Chapter 1 Examination and diagnosis in clinical management

Associated manifestations of symptoms

Factors that aggravate or relieve symptoms

MRC classification of muscle power

Quantity or severity of symptoms

Signs and symptoms of peripheral vascular disease

‘Use the past as a mirror when studying the present; there can be no present without the past.’

‘Watching others do something is easy; learning to do it yourself is hard.’

’To experience is better than to be told; seeing for oneself is better than hearing from others.’

Chinese proverbs (Wanheng & Xiaoxiang 1996)

INTRODUCTION

Communications are the most useful/vital component part of clinicians’ skills, allowing them to manage patients effectively and efficiently. It is apparent that, in a litigious society, failure to communicate to, with and about our patients is a primary cause of many cases against practitioners. It is failure to communicate with the patient from the start, in our history taking, that may lead to misdiagnoses, poor management strategy or poor compliance by the patient. Failure to communicate properly what occurred during the consultation phase, and to document the management strategy and agreement by the patient in the case record leads to many cases of complaint, disciplinary procedures or litigation by patients against podiatrists.

The process by which clinicians gain, analyse or interpret the information that the patient imparts to them is, by and large, an invisible process, but it gives visible and resultant shape to the data compiled throughout the consultation and clinical interactions. ‘Clinical thinking’ is a name given to that invisible process (Bates 1995). It is a process demonstrated and observed during training but developed and honed by experience and continuous professional development of clinical and academic skills. It is a skill that is acquired rather than taught, as it is very much based on clinical experience and judgement.

GATHERING DATA

From the initial referral letter, or initial contact with the patient in the surgery, the practitioner continually observes, asks open-ended questions and uses additional methods to encourage the patient to divulge his or her story.

This process of taking a podiatric history comprises many constituent parts and in American terms is the ‘clerking process’. To many students it is a daunting experience, requiring the collection of information, which often needs restructuring to make sense of the vast amount of data obtained from both the history and the examination. The student/practitioner requires an open, enquiring approach to this process, within a systematic framework, to ensure that the all-important information is gleaned in an efficient and effective manner.

During the process the student/practitioner needs to encourage the patient to divulge information. This encouragement may take numerous forms (Bates 1995):

The interview/consultation is potentially the most powerful, sensitive instrument at the command of the podiatrist, and yet it is probably the most misused or misunderstood aspect of our practice.

The patient has become the focus of NHS attention, and as patient-based clinical methods are paramount, the interview/consultation has taken on even greater importance. Most clinicians still rely on the gathering of information from the patient as the prime means of making a diagnosis and deciding on a management strategy for treating the condition or complaint. Technology and instrumentation or tests assist in the process but communication is still the primary basis of the process. The physical examination is based on the information gleaned, and helps to confirm an initial working hypothesis or diagnosis and to enable the clinician to make the best use of resources such as tests, diagnostic equipment, time and expertise. It also demonstrates a professional approach to the patient, and is both an efficient and an effective use of scarce resources.

It is routine practice that a patient’s history is obtained before undertaking a physical examination. Remember, however, that informed consent is required for a practitioner to obtain information and prior to performing a physical examination. It is prudent to ask the patient whether he or she is willing to divulge information to you by explaining why and how the consultation will be conducted.

After the physical examination it may be necessary to conduct a further specific examination or to undertake more robust tests, or to refer elsewhere for further opinion. Although these are explained as separate areas, they should be viewed as dynamic intertwined processes. Taking the history is usually the first, and perhaps most important, aspect of the assessment of and interaction with a patient. It is a gathering of data that is not just about the specific complaint that brought the patient to the surgery and upon which the podiatrist will make the diagnosis. It is a learning experience for the practitioner about the patient, about how the patient experiences and views his or her symptoms, and perhaps about the patient’s expectations of treatment. It also allows the patient to have a learning experience about the practitioner. Thus it is the building block or foundation of future trust and a professional patient–practitioner relationship.

TAKING A COMPREHENSIVE PODIATRIC HISTORY

The purpose of a consultation is twofold.

First, it allows the patient to present the problem to the podiatrist, which is a therapeutic process in itself.

Secondly, it enables the podiatrist to sort out the nature of the problem (diagnosis) and decide on any further course of action that might be needed.

There are four key skills to history taking:

The manner in which a podiatrist talks with, rather than to, a patient while taking the history, establishes the foundation for good care. Listen carefully; respond skilfully and empathetically (Bates 1995) – the active listening stage. The podiatrist needs to learn what exactly is bothering the patient, what symptoms he or she has experienced, and what the patient thinks the trouble may be, how or why it happened and what the hoped-for outcome is. As the information is given, the podiatrist formulates hypotheses or a range of potential diagnoses. Do not attempt to plump for a diagnosis straight off, as this may close the mind to other signs and symptoms that do not fit with that hypothesis. The hypothesis/examination, or history taking, starts immediately the patient is introduced in the waiting room and the practitioner greets the patient. Too often practitioners miss the opportunity to observe patients unobtrusively while they are relaxed and apparently unobserved – from the time they are called to the time when the patient feels the consultation starts (i.e. when they are sitting on the patient’s chair). Significant opportunities for gait analysis are missed. The standard approach is to elicit the history before any physical examination (Marsh 1999) but this misses opportunities to observe patients in the waiting area without them knowing they are being observed.

The atmosphere and setting of the assessment is as important as the examination itself. The patient should be assured of absolute confidentiality, and the assessment should not be rushed. Each patient expects, and deserves, full attention to and sympathy for their problems. The patient should feel confident in the podiatrist’s diagnostic abilities, but also in their empathy, understanding and motivation. ‘The history is the most important part of the patient’s assessment as it provides 80% of the information required to make a diagnosis’ (Marsh 1999).

Assessment forms the basis for any planned intervention (Baker 1991), providing the baseline upon which subsequent intervention is measured and outcomes compared. Systematic, ongoing assessment is vital, to monitor and evaluate the success of care and detect new or different problems from those presented initially. This forms the basis of evidence-based practice and care. However, prior to any form of assessment, the patient’s consent to treatment and giving of personal information should be sought.

There are two types of consent: tacit and informed consent. Consent is defined as ‘to give assent or permission; accede; agree. It is voluntary acceptance of what is planned or done by another, agreement as to opinion or course of action’ (Readers Digest 1987). Tacit consent is the act of non-verbal or written agreement to treatment, while informed consent is the act of making a rational consent to treatment based on all the facts provided (Ricketts 1999). If a patient agrees to come to the podiatrist’s surgery, removes their socks and shoes, and sits in the chair expecting treatment, they are tacitly agreeing to the podiatrist undertaking some form of examination. However, when a specific form of treatment/examination is proposed, informed consent is required from the patient to ensure their compliance with and agreement to that form of treatment/examination taking place. Again, this comes down to communication. Patients should be aware of why a podiatrist requires certain information, such as current medication, previous illness, previous drug therapy, surgery etc., otherwise the patient may not see the relevance and not divulge the information – potentially leading to misdiagnoses as a consequence of the incomplete information upon which the diagnosis is based. The podiatrist cannot do every possible test on every patient, and therefore intelligent use of the history may shorten the examination and yet make it more informative (DeMeyer 1998).

