Chapter 3 Dermatological conditions of the foot and leg

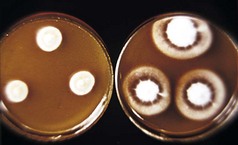

Laboratory diagnosis of dermatophyte infection

Systemic treatment of foot and nail infections

Inflammatory skin diseases

Several chronic inflammatory skin diseases commonly involve the feet. A podiatrist should be able to recognise the clinical features of the most common skin diseases and be aware of appropriate management and referral criteria.

PSORIASIS AND RELATED DISORDERS

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin condition with a prevalence of about 2% of the UK population (Griffiths & Barker 2007). It can affect any age group, including children, but onset is commonest in early adulthood and late middle age. The disease is characterised by increased turnover of the epidermis, but the pathogenesis involves abnormalities in T-lymphocyte function and increased vascularity, as well as proliferation and altered differentiation of keratinocytes. There is clear evidence to suggest that susceptibility to psoriasis is inherited; a number of genetic loci have been implicated but the precise genetic basis of the disease is not yet known (Ortonne 1999).

Chronic plaque psoriasis is the most characteristic form. Patients present with circumscribed itchy patches of thick, scaly, red skin often prominent on the elbows, knees and scalp, although any body site can be affected (Fig. 3.1). Other variants include:

Figure 3.1 A typical plaque of chronic plaque psoriasis. These plaques are normally found on the limbs.

Psoriasis can be triggered or exacerbated by a number of factors, which include: trauma (psoriasis appearing at sites of injury such as operative scars is called the Köbner phenomenon); drugs, such as lithium or hydroxychloroquine; infection, particularly the streptococcal pharyngitis, which triggers guttate psoriasis (see above); and stress, which does appear to be important in disease exacerbations in some patients. As with many chronic diseases, patients with severe psoriasis have increased cardiovascular morbidity, and are more prone to psychological problems, including alcoholism. About 40% of women with psoriasis improve during pregnancy while 15% deteriorate.

The severity of psoriasis can be assessed by the PASI (psoriasis area and severity index) score. This is useful in measuring objective response in clinical trials, in which 75% improvement (PASI 75) is a commonly used an endpoint. However, the PASI is mainly a measure of extent and fails to take account of many other factors; it is often supplemented by the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).

The feet are commonly involved in psoriasis. Typical pink or red plaques with a superficial layer of fine silvery white scale may be seen on the dorsum of the foot, while more hyperkeratotic, fissured skin is seen on the plantar surface, particularly at sites of pressure. Psoriasis commonly also causes nail dystrophy, including separation of the nail plate from the nail bed (onycholysis) or subungual hyperkeratosis. Fine indentations or pitting of the nail plate may also be seen; this is more prominent on fingernails. Psoriatic arthritis may be an additional problem, and can present with pain and decreased mobility in the axial skeleton and the small joints of the hands and feet. A rare mutilating form of arthritis can result in significant resorption of bone in the digits.

Differentiating plantar psoriasis from other causes of acquired plantar keratoderma (thickening of the plantar skin), such as eczema, lichen planus and fungal infection, is often difficult. It is therefore important to look for typical signs of psoriasis at other sites and to enquire about a positive family history of the disease.

Treatment

Regular emollients reduce scaling and fissuring, and keratolytics such as 5% salicylic acid in Vaseline or 50% propylene glycol in water treat hyperkeratosis. The numerous active topical treatments available include vitamin D analogues such as calcipotriol, topical steroids, coal-tar-based preparations, dithranol (anthralin), an anthraquinone compound, and vitamin A derived drugs (retinoids).

Patients may benefit from treatment with ultraviolet B (UVB) phototherapy, or photochemotherapy using an oral or topical photoactive drug (a psoralen) in combination with ultraviolet A (PUVA). This treatment can be localised by using hand and foot irradiation units. More severe cases may require treatment with drugs such as the oral retinoid acitretin, or immunosuppressive agents such as methotrexate or ciclosporin (Warren & Griffiths 2008). The latter two agents in particular carry significant toxicity risks for bone marrow, liver or kidney, and all long-term systemic agents for psoriasis necessitate monitoring. Patients with severe psoriasis not suitable for these drugs or who respond poorly may be treated with biological agents (Smith et al 2005). These include the TNF-alpha antagonists etantercept, infliximab, and adalimumab. These agents carry the risks of immunosuppression, and are currently very expensive. Biological agents with other targets are licensed or under development for psoriasis and psoriatic arthropathy.

Palmoplantar pustular psoriasis (PPP)

Many patients with this chronic inflammatory disorder of the palms and soles have no other features of psoriasis and hence there is some debate as to whether it is a true subtype of the disorder. It typically presents with red scaly hyperkeratotic palmar and plantar skin studded with sterile pustules (Fig. 3.2). Fresh pustules initially appear yellow and subsequently dry to leave brown discoloration. Extensive plantar disease can result in pain on weight-bearing. PPP is more common in middle-aged women and is strongly associated with cigarette smoking. The differential diagnosis includes acute infected eczema, dermatophyte fungal infection and Reiter’s disease (see below). Treatment of PPP is similar to that of psoriasis but the disease is often resistant to many of the available therapeutic options (Eriksson et al 1998).

REITER’S DISEASE

This is a reactive disorder in which arthritis, urethritis, conjunctivitis and inflammatory mucocutaneous disease are triggered by urogenital or gut infections. It is most commonly seen in young men in whom it often follows Chlamydia trachomatis urethritis.

The classic cutaneous finding is keratoderma blenorrhagicum, a psoriasis-like eruption that usually affects the soles of the feet and may not appear for several months after the onset of arthritis and conjunctivitis. Affected patients have thick, ‘limpet-like’ hyperkeratoses with a dull yellow discoloration or a more acute pustular rash.

Patients with active systemic disease may require treatment with immunosuppressive drugs such as methotrexate or azathioprine, which may also improve the cutaneous features of the disease. Application of emollients and keratolytics may reduce the plantar keratoderma.

PITYRIASIS RUBRA PILARIS (PRP)

This is a rare group of disorders characterised by hyperkeratosis of hair follicles, widespread erythema and palmoplantar keratoderma. The cause of PRP is unknown.

In the classic form, erythema surrounding individual hair follicles spreads out to become confluent, although there are typically islands of spared normal-appearing skin. The erythema has a distinctive orange-yellow hue, which is particularly prominent in the hyperkeratotic skin of the palms and soles. The disorder is often difficult to differentiate from psoriasis. Patients are generally treated with bland emollients, although many subsequently require the addition of systemic agents such as acitretin or methotrexate. Response to treatment is often poor but the disease generally resolves spontaneously (Griffiths 1980).

ECZEMA (DERMATITIS) AND RELATED DISORDERS

Dermatitis is an inflammatory skin disease that may be caused by a number of factors. For most purposes the terms ‘eczema’ and ‘dermatitis’ are synonymous. Acute dermatitis is characterised by redness, scaling and weeping, often with vesiculation (tiny fluid-filled blisters). In contrast, chronic dermatitis is characterised by excoriation (scratch marks) and thickening of the skin known as ‘lichenification’. Common categories of eczema include those described below.

CASE STUDY 3.1 ECZEMA/DERMATITIS – OUTLINE OF DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT

A boy aged 8 years and a keen swimmer had to stop this activity as he developed thin plantar skin on both feet which fissured easily, becoming painful and prone to infection. There was no family history of similar problems, but his mother recalled that he developed a red itchy rash (urticaria) the previous summer. He had treated it with a number of topical preparations without success. Previously the skin problem had occurred around the toes but now the site and skin changes followed the shoe/skin contact line, which suggested an allergy to the dye and/or adhesive in the footwear. Differential diagnosis included tinea pedis, hyperhidrotic skin (sweaty skin that dries quickly on exposure, becoming dry and scaly – xerosis), juvenile plantar dermatosis and atopic dermatitis (Leung 1998). Laboratory microscopy and culture of scrapings showed no evidence of fungal infection.

The treatment was symptomatic, as no clear diagnosis was evident. Fissures were closed with adhesive skin closures or medical-grade acrylic glue (with prior patch testing, although this cannot be relied upon). While waiting for the laboratory report, the patient’s mother spent some time isolating the suspected allergen. The patient’s socks were washed in water only, all topical applications were stopped and the shoes suspected of being implicated were not worn for 5 weeks to allow the apparent hypersensitivity to subside. There was a marked improvement after 2 weeks and a gradual introduction of the suspected allergens identified a particular pair of shoes, which were discarded. The patient could have been referred to the allergy clinic for tests, but this simple method of identifying a potential allergen was an attractive option given the time delay in referral.

