Chapter 21 Recognizing Abnormalities of Bone Density

Normal Bone Anatomy

Conventional Radiography

On conventional radiographs, bones consist of a dense cortex of compact bone, which completely envelopes a less dense medullary cavity containing cancellous bone arranged as trabeculae, separated primarily by blood vessels, hematopoietic cells, and fat. The proportions of cortical versus trabecular bone vary in different skeletal sites and even at different locations in the same bone, i.e., the cortex is naturally thicker in some places than in others.

On conventional radiographs, bones consist of a dense cortex of compact bone, which completely envelopes a less dense medullary cavity containing cancellous bone arranged as trabeculae, separated primarily by blood vessels, hematopoietic cells, and fat. The proportions of cortical versus trabecular bone vary in different skeletal sites and even at different locations in the same bone, i.e., the cortex is naturally thicker in some places than in others. When viewed in tangent on conventional radiographs, the cortex produces a smooth white shell of varying thickness that appears as a dense white band along the outer margins of the bone.

When viewed in tangent on conventional radiographs, the cortex produces a smooth white shell of varying thickness that appears as a dense white band along the outer margins of the bone. The medullary cavity on conventional radiographs appears as a core of less dense, grayish material inside the cortical shell, interlaced with a fine network of bony trabecular markings. The corticomedullary junction is the edge between the inner margin of the cortex and the medullary cavity (Fig. 21-1).

The medullary cavity on conventional radiographs appears as a core of less dense, grayish material inside the cortical shell, interlaced with a fine network of bony trabecular markings. The corticomedullary junction is the edge between the inner margin of the cortex and the medullary cavity (Fig. 21-1). It is important to remember that the cortex completely surrounds the entire bone but on conventional radiographs is best seen where it is viewed in profile, i.e., where the x-ray beam passes tangentially to the bone.

It is important to remember that the cortex completely surrounds the entire bone but on conventional radiographs is best seen where it is viewed in profile, i.e., where the x-ray beam passes tangentially to the bone. Almost all examinations of bone start with conventional radiographs obtained with at least two views exposed at a 90° angle to each other (called orthogonal views) so as to localize abnormalities better and to visualize as much of the circumference of the bone as possible.

Almost all examinations of bone start with conventional radiographs obtained with at least two views exposed at a 90° angle to each other (called orthogonal views) so as to localize abnormalities better and to visualize as much of the circumference of the bone as possible.

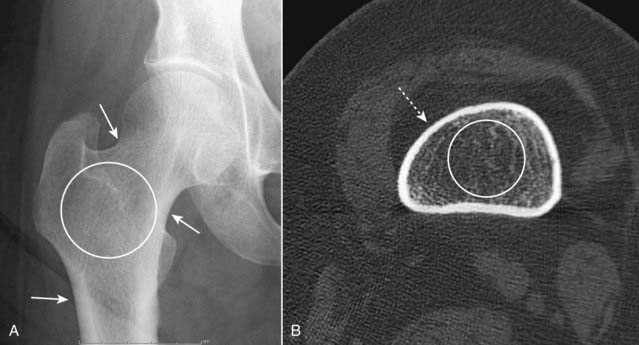

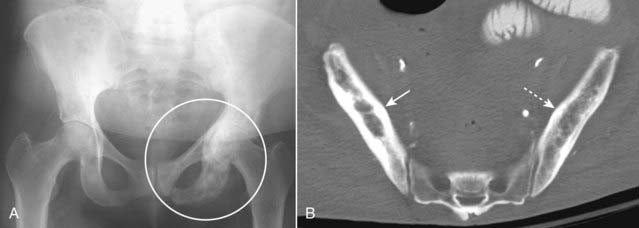

Figure 21-1 Normal appearance of bone.

A, This is an anteroposterior view of the hip. When viewed in tangent, the cortex is seen as a white line, varying in thickness in different parts of the bone (solid white arrows). In the medullary cavity, cancellous bone is seen to contain an interlacing network of trabeculae (white circle). B, An axial CT scan through the proximal femur. The entire 360° circumference of the cortex (dotted white arrow) is seen surrounding the less-dense medullary cavity containing both bony trabeculae and fat (white circle). The image is optimized to display bone so that the muscles and subcutaneous fat are less well seen.

CT and MRI

CT and MRI are able to demonstrate the entire circumference and internal matrix of bone, including, especially with MRI, surrounding soft tissues not visible on conventional radiographs. This is accomplished by computer-aided reformatting and a superior ability to display more subtle differences in tissue densities (Fig. 21-2).

CT and MRI are able to demonstrate the entire circumference and internal matrix of bone, including, especially with MRI, surrounding soft tissues not visible on conventional radiographs. This is accomplished by computer-aided reformatting and a superior ability to display more subtle differences in tissue densities (Fig. 21-2). In addition to bony trabeculae, the marrow cavity contains red and yellow bone marrow. The red marrow produces the precursors of blood cells. Yellow marrow contains fat. The composition of marrow is different for different bones of the body and changes during life to become less hematopoietically active with age so that, around age 30, most of the appendicular skeleton contains only yellow marrow while most of the red marrow resides in the axial skeleton. Unlike conventional radiography, MRI is an excellent means of studying the components of marrow, a fact that makes MRI so useful in the study of marrow pathology.

In addition to bony trabeculae, the marrow cavity contains red and yellow bone marrow. The red marrow produces the precursors of blood cells. Yellow marrow contains fat. The composition of marrow is different for different bones of the body and changes during life to become less hematopoietically active with age so that, around age 30, most of the appendicular skeleton contains only yellow marrow while most of the red marrow resides in the axial skeleton. Unlike conventional radiography, MRI is an excellent means of studying the components of marrow, a fact that makes MRI so useful in the study of marrow pathology. Whereas the cortex is the part of the bone most easily visualized on conventional radiographs, cortical bone has a very low signal intensity on conventional MRI sequences.

Whereas the cortex is the part of the bone most easily visualized on conventional radiographs, cortical bone has a very low signal intensity on conventional MRI sequences.