ELEMENTS OF THE HISTORY

The examination will consist of:

Introductory information

Introductory information includes the date of the history taking, identifying data or demographics (age, sex, ethnicity, place of birth, marital status, occupation, religion), source of referral (if any), source and reliability of the history. The history taking then proceeds to a discussion of the patient’s chief complaints. It is necessary to discuss with the patient why these particular pieces of information are required, especially as nowadays people are more attuned to discrimination for various reasons. Careful thought should be given as to why these pieces of information are really needed. Age can lead to vital clues as to which condition it is most likely to be, given that some foot pathologies are more likely to occur in early childhood, but the effects may produce other pathologies in later life. Furthermore, women are more at risk of some disorders than others; for example, rheumatoid disease is three times more likely in women than in men at a given age. The patient’s place of birth may lead to a diagnosis of a rarer form of systemic disease than would otherwise be suggested by the current place of residence; for example, someone now resident in the UK, but who was born and spent most of their early childhood in the Indian subcontinent, may have developed Hansen’s disease – a condition not normally associated with the UK. Marital status may provide assurance that the correct phrases and forms of address are used, and that no faux pas are made by the podiatrist leading to a breakdown in communications, for example, where children are concerned. Occupation is possibly the most easily explained question, as it may give vital clues to the amount of load or trauma the foot is undergoing, or specific conditions to which the foot is exposed. Religion, perhaps, will help to guide practitioners through some areas leading to non-compliance with management plans, or the inability of the person to communicate certain vital clues to diagnoses. Communication skills are required throughout, ensuring tact, diplomacy and empathy.

Chief complaints – soliciting contribution

This is the main focus of the history and the prime reason why the patient has presented to the practitioner. A detailed and thorough investigation of the current concern is vital, and comprises two essential but combined parts: the patient’s account of the symptoms (ensure that it is the patient’s view and not that of another, such as a carer or parent), that is the subjective symptoms; and the objective signs – those detected by the skill of the practitioner. The main aim is to obtain a comprehensive, succinct account of the patient’s perspective of the presenting symptom(s). There is a need to allow patients sufficient opportunity to describe their symptoms for themselves. The practitioner needs to practise patience and take care not to interrupt inappropriately. If the patient starts to drift, that is the time to interrupt and take control of the situation. Ask specific questions to obtain detail – the interrogative stage of the history taking. If the history is complicated, reflect on the information and recount it back to the patient, to ensure that he or she agrees with your interpretation. Attempt to be systematic and objective. Look for other supporting evidence to the interpretation, ensuring that questions are posed in a simple, unambiguous manner, without technical or medical jargon.

Past medical history

This includes information about the patient’s general state of health, childhood illnesses (remember the age of the patient and his or her country of birth), adult illnesses, psychiatric illness, accidents and injuries, and operations and hospitalisations. This information will help you gauge the patient overall, and how he or she views health and disease. It is also important to gain outline information of what investigations have been made during previous hospital admissions or at clinics, so reducing duplication of effort. Procedures or operations should be listed chronologically to help with future additions – they should be collected and reported with dates where possible. There is the need to pursue problems that are related to the underlying present condition or complaint.

Drug/medication history

It is advisable to request this information before the first appointment by advising the patient to present with a list of current medication (prescribed and over-the-counter medicine) and dosage. The drug history may give an indication of current illness. It is important to include home remedies, vitamin/mineral supplements, borrowed medicines, as well as prescription-only medicines (POMs) and over-the-counter (OTC) drugs. The drugs may be the cause of the symptoms (some cases of peripheral neuropathy may be induced by drug therapy), or the withdrawal of a drug therapy may be the reason why symptoms are now apparent (e.g. if the patient has suddenly stopped taking diuretics and suffers from swollen and painful ankles). Details should be obtained about possible drug allergies, to inform any decision about the continuation of a drug therapy. Also ask about other allergies such as hay fever, eczema, asthma, or to latex.

Social history

It is important to establish how the disease or complaint and patient interact at a functional level. Try to establish what the patient’s normal daily activities are and how his or her complaint has affected them. Smoking and alcohol consumption are the factors most frequently asked about in this regard, but it is essential that judgements are not implied by the manner in which the questions are asked. It is more difficult but equally important that the use of other related substances is also investigated.

Family history

Information about the health and age of other family members can be useful, particularly where there may be a genetic link to disorders. It may be appropriate to identify age or cause of death of family members such as parents or grandparents.

Review of systems

ATTRIBUTES OF SYMPTOMS

Patients may complain of symptoms that are local (e.g. to the foot or toe) or general (e.g. abnormal gait or more widespread aches and pains). Specific detailed questions by the practitioner can elicit the signs of the complaint. This should be a clear, chronological narrative which includes the onset of the problem, the setting in which it manifests, the means by which it presents, and any treatment that has been tried. The principal symptoms should be described using seven basic attributes (Bates 1995):

The amount of time spent on each component depends on a number of factors: the communication skills of the patient, underlying problem(s) and the listening skills of the practitioner. It is difficult to know when to interrupt and when to allow the patient to continue before stepping in and asking probing closed questions. It is essential, however, that the full circumstances of the presenting complaint are obtained.

Once the various symptoms have been described, it is good practice to undertake a brief review of the symptoms (Marsh 1999) using a systems enquiry method. This may help to arrange the thoughts of the practitioner, highlight missing information, or give guidance as to how to perform the physical examination in a logical sequence of actions. It is basically a screening method for establishing the areas that require detailed physical examination. When the presenting complaint appears to involve only one system, that system is promoted in importance in the examination and a detailed history of the presenting complaint and a more detailed physical examination of that system are made.

PERFORMING THE PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

How complete should a physical examination of a patient be? This is a common question raised by students as well as experienced practitioners. There is growing concern over how much should be assessed and, therefore, how much should be recorded. There is a growing number of pieces of equipment that many podiatrists are starting to use for routine measurements within their practice. However, concern must be raised about the apparent overreliance on sophisticated equipment, which may have a place in some specialist settings but which, on the whole, is too expensive to become necessary in all clinics. Clinicians should rely first on the physical signs and symptoms to indicate whether a more detailed or rigorous assessment is required, and thereafter refer the patient for the specialist tests, or carry these out themselves at another time. In the majority of cases the simple routine consultation, which consists of physical examination together with the ability to use the assessment tools that we all have (i.e. use of the eyes, ears, hands, nose and common sense), should be sufficient. If more sophisticated equipment is to be used, then practitioners require adequate training not only in the use of the equipment but also in the interpretation of the findings. Doppler ultrasound, which enables the sounds of the foot pulses to be identified and recorded, is becoming a routine practice. However, in untrained hands, this equipment can be used incorrectly and diagnoses may be either wrongly interpreted or missed altogether. The equipment may make podiatrists look more professional and more sophisticated. However, the ability to use the equipment correctly, interpret the results accurately and record clearly is something that should be taken seriously.

Therefore, the answer to the question as to how complete an examination should be depends on the signs and symptoms at presentation. The examination and assessment should be related exclusively to the complaint the patient presents with, unless it is thought that a complete and full examination is required to exclude or include other signs and symptoms noticed during the question phase of the assessment process. For patients who have symptoms related to a specific body part (or foot region), a more limited examination may be more appropriate (Bates 1995).

It is the duty of the practitioner to select the relevant methods to assess the problems as precisely and efficiently as possible. The symptoms, along with the demographic data (age, sex, occupation and previous history) collected, influence that selection and determine what examination is required. Knowledge of disease patterns, and the practitioner’s previous knowledge and experience of other conditions also influence the decision. These are all component parts of the clinical thinking, or reasoning, process. When undertaking the physical examination, a sequence that maximises the practitioner’s efficiency while minimising the patient’s efforts, yet allows thoroughness by the practitioner, is the best. Two important details need to be considered: the positioning and the exposure of the patient.