Further aspects of management to prevent recurrence included distancing the patient’s skin from potential allergens, and the control of any hyperhidrosis. Water enhances percutaneous absorption of many topical substances, and a sweaty environment provides an opportunity for enhanced bacterial colonisation of the skin and increased potential for bacterial superantigen associated with atopy (Leung 1998). The boy’s mother contacted the shoe manufacturers to enquire about products used in manufacture; a barrier cream was applied to the patient’s feet (e.g. silicone). Sweat-absorbing socks and charcoal-impregnated insoles were also used by the patient.

It is difficult to say whether one or all of these management methods were responsible for the success in the relief of the patient’s symptoms. In this particular case it was neither good clinical practice nor ethical to withhold treatment to determine which was the most successful.

Atopic eczema

This is a common, chronically relapsing skin disease with a genetic predisposition and a rising prevalence in the population. It is often associated with the other atopic diseases, asthma and hay fever. Onset is usually in infancy, and about 60% of children are clear of dermatitis by the age of 10 years. In a minority, eczema persists into adult life, and others may present for the first time later in life. The cause is complex and multifactorial, but a major underlying factor is a defective skin barrier. Many patients with atopic eczema carry null mutations in the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin (Sandilands et al 2007). Defects in the skin barrier may be responsible for the altered immune reactivity to common environmental allergens such as the house dust mite. Atopic eczema can affect any body site but is particularly common on the flexural surfaces of limbs and on the face. Involvement of the feet is less common, although the ankles are often affected (Fig. 3.3). Patients with defects in filaggrin are more likely to show hyperlinearity and hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles.

Figure 3.3 A 3-year-old child of with severe atopic eczema showing erythema and coarse skin markings (lichenification) of the feet.

Treatment

The mainstay of treatment is a combination of regular emollients (moisturisers) and topical corticosteroid ointments or creams. These vary in potency from the mild hydrocortisone, to the more potent synthetic fluorinated corticosteroids, which in prolonged use cause skin atrophy. Topical immunosuppressive agents (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus) are a more recent alternative to topical corticosteroids. Anti-inflammatory pastes containing tars such as ichthammol, or zinc, are particularly effective in settling eczema of the feet and ankles. Affected skin is often infected by Staphylococcus aureus, and antiseptic or topical or oral antibiotic may be needed. Patients with severe chronic eczema may require treatment with immunosuppressive drugs such as azathioprine or ciclosporin; phototherapy is also used (Brehler et al 1997).

Contact dermatitis

Contact dermatitis can be subdivided into patients who have a hypersensitivity reaction to specific allergens (allergic contact dermatitis) and those who have a non-specific reaction to irritants (irritant contact dermatitis), but the two often coexist.

Irritant contact dermatitis is usually the result of non-allergic, chemical damage to the skin. This may occur acutely, for instance after exposure to acids or alkalis, but is more commonly the result of cumulative exposure to a variety of irritants such as soaps, detergents and even water. Workers in jobs where wet work is common are particularly prone to irritant contact dermatitis. Some workers are far more prone to the effects of irritants than others, although the reason for this is not clear. The hands are the most common site of irritant contact dermatitis.

Allergic contact dermatitis is an important cause of dermatitis of the feet. Patients may become sensitised (allergic) to a wide variety of allergens present in footwear, hosiery and even topical medicaments (Fig. 3.4). In footwear dermatitis, the commonest sources of allergens are chrome (used in leather tanning), rubber vulcanising agents, adhesives (e.g. colophony) and textile dyes. On repeated exposure to such allergens, a contact dermatitis develops. Sometimes a distinctive pattern of dermatitis, with a sharp demarcation between normal and affected skin, will point to allergic contact hypersensitivity as a possible cause.

Figure 3.4 Allergic contact dermatitis of the soles of the feet due to sensitivity to mercaptobenzothiazole, a rubber additive.

Patch testing with standardised concentrations of allergens may identify the source of allergic contact dermatitis. This procedure involves application of a series of allergens to the back under adhesive tape. Patches are removed after 48 hours and reactions read at 48 and 96 hours; positive tests are identified as individual red papular or vesicular reactions. In assessing footwear dermatitis, patch tests with samples from different parts of a patient’s shoe may be useful (Cockayne et al 1998).

CASE STUDY 3.2 SENSITIVITY TO COLOPHONY

This man was treated with adhesive strapping support for a sprained ankle. Within 48 hours he developed an acute vesicular and weeping eczema (here being treated with potassium permanganate soaks). Patch testing revealed sensitivity to colophony, a common resinous material found in adhesives.

Stasis and varicose eczema

Chronic venous or lymphatic insufficiency may cause dermatitis. The classic distribution of venous or varicose eczema is on the gaiter area of the leg (lower shin and calf), although it can also extend onto the foot. There is often a history of varicose veins or of deep vein thrombosis. Oedema, increased pigmentation (haemosiderin deposition), purpura and ulceration are often present with the dermatitis. Chronic venous hypertension causes distended veins to develop a fibrin cuff, which inhibits movement of fluid, nutrients and metabolites (Hoffman 1997), resulting in poor tissue viability and mechanical weakness (Dealey 2005). Atrophie blanche (white, scarred skin) may be present, and such skin is especially vulnerable to ulceration.

Dermatitis may also complicate chronic oedema due to cardiac or renal insufficiency, obesity, immobility or lymphatic disease. Often these are present in combination. In lymphoedema a firm non-pitting oedema is present, and dilated lymph vessels may give a cobbled appearance to the skin; there may also be a wary hyperkeratosis of the feet. Lymphoedematous legs are vulnerable to recurrent cellulitis, which in turn causes further lymphatic damage.

Allergic contact dermatitis may complicate up to 50% of cases of stasis dermatitis, with hypersensitivity to preservatives and other ingredients in topical medicaments and rubber in bandages being common. The treatment of choice is graduated elastic compression in the form of bandaging or stockings.

Pompholyx

This is a striking acute vesicular type of dermatitis that affects the palms (cheiropompholyx) and the soles of the feet (podopompholyx). The aetiology of pompholyx is unclear, although some studies have suggested a prevalence of atopy in up to 50% of sufferers. Patients complain of intense itching and discomfort and examination reveals multiple tiny vesicles that look like sago grains (Fig. 3.5). The role of contact allergy in pompholyx is debated, although some investigators believe that ingested nickel may be a factor in nickel-sensitive patients. Treatment is aimed at drying the acute, weeping vesicles with potassium permanganate soaks and reducing the inflammatory component with potent topical steroid creams (Burton & Holden 1998).

Juvenile plantar dermatosis

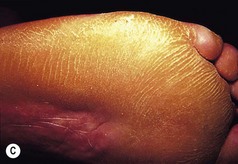

This is probably a type of irritant plantar dermatitis that occurs almost exclusively in children aged between 3 and 14 years and is more common in atopics. It presents with fissured, dry dermatitis on the forefoot and heel, with a typical glazed red appearance (Fig. 3.6). Again, the cause is not clear although there have been suggestions that excess humidity in shoes made from modern non-porous materials, such as trainers, might be responsible. The differential diagnosis includes allergic contact dermatitis and fungal infection. Most cases clear spontaneously but some patients benefit from regular emollients and avoidance of synthetic footwear. Cork insoles are anecdotally of value (Lemont & Pearl 1992).

LICHEN PLANUS

Lichen planus (LP) is an intensely itchy inflammatory skin condition which appears to be immunologically mediated, although the exact cause is not clear. Some cases are associated with adverse reactions to drugs such as gold, while other cases have been reported in patients infected with hepatitis B and C viruses.

Patients classically present with itchy, polygonal, violaceous, flat-topped papules covered with superficial white lines known as Wickham’s striae. Papules may coalesce into plaques, and lesions can appear in lines of trauma (another example of the Koebner phenomenon). The rash can affect any body site, although lesions on the wrists and ankles are particularly common. In addition, LP can cause nail dystrophy, scarring alopecia and can affect oral and genital mucosa.

LP can affect plantar skin and the lesions are often not characteristic of LP lesions at other sites. A spectrum of disease may be seen ranging from a few discrete papules at the margin of the foot to widespread hyperkeratosis with fissuring and ulceration (Fig. 3.7).

LP is usually a self-limiting disease, although it may occasionally persist for years. The treatment of choice for widespread, severe disease is systemic steroids, although more limited disease may respond well to potent topical steroids. Hyperkeratotic plantar involvement should be treated with combinations of keratolytics, such as salicylic acid, and potent topical steroids. Oral steroids or ciclosporin can be added in difficult cases (Boyd & Neldner 1991).

