Chapter 13 Female Genital System and Breast

Female Genital Tract – Anatomy and Physiology

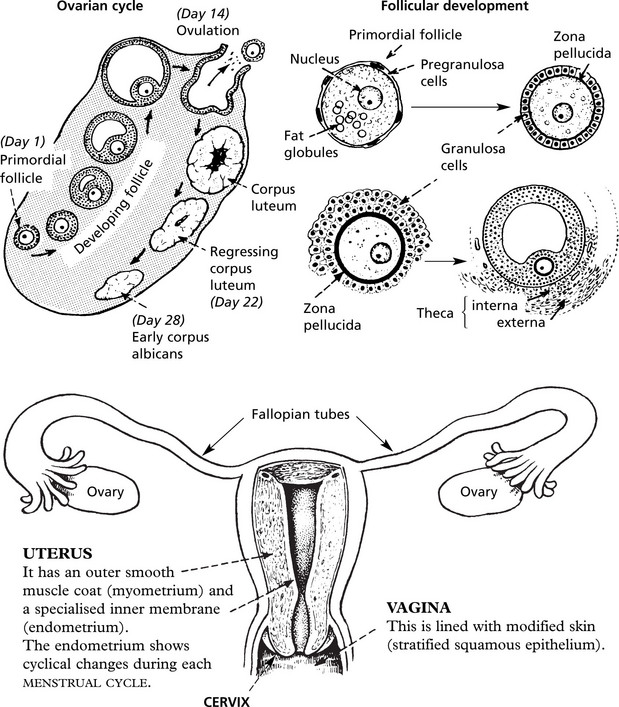

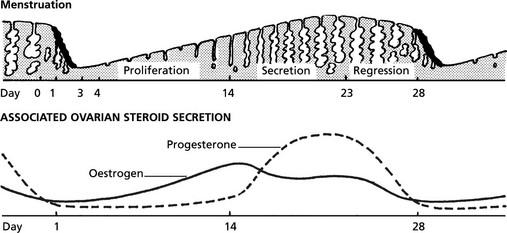

The following diagrams summarise normal anatomy and physiology:

Cyclical Endometrial Changes

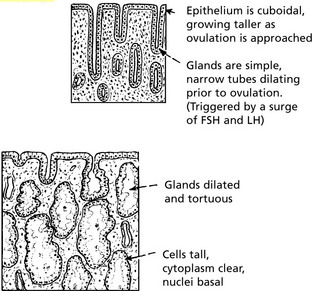

Proliferative Phase

This is induced by oestrogen produced by developing ovarian follicles, stimulated by FSH from the pituitary.

Diseases of the Endometrium

Acute infection is nearly always associated with childbirth and abortion – often related to retention of products of conception. Historically, criminal abortion in non-sterile conditions led to severe infection. Gonococcal infection does not commonly extend beyond the cervix but can lead to acute endometritis. Chlamydia may cause acute or chronic endometritis.

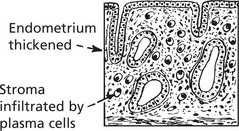

Chronic Endometritis

This can be seen in chronic pelvic inflammatory disease and in relation to retained products of conception.

Tuberculous Endometritis

This is now uncommon in UK. It is the result of infection spreading from the fallopian tubes. If the patient is still menstruating, the tubercles are shed each month: diagnostic biopsy should be done as late in the cycle as possible to allow new tubercles to develop. In some cases, menstruation ceases and caseation occurs.

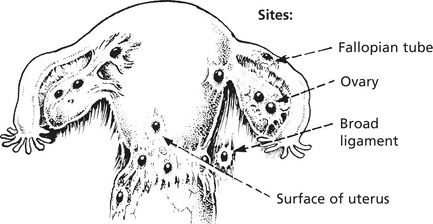

Endometriosis

This consists of deposits of endometrium outside the uterine cavity.

In most cases, the disease is confined to the pelvis and the genital tract.

Other sites: Caecum and appendix, bladder, rectum, umbilicus laparotomy scar.

These deposits show cyclical changes. The result is haemorrhage into the local tissues at the time of menstruation. Adhesions develop, often leading to infertility. Malignant change to endometrioid adenocarcinoma occurs uncommonly.

Adenomyosis

Deep down growths of endometrium occur within the myometrium. There is an accompanying overgrowth of muscle and connective tissue. Two macroscopic forms occur:

Deposits are confined to inner part of myometrium. Foci of endometrium often brownish in colour

The endometrial deposits communicate with the uterine cavity, but despite this they often contain altered blood in the glands which become cystic. The diffuse type is commoner. Adenomyosis is not related to endometriosis.

Endometrial Hyperplasia

Endometrial hyperplasia occurs in 3 forms: Simple hyperplasia, complex hyperplasia and atypical hyperplasia. Of these, atypical hyperplasia is most important as it is associated with an increased risk of malignancy. Progressive molecular genetic alterations occur on the pathway to cancer.

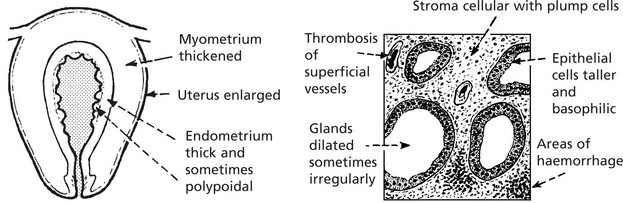

Simple Hyperplasia

This tends to occur in the peri-menopausal period. It is due to excess oestrogen stimulation – particularly associated with anovulatory cycles, but rarely with oestrogen therapy or oestrogen-secreting tumours.

