Chapter 29 Health and safety in podiatric practice

INTRODUCTION

Health and safety traditionally was concerned with providing technical solutions to health and safety problems, or providing items such as respiratory protective equipment to give the required protection for levels of dust exposure based on extensive dust measurements. Most accidents occur because the culture of the organisation or employees is incorrect, because production demands (increased patient numbers) create tunnel vision, or because work was ‘always done that way’. In the past no one analysed the work to identify the system of work, because people were ‘too busy’, because insufficient attention and priority were given to health and safety, and because of the ‘it won’t happen to me’ syndrome.

Podiatry is no exception to this traditional view of what health and safety is about. Unfortunately, health and safety is a major issue that both union members and all working people think unions should concentrate on. Within podiatry, the health, safety and welfare concerns are also high, with areas such as work-related upper-limb disorders, repetitive strain injury (RSI) and musculoskeletal problems, especially lower back and neck problems, becoming increasingly common. Stress is also an ever-increasing problem for podiatry staff. According to Williams (1999), the commonest causes of work-related stress currently are overload and bullying, and both of these are apparent in podiatry, especially in the National Health Service (NHS).

Increased patient caseloads have been imposed and met as the modern NHS strives to achieve ‘target’ figures with ever-decreasing resources. In podiatry, there is an increasing demand for services, alongside down-sizing in some localities and the introduction of new working practices such as decontamination of instruments. New criteria are being imposed to reduce the number of patients seeking podiatric help, and increasingly it is the high-risk patients that the NHS manages. This change brings with it increased stress and workload demands, and the requirement for higher levels of concentration and higher skills, including those of communication, manual dexterity and professionalism.

Stress should be thought of in terms of outcomes: it produces low morale and reduces productivity, and it increases both short- and long-term absenteeism as well as mistakes, which may have adverse effects on patients and potentially the podiatry service that can be delivered when litigation cases ensue. As in all areas of health and safety, the risk assessment of podiatric workplaces and practices should include stress and stress-related or stress-induced hazards and risks.

Health, safety and welfare require risk assessment, followed by management of the hazards and risks to reduce the risk factors identified to the lowest level possible. The concept of risk assessment is similar to that of clinical assessment (see Ch. 1). It is important that, in dealing with patients, practitioners consider not only the health, safety and welfare of their patients, but also their own health, safety and welfare.

Prior to the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 (HASAW Act) becoming law, health and safety legislation was retrospective – it was drafted or was enforced following accidents in an attempt to prevent recurrence. Within podiatry this has not changed, and health and safety is still seen as the poor relation, with little cognisance taken of risks and hazards (e.g. the introduction of single-use disposable instruments has been associated with an increased number of reports of RSI – something that many had suggested might happen). However, a problem identified by the National Patient Safety Agency is the low recording of accidents, incidents or near misses by all allied health professions, and an inability to distil specific podiatry information. The HASAW Act aimed to anticipate and prevent accidents before they happened, attempting to keep pace with new technology and changing working practices, assuming it was enforced. The philosophy behind the HASAW Act is self-regulation: for example, the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations 1994 (COSHH) and subsequent amendments to it; the Control of Noise at Work Regulations 2005 and the batch of six regulations that came into force at the beginning of 1993 (the ‘six pack’). All these regulations are based on the premise and requirement that the employer conducts a risk assessment in each particular workplace, for each work practice, and adopts appropriate control measures necessary to deal with the hazards identified and the degree of risk assessed.

This assessment approach is philosophically different from that adopted by legislation prior to the HASAW Act. The new approach requires the employer (or private practitioner) to identify, within certain minimum legal requirements, safety standards to be achieved and control measures required. However, it is not sufficient to undertake a one-off assessment. The assessment should be set within a TQM (Total Quality Management) framework. Thus, a risk assessment is carried out, a set of aims and objectives is determined to offset the hazards and risks, and then, once that set of objectives has been achieved, the process is renewed with fresh objectives. Employers must continue attempting to reduce the level of risk to the lowest level reasonably practicable.

EFFECTIVE MANAGEMENT

Effective management of health and safety, and thereby prevention of accidents and ill health within an organisation or practice, is important because of a whole range of factors, including:

Hidden costs include building and equipment damage, lost production, legal expenses, hiring replacement equipment, accident investigation time, management and administrative time, and loss of business and goodwill, etc. For example, if a bench-top autoclave were inadequately maintained and the inadequacy of maintenance resulted in an explosion, there would be considerable damage to property internally and externally.

