CHAPTER 117 Osteomyelitis

CHAPTER 117 Osteomyelitis

ETIOLOGY

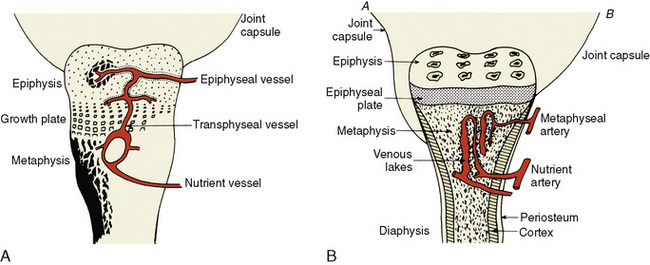

Syndromes of pediatric osteomyelitis include acute hematogenous osteomyelitis, which is accompanied by bacteremia; subacute osteomyelitis, which usually follows local inoculation by penetrating trauma and is not associated with systemic symptoms; and chronic osteomyelitis, which results from an untreated or inadequately treated bone infection. In children beyond the newborn period and without hemoglobinopathies, bone infections occur almost exclusively in the metaphysis. Sluggish blood flow through tortuous vascular loops unique to this site in long bones is a possible explanation for this phenomenon. Preceding nonpenetrating trauma often is reported and may lead to local bone injury that predisposes to infection. Bone infections in children with sickle cell disease occur in the diaphyseal portion of the long bones, probably as a consequence of antecedent focal infarction. In children younger than 1 year of age, capillaries perforate the epiphyseal growth plate, permitting spread of infection across the epiphysis which can lead to suppurative arthritis (Fig. 117-1A). In older children, the infection is contained in the metaphysis because the vessels no longer cross the epiphyseal plate (see Fig. 117-1B).

FIGURE 117-1 A, Major structures of the bone of an infant before maturation of the epiphyseal growth plate. Note the transphyseal vessel, which connects the vascular supply of the epiphysis and metaphysis, facilitating spread of infection between these two areas. B, Major structures of the bone of a child. Joint capsule A inserts below the epiphyseal growth plate, as in the hip, elbow, ankle, and shoulder. Rupture of a metaphyseal abscess in these bones is likely to produce pyarthrosis. Joint capsule B inserts at the epiphyseal growth plate, as in other tubular bones. Rupture of a metaphyseal abscess in these bones is likely to lead to a subperiosteal abscess, but seldom to an associated pyarthrosis.

(From Gutman LT: Acute, subacute, and chronic osteomyelitis and pyogenic arthritis in children. Curr Prob Pediatr 15:1–72, 1985.)

Staphylococcus aureus is responsible for most culture-positive skeletal infections (Table 117-1). Group B streptococcus and S. aureus are major causes in neonates. Sickle cell disease and other hemoglobinopathies predispose to osteomyelitis caused by Salmonella and S. aureus. Pasteurella multocida osteomyelitis may follow cat or dog bites. The use of polymerase chain reaction testing reveals that a significant percentage of culture negative osteomyelitis is due to Kingella kingae. Conjugate vaccine has reduced greatly the incidence of Haemophilus influenzae infections; similar reductions of Streptococcus pneumoniae infections are anticipated with the conjugate pneumococcal vaccine.

TABLE 117-1 Pathogenic Organisms Identified in Culture-Positive Acute Osteomyelitis in Children Beyond the Neonatal Period

| Organism | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 25–60 |

| Haemophilus influenzae type b | 4–12 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 2–5 |

| Group A streptococci | 2–4 |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | <1 |

| Neisseria meningitidis | <1 |

| Salmonella* | <1 |

| None identified | 10–15 |

* Especially in persons with hemoglobinopathies.

Subacute focal bone infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and S. aureus usually occur in ambulatory persons who sustain puncture wounds of the foot. Pseudomonas chondritis is associated strongly with puncture wounds through sneakers, which harbor Pseudomonas in the foam insole. S. aureus is the most common cause of chronic osteomyelitis. Multifocal recurrent osteomyelitis is a poorly understood syndrome characterized by recurrent episodes of fever, bone pain, and radiographic findings of osteomyelitis; no pathogen has been confirmed as the cause of this syndrome.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Osteomyelitis may occur at any age but is most common in children 3 to 12 years of age and affects boys twice as frequently as girls. Hematogenous osteomyelitis is the most common form in infants and children. Osteomyelitis from penetrating trauma or peripheral vascular disease is more common in adults. Osteomyelitis from penetrating injuries of the foot is more common in summer months when children are outdoors and exploring.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The most common presenting complaints are focal pain, exquisite point tenderness over the bone, warmth, erythema, swelling, and decreased use of the affected extremity. Fever, anorexia, irritability, and lethargy may accompany the focal findings. Weight bearing and active and passive motion are refused, which mimics paralysis (pseudoparalysis). Muscle spasm may make the extremity difficult to examine. The adjacent joint space may be involved in young children (see Chapter 118).

Usually only one bone is involved. The femur, tibia, or humerus is affected in two thirds of patients. Infections of the bones of the hands or feet account for an additional 15% of cases. Flat bone infections, including the pelvis, account for approximately 10% of cases. Vertebral osteomyelitis is notable for an insidious onset, vague symptoms, backache, occasional spinal cord compression, and usually little associated fever or systemic toxicity. Patients with osteomyelitis of the pelvis may present with fever, limp, and vague abdominal, hip, groin, or thigh pain.