Clinically, there is irregular, frequent and heavy bleeding.

Complex Hyperplasia

In this form, hyperplasia is often focal and glands but not stroma are affected. Thus the glands appear crowded, but show no atypia. There is no increased risk of malignancy.

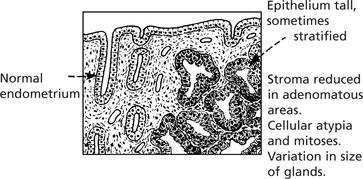

Atypical Hyperplasia

In this condition the hyperplasia is focal and cytological atypia with mitotic figures is common. Intervening endometrium may show simple hyperplasia. The importance of atypical hyperplasia is its relationship to the development of adenocarcinoma, i.e. it is considered to be pre-cancerous. Up to 40% have co-existing carcinoma in hysterectomy specimens.

Endometrial Carcinoma

This common gynaecological cancer particularly affects postmenopausal patients, who typically present with vaginal bleeding.

Carcinoma

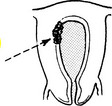

This growth may form a localised plaque or polyp.

In some cases it appears as a diffuse change involving much of the endometrium. It grows initially within the endometrial layer, bulging into the uterine cavity.

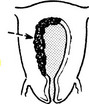

Most growths are well-differentiated adenocarcinomas (endometrioid). These are graded from I - III

In some cases with a particularly poor prognosis malignant squamous epithelium is admixed with the adenocarcinoma – so-called adenosquamous carcinoma.

The endometrium possesses no lymphatics and invasion of the myometrium takes place slowly.

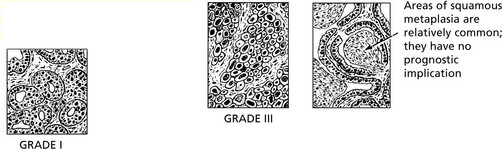

Local extension: this may take place in several directions.

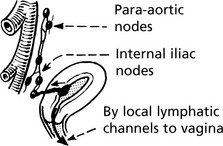

Metastases

The most important prognostic factor is the stage of the tumour, usually expressed in the FIGO (International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics system).

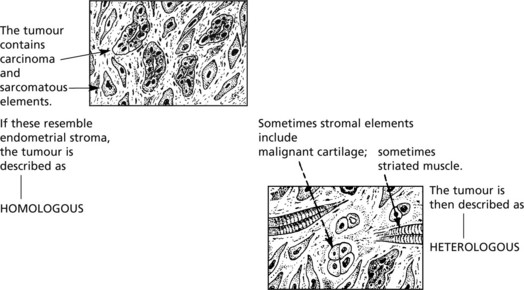

Endometrial Stromal Sarcomas

These rare tumours may be of low grade or high grade.

Low grade tumours – infiltrate extensively through the lymphatics of the myometrium. The cells are cytologically bland and mitoses are few. About one fifth of patients eventually die from the disease.

High grade stromal sarcomas – are highly malignant spindle celled tumours, with poor prognosis. It may be difficult to separate these from uterine leiomyosarcomas.

Diseases of the Myometrium

Tumours of the myometrium are extremely common.

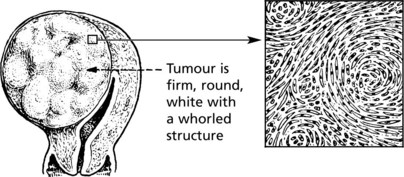

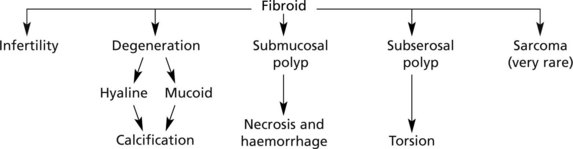

Leiomyoma (Fibroid)

This is a circumscribed growth derived from uterine muscle.

The cells are typical long spindle muscle cells, arranged in interlacing bundles

They vary in size from tiny (mm) growths to several cm in diameter and are frequently multiple.

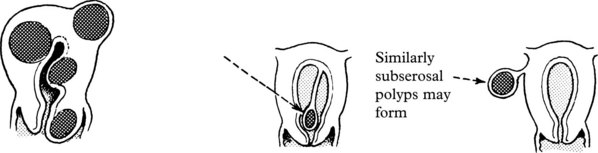

Fibroids may be found in any part of the uterus.

Tumours beneath the endometrium tend to bulge into the cavity and may eventually develop to form a fibroid polyp.

Diseases of the Cervix

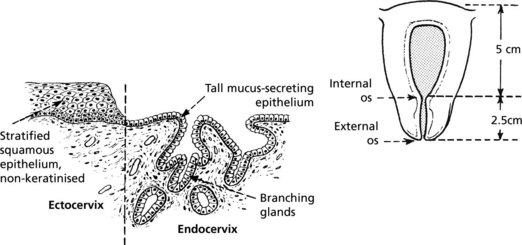

The cervix constitutes the lower one third of the uterine body.

It is in two parts: endocervical and ectocervical with different lining epithelium.

The remainder of the cervical wall consists of circular smooth muscle lying in abundant fibroelastic tissue.

At the internal os, the structure gradually merges with that of the uterus proper, the branching glands giving place to the simple tubules of the endometrium, and the proportion of muscle increases greatly.

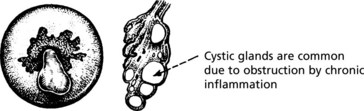

Cervicitis

Inflammation of the cervix may be acute or chronic. Acute cervicitis may be due to gonorrhoea or follow cervical laceration at childbirth.

