Chapter 24 Recognizing Some Common Causes of Neck and Back Pain

Conventional Radiography, MRI, and CT

Conventional radiographs remain an important method of evaluating certain spinal lesions because they are inexpensive and rapidly available, even on a portable basis if needed, and they demonstrate bony anatomy well. They are utilized as a screening method for most spinal trauma.

Conventional radiographs remain an important method of evaluating certain spinal lesions because they are inexpensive and rapidly available, even on a portable basis if needed, and they demonstrate bony anatomy well. They are utilized as a screening method for most spinal trauma. Nevertheless, they provide little if any information about the important soft tissues of the spine and they use ionizing radiation to produce an image.

Nevertheless, they provide little if any information about the important soft tissues of the spine and they use ionizing radiation to produce an image.

![]() MRI, with its superior soft tissue differentiation, is the study of choice for most diseases of the spine because of its ability to visualize, and detect abnormalities in, soft tissues such as bone marrow, the spinal cord, and the intervertebral disks, its ability to display images in any plane, and the lack of exposure to radiation.

MRI, with its superior soft tissue differentiation, is the study of choice for most diseases of the spine because of its ability to visualize, and detect abnormalities in, soft tissues such as bone marrow, the spinal cord, and the intervertebral disks, its ability to display images in any plane, and the lack of exposure to radiation.

But MRI has its limitations. The study remains relatively expensive and its availability is not as widespread as CT or conventional radiographs, patients with pacemakers and certain internal ferromagnetic materials (aneurysm clips) are not able to be scanned, the procedure takes more time to complete, and some patients cannot tolerate the claustrophobia they experience in some of the high-field strength MRI scanners (see Chapter 20).

But MRI has its limitations. The study remains relatively expensive and its availability is not as widespread as CT or conventional radiographs, patients with pacemakers and certain internal ferromagnetic materials (aneurysm clips) are not able to be scanned, the procedure takes more time to complete, and some patients cannot tolerate the claustrophobia they experience in some of the high-field strength MRI scanners (see Chapter 20). CT, with its ability to reformat images in different planes and provide additional information about the soft tissues, now supplements and, in some cases, has replaced conventional radiography in the evaluation of spinal trauma. CT is utilized to determine the extent of the injury in any patient in whom a traumatic spinal injury has already been demonstrated by conventional radiographs.

CT, with its ability to reformat images in different planes and provide additional information about the soft tissues, now supplements and, in some cases, has replaced conventional radiography in the evaluation of spinal trauma. CT is utilized to determine the extent of the injury in any patient in whom a traumatic spinal injury has already been demonstrated by conventional radiographs.The Normal Spine

There are normally 7 cervical vertebrae, 12 thoracic vertebrae—all of which normally bear ribs—5 lumbar vertebrae, and 5 fused sacral vertebrae.

There are normally 7 cervical vertebrae, 12 thoracic vertebrae—all of which normally bear ribs—5 lumbar vertebrae, and 5 fused sacral vertebrae.Vertebral Body

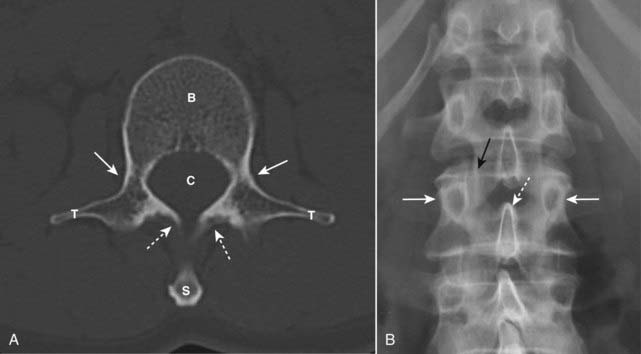

Each vertebra (well, almost every vertebra) has a body composed of inner cancellous bone and marrow and posterior elements made of compact, dense bone consisting of the pedicles, laminae, facets, transverse processes, and a spinous process (Fig. 24-1A).

Each vertebra (well, almost every vertebra) has a body composed of inner cancellous bone and marrow and posterior elements made of compact, dense bone consisting of the pedicles, laminae, facets, transverse processes, and a spinous process (Fig. 24-1A). From the level of C3 through the level of L5 the vertebral bodies are more or less rectangular in shape and of about equal height posteriorly as anteriorly.

From the level of C3 through the level of L5 the vertebral bodies are more or less rectangular in shape and of about equal height posteriorly as anteriorly. The articular facets of the superior and inferior articular processes are lined with cartilage, and these facet joints are true synovial joints.

The articular facets of the superior and inferior articular processes are lined with cartilage, and these facet joints are true synovial joints. In the frontal projection, each vertebral body displays two ovoid pedicles visible on each side of the vertebral body. The pedicles of L5 are frequently difficult to visualize, even in normal individuals due to the lordosis of the lumbar spine (Fig. 24-1B).

In the frontal projection, each vertebral body displays two ovoid pedicles visible on each side of the vertebral body. The pedicles of L5 are frequently difficult to visualize, even in normal individuals due to the lordosis of the lumbar spine (Fig. 24-1B).

Figure 24-1 Normal spine, axial CT (A), and frontal conventional radiograph (B).

A, In this CT scan of a “typical” vertebral body, we see the body (B), pedicles (solid white arrows), laminae (dotted white arrows), transverse processes (T), spinal canal (C), and spinous process (S). B, Each vertebral body has two pedicles that project as small ovals on either side of the vertebral body (solid white arrows). The spinous process (dotted white arrow) may be visualized slightly below the body to which it is attached. The facet joint is seen here en face (solid black arrow).

![]() In the cervical spine, three parallel arcuate lines should smoothly join (1) all of the spinolaminar white lines (the junction between the lamina and the spinous process), (2) the posterior aspects of the vertebral bodies, and (3) all of the anterior aspects of the vertebral bodies. Alterations in the smooth curvature of these three lines may indicate forward or backward displacement of all or part of the vertebral body (Fig. 24-2).

In the cervical spine, three parallel arcuate lines should smoothly join (1) all of the spinolaminar white lines (the junction between the lamina and the spinous process), (2) the posterior aspects of the vertebral bodies, and (3) all of the anterior aspects of the vertebral bodies. Alterations in the smooth curvature of these three lines may indicate forward or backward displacement of all or part of the vertebral body (Fig. 24-2).

On conventional radiographs of the lumbar spine performed in the oblique projection, the anatomic structures normally superimpose to produce a shadow that resembles the front end of a Scottish terrier, the famous Scottie dog sign (Fig. 24-3).

On conventional radiographs of the lumbar spine performed in the oblique projection, the anatomic structures normally superimpose to produce a shadow that resembles the front end of a Scottish terrier, the famous Scottie dog sign (Fig. 24-3).

Figure 24-2 The three cervical lines.

The lateral view of the cervical spine enables a quick assessment for spinal fracture/subluxation before further studies are performed that might involve motion of the patient’s neck. Three parallel arcuate lines should smoothly join all of the spinolaminar white lines, which are the junctions between the laminae and the spinous processes (dotted black line), a second line should join all of the posterior aspects of the vertebral bodies (solid black line), and a third should join all of the anterior aspects of the vertebral bodies (dotted white line).

Figure 24-3 Normal Scottie dog.

This is a left posterior oblique view of the lumbar spine (the patient is turned about halfway toward her own left). The “Scottie dog” is made up of the following: the “ear” (solid black arrow) is the superior articular facet, the “leg” (solid white arrow) is the inferior articular facet, the “nose” (dotted black arrow) is the transverse process, the “eye” (P) is the pedicle and the “neck” (dotted white arrow) is the pars interarticularis. All of these structures are paired—an identical set should be visible on the patient’s right side.

Intervertebral Disks

The intervertebral disks have a central gelatinous nucleus pulposus surrounded by an outer annulus fibrosus that is, in turn, made up of inner fibrocartilaginous fibers and outer cartilaginous fibers (Sharpey fibers). The nucleus pulposus is located near the posterior aspect of the disk.