ICHTHYOSIS

‘Dry skin’, or ichthyosis, of varying degrees is common in the population. Skin becomes more rough and scaly with age due to a reduction in lipid synthesis, and this may be exacerbated by medications or disease. Genetically determined types of ichthyosis also occur, of which the commonest is ichthyosis vulgaris, due to homozygosity for null mutations in the stratum corneum keratin filament aggregating protein filaggrin (Sandilands et al 2007). Other genetic causes include a lack of cholesterol processing due to steroid sulfatase deficiency in X-linked ichthyosis. Ichthyosis affecting the feet may be manifest by both hyperkeratosis and hyperlinearity.

KERATODERMAS

Plantar skin is characterised by a markedly thickened outer horny layer, or stratum corneum, that provides a functional advantage in protecting the foot against the effects of chronic trauma. This becomes particularly apparent when comparing the feet of people who walk barefoot with those who do not. In addition to this physiological spectrum in the thickness of plantar skin, there are a number of pathological disorders that result in plantar hyperkeratosis or keratoderma. It is not uncommon for podiatrists to see patients presenting with plantar keratoderma, and this section will attempt to classify this heterogeneous group of disorders and define their clinical features and the options available for treatment.

Broadly speaking, the palmoplantar keratodermas (PPKs) can be divided into inherited or acquired varieties, the latter being associated with inflammatory skin diseases such as eczema or psoriasis (see above), or a variety of other or uncertain aetiologies.

Inherited palmoplantar keratodermas

This is a group of rare genetic skin diseases that are characterised by variable degrees of palmar and plantar hyperkeratosis, often in association with other clinical features that make up a syndrome. There have been a number of attempts to classify these diseases based on the pattern of hyperkeratosis (diffuse, focal or punctate), histological features, mode of inheritance and, more recently, by identifying the underlying gene mutation. The latter technique may provide evidence for the molecular basis of these diseases and may have practical implications for both future prenatal diagnosis and gene-targeted therapy.

A detailed review of all the inherited PPKs is beyond the scope of this text, and interested readers are directed to reviews such as that by Kimyai-Asadi et al (2002).

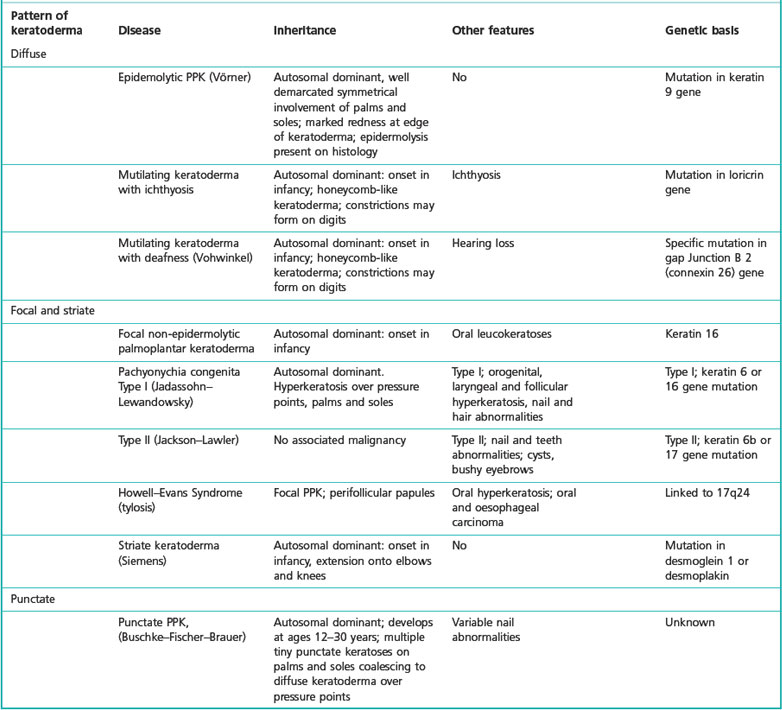

For practical, clinical purposes it is helpful to classify inherited PPKs according to the pattern of hyperkeratosis and the presence or absence of other associated diseases (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1 Examples of inherited palmoplantar keratoderma and their causes (Judge et al 2004)

Aetiology

Recent research has identified mutations in a variety of mainly structural genes of the epidermis that have been found in different patterns of keratoderma. These include keratins, a group of structural proteins with a range of properties that are expressed in specific patterns in different areas of the skin. Other keratodermas are due to mutations in proteins involved in cell adhesion, and in forming the cornified envelope, the waterproof outer layer of the epidermis.

Clinical features

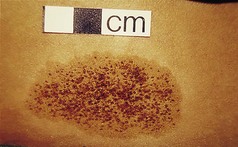

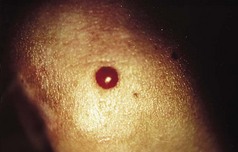

The features of some inherited PPKs are outlined in Table 3.1, and some examples are shown in Figure 3.8. The severity of these diseases varies both within and between affected families. Keratoderma tends to be more prominent in the weight-bearing areas of plantar skin and can result in discomfort on walking and abnormalities of gait. In addition, patients may complain of malodour as a result of bacterial degradation of the thick keratin layers. Keratoderma which extends to the dorsa of the digits may result in constricting bands and even autoamputation of digits (Fig. 3.9).

Figure 3.8 Patterns of keratoderma: (A) punctate; (B) focal; (C) diffuse. (D) Focal keratoderma is seen with a hypertrophic nail dystrophy in pachyonychia congenita.

Figure 3.9 Vohwinkel’s keratoderma (mutilating keratoderma with deafness). A toe has been lost due to the formation of a constricting band (‘pseudo-ainhum’).

Although thickening of plantar skin is common, features that suggest a keratoderma of genetic origin include: early onset or a positive family history of keratoderma; an extensive or unusual pattern; thickening of the skin of other areas such as the elbows, knees and wrists; and other clinical features such as abnormalities of the hair, nails and teeth or a history of deafness. If an inherited PPK is likely then referral to a dermatologist may be appropriate.

In a few families with an inherited PPK there is an associated increased risk of developing some internal malignancies. In a few families, focal keratoderma is associated with a high risk of oesophageal cancer (the Howel–Evans syndrome).

Treatment

Patients should be advised on the regular use of topical keratolytics such as salicylic acid 5–10% in white soft paraffin or 35–70% propylene glycol. Occlusion with polythene increases the efficacy of keratolytics and can be used in combination with manual paring or abrasion with a pumice stone. Oral vitamin A derived drugs (retinoids) are particularly helpful for some patients but may result in increased pain in affected skin. Surgery has an occasional role for patients with focal keratoderma. Keratoderma may be complicated by dermatophyte fungal infections, and skin scrapings should be sent for mycological culture if this is suspected.

CASE STUDY 3.3 KERATIN MUTATION

A 6-month-old child developed blistering and hyperkeratosis of the feet as she began to weight bear. Her mother was affected by life-long hard skin of the hands and feet. Genetic investigation showed them to have a mutation in keratin 9. This intermediate filament protein is specifically expressed in palmoplantar epidermis, and the mutation causes structural weakness and a hyperkeratotic response.

Acquired keratoderma

Keratoderma climactericum

This disorder occurs predominantly in obese postmenopausal women. It presents with erythema and hyperkeratosis over the weight-bearing areas of the heel and forefoot. Patients are often asymptomatic, although pain on walking can be a problem if there is extensive involvement. The disorder has been described in younger women following oophorectomy, suggesting that reduction in endogenous oestrogens may be important in the aetiology. Treatment with emollients and keratolytics may be of some benefit (Deschamps et al 1986).

Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex’s syndrome)

This is a rare cause of acquired keratoderma that is associated with some internal malignancies. It is more common in men and typically presents with erythema and scaling on the extremities (ears, nose, hands and feet). With time the eruption becomes more generalised and more hyperkeratotic, with keratoderma on the hands and feet. Successful treatment of the underlying malignancy often leads to resolution of the disorder (Bolognia 1995).

Keratoderma and hypothyroidism

Palmar and plantar hyperkeratosis have been reported in association with hypothyroidism. Treatment with thyroxine replacement may result in clinical improvement (Hodak et al 1986).

Blistering disorders

Blistering has many causes, including bacterial or viral infections, insect bites and inflammatory skin disorders. Traumatic blistering of the feet is common and is particularly prevalent in recreational sports, such as hill walking and jogging, which impart recurrent shearing mechanical forces to the plantar skin. Poorly fitting or inappropriate footwear may exacerbate the problem. In addition, there is a group of rare skin disorders that are characterised by blistering as a result of inherited abnormalities in a variety of key structural skin proteins.