Public disasters involving loss of life and notices in the press recalling potentially faulty consumer goods (e.g. drink bottles, food, electrical appliances) heighten public awareness that many incidents are avoidable. There is also the realisation by those injured, customers, employees, shareholders and neighbours that the key to avoidance of safety problems lies with effective management of safety. There is a growing awareness at management level of the relative costs of accidents and insurance, the requirements of legislation, and an interest in quality management systems, all considerably raising the profile of risk management with an increased need for improved health and safety practice and policies. There is also, however, an increasing risk of litigation and complaints to regulatory bodies about practitioners and their practices.

SUCCESSFUL HEALTH AND SAFETY MANAGEMENT

The correct approach to successful health and safety management is contained in five steps. These are:

There is no specific legal requirement to adopt this system. However, it may well be that in future courts and regulatory and professional bodies will look more closely at how effectively safety was managed. Failure to provide evidence that a formal system was in operation may leave practitioners exposed to both criminal and civil law penalties if an accident occurs.

SAFETY CULTURE

Health and safety traditionally was concerned with providing technical solutions to problems (e.g. providing guards for machinery to a specific standard). Accidents do not tend to occur because a guard was not up to standard or the dust mask was not quite technically correct. They are usually a result of there being no guard or dust mask at all. Those accidents occurred because the culture was not right, because production demands (patient numbers) created tunnel vision, because work was ‘always done that way’, because no one analysed work practices to identify safe systems of work, because people were too busy, and because insufficient attention and priority were given to health and safety. The problem is one of attitude. The greatest challenge to our profession is influencing and changing attitudes and behaviour. Recent research into nail dust and the hazard of dust exposure or RSI through poor equipment or poor maintenance highlights these issues for podiatrists.

SAFE SYSTEMS OF WORK

Part of an employer’s duty is to provide a safe system of work where, insofar as is reasonably practicable, the work or manner in which it is carried out is safe and without risks to health. The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) recommends five steps to a safe system of work:

All podiatric activities should adopt this system. Simple tasks such as nail cutting, scalpel work and routine maintenance of equipment should follow this approach, not just the more elaborate tasks such as nail surgery. This recommended analysis of work practices should ensure that guidelines or protocols are written, adopted and monitored, which may minimise risks to employees and practitioners alike.

Podiatrists need to be proactive in assessing their activities. There are problems with home visits due to poor working conditions, poor lighting, poor ventilation and poor posture. Are the problems being addressed, ensuring a rota of staff so that no single individual is solely undertaking domiciliary visits but instead spreading the risk across a number of members of staff and thus reducing the risk individually?

LEGAL DUTIES

The most important and broad-ranging duty of care, which must be fulfilled by employers, is described by Section 2(1) of the HASAW Act:

It shall be the duty of every employer to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health, safety and welfare at work of all his employees.

However, this duty of care does not stop at employees – employers also have responsibility towards certain non-employees, which can include visitors, contractors and also the general public (patients and their carers). This duty of care includes their overall safety, more specific concerns, such as safe entrance and exit to the practice, as well as the provision of information (e.g. fire exits, routes or emergency procedures) and training. The employer (private practitioner) is legally obliged to undertake risk assessments. Ultimate responsibility rests with the employer, but the task of risk assessment is quite likely to be delegated; in the case of the NHS this may be to safety representatives or a health and safety manager. The general duty of care owed to employees under Section 2(1) is qualified in Section 2(2) of the HASAW Act. It includes:

The employer has ultimate responsibility to ensure satisfactory standards of health and safety at work and their efficient management. The employer is defined as the corporate body (limited company), partnership, owner or proprietor.

The employer (private practitioner) may incur liability for health and safety in one of two ways.

Every employee and manager has some legal duties in this area, and these responsibilities should normally be incorporated in any job description and job title for a position within a company or practice. The delegation of responsibility should be to a competent person. Regulation 6 of the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999 (MHSWR) defines this as ‘one who has sufficient training and experience, or knowledge and other qualities, to enable him or her properly to assist in undertaking the measures needed to comply with health and safety legislation’.

Employers have a responsibility to protect the following categories of people:

To enable a practitioner to understand the practical implications of the general requirements of the HASAW Act, the practitioner will rely on regulations made under that Act and the Health and Safety Commission’s Approved Codes of Practice and Guidance Notes (e.g. Essentials of Health and Safety at Work).

A large organisation such as a Trust or Board (or Local Health Care Cooperative) or Primary Care Group or Trust (PCT/PCG) may wish to appoint a member of staff as the competent person. Many employers decide to appoint an external health and safety consultant, and where such is appointed the employer (or private practitioner) will depend on the professional skill and expertise of that consultant. However, caution is needed when appointing such a person. Practitioners should ensure that the appointed consultant is competent by, for example, checking that the consultant has sufficient training, expertise, a proven track record and also adequate professional indemnity insurance.