The intervertebral disks have a central gelatinous nucleus pulposus surrounded by an outer annulus fibrosus that is, in turn, made up of inner fibrocartilaginous fibers and outer cartilaginous fibers (Sharpey fibers). The nucleus pulposus is located near the posterior aspect of the disk.

![]() The relative height of the disk space varies in each part of the spine.

The relative height of the disk space varies in each part of the spine.

Spinal Cord and Spinal Nerves

Spinal Ligaments

TABLE 24-1 LIGAMENTS OF THE SPINE

| Ligament | Connects |

|---|---|

| Anterior longitudinal ligament | Anterior surfaces of vertebral bodies |

| Posterior longitudinal ligament | Posterior surfaces of vertebral bodies |

| Ligamentum flavum | Laminae of adjacent vertebral bodies and lies in posterior portion of spinal canal |

| Interspinous ligament | Between spinous processes |

| Supraspinous ligament | Tips of spinous processes |

Normal MRI Appearance of the Spine

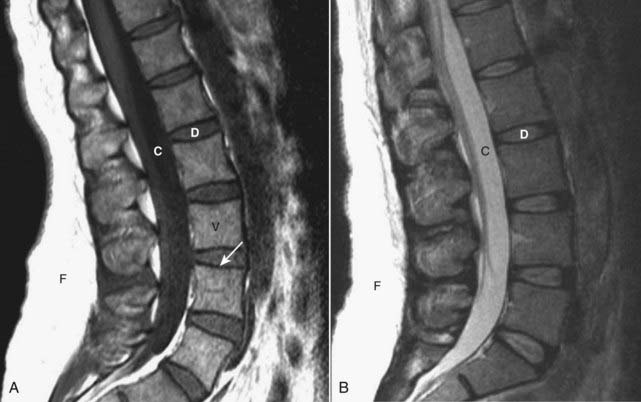

![]() On T1-weighted sagittal MRI images of the spine, the vertebral bodies, containing bone marrow, will normally be of high signal intensity (bright), the disks will be lower in signal intensity, and CSF in the thecal sac will have a low signal intensity (dark) (Fig. 24-4A).

On T1-weighted sagittal MRI images of the spine, the vertebral bodies, containing bone marrow, will normally be of high signal intensity (bright), the disks will be lower in signal intensity, and CSF in the thecal sac will have a low signal intensity (dark) (Fig. 24-4A).

Figure 24-4 Normal MRI lumbar spine, T1-weighted and T2-weighted images.

A, Sagittal T1-weighted image demonstrates the normal dark appearance of the disks (D) relative to the vertebral body (V). The CSF in the spinal canal is dark (C), and the subcutaneous fat of the back is bright (F). Cortical bone has a low signal (solid white arrow). B, Sagittal T2-weighted image demonstrates the normal appearance of the disks (D), which are slightly higher intensity (brighter) than the vertebral bodies. The CSF (C) in the spinal canal is now bright, and the subcutaneous fat (F) of the back remains bright.

On conventional T2-weighted images, the vertebral body will be slightly lower in signal intensity than the disks, while the CSF will appear bright (the reverse of T1) (Fig. 24-4B).

On conventional T2-weighted images, the vertebral body will be slightly lower in signal intensity than the disks, while the CSF will appear bright (the reverse of T1) (Fig. 24-4B).Back Pain

It has been estimated that almost 80% of all Americans will have some episode of back pain during their lifetime. The causes of back pain are numerous and the anatomic and physiologic interrelationships that produce it in many cases are still not known.

It has been estimated that almost 80% of all Americans will have some episode of back pain during their lifetime. The causes of back pain are numerous and the anatomic and physiologic interrelationships that produce it in many cases are still not known.Herniated Disks

Only about 2% of patients with acute low back pain have a herniated disk. In the lumbar region, disk herniation may lead to back pain and sciatica, while herniation of a cervical disk may produce radiculopathy and myelopathy. MRI is the study of choice for evaluating herniated disks.

Only about 2% of patients with acute low back pain have a herniated disk. In the lumbar region, disk herniation may lead to back pain and sciatica, while herniation of a cervical disk may produce radiculopathy and myelopathy. MRI is the study of choice for evaluating herniated disks. In the cervical spine, disk herniations occur most frequently at C4-C5, C5-C6, and C6-C7 (Fig. 24-5).

In the cervical spine, disk herniations occur most frequently at C4-C5, C5-C6, and C6-C7 (Fig. 24-5). Compared with the cervical and lumbar spine, thoracic disks are very stable, in part because they are protected by the rib cage that surrounds them.

Compared with the cervical and lumbar spine, thoracic disks are very stable, in part because they are protected by the rib cage that surrounds them.

Figure 24-5 Herniated disk, C4-C5 on MRI.

The spinal cord is dark (dotted white arrow) relative to the high intensity (whiter) signal surrounding it which is the cerebrospinal fluid in the spinal canal. A herniated disk (solid white arrow) extends posteriorly from the C4-C5 disk space and compresses the cord.

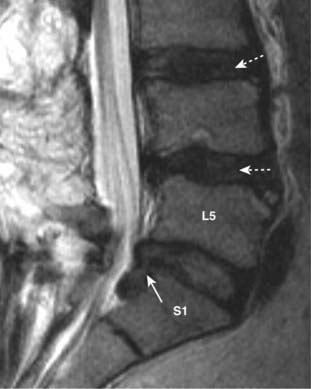

![]() The majority of disk herniations occur at the lower three lumbar disk levels, L3-L4, L4-L5 (most common), and L5-S1. More than 60% of disk herniations occur posterolaterally, the location of the herniation determining the clinical presentation depending on which nerve roots are compressed.

The majority of disk herniations occur at the lower three lumbar disk levels, L3-L4, L4-L5 (most common), and L5-S1. More than 60% of disk herniations occur posterolaterally, the location of the herniation determining the clinical presentation depending on which nerve roots are compressed.

Degeneration of the outer annular fibers of the disk or trauma can lead to an interruption in those fibers and allow the disk material to bulge, which may or may not be associated with back pain.

Degeneration of the outer annular fibers of the disk or trauma can lead to an interruption in those fibers and allow the disk material to bulge, which may or may not be associated with back pain. When the annular fibers rupture, the nucleus pulposus may herniate (usually posterolaterally) through a weakened area of the posterior longitudinal ligament.

When the annular fibers rupture, the nucleus pulposus may herniate (usually posterolaterally) through a weakened area of the posterior longitudinal ligament. The herniated material may protrude but remain in contact with the parent disk from which it originated or it may be completely extruded into the spinal canal.

The herniated material may protrude but remain in contact with the parent disk from which it originated or it may be completely extruded into the spinal canal. Disk herniations can be visualized on both CT and MRI. CT demonstrates disk material compressing nerve roots or the thecal sac. On MRI, the herniated disk material is usually a focal, asymmetric protrusion of hypointense disk material that extends beyond the confines of the annulus fibrosus (Fig. 24-6).

Disk herniations can be visualized on both CT and MRI. CT demonstrates disk material compressing nerve roots or the thecal sac. On MRI, the herniated disk material is usually a focal, asymmetric protrusion of hypointense disk material that extends beyond the confines of the annulus fibrosus (Fig. 24-6). Postlaminectomy syndrome (also called failed back surgery syndrome) is persistent pain in the back or legs following spine surgery. In some studies, it has been estimated to occur in 40% of postoperative patients. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI studies of the spine are useful in differentiating persistent or recurrent disk herniation from scar formation as a cause of the pain.

Postlaminectomy syndrome (also called failed back surgery syndrome) is persistent pain in the back or legs following spine surgery. In some studies, it has been estimated to occur in 40% of postoperative patients. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI studies of the spine are useful in differentiating persistent or recurrent disk herniation from scar formation as a cause of the pain.

Figure 24-6 Disk herniation, L5-S1.