Chronic cervicitis is commoner and may be due to candida, trichomonas (p.506) and chlamydia. The last is associated with reactive lymphoid follicles (follicular cervicitis).

Viral infections of the cervix include Herpes Simplex Virus (Type II) and human papilloma viruses (HPV). The latter can cause simple viral warts or be associated with cervical intraepithelial dysplasia and neoplasia (CIN) and invasive carcinoma (p.504).

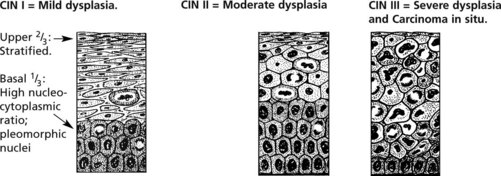

Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN)

The Transformation Zone

From puberty onwards and particularly in pregnancy the squamo-columnar junction presents on the vaginal surface of the external os. This is the area where squamous metaplasia occurs. It is important because cervical squamous carcinoma and its precursor cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) begin there. Within this metaplastic epithelium, dysplastic changes may develop. They are graded as CIN I, II and III. Later, in some cases, invasive squamous carcinoma develops.

Koilocytes (cells with a wrinkled pyknotic nucleus and perinuclear cytoplasmic clearing) are often seen in the suprabasal layers and indicate HPV infection.

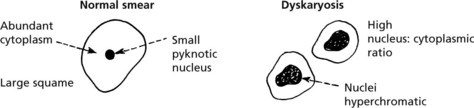

Cytology and CIN

The cervical screening programme aims to detect CIN and thus prevent the development of invasive carcinoma. Cellular preparations from the squamo-columnar junction obtained by a cervical brush are stained by Papanicolaou’s method (liquid-based cytology). The cells can be examined for dysplasia – so-called dyskaryosis. Inflammatory changes, e.g. due to candida infection, may be seen.

The cytology is a screening test. Patients with abnormalities are referred for colposcopy where abnormal epithelium turns white on exposure to acetic acid (acetowhite). Punch biopsy to diagnose dysplasia is followed by laser ablation (laser loop excision of transformation zone). New techniques to identify proliferating and malignant cells are being rapidly developed.

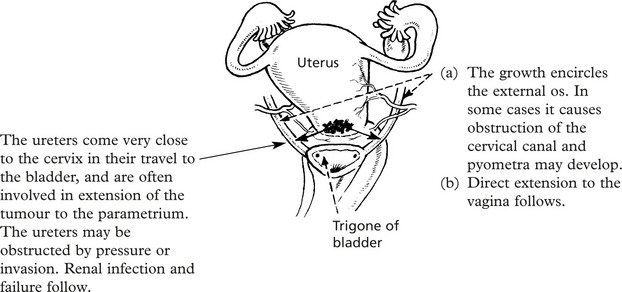

Carcinoma of Cervix

Carcinoma

This is the most common malignant tumour of the female genital tract, even where there is a vigorous screening campaign for early diagnosis and eradication of dysplasia. The tumour is a squamous carcinoma in 90% of cases, and an adenocarcinoma in 10%. Most squamous carcinomas arise at the squamo-columnar junction: most adenocarcinomas arise within the endocervical canal.

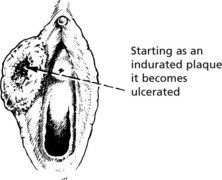

The cervix becomes indurated with necrosis and ulceration

Later, a large fungating mass is produced

Microinvasive carcinoma is the earliest stage of invasive cancer – where spread is less than 5 mm in depth. This is associated with an excellent prognosis.

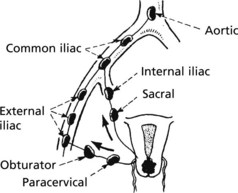

Spread

Until a very late stage, the disease is confined to the pelvic cavity. The patient commonly dies before distant metastases appear.

Prognosis

With modern treatment there is an 80% 5-year cure rate when the disease is diagnosed early, i.e. confined to the cervix: it falls significantly if spread to the pelvis has occurred.

Previously death was commonly due to a combination of renal failure and sepsis: fatal haemorrhage from eroded vessels also occurred. With better local control death is usually due to metastases.

Diseases of Vagina and Vulva

Vaginal discharge is a common complaint especially in parous women. In many cases it is related to chronic cervicitis. There are however a number of inflammatory conditions which arise primarily in the vagina.

Gonococcal infection may produce an acute inflammation with purulent discharge but it is often asymptomatic.

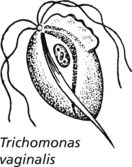

Purulent discharge is also associated with infection by a protozoon, Trichomonas vaginalis. The discharge tends to be frothy. It is commonly transmitted during sexual intercourse. The male can also be infected.

Candida albicans infection is common in pregnancy, in diabetes and in patients undergoing antibiotic or immunosuppressive therapy.

PRIMARY TUMOURS of the VAGINA are rare. Squamous carcinoma occurs in the upper vagina of women and may lead to fistula formation between the vagina and the bladder or rectum. Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) may be associated with CIN and VIN. Historically, clear cell carcinoma was sometimes found in adolescent girls, due to the effect on the fetus of administration of diethylstilbestrol to the patient’s mother during early pregnancy. It arose in a background of vaginal adenosis – a proliferation of glands within the vaginal wall.