Employers (practitioners) may legally deflect liability to an external expert should enforcement action be taken as a result of the consultant’s neglect. This assumes proper documented procedures were in place to attest to the consultant’s suitability as a competent person. In the event of compensation being paid to an injured employee, it may be possible for the practitioner’s insurer to recover money from the consultant. Advice on the competency of consultants can be attested by contacting some of the health and safety organisations such as the Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH at http://www.iosh.co.uk; telephone 0116 257 3100).

THE EMPLOYER’S RESPONSIBILITY TO VARIOUS PARTIES

Employees

Section 2(1) of the HASAW Act requires the employer to ensure the health, safety and welfare of all employees, insofar as is reasonably practicable. It is necessary to consider within any risk assessment what is meant, or may be meant, by the phrase ‘all employees’. The employer must consider the principle of individual assessment and incorporate individual information into the risk assessment task, as required by the MHSWR. Every employer requires, when delegating tasks to employees, to take account of each individual’s capabilities with respect to health and safety and in addition provide them with the necessary information, instruction and training contained within Section 2(2)(c). The combination of these legal duties should ensure that training is provided at the following times:

Employees are also entitled to information concerning (see Case Study 29.2):

CASE STUDY 29.2 AN NHS TRUST HAS BEEN FINED FOLLOWING THE EXPOSURE OF AN EMPLOYEE TO A DANGEROUS CHEMICAL, RESULTING IN OCCUPATIONAL ASTHMA

K, a healthcare worker, was employed by B Hospital NHS Trust and part of her work was decontamination of surgical instruments and medical equipment using glutaraldehyde. In the summer of 1999, K developed symptoms, including headaches, exhaustion, coughing and sneezing, a dry mouth and rashes on her arms and feet. She was diagnosed as having dermatitis and asthma as a result of working with and exposure to glutaraldehyde. K is unlikely to work ever again.

The HSE investigation concluded there were failings in the hospital’s safety procedures and policy for work with the substance. Although employees had been told to use protective equipment when using the chemical, none had been given adequate training on safety procedures and/or related health risks. The hospital failed to report K’s condition to the HSE until July 2000, 10 months after she became ill.

The hospital pleaded guilty and is now phasing out glutaraldehyde. Fines of £14 000 for failing to ensure the health and safety of employees were imposed, along with a £4000 fine for breach of Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations (RIDDOR) 1995 regulations for failing to report K’s condition plus £13 000 costs.

Trainees (i.e. student podiatrists on work experience or a placement)

Employers owe a greater duty of care to trainees and inexperienced workers. Inexperienced workers may well be regarded as recent graduates who may not necessarily have the work experience of more experienced employees. Thus the risk assessment for work practices may require additional arrangements for the safety of trainees, or recent graduates (inexperienced employees) as part of looking after each employee as an individual. Non-employed trainees (e.g. students on a work placement or potential students) may require special provisions and are entitled to the degree of protection given to ordinary employees by virtue of the Health and Safety (Training for Employment) Regulations 1990.

Health surveillance

Employers need to consider routine health surveillance, ensuring awareness of any employee disabilities. Health surveillance is a statutory requirement under the MHSWR when the following conditions are satisfied:

Obvious examples of known disabilities may also include dermatitis, previous back or neck injury and noise-induced deafness, etc.

It may also be prudent to consider pre-employment health questionnaires; these may be used to identify existing disabilities, enabling risk assessment to be related to the individual employee.

Visitors and the general public

Employers and practitioners have a duty to protect visitors (as non-employees) under Section 3 of the HASAW Act. The Occupiers’ Liability Act 1957 suggests that the employer can be liable for compensation to visitors injured on their premises. For guidance, visitors should not be left unaccompanied and they should not, if possible, be taken into hazardous areas of the practice. (It is prudent to ask visitors to sign in on arrival and sign out on departure and, ideally, be given basic instructions on what to do in the event of an emergency such as a fire.) If visitors are accompanied at all times, then in an emergency the practitioner could lead them to safety. Constant accompaniment also enhances security and prevents unnecessary accidents – it is a form of accident prevention.

Members of the public are also owed a duty of care, ensuring that they are not put at risk by the employer’s undertaking. The general duties of protection owed to visitors apply equally to the emergency services.

Trespassers

It is generally assumed the only duty owed to trespassers is that the occupier must not intentionally cause them injury. However, under the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1984, occupiers owe a duty to trespassers in respect of the state of their premises/practice and the activities undertaken if the following three conditions apply:

This does not require a practitioner to make the practice burglar-proof. However, adequate steps are required to ensure that there are no hidden, concealed or unexpected dangers on site. Warning notices or other steps to deter entry will be sufficient in most cases. Hence chemicals must be kept in a locked cupboard and clearly labelled.

