdomen, prone abdomen (or its substitute, a lateral rectum view), upright abdomen (or its substitute, a left lateral decubitus view), and an upright chest (or its substitute, a supine chest).

The supine view of the abdomen is the general scout view for the bowel gas pattern and is useful for seeing calcifications and detecting organomegaly or soft tissue masses.

The prone view allows air, if present, to be seen in the rectosigmoid, which is important in the evaluation of mechanical obstruction of the bowel.

The upright abdomen may demonstrate air-fluid levels in the bowel or free intraperitoneal air.

The upright chest radiograph may demonstrate free air beneath the diaphragm, pleural effusion (which may provide a clue as to the presence and the nature of intraabdominal pathology), or pneumonia (which can mimic an acute abdomen).

CT, US, and MRI have essentially replaced conventional radiography in the assessment of organomegaly or soft tissue masses.