‘Ideally, the whole limb being examined ought to be exposed, but in practice it is usually sufficient only to expose the leg from above the knee distally.’ (Anderson & Black 1997)

This level of exposure should give the practitioner sufficient sight of the main areas of complaint, without requiring exposure that the patient might feel is not justified for a podiatric examination. It is important to be able to palpate and see the knee during the examination, whether the patient is seated or standing (weight bearing). Thus, where possible, trousers should be rolled up to expose the full knee and patella. It is also important that both legs and knees are visible, even when the patient is complaining of problems in only one foot. Comparison, one with the other, is a vital source of data gathering. In most cases patients are examined in a semi-supine position and are positioned at a higher level than the practitioner. However, where a more accurate biomechanical examination is required, the prone or supine position may be adopted. Whatever the position, it should not be uncomfortable for the patient for the duration of that examination. The patient must be able to be relaxed in the position chosen or false data may be gathered. According to Anderson and Black (1997) it is good practice, and ensures that nothing is missed, to adopt a systematic set pattern for the examination, proceeding from the superficial (skin and soft tissues) to the deep structure (bone and joints) and from the local to the general.

The sequence of a comprehensive examination should be: a general survey, mental status, skin, musculoskeletal system, cardiovascular and neurological systems, followed by specific peripheral neurological and vascular systems and the important aspect of footwear (see Ch. 18).

The purpose of this chapter is not to give detailed information about the physical examination, but rather to provide an overview of those aspects likely to be performed in routine clinical practice. More detailed books are available (Merriman & Turner 2002) and there are various journal articles on each aspect of the process.

The general survey should give an overall impression of the patient’s general attributes, but these may vary according to socio-economic status, nutrition, genetic makeup, early illness, gender, and the country and era of birth. The overview should encompass areas such as:

Mental status

The patient’s mental status should be observed throughout the consultation, and the appropriateness of behaviour and the ability of the patient to comply with any management plan suggested should be noted. Level of consciousness can be evaluated by observing the patient’s responses to verbal and tactile stimuli and their alertness during the interview or clerking process. For example, this may indicate lethargy or stupor. During the short walk to the surgery from the waiting area, and while seated during the interview, the practitioner should observe the patient’s posture and motor behaviour and look for restlessness, agitation, bizarre postures, immobility or involuntary movements, along with pace, range, character and appropriateness of movements. The patient’s dress, grooming and personal hygiene can be evaluated in terms of neglect or fastidiousness. The facial expressions during rest and interactions should be observed for anxiety, depression, elation, anger or withdrawal. The mood of the patient should also be assessed to gauge the level of happiness, elation, indifference or anxiety. All may give clues as to how the patient views the current problem, how it is affecting his or her daily activities and how the patient may respond to suggestions about altering behaviour patterns adversely affecting their feet (e.g. inappropriate footwear).

Skin (see also Chs 2 and 3)

Look and observe, touch and palpate skin over the foot and lower limb and observe the following:

It is important to note any lesions, their anatomical location, whether they are generalised or localised, their arrangement (linear, clustered, dermatomal), the type (macule, papule, bulla, tumour, etc.) along with colour (red, brown, white, mauve) and whether raised or indurated.

Nails (see also Ch. 3)

Musculoskeletal system (see also Ch. 8)

The musculoskeletal system should be assessed using a screening method to ensure that lower limb manifestations of systemic disorders are encompassed within the assessment process. This assessment will include an inspection of the joints and the surrounding tissues, and observation of the following:

When examining a patient with a suspected musculoskeletal problem and presenting with painful joints it is important that the practitioner is gentle and moves the joint slowly. It is a difficult balance to achieve between being gentle and not being afraid to cause some discomfort in order to ensure proper examination to uncover the true cause of the complaint.

Each joint complex within the foot should be assessed individually, comparing one side with the other. Thus the ankle, subtalar and midtarsal joint complexes should all be assessed and compared with the corresponding joint complex on the other limb, and an assessment should be made of the range of motion normally expected for that complex, giving due regard to the age and sex of the patient. The first and fifth ray (Fig. 1.2) should be included in this assessment, and the foot should also be viewed holistically (i.e. both weight bearing and non-weight bearing). Where rheumatoid disease is suspected, it may be necessary to make an individual assessment of the metatarsal joints by gripping the forefoot across the metatarsal heads and squeezing gently transversely.

Footwear (see also Ch. 18)

Footwear gives a variety of clues as to diagnosis, and therefore it should also be examined during the patient’s first visit. Footwear should initially be checked for size, shape, style, suitability for the patient’s foot and occupation and indications of (abnormal) wear marks. Abnormal wear on the soles and heels of the footwear will give some indication as to the gait and weight-bearing patterns of the gait cycle. Inspection of the outer sole and insole can also provide valuable clues about the relative pressures occurring during the foot-flat and take-off phases that occur during mid- and forefoot postures. The shape or distortion of the upper also gives important data as to abnormal frontal plane motion. Abnormal wear of the sole, such as a circular pattern across the forefoot, suggests a rotational element or circumduction of the forefoot on the rearfoot typical of a rearfoot varus. Some wear patterns might suggest particular gait patterns (Anderson & Black 1997):

excessive wear at rear edge along entire edge – calcaneal gait, as in calcaneal gait of spina bifida

excessive wear at rear edge along entire edge – calcaneal gait, as in calcaneal gait of spina bifida excessive wear on lateral side – supinated foot from pes cavus, weakness of evertor muscles such as peroneal, as in peroneal muscular atrophy

excessive wear on lateral side – supinated foot from pes cavus, weakness of evertor muscles such as peroneal, as in peroneal muscular atrophyDeformity at heel counters, which may suggest excessive pronation or supination, should also be noted.

Vascular assessment (see also Ch. 12)

As podiatry moves to evidence-based systems of healthcare, podiatrists need to produce evidence that vascular assessment of presenting patients is beneficial. This does not mean the use of more sophisticated equipment, but the clinical ability to diagnose accurately possible risk factors from signs and symptoms and simple evaluative tests. Those patients potentially at risk of lower limb amputation and receiving podiatric care are nearly four times less likely to undergo such amputation than those not receiving podiatric care (Sowell et al 1999). However, it is essential podiatrists do not depend solely on equipment to make their diagnoses, but instead rely mainly on their clinical and physical examination skills. Equipment is expensive, the results obtained are liable to misinterpretation, and there are problems of validity and reliability.

The vascular section of the patient history and the physical examination is vitally important, and a misdiagnosis of vascular disease may result in significant morbidity (Nelson 1992). Podiatrists must be acutely aware of the potential limb loss, gangrene, ulceration and infection attributed to underlying arterial disease, and therefore the need for a peripheral vascular evaluation. Infection management, wound management and preoperative assessment, all require appropriate evaluation of the vascular status of podiatric patients. Hoffman (1992) suggests that ‘with non-invasive arterial evaluation, the clinician must have a diagnosis in mind before initiating the testing, know exactly what data need to be documented, and be able to question the validity of what is being recorded’. Podiatrists understand the need for a sufficient vascular supply and thus must have the ability to evaluate that supply, ensuring that there is sufficient flow entering the leg or foot to sustain normal nutrition, to heal an existing ulcer or to sustain nutrition following surgery, depending on other factors, such as age.