HEALTH AND SAFETY POLICY

To assist the successful management of health and safety and fulfil statutory obligations, private practitioners should consider producing a health and safety policy. Where they employ five or more persons it is a legal requirement, but it is possibly best practice to have one even where fewer employees are employed. A health and safety policy must contain the following sections.

General statement of intent

This sets out the objectives of the health and safety at work that are applicable to and individualised to that practice. The general statement of intent may require updating on a regular basis as the objectives change. Suitable objectives will be those that include commitments to training, establishing reductions in accident rates (e.g. reducing the number of accidents with sharps; see Case Study 29.3). It may also include a standard to achieve in an externally audited system (e.g. Society of Chiropodists and Podiatrists Practice Accreditation scheme).

CASE STUDY 29.3 CHILD AT RISK FROM USED MEDICAL NEEDLES

An NHS Trust has been fined following an accident in which a child was put at risk by a container of used needles.

A large NHS Teaching Hospital Trust failed to ensure that sharps bins containing used needles and other sharp instruments were inaccessible to members of the public at one of their hospitals. A 21-month-old girl was waiting for her father in a corridor outside the maternity ward at the hospital. She put her hand into the sharps bin that had inadvertently been left hanging from a radiator. Her father then washed her hand in a sink. Hospital staff examined her and concluded that she had not suffered any puncture wounds.

The Trust failed to ensure that the sharps bin was stored in an area to which the public could not gain access. By leaving it in an unsupervised public area, the Trust had run the risk of injuring anyone who put their hand into the container. Incidents such as this could result in the contracting of diseases such as HIV or hepatitis B from used needles. The child would not have been put at risk if the sharps bin had been stored in an area away from where the general public had access.

The Trust pleaded guilty and deeply regretted the incident. Since the incident, it has commissioned independent health and safety audits to ensure that sharps bins are kept in locations where they cannot be accessed by members of the public and has produced posters to inform staff about the need to keep bins in a safe place.

The Trust was fined £3000 for a breach of Section 3(1) of the HASW for failing to ensure the health and safety of people not in employment, plus costs of £900.

Health and safety at work responsibilities

A range of health and safety responsibilities needs to be allocated in the health and safety policy. In private practice it is likely that responsibilities are with the practitioner, or that some are delegated to an external competent person.

Administration of health and safety at work

To comply with the MHSWR, a practitioner or employer must demonstrate arrangements for effective planning, organisation, control, audit and review of preventive and protective measures. The fulfilment of these items requires administration arrangements for the wide range of health and safety at work topics. These may include:

RISK ASSESSMENTS

Among a range of legislation, the prime example where risk assessment is required is under the MHSWR. These clearly require employers to undertake suitable and sufficient assessment of risks to health and safety arising from work activities. The range of legally required risk assessments undertaken by the practice are consolidated in the health and safety policy, or at minimum cross-referenced with the policy statement.

The exact arrangements for undertaking risk assessments are outlined in the administration of health and safety at work section, while responsibility for undertaking and recording them is contained in the responsibilities section of the health and safety policy. The actual undertaking of a risk assessment should not be seen as the end of the process – it is the beginning. It is the means of identifying steps to ensure the control of health and safety risks. Health and safety at work record-keeping requirements can arise in relation to a very wide range of issues.

Record-keeping requirements

Practitioners need to identify the exact record-keeping requirements appropriate for their individual practice. These are just some examples and it is possible that the full list of record-keeping requirements could be greater.

Safe systems of work

Related to suitable and sufficient risk assessments is the need to establish and monitor safe systems of work. The range of safety procedures and safe systems of work established may include written schemes of work for waste-disposal arrangements, sterilisation and cross-infection procedures to safeguard against hepatitis and human immunodeficiencey virus (HIV), and working alone. This may be by a poster or notice at the decontamination area stating what the procedure is in the manner of a recipe (i.e. step 1, step 2, etc.).

It is important that any working system and procedures established for employees is understood by any contractors (e.g. locums) employed for similar work in the practice. The practice manager/senior partner or practitioner should ensure that locums or students follow the practice policies and procedures when undertaking practice on their site.

Accident procedures

The Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations 1995 (RIDDOR 1995) set out the legal obligations for reporting accidents and dangerous occurrences to the enforcing authority. It is each practitioner’s responsibility to ensure these legal obligations are met.

The responsible practitioner should establish a clear policy in all aspects of accident and ill-health procedures, including suitable first-aid arrangements and control of health hazards such as dust. Podiatrists should ensure that musculoskeletal problems causing them to be off work for longer than 3 days are reported under RIDDOR.

Working environment

The Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations 1992 are concerned with good housekeeping standards and safe storage of goods. In addition, they specify extensive standards relating to the working environment, covering such factors as ergonomic considerations and compliance with the Health and Safety (Display Screen Equipment) Regulations 1992 (as amended 2002). These regulations apply to most places of work and establish strict controls on the working environment in which display screen equipment is used.