Sagittal T2-weighted image of the lower lumbar spine demonstrates disk material (solid white arrow) beyond the confines of the L5-S1 intervertebral disk space representing a disk herniation extending inferiorly. Notice that degeneration and desiccation of the other disks has led them to become darker than normal on this T2-weighted image (dotted white arrows).

Degenerative Disk Disease

With increasing age, the normally gelatinous nucleus pulposus becomes dehydrated and degenerates. This gradually leads to progressive loss of the height of the intervertebral disk space. At times, desiccation of the disk leads to release of nitrogen from tissues surrounding the disk resulting in the appearance of air density in the disk space called a vacuum-disk phenomenon. A vacuum-disk represents a late sign of a degenerated disk (Fig. 24-7).

With increasing age, the normally gelatinous nucleus pulposus becomes dehydrated and degenerates. This gradually leads to progressive loss of the height of the intervertebral disk space. At times, desiccation of the disk leads to release of nitrogen from tissues surrounding the disk resulting in the appearance of air density in the disk space called a vacuum-disk phenomenon. A vacuum-disk represents a late sign of a degenerated disk (Fig. 24-7). Degenerative disk disease (DDD) on MRI: The decrease in water content of the nucleus pulposus results in a lower signal intensity of the disk on T2-weighted images (see Fig. 24-6).

Degenerative disk disease (DDD) on MRI: The decrease in water content of the nucleus pulposus results in a lower signal intensity of the disk on T2-weighted images (see Fig. 24-6). Degenerative disk disease on conventional radiographs:

Degenerative disk disease on conventional radiographs:

It should be noted that osteophytes are an extremely common finding, increasing in prevalence with increasing age, and that most patients with osteophytes of the spine are asymptomatic.

It should be noted that osteophytes are an extremely common finding, increasing in prevalence with increasing age, and that most patients with osteophytes of the spine are asymptomatic.

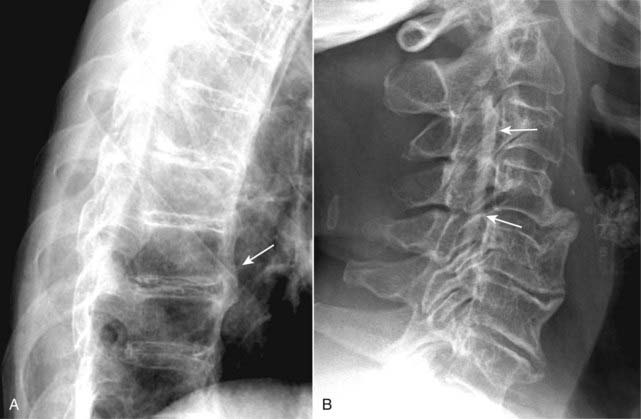

Figure 24-7 Degenerative disk disease.

With increasing age, there is progressive loss of the height of the intervertebral disk space. The endplates of contiguous vertebral bodies become sclerotic (solid black arrow), small osteophytes are produced at the margins of the vertebral bodies (solid white arrow), and there is desiccation of the disk with a vacuum-disk phenomenon (gas in the disk space) recognized by the air density in place of the disk seen at L5-S1 (dotted black arrow).

Osteoarthritis of the Facet Joints

The facet joints (also known as the apophyseal joints) are true joints in that they have cartilage, a synovial lining, and synovial fluid. As such, they are subject to developing osteoarthritis, similar to true joints in the appendicular skeleton.

The facet joints (also known as the apophyseal joints) are true joints in that they have cartilage, a synovial lining, and synovial fluid. As such, they are subject to developing osteoarthritis, similar to true joints in the appendicular skeleton. Some consider the small jointlike structures at the lateral edges of C3 to T1, called the uncovertebral joints or the joints of Luschka, to be true joints, but others do not.

Some consider the small jointlike structures at the lateral edges of C3 to T1, called the uncovertebral joints or the joints of Luschka, to be true joints, but others do not.

![]() In the cervical spine, osteophytes that develop at the uncovertebral joints can produce protrusions of bone into the normally oval-shaped neural foramina, which are visualized on conventional radiographs taken in the oblique projection (Fig. 24-8A).

In the cervical spine, osteophytes that develop at the uncovertebral joints can produce protrusions of bone into the normally oval-shaped neural foramina, which are visualized on conventional radiographs taken in the oblique projection (Fig. 24-8A).

There is usually a complex interrelationship between degenerative disk disease and facet arthritis such that the two frequently occur together. The osteophytes formed by osteoarthritis of the facet joints may also encroach on the neural foramina and produce radicular pain.

There is usually a complex interrelationship between degenerative disk disease and facet arthritis such that the two frequently occur together. The osteophytes formed by osteoarthritis of the facet joints may also encroach on the neural foramina and produce radicular pain. In the lumbar spine, facet osteoarthritis may cause narrowing and sclerosis of the facet joints, best seen on oblique views of the spine. Facet arthritis is easier to visualize on CT scans of the spine than on conventional radiographs, and actual nerve compression is easier to visualize on MRI of the spine (Fig. 24-8B).

In the lumbar spine, facet osteoarthritis may cause narrowing and sclerosis of the facet joints, best seen on oblique views of the spine. Facet arthritis is easier to visualize on CT scans of the spine than on conventional radiographs, and actual nerve compression is easier to visualize on MRI of the spine (Fig. 24-8B).

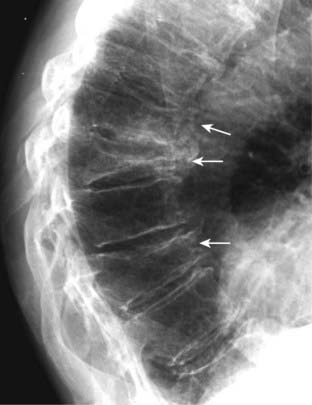

Figure 24-8 Uncovertebral osteophytes and facet arthritis.

A, In the cervical spine, osteophytes may develop at the uncovertebral joints (solid black arrow) producing bony protrusions into the normally oval-shaped neural foramina (N), in this radiograph taken in the oblique projection. Osteophytes at the uncovertebral joints are frequently associated with both degenerative disk disease (dotted white arrow) and osteophytes of the facet joints (solid white arrow). B, There is sclerosis and osteophyte formation involving the lower facet joints of the lumbar spine (solid black arrows) representing facet arthritis.

Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) is a common disorder characterized by bone or calcium formation at the sites of ligamentous insertions (enthesopathy).

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) is a common disorder characterized by bone or calcium formation at the sites of ligamentous insertions (enthesopathy). It usually affects men over the age of 50, can occur anywhere in the spine, but most often affects the lower thoracic and lower cervical spine.

It usually affects men over the age of 50, can occur anywhere in the spine, but most often affects the lower thoracic and lower cervical spine. Frequently patients with DISH complain of back stiffness but may have no pain or only mild back pain.

Frequently patients with DISH complain of back stiffness but may have no pain or only mild back pain. Conventional radiographs of the spine are sufficient to make the diagnosis of DISH.

Conventional radiographs of the spine are sufficient to make the diagnosis of DISH.

![]() DISH is manifest by thick, bridging, or flowing calcification/ossification of the anterior or sometimes posterior longitudinal ligaments.

DISH is manifest by thick, bridging, or flowing calcification/ossification of the anterior or sometimes posterior longitudinal ligaments.

This ossification is visualized along the anterior or anterolateral aspects of at least four contiguous vertebral bodies. Unlike degenerative disk disease, the disk spaces and usually the facet joints are preserved. The flowing ossification seen in DISH is separated slightly from the vertebral body (Fig. 24-9A).

This ossification is visualized along the anterior or anterolateral aspects of at least four contiguous vertebral bodies. Unlike degenerative disk disease, the disk spaces and usually the facet joints are preserved. The flowing ossification seen in DISH is separated slightly from the vertebral body (Fig. 24-9A).

Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) is often present with DISH and better visualized on CT and MRI than on conventional radiographs. It may cause compression of the spinal cord, especially in the cervical spine, due to narrowing of the spinal canal (see Fig. 24-9B).

Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) is often present with DISH and better visualized on CT and MRI than on conventional radiographs. It may cause compression of the spinal cord, especially in the cervical spine, due to narrowing of the spinal canal (see Fig. 24-9B).

Figure 24-9 Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL).

A, DISH is manifest by thick, bridging or flowing calcification/ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament (solid white arrow). This ossification is visualized along the anterior or anterolateral aspects of at least four contiguous vertebral bodies. B, OPLL, here shown by a long linear ossific density inside the spinal canal (solid white arrows), can be associated with DISH and may contribute to the production of spinal stenosis.

Compression Fractures of the Spine

Vertebral compression fractures are common, affecting women more than men, and typically secondary to osteoporosis. They may be asymptomatic or they may produce pain in the midthoracic or upper lumbar area that typically disappears in 4 to 6 weeks. Sometimes they are first noticed because of increasing kyphosis or loss of overall body height.

Vertebral compression fractures are common, affecting women more than men, and typically secondary to osteoporosis. They may be asymptomatic or they may produce pain in the midthoracic or upper lumbar area that typically disappears in 4 to 6 weeks. Sometimes they are first noticed because of increasing kyphosis or loss of overall body height. Conventional spine radiographs are usually the study of first choice. MRI can be utilized for differentiating osteoporotic compression fractures from malignancy. Both MRI and nuclear bone scans can help in establishing the age of a compression abnormality that might be impossible on conventional radiographs alone.

Conventional spine radiographs are usually the study of first choice. MRI can be utilized for differentiating osteoporotic compression fractures from malignancy. Both MRI and nuclear bone scans can help in establishing the age of a compression abnormality that might be impossible on conventional radiographs alone.

![]() Osteoporotic compression fractures usually involve the anterior and superior aspects of the vertebral body sparing the posterior body. There will usually be a difference in the height between the anterior and posterior aspects of the same vertebral body in excess of 3 mm. Alternatively, the compressed body is typically >20% shorter than the body above or below it.

Osteoporotic compression fractures usually involve the anterior and superior aspects of the vertebral body sparing the posterior body. There will usually be a difference in the height between the anterior and posterior aspects of the same vertebral body in excess of 3 mm. Alternatively, the compressed body is typically >20% shorter than the body above or below it.

This compression pattern produces a wedge-shaped deformity that leads to accentuation of the normal kyphosis in the thoracic spine (the so-called dowager’s hump) (Fig. 24-10).

This compression pattern produces a wedge-shaped deformity that leads to accentuation of the normal kyphosis in the thoracic spine (the so-called dowager’s hump) (Fig. 24-10). There is usually no neurologic deficit associated with an osteoporotic compression fracture because the fracture involves the anterior part of the vertebral body, away from the spinal cord.

There is usually no neurologic deficit associated with an osteoporotic compression fracture because the fracture involves the anterior part of the vertebral body, away from the spinal cord.

Figure 24-10 Compression fractures secondary to osteoporosis.

Vertebral compression fractures are common, affecting women more than men, and typically secondary to osteoporosis. Osteoporotic compression fractures usually involve the anterior and superior aspects of the vertebral body sparing the posterior aspect (solid white arrows). This produces a wedge-shaped deformity that leads to accentuation of the kyphosis in the thoracic spine. Progressive loss of overall body height is a common finding with compression fractures in the elderly.

Spondylolisthesis and Spondylolysis

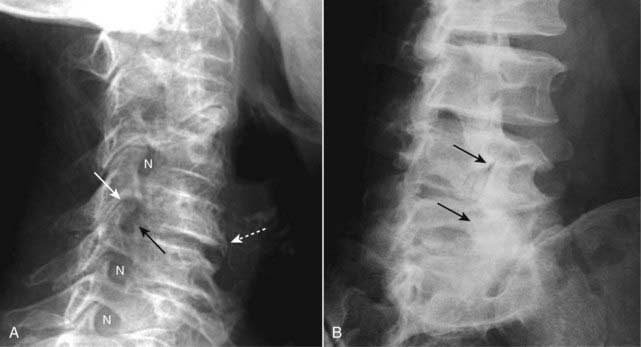

Spondylolisthesis is defined as slippage (typically forward) of one vertebral body (with the spine above it) on another. Forward slipping spondylolisthesis is also called anterolisthesis. Posterior slippage is called retrolisthesis. Spondylolisthesis is graded according to the degree one body has slipped on the adjacent body.

Spondylolisthesis is defined as slippage (typically forward) of one vertebral body (with the spine above it) on another. Forward slipping spondylolisthesis is also called anterolisthesis. Posterior slippage is called retrolisthesis. Spondylolisthesis is graded according to the degree one body has slipped on the adjacent body.

![]() In general, spondylolisthesis can occur if there are bilateral breaks in the pars interarticularis (spondylolytic spondylolisthesis) or if there is osteoarthritis of the facet joints (degenerative spondylolisthesis) (Fig. 24-11).

In general, spondylolisthesis can occur if there are bilateral breaks in the pars interarticularis (spondylolytic spondylolisthesis) or if there is osteoarthritis of the facet joints (degenerative spondylolisthesis) (Fig. 24-11).

Conventional radiographs of the lumbar spine are usually the initial imaging study. CT may be more helpful in detecting spondylolysis whereas MRI may demonstrate soft tissue abnormalities but be less effective in detecting spondylolysis.

Conventional radiographs of the lumbar spine are usually the initial imaging study. CT may be more helpful in detecting spondylolysis whereas MRI may demonstrate soft tissue abnormalities but be less effective in detecting spondylolysis. Spondylolysis is believed to be due to a combination of a congenitally dysplastic pars that is then subjected to the strains of an upright posture which eventually leads to a stress fracture of the pars. A family history of spondylolysis is relatively common.

Spondylolysis is believed to be due to a combination of a congenitally dysplastic pars that is then subjected to the strains of an upright posture which eventually leads to a stress fracture of the pars. A family history of spondylolysis is relatively common. Facet osteoarthritis may be associated with spondylolisthesis (degenerative spondylolisthesis) through a complex interaction between the ligaments, disks, and facet joints wherein disease in any one (or more) of these components increases the stress on the others which can lead to spondylolisthesis.

Facet osteoarthritis may be associated with spondylolisthesis (degenerative spondylolisthesis) through a complex interaction between the ligaments, disks, and facet joints wherein disease in any one (or more) of these components increases the stress on the others which can lead to spondylolisthesis. In degenerative spondylolisthesis, there is no break in the pars interarticularis. The degree of spondylolisthesis is usually less from this etiology than in those with spondylolisthesis from spondylolysis. Degenerative spondylolisthesis is more common in women and usually affects the L4-L5 disk space.

In degenerative spondylolisthesis, there is no break in the pars interarticularis. The degree of spondylolisthesis is usually less from this etiology than in those with spondylolisthesis from spondylolysis. Degenerative spondylolisthesis is more common in women and usually affects the L4-L5 disk space.

Recognizing spondylolisthesis/spondylolysis

Recognizing spondylolisthesis/spondylolysis

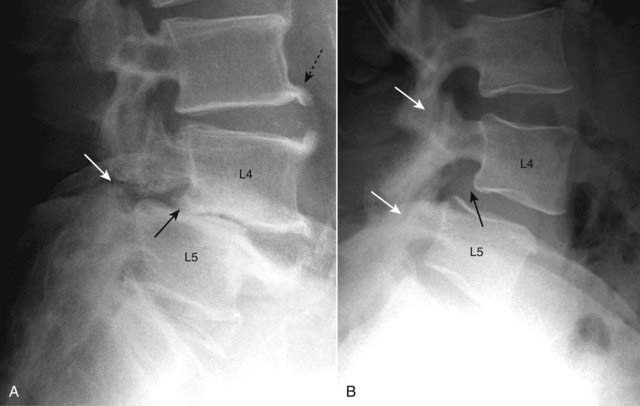

Figure 24-11 Spondylolytic spondylolisthesis (A) and degenerative spondylolisthesis (B).