Pain is a common symptom of vascular disease. The three components of the vascular ‘tree’ – arterial, venous and lymphatic – all have differing manifestations and pain severity. It is imperative that practitioners differentiate between the different types of pain, and differentiate between ‘rest pain’ and the night cramps of a venous disorder. The patient with rest pain complains of intense burning in the toes, the severity increasing with coldness or when the foot or leg is elevated; they may state that they obtain relief by putting the foot into the dependent position by hanging the limb out of the bed. This severe, persistent pain is associated with ulceration or gangrene, and is indicative of a more severe arterial disease. A sudden or abrupt onset of severe pain may suggest an acute arterial or venous obstruction. In the acute arterial occlusion the pain is immediate and persistent. It may be accompanied by a sensation of coldness, tingling and numbness distally to the occlusion site. On the other hand, the pain associated with venous occlusion is similar to that of phlebitis, which is characterised by a severe ache over the involved vein. There may also be an accompanying burning or swelling of the ankle and foot.

The ‘classic’ pain normally found with chronic arterial insufficiency is termed ‘intermittent claudication’. This symptom is transient, is usually induced by exercise and is characteristically described as cramp, ache, tiredness or tightness of the associated muscles (usually the calf, but it can be the buttocks or the small intrinsic muscles of the foot). The main diagnostic criterion is that rest relieves the pain. The clinician must differentiate between orthopaedic and neurological conditions producing pain and the pain of intermittent claudication. Claudication distance can be evaluated using external factors, such as the distance the patient can walk by counting the number of lamp posts, or between two known landmarks, or clinically by the use of a treadmill. The latter allows variations of speed and of slope, and this helps in determining which factors make the situation worse. This allows the clinician to guide the patient as to what pace to take and what characteristics of the landscape to avoid (e.g. advising the patient to find routes that avoid hills). The ischaemia from acute or chronic arterial occlusion will ultimately lead to ischaemic neuropathy. The pain associated with this is sharp and shooting but poorly localised in nature.

The ability to heal is of paramount importance, especially where elective surgery is considered. Thus the clinician must be able to hypothesise and predict healing ability. Normally, adequate blood flow equates with healing ability. However, certain conditions – such as anaemia, alcoholism, uncontrolled diabetes, some connective tissue diseases and poor nutrition – refute this general assumption. Poor nutrition may be found in the elderly or alcoholics, and may result from inadequate oxygenation. Simple questions such as ‘How quickly does your skin normally heal after it has been damaged?’ should be used alongside a visual inspection of skin. It is important to realise that the physical examination should correlate with the signs and symptoms described by the patient. Where there is a lack of correlation, a double check or further more detailed investigations may be warranted. For example, pedal pulses may be absent, but on its own this sign may be insignificant; similarly, the presence of pedal pulses does not necessarily indicate adequate pedal perfusion.

The most significant findings aiding clinicians to diagnose the presence of peripheral arterial disease are abnormal pedal pulses, a unilaterally cool extremity, prolonged venous filling time and a femoral bruit. Other physical signs help determine the extent and distribution of the disease, but findings such as abnormal capillary refill time, foot discoloration, atrophic skin and hairless extremities are unhelpful to diagnosis. Within the pedal pulses the absence or diminution of the posterior tibial pulses is a more accurate indicator than is an absent dorsalis pedis pulse (Criqui et al 1985).

Palpation of pedal pulses is crucial (Nelson 1992) but clinical experience indicates that there is lack of precision associated with these pulses (Kazmers et al 1996). Each clinician has a different ability to palpate these pulses. In the foot the pedal pulses to be palpated are the posterior and anterior tibial and the dorsalis pedis. The dorsalis pedis pulse is palpated lateral to the extensor hallucis tendon at the base of the first metatarsal; the anterior tibial pulse is found at the front of the ankle; while the posterior tibial pulse is located below and behind the medial malleolus, with the foot slightly inverted. Unfortunately there is no standardisation of gradation of pulses or how they are recorded. Thus confusion exists as to how they should be recorded, with adjectives and verbs being used to describe the quality, rhythm and rate of the pulses as well as the amplitude. The most frequently used scale is (Kidawa 1993, Nelson 1992):

Baker (1991), suggests that pulses should be recorded as normal, decreased or absent. He does, however, anticipate a fourth category, where pulses are greater than expected. As the assessment is subjective, it is probable that these descriptions are all that is required.

Clinicians demonstrate fair to almost perfect agreement when stating a pulse was present or absent, but disagreement occurs when attempting to distinguish between normal and reduced pulses. Where both pedal pulses are absent there is more likelihood of vascular disease than when only one is absent (Reich 1934, cited in McGee & Boyko 1998). This is because where the dorsalis pedis pulse is absent, the posterior tibial pulse will act as a collateral supply, and vice versa. The reproducibility and accuracy of pulse palpation can be increased by undertaking the assessment under unhurried, good, quiet conditions.

The foot and lower extremities should also be inspected, taking account of colour, texture of skin, trophic changes, hair growth, oedema and ulceration. For further information on vascular disease, see Chapter 5.

Oedema of the lower leg or foot can be the result of a variety of diseases. An assessment of whether the oedema is unilateral or bilateral may suggest if it is local or regional in the former or systemic if the latter. It must also be differentiated by palpation. Is it pitting (i.e. soft in nature, leaving a depression after 15–30 s) or indurated (non-pitting)? Oedema associated with systemic disease is generally pitting, occurring bilaterally and involving the whole leg or foot to the level of the toes. Swelling of venous origin may also be pitting, but it is usually unilateral, and the oedema of varicosity or venous stasis is obvious due to bulging varicosities of the perforating veins just above the medial malleolus during weight bearing. There may also be haemosiderosis or brownish pigmentation around the site.

Ulceration may be one of the first external signs and symptoms of arterial disease. Ischaemic or arterial ulcers are usually painful and are found on the anterior or lateral lower leg above the ankle, whereas venous ulcers are usually painless and found on the medial lower leg just above the medial malleolus. Table 1.1 highlights the differential diagnosis between arterial and venous insufficiency.

Table 1.1 Signs and symptoms of peripheral vascular disease

| Arterial insufficiency | Venous insufficiency |

|---|---|

| Acute | |

| Chronic | |

Where pedal pulses are not palpable Doppler studies may help. The Doppler scanner is one of a number of non-invasive evaluation techniques available to some podiatrists. The Doppler can be used to extend clinical examination by detecting pulses over a very wide range. Therefore it is primarily useful for measuring distal blood pressures. The use of the Doppler scan has become more widespread in podiatric practice, but the successful use of this device depends on a number of factors. The tip of the Doppler probe must be coupled to the skin using an ultrasound-coupling medium, and the angle of the probe to the artery is important. The correct range of this angle has been reported to be from 45° to 60°, but there is debate about whether this angle is to the skin or to the artery (Baker 1991, Hoffman 1992). Whatever the angle, the probe should be placed in the direction of the heart. Light application of the probe to the skin surface is sufficient to ensure good detection in most cases. If excessive pressure is applied, occlusion of the artery is possible. Arteries and veins generate characteristic signals, which must be differentiated. The normal distal artery has a biphasic or triphasic sound, with a brisk systolic upstroke followed by a less prominent early and mid-diastolic component (Baker 1991). In occlusive arterial disease the systolic component may be less prominent, with few or no diastolic parts. In severe disease there may be only one continuous sound. Large and medium veins produce a low-frequency sound, which has often been likened to that of wind blowing through trees (Baker 1991). The slower the blood flow, the lower the audible pitch.