Control of chemicals

The Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations 2002 (COSHH) require detailed risk assessment. The practitioner needs to ensure adequate attention is paid to these and, in particular, the following:

Fire safety

Recent legislation (The Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005) altered the main approach, which is again based on risk assessment with the principle of prevention being applied. In terms of control, adequate storage of flammable and explosive materials is required. There are a number of potential substances within podiatry that fall under these headings. When fire hazards and risks are suitably controlled, then other areas, which might require attention, are:

Physical agents/stored energy

The main types of physical agents and stored energy of interest to the podiatrist are possibly:

In all cases, there is much legislation regulating these hazards.

Plant and equipment

There is a whole range of work equipment present in the podiatric practice, and the practice itself may require review to ensure compliance with the Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations 1992 and other appropriate legal standards.

The practitioner should keep a full register of work equipment with routine inspections as necessary. Arrangements for purchasing new equipment and for hiring/leasing equipment should be scrutinised, and all work equipment should be properly stored and maintained. The Provision and Use of Work Equipment Regulations 1998 (PUWER) provide a framework for the continued adequate and safe use of tools and machinery.

Handling operations

Safe use of lifting machinery (e.g. hoists for patients), arrangements for safe manual handling (equipment and patients) and safety in storage areas are all major safety concerns. Although podiatrists do not manually handle patients in a manner such as physiotherapists do, they still need to be aware of good posture, movement, ergonomic design of workplaces, and lifting or manual handling of equipment (e.g. domiciliary cases, stools, drills).

Risk assessment

The objective of a health and safety risk assessment is to identify or quantify the extent of risk of any activity/process/material and from that information implement measures to control or reduce the risk attached to it. An understanding of the principles and techniques of risk assessment will enable decisions to be taken about priorities in the management of risk.

Risk assessments should be ‘suitable and sufficient’ and must be carried out by a ‘competent person’. This should allow the business to determine any measures required to allow compliance with relevant health and safety legislation. Where there are five or more employees, these risk assessments should be documented. However, it is prudent for all assessments to be documented, enabling practitioners to have proof that such an assessment was carried out.

Practitioners should regard a risk assessment as a ‘reasoned judgement about the risks and extent of these risks to people’s health and safety, based on the common sense application of information, which lead to decisions about how risks should be managed’. The process of risk assessment is one commonly utilised by podiatrists within normal routine practice. It is a process of reasoning skills, ending with a justifiable action plan for safety measures, which will eliminate or, at worst, minimise the risk of harm to people by the actions, operations, products or services of a podiatric practice.

Principles of risk assessment

There is a need to define certain terms used in risk assessments. A hazard is defined as something with the potential to cause harm or injury. For example, a nail drill is a hazard in that it has the potential to cause harm either by the fact that electricity powers its actions, or that if it were to drop onto an unprotected toe the toe could be damaged. Risk is then defined as the likelihood of harm or injury resulting from the hazard. Thus, if the nail drill is checked regularly for electrical safety then the likelihood of someone coming to harm from an electrical shock is small. If the drill is not moved about unnecessarily and is on a stable base, then the likelihood of it falling and dropping onto a toe is small also. The extent of the risk is the number of people who might be exposed and the consequences for them. To keep the example going, the extent of the risk is that either one or two people might be affected – the operator and possibly the patient. The consequences might be severe in that in the worst case electrical shock might result in death.

Risk assessment is an extension of techniques employed by podiatrists in their daily activities. Podiatrists are used to employing clinical reasoning skills, using problem-solving and decision-making techniques to conduct examination and assessments of patients. Health and safety risk assessments employ similar techniques.

Problem-solving and decision-making

The primary principles of risk assessment are problem-solving and decision-making and risk evaluation and control techniques. The key principles are the same as those for determining solutions to any problem, such as diagnosis of a patient’s signs and symptoms:

Thus, the principles employ techniques similar to those used by podiatrists in practice. These are:

However, in terms of health and safety, the variety of interests might go further than in podiatric practice where the interests served include those of the individuals concerned:

The problems to be addressed are the health and safety risks, with solutions being the measures designed to control or reduce the risks. The relevant people are those able to assess the risks – the practitioner or a delegated competent person; those who come into contact with the risks every day and know what can happen in practice; and those who need to invest time, money, consideration, effort or other resources to implement the measures decided upon. In all these cases the relevant person is the practitioner.

Evaluation and expression of risk

These principles of risk assessment are found in the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) publication HS (G) 65: Successful Health and Safety Management, and in the Approved Code of Practice to the MHSWR.