Figure 21-2 Normal MRI of knee.

A sagittal view of the knee demonstrates the superior display of the internal matrix of bone and the surrounding soft tissues. There is fatty marrow in the distal femur (F), proximal tibia (T), and patella (P). The quadriceps (solid black arrow) and patellar (dotted white arrow) tendons are shown. The anterior cruciate ligament (solid white arrow) is visible. There is bright signal fat in the infrapatellar fat pad (FP). Notice how the cortex of bone has a very weak signal (dotted black arrow).

The Effect of Bone Physiology on Bone Anatomy

Bones reflect the general metabolic status of the individual. Their composition requires a protein-containing, collagenous matrix (osteoid) upon which bone mineral, principally calcium phosphate, is transformed into cartilage and bone.

Bones reflect the general metabolic status of the individual. Their composition requires a protein-containing, collagenous matrix (osteoid) upon which bone mineral, principally calcium phosphate, is transformed into cartilage and bone. Bones are continuously undergoing remodeling processes that include resorption of old or diseased bone by osteoclasts and formation of new bone by osteoblasts. While osteoblasts are responsible for bone matrix production, osteoclasts resorb both the matrix and mineral.

Bones are continuously undergoing remodeling processes that include resorption of old or diseased bone by osteoclasts and formation of new bone by osteoblasts. While osteoblasts are responsible for bone matrix production, osteoclasts resorb both the matrix and mineral. Both osteoclastic and osteoblastic activity depend on the presence of a viable blood supply to bring those cells to the bone

Both osteoclastic and osteoblastic activity depend on the presence of a viable blood supply to bring those cells to the bone Bones also respond to mechanical forces—for example, the contractions of muscles and tendons, the process of bearing weight, constant use, or prolonged disuse—that help to form or maintain the shape as well as the content of each bone.

Bones also respond to mechanical forces—for example, the contractions of muscles and tendons, the process of bearing weight, constant use, or prolonged disuse—that help to form or maintain the shape as well as the content of each bone. In this chapter, we arbitrarily divide abnormalities of bone density into two major categories based primarily on their appearance on conventional radiographs—those that produce a pattern of either increased or decreased bone density and then subdivide those two patterns by extent of disease: focal versus diffuse (or generalized) changes (Table 21-1).

In this chapter, we arbitrarily divide abnormalities of bone density into two major categories based primarily on their appearance on conventional radiographs—those that produce a pattern of either increased or decreased bone density and then subdivide those two patterns by extent of disease: focal versus diffuse (or generalized) changes (Table 21-1). If MRI were used as the basis for categorization, bone (marrow) disorders could be divided into four other categories:

If MRI were used as the basis for categorization, bone (marrow) disorders could be divided into four other categories:

TABLE 21-1 CHANGES IN BONE DENSITY

| Density | Extent | Examples Used in this Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Increased Density ↑ |

Diffuse | Diffuse osteoblastic metastases |

| Osteopetrosis (rare) | ||

| Focal | Localized osteoblastic metastases | |

| Avascular necrosis of bone | ||

| Paget disease | ||

| Decreased Density ↓ |

Diffuse | Osteoporosis |

| Hyperparathyroidism | ||

| Rickets and osteomalacia | ||

| Focal | Localized osteolytic metastases | |

| Multiple myeloma | ||

| Osteomyelitis |

Recognizing a Generalized Increase in Bone Density

On conventional radiographs and CT, there will be an overall whiteness (sclerosis) to all or most of the bones.

On conventional radiographs and CT, there will be an overall whiteness (sclerosis) to all or most of the bones. This leads to a diffuse loss of visualization of the normal network of bony trabeculae in the medullary cavity because of replacement of the normal intertrabecular fatty marrow by bone-producing elements.

This leads to a diffuse loss of visualization of the normal network of bony trabeculae in the medullary cavity because of replacement of the normal intertrabecular fatty marrow by bone-producing elements. There is also a loss of visualization of the normal corticomedullary junction because of the abnormally increased density of the medullary cavity relative to the cortex (Fig. 21-3).

There is also a loss of visualization of the normal corticomedullary junction because of the abnormally increased density of the medullary cavity relative to the cortex (Fig. 21-3).

Figure 21-3 Diffuse metastatic disease from carcinoma of the prostate.

The bones are diffusely sclerotic. You can no longer see the normal trabeculae or the junction between the medullary cavity and the cortex as the medullary cavities have been filled in with osteoblastic metastatic disease that obscures these normal boundaries and increases the overall bone density. Contrast this picture with that of Paget disease of the pelvis (see Fig. 21-12).

Carcinoma of the Prostate

Diffuse, blood-borne, metastatic disease from carcinoma of the prostate is the prototype for generalized increase in bone density. Osteoblastic activity occurs beyond the control of normal physiologic constraints.

Diffuse, blood-borne, metastatic disease from carcinoma of the prostate is the prototype for generalized increase in bone density. Osteoblastic activity occurs beyond the control of normal physiologic constraints. Metastatic disease to bone occurs in over 80% of autopsied patients with carcinoma of the prostate. Multiple bone metastases from carcinoma of the prostate occur much more frequently than do solitary bone lesions.

Metastatic disease to bone occurs in over 80% of autopsied patients with carcinoma of the prostate. Multiple bone metastases from carcinoma of the prostate occur much more frequently than do solitary bone lesions. With diffuse bone metastases, a so-called superscan may be seen on radionuclide bone scan. The superscan demonstrates high radiotracer uptake throughout the skeleton, with poor or absent renal excretion of the radiotracer (Fig. 21-4).

With diffuse bone metastases, a so-called superscan may be seen on radionuclide bone scan. The superscan demonstrates high radiotracer uptake throughout the skeleton, with poor or absent renal excretion of the radiotracer (Fig. 21-4).