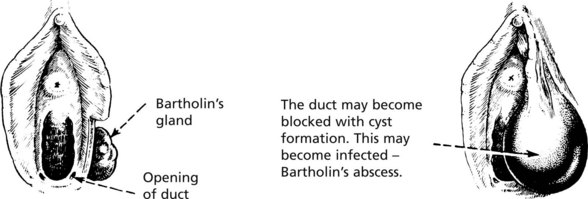

VULVAL INFLAMMATION is common in post-menopausal women. It is related to atrophy of the skin, which has very thin epithelial covering at this phase of life and is easily abraded. Inflammation at other periods of life frequently involves Bartholin’s gland.

Two conditions which mainly occur in the tropics and are seen only very occasionally in temperate countries are:

Leukoplakia and Premalignancy

Leukoplakia is a descriptive term meaning white patches. These are common on the vulval and perineal region in almost any chronic inflammatory skin condition due to the local moist conditions, e.g. chronic dermatitis (lichen simplex), fungal infection and lichen sclerosis.

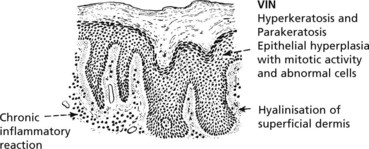

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) presents as white patches which show varying degrees of dysplasia. It is premalignant.

The degree of dysplasia varies, amounting to carcinoma in situ in some cases.

These changes are now numerically graded VIN I, II and III, i.e. Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia (analogous to CIN).

Tumours of the Vulva

Benign tumours are common. condylomata acuminata are papillomas due to infection by Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) types 6 or 11. Koilocytosis (see p.503) in the superficial keratinocytes is characteristic.

Diseases of the Fallopian Tube

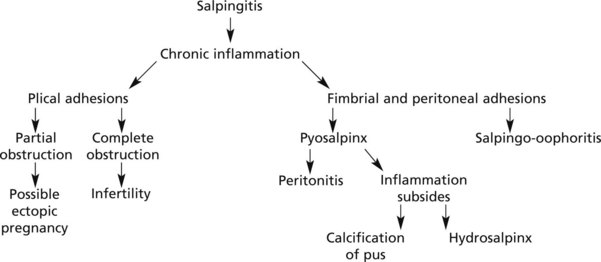

Acute Salpingitis

This is the result of ascending infection from the endometrium: some cases follow abortion and puerperal infection. Chlamydia may cause acute salpingitis.

The inflammation is usually bilateral and primarily involves the tubal plicae which are congested and oedematous; with a purulent exudate.

If resolution of the acute inflammation does not occur (antibiotic therapy is important) chronic salpingitis follows. The term ‘pelvic inflammatory disease’ is used.

Tuberculous Salpingitis

Tuberculous infection of the female genital tract, for some unexplained reason, almost always starts in the fallopian tube. It is usually due to blood spread from some other site: only very occasionally it is secondary to tuberculous peritonitis.

The complications are those expected of a chronic salpingitis with the added element of caseation.

Tumours of the Fallopian Tube

Benign tumours such as fibroma and myoma occasionally occur. Small cysts of congenital origin are common around the fimbrial ends of the tubes.

Carcinoma, usually a papillary adenocarcinoma, is extremely rare. There may be a profuse watery secretion which appears as a vaginal discharge. There is an association with BRCA mutations.

Diseases of the Ovaries

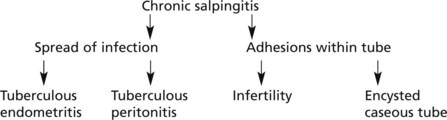

Oophoritis

Inflammation of the ovaries is always secondary to disease of the fallopian tubes or peritoneum. The inflamed fimbrial end of the tube becomes adherent to the ovary and direct spread of infection occurs. Tubo-ovarian inflammation is also associated with the presence of an intra-uterine contraceptive device (see p.496). Important local complications may follow.

The ovary may be similarly involved in tuberculous salpingitis, and caseating lesions can occur.

Ovarian Changes of Functional Origin

The control mechanisms of ovarian function frequently develop faults resulting in abnormalities of structure:

Follicular Cysts

These may be single or multiple. The maximum diameter of a normal Graafian follicle is 1.5–2 cm. Single follicular cysts may be several centimetres in diameter.

Bilateral, multiple small cysts of this nature occur in polycystic ovarian disease and are associated with obesity, hirsutism and oligomenorrhoea (Stein-Leventhal syndrome, polycystic ovary syndrome).

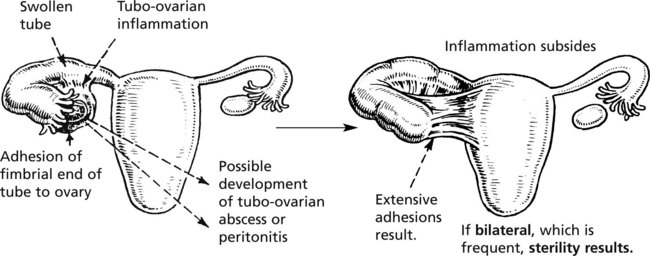

Theca Lutein Cysts

These are cysts from which the granulosa cells have disappeared, leaving cysts surrounded by luteinised thecal tissue.

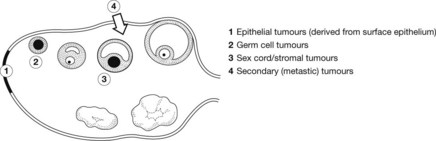

Many types of ovarian tumours exist. Various classifications have been suggested; none is completely satisfactory. The following is a simple working classification:

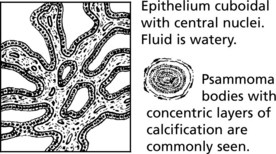

Common Epithelial Tumours

These comprise 70% of all ovarian tumours and 90% of malignant tumours and are found in adult life, very rarely in children.