The likelihood of any hazard causing harm depends on a number of factors:

Residual risk

Once the practitioner has detailed all the relevant factors, an informed judgement is required. This leads to a decision on the likelihood of harm being caused by the hazard in particular processes, events or circumstances. The risk that results should also have taken into account existing controls – in some texts what is left is referred to as the ‘residual risk’.

Expressions to identify risk

It is difficult to give explicit information about how to undertake a risk assessment as there are no principles or standards, apart from those of language and communication, which determine how the harm, which might result, should be expressed to a third party. In cases of quantified risk assessments the principles of mathematics and statistics can apply. In some cases a numerical probability (quantitative assessment) can be designed after research, while in others a qualitative assessment is all that will transpire. Thus, in terms of a risk assessment regarding nail dust, it might be feasible to say ‘it is dangerous to use a nail drill which has not been maintained’ thus indicating a higher level of risk than ‘it is reasonably safe to use a nail drill which has been maintained’. Similarly, ‘there is a high risk of being hit by a shard of nail particle if eye protection is not worn’ indicates a higher level of risk than the expression ‘there is a low risk of being hit by a shard of nail if eye protection is worn’. Other means to convey the same relativity of risk include: ‘Eye protection not worn – risk from dust particles in the eye = 7; risk from dust particles if eye protection worn = 3’; and, if a quantified assessment has been made: ‘chance of being injured when wearing eye protection = 1 in 26 156; chance of being injured when not wearing eye protection = 1 in10 763’. These figures are exemplars only and are not based on research, and therefore should not be used as definite figures.

The severity of the harm may be an additional factor to be taken into account when evaluating risks. Thus it is essential that a competent person use a means of expressing risk and its extent to facilitate:

As in podiatric practice a systematic approach to the process is useful, and provides some assurance that the decision is liable to be meaningful and consistent.

Principles for risk control

The aim of risk assessment is to reduce or control risk. The ACOP (Approved Code of Practice) states employers should apply the following principles when deciding measures to control risks:

It is good practice to reduce the risk by combating it at source if it cannot be eliminated or avoided altogether. Reliance on palliative measures (e.g. warnings, safe working procedures and personal protective equipment) is poor practice to reduce the severity of harm from the hazard or likelihood of exposure to the hazard.

Basis for assessment

The primary basis of any technique for risk assessment is an examination of two questions:

Any technique for risk assessment needs to communicate the answers to these two questions.

Five steps to risk assessment

Step 1. Look for hazards

Walk around the practice identifying what reasonably could cause harm. Ignore trivial items and concentrate on significant hazards that might result in serious harm or affect several people. Ask others what they think. If you employ others, ask them and solicit views and opinions. Manufacturers’ instructions and safety data sheets can help, as can the accident and illness records of any staff.

Step 2. Decide who might be harmed, and how

Identify others who might use the premises, but may not be in contact with the hazard all the time (e.g. patients, carers, cleaners, contractors).

Step 3. Evaluate the risks from the hazards and decide whether existing precautions are adequate or whether more is required

For the remaining hazards decide whether the risk is high, medium or low (see Figure 29.1). Ask whether you have done all that the law requires. Find out whether there are standards of clinical practice or guidelines advised by the professional body. The law requires that a practitioner must do what is reasonably practicable to keep the practice safe. The overall aim is to make all risks small by means of additional precautions. If a hazard is identified ask: Can the hazard be removed altogether? If not, how best are the risks controlled? Personal protective equipment is a last resort when there is nothing else that can reasonably be done to reduce the risk. Select hazards that can reasonably be foreseen and assess the risks arising from those hazards (see Case Study 29.4).

CASE STUDY 29.4 AN EXAMPLE OF A COSHH ASSESSMENT COMPLETED FOR DUST

Nail dust is identified as a possible hazard that might result in occupational asthma, rhinitis or eye problems. It is a medium risk, and the following controls should be investigated:

Date of assessment: October 2004; review: October 2005. Health surveillance required of dust monitoring samples: settle plates and air sampler, respiratory tests on staff, lung function capacity.

Step 4. Record findings

Where there are five or more employees, the employer must record the assessment and the conclusions reached, as well as the plan of action to be adopted for reducing or controlling risks. The assessment required is that of suitable and sufficient, not perfect. According to the Trades Union Congress (TUC) the real points are: Are the precautions reasonable and is there something to show that a proper check was made?

Step 5. Review assessments on a regular basis and revise when necessary

In practice, changes occur over time, and they require a corresponding change in control measures. For example, there may be a change in the design of nail nippers, which may reduce the risk of RSI. This may require a change in the risk assessment of working practice and a safe system of work for reducing toenails. Date the risk assessments, and also suggest a date for review on your records.

