CHAPTER 89 Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis

CHAPTER 89 Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis

ETIOLOGY

The chronic arthritides of childhood include several types, the most common of which is juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA). The classification of these arthritides is evolving, and newer nomenclature of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), which includes other types of juvenile arthritis such as enthesitis-related arthritis and psoriatic arthritis, will soon replace the older JRA classification. The etiology of this autoimmune disease is unknown. The common underlying manifestation of this group of illnesses is the presence of chronic synovitis, or inflammation of the joint synovium. The synovium becomes thickened and hypervascular with infiltration by lymphocytes, which also can be found in the synovial fluid along with inflammatory cytokines. The inflammation leads to production and release of tissue proteases and collagenases. If left untreated, this can lead to tissue destruction, particularly of the articular cartilage and eventually the underlying bony structures.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

JRA is the most common chronic rheumatologic disease of childhood, with a prevalence of 1:1000 children. The disease has two peaks, one at 1 to 3 years and one at 8 to 12 years, but it can occur at any age. Girls are affected more commonly than boys, particularly with the pauciarticular form of the illness.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

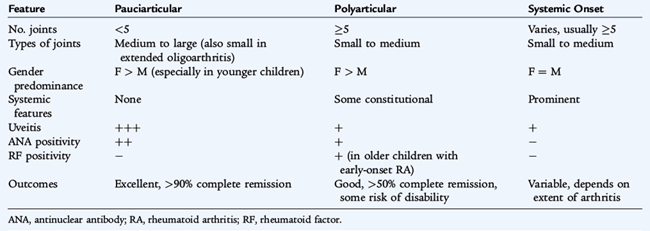

JRA can be divided into three subtypes—pauciarticular, polyarticular, and systemic onset—each with particular disease characteristics (Table 89-1). Although the onset of the arthritis is slow, the actual joint swelling is often noticed by the child or parent acutely, such as after an accident or fall, and can be confused with trauma (although traumatic effusions are rare in children). The child may develop pain and stiffness in the joint that limit use. The child rarely refuses to use the joint at all. Morning stiffness and gelling also can occur in the joint and, if present, can be followed in response to therapy.

On physical examination, signs of inflammation are present, including joint tenderness, erythema, and effusion (Fig. 89-1). Joint range of motion may be limited because of pain, swelling, or contractures from lack of use. In children, because of the presence of an active growth plate, it may be possible to find bony abnormalities of the surrounding bone, causing bony proliferation and localized growth disturbance. In a lower extremity joint, a leg length discrepancy may be appreciable if the arthritis is asymmetric.

FIGURE 89-1 An affected knee in a patient with pauciarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Note sizeable effusion, bony proliferation, and flexion contracture.

All children with chronic arthritis are at risk for chronic iridocyclitis or uveitis. There is an association between human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) (HLA-DR5, HLA-DR6, and HLA-DR8) and uveitis. The presence of a positive antinuclear antibody identifies children with arthritis who are at higher risk for chronic uveitis. Although all children with JRA are at increased risk, the subgroup of children, particularly young girls, with pauciarticular JRA and a positive antinuclear antibody are at highest risk, with an incidence of uveitis of 80%. The uveitis associated with JRA can be asymptomatic until the point of visual loss, making it the primary treatable cause of blindness in children. It is crucial for children with JRA to undergo regular ophthalmologic screening with a slit-lamp examination to identify anterior chamber inflammation and to initiate prompt treatment of any active disease.

Pauciarticular Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis

Pauciarticular JRA (or oligoarticular JIA) is defined as the presence of arthritis in fewer than five joints within 6 months of diagnosis. This is the most common form of JRA, accounting for approximately 50% of cases. Pauciarticular JRA presents in young children, with a peak at 1 to 3 years and another peak at 8 to 12 years. The arthritis is found in medium-sized to large joints; the knee is the most common joint involved, followed by the ankle and the wrist. It is unusual for small joints, such as the fingers or toes, to be involved, although this may occur. Neck and hip involvement also is uncommon. Children with pauciarticular JRA may be otherwise well without any evidence of systemic inflammation (fever, weight loss, or failure to thrive) or have any laboratory evidence of systemic inflammation (elevated white blood cell count or erythrocyte sedimentation rate). A subset of these children later develops polyarticular disease (called extended oligoarthritis in the new JIA classification).

Polyarticular Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis

Polyarticular JRA describes children with arthritis in five or more joints within the first 6 months of diagnosis and accounts for about 40% of cases. Children with polyarticular JRA tend to have symmetric arthritis, which can affect any joint but typically involves the small joints of the hands, feet, ankles, wrists, and knees. The cervical spine can be involved, leading to fusion of the spine over time. In contrast to pauciarticular JRA, children with polyarticular disease can present with evidence of systemic inflammation including malaise, low-grade fever, growth retardation, anemia of chronic disease, and elevated markers of inflammation. Polyarticular JRA can present at any age, although there is a peak in early childhood. There is a second peak in adolescence, but these children differ by the presence of a positive rheumatoid factor and most likely represent a subgroup with true adult rheumatoid arthritis; the clinical course and prognosis are similar to the adult entity.