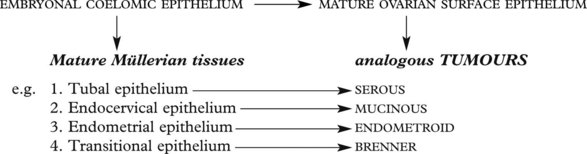

Histogenesis: The ovarian surface epithelium and the various mature Müllerian structures have a common origin in embryonal coelomic epithelium. The ovarian surface epithelial stem cells retain the ability to differentiate along different pathways: this explains the histological appearance of these tumours.

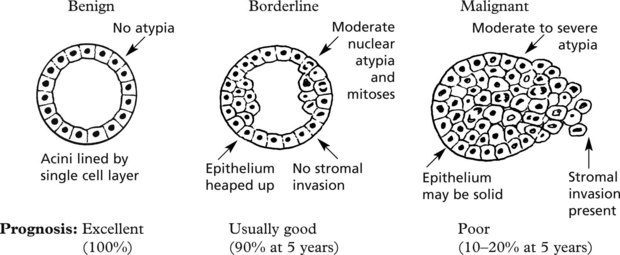

The histological features relate to a spectrum of behaviour:

Common Epithelial Ovarian Tumours

Complications

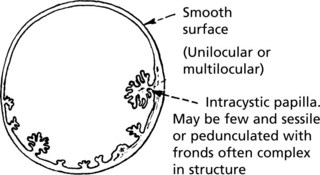

This is the commonest malignant tumour of the ovary – responsible for 40% of the total. Usually it takes the form of exuberant papillomatous growths extending over the surface and obliterating the ovarian structure. It is often bilateral.

Carcinoma of the Ovary

Complications

Congestion, often infarction due to interruption of blood flow

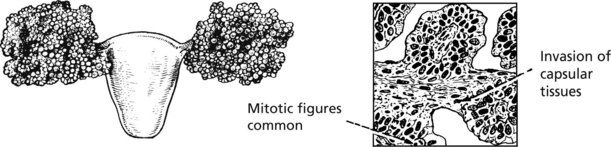

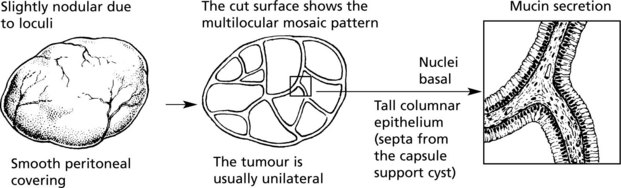

This accounts for 20% of all cases of primary carcinoma of the ovary. It almost always arises as a malignant transformation of a benign cystadenoma.

Areas of solid growth appear in the cyst wall.

Frequently in the malignant areas, florid papillary structures are formed and where the change is widespread it may be difficult to differentiate it from the malignant form of papillary cystadenoma.

In a considerable number of cases, ovarian carcinoma has a solid or semi-solid appearance and as such starts off as a growth smaller than either of the cystic tumours.

Microscopically, these show differentiation towards an endometrial pattern and are termed ‘endometrioid’. Some cases arise in endometriosis. Endometrioid adenofibroma is the benign equivalent.

Progress in Ovarian Carcinoma

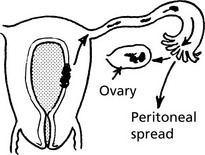

Spread of ovarian cancer in the early stages is by direct extension to the pelvic peritoneum. The papillary serous cancer seeds widely in the peritoneal cavity and only later are lymphatics invaded and metastases appear.

The mucinous variety rarely spreads by lymphatics.

The overall 5-year survival rate for ovarian cancer is only 30% and death often takes place within 2–3 years due to cachexia and interference with intestinal and renal function.

Tumours of the Ovary – Sex Cord Stromal

These may be divided into two broad groups:

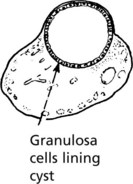

Granulosa Cell Tumour

This is composed of cells resembling the granulosa cells lining Graafian follicles. They vary in size from a few mm to large cystic structures. Commonly, the smaller varieties are found deep in the ovarian substance. This tumour may be found at any age: 5% occur in children; 50% in the child-bearing years; 40% postmenopausally.

Rosettes of cells with nuclei radially arranged are common (Call-Exner bodies)

All granulosa cell tumours are potentially malignant – they may recur, sometimes many years after removal.

Measurement of serum inhibin (a glycoprotein produced by granulosa cells) is useful in following progress.

Thecoma

This is a spindle-celled tumour, found mainly during the 3rd, 4th and 5th decades of life. It is benign and rarely recurs.

Function of these tumours varies widely. Oestrogenic effects consist of:

Fibromas are histologically similar but do not produce hormones. They may be associated with pleural effusion (Meig’s syndrome).

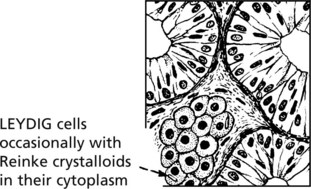

Sertoli-Leydig Cell Tumours (Androblastoma)

Tubules lined by SERTOLI cells, sometimes pyramidal with clear cytoplasm.

This typifies the virilising tumour group. It is a rare tumour. The degree of virilisation varies. Usually a small yellow tumour within the ovary, it is characteristic on microscopy. Some of these tumours are malignant and consist of poorly differentiated spindle cells with occasional tubule formations.