A, There is forward slippage of L4 on L5 equal to about half the AP diameter of L5 (solid black arrow), so this is classified as a Grade II spondylolisthesis. Spondylolysis is present (solid white arrow) that has allowed the slip to take place. There are also incidental large osteophytes at the corners of the vertebral bodies (dotted black arrow). B, Facet osteoarthritis (solid white arrows) may be associated with spondylolisthesis through a complex interaction between the ligaments, disks, and facet joints. In degenerative spondylolisthesis, there is no break in the pars interarticularis and the degree of spondylolisthesis (solid black arrow) is usually less in this group than in those with spondylolisthesis from bilateral spondylolysis. The L4-L5 disk space is most commonly affected.

Spondylolysis is believed to be due to a combination of factors including a congenitally dysplastic pars that is subjected to certain strains that eventually lead to a stress fracture of the pars (solid black arrow). You might recognize the break as a “collar” on the “neck” of the Scottie dog (see Fig. 24-3). A normal pars is shown in the black circle. Spondylolysis allows the affected vertebral body to slip forward on the body below it (spondylolisthesis).

Spinal Stenosis

Spinal stenosis refers to narrowing of the spinal canal or the neural foramina secondary to soft tissue or bony abnormalities, either on an acquired or a congenital basis. Acquired etiologies such as those from degenerative changes are more common than congenital causes.

Spinal stenosis refers to narrowing of the spinal canal or the neural foramina secondary to soft tissue or bony abnormalities, either on an acquired or a congenital basis. Acquired etiologies such as those from degenerative changes are more common than congenital causes. Soft tissue abnormalities that can lead to spinal stenosis include hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum, bulging disk(s) and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL).

Soft tissue abnormalities that can lead to spinal stenosis include hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum, bulging disk(s) and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL). Bony abnormalities that can lead to spinal stenosis include a congenitally narrow spinal canal, osteophytes, facet osteoarthritis, or spondylolisthesis. A spinal canal that was borderline normal in size may become stenotic when any of these processes superimposes to further narrow the canal.

Bony abnormalities that can lead to spinal stenosis include a congenitally narrow spinal canal, osteophytes, facet osteoarthritis, or spondylolisthesis. A spinal canal that was borderline normal in size may become stenotic when any of these processes superimposes to further narrow the canal.

![]() Spinal stenosis is most common in the cervical and lumbar areas and can lead to radicular pain, myelopathy, or, in the lumbar region, neurogenic claudication. Neurogenic claudication is intermittent pain and paresthesias radiating down the leg worsened by standing or walking and relieved by flexing the spine by lying supine or squatting.

Spinal stenosis is most common in the cervical and lumbar areas and can lead to radicular pain, myelopathy, or, in the lumbar region, neurogenic claudication. Neurogenic claudication is intermittent pain and paresthesias radiating down the leg worsened by standing or walking and relieved by flexing the spine by lying supine or squatting.

Conventional radiographs are usually obtained first in evaluating for spinal stenosis, but MRI is the study of choice because the bony dimensions alone do not account for the soft tissues that can produce stenosis.

Conventional radiographs are usually obtained first in evaluating for spinal stenosis, but MRI is the study of choice because the bony dimensions alone do not account for the soft tissues that can produce stenosis. Conventional radiographic findings may include an AP diameter of the spinal canal of 10 mm or less, facet joint arthritis, and spondylolisthesis (Fig. 24-13).

Conventional radiographic findings may include an AP diameter of the spinal canal of 10 mm or less, facet joint arthritis, and spondylolisthesis (Fig. 24-13). CT provides an excellent method of demonstrating bony abnormalities, but MRI is the best imaging modality for detecting lumbar spinal stenosis.

CT provides an excellent method of demonstrating bony abnormalities, but MRI is the best imaging modality for detecting lumbar spinal stenosis.

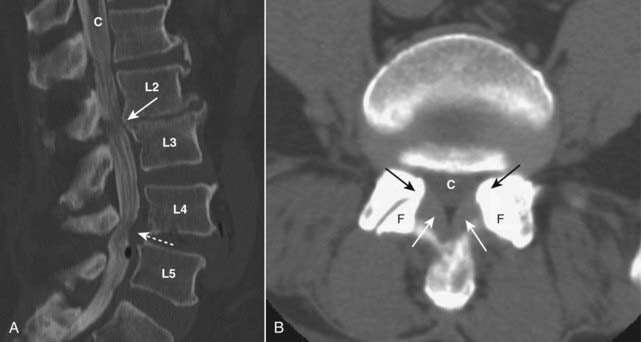

Figure 24-13 Spinal stenosis, CT.

A, At the level of L2-L3, there are osteophytes that narrow the canal (C) (solid white arrow). There is a protruding disk (dotted white arrow) at L4-L5 that reduces the size of the spinal canal at this level. B, The canal (C) is narrowed by thickening of the ligamenta flava (solid white arrows) and by bony overgrowth (solid black arrows) from osteoarthritis of the facet joints (F). Spinal stenosis refers to narrowing of the spinal canal or the neural foramina secondary to soft tissue or bony abnormalities.

Malignancy Involving the Spine

Metastases to bone are 25 times more common than primary bone tumors. Metastases usually occur where red marrow is found, with 80% of metastatic bone lesions occurring in the axial skeleton (i.e., spine, pelvis, skull, and ribs) because that is where, with normal aging, the red marrow exists.

Metastases to bone are 25 times more common than primary bone tumors. Metastases usually occur where red marrow is found, with 80% of metastatic bone lesions occurring in the axial skeleton (i.e., spine, pelvis, skull, and ribs) because that is where, with normal aging, the red marrow exists.

![]() Because of the rich blood supply in the posterior portion of vertebral bodies, hematogenous metastatic deposits to that part of the spine are common, especially from lung and breast carcinoma.

Because of the rich blood supply in the posterior portion of vertebral bodies, hematogenous metastatic deposits to that part of the spine are common, especially from lung and breast carcinoma.

In the spine, metastases may lead to compression fractures. Metastases tend to destroy the vertebral body, including and especially the posterior aspect and the pedicles, which is different from osteoporotic compression fractures in which the posterior vertebral body and pedicles remain intact (see Fig. 21-22).

In the spine, metastases may lead to compression fractures. Metastases tend to destroy the vertebral body, including and especially the posterior aspect and the pedicles, which is different from osteoporotic compression fractures in which the posterior vertebral body and pedicles remain intact (see Fig. 21-22). Metastatic disease can either be mostly bone-producing, i.e., osteoblastic, or mostly bone-destroying, i.e., osteolytic. Metastases that contain both osteolytic and osteoblastic processes occurring simultaneously are called mixed metastatic lesions.

Metastatic disease can either be mostly bone-producing, i.e., osteoblastic, or mostly bone-destroying, i.e., osteolytic. Metastases that contain both osteolytic and osteoblastic processes occurring simultaneously are called mixed metastatic lesions. Osteoblastic metastases will appear denser (whiter) than the surrounding normal bone on conventional radiographs. If focal, they may appear as punctate regions of increased density. When widespread, they may produce diffuse sclerosis of bone (see Fig. 21-3).

Osteoblastic metastases will appear denser (whiter) than the surrounding normal bone on conventional radiographs. If focal, they may appear as punctate regions of increased density. When widespread, they may produce diffuse sclerosis of bone (see Fig. 21-3). Prostate cancer is the prototype example of a primary malignancy that produces osteoblastic metastases; the prototype of such a primary malignancy in a female is breast cancer.

Prostate cancer is the prototype example of a primary malignancy that produces osteoblastic metastases; the prototype of such a primary malignancy in a female is breast cancer. Osteolytic metastases will appear less dense (blacker) than the surrounding normal bone on conventional radiographs. They destroy all or part of a bone, e.g., a portion of a bone may be absent, a rib may be destroyed, a pedicle may be missing.