EPIDERMOLYSIS BULLOSA: THE INHERITED MECHANOBULLOUS DISORDERS

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) encompasses a spectrum of disorders characterised by skin fragility and blistering following mild mechanical trauma. Recent research into EB has identified the molecular basis for a number of the diseases, opening up the possibility for prenatal diagnosis and gene-targeted therapy in the future.

EB can be broadly divided into three groups of diseases on the basis of the ultrastructural level of the blister formation.

AUTOIMMUNE BLISTERING DISORDERS

Disease mediated by autoantibodies against target antigens in the epidermis or its basement layer results in increased skin fragility or blistering. The commonest autoimmune blistering disorder is bullous pemphigoid, in which proteins of the basement membranes are attacked. This causes the whole epidermis to lift off, producing an intact firm blister. On the feet, the blisters may be more vesicular, resembling those of pompholyx (Fig. 3.11). In the various forms of pemphigus, antibodies are directed against adhesion molecules within the epidermis, and the result is friable blisters or erosions. Both of these conditions are commonest in the elderly, and require aggressive treatment with high doses of oral corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents.

Tumours

‘Tumor’ in Latin simply means a swelling. This, on the foot, could include some corns, verruca plantaris, boils, etc. By usage and wont, the anglified version ‘tumour’ (American ‘tumor’) is applied to new growths or neoplasms (Table 3.2). Customarily, these are divided into benign or malignant, which is obviously a vitally important distinction. In the skin, perhaps more so than other systems, these margins can be indistinct. Some tumours are initially premalignant but inexorably transform if neglected. Some normally benign lesions may become malignant. Some apparently aggressive malignancies may spontaneously involute. Malignancy usually implies the ability to spread, or metastasise, to distant sites by blood or lymphatic vessels. However, lesions such as basal cell carcinoma in the skin may be locally malignant and destructive, but virtually never metastasise.

Table 3.2 Classification of skin tumours

| Tumour type | Degree of malignancy | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Epidermal tumours | Benign | Seborrhoeic keratoses |

| Premalignant | Bowen’s disease | |

| Malignant | ||

| Pigmented skin tumours | Benign | |

| Premalignant | ||

| Malignant | Malignant melanoma | |

| Vascular tumours | Benign | |

| Malignant | Kaposi’s sarcoma | |

| Fibrous tumours | Benign | |

| Malignant | Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans | |

| Adnexal tumours | Benign | Eccrine poroma |

| Other structures | Benign |

Nevertheless, the concept of benign or malignant is a useful working one, provided that the limitations are appreciated and the compartments are not considered too watertight.

Tumours of cells in the epidermis, dermis, appendages, etc. are numerous. Some are very rare. Some virtually never affect the feet. Thus the ones discussed in this section are not exhaustive and selection has been made. Some ‘tumours’, that is swellings, have been included because they might be mistaken for true neoplasms. Some tumours of deeper structures are described, as they may present as a foot swelling.

Any podiatric procedure should include visual and clinical examination of the foot skin and subcutaneous structures (see Ch. 1). The podiatrist is often the person most likely to diagnose foot tumours.

For the patient, ageing, if it brings eyesight problems, obesity and/or arthritis, can make their feet a ‘lost world’. Doctors can be curiously reluctant to examine the feet. Most medical examination couches and their lighting are better geared to visualisation of the upper half of the patient. The daunting prospect of the time involved in the removal of the patient’s tights, multi-laced boots, etc. in a busy surgery can be a deterrent.

CAUSES OF SKIN TUMOURS

The cause of many skin tumours is unknown. Understandably, research has mainly concentrated on malignant tumours. A number of factors have been identified as being important. These include external agents and the host’s genetic makeup.

In 1775, Sir Percival Pott noted an increase in scrotal cancers in chimney sweeps. This was the first realisation of the skin carcinogenicity of soot, pitches and tars. This finding has been confirmed in animal experimentation and in other occupations over the centuries. Other substances, including arsenic, nitrogen mustard and psoralens, have been added. It has been discovered that the agent may have the same property even if taken systemically. This is especially so with arsenic, immunosuppressants, etc.

Areas of long-continued skin damage, such as leg ulcers, burns and tuberculosis infections, may undergo malignant transformation. More recently, the damage due to radiation has been appreciated. Many of the early medical pioneers of x-radiation developed skin tumours, usually on the hands, because they were unaware of the need for protection. A number of skin tumours are linked to excess exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, mainly in the 280–320 nm wavelength range.

Much more recently, the importance of some infecting viruses has been appreciated. A number can produce tumours in animals, either in the natural situation or experimentally. In the human, the papilloma virus (especially types 16/18) promotes malignancy in the female genitalia and cervix. A herpes virus is established in some cases of Kaposi’s sarcoma and a retrovirus in some T-cell lymphomas. This is a developing field and other associations may soon be found.

The host’s resistance depends on genetic individuality, modified by lifestyle, occupation, etc. The Celtic races have skin that tends to burn rather than tan, rendering them more vulnerable to UV-radiation-induced tumours. UV radiation, inter alia, can damage the cellular DNA. Normally, there is a repair system that mops up this damaged DNA. When this is defective, cancer can develop. This happens predominantly in the disease xeroderma pigmentosum, which is rare in the UK but more common in Asia.

Cell growth is a very complicated procedure. Normally genes accelerate it forward at an appropriate speed. If these are altered, they can change to transforming genes or oncogenes (i.e. cancer-producing genes). If viruses are involved they may hijack the normal genes. The oncogenes, formed for whatever reason, may thus inappropriately speed the cells along, proliferating in abnormal forms. The brakes applied in the normal system are via the suppressor genes. Of the tumour suppressor genes involved in human skin cancer, p53 tumour suppressor gene is possibly the most important. When this is inactivated by limitation or inhibition, the brakes fail and the lesion progresses abnormally quickly.

Because of their easy accessibility, skin tumours are easier to investigate than systemic ones. There are bound to be many discoveries in the future.

EPIDERMAL TUMOURS

Seborrhoeic keratosis

Seborrhoeic keratosis (synonyms: senile or seborrhoeic wart, basal cell papilloma) is one of the commonest tumours found. They are benign but can mimic malignant tumours Their incidence increases with advancing age. They tend to cluster on the trunk, but any body surface, including the feet, can be involved. There are several varieties. One type, stucco keratoses, generally affects the legs and ankles.

Clinical features

The commonest type of seborrhoeic keratosis is found on the trunk. There are usually a number of lesions at various stages of development. Initially, they are small papular lesions with a slight increase in pigmentation. They become larger, usually up to about 1 cm in diameter, tending to darken, sometimes until they are almost black. Some can become very large, up to 10 cm or more. The edge is distinct and may slightly overhang the surrounding normal skin. The degree of pigmentation is variable but is usually homogeneous throughout any individual lesion. The surface is rough and wart-like, and at times can become extremely heaped up and thickened. Small circumscribed round areas on the surface are characteristic and known as horn cysts. The surface colour is matt and lacklustre (Fig. 3.12).

Figure 3.12 Seborrhoeic keratosis. Note distinct margin, homogeneous colour and scattered horn cysts.

On palpation they can feel rather greasy – hence the ‘seborrhoeic’ in the name. Horn cysts give them a simultaneous warty feel. On the extremities they tend to be flatter. Some can be irritated by clothing, etc., and secondary infection can supervene.

Some may spontaneously involute, but the natural history is for slow development to a certain size. Normally at least several other lesions can be found. At times, massive numbers can erupt rapidly. This is called the sign of Leser–Trélat. It has been much disputed as to whether this is a sign of underlying malignancy (Lindelöf et al 1992).

Stucco keratosis is the name given to a type usually seen on the legs and ankles. They are usually white or grey and smaller. They rarely exceed 3–4 mm. The crusting is easily detachable.

Seborrhoeic keratoses can usually be easily diagnosed by careful examination, but may be confused with viral warts and other hyperkeratotic lesions. The various pigmented lesions may at times need to be excluded.

Histology

Keratinocytes resembling basal cells gather in the epidermis. Increased numbers of melanocytes may contribute to the darkening colour. Concentric whorls of keratin form the keratin cysts.

Treatment

This is usually indicated for cosmetic reasons or because the lesion is catching and becoming irritated.

Seborrhoeic keratoses are superficial and usually entirely epidermal. They are ideally suited for treatment with liquid nitrogen and usually require only a short application of this. They will curette off easily, and this has the merit of being able to obtain histology, which is always needed if there is diagnostic doubt. The reddish area left will slowly return to normal.