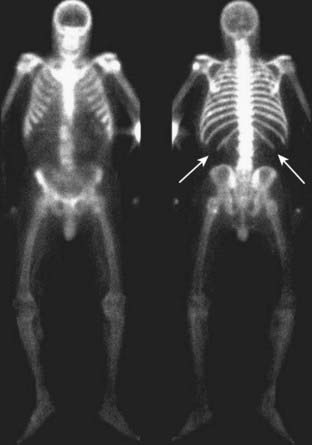

Figure 21-4 Radionuclide bone superscan.

Anterior and posterior views of the axial and appendicular skeleton show the increased distribution of bone radiotracer uptake throughout the skeleton. This is the picture of the so-called superscan produced by osteoblastic metastatic disease involving every bone leading to high uptake throughout the skeleton, with poor or absent renal excretion of the radiotracer (solid white arrows point to the absence of excretion by the kidneys).

Osteopetrosis

Osteopetrosis (also called marble bone disease for obvious reasons) is a rare hereditary defect in osteoclastic activity that ultimately results in an increase in bone density affecting the entire skeleton (Fig. 21-5).

Osteopetrosis (also called marble bone disease for obvious reasons) is a rare hereditary defect in osteoclastic activity that ultimately results in an increase in bone density affecting the entire skeleton (Fig. 21-5). Although the bones are increased in density, they are mechanically inferior to normal bone and are more prone to pathologic fractures.

Although the bones are increased in density, they are mechanically inferior to normal bone and are more prone to pathologic fractures. In the infantile form of this disease, the defective osseous material can replace normal bone marrow leading to anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia (pancytopenia).

In the infantile form of this disease, the defective osseous material can replace normal bone marrow leading to anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia (pancytopenia).

Figure 21-5 Osteopetrosis (marble bone disease).

A frontal view of the pelvis demonstrates diffuse sclerosis of the bones in this 22-year-old patient with osteopetrosis, a rare defect in osteoclastic activity that results in an increase in bone density. Although the bones are dense, they are mechanically inferior to normal bone and subject to pathologic fractures. In the infantile form of this disease, the defective osseous material can replace normal bone marrow leading to anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia (pancytopenia).

Recognizing a Focal Increase in Bone Density

![]() Focal sclerotic lesions can affect the cortex and medullary cavity. Those that affect the cortex will usually produce periosteal new-bone formation (periosteal reaction), which leads to an appearance of thickening of the cortex. Those that affect the medullary cavity will result in punctate, amorphous sclerotic lesions surrounded by the normal medullary cavity (Fig. 21-6).

Focal sclerotic lesions can affect the cortex and medullary cavity. Those that affect the cortex will usually produce periosteal new-bone formation (periosteal reaction), which leads to an appearance of thickening of the cortex. Those that affect the medullary cavity will result in punctate, amorphous sclerotic lesions surrounded by the normal medullary cavity (Fig. 21-6).

Figure 21-6 Focal sclerotic metastases from carcinoma of the prostate.

There are sclerotic lesions seen in the L4 and S1 vertebral bodies (solid white arrows). It is no longer possible to distinguish the junction between the cortex and the medullary cavity in either of those vertebral bodies. Also present are multiple sclerotic lesions in the right ilium (white circle) and scattered throughout the pelvis. Sclerotic lesions in bone are a common finding in carcinoma of the prostate.

Carcinoma of the Prostate

A substance secreted by tumor cells from metastatic carcinoma of the prostate may stimulate osteoblastic activity and produce focal areas of localized increased density, i.e., sclerotic bone lesions. The lesions may also be diffuse. These lesions are most often seen in the vertebrae, ribs, pelvis, humeri, and femora (Fig. 21-7).

A substance secreted by tumor cells from metastatic carcinoma of the prostate may stimulate osteoblastic activity and produce focal areas of localized increased density, i.e., sclerotic bone lesions. The lesions may also be diffuse. These lesions are most often seen in the vertebrae, ribs, pelvis, humeri, and femora (Fig. 21-7). The radionuclide bone scan is currently the study of choice for detecting skeletal metastases, regardless of the suspected primary (Box 21-3).

The radionuclide bone scan is currently the study of choice for detecting skeletal metastases, regardless of the suspected primary (Box 21-3).

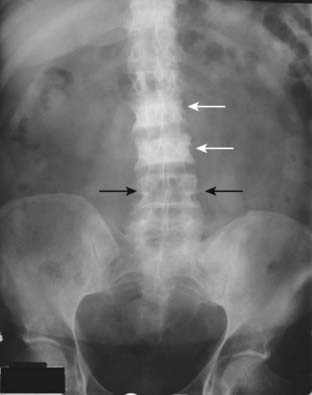

Figure 21-7 Focal increase in bone density from carcinoma of the breast.

A frontal view of the lumbar spine and pelvis demonstrates abnormally dense vertebral bodies most marked at L2 and L3 (solid white arrows). Notice how the pedicles are obscured by the abnormally increased density of the vertebral body compared to the normal pedicles at L4 (solid black arrows). Dense, white vertebrae are called ivory vertebrae. Osteoblastic metastases from carcinoma of the breast and prostate are two causes of an ivory vertebra.

Box 21-3 Finding Metastases to Bone—Bone Scan

Avascular Necrosis of Bone

Avascular necrosis (AVN) of bone (also called ischemic necrosis, aseptic necrosis, osteonecrosis) results from cellular death and leads to collapse of the affected bone. It usually involves those bones that have a relatively poor collateral blood supply (e.g., scaphoid in the wrist or the head of the femur) and tends to affect the hematopoietic elements of marrow earliest so that MRI is the most sensitive modality for detecting AVN.

Avascular necrosis (AVN) of bone (also called ischemic necrosis, aseptic necrosis, osteonecrosis) results from cellular death and leads to collapse of the affected bone. It usually involves those bones that have a relatively poor collateral blood supply (e.g., scaphoid in the wrist or the head of the femur) and tends to affect the hematopoietic elements of marrow earliest so that MRI is the most sensitive modality for detecting AVN. There are a myriad of causes of avascular necrosis. Some of the more common are shown in Table 21-2.

There are a myriad of causes of avascular necrosis. Some of the more common are shown in Table 21-2. On conventional radiographs, the region of avascular necrosis appears denser than the surrounding bone. On MRI, there is usually a decrease from the normal high signal produced by fatty marrow (Fig. 21-8).