Osteolytic metastases will appear less dense (blacker) than the surrounding normal bone on conventional radiographs. They destroy all or part of a bone, e.g., a portion of a bone may be absent, a rib may be destroyed, a pedicle may be missing. The most common causes of primary malignancies that produce osteolytic metastatic lesions are lung and breast cancer. Thyroid and renal carcinomas may produce osteolytic lesions that are also expansile (see Fig. 21-21).

The most common causes of primary malignancies that produce osteolytic metastatic lesions are lung and breast cancer. Thyroid and renal carcinomas may produce osteolytic lesions that are also expansile (see Fig. 21-21). The spine is also a frequent site of multiple myeloma, the most common primary malignancy of bone. Multiple myeloma is known for its tendency to produce almost totally lytic lesions. One of the hallmarks of multiple myeloma is osteoporosis, so that myeloma may be associated with diffuse spinal osteoporosis and multiple compression fractures (Fig. 24-14).

The spine is also a frequent site of multiple myeloma, the most common primary malignancy of bone. Multiple myeloma is known for its tendency to produce almost totally lytic lesions. One of the hallmarks of multiple myeloma is osteoporosis, so that myeloma may be associated with diffuse spinal osteoporosis and multiple compression fractures (Fig. 24-14).

Figure 24-14 Multiple myeloma of the spine.

One of the hallmarks of multiple myeloma is osteoporosis, so that myeloma may be associated with diffuse spinal osteoporosis (solid white arrows) and multiple compression fractures (L1-L5). Notice how the posterior aspects of the vertebral bodies remain essentially normal in height in osteoporotic fractures while the central and anterior aspects collapse.

![]() The current screening study of choice for the detection of spinal metastases is a Technetium-99m (Tc 99m) bone scintiscan (radionuclide bone scan). The technetium is most commonly bound to methylene diphosphonate (MDP) that transports the Tc 99m to bone. A radionuclide bone scan is relatively inexpensive, widely available, and screens the entire body. While bone scans are highly sensitive to the presence of metastatic deposits, they are not very specific. In many cases, a confirmatory study, usually a conventional radiograph, is needed to exclude other causes of abnormal radiotracer uptake such as fractures, infection, and arthritis (Fig. 24-15).

The current screening study of choice for the detection of spinal metastases is a Technetium-99m (Tc 99m) bone scintiscan (radionuclide bone scan). The technetium is most commonly bound to methylene diphosphonate (MDP) that transports the Tc 99m to bone. A radionuclide bone scan is relatively inexpensive, widely available, and screens the entire body. While bone scans are highly sensitive to the presence of metastatic deposits, they are not very specific. In many cases, a confirmatory study, usually a conventional radiograph, is needed to exclude other causes of abnormal radiotracer uptake such as fractures, infection, and arthritis (Fig. 24-15).

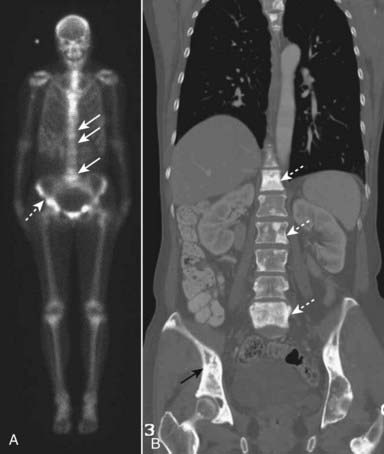

Figure 24-15 Metastases, radionuclide bone scan, and CT.

A, A Technetium-99m methylene diphosphonate (MDP) bone scan demonstrates abnormal tracer uptake in numerous areas including the spine (solid white arrows) and pelvis (dashed white arrow). Because of the nonspecific nature of positive bone scans, a confirmatory study, usually conventional radiography, is obtained as well. B, In this case the patient had undergone a CT scan and the coronal reformatted image shows numerous osteoblastic lesions in the spine (dotted white arrows) and the pelvis (solid black arrow) corresponding to the lesions seen on bone scan. This patient had known breast carcinoma.

Mri in Metastatic Spine Disease

MRI can detect changes of spinal metastases even earlier than a radionuclide scan, and techniques are being described that may allow for a rapid, whole-body screening similar to radionuclide bone scanning.

MRI can detect changes of spinal metastases even earlier than a radionuclide scan, and techniques are being described that may allow for a rapid, whole-body screening similar to radionuclide bone scanning.

![]() With neoplastic infiltration of the bone marrow, there is a decrease in the normally high signal of the vertebrae on T1-weighted images and there is usually a high signal on T2-weighted images (Fig. 24-16).

With neoplastic infiltration of the bone marrow, there is a decrease in the normally high signal of the vertebrae on T1-weighted images and there is usually a high signal on T2-weighted images (Fig. 24-16).

Unlike osteoporotic compression fractures which tend to spare the posterior aspects of the bodies while the central and anterior portions collapse, spinal metastases will more often affect the entire body including the posterior portion.

Unlike osteoporotic compression fractures which tend to spare the posterior aspects of the bodies while the central and anterior portions collapse, spinal metastases will more often affect the entire body including the posterior portion.

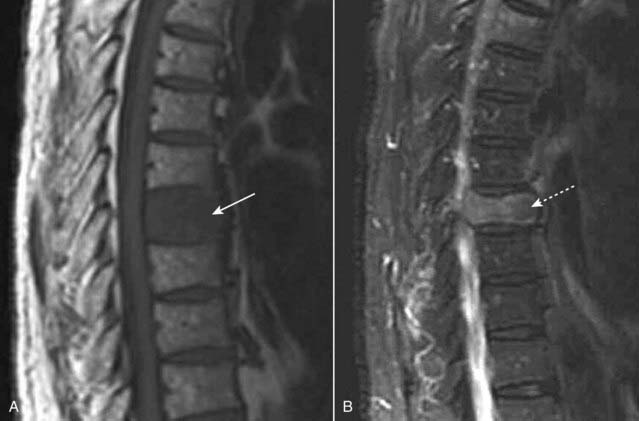

Figure 24-16 Metastases to the spine, MRI.

A, T1-weighted sagittal MRI of the thoracic spine demonstrates marrow replacement in the T8 vertebral body (solid white arrow). The signal is decreased compared to the normal bodies above and below it. B, T2-weighted sagittal MRI shows abnormally high signal in the compressed vertebral body (dotted white arrow). The entire vertebral body is involved. The patient had primary breast carcinoma.

Infections of the Spine: Diskitis and Osteomyelitis

Spinal infection is usually due to Staphylococcus. It is also frequently caused by Enterobacter. In adults, infection most often occurs subsequent to spinal instrumentation such as surgery or spinal tap. In children, the disease is usually hematogenously spread.

Spinal infection is usually due to Staphylococcus. It is also frequently caused by Enterobacter. In adults, infection most often occurs subsequent to spinal instrumentation such as surgery or spinal tap. In children, the disease is usually hematogenously spread. In children, the disk is involved directly most often. In adults, the vertebral body endplates are usually involved first (osteomyelitis) and infection will then spread to the adjacent intervertebral disk (diskitis).

In children, the disk is involved directly most often. In adults, the vertebral body endplates are usually involved first (osteomyelitis) and infection will then spread to the adjacent intervertebral disk (diskitis). An exception to this pattern can be tuberculosis, which can affect multiple vertebral bodies without involvement of the disks because the infection spreads silently beneath the longitudinal ligaments of the spine.

An exception to this pattern can be tuberculosis, which can affect multiple vertebral bodies without involvement of the disks because the infection spreads silently beneath the longitudinal ligaments of the spine. Epidural abscess or phlegmon may form due to direct extension into, or hematogenous seeding of, the epidural space. Epidural abscesses are potentially life threatening and have a significant morbidity.

Epidural abscess or phlegmon may form due to direct extension into, or hematogenous seeding of, the epidural space. Epidural abscesses are potentially life threatening and have a significant morbidity. Recognizing vertebral body osteomyelitis and diskitis on MRI (Fig. 24-17).

Recognizing vertebral body osteomyelitis and diskitis on MRI (Fig. 24-17).