Bowen’s disease

Bowen’s disease (Kossard & Rosen 1992) is an intradermal carcinoma in situ which can slowly progress towards a squamous cell carcinoma. Sun damage, arsenic exposure and papilloma virus have all been suggested as causes.

Clinical features

Bowen’s disease as described in the foreign literature has a predilection for the head and neck but the general view in the UK is of a preponderance to affect the lower leg. The usual picture is of a slowly enlarging reddish, scaly patch with definite margins (Fig. 3.13). This can be mistaken for psoriasis, but a careful history and examination should differentiate. Some of the patches may be more crusted or raised (Fig. 3.14).

Figure 3.14 Bowen’s disease on the dorsum of the foot. Well-demarcated area. Somewhat unusually superadded infection has caused increased crusting.

The differential diagnosis includes basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, malignant melanoma or eczema. If there is doubt, histological examination is essential. Rarely, a nail bed or periungual variant has been described (Sau et al 1994). If neglected, there is a slow progression to squamous cell carcinoma, which is reckoned to occur in approximately 5%.

Basal cell carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma (synonyms: rodent ulcer, basal cell epithelioma) (Leffell & Fitzgerald 1999) is the commonest skin tumour, certainly of the white races. Close on one million occur annually in the USA. They are, however, extremely rare on the foot, and especially the plantar surface, where only about 22 have been described (Roth et al 1995). Even fewer peri- or subungual ones have been noted. A certain number occur on the leg.

Clinical features

The incidence of basal cell carcinoma increases with age. The commonest site is on the face, which may suggest a solar aetiology. However, many occur in areas where there is little or no UV exposure.

The typical history is of a small lesion developing and extending very slowly over months or years. From time to time it crusts and the patient thinks it is healing. The crust comes off with a little bleeding and this cycle often repeats itself, with slow peripheral growth. The outline is round or oval, with a raised or rolled border. This is often pinkish and slightly nodular and is likened to a string of pearls. Over this edge are usually seen dilated telangiectatic vessels (Fig. 3.15). The centre may ulcerate or be more raised and dome-shaped. Locally, they may be very large and destructive, eroding down to the deep structures – hence ‘rodent’ ulcer.

Figure 3.15 Basal cell carcinoma (rodent ulcer). Typical site showing the raised border, like a string of pearls, with telangiectasic vessels crossing it.

Those on the lower leg can be less characteristic (Fig. 3.16), and the differential diagnosis between them and Bowen’s disease, squamous cell carcinoma, malignant melanoma or vascular lesions may be difficult. They virtually never metastasise.

Figure 3.16 Basal cell carcinoma (rodent ulcer) on the leg. Surrounding redness is atypical and due to a contact dermatitis.

Some patients have multiple lesions and some of those suffer from the naevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin’s syndrome). There are several features of this, but with reference to the feet and hands, small pits or depressions may be seen on the plantar and palmar surfaces.

Histology

Cells resembling those of the basal cell layer or appendages appear to ‘bud’ down from that layer. They form spherical masses of very uniform cells in the dermis. Characteristically the cells at the periphery of these spheres line up in a regular arrangement known as pallisading. The masses are surrounded by a fibrous stroma.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (Kwa et al 1992, Salasche et al 1993) arises from the skin keratinocytes. It is the second commonest skin tumour after basal cell carcinoma. It may affect any area of the skin. It is relatively rare on the foot, although an orthopaedic study suggested that, of the soft-tissue tumours encountered, it was the commonest (Ozedmir et al 1997). A rare variant, verrucose carcinoma, largely targets the foot.

Aetiology

Numerous factors leading to squamous cell carcinoma have been described (Kwa et al 1992). The host’s age, natural skin colour, and immune and genetic status are all important. Thus there is an increased incidence of squamous cell carcinoma in those immunosuppressed by drugs or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Similarly, those unable to naturally protect their skin, such as albinos with no pigment or those whose DNA repair mechanisms are impaired, as in xeroderma pigmentosum, are at risk. External agents are also important. Scrotal carcinoma was described in 1775 in chimney sweeps from ingrained soot and tar. Over the ensuing centuries, many other outside factors that may contribute to squamous cell carcinoma have been described. Some skin lesions are known to be premalignant, for example Bowen’s disease (carcinoma in situ) or actinic keratoses. An area of chronic irritation, including leg ulcers, may progress to squamous cell carcinoma (Hill et al 1996).

Human papilloma virus is a powerful carcinogen in genital carcinoma, but its role in the skin is more uncertain (Sasaoka et al 1996). Contamination with tars, heavy mineral oils, hydrocarbons, etc. continues to be a problem in some industries.

Exposure to UV radiation is a definite factor, as witnessed by the problems encountered by fair-skinned immigrants to very sunny climates, as found in Australia, etc. The feet are usually relatively protected, but one variant of squamous cell carcinoma was described in elderly Japanese on the dorsa of unprotected feet (Toyama et al 1995).

X-radiation is also carcinogenic. Repeated damage from radiant heat may provoke erythema ab igne, and rarely may progress to squamous cell carcinoma. Arsenic exposure has been incriminated.

Clinical features

Squamous cell carcinoma may present in very many different ways. Thus, in any unusual or non-responsive skin condition the possibility of it should be borne in mind, otherwise it may be missed.

Figure 3.18 Squamous cell carcinoma on the shin. There is an irregular outline with an undermined edge and a dirty, sloughy base.

The vast majority of squamous cell carcinomas are only locally aggressive, but if neglected, they can spread to the draining lymph nodes and thence to other areas (Lund & Greensboro 1965) (Fig. 3.19). This takes a variable time. Head and neck, genital and large tumours all spread more quickly.

Figure 3.19 Metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma to the groin lymph nodes with subsequent breakdown.

CASE STUDY 3.4 DIAGNOSIS OF ULCERATED AREA

A 70-year-old man presented with a symptomless, irregular, ulcerated area on the dorsum of his left foot. He was of Celtic extraction, but had spent most of his working life as a lifeguard on an Australian beach. What is the likeliest diagnosis and appropriate treatment?

The answer is squamous-cell carcinoma. The Celtic races are more likely to suffer sun damage. The dorsum of the foot is a relatively unusual area, but in his work he is likely to have been more exposed to the sun. It would be essential that a biopsy and surgical excision be undertaken as soon as reasonably possible.

Squamous cell carcinoma variant: verrucose carcinoma of the foot

Verrucose carcinoma (synonyms: epithelioma or carcinoma cuniculatum) (Seehafer et al 1979) may appear at any site but it has a special predilection for the plantar aspect of the foot. Initially it may resemble a simple verruca plantaris. It progresses relatively slowly and may become nodular. At this stage the differential diagnosis would include many nodular foot lesions. With time, the tumour bulk increases and becomes soggy and foul smelling, having been likened to an over-ripe orange. It has a marked tendency to burrow under the skin surface, the sinuses appearing at a slightly distant site from the main lesion – hence the ‘cuniculatum’ denoting a resemblance to rabbit burrows. These rarely metastasise.

Histology

In squamous cell carcinoma the epidermal cells are malignant and manifest in a variety of ways, from large, well-differentiated cells with some individual cell keratinisation, to bizarre, abnormal cells with little or no resemblance to epidermal cells. While in situ, they are contained by the basement membrane to within the epidermis. Sooner or later they ‘break through’ into the dermis, initially often in fine filaments, but later in broad masses.

Verrucose carcinoma is a well-differentiated tumour, but it may have minimal changes suggesting malignancy at the start.

With all suspected squamous cell carcinomas, clinical suspicion should override an apparently normal biopsy. The cancer may not have manifested itself histologically or the sample may have missed the diagnostic part. Therefore, always keep an open mind and be prepared to re-biopsy on several occasions if clinical doubt persists.

Treatment

Prevention should be practised. Measures would include control of UV exposure, radiation, etc. If possible, potentially premalignant lesions should be treated. Particular care in monitoring those at risk for genetic reasons is desirable. This is especially expedient in the immunosuppressed and transplanted patient. Immunisation programmes for young girls in Scotland have commenced. Hopefully, this will reduce the future incidence of genital skin and cervical cancers. The programme may be extended to boys and others later.

In the patient with established squamous cell carcinoma, surgical excision of the region with histological confirmation is therefore the best option. If there is suspicion of lymph node involvement, a suitable dissection should also be undertaken.

In the few patients where surgery is not an option, cryotherapy, laser, photodynamic therapy or intralesional injections have all been suggested. If the patient continues to be at risk, long-term follow-up is necessary.