Tumours of the Ovary – Germ Cell

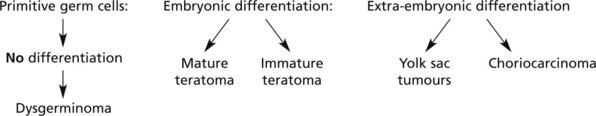

Germ Cell Tumours

These arise from primitive germ cells capable of differentiating in many ways. The following diagram indicates the main varieties of tumour produced.

Dysgerminoma

This is a solid tumour, usually ovoid with a smooth capsule, greyish colour and rubbery consistency. Like all germ cell tumours it is commoner in younger age groups. It is sometimes bilateral. Some cases are found in association with gonadal dysgenesis.

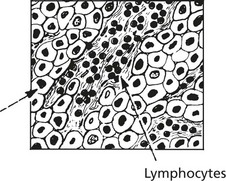

Microscopically, it consists of large clear round cells with large nuclei resembling germ cells. These are arranged in alveoli separated by fine connective tissue infiltrated by lymphocytes. These histological appearances are identical to those of seminoma of the testis.

Dysgerminomas are malignant tumours spreading to para-aortic lymph nodes. They are radio-sensitive and also respond to chemotherapy.

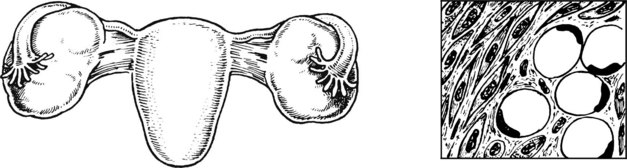

Mature cystic teratoma (dermoid cyst)

This is one of the commonest ovarian tumours and it occurs at all ages.

It is unilocular with an eminence on one aspect from which hairs grow. Teeth may be present. The cyst is lined by stratified squamous epithelium. Sebaceous glands, nervous tissue, respiratory, intestinal epithelium and thyroid tissue may also be present.

Very occasionally the squamous epithelium may undergo malignant change.

Immature Teratoma

The tumours are predominantly solid and are malignant. They contain immature tissues, typically of primitive nerve tissue and mesenchymal tissue. They may metastasise to the peritoneum where the nerve tissue may differentiate (gliomatosis peritonei).

Chemotherapy has greatly improved the prognosis in these cases.

Solid tumours are occasionally seen consisting only of thyroid tissue (struma ovarii) or carcinoid tumour cells.

Tumours of the Ovary – Germ Cell and Secondaries

Secondary Tumours

The ovaries are often the site of metastases from the breast, lung, intestinal system, etc. They are commonest during the child-bearing years.

Krukenberg Tumour

This is a very characteristic secondary tumour due to metastatic deposits from an undiscovered stomach carcinoma in a pre-menopausal woman. Both ovaries are involved. They are firm and fibrous, of equal size, smooth and slightly lobulated. No adhesions are present.

Histologically there are large tumour cells, eccentric nuclei and clear cytoplasm containing mucin (signet ring cells) lying in a spindle-celled stroma

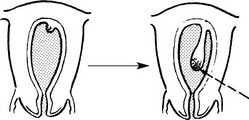

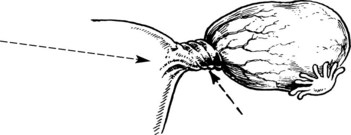

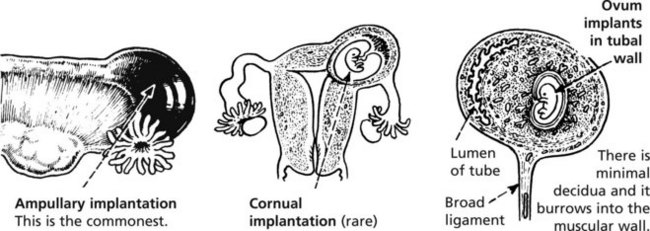

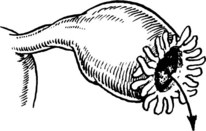

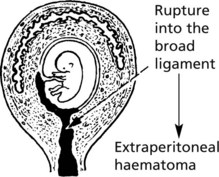

Ectopic Pregnancy

This means implantation of the fertilised ovum outside the uterine cavity usually in the fallopian tube.

Aetiology. Most commonly the tube has been previously damaged by salpingitis, leading to partial blockage of the tube. There has been an increased incidence of ectopic pregnancy in women fitted with intrauterine contraceptive devices.

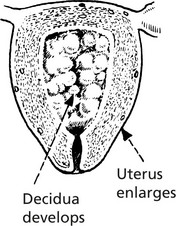

Uterine Changes

Erosion of the tubal tissues by the ovum results in rupture.

This is the commonest finding.

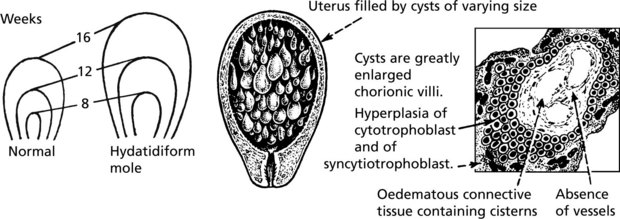

Gestational Trophoblast Disease

This term describes proliferative conditions of placental tissue.