On conventional radiographs, the region of avascular necrosis appears denser than the surrounding bone. On MRI, there is usually a decrease from the normal high signal produced by fatty marrow (Fig. 21-8). The devascularized bone becomes denser and therefore appears more sclerotic than the remainder of the bone. This especially occurs in the femoral head (Fig. 21-9) and humeral head (Fig. 21-10).

The devascularized bone becomes denser and therefore appears more sclerotic than the remainder of the bone. This especially occurs in the femoral head (Fig. 21-9) and humeral head (Fig. 21-10). On conventional radiographs, old medullary bone infarcts are recognized as dense, amorphous deposits of bone within the medullary cavities of long bones, frequently marginated by a thin, sclerotic membrane (Fig. 21-11).

On conventional radiographs, old medullary bone infarcts are recognized as dense, amorphous deposits of bone within the medullary cavities of long bones, frequently marginated by a thin, sclerotic membrane (Fig. 21-11).TABLE 21-2 SOME CAUSES OF AVASCULAR NECROSIS OF BONE

| Location | Example of Disease |

|---|---|

| Intravascular | Sickle-cell disease |

| Polycythemia vera | |

| Vascular | Vasculitis (lupus and radiation-induced) |

| Extravascular | Trauma (fractures) |

| Idiopathic | Exogenous steroids and Cushing disease |

| Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease |

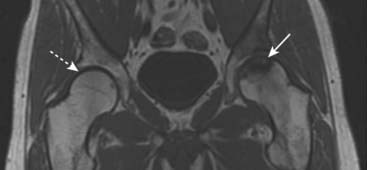

Figure 21-8 Avascular necrosis, MRI.

A T1-weighted coronal view of both hips demonstrates normal high signal from the fatty marrow in the right femur (dotted white arrow) but decreased signal in the left femoral head extending to the subchondral bone of the left hip joint (solid white arrow). The joint space is preserved.

Figure 21-9 Avascular necrosis of the left femoral head in a patient on long-term steroids for lupus erythematosus.

A close-up view of the left femoral head shows a zone of increased sclerosis in the superior aspect of the femoral head (solid white arrows), a characteristic finding of avascular necrosis of the head. The linear, subcortical lucency (solid black arrow) represents subchondral fractures seen with this disease, called the crescent sign. Notice that the disease is isolated to the femoral head and involves neither the joint space nor the acetabulum, i.e., this it is not an arthritis.

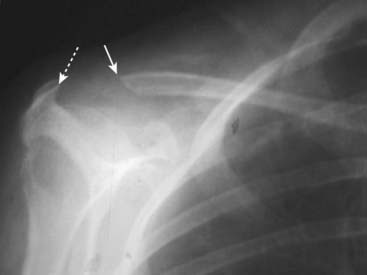

Figure 21-10 Avascular necrosis of humeral head.

There is increased density seen at the very top of the humeral head (solid black arrow) in this patient with sickle cell disease who developed avascular necrosis of the humeral head. Because the white cap on the bone looks like snow on a mountaintop, this sign of avascular necrosis has been called snow-capping.

Figure 21-11 Old medullary bone infarct.

Amorphous calcification is seen in the medullary cavity of the proximal femur (solid white arrows). In general, the differential diagnosis for such an intramedullary calcification includes bone infarct or enchondroma. The characteristic thin sclerotic membrane surrounding this lesion identifies it as a bone infarct.

Paget Disease

Paget disease is a chronic disease of bone, most often occurring in older men, now believed to be due to chronic paramyxoviral infection. It is characterized by varying degrees of increased bone resorption and increased bone formation with the latter predominating in those cases seen in more progressive forms of the disease.

Paget disease is a chronic disease of bone, most often occurring in older men, now believed to be due to chronic paramyxoviral infection. It is characterized by varying degrees of increased bone resorption and increased bone formation with the latter predominating in those cases seen in more progressive forms of the disease. The end result is almost always a denser bone that, despite its density, is mechanically inferior to normal bone and thus susceptible to pathologic fractures or bone-softening deformities such as bowing. The pelvis is most frequently involved, followed by the lumbar spine, thoracic spine, proximal femur, and calvarium.

The end result is almost always a denser bone that, despite its density, is mechanically inferior to normal bone and thus susceptible to pathologic fractures or bone-softening deformities such as bowing. The pelvis is most frequently involved, followed by the lumbar spine, thoracic spine, proximal femur, and calvarium.

![]() Paget disease is usually diagnosed using conventional radiography. The imaging hallmarks of Paget disease:

Paget disease is usually diagnosed using conventional radiography. The imaging hallmarks of Paget disease:

Thickening of the cortex. To recognize thickening of the cortex, compare the thickness of the cortex of the suspicious area with another part of the same bone or, if visible, the same bone on the opposite side of the body.

Thickening of the cortex. To recognize thickening of the cortex, compare the thickness of the cortex of the suspicious area with another part of the same bone or, if visible, the same bone on the opposite side of the body. Accentuation of the trabecular pattern. There is coarsening and thickening of the trabeculae (Fig. 21-12).

Accentuation of the trabecular pattern. There is coarsening and thickening of the trabeculae (Fig. 21-12). Increase in the size of the bone involved. The “classical” history for Paget disease, rendered less useful as fashions have changed, was a gradual increase in a man’s hat size as the calvarium increased in size from this disease.

Increase in the size of the bone involved. The “classical” history for Paget disease, rendered less useful as fashions have changed, was a gradual increase in a man’s hat size as the calvarium increased in size from this disease.

Figure 21-12 Paget disease of the pelvis, two patients.

A, A frontal view of the pelvis shows an increase in bony density in the left hemipelvis, accentuation and coarsening of the trabeculae, and thickening of the cortex (white circle), the hallmarks of Paget disease of bone. Compare the left hemipelvis with the normal right side. B, Axial CT scan of the pelvis of another patient with Paget disease demonstrates thickening of the cortex and accentuation of the trabeculae in the right ilium (solid white arrow). Compare it with the normal left side (dotted white arrow).