CASE STUDY 3.5 SEQUELAE OF LONG-TERM VARICOSE ULCERATION

A 58-year-old man asks you about a vascular lesion on his ankle during a podiatry session. He has gross varicose veins with pigmentation around the ankle. He has had a small varicose ulcer near the area for years. He works as a forester. What might be developing?

There are a number of possibilities. Trauma from his work might lead to a pyogenic granuloma. The long-standing ulcer may undergo malignant transformation to a squamous-cell carcinoma. Malignant melanoma on the lower leg may be hypomelanotic or amelanotic. Ideally, histology examination should be undertaken in the near future.

CUTANEOUS METASTATIC DISEASE

Neoplasms beginning in another tissue may spread to the skin by direct extension or as local or distant metastases (Lookingbill et al 1990, Schwartz 1995). These lesions may occur in a patient with known malignant disease or be the first manifestation of the underlying tumour. Skin malignancies themselves, notably melanoma, may also metastasise to other areas of the skin.

Clinical features

There have been several very large surveys of many thousands of patients. Skin involvement as the first sign of cancer is rare (0.8%), and this was equally divided between direct extension, local and remote metastases.

In patients presenting with a tumour elsewhere, skin involvement at that time was found in 1.3%. In all patients with cancers, the skin involvement seems to be of the order of 5%. The skin involvement may come from many initial sites and, in a significant number, no primary site can be identified.

The non-skin tumours that most commonly spread to the skin are breast, colon and rectum, ovary and prostate. There is a wide range of skin lesions. With direct spread from, for example, breast, there may be an apparent nipple or areolar eczema in Paget’s disease, which arises from an intraduct carcinoma (Fig. 3.20). Other breast tumours may spread and grow into the skin, hardening it to resemble a metal breastplate (carcinoma en cuirasse). This may occur in tumours from other sources. Many other types of lesion occur. Small nodules are perhaps the commonest. They often appear to be under the skin, pushing up from below and splaying out the normal cutaneous markings (Fig. 3.21). Indurated erythema, telangiectic plaques or non-healing ulcers are among descriptions of other presentations.

Figure 3.21 Cutaneous nodules pushing up from below. These are secondaries from a primary breast cancer.

When the skin metastasis comes from another skin tumour, malignant melanoma is the commonest cause. The metastases will often mimic the original tumour.

PIGMENTED SKIN LESIONS

Skin colour is largely, although not entirely, due to melanin pigment produced by melanocytes (Bleehen 1998, MacKie 1998, Rhodes 1999). These cells originate from the neural crest and are found in the skin from the eighth fetal week onwards. The melanocytes are the basic factory unit. The rate of production of pigment is influenced by many factors. Ethnic background and sun exposure are two obvious influences.

The melanocyte produces a pigment-containing package – the melanosome – which is transferred to the keratinocyte. The melanocyte is a dendritic cell, which can interdigitate with and ‘service’ about three dozen keratinocytes. This entire complex is called the melanin unit.

The melanocytes are normally situated in the basal epidermal layer and comprise approximately 6% of these cells in covered sites. This rises to 15% in sun-exposed areas.

Naevus

A naevus is the term used to designate a non-malignant growth. Its use is mainly, although not exclusively, confined to skin lesions. They can be classified under headings such as epidermal, dermal, subcutaneous, vascular, etc. Pigmented naevi (in lay terminology, moles) form a large group.

Freckles

Freckles (synonyms: ephelis, ephelide) are common, especially in red-haired persons of Celtic extraction. In size, they are up to 2–3 mm. They tend to be familial. Freckles require UV radiation to develop and usually appear in sun-exposed areas at the age of 3–5 years. Thereafter, they fluctuate in colour intensity in response to sunlight. There is no increase in melanocyte numbers, but these produce more and slightly unusual melanosomes.

Treatment is unnecessary, although these populations are statistically more liable to malignant melanomas. This may be due to them having a similar phenotype and pigmentation profile to adults at risk (McLean & Gallagher 1995).

Lentigo

Lentigos are flat, brownish/black lesions, of which the common ‘age’ or ‘liver’ spots on the dorsa of the hands are examples. They may be induced by sun (solar or actinic changes) but, unlike freckles, tend to fade with UV protection. The lesions can get quite large, up to 25 mm or more and, although the margins can be somewhat ragged, the overall pigmentation is homogeneous with no clumping. They may respond to cryotherapy.

Variants occur in relation to other UV stimuli. Photochemotherapy plus PUVA leads to PUVA lentigos, and sun-bed usage to very large, dark, freckle-like lesions with a slightly irregular edge.

Lentigos show an increase in normal melanocytes, which are arranged along the basal layer.

The sun-bed and PUVA lentigos indicate skin damage and such patients may be at later risk of developing malignant melanoma.

Congenital melanocytic naevus

Congenital melanocytic naevus (synonym: congenital naevomelanocytic naevus) should, by definition, be present at birth, and about 1% of neonates have these. However, rather similar lesions can develop up to a few years postpartum and may be included under this title. It may be that some of these contain the naevus cells, but for whatever reason they delay in producing the pigment. The lesion probably forms between the second and sixth uterine months.

It is traditional to classify these naevi according to size: under 1.5 cm is small, 1.5 cm to 20 cm is medium, and over 20 cm is large.

Clinical features

Congenital melanocytic naevi are usually brown to black in colour. The skin markings can be seen traversing the lesion and may be more pronounced than normal. In many cases, hair of an inappropriate terminal type will develop with time. The surface of the lesion may be smooth, ranging to warty or lobular. An irregular edge may cause concern, but the pigmentation in this area, and throughout the main lesion, is relatively homogeneous. They grow disproportionately slowly with age, compared with the increase in body size (Fig. 3.22).

Histology

Melanocytes are increased in the basal cell area. There is often a gap with a relatively normal area and clumps of naevoid melanocytes in the lower dermis. These seem to have a predilection for skin appendages.

Treatment

The true incidence of congenital melanocytic naevi developing malignancy is disputed, but it is generally agreed that the larger they are the more likely is this complication. However, the large congenital melanocytic naevi affecting the extremities seem to be immune from this (DeDavid et al 1997). Nonetheless, monitoring of all these lesions is advised. Serial photography is advocated.

Small lesions may be excised for cosmetic reasons. The larger the lesion, the more disfiguring it is, but perversely, the more difficult it is to remove. Regular monitoring and attempts at cosmetic camouflage are perhaps the best options.

Acquired melanocytic naevus

An acquired melanocytic naevus (synonym: acquired naevocytic naevus) is an abnormality, but it is an abnormal person who never has any of these. They affect both sexes and appear at intervals throughout life, from shortly after birth. Small numbers present, peaking in incidence around the teens, then falling off in old age.

The melanocytic naevus cells have been the subject of long debate as to their origin. They may be entirely located at the dermoepidermal junction forming junctional naevi. Junctional naevi may represent a stage in the development of compound naevi. This progression is often arrested in areas such as the palms, soles and genitalia, where they can remain for a long time. If junctional changes persist and dermal ones develop, the lesions are called ‘compound naevi’, of which there are various histological variants. There may be closely packed melanocytic naevus cells in the dermis, mainly in the upper papillary layers, in contradistinction to the appearance in congenital naevi.

If the junctional changes are absent, the lesion is termed an ‘intradermal naevus’.

Clinical features

Acquired melanocytic naevi occur in both sexes, with an increased prevalence in black skin (Fig. 3.23). Junctional naevi are the commonest on palms, soles and genitalia. They are usually flat and only a few millimetres in diameter, being round or oval. The colour varies from brown to dark black. Occasionally, stippling can be seen, often with the aid of magnification. The individual, darker areas have a smooth outline. The skin markings are not disturbed. With time, in areas other than the palms and soles, etc., they usually progress toward compound naevi.

Figure 3.23 Typical benign acquired naevi. They are multiple with a clearly demarcated edge and the colour is homogeneous.

Compound naevi are usually dome-shaped papules with a light to dark colour, which is usually homogeneous. Coarse hair may grow through the lesion. Occasionally, there can be a circle of increased pigmentation around the periphery, which may be postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from trauma. The nail matrix may be affected by junctional or compound naevi, with a marked preponderance of the former. Longitudinal melanonychia may occur (Tosti et al 1996).

CASE STUDY 3.6 POSSIBLE MELANOCYTIC NAEVUS

A 20-year-old woman noted a brown spot on her right sole. It measured about 2 mm in diameter. She was reasonably sure that it had not been there 4 months ago. She was on the oral contraceptive. On examination, the pigmentation was homogeneous, the margin was distinct, the lesion round and the skin markings uninterrupted. What should you do?