Hydatidiform Mole

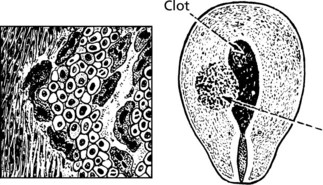

Choriocarcinoma

This is a malignant tumour of trophoblast and is by definition of fetal origin. It usually follows hydatidiform mole. Pleomorphic cytotrophoblast and syncytiotrophoblast, showing numerous mitoses, invade blood vessels causing haemorrhage and early lung metastases either as a single large ‘cannon-ball’ haemorrhagic mass or multiple small emboli (‘snow-storm’ lung). The high blood and urine concentrations of chorionic gonadotrophin are used to monitor progress and treatment which is now usually successful.

The myometrium is infiltrated by masses of malignant trophoblast and blood vessels are eroded.

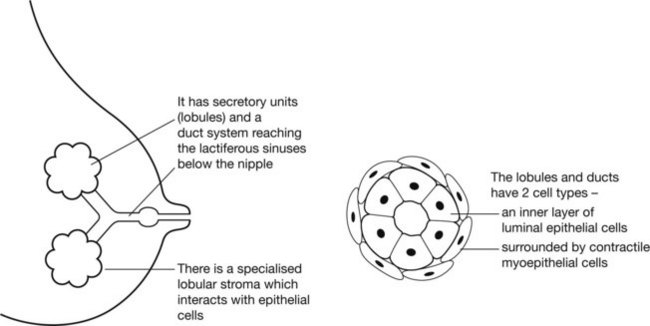

Breast Structure and Function

The breast is a greatly modified sweat gland which has evolved to secrete nourishment to infants.

The breast responds to oestrogen and progesterone both during the menstrual cycle and, especially, during pregnancy in preparation for lactation.

Benign Diseases of the Breast

Acute infection is an occasional complication of lactation.

Fissures or abrasions of the nipple allow staphylococci to be transmitted from the baby. Abscesses may form in the breast with scarring.

Chronic infection e.g. tuberculosis is very uncommon.

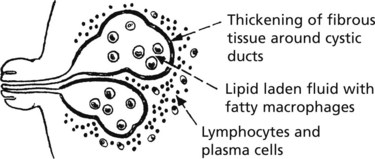

Duct ectasia (plasma cell mastitis)

This chronic inflammatory reaction is associated with ectasia of the ducts (cystic dilatation).

Infection of the dilated ducts allows escape of contents into the tissues resulting in granulomatous reaction. Clinically it may raise suspicion of duct carcinoma.

Traumatic Fat Necrosis occurs especially in large pendulous breasts and results in irregular granulomatous fibrosis which may mimic carcinoma.

In some cases of Silicone Implant, continuing granulomatous inflammation with fibrosis occurs in the ‘capsule’ due to leakage of silicone.

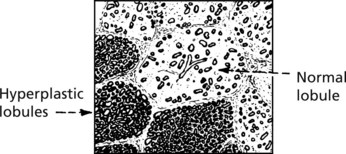

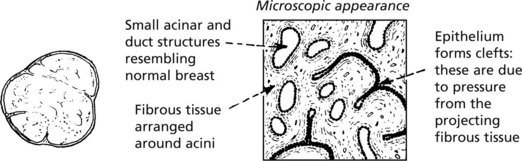

Fibrocystic Change

This change presents as a lump or lumpiness of the breast in pre-menopausal women.

Uniform proliferation of acinar epithelium without acinar expansion.

Fibrocystic change is very common, and the various changes are ascribed to abnormal and exaggerated responses of the breast tissues to the cyclical physiological menstrual hormonal stimuli; they are essentially benign.

Fibroadenoma

This is a benign nodular proliferation, now considered to be a component of fibrocystic change and not a true neoplasm. It is usually single, occurring in young women. It presents clinically as a small, firm, mobile lump.

Gross appearance Well circumscribed, rounded and elastic in consistency: glistening, greyish cut surface (1-3 cm diam.)

Radial Scar

This small (up to 1 cm diam.), firm lesion shows a central dense fibrous core with radiating fingers of fibrosis entrapping and distorting glandular elements. It is benign but can be confused with carcinoma even on histological examination.

Similar but larger lesions, also detected by mammography, are known as complex sclerosing lesions.

Benign Breast Tumours and in situ Carcinoma

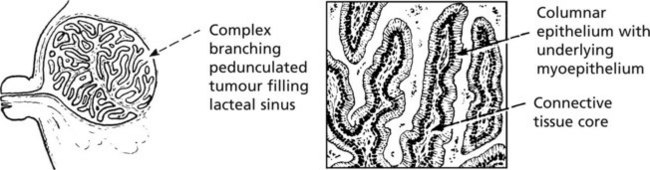

Duct Papilloma

This tumour may develop in any part of the duct system of the breast, but is most common in the lacteal sinuses at the nipple. Two forms exist:

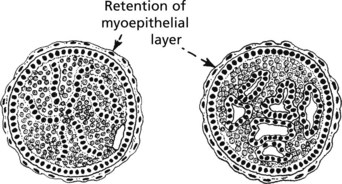

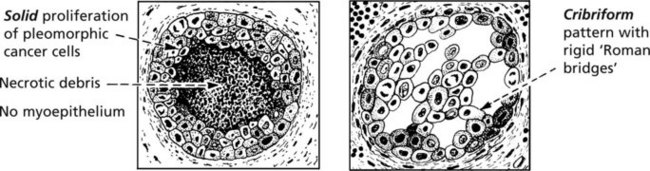

Ductal Carcinoma in-situ (DCIS)

The cells lining the ducts show cytological features of malignancy but have not yet invaded the stroma. Focal calcification allows it to be detected by mammographic screening or it may present as a palpable mass.