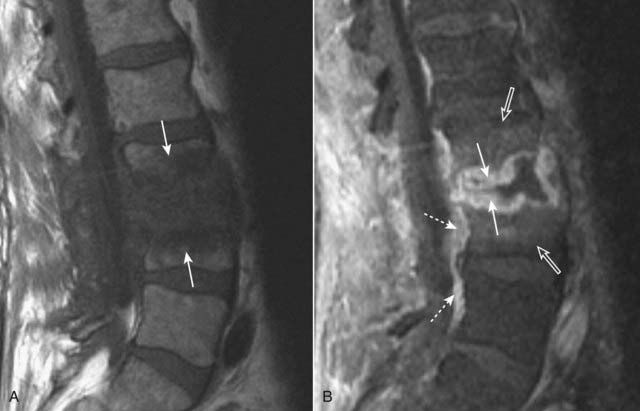

Figure 24-17 Osteomyelitis and diskitis, lumbar spine.

A, Sagittal T1-weighted image demonstrates extensive abnormal T1-dark signal indicating destruction of the endplates of the L3 and L4 vertebral bodies and the intervening disk (solid white arrows). B, Sagittal T1-weighted postgadolinium image demonstrates abnormal disk enhancement (solid white arrows) and, more importantly for this diagnosis, enhancement of the adjacent L3 and L4 vertebral bodies (open white arrows). In addition, there is extension to the anterior epidural space (dotted white arrows).

Spinal Trauma

Fractures of the spine are infrequent compared to fractures of other parts of the skeleton. When they occur, they have particular importance because of the implications for associated spinal cord injury. The most commonly fractured vertebrae are L1, L2, and T12, accounting for more than half of all thoracolumbar spine fractures. In the thoracic spine, compression fractures are the most common type of spinal fracture.

Fractures of the spine are infrequent compared to fractures of other parts of the skeleton. When they occur, they have particular importance because of the implications for associated spinal cord injury. The most commonly fractured vertebrae are L1, L2, and T12, accounting for more than half of all thoracolumbar spine fractures. In the thoracic spine, compression fractures are the most common type of spinal fracture. The three cervical lines (see Fig. 24-2).

The three cervical lines (see Fig. 24-2).

![]() At the beginning of this chapter, we talked about the three cervical lines. Three parallel arcuate lines should smoothly join (1) all of the spinolaminar white lines (the junction between the lamina and the spinous process), (2) all of the posterior aspects of the vertebral bodies, and (3) all of the anterior aspects of the vertebral bodies.

At the beginning of this chapter, we talked about the three cervical lines. Three parallel arcuate lines should smoothly join (1) all of the spinolaminar white lines (the junction between the lamina and the spinous process), (2) all of the posterior aspects of the vertebral bodies, and (3) all of the anterior aspects of the vertebral bodies.

Deviation from the normal parallel curvature of these lines should suggest a subluxed or fractured vertebral body.

Deviation from the normal parallel curvature of these lines should suggest a subluxed or fractured vertebral body.Jefferson’s Fracture

A Jefferson’s fracture is a fracture of C1 usually involving both the anterior and posterior arches. In its classical presentation, there are bilateral fractures of both the anterior and posterior arches of C1 producing four fractures in all.

A Jefferson’s fracture is a fracture of C1 usually involving both the anterior and posterior arches. In its classical presentation, there are bilateral fractures of both the anterior and posterior arches of C1 producing four fractures in all. It is caused by an axial loading injury (such as diving into a swimming pool and hitting one’s head on the bottom).

It is caused by an axial loading injury (such as diving into a swimming pool and hitting one’s head on the bottom).

![]() On conventional radiographs, the hallmark of a Jefferson fracture is bilateral, lateral offset of the lateral masses of C1 relative to C2 as seen on the open-mouth view (atlantoaxial view) of the cervical spine. The fracture is confirmed utilizing CT (Fig. 24-18).

On conventional radiographs, the hallmark of a Jefferson fracture is bilateral, lateral offset of the lateral masses of C1 relative to C2 as seen on the open-mouth view (atlantoaxial view) of the cervical spine. The fracture is confirmed utilizing CT (Fig. 24-18).

A Jefferson’s fracture is a “self-decompressing” fracture in that the spinal canal at the level of the fracture is wide enough to accommodate any swelling of the cord. There is usually no neurologic deficit associated with this type of fracture.

A Jefferson’s fracture is a “self-decompressing” fracture in that the spinal canal at the level of the fracture is wide enough to accommodate any swelling of the cord. There is usually no neurologic deficit associated with this type of fracture.

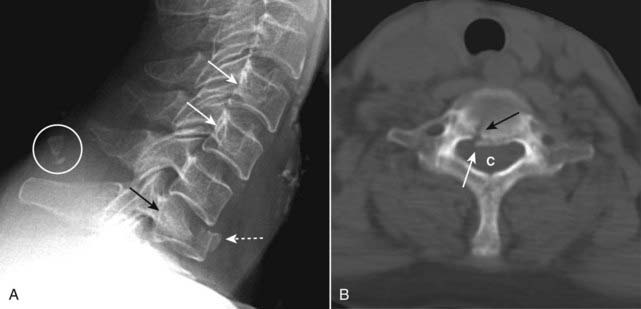

Figure 24-18 Normal open-mouth view, Jefferson’s fracture open-mouth view, and CT.

A Jefferson’s fracture is a fracture of C1 usually involving both the anterior and posterior arches. A, The normal “open-mouth” view of C1 and C2 demonstrates that the lateral margins of C1 (solid white arrows) line up with the lateral margins of C2. B, The hallmark of a Jefferson’s fracture is bilateral, lateral offset of the lateral masses of C1 (solid white arrows) relative to C2. C, The fracture is confirmed utilizing CT, which shows fractures of both the right and left anterior arch and the right posterior arch of C1 (dotted white arrows).

Hangman’s Fracture

Hangman’s fractures result from a hyperextension-compression injury typically occurring in an unrestrained occupant in a motor vehicle accident who strikes his forehead on the windshield.

Hangman’s fractures result from a hyperextension-compression injury typically occurring in an unrestrained occupant in a motor vehicle accident who strikes his forehead on the windshield. They are best evaluated on the lateral view of the cervical spine on conventional radiography and the sagittal view on CT.

They are best evaluated on the lateral view of the cervical spine on conventional radiography and the sagittal view on CT.

![]() The fracture effectively separates the posterior aspect of the C2 vertebral body from the anterior aspect of C2 allowing the anterior aspect of C2 to sublux forward on the body of C3 (Fig. 24-19).

The fracture effectively separates the posterior aspect of the C2 vertebral body from the anterior aspect of C2 allowing the anterior aspect of C2 to sublux forward on the body of C3 (Fig. 24-19).

Figure 24-19 Hangman’s fracture.

A hangman’s fracture results from a hyperextension-compression injury. It involves fractures through the posterior elements of C2 best evaluated on the lateral view. The fracture (dotted white arrow shows fracture line) effectively separates the posterior aspect of the C2 vertebral body from the anterior aspect of C2 allowing the anterior aspect to sublux forward on the body of C3. Notice that the spinolaminar line of C2 lies posterior to the other vertebral bodies (solid black arrow) and the anterior aspect of C2 lies forward of the anterior body of C3 (solid white arrow).

Because hangman fractures lead to overall widening of the bony canal, they are usually not associated with neurologic deficits. This is in contradistinction to the injury after which this fracture is named, the fracture incurred during a judicial hanging in which there was hyperextension leading to a fracture of C2 and marked distraction of C2 from C3 associated with distraction of the spinal cord itself.

Because hangman fractures lead to overall widening of the bony canal, they are usually not associated with neurologic deficits. This is in contradistinction to the injury after which this fracture is named, the fracture incurred during a judicial hanging in which there was hyperextension leading to a fracture of C2 and marked distraction of C2 from C3 associated with distraction of the spinal cord itself.Burst Fractures

Burst fractures can occur at any level but are most common in the cervical spine, thoracic spine, and upper lumbar spine.