Recognizing a Generalized Decrease in Bone Density

The bones will have an overall increase in lucency. There may be a diffuse loss of the normal network of bony trabeculae in the medullary cavity because of the decrease in, and thinning of, many of the smaller trabecular structures.

The bones will have an overall increase in lucency. There may be a diffuse loss of the normal network of bony trabeculae in the medullary cavity because of the decrease in, and thinning of, many of the smaller trabecular structures. Accentuation of the normal corticomedullary junction may be present in which the cortex, although thinner than normal, stands out more strikingly because of the decreased density of the medullary cavity (Fig. 21-13).

Accentuation of the normal corticomedullary junction may be present in which the cortex, although thinner than normal, stands out more strikingly because of the decreased density of the medullary cavity (Fig. 21-13).

Figure 21-13 Normal and osteoporotic foot.

Normal frontal view of the foot (A) to contrast with (B), which shows overall decreased density of the bone and thinning of the cortices (solid white arrows) secondary to disuse osteoporosis. Conventional radiographs are insensitive in diagnosing osteoporosis, and they are subject to technical variations that can mimic the disease even in a healthy individual. More sensitive methods, such as a DEXA scan, should be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is defined as a systemic skeletal disorder characterized by low bone mineral density (BMD) and generally divided into postmenopausal and age-related bone loss.

Osteoporosis is defined as a systemic skeletal disorder characterized by low bone mineral density (BMD) and generally divided into postmenopausal and age-related bone loss.

Additional factors that increase the risk of osteoporosis include exogenous steroid administration, Cushing disease, estrogen deficiency, inadequate physical activity, and alcoholism.

Additional factors that increase the risk of osteoporosis include exogenous steroid administration, Cushing disease, estrogen deficiency, inadequate physical activity, and alcoholism. Osteoporosis predisposes to pathologic fractures in the femoral neck, can lead to compression fractures of the vertebral bodies, and fractures of the distal radius (Colles’ fractures).

Osteoporosis predisposes to pathologic fractures in the femoral neck, can lead to compression fractures of the vertebral bodies, and fractures of the distal radius (Colles’ fractures). Conventional radiographs are relatively insensitive for detecting osteoporosis. Almost 50% of bone mass must be lost before it is recognizable on conventional radiographs. Findings on conventional radiographs include overall lucency of bone, thinning of the cortex, and decrease in the visible number of trabeculae in the medullary cavity.

Conventional radiographs are relatively insensitive for detecting osteoporosis. Almost 50% of bone mass must be lost before it is recognizable on conventional radiographs. Findings on conventional radiographs include overall lucency of bone, thinning of the cortex, and decrease in the visible number of trabeculae in the medullary cavity. Currently, DEXA (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry) scans are the most accurate and widely recommended method for bone mineral density measurements.

Currently, DEXA (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry) scans are the most accurate and widely recommended method for bone mineral density measurements.

Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism is a condition caused by excessive secretion of parathormone (PTH) by the parathyroid glands. Parathormone exerts its effects on bones, the kidneys, and the GI tract. Its effect on bones is to increase resorption by stimulating osteoclastic activity. Calcium is removed from the bone and deposited in the bloodstream.

Hyperparathyroidism is a condition caused by excessive secretion of parathormone (PTH) by the parathyroid glands. Parathormone exerts its effects on bones, the kidneys, and the GI tract. Its effect on bones is to increase resorption by stimulating osteoclastic activity. Calcium is removed from the bone and deposited in the bloodstream. The diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism is based on clinical and laboratory findings but there are numerous findings of the disease on conventional radiographs and there are other imaging studies utilized to direct surgery on the glands, if indicated. Imaging studies of the parathyroid glands themselves may include ultrasound, nuclear medicine parathyroid scans, and MRI scans.

The diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism is based on clinical and laboratory findings but there are numerous findings of the disease on conventional radiographs and there are other imaging studies utilized to direct surgery on the glands, if indicated. Imaging studies of the parathyroid glands themselves may include ultrasound, nuclear medicine parathyroid scans, and MRI scans.

TABLE 21-3 FORMS OF HYPERPARATHYROIDISM

| Type | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Primary | Usually caused by a single adenoma in most patients (80% to 90%) and almost always results in hypercalcemia. |

| Secondary | Results from hyperplasia of the glands secondary to imbalances in calcium and phosphorous levels, seen mostly with chronic renal disease. |

| Tertiary | Occurs in patients with long-standing secondary hyperparathyroidism in whom autonomous hypersecretion of parathyroid hormone develops, leading to hypercalcemia. |

![]() Some of the findings of hyperparathyroidism on conventional radiographs:

Some of the findings of hyperparathyroidism on conventional radiographs:

Subperiosteal bone resorption, especially on the radial side of the middle phalanges of the index and middle fingers (Fig. 21-14)

Subperiosteal bone resorption, especially on the radial side of the middle phalanges of the index and middle fingers (Fig. 21-14) Well-circumscribed lytic lesions in the long bones called brown tumors and a salt-and-pepper appearance of the skull (Fig. 21-16)

Well-circumscribed lytic lesions in the long bones called brown tumors and a salt-and-pepper appearance of the skull (Fig. 21-16)

Figure 21-14 Subperiosteal resorption in hyperparathyroidism.

The radiologic hallmark of hyperparathyroidism is subperiosteal bone resorption, seen especially well on the radial aspect of the middle phalanges of the index and middle fingers (solid white arrows). Here the cortex appears shaggy and irregular, compared to the cortex on the opposite side of the same bone which is well defined. This patient also displays two other findings of hyperparathyroidism: a small brown tumor (solid black arrow) and resorption of the terminal phalanges (acroosteolysis) (dotted white arrows).

Figure 21-15 Erosion of distal clavicle in hyperparathyroidism.