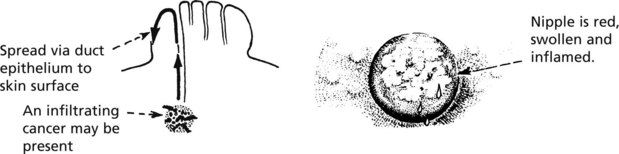

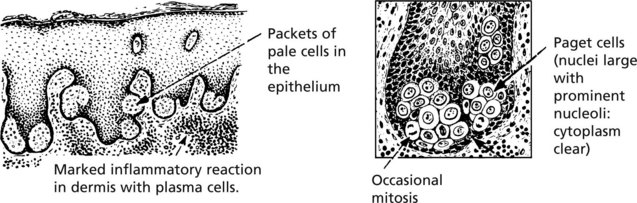

DCIS is graded into high and low grade, the former having a higher risk of invasive malignancy. Intraepithelial spread of DCIS into the nipple skin gives rise to Paget’s disease.

Lobular carcinoma in situ. This lesion is usually multifocal and bilateral. The breast acini of affected lobules are distended by fairly uniform cells which grow into the duct system or break through basement membrane to become infiltrative carcinoma, either of lobular or ductal type.

Carcinoma of the Breast

This is the commonest form of malignancy in women and rarely occurs in men. It may be found in any part of the breast but most frequently it is in the upper outer quadrant.

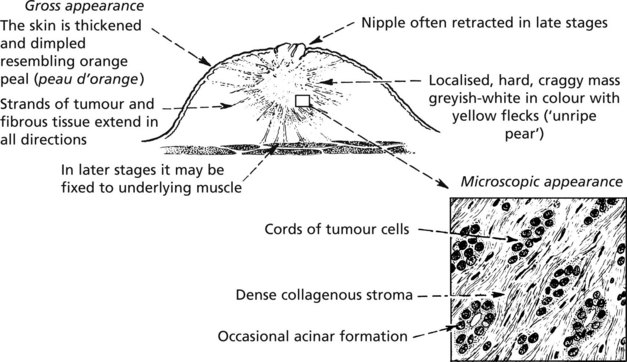

Infiltrating Ductal Carcinoma

This, the commonest form, presents as a firm to hard lump. The following illustrations show a large carcinoma with significant local spread. It is emphasised that modern screening methods aim to detect the disease at a much earlier stage.

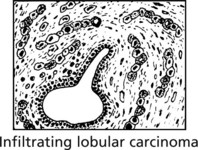

Infiltrating Lobular Carcinoma

Ten per cent of breast cancers are of this type. There is a 10% chance of a similar tumour arising in the contralateral breast. Microscopically the tumour infiltrates the tissues as single files of malignant cells.

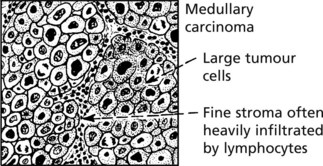

More rare forms of breast cancer are tubular carcinoma – showing well differentiated cells often with intra-tubular calcification: medullary carcinoma – a highly cellular tumour with a florid lymphocytic infiltrate, and mucinous carcinoma where the malignant cells lie in pools of mucin.

Local Spread: In late stages local infiltration causes skin ulceration and there may be direct penetration of the chest wall. Intra-epithelial spread occurs. The classical example is paget’s disease of the nipple – which may complicate intra-duct carcinoma.

Microscopic examination reveals:

Metastatic Spread: This is by lymphatic and blood streams.

Early (When the tumour is still small) |

via LYMPHATICS | via BLOOD STREAM to bone marrow where cells can lie dormant for long periods. |

| Late | Local spread via skin lymphatics causing:

(b) Blockage of dermal lymphatics: oedema of skin except at anchorage points, ‘peau d’orange’ (see p.241).

| Secondaries appear in many viscera, particularly liver, lung and bone (spine, long bones) |

Prognosis

The most important factors determining prognosis are:

These factors are summarised in prognostic indices such as the Nottingham Prognostic Index, based on size, lymph node status and grade.

Aetiology

Breast cancer is uncommon below the age of 30 years. The risk increases with age, the maximal incidence being in the later decades.

The important risk factors are:

There is a strong familial association. Mutation of genes, BRCA1 on chromosome 17 and BRCA2 on chromosome 11, are responsible for many cases of breast cancer in young women with a positive family history. Deletion of tumour suppressor genes has been identified (mutation of suppressor gene p53 is common) – Li-Fraumeni syndrome.

Screening For Breast Cancer

The aim of screening is to detect either pre-malignant conditions or cancer at an early stage and is very important where there is a family history of cancer. Mammography is capable of detecting intra-duct carcinoma and pre-cancerous lesions. Focal calcification is an important indicator but is not diagnostic of malignancy because it also occurs in benign lesions. Whatever method of screening is used the diagnosis must be established on morphological evidence using fine needle aspiration, needle biopsy and, sometimes, open biopsy.

Other rare tumours of the breast include phyllodes tumour – large and usually benign, affecting elderly women: occasionally sarcoma of the stroma is present. Soft tissue sarcomas and primary lymphoma are rare.

The Male Breast

Breast disease is uncommon in men. Abnormal enlargement – gynaecomastia – may occur in a temporary form at puberty or as a permanent feature in Klinefelter’s syndrome (XXY). Oestrogen metabolic upsets (e.g. in liver disease) or excess intake (e.g. treatment of prostatic cancer) are other causes. All tumours are rare but breast cancer does occur.