The most common use of Doppler is to measure the ankle–brachial index (ABI) or ankle–arm index (AAI). Ankle blood pressure should be approximately 90% of the brachial artery systolic pressure (Nelson 1992). The ABI is usually classified as shown in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 The ankle–brachial index (ABI)

| Pressure/ABI | Indicator |

|---|---|

| 0.9–1.00 | Normal |

| 0.5–0.9 | Claudicators |

| < 0.5 | Ischaemia |

| 0.1–0.2 | Impending gangrene |

To measure the pressure at the ankle, the cuff is placed around the ankle of a supine patient with the foot at the same level as the heart. The sounds through a pedal vessel are located and the cuff is slowly inflated until no sounds are detected. The cuff is then slowly deflated until a sound is heard, and the pressure of the ankle cuff is noted. The arm, or brachial, pressure is also noted. The ankle measurement is divided by the brachial reading and the resultant figure (the ABI) is recorded. However, care needs to be used when interpreting the results of the ABI. If the ABI is 1 there is good flow velocity, this indicates only the adequacy of blood flow at the ankle level. It does not indicate adequacy of any flow below this level. In diabetes, in particular, there may be distal occlusions in the foot, and thus ankle blood flow cannot be used to estimate blood flow in the foot (Hoffman 1992). The ABI can be falsely elevated in the presence of calcifications of arteries. Thus both the sounds noted with the Doppler and the ABI should be considered prior to assuming that a correct ABI has been noted. Where, for example, the ABI is 1.2 but there is a low-pitched, long, swishing sound on the Doppler, an assumption that there is some calcification is more likely to be correct.

Other sophisticated techniques, such as photoplethysmography, Perthe’s test, the Brodie/Trendelenberg test, percussion and thermography, may be used to measure various components of the vascular system, but this is usually the realm of either researchers or more specialist clinical areas.

Neurological assessment (see also Ch. 6)

Ziegler (1985) stated that there is ‘in all clinical medicine a subtle competition between the value of information given us by increasingly sophisticated instruments and that by our own eyes, ears and hands’. This is true of neurology and the neurological examination: ‘It still requires the skills of the clinician to be attuned to signs and symptoms within the history which suggests that further neurological tests might be advised to identify the problem or cause of these symptoms.’ As DeMeyer (1998) states: ‘Since the examiner cannot do every possible test on every patient, intelligent utilisation of the history may shorten the examination yet make it more informative.’

The way in which a neurological examination is conducted will depend on the age of the patient and the presenting complaint. Green (1974) suggests that there is a trinity required in examination of the elderly:

In a child the neurological examination may be handicapped by lack of cooperation, and thus observation may provide the most information (Bernstein 1987, Singh 1978). Singh (1978) suggests it is not generally feasible to have a scheme of examination for infants. Height, weight, ambulatory status and general activity level may be required information in children (Bernstein 1987), but it is good practice to record these data for all patients.

The history and the physical examination are vitally important components of the evaluation, often determining the diagnosis and the need to plan further diagnostic tests (Magee 1977). Although gait is discussed later, the patient should be observed as he or she walks into the clinic and as the history is taken. Thus, again, observation is highlighted as a key component, with the diagnostic tools of our ears and eyes being the mainstay of the examination. The most vital, and often forgotten, part of any neurological examination is communication. Inform the patient about what each test is, what is required of them, and why it is being carried out.

Motor system

The main aims of examining the motor system are to:

The examination should follow a routine:

not necessarily in this order.

Inspection

Inspection of the patient begins as soon as he or she is called in the waiting area. The clinician should observe as he or she is walking towards them, looking for abnormalities of posture, gait or coordination or involuntary movements. Inspect for wasting, and note symmetry, looking specifically for distribution. Note any fasciculations (a spontaneous contraction of muscles, usually of small muscle fibres) that imply an LMN lesion (e.g. motor neuron disease or a ‘slipped disc’ (prolapsed disc)). Look also for tremors, and note whether these are fine or coarse, and whether they occur at rest or during movement (intention tremor).

Palpation and assessment of tone

Palpate the muscles and muscle groups, looking at the muscle bulk and for tenderness (suggesting a myositis); also at this point note the tone. This evaluation is subjective and will require experience. Attempt to identify hypertonia (high resistance then sudden release – usually UMN) or hypotonia (LMN and cerebellar lesions).

Assessment of power

Assess the muscles individually or as a group. Muscle power should be classified using the Medical Research Council (MRC) grade (Table 1.3). When a weakness is found or suspected, attempt to classify the origin as UMN or LMN.

Table 1.3 Medical Research Council (MRC) classification of muscle power

| Grade | MRC grade of muscle strength |

|---|---|

| 0 | No movement |

| 1 | Flicker of movement visible |

| 2 | Movement possible – gravity eliminated |

| 3 | Movement possible against gravity, but no resistance |

| 4 | Movement against resistance possible, but it is weak (can be divided into 4+ or 4−) |

| 5 | Normal |

(adapted from Marsh 1999)

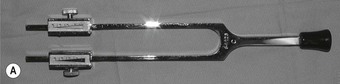

Assessment of reflexes

Podiatrists should test the knee and ankle reflexes. According to DeMeyer (1998) neurologists persistently misname the muscle stretch reflexes (MSRs) ‘deep tendon reflexes’. The MSR response should be elicited using a tendon hammer (Fig. 1.3). The MSRs tested by podiatrists are the quadriceps reflex, which assesses the fourth lumbar nerve (L4), and the Achilles reflex. Comparison of the reflex should be made with the corresponding one on the opposite limb and with ‘normal’. The response should be recorded as normal, brisk, reduced or absent. If the reflex is absent, attempt to produce it by reinforcement methods – ask the patient to interlock fingers and pull them apart while attempting to elicit a response in the knee (Jendrassik’s manoeuvre) (Merck Manual 1997).

The Babinski reflex is tested using moderate pressure, not light stroking, as this may produce only a tickle response rather than a reflex. If this test is inadequate then the Chaddock reflex test can be performed (DeMeyer 1998, Magee 1977). This involves stroking the side of the foot with a blunt instrument and looking for the same extensor response of the hallux as occurs in the Babinski response. The result should be recorded as either a normal plantar response (hallux and toes curl and claw plantarly), reduced or absent, or a Babinski response (hallux extends dorsally, the toes may or may not also fan out). However, it should be noted that a Babinski response is a normal finding in infants up to 18 months of age (Bernstein 1987).

Assessment of coordination

The lower limbs are assessed using the heel–shin test. Ask the patient to place his or her right heel on the left shin and slide it up and down the shin, and then to repeat the test on the other side using the alternate limb.

Motor and sensory system functions

It is only necessary to perform muscle testing for strength, size and symmetry. In the foot this will normally involve testing of the dorsiflexors, plantarflexors and invertors and evertors.

Observation during the examination will demonstrate evidence of atrophy, fasciculations and involuntary movements, along with the symmetry of one leg/foot/side to the other. Passive movements of the various muscle groups can determine fluidity of movement and will elicit lead-pipe rigidity (basal ganglia disorder) or clasp-knife should movements (pyramidal tract disorders).