Another relatively common site of bone resorption in hyperparathyroidism is the distal end of the clavicle. Here the distal clavicle (solid white arrow), which should articulate with the acromion (dotted white arrow), has been resorbed, increasing the distance between it and the acromion. Other sites of bone resorption might include the terminal phalanges as in Fig. 21-14, the lamina dura of the teeth and the medial aspect of the tibia, humerus, and femur.

There is a geographic, lytic lesion in the midshaft of the tibia (solid black arrows). Brown tumors (also called osteoclastomas) are benign lesions that represent the osteoclastic resorption of a localized area of (usually) cortical bone and its replacement with fibrous tissue and blood. Their high hemosiderin content gives them a characteristic brown color; they were not named after a “Dr. Brown.” The lesions can look like osteolytic metastases or multiple myeloma, so that the clinical history of hyperparathyroidism is key. They can be seen with both primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Rickets

Rickets is caused by a wide variety of disorders, mostly related to abnormalities in vitamin D ingestion, absorption, or activation, the end result of which is a failure to calcify the osteoid matrix of bone, especially at the sites of maximal growth in children.

Rickets is caused by a wide variety of disorders, mostly related to abnormalities in vitamin D ingestion, absorption, or activation, the end result of which is a failure to calcify the osteoid matrix of bone, especially at the sites of maximal growth in children. Rickets usually results either from a deficiency, or abnormal metabolism, of vitamin D or from abnormal metabolism or excretion of inorganic phosphate.

Rickets usually results either from a deficiency, or abnormal metabolism, of vitamin D or from abnormal metabolism or excretion of inorganic phosphate. By definition, rickets occurs only in children whose growth plates have not closed (which occurs at approximately 17 years of age in females and 19 years of age in males).

By definition, rickets occurs only in children whose growth plates have not closed (which occurs at approximately 17 years of age in females and 19 years of age in males).

Fraying and cupping at the metaphyses of long bones including the anterior ends of the ribs (rachitic rosary) (Fig. 21-17).

Fraying and cupping at the metaphyses of long bones including the anterior ends of the ribs (rachitic rosary) (Fig. 21-17).

Frontal view of the wrist shows cupping and fraying (solid black arrows) of the metaphyses of the distal radius and ulna, characteristic findings of rickets. Rickets will first affect the bones growing most quickly so it is most common around the knee, distal tibia, and distal radius. It may also be seen at the growing end of the ribs.

Osteomalacia

Osteomalacia is characterized by the failure to calcify the osteoid matrix of bone in adults, most commonly as the result of chronic renal disease.

Osteomalacia is characterized by the failure to calcify the osteoid matrix of bone in adults, most commonly as the result of chronic renal disease.

The imaging hallmark of osteomalacia is the pseudofracture (Looser line), which is a fracture that frequently occurs at multiple sites at the same time and is associated with nonunion due to inadequate calcification of the healing fracture.

The imaging hallmark of osteomalacia is the pseudofracture (Looser line), which is a fracture that frequently occurs at multiple sites at the same time and is associated with nonunion due to inadequate calcification of the healing fracture. Common locations for pseudofractures are the medial femoral neck and shaft, pubic and ischial rami, metatarsals, and calcaneus. They typically appear as short, lucent bands, at right angles to the cortex with sclerotic margins in later stages. They are frequently bilateral and symmetrical (Fig. 21-18).

Common locations for pseudofractures are the medial femoral neck and shaft, pubic and ischial rami, metatarsals, and calcaneus. They typically appear as short, lucent bands, at right angles to the cortex with sclerotic margins in later stages. They are frequently bilateral and symmetrical (Fig. 21-18).

Figure 21-18 Looser line (pseudofracture).

A close-up view of the femoral neck shows the typical features of a Looser line: short, lucent bands, at right angles to the cortex with sclerotic margins (solid black arrow). Looser lines are the hallmark of osteomalacia in adults. They are frequently bilateral and symmetrical.

Recognizing a Focal Decrease in Bone Density

Osteolytic Metastatic Disease

The medullary cavity is almost always involved and from there the disease may erode into and destroy the cortex as well. When the medullary cavity alone is involved, there must be almost a 50% reduction in bone mass in order for the lesion to be recognizable on conventional radiographs when viewed en face.

The medullary cavity is almost always involved and from there the disease may erode into and destroy the cortex as well. When the medullary cavity alone is involved, there must be almost a 50% reduction in bone mass in order for the lesion to be recognizable on conventional radiographs when viewed en face. MRI, on the other hand, is excellent at demonstrating the status of the medullary cavity and so is much more sensitive to the presence of metastatic disease than conventional radiography (Fig. 21-19).

MRI, on the other hand, is excellent at demonstrating the status of the medullary cavity and so is much more sensitive to the presence of metastatic disease than conventional radiography (Fig. 21-19). In some cases, only the cortex is involved. Cortical metastases may be easier to visualize on conventional radiographs because relatively less cortical destruction is needed for them to become apparent, especially if the lesions happen to be viewed in tangent.

In some cases, only the cortex is involved. Cortical metastases may be easier to visualize on conventional radiographs because relatively less cortical destruction is needed for them to become apparent, especially if the lesions happen to be viewed in tangent.

Box 21-6 Metastatic Disease to Bone

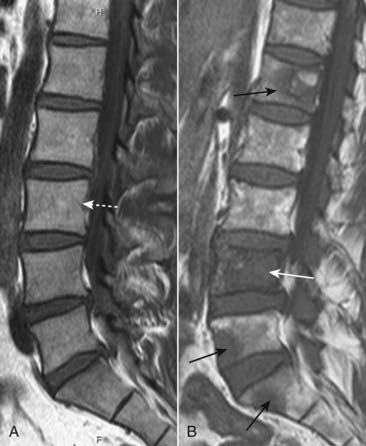

Figure 21-19 Metastases to lumbar spine, MRI.

A, There is normal signal in the lumbar vertebral bodies on this T1-weighted sagittal view of the lumbar spine (dotted white arrow). B, In this patient with a primary breast carcinoma, there are multiple metastatic deposits replacing the normal marrow in the lumbar spine and sacrum (solid black arrows). The body of L4 is completely replaced by tumor (solid white arrow).