The answer is to reassure her. The history and examination suggest a benign acquired melanocytic naevus. In view of the apparently fairly rapid history, she should be reviewed in a few months to see if any change has occurred. The oral contraceptive pill is not relevant.

Intradermal naevi

With the disappearance of the junctional component, pigmentation tends to fade. In intradermal naevi, the lesion is often a flesh-coloured papule. Hair may grow through it (Fig. 3.24).

Histology

In the junctional naevus, small collections of melanocytes or ‘packets’ seem almost to be inserted between the epidermis and dermis. Thereafter, some appear to travel into the upper dermis, either as packets or columns. This forms the compound naevus. When the junctional activity fades, the lesion becomes an intradermal naevus. There is often a zone of normal dermis between the lesion and the epidermis.

The melanocytic naevus cells have nuclei of similar size to normal melanocytes. They have abundant, slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm. There are many histological variants.

Treatment

It is manifestly impossible to remove all naevi and, indeed, this would be undesirable. Surgical removal can be carried out for cosmetic reasons or if the physical location is such that constant irritation occurs. The patient must be aware that formal surgical excision will inevitably result in a scar. This scar may be more noticeable and disfiguring than the original lesion. This is particularly so in the young teenager or adult, with firm elastic skin. It is especially relevant to lesions on the trunk, and in particular on the back.

Some of the protuberant lesions may be improved by a shave biopsy. This will not remove any hair growth and, if there is deeper pigmentation, it may recur and darken. That the lesion will not regrow cannot be guaranteed.

Acceptance of the lesion as a ‘beauty spot’ or cosmetic camouflage techniques are other options.

If there is any doubt whatsoever that the lesion may be a malignant melanoma, excision, or at least a diagnostic biopsy, should be carried out. If there is less doubt and these procedures are deemed to be liable to be mutilating, then assiduous monitoring is essential.

Speckled and lentiginous naevus

Speckled and lentiginous naevus (synonym: naevus spilus) (Rhodes 1999, Stewart et al 1978) is considered relatively rare, although an Australian survey found a prevalence of 2% (Rivers et al 1995). Originally called naevus spilus (from spilus = dot), this name has become confused in the literature, especially when tardus (i.e. late developing) is added as naevus spilus tardus. Some reckon this to be equal to Becker’s naevus.

Clinical features

The lesion usually develops in childhood on the extremities, but other areas can be affected. It is a light brown macular area that may measure up to 10 cm in diameter. Spots, which may be very dark, develop within this (Fig. 3.25).

Histology

The macular area has increased melanocytes, like a lentigo, and the dark areas show melanocytic naevoid cells in the epidermis and dermis.

Becker’s naevus

Becker’s naevus (Monckton et al 1965, Vincent 1999) is a fairly common lesion, occurring in about 1 in 2000 young men and a fifth of that in females. It is pigmented, but there are few or no changes in the melanocytes.

Clinical features

It usually appears in the late teens or early adult life, gradually becoming more obvious. The usual site to be involved is the shoulder, but other areas, including the leg, have been described.

It is often large in area (over 20 cm diameter) with a markedly indented geographic outline. Within it, there can be white island areas about the size of a fingertip. Normally, coarse, darkish hairs develop within the patch. They remain for life.

Spitz naevus

Spitz naevus (Casso et al 1992) is a benign melanocytic lesion, akin to a compound naevus. However, the histology can be very similar to that of malignant melanoma, and pathologists asked to look at it without an adequate history can be forgiven for diagnosing the latter. In the past, benign juvenile melanoma was used to describe these naevi, but it is a term best not used, to avoid confusion.

Clinical features

Spitz naevi usually occur in young people up to the age of 20 years. The head, neck and leg are common locations, although anywhere may be affected. They are usually asymptomatic, dome-shaped, firm nodules, which are pink, red or tan in colour (Fig. 3.26). The natural history is unclear.

Dysplastic naevi

Synonym: clinically atypical naevus. Some patients have naevi, often multiple, which exhibit clinical and/or histological features that are unusual and worrying (Sagebiel 1989, Slade et al 1995). These can occur in some families or in isolation. Many different names have been applied to these. They prove a difficult management problem.

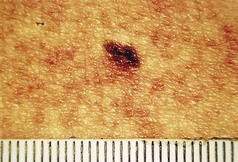

Clinical features

By definition, these are clinically atypical lesions and thus the great concern is to try to differentiate them from malignant melanoma. It is difficult to convey a word picture. They may occur in any sites, either singly or sometimes in vast numbers. They tend to be larger than benign naevi, often more than 5 mm in diameter. They are roughly round or oval, with some asymmetry. The border is irregular, but often fuzzy, rather than sharper, larger projections of the malignant melanoma. There may be a collarette of increased pigmentation. Colour variegation within the lesion is common, but more ‘twin tone’ in contradistinction to the multiple variations seen in malignant melanoma (Fig. 3.27).

Figure 3.27 Dysplastic naevus. This shows the difficulty in distinguishing this lesion from a malignant melanoma. The borders and colour heterogeneity are not so marked as in malignant melanoma. If in any doubt, further investigation or excision is necessary.

The actual areas of pigmentation have more regular edges. Skin markings are usually uninterrupted.

The natural history is difficult to assess. Some may disappear, but all in all there is an increased chance of melanoma developing, which may be up to 70 times (Halpern et al 1993). This is most marked in those with multiple lesions and a family history of malignant melanoma.

Histology

The microscopic changes may be found with or without clinical atypia and may be reported by the pathologist as dysplastic. As with the clinical situation, there is a kaleidoscope of variation within the histology. The cardinal changes are an irregular proliferation of melanocytes, singly or in packets along the basal cell layer. There is elongation of the rete ridges. The melanocytes themselves show variable atypia.

Treatment

Any dysplastic naevi that cause clinical concern should be excised, along the same lines as for malignant melanoma. If there is less concern, then they may be left. If they are multiple and there is a family history of malignant melanoma, regular careful supervision is required. General photographic views plus individual close-ups are invaluable.

Malignant melanoma of the skin

A cutaneous malignant melanoma (Grin-Jorgensen et al 1991, Langley et al 1999, MacKie 1998) arises from melanocytes in the epidermis. Similar tumours may occur in other tissues (e.g. the eye). It is vitally important for the patient and/or practitioner to diagnose the melanoma early, when a cure can easily be effected. Missing it until it is in later stages will greatly increase the chances that it will lead to the patient’s death. There has been a tremendous increase in the incidence of the tumour in the last 50–60 years. It has been reckoned that in the USA the individual risk of an invasive melanoma increased from 1 in 1500 in 1935 to 1 in 75 in 2000.

Aetiology

The main causative factor for malignant melanoma seems to be sun exposure, although some still seem less convinced. A single or a few burning episodes in the child or the young adult seems to be more provocative than longer term outdoor unprotected activity. Thus the culture in the western world of sun tanning by natural or artificial means, more holidays in the sun and scantier clothing may all play a part.

Some people are more at risk than others. The red-headed, freckled, Celtic races are a particular example. They tend to burn in the sun easily and their voluntary or enforced migration to sunnier climates has been responsible for an ‘epidemic’ of malignant melanoma in, for example, Australia.

There are differences in incidence in different occupations and socio-economic groups. Some of these may be dependent upon affordability of holidays, outdoor exposed working, etc.

In a few cases there is an apparent hereditary tendency to develop malignant melanoma. Skin type, lifestyle, geographical domicile, etc. all influence this.

There was an initial marked increase in malignant melanoma in females compared with males, although the incidence is now rising disproportionately in the latter. Differences in dress patterns may have been important.

Patients with some pre-existing pigmented lesions are at more risk of malignant melanoma. These include some dysplastic naevi and acral pigmented lesions. A personal history of a previous malignant melanoma renders the patient more at risk of developing a second primary lesion.

Clinical features

Some malignant melanomas produce little or no pigment and are termed hypomelanotic or amelanotic melanomas. They pose particular difficulties in diagnosis. Most, however, retain the facility of pigment production. A careful history and meticulous examination in good light are essential. A changing lesion should be paid particular attention. There are many devices marketed to help visualisation, some of which are very expensive. Much can be achieved with a spotlight and some magnification, even using a hand lens. In most medical locations an auroscope is available and, used without the ear piece, this gives light and some magnification. Sometimes the application to the surface of the lesion of a little mineral oil will alter the refraction and allow the clinician to see a little deeper into the epidermis. Appearances on plantar surfaces may be misleading (Akasu & Sugiyama 1996).