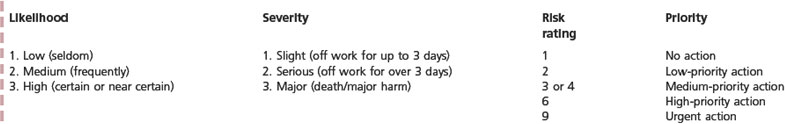

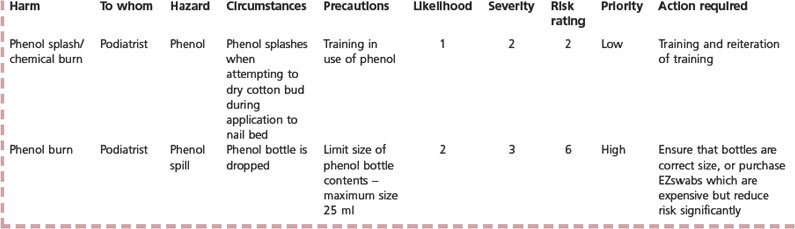

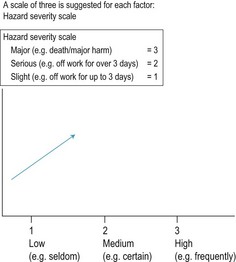

Using risk factors to evaluate risk

A technique is required to evaluate the risk and quantify the risk. The HSE publication HSG65 Successful Health and Safety Management suggests that the assessment of risk involves rating two factors affecting the risk:

Likelihood of occurrence rating

Risk can be calculated by multiplying the severity factor by the likelihood factor and expressing it as a number showing the significance of the risk compared with other risks. For example, the almost certain likelihood (3) of serious injuries (2) from a given hazard (3 × 2 = 6) would be demonstrated by a number as a more significant risk than an unlikely (1) fatality (3) resulting from another hazard (1 × 3 = 3). This value is termed the ‘risk rating’ (Table 29.1). It is a number (1, 2, 3, 4, 6 or 9) providing a working value of the residual risk, which helps to complete the answer to the question of what could go wrong.

Table 29.1 The risk rating = likelihood × severity

| Likelihood of occurrence (i.e. probability) | Hazard severity (consequence) | Risk rating |

|---|---|---|

| 3 = High | 3 = Major | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 or 9 |

| 2 = Medium | 2 = Serious | |

| 1 = Low | 1 = Slight |

Expressing priorities for risk control

The assessment is not, however, seen as complete if it remains as only a statement of hazards and risks. It must contain conclusions about the action needed to eliminate or reduce the risk. The risk assessment therefore needs another stage beyond the evaluation of the risk. This is the step that identifies the action required (i.e. measures in addition to existing precautions, necessary to control the risk). Also, it is helpful to include a priority term, specifying the immediacy of action.

| Risk rating | Priority |

|---|---|

| 1 | no action or low priority |

| 2 | low-priority action |

| 3 or 4 | medium-priority action |

| 5 | high-priority action |

| 6 | urgent action |

A key issue in managing a risk ‘insofar as is reasonably practicable’ is that the employer must establish the limits of reasonable practicability.

Limits of reasonable practicability

To establish the limits of reasonable practicability the employer (the competent person(s) appointed by the employer under MHSWR) must decide on effective control measures, having balanced the degree of risk against the cost (money, time and trouble) of eliminating or minimising risk. A risk assessment may well result in a cost–risk analysis, establishing which of various proposed control options is the most cost-effective.

So far as is practicable

There are a few circumstances where practitioners will need to go beyond the minimum standards set by specific regulations or the limits of reasonable practicability. This is where subordinate legislation imposes a requirement qualified by the term ‘so far as is practicable’. This implies that the most effective risk control that is technically feasible needs to be used, irrespective of the cost and inconvenience to the practitioner.

Refinement of risk factors to help apply control principles

Factors affecting risk also assist in determining effective control measures. For example, when assessing the risk of podiatrists contracting HIV from a known AIDS patient the risk may be regarded as:

| Hazard | Risk |

|---|---|

| HIV | Serious |

However, the addition of the two factors ‘hazard severity’ and ‘likelihood of occurrence’ allows the judgement to be improved and to guide additional controls that might be more effective.

| Likelihood | Hazard severity | Risk |

|---|---|---|

| 2 (medium) | 3 (major) | 6 |

In this example it may not be possible to reduce the severity of the hazard, but a particular measure (good handwashing technique and disposable gloves) may reduce the likelihood of an occurrence from 2 (medium) to 1 (low), thereby reducing the overall risk.

Generic risk assessments

Generic risk assessments are termed ‘model’ assessments. These are designed to cover more than one work practice (e.g. a Trust may use a generic risk assessment for all podiatry clinics) in which the risks associated with particular types of workplace, work activity, plant and substance, etc. may be common.