LABORATORY AND IMAGING STUDIES

The presence of leukocytosis is inconsistent. Blood cultures are important but are negative in many cases. Elevated acute phase reactants, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), are sensitive but nonspecific findings of osteomyelitis. Serial determinations of ESR and CRP are helpful in monitoring the course of the illness and response to treatment. Direct subperiosteal or metaphyseal needle aspiration is the definitive procedure for establishing the diagnosis. Identification of bacteria in aspirated material by Gram stain can establish the diagnosis within hours of clinical presentation. Surgical drainage may be needed after bone aspiration.

Plain radiographs are a useful initial study (Fig. 117-2). The earliest radiographic finding of acute systemic osteomyelitis, at about 9 days, is loss of the periosteal fat line. Periosteal elevation and periosteal destruction are later findings. Brodie abscess is a subacute intraosseous abscess that does not drain into the subperiosteal space and is classically located in the distal tibia. Sequestra, portions of avascular bone that have separated from adjacent bone, frequently are covered with a thickened sheath, or involucrum, both of which are hallmarks of chronic osteomyelitis.

FIGURE 117-2 Multifocal acute osteomyelitis in a 3-week-old infant with multiple joint swelling and generalized malaise. Frontal (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of the left knee show focal destruction of the distal femoral metaphysis with periosteal reaction and generalized soft tissue swelling. Frontal (C) and lateral (D) views of the right knee show an area of focal bone destruction at the distal femoral metaphysis with periosteal reaction and medial soft tissue swelling. Needle aspiration of multiple sites revealed Staphylococcus aureus.

(From Moffett KS, Aronoff SC: Osteomyelitis. In Jenson HB, Baltimore RS [eds]: Pediatric Infectious Diseases: Principles and Practice, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 2002, p 1038.)

Radionuclide scanning for osteomyelitis has largely been supplanted by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which is sensitive to the inflammatory changes in the marrow even during the earliest stages of osteomyelitis. Technetium-99m bone scans are useful for identifying multifocal disease. Gallium-67 scans are often positive if the technetium-99m bone scan is negative.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Osteomyelitis must be differentiated from infectious arthritis (see Chapter 118), cellulitis, fasciitis, diskitis, trauma, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and malignancy.

TREATMENT

Initial antibiotic therapy for osteomyelitis is based on the likely organism for the age of the child, Gram stain of bone aspirate, and associated diseases (Table 117-2). Initial therapy includes an antibiotic that targets S. aureus such as oxacillin, nafcillin, or clindamycin. Vancomycin should be used if methicillin-resistant S. aureus is suspected. For patients with sickle cell disease, initial therapy should include an antibiotic with activity against Salmonella.

TABLE 117-2 Recommended Antibiotic Therapy for Osteomyelitis in Children

| Common Pathogen | Recommended Treatment* |

|---|---|

| ACUTE HEMATOGENOUS OSTEOMYELITIS | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | |

| Methicillin-sensitive | Nafcillin (or oxacillin) or cephazolin |

| Methicillin-resistant | Clindamycin or vancomycin or linezolid |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Penicillin G or ceftriaxone/cefotaxime or vancomycin |

| Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococci) | Penicillin G |

| SUBACUTE FOCAL OSTEOMYELITIS | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Ceftazidime or piperacillin-tazobactam plus an aminoglycoside |

| Kingella kingae | Penicillin G or oxacillin |

* Optimal specific therapy is based on susceptibilities of the organism that is isolated.

There is usually a response to intravenous (IV) antibiotics within 48 hours. Lack of improvement after 48 hours indicates that surgical drainage may be necessary or that an unusual pathogen may be present. Surgical drainage is indicated if sequestrum is present, the disease is chronic or atypical, the hip joint is involved, or spinal cord compression is present. Antibiotics are administered for a minimum of 4 to 6 weeks. After initial inpatient treatment and a good clinical response, including decreases in CRP or ESR, home therapy with IV antibiotics or oral antibiotics may be considered if adherence can be ensured.

COMPLICATIONS AND PROGNOSIS

Complications of acute osteomyelitis are uncommon and usually arise because of inadequate or delayed therapy or due to concominant bacteremia. Young children are more likely to have spread of infection across the epiphysis, leading to suppurative arthritis (see Chapter 118). Vascular insufficiency, which affects delivery of antibiotics, and trauma are associated with higher rates of complications.

Hematogenous osteomyelitis has an excellent prognosis if treated promptly and if surgical drainage is performed when appropriate. The poorest outcome is in neonates and in infants with involvement of the hip or shoulder joints (see Chapter 118). Approximately 4% of acute infections recur despite adequate therapy, and approximately 25% of these fail to respond to extensive surgical débridement and prolonged antimicrobial therapy, ultimately resulting in bone loss, sinus tract formation, and occasionally amputation. Sequelae related to retarded growth are most common with neonatal osteomyelitis.

PREVENTION

There are no effective means to prevent hematogenous S. aureus osteomyelitis. Universal immunization of infants with conjugate Hib (Haemophilus influenzae type b) vaccine has practically eliminated serious bacterial infections from this organism, including bone and joint infections. Because the serotypes of S. pneumoniae causing joint infections are represented in the conjugate pneumococcal vaccine, the incidence of pneumococcal osteomyelitis should decrease with widespread immunization.

Children with puncture wounds to the foot should receive prompt irrigation, cleansing, débridement, removal of any visible foreign body or debris, and tetanus prophylaxis. The value of oral prophylactic antibiotics for preventing osteomyelitis after penetrating injury is uncertain.