CHAPTER 13 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

CHAPTER 13 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurobehavioral disorder defined by symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. Clinical guidelines emphasize the use of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders, Fourth Edition, criteria to diagnose ADHD (Table 13-1). These criteria require that the child have symptoms in at least two environments and functional impairment in addition to the symptoms of the disorder for diagnosis.

TABLE 13-1 Diagnostic Criteria for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Code based on type:

314.01 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Combined Type: if both criteria A1 and A2 are met for the past 6 mo

314.00 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Predominantly Inattentive Type: if criterion A1 is met but criterion A2 is not met for the past 6 mo

314.01 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Predominantly Hyperactive, Impulsive Type: if criterion A2 is met but criterion A1 is not met for the past 6 mo

314.9 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Not Otherwise Specified

From the American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed (DSM-IV), Arlington, Va, 1994, American Psychiatric Association.

ETIOLOGY

ADHD is a complex of symptoms with diverse etiology. There is evidence that ADHD runs in some families, but there is no evidence of any single gene that determines ADHD type. Although most cases of ADHD occur in typically developing children, ADHD can be seen in children who have developmental disorders, including fetal alcohol syndrome and Down syndrome, as well as in children who have had varying levels of brain injury, including perinatal brain damage. Most commonly, there is no identified cause of ADHD. It is likely that the symptoms of ADHD represent a final common pathway of diverse causes, including genetic, organic, and environmental etiologies (perhaps in combination).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The estimated prevalence of ADHD in U.S. school-age community populations is 8% to 10%. There is a twofold to threefold higher prevalence in boys than in girls. Girls are more likely to be diagnosed with inattentive-type ADHD. Symptoms of ADHD persist into adolescence in 60% to 80% of patients. Many continue to have symptoms into adulthood.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The diagnosis of ADHD is made by history. The clinician should elicit the history by interview using open-ended questions focused on specific behaviors and by using ADHD-specific rating scales. ADHD rating scales are sensitive and specific for diagnosing ADHD. The Conners Questionnaires and the Vanderbilt forms are two commonly used parent and teacher questionnaires.

A physical examination is essential to rule out underlying medical or developmental problems. The examination should include the observation of the child and the parents and their relationship. It is a mistake to interpret absence of hyperactivity in the office as a sign that the child does not have ADHD. It is common for children with ADHD to focus without hyperactivity in an environment that has low stimulation and little distraction.

Laboratory and imaging studies are not routinely recommended. The clinician may consider thyroid function studies, blood lead levels, genetic karyotyping, and brain imaging studies if any of these studies are indicated by past medical history, environmental history, or physical examination. These studies do not confirm ADHD, but they are useful in excluding other conditions.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis includes the possibility that the child’s behavior is within the range of normal. Other possibilities include hyperactivity and distractibility secondary to hyperthyroidism or lead intoxication. Chaotic living situations also can lead to symptoms of hyperactivity, distractibility, and inattention. Children who have symptoms of ADHD in only one setting may be having problems secondary to cognitive level, level of emotional maturity, or feelings of well-being in that setting.

Speech-language delay and learning disabilities can occur with ADHD (see Chapter 8). Psychiatric conditions, such as conduct disorder, depression, and anxiety disorder, also are more common in children with ADHD than in the general population (see Section 4).

TREATMENT

Management begins with recognizing ADHD as a chronic condition and educating affected children and their parents about the symptoms of ADHD and strategies to control adverse effects on learning, school functioning, social relationships, and family life. Children with ADHD benefit from behavioral approaches to accommodate their condition. It is helpful to provide structure, routine, and appropriate behavioral goals. Some children benefit from social skills counseling or mental health treatment to assist behavior change or to preserve self-esteem.

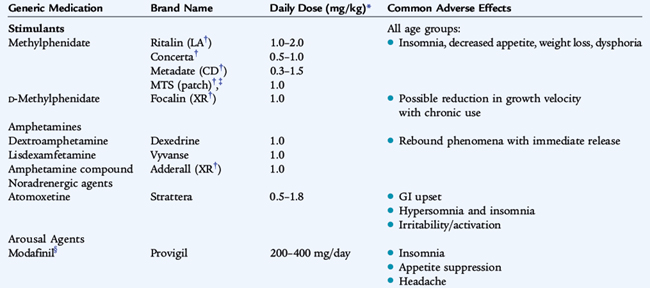

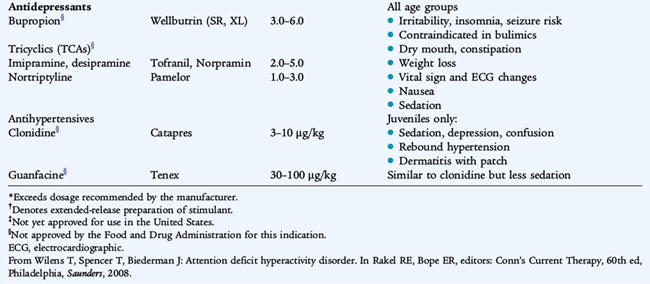

Stimulant medication is effective for managing the symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and distractibility in most children with ADHD. Stimulant medications do not treat the comorbid conditions and do not improve intelligence. Short-acting, intermediate-acting, and long-acting methylphenidate and long-acting dextroamphetamine are widely used stimulant medications. Nonstimulant medications, including atomoxetine, may be helpful for children who have not responded to stimulant medications. Alpha agonists such as clonidine and guanfacine hydrochloride also can be helpful for children with ADHD, especially for children with sleep disorders. Dosing for ADHD medications is listed in Table 13-2. Common side effects of stimulant medication include appetite suppression and sleep disturbance. These side effects usually can be managed by careful adjustment of dosage and timing of the medication.

Many parents worry that their child may develop illicit drug use and even addiction because of taking stimulant medication. Children with ADHD may be at increased risk for drug use during adolescence because of their impulsivity. Nonetheless, there is a decreased risk of drug abuse in children with ADHD who are well managed medically.

COMPLICATIONS

ADHD may be associated with academic underachievement, difficulties in interpersonal relationships, and poor self-esteem.

PREVENTION

Child-rearing practices that include promoting calm environments and opportunities for increasing length of focus on age-appropriate activities may be helpful. Limiting time spent watching television and playing rapid-response video games also may be prudent because these activities reinforce short attention span. Prevention of secondary disabilities can be achieved by education of medical professionals and educators about the signs and symptoms of ADHD and the most appropriate behavioral and pharmaceutical interventions.