Sensory investigations

Patients are normally aware of some change in sensation and may describe numbness, paraesthesia or altered sensation, which will indicate a sensory pathology or dysfunction. Examination of the sensory system is part of the routine examination. An attempt should be made to identify the modality of loss and also its distribution (i.e. correlate it with a dermatome or a sensory peripheral nerve).

Light touch

Dab a cotton wool ball onto the skin lightly. If an area of sensory diminution is suggested, attempt to map this out. Start from the area of decreased sensation and progress to an area of normal sensation.

Pin prick

As pain and temperature run in the same tract (spinothalamic), it is necessary to perform only one of the tests rather than both, unless some concern or questions remain having performed one test. Magee (1977) suggested using the pain test and leaving temperature, as does Marsh (1999). However, DeMeyer (1998) suggests that in the screening neurological examination the clinician test first for temperature and reserve the pin prick test for cases where there is a neurological problem or sensory findings (Fig. 1.4).

Vibration

The posterior column is the location of sensing position and vibration. These are evaluated at the ankle and distal aspects of the hallux. Vibration can be grossly evaluated using a 128 Hz tuning fork at the malleolus or the medial border of the hallux (Fig. 1.5). Patients should be aware of a buzzing sensation (Marsh 1999). The patient should close his or her eyes and indicate when they can no longer feel the sensation. More precise and recordable measurements are obtained by using a Rydel–Seiffer tuning fork with a graduated scale (Fig. 1.6) or, better, the biothesiometer (Fig. 1.7) or neurothesiometer (Fig. 1.8). However, the latter two are fairly expensive pieces of equipment and should be reserved for those either undertaking research or conducting examinations in those with a degradable sensory dysfunction such as diabetes.

Figure 1.5 Normal 128 Hz or middle C tuning fork. It measures gross vibration sense but gives no scalar quantifiable data.

Figure 1.6 Rydel–Seiffer (RS) tuning fork with a graduated scale (A). Scalar measurement and quantifiable data from the RS tuning fork (B).

Figure 1.8 A neurothesiometer. It uses a battery pack but has a vibration head similar to that of a biothesiometer.

In elderly patients, reduced perception of vibration, pain and touch at the ankle and a diminished ankle reflex are not necessarily clinically significant. Testing of more sophisticated sensory functions, such as stereognosis and two-point discrimination, is unnecessary for a routine clinical neurological survey.

In evaluating the motor and sensory systems the aim is to determine the anatomical site or pathway affected, localising the lesions or disorder to the peripheral nerves, nerve roots, spinal cord, brainstem, basal ganglia or cerebral hemispheres. It may also be possible to differentiate between single or multiple lesion disorders. Table 1.4 outlines the main characteristics of differential diagnosis between upper motor neuron lesions (central nervous system) and lower motor neuron lesions (peripheral nervous system).

Table 1.4 Upper and lower motor neuron disease: differential diagnosis

| Differentiating factor | Upper motor neuron | Lower motor neuron |

|---|---|---|

| Location of weakness | Depends on lower motor neurons involved (which segment, root or nerves) | |

| Muscle tone | Spasticity increased in flexors in arms and extensors in legs | Flaccidity |

| Muscle bulk | Atrophy of disuse | Atrophy which is marked |

| Reflexes | Increased, Babinski reflex present | Decreased, absent |

| Fasciculations | Absent | Present |

| Clonus (rhythmic, rapid, alternating muscle contraction and relaxation brought on by sudden, passive tendon stretching) | Frequently present | Absent |

Similarly, the motor examination and gait analyses localise lesions to the neuromuscular junctions or to a particular muscle.

One further test, which has become more frequently used by podiatrists, is the monofilament test (Semmes–Weinstein monofilament). This test is used to predict foot ulceration, especially in diabetes (Armstrong et al 1998, Bell-Krotoski et al 1995, Bell-Krotoski & Tomancik 1987, Kumar et al 1991, Olmos et al 1995, van Vliet et al 1993, Weinstein 1993). Semmes–Weinstein monofilaments can be purchased as a set of 20 pressure-sensitive nylon filaments attached to a lucite rod, or as single unit (Neuropen, Owen Mumford, Woodstock, Oxford, UK) or in a pack of three (Bailey Instruments, UK). The Neuropen has a 10 g or 15 g retractable, interchangeable monofilament as well as a calibrated neurotip. The set of three monofilaments is in a boxed set of 1 g, 10 g and 75 g monofilaments, each on a lucite rod. These monofilaments have a standardised length and thickness enabling them to buckle at reproducible forces ranging from 0.0045 g to 447 g (Olmos et al 1995). This allows the amount of pressure being applied to cause buckling to be a constant force for that particular rod. The monofilament is applied perpendicular to the skin surface, and pressure is applied slowly until the monofilament bends. At that point the practitioner should request the patient to state whether they are able to determine any sensation of pressure. The 5.067 log monofilament (10 g) has been proven to be the level of pressure providing protective sensation against foot ulceration (Birke & Sims (1986) and Halar et al (1987) as cited in Olmos et al (1995)). As with any device, there are some known idiosyncrasies that a practitioner should take into account when using monofilaments and when interpreting the data obtained. Van Vliet et al (1993) found that pressure thresholds vary significantly with the duration of contact of the monofilament, thus requiring practitioners to maintain a consistent protocol when using these devices. These filaments are used to test the pressure at various places on the foot (Fig. 1.9).

The sites tested may vary (Armstrong et al 1998, Bell-Krotoski et al 1995) but the area of dermatomes of the foot should be covered. Another problem noted when using monofilaments is slippage when the filament is applied to the skin, which causes some disruption to the testing. However, this has been corrected for by the modification incorporated in the newer Weinstein Enhanced Sensory Test (WEST) (Weinstein 1993). These filaments are used daily in diabetes clinics, and together with other diagnostic or predictor factors help podiatrists to reduce possible ulceration and pressure lesions in diabetics. They are useful screening tools.

When a podiatrist detects an abnormality but is unsure of its origin they should refer the patient to a neurophysiologist for further studies and advanced testing of the nervous system. The ability of the podiatrist to determine when a patient needs to be referred is crucial to good patient management.

Gait

Analysis of gait is rudimentary and should be carried out routinely when first seeing the patient. It is best to observe the gait when the patient is unaware of being observed. The analysis can be either by simple observation or by means of various measuring devices and mechanical methods. However, most practitioners will need to rely on observation as the primary method of analysis. Observation gives data about the full gait cycle, while mechanical methods usually determine the forces and pressures through the plantar of the foot. The use of a treadmill allows the cadence to be controlled, and the patient and practitioner are in a static position while undertaking a dynamic sequence of events. Video recording enables more subtle changes or patterns to be viewed and repeated, but this is not always available. Gait analysis using video and a treadmill is shown in Figure 1.10. A long, well-lit corridor is usually sufficient for gait analysis, but experience is needed to view minor changes and compensations from more than one angle. Gait analysis requires a holistic approach to the patient, and practitioners should look at each body segment in turn, and preferably from the front, back and one side. With informed consent, and a chaperone, it is best to view a patient in a semi-undressed state (Fig. 1.11). Most of the mechanical methods are confined to use by researchers or by specialist clinicians, due to cost, experience and time factors. Although the following gives a brief outline of some of the methods available, it is by no means an exhaustive list and detailed reviews by independent researchers should be viewed prior to purchasing any equipment. The methods are subdivided into static and dynamic methods. The information obtained from using these methods is in addition to the basic knowledge obtained in the general observation and examination, and in general does not in itself lead to a diagnosis, but rather aids in making the diagnosis or is used to confirm it.