Systemic-Onset Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis

A small subgroup of patients (approximately 10%) with juvenile arthritis do not present with onset of arthritis but rather with preceding systemic inflammation. This form of JRA manifests with a typical recurring, spiking fever, usually once or twice per day, which can occur for several weeks to months. This is accompanied by a rash, typically morbilliform and salmon-colored. The rash may be evanescent and occur only at times of high fever. Rarely, the rash can be urticarial in nature. Internal organ involvement also occurs. Serositis, such as pleuritis and pericarditis, occurs in 50% of children. Pericardial tamponade rarely may occur. Hepatosplenomegaly occurs in 70% of children. Children with systemic-onset JRA appear sick; they have significant constitutional symptoms, including malaise and failure to thrive. Laboratory findings show the inflammation, with elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, white blood cell count, and platelet counts and anemia. The arthritis of JRA follows the systemic inflammation by 6 weeks to 6 months. The arthritis is typically polyarticular in nature and can be extensive and resistant to treatment, placing these children at highest risk for long-term disability.

LABORATORY AND IMAGING STUDIES

Most children with pauciarticular JRA have no laboratory abnormalities. Children with polyarticular and systemic-onset disease commonly show elevated acute phase reactants and anemia of chronic disease. In all pediatric patients with joint or bone pain, a complete blood count should be performed to exclude leukemia, which also can present with limb pain (see Chapter 155). All patients with pauciarticular JRA should have an antinuclear antibody test to help identify those at higher risk for uveitis. Older children and adolescents with polyarticular disease should have a rheumatoid factor performed to identify children with early onset adult rheumatoid arthritis.

Diagnostic arthrocentesis may be necessary to exclude suppurative arthritis in children who present with acute onset of monarticular symptoms. The synovial fluid white blood cell count is typically less than 50,000 to 100,000/mm3 and should be predominantly lymphocytes, rather than neutrophils seen with suppurative arthritis. Gram stain and culture should be negative (see Chapter 118).

The most common radiologic finding in the early stages of JRA is a normal bone x-ray. Over time, periarticular osteopenia, resulting from decreased mineralization, is most commonly found. Growth centers may be slow to develop, whereas there may be accelerated maturation of growth plates or evidence of bony proliferation. Erosions of bony articular surfaces may be a late finding. If the cervical spine is involved, fusion of C1–4 may occur, and atlantoaxial subluxation may be demonstrable.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

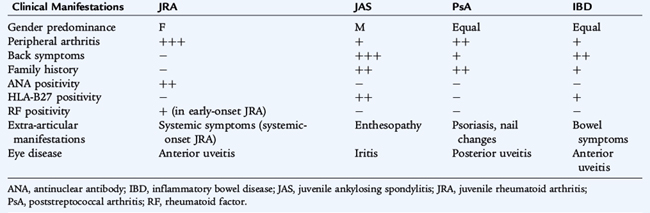

The diagnosis of JRA is established by the presence of arthritis, the duration of the disease for at least 6 weeks, and exclusion of other possible diagnoses. Although a presumptive diagnosis of systemic-onset JRA can be established for a child during the systemic phase, a definitive diagnosis is not possible until arthritis develops. Children must be younger than 16 years of age at time of onset of disease; the diagnosis of JRA does not change when the child becomes an adult. Because there are so many other causes of arthritis, these disorders need to be excluded before providing a definitive diagnosis of JRA (Table 89-2). The acute arthritides can affect the same joints as JRA but have a shorter time course. In particular, JRA can be confused with the spondyloarthropathies, or enthesitis-related arthritidis, which are associated with spinal involvement or inflammation of tendinous insertions. All forms of pediatric arthritides can present with peripheral arthritis before other manifestations and initially may be misclassified (Table 89-3).

TREATMENT

The treatment of JRA focuses on suppressing inflammation, preserving and maximizing function, preventing deformity, and preventing blindness. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the first choice in the treatment of JRA. Naproxen, sulindac, ibuprofen, indomethacin, and others have been used successfully. Aspirin products, the mainstay of arthritis treatment in the past, have been replaced in large part by NSAIDs, not only because of concerns about Reye syndrome but also because of the convenience of twice daily rather than four times daily dosing. Systemic corticosteroid medications, such as prednisone and prednisolone, should be avoided in all but the most extreme circumstances, such as for severe systemic-onset JRA with internal organ involvement or for significant active arthritis leading to inability to ambulate. In this circumstance, the corticosteroids are used as bridging therapy until other medications take effect. For patients with a few isolated inflamed joints, intra-articular corticosteroids may be helpful.

Second-line medications, such as hydroxychloroquine and sulfasalazine, have been used in patients whose arthritis is not completely controlled with NSAIDs alone. Methotrexate, given either orally or subcutaneously, has become the drug of choice for polyarticular and systemic-onset JRA, which may not respond to baseline agents alone. Methotrexate can cause bone marrow suppression and hepatotoxicity; regular monitoring can minimize these risks. Leflunomide, with a similar adverse effect profile to methotrexate, has also been used. Biologic agents that inhibit tumor necrosis factor-α and block the inflammatory cascade, including etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab, are effective in the treatment of JRA. The risks of these agents are greater, however, and include serious infection and, possibly, increased risk of malignancy. Anakinra, an interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, is also beneficial in the treatment of systemic-onset JRA.

COMPLICATIONS

Complications with JRA result primarily from the loss of function of an involved joint secondary to contractures, bony fusion, or loss of joint space. Physical and occupational therapy, professionally and through home programs, are crucial to preserve and maximize function. More serious complications stem from associated uveitis; if left untreated, it can lead to serious visual loss or blindness.

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis of JRA is excellent, with an overall 85% complete remission rate. Children with pauciarticular JRA uniformly tend to do well, whereas children with polyarticular disease and systemic-onset disease constitute most children with functional disability. Systemic-onset disease, a positive rheumatoid factor, poor response to therapy, and the presence of erosions on x-ray all connote a poorer prognosis. The importance of physical and occupational therapy cannot be overstated because when the disease remits, the physical limitations remain with the patient into adulthood.