Burst fractures can occur at any level but are most common in the cervical spine, thoracic spine, and upper lumbar spine. They are high-energy axial loading injuries, typically secondary to motor vehicle accidents or falls, in which the disk above is driven into the vertebral body below and the vertebral body bursts. This in turn drives bony fragments posteriorly into the spinal canal (retropulsed fragments) while the anterior aspect of the vertebral body is displaced forward.

They are high-energy axial loading injuries, typically secondary to motor vehicle accidents or falls, in which the disk above is driven into the vertebral body below and the vertebral body bursts. This in turn drives bony fragments posteriorly into the spinal canal (retropulsed fragments) while the anterior aspect of the vertebral body is displaced forward. Because these fractures involve incursion on the spinal canal, the majority of burst fractures are associated with a neurologic deficit.

Because these fractures involve incursion on the spinal canal, the majority of burst fractures are associated with a neurologic deficit.

![]() Findings of burst fractures include a comminuted, compression fracture of the vertebral body in which the posterior aspect of the body is bowed backward toward the spinal canal. CT is the best imaging modality for identifying bony fragments in the spinal canal (Fig. 24-20).

Findings of burst fractures include a comminuted, compression fracture of the vertebral body in which the posterior aspect of the body is bowed backward toward the spinal canal. CT is the best imaging modality for identifying bony fragments in the spinal canal (Fig. 24-20).

Figure 24-20 Burst fracture, radiograph, and CT.

A, Findings include a comminuted, compression fracture of the vertebral body in which the anterior vertebral body is displaced forward (dotted white arrow) while the posterior aspect of the body is propelled dorsally toward the spinal canal (solid black arrow). Notice how the posterior aspects of vertebral bodies are normally concave inward (solid white arrows). Calcification of the ligamentum nuchae is of no clinical consequence (white circle). B, Axial CT scan of the spine shows a fracture of the body (solid black arrow) and the retropulsed fragment (solid white arrow) protruding into the spinal canal (C).

Locked Facets

Bilateral locking of the facets in the cervical spine can occur as a result of a hyperflexion injury in which the inferior facets of one vertebral body slide over and in front of the superior facets of the body below. In this position, the slipped facets cannot return to their normal position without medical intervention; thus, the term “locked.”

Bilateral locking of the facets in the cervical spine can occur as a result of a hyperflexion injury in which the inferior facets of one vertebral body slide over and in front of the superior facets of the body below. In this position, the slipped facets cannot return to their normal position without medical intervention; thus, the term “locked.” Locked facets occur with forward slippage of the affected vertebral body on the body below it by at least 50% of its AP diameter.

Locked facets occur with forward slippage of the affected vertebral body on the body below it by at least 50% of its AP diameter.

![]() On lateral (sagittal) imaging of the cervical spine, the inferior articular facets will lie in front of the superior facets of the body below. This is the reverse of the normal anatomic relationship between adjacent facets (Fig. 24-21).

On lateral (sagittal) imaging of the cervical spine, the inferior articular facets will lie in front of the superior facets of the body below. This is the reverse of the normal anatomic relationship between adjacent facets (Fig. 24-21).

Since the superior articular facets are no longer “covered” by the inferior facets above them, this appearance was described on CT as the naked facet sign.

Since the superior articular facets are no longer “covered” by the inferior facets above them, this appearance was described on CT as the naked facet sign.

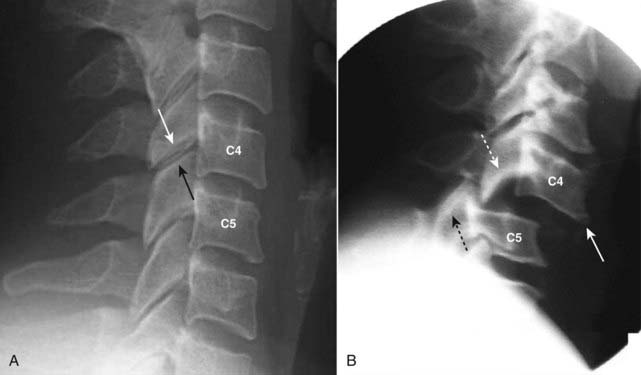

Figure 24-21 Normal and bilateral locked facets.

A, Normally, the inferior articular facet of the body above (in this case C4, solid white arrow) lies posterior to the superior articular facet of the body below (in this case C5, solid black arrow). B, The inferior articular facet of C4 (dotted white arrow) lies anterior to the superior articular facet of C5 (dotted black arrow), the reverse of normal. Locking of the facets in the cervical spine can occur as a result of a hyperflexion injury that results in forward slippage of the affected vertebral body on the body below it by at least 50% of its AP diameter (solid white arrow).

Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Recognizing Some Common Causes of Neck and Back Pain on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Recognizing Some Common Causes of Neck and Back Pain

Conventional radiographs, CT, and MRI are all used to evaluate the spine, but MRI is the study of choice for most diseases of the spine because of its superior ability to display soft tissues.

Normal features of the vertebral bodies, intervertebral disks, the spinal cord, spinal nerves, and spinal ligaments are described.

Some of the more common causes of back pain are muscle and ligament strain, herniation of an intervertebral disk, degeneration of an intervertebral disk, arthritis involving the synovial joints of the spine, compression fractures from osteoporosis, trauma to the spine, and malignancy involving the spine.

Most herniated disks occur posterolaterally in the lower cervical or lower lumbar spine and are best evaluated using MRI.

Postlaminectomy syndrome is persistent pain in the back or legs following spine surgery. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI can be very helpful in detecting the cause.

With increasing age, the nucleus pulposus becomes dehydrated and degenerates, leading to changes of degenerative disk disease such as progressive loss of the height of the disk space, marginal osteophyte production, sclerosis of the endplates of the vertebral bodies, and occasionally the appearance of a vacuum disk.

The facet joints are true joints and are subject to changes of osteoarthritis; facet osteoarthritis is frequently associated with degenerative disk disease and can lead to radicular pain.

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis is manifest by thick, bridging or flowing calcification/ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament usually occurring in men over the age of 50. The disk spaces and the facet joints are usually preserved.

Compression fractures of the spine are most often secondary to osteoporosis and are seen more commonly in women. They can be seen on conventional radiographs and, because they usually disproportionately involve the anterior portion of the body, produce an exaggerated kyphosis in the thoracic spine.

Spondylolisthesis is defined as slippage (typically forward) of one vertebral body (and the spine above it) on another; in general it is caused by either bilateral breaks in the pars interarticularis (spondylolysis) or osteoarthritis of the facet joints (degenerative spondylolisthesis).

Spondylolysis is believed secondary to a congenitally dysplastic pars interarticularis which eventually develops a stress fracture; when this occurs, the vertebral body is able to slip forward on the body below it.

Degenerative spondylolisthesis, which is most common at L4-L5, may occur through a complex interaction between the ligaments, disks, and facet joints; there is no break in the pars interarticularis, and the degree of slip is usually less than that seen with spondylolysis.

Spinal stenosis is a narrowing of the spinal canal or the neural foramina secondary to soft tissue or bony abnormalities, either on an acquired or, less commonly, congenital basis; it occurs most frequently in the cervical and lumbar regions.

Metastatic lesions to the spine are common, especially to the blood-rich posterior aspect of the vertebral body including the pedicles; lung (mixed), breast (mixed), and prostate (osteoblastic) metastases are the most common.

Multiple myeloma also frequently involves the spine either with severe osteoporosis, which can produce compression fractures, or lytic destruction of the vertebral body.

Infection of the spine usually starts in the vertebral body endplates in adults and then involves the adjacent disk. Think of diskitis when a process involves two adjacent vertebral bodies and the intervening disk.

Three parallel arcuate lines should smoothly connect important landmarks on the lateral cervical spine view and allow for a quick assessment for fracture or subluxation before the patient is moved for further studies.

The findings in a Jefferson fracture, hangman fracture, burst fracture, and locked facets are discussed; the first two are self-decompressing injuries that are usually not associated with neurologic deficit while the latter two are frequently associated with neurologic impairment.