Figure 1.10 Gait analysis using video and treadmill. Using patients fully clad can lead to problems of identification.

Figure 1.11 Having gained informed consent, and with a chaperone, it is best to view a patient in a semi-undressed state (A). Rear view (B), and detailed segmental view (C), of the subject.

Static evaluation

The plantarscope shows how the plantar surface of tissues blanches on loading. It consists of a safety-glass platform over an angled mirror, allowing the clinician to view the plantar surface of the foot. The podometer is more elaborate, and combines measurements of foot size and calcaneal deviation with the reflected image. The pedobaroscope is an internally lit sheet of glass with a plastic or card interface (Anderson & Black 1997). The patient stands on the interface and reflected light produces a grey-scale image, which is stored digitally or a hard copy produced for analysis.

Dynamic evaluation

Possibly the simplest device is a sheet of black paper. The feet are dusted with chalk and the patient walks the length of the sheet or roll of paper. The resultant footprints give an indication of pressure areas, an outline of the footprint and weight-bearing surface, the angle and base of gait, as well as stride length.

The Harris and Beath mat is a rubber mat with ridges forming squares crossed by smaller squares which, when inked and overlaid with paper, allow the footprint to be left on the paper. The highest pressures are recorded.

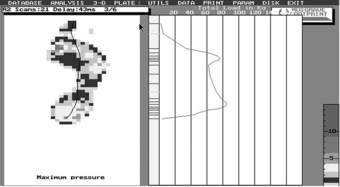

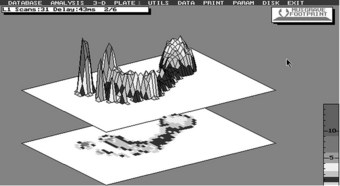

The dynamic pedobarograph is a variant of the pedobaroscope and is used as a research tool. The resolution of this device is excellent but careful analysis of the results is required, and this takes experience and time. There are numerous commercially available devices of this type. One of these is the Musgrave foot pressure gait analysis system, which gives relatively good resolution of the pressure distribution of the plantar of the foot in real-time mode as well as static impressions. The pictorial results can be used for a variety of different analyses, and the device has become quite sophisticated. However, the system needs to be housed in a walkway. It has the advantage of giving highly visible pictures which enable discussion and visualisation of the problems with patients (Figs 1.12 and 1.13).

Figure 1.12 Musgrave visual representation of centre of load of a typical rheumatoid disease patient.

Figure 1.13 A three-dimensional visual representation showing maximum pressures in a rheumatoid patient.

The Kistler force plate provides information about the forces acting through various joints and through the foot in all three axes. The interpretation of the resulting ‘stick’ figures is complex, requiring expertise and experience, and therefore this is definitely a tool for the researcher.

This is very much the case for these and other in-shoe pressure devices, which are too numerous to detail. In most cases the devices are upgraded or new versions and new devices are coming onto the market, all claiming to be repeatable, reliable and giving valid measurements, as well as ease of use.

For most clinicians, observation of gait and a Harris and Beath mat or other pressure-sensitive paper device will be sufficient.

Other soft tissues

Some clinical signs should be given greater importance than others. The most important of all clinical signs is that of the inflammatory process, classically described as rubor, calor, dolor and tumor – redness, warmth, pain and swelling. Loss of function is another classic sign of the inflammatory process. Again, accurate recording of the features will enhance clinical practice. The record card should indicate:

The treatment of an acute or subacute inflammatory lesion takes priority over a deformity, while a spreading infection requires immediate referral for further investigation and management (Anderson & Black 1997).

Biomechanical examination

Assessment of the joint complexes of the foot and ankle and their relationships to the lower extremity and spinal column are vital to any diagnosis of foot problems of a structural or functional nature. Motion of any joints within their normal range should be pain-free and unrestricted. Pain, crepitus, restricted movement or excessive motion may suggest a joint pathology. Deformity affecting either of the osseous components of the joint, or tenderness affecting the surrounding structures on palpation may also indicate pathology. The various complexes of the foot and ankle should be assessed and examined individually.

Further investigations

Some simple further tests may be initiated by podiatrists to enable a more reliable diagnosis and a suitable management plan to be conducted. These tests require taking samples of various constituent parts of the body, and it is necessary to communicate to the patient why these samples are needed and what information is expected to be obtained from them.

Discharge

Bacteriological examination of pus and other wound discharge may help diagnose the particular infective agent present, enabling the practitioner to establish the most appropriate management plan. It is of paramount importance to establish the nature of the organisms present in wounds when the level of risk to the patient is high. Thus, high-risk diabetics with vascularly compromised or insensitive feet should clearly have the identity of any infective agent established as a matter of urgency. Where streptococcal or anaerobic organisms are suspected and the wound is not healing, it is vital to identify the organisms to ensure an appropriate management plan.

Skin and nail

Research has demonstrated (McLarnon et al 1999, Millar et al 1996) that nails with suspected fungal infection must be mycologically examined prior to reduction by nail drill, as this process carries risks in terms of respiratory and ocular effects for the podiatrist. Scrapings can be examined for fungal infection, and should be collected when there is any suspicion of contamination by fungi. Scrapings are collected by scraping the edge of the skin lesion with a scalpel. The scrapings are placed in some form of container for transport to an approved laboratory. Scrapings are also taken from the affected nail at the advancing edge or the distal aspect of the nail and these too are placed in a transport container. It is important that, when mycotic nail infections are to be treated, (a) the fungus is identified prior to drilling or reduction, and (b) appropriate personal protective equipment is utilised during the reduction process.

APPLYING CRITICAL THINKING TO THE INFORMATION GATHERED

Data gathered through the above processes may be either partial or complete, but all data require analysis. This is achieved using the following steps:

DEVELOPMENT OF THE DIAGNOSIS

Establish a problem list and name each problem for the patient’s record. This may be that the patient has:

From this list, organise a plan to manage the problems both individually and holistically. For each active problem requiring attention, develop a plan, which may have three component parts: diagnostic, therapeutic and educational. It is best practice to include the patient in making the plans, as failure to do so may lead the patient to be non-compliant. The goals, attitudes, economic means, as well as competing responsibilities affect the practicality, acceptability and wisdom of the plan, and involving the patient from the very beginning improves the chances of success.

CREATING THE RECORD

The patient’s record is not just a record of what was done to the patient by the practitioner – it is a legal documentation of the consultation process (see also Ch. 16). There are certain legal, ethical and professional requirements for podiatric records. (In the UK these are laid down by the Health Professions Council (HPC), Society of Chiropodists and Podiatrists (SCP) and Department of Health (DoH); there are corresponding appropriate bodies in other countries.) The record documents the findings, the assessment of the nature and causes of the problem, the diagnostic conclusions as well as the plan for the management of the patient and their condition(s). The record should be accurate, clear, well organised, up to date and legible. It should emphasise important features and omit the irrelevant. Data not recorded are lost, but data buried in trivia can be overlooked. Record all positive data that contributed to the assessment, and describe the negative data, such as the absence of a sign or symptom, if this has affected or enabled a diagnosis. Remember that a patient is entitled to ask to see their health record; therefore, stick to factual information and avoid litigious phrases about the patient.