![]() On conventional radiographs, the classical findings of osteolytic metastases include:

On conventional radiographs, the classical findings of osteolytic metastases include:

These lytic lesions are frequently characterized as belonging to one (or sometimes more) of three patterns: permeative, mottled, or geographic in order of increasing size of the smallest and most discrete lesion visible (Fig. 21-20).

These lytic lesions are frequently characterized as belonging to one (or sometimes more) of three patterns: permeative, mottled, or geographic in order of increasing size of the smallest and most discrete lesion visible (Fig. 21-20). Osteolytic metastases typically incite little or no reactive bone formation around them. They can be expansile and soap-bubbly (i.e., contain bony septations) especially in renal and thyroid carcinoma (Fig. 21-21).

Osteolytic metastases typically incite little or no reactive bone formation around them. They can be expansile and soap-bubbly (i.e., contain bony septations) especially in renal and thyroid carcinoma (Fig. 21-21). In the spine, they may preferentially destroy the pedicles, because of the blood supply to the pedicles (the pedicle sign), which can help to differentiate metastases from multiple myeloma (see below), which tends to spare the pedicle early in the disease (Fig. 21-22).

In the spine, they may preferentially destroy the pedicles, because of the blood supply to the pedicles (the pedicle sign), which can help to differentiate metastases from multiple myeloma (see below), which tends to spare the pedicle early in the disease (Fig. 21-22).

Figure 21-20 Three patterns of lytic bone lesions.

A, A solitary bone lesion with a gradual zone of transition between it and the normal bone and complete destruction of the cortex (solid white arrow) is called a geographic lesion. B, Several ill-defined lytic lesions (solid white arrows) with indistinct margins imply a more aggressive malignancy. This is called a moth-eaten pattern. C, A close-up of the femur shows innumerable, small, irregular holes in the bone (white circle) called a permeative pattern. Permeative lesions are called round cell lesions for the shape of the cells that produce them. Such lesions include Ewing sarcoma, neuroblastoma, myeloma, and leukemia.

Figure 21-21 Expansile renal cell carcinoma metastasis.

This is a very aggressive and expansile osteolytic metastasis in the humerus from a primary renal cell carcinoma. Notice that the cortex has been destroyed in several areas (dotted white arrows) and the lesion has a characteristic soap-bubbly appearance produced by fine septae (solid white arrow). Metastatic thyroid carcinoma and a solitary plasmacytoma could also produce these findings.

There is destruction of the right pedicle of T10 (dotted white arrow). Each vertebral body should normally have two, oval-shaped pedicles, one on each side, visible on the frontal radiograph of the spine (solid white arrows). In the spine, osteolytic metastases may preferentially destroy the pedicles, because of their blood supply, producing the pedicle sign, although most metastatic lesions to the spine will also involve the vertebral body as well. In multiple myeloma, the pedicle tends to be spared early in the disease.

TABLE 21-4 CAUSES OF OSTEOBLASTIC AND OSTEOLYTIC BONE METASTASES

| Osteoblastic | Osteolytic |

|---|---|

| Prostate carcinoma (most common in older males) | Lung cancer (most common osteolytic lesion in males) |

| Breast carcinoma is usually osteolytic but can be osteoblastic, especially if treated | Breast cancer (most common osteolytic lesion in females) |

| Lymphoma | Renal cell carcinoma |

| Carcinoid tumors | Thyroid carcinoma |

Multiple Myeloma

Multiple myeloma, the most common primary malignancy of bone in adults, can occur in a solitary form, often seen as a soap-bubbly, expansile lesion in the spine or pelvis (called a solitary plasmacytoma), or a disseminated form with multiple, punched-out lytic lesions throughout the axial and proximal appendicular skeleton.

Multiple myeloma, the most common primary malignancy of bone in adults, can occur in a solitary form, often seen as a soap-bubbly, expansile lesion in the spine or pelvis (called a solitary plasmacytoma), or a disseminated form with multiple, punched-out lytic lesions throughout the axial and proximal appendicular skeleton.

Plasmacytomas appear as expansile, septated lesions, frequently with associated soft tissue masses (Fig. 21-23).

Plasmacytomas appear as expansile, septated lesions, frequently with associated soft tissue masses (Fig. 21-23). Later, in its disseminated form, multiple, small, sharply circumscribed (described as punched out) lytic lesions of approximately the same size are present, usually without any accompanying sclerotic reaction around them (Fig. 21-24).

Later, in its disseminated form, multiple, small, sharply circumscribed (described as punched out) lytic lesions of approximately the same size are present, usually without any accompanying sclerotic reaction around them (Fig. 21-24). Classically, conventional radiographs are more sensitive in detecting the lesions of multiple myeloma than radionuclide bone scans, which tend to underestimate the number and extent of lesions due to the absence of reactive bone formation.

Classically, conventional radiographs are more sensitive in detecting the lesions of multiple myeloma than radionuclide bone scans, which tend to underestimate the number and extent of lesions due to the absence of reactive bone formation.

Figure 21-23 Solitary plasmacytoma, shoulder.

There is a lytic lesion in the proximal humerus (solid black arrow), which destroys the cortex (dotted black arrow) and contains multiple septations (solid white arrow). This is the so-called soap-bubbly appearance and can be seen with expansile metastases and solitary plasmacytomas, a precursor to the more disseminated form of multiple myeloma.

Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis refers to the focal destruction of bone most often by a blood-borne infectious agent, the most common of which is Staphylococcus aureus.

Osteomyelitis refers to the focal destruction of bone most often by a blood-borne infectious agent, the most common of which is Staphylococcus aureus. In children, the osteolytic lesion tends to occur at the metaphysis because of its rich blood supply.

In children, the osteolytic lesion tends to occur at the metaphysis because of its rich blood supply.

![]() Findings of acute osteomyelitis on conventional radiographs:

Findings of acute osteomyelitis on conventional radiographs:

Inflammatory changes accompanying the infection may produce soft tissue swelling and focal osteoporosis from hyperemia.