However, caution is needed with these models. If an assessment made for one clinical facility is to be used elsewhere, whether or not the employer is in control of both sites, the employer needs to review and evaluate that assessment, making any necessary revisions to ensure that the assessment is suitable and sufficient for all the circumstances in which it is to be used. Thus the position of an employer, for example a Trust which makes model assessments for use by all its podiatry clinics, is exactly the same as that of a single-site employer who acquires copies of assessments made by a similar enterprise or recommended by a trade association or commercial publisher, etc. However, as employees differ, a generic risk assessment may have problems. For example, in the case of manual handling, generic risk assessment should be avoided as the load may be the same (i.e. domiciliary bag and content) but the individual capacity may well vary between males and females and also between individuals, which would require assessment.

Practitioners should not accept generic risk assessments without ensuring that they are suitable for the premises to which they will apply. Therefore, all generic assessments should be assessed and any necessary modifications made to adapt them to the circumstances or clinics in which they are to be used. While there are disadvantages to using generic assessments, if drawn up by competent, knowledgeable persons they may have benefits. An appropriate generic assessment can save considerable time: managers at a site can start with a generic form that includes information about hazards, risks and precautions, which they can review and make any changes needed to render it suitable and sufficient. However, an inappropriate or poorly designed generic assessment can also waste time: practitioners may waste time understanding the form and the relevance of the information in a model assessment.

LEGAL REQUIREMENTS WHERE RISK ASSESSMENT IS SPECIFIED – SPECIFIC RISKS

Noise at Work Regulations 2005

The level at which employers must provide hearing protection and hearing protection zones is 85 decibels (dB) (daily or weekly average exposure) and the level at which employers must assess the risk to workers’ health and provide them with information and training is 80 dB. There is also an exposure limit of 87 dB, taking account of any reduction in exposure provided by hearing protection, above which workers must not be exposed.

This is potentially a problem where orthoses are manufactured, depending on the type of equipment used for grinding and buffing, as well as the size of the room and the acoustics within the room.

Health and Safety (Display Screen Equipment) Regulations 1992 (as amended 2002)

Employers and practitioners need to assess the risks of musculoskeletal injury, visual problems and mental stress from the use of display screen equipment. This is much more likely nowadays with the use of PC-based patient record systems and computerised gait analysis systems.

Manual Handling Operations Regulations 1992 (as amended 2002)

This area is poorly assessed within podiatry. Assessment of hazardous manual handling tasks must be undertaken, considering the interaction of the following factors: the task, the load, the working environment, the individual’s capacity and any other factors. Podiatry is an occupation requiring a lot of awkward bending, rotating and lifting movements. It may not require handling of patients as is required in physiotherapy but the posture of individuals is regularly compromised by the design and set-up of the working environment.

Personal Protective Equipment at Work Regulations 1992 (as amended 2005)

Prior to selecting personal protective equipment, employers must assess whether it is suitable, both for the nature of the hazard and for the prospective user. Facemasks have been used for a number of years when a nail drill is used. However, these are frequently inappropriate for the task, do not meet the required standard for nuisance dust and are ineffective. Similarly, eye protection is required for the aforementioned work activity and requires an individual assessment to ensure suitability of the protection for the individual practitioner due to various facial characteristics.

Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations 2002

These regulations are very important within the podiatry context. Each medicament requires an assessment of the risks to employees/practitioners through the use of and exposure to the wide range of substances or hazardous agents used or generated in the practice of podiatry. The manufacture of orthoses, the treatment regimens for verrucae and routine podiatric practice all involve the use of substances hazardous to health. The assessment must, however, relate to the system of work that the practitioner adopts.

Management of Health and Safety at Work (Amendment) Regulations 1999

Employers are required to assess the risks to the health and safety of pregnant workers, those who have recently given birth and those who are breastfeeding, to ensure that the health and safety of these employees is not put at risk. If a risk remains, and it is not possible to remove it, employers should consider changing the employee’s conditions of work or hours, or offer alternative work.

The Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005

This requires an assessment of the fire risks in the premises along with appropriate emergency plans. The plans need to ensure adequate detection and warning methods in addition to suitable fire-fighting equipment. All those on the premises must be able to get out safely.

Health and Safety (First Aid) Regulations 1981

The Approved Code of Practice (L 74) places responsibility on the employer to make an evaluation of the first aid requirements and provide necessary resources to meet the assessed need. Thus, a practitioner must assess the requirements for a first aid box and the amount of training needed, as well as decide on the number of trained first aiders required for their premises.

For the various Regulations and aspects of the HASAW and MHSAW that may apply in podiatric practice, see the Society of Chiropodists and Podiatrists website: http://www.feetforlife.org.