Features that would cause concern in the pigmented cutaneous malignant melanoma are mainly related to irregularity. This irregularity of the outline, the border and its pigmentation, colour of the lesion and the skin marking are all ominous features. Increasing size to more than a pencil thickness (i.e. about 7 mm), bleeding, discharging and itching, can all be added.

An ABCD checklist has been suggested:

It must be stressed that no system will be foolproof in the diagnosis of malignant melanoma. Very early lesions will not have developed the above features. A practitioner must realise that an evolving lesion may not be diagnosable at that moment in time, and the patient should not be deterred from seeking further advice if the lesion appears to change.

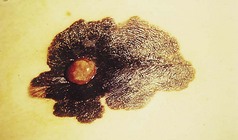

The prognosis depends vitally on the thickness of the melanoma. Those with a horizontal growth pattern are termed ‘superficial spreading melanomas’ and have a reasonably good outlook in general. On the other hand, those that grow vertically spread more rapidly into the lymphatics and blood vessels, metastasising earlier, with a consequently poorer prognosis. These are termed ‘nodular melanomas’.

These and some other clinical types of malignant melanoma are recognised.

Figure 3.29 Malignant melanoma. This exhibits asymmetry, an irregular border and colour variation. The main lesion is in a superficial spreading phase but the nodule represents vertical growth.

Figure 3.30 Malignant melanoma on the left with irregularities of border and pigmentation. The serendipitous juxtaposition of a seborrhoeic keratosis on the right allows a comparison of features.

Figure 3.31 Malignant melanoma on the ankle of a 21-year-old female. Jagged irregular border. over half of the lesion is almost amelanotic.

Figure 3.34 Neglected subungual malignant melanoma. Hypomelanotic. Only a small rim of pigmentation can be seen.

Malignant melanoma can be an enigmatic and unpredictable disease. Very early lesions may spread. Nonetheless, there is usually a close correlation to the thickness of the tumour. The deeper the lesion penetrates the more liable it is to spread.

Metastases may take the form of nearby local nodules or spread to the local lymph nodes. Distant areas of skin, subcutaneous tissue and nodes may be affected. The visceral metastases affect, in descending frequency, the lungs, liver, brain, bone and intestines. All of these may occur many years after apparent cure.

Malignant melanoma may present as a distant metastasis. Sometimes the initial primary cannot be found. This may be due to the fact that, rarely, primary melanoma can spontaneously heal.

In the examination of patients with pigmented lesions in general and malignant melanoma in particular, the keeping of meticulous records is mandatory. The history of the patient’s observations and symptoms, a family history and a lifestyle for risk factors should be taken. On examination, measurements of the horizontal and vertical sizes, comments about the border, irregularity and colour variegation should be noted. If possible, the regional lymph nodes should be palpated.

Histology should be obtained if there is the slightest doubt about a lesion. There has been much controversy as to whether an incisional biopsy is likely to provoke spread and, to a certain extent, this still continues. Many authorities feel that there is no evidence for this. If possible, an excisional biopsy should be done, but there may be occasions when it is more expedient to send a part for diagnosis. Some feel that in thicker melanomas a biopsy of the main draining (sentinel) lymph node should be done. This can be identified by dye or radiation methods. This approach still remains controversial (Garcia & Poletti 2007).

CASE STUDY 3.7 AREAS OF PIGMENTATION

A 40-year-old labourer notices a brown subungual area on his right, second toe. He cannot remember any specific injury. On examination, a band of pigmentation is seen, extending throughout the length of the nail and onto the posterior nail cuticle. What action would you take?

The history and examination are highly suggestive of a subungual melanoma, and immediate fast-track referral for surgery is imperative.

Histology

Malignant melanocytic cells invade the dermis. The cells vary in the degree of atypia, with cellular and nuclear enlargement and variation. There is often upward spread into other areas.

Stress has been placed on the importance of the thickness of the malignant melanoma, and the pathologist has a vital role to play in the measurable assessment of this. Originally, this was done by measuring the invasion of the tumour in relation to other anatomical structures of the dermis. These were known as Clark’s levels I–V:

However, this can be difficult on certain sites, such as acral ones, and a micrometer measurement known as the Breslow thickness is now more often used. Using this, melanomas under 0.75 mm are considered to have a good prognosis. Over that, the outlook steadily declines with increasing thickness.

Treatment

Prevention by removing all removable known causes is desirable. There have been many campaigns to warn of the dangers of sun exposure and to promote methods of sun protection. These need to continue.

Persons at risk from genetic problems, past history or due to at-risk pigmented lesions require careful monitoring.

In the suspected malignant melanoma, fast-track referring is essential.

In the event of malignant melanoma being diagnosed clinically or histologically, rapid and adequate excision at the primary site is of paramount importance. The exact surgical clearance margins are disputed but, in general, the thicker the lesion, the wider should be the margins.

If the regional lymph nodes are involved they should be excised.

Once the tumour has spread further, the prognosis is dire. Much work continues on the best chemotherapeutic regimen.

Epidermal naevi

These are a collection of hamartomas or benign abnormalities. They are present from birth, but may not be clinically recognisable until later. Various classifications are suggested. Many lesions do not conform to these headings. Many are warty.

Clinical features

Appearing at or after birth, the lesions develop slowly. Many are linear, probably along the path of embryonic development lines (Blaschko’s lines).

Usually the surface becomes warty and pigmented, especially so on the limbs and palms and soles (Fig. 3.35).

Some become inflamed and intensely itchy. These may be designated inflammatory linear verrucose epidermal naevi (ILVEN).

Dermal and subcutaneous naevi

Hamartomas may affect any of the dermal or subcutaneous structures. They may be isolated lesions or part of a syndrome (e.g. the tuberose sclerosis complex). Classification of dermal and subcutaneous naevi can be difficult, and infinite variations occur.

Usually they present clinically as a swelling. Often the diagnosis is obtained from the histology.

VASCULAR TUMOURS

Pyogenic granuloma

Pyogenic granuloma (synonyms: granuloma pyogenicum, lobular capillary haemangioma) is a common lesion that usually follows an injury, which may or may not be remembered by the patient. In a paediatric survey, most gave no history of trauma (Patrice et al 1991). The injury may rarely be iatrogenic (e.g. after cryotherapy) (Kolbusz & O’Donoghue 1991).

Clinical features

A friable vascular lesion develops rapidly at the site of a previous injury, or apparently spontaneously. There are, rarely, generalised forms of the disease that cannot be due to trauma and occasionally may have an underlying malignancy (Strohal et al 1991). Multiple ones may be triggered in severe acne on the site of active lesions where treatment is inaugurated with retinoids (Exner et al 1983). Paronychia has been described as a cause (Bouscarat et al 1998).

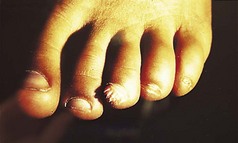

However, the commonest form is a single one. A usual history is of a thorn or pinprick injury followed by the development of a mushroom-type lesion, which bleeds on the slightest touch. Because of this, it is common to see evidence that the patient has covered the lesion with a protective dressing (Figs 3.36, 3.37).

Lesions occurring in restricted anatomical sites are constrained and may lose their mushroom-like appearance. An example of this would be in a nail fold (Fig. 3.38).

The lesion reaches a variable size, usually up to 1 cm, and then ceases growing. In long-established pyogenic granulomas there may be an attempt at epithelialisation, which may lessen the tendency to bleed. Some spontaneously involute. Some develop surrounding or satellite lesions of more pyogenic granulomas locally.

Pyogenic granuloma is usually an easy diagnosis to make and usually responds to treatment. However, it is vital not to miss a more sinister diagnosis, which some tumours may mimic. The greatest pitfall is the malignant melanoma, especially amelanotic or hypomelanotic ones (Elmets and Ceilley 1980).

Other tumours, such as Bowen’s disease or squamous cell carcinoma (Mikhail 1985), verrucose carcinoma (Brownstein & Shapiro 1976), eccrine poroma (Pernia et al 1993) and metastatic lesions may confuse (Giardina et al 1996). Never remove tissue without first obtaining histological confirmation.

Histology

The lesion is circumscribed and contains multiple capillaries, some very dilated (Lever & Schaumberg-Leuer 1990). There is considerable proliferation of endothelial cells. At the base, the epidermis tends to grow, leading to a collarette constricting the lesion and contributing to the ‘mushroom stalk’.

Treatment

The pyogenic granuloma is usually easy to curette. The tissue obtained should always be sent for histological examination. Curettage may need to be repeated on one or two occasions. Formal excision can be carried out.

CASE STUDY 3.8 FRIABLE NODULES