Inflammatory changes accompanying the infection may produce soft tissue swelling and focal osteoporosis from hyperemia. In adults, the infection tends to involve the joint space more often than in children producing not only osteomyelitis but also septic arthritis (see Chapter 24, Arthritis).

In adults, the infection tends to involve the joint space more often than in children producing not only osteomyelitis but also septic arthritis (see Chapter 24, Arthritis). Conventional radiographs can take up to 10 days to display the first findings of osteomyelitis so that other imaging modalities, such as MRI and nuclear medicine studies, are frequently used for earlier diagnosis.

Conventional radiographs can take up to 10 days to display the first findings of osteomyelitis so that other imaging modalities, such as MRI and nuclear medicine studies, are frequently used for earlier diagnosis. A variety of radionuclide bone scans can demonstrate osteomyelitis. The most specific is currently a tagged, white-cell scan in which a sample of the patient’s white blood cells is tagged with a radioactive isotope (frequently indium), before the patient is imaged with a camera specific for nuclear studies to detect a site of abnormally increased radioactive tracer uptake.

A variety of radionuclide bone scans can demonstrate osteomyelitis. The most specific is currently a tagged, white-cell scan in which a sample of the patient’s white blood cells is tagged with a radioactive isotope (frequently indium), before the patient is imaged with a camera specific for nuclear studies to detect a site of abnormally increased radioactive tracer uptake.Pathologic Fractures

Pathologic fractures are those that occur in bone with a preexisting abnormality. Pathologic fractures tend to occur with minimum or no trauma.

Pathologic fractures are those that occur in bone with a preexisting abnormality. Pathologic fractures tend to occur with minimum or no trauma. Diseases that produce either an increase or a decrease in bone density tend to weaken the normal architecture of bone and predispose to pathologic fractures.

Diseases that produce either an increase or a decrease in bone density tend to weaken the normal architecture of bone and predispose to pathologic fractures. Diseases that predispose to pathologic fractures may be local (e.g., metastases) or diffuse (e.g., rickets). In general, pathologic fractures occur more often in the ribs, spine, and proximal appendicular skeleton (humeri and femurs).

Diseases that predispose to pathologic fractures may be local (e.g., metastases) or diffuse (e.g., rickets). In general, pathologic fractures occur more often in the ribs, spine, and proximal appendicular skeleton (humeri and femurs). Attempts to predict impending fractures in diseased bone have, by and large, proven to be unreliable.

Attempts to predict impending fractures in diseased bone have, by and large, proven to be unreliable. The treatment of a pathologic fracture depends in part on successful treatment of the underlying condition that produced it, e.g., vitamin D replacement in rickets.

The treatment of a pathologic fracture depends in part on successful treatment of the underlying condition that produced it, e.g., vitamin D replacement in rickets.Box 21-7 Insufficiency Fractures

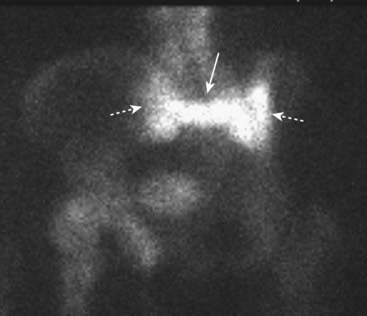

Figure 21-26 Sacral insufficiency fractures seen with bone scintigraphy.

There is increased radiotracer uptake in vertical fractures through the sacral ala (dotted white arrows) and a horizontal fracture through the body of the sacrum (solid white arrow). This has been called the Honda sign because it resembles the carmaker’s insignia. Insufficiency fractures occur in abnormal bones that undergo normal stress. The sacrum is a common site for such fractures in osteoporosis.

Figure 21-27 Pathologic fracture.

Pathologic fractures are those that occur with minimal stress in bones with preexisting abnormalities. In this patient with metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the humerus, there is a geographic, lytic lesion seen in the distal humerus (solid black arrows) through which a transverse fracture has occurred (solid white arrow).

Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Recognizing Abnormalities of Bone Density on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Recognizing Abnormalities of Bone Density

Bones consist of a cortex of compact bone surrounding a medullary cavity containing cancellous bone arranged as trabeculae, separated by blood vessels, hematopoietic cells, and fat.

On conventional radiographs, the cortex is best seen in tangent. On CT, the entire cortex is visualized. MRI is particularly sensitive to assessment of the marrow. Both CT and MRI are superior to conventional radiographs in evaluating soft tissues.

Bone is undergoing continuous change from a combination of biochemical and mechanical forces.

Increased osteoclastic activity can produce focal or generalized decrease in bone density. Increased osteoblastic activity can produce focal or diffuse increased bone density. Osteoblastic metastases, especially from carcinoma of the prostate and breast, can produce focal or generalized increase in bony density.

Other diseases that can increase bone density include osteopetrosis, avascular necrosis of bone, and Paget disease.

Hallmarks of Paget disease include thickening of the cortex, accentuation of the trabecular pattern, and enlargement and increased density of the affected bone.

Osteolytic metastases, especially from lung, renal, thyroid, and breast cancer, can produce focal areas of decreased bone density as can solitary plasmacytomas, considered to be a precursor to multiple myeloma, the most common primary tumor of bone.

Examples of diseases that can cause a generalized decrease in bone density include osteoporosis, hyperparathyroidism, rickets (in children), and osteomalacia (in adults).

Osteoporosis is characterized by low bone mineral density and is most often either postmenopausal or age-related. Osteoporosis predisposes to pathologic fractures.

Pathologic fractures are those that occur with minimal or no trauma in bones that had a preexisting abnormality.

Examples of diseases that can cause a focal decrease in bone density include metastases, multiple myeloma, and osteomyelitis.

The radionuclide bone scan is the modality of choice in screening for skeletal metastases. MRI is used primarily to solve specific questions related to a lesion’s composition and extent.

There must be almost a 50% reduction in the mass of bone in order for a difference in density to be perceived on conventional radiographs; MRI is much more sensitive to the presence of medullary metastatic disease.