A good record leads to good communication between the practitioner and the patient and between other professionals who may participate in the patient’s care. It is also helps in medicolegal cases.

Abbreviations and symbols used should be those commonly used and understood (SCP 1999), and measurements should be in centimetres and not obtuse inaccurate schemes of measurement such as ‘pea-sized’. Where appropriate, diagrams add greatly to the clarity of records (Bates 1995).

The SOAPE system is a well-established recording method, and ensures accuracy and completeness of data for each consultation. The method consists of writing the letters perpendicularly down the record card, and adding information in the following scheme:

CASE STUDY 1.1 Rheumatology referral

A young female patient aged 31 years, with an office occupation, presents to a podiatrist with a letter from her GP. The letter invites the podiatrist to see and advise about a metatarsalgia the patient has been experiencing for a few weeks.

On the day of the consultation the patient explains that she has experienced pain in the forefoot across the ‘ball’ of her foot. She has noticed it in both feet, recently, with sometimes what she thinks is swelling of both feet. The pain is worse in the morning and takes about an hour or so to lessen. Recently, she has had difficulty walking up stairs and has taken to using the lift in her office building rather than taking the one flight of stairs. She has noticed that her hands have become sore and tender, especially over her small finger joints, and using the keyboard has become more difficult. She says she has no other complaints.

On examination you notice that her feet are swollen and feel hot to the touch over the metatarsal areas. Palpation of the areas suggests some swelling, and they are tender to the touch. Her hands also display some swelling across the metacarpophalangeal joints and the proximal interphalangeal joints. Both hands and feet appear to be bilaterally involved, with symmetry across the joints affected. When you lightly grasp the metatarsal heads just proximal to them and squeeze the foot she gasps in pain and is obviously distressed by the technique.

She is referred to the rheumatologist with a possible diagnosis of rheumatoid disease, which is confirmed a few weeks later with a positive rheumatoid factor in her blood serum.

CASE STUDY 1.2 Diabetes mellitus

A male patient, 46 years of age, presents with problems with cutting nails, a history according to the GP’s letter of ingrown toenails and infections not responding well to antibiotics.

The patient is 1.67 m tall and says that he weighs about 95 kg. He states that his problems have persisted over the last 6 months or so, during which time he has had difficulty cutting his nails – after cutting them they seem to become infected on a regular basis. He has had numerous courses of antibiotics but they do not seem to clear the infection. On examination it is noticed that the great toe is swollen and inflamed, with pus exuding but no sign of a spur.

Further questioning suggests a history on his mother’s side of the family of diabetes and his father was also a diabetic. This suggests that the patient should be questioned about his diet, his weight gain, his social drinking and work.

Recently, the patient has noticed that he cannot concentrate for as long as usual, and that he is drinking ‘quite a lot of water’ more often at his place of work, but has put this down to the office being too hot. His weight has been steadily increasing in the past year but he has put this down to ‘middle-age spread’ and lack of exercise.

The symptoms suggest type 2 diabetes and the patient is referred back to his GP who conducts the necessary tests with a positive result.

Anderson EG, Black JA. Examination and assessment. In: Lorimer D, et al, editors. Neale’s common foot disorders: diagnosis and management. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1997.

Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Vela SA, et al. Choosing a practical screening instrument to identify patients at risk for diabetic foot ulceration. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158:289-292.

Baker JD. Assessment of peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America. 1991;3(3):493-498.

Bates B. A guide to physical examination and history taking, 6th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1995.

Bell-Krotoski J, Tomancik E. The repeatability of testing with Semmes–Weinstein monofilaments. Journal of Hand Surgery [Am]. 1987;12(1):155-161.

Bell-Krotoski JA, Fess EE, Figarola JH, Hiltz D. Threshold detection and Semmes–Weinstein monofilaments. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1995;8(2):155-162.

Bernstein AL. Neurologic examination in children. Clinics in Podiatric Medicine and Surgery. 1987;4(1):11-20.

Criqui MH, Fronek A, Klauber MR, et al. The sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value of traditional clinical evaluation of peripheral arterial disease: results from non-invasive testing in a defined population. Circulation. 1985;71(3):516-522.

DeMeyer W. Pointers and pitfalls in the neurologic examination. Seminars in Neurology. 1998;18(2):161-168.

Green D. Neurologic examination of the elderly. New York State Journal of Medicine. 1974;74(6):969-972.

Hoffman AF. Evaluation of arterial blood flow in the lower extremity. Clinics in Podiatric Medicine and Surgery. 1992;9(1):19-56.

Kazmers A, Koski MF, Groehn H, et al. Assessment of non-invasive lower extremity arterial testing versus pulse exam. American Surgeon. 1996;62(4):315-319.

Kidawa AS. Vascular evaluation. Clinical Podiatric Medicine and Surgery. 1993;10(2):187-203.

Kumar S, Fernando DJS, Veves A, et al. Semmes–Weinstein monofilaments: a simple, effective and inexpensive screening device for identifying diabetic patients at risk of foot ulceration. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 1991;13(1–2):63-67.

McGee SR, Boyko EJ. Physical examination and chronic lower-extremity ischemia: a critical review. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158(12):1357-1364.

McLarnon NA, Burrow JG, Aidoo KE 1999 Ocular risk to podiatrists from human toe nails. Unpublished work, PhD thesis, Glasgow Caledonian University.

Magee KR. The neurologic workup by the primary care physician. Postgraduate Medicine. 1977;61(3):77-80. 83–86

Marsh J. History and examination, Mosby’s crash course. London: Mosby; 1999.

Merck Manual Medical Library, Online medical Library. found at www.merck.com/MMPE/index.html, 1997.

Merriman LM, Turner W. Assessment of the lower limb, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. (ISBN 0-443-071128)

Millar NA, Burrow JG, Hay J, Stevenson R. Putative risks of ocular infection for chiropodists and podiatrists. Journal of British Podiatric Medicine. 1996;51(11):158-160.

Nelson JP. The vascular history and physical examination. Clinics in Podiatric Medicine and Surgery. 1992;9(1):1-17.

Olmos PR, Cataland S, O’Dorisio TM, et al. The Semmes–Weinstein monofilaments as a potential predictor of foot ulceration in patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes. American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 1995;309(2):76-82.

Ricketts P. Did you consent to treatment? http://www.pfiworld1.cwc.net/GPQ/patient1.htm, 1999.

Singh M. Neurologic examination of an infant. Indian Journal of Paediatrics. 1978;45(371):3086-3089.

1999 The Society of Chiropodists and Podiatrists Guidelines on Minimum Standards of Clinical Practice. London: SCP, 1999.

The Readers Digest Universal Dictionary 1987. Readers Digest Association Limited, London.

van Vliet D, Novak CB, Mackinnon SE. Duration of contact time alters cutaneous pressure threshold measurements. Annals of Practical Surgery. 1993;31(4):335-339.

Wanheng C, Xiaoxiang L. Wisdom in Chinese Proverbs. Singapore: Asiapac Books; 1996. (ISBN 981-3068-27-2)

Weinstein S. Fifty years of somatosensory research: from the Semmes–Weinstein monofilaments to the Weinstein Enhanced Sensory Test. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1993;6(1):11-22.

Ziegler DK. Is the neurologic examination becoming obsolete? Neurology. 1985;35(4):559.