CHAPTER 198 Fractures

CHAPTER 198 Fractures

Fractures account for 10% to 15% of all childhood injuries. The anatomic, biomechanical, and physiologic differences in children account for unique fracture patterns and management. Fracture terminology helps describe fractures (Table 198-1).

TABLE 198-1 Useful Fracture Terminology

| Complete | The bone fragments separate completely |

| Incomplete | The bone fragments are still partially joined |

| Linear | Referring to a fracture line that is parallel to the bone’s long axis |

| Transverse | Referring to a fracture line that is at a right angle to the bone’s long axis |

| Oblique | Referring to a fracture line that is diagonal to the bone’s long axis |

| Spiral | Referring to a twisting fracture (can be associated with child abuse) |

| Comminution | A fracture that results in several fragments |

| Compaction | The bone fragments are driven into each other |

| Angulation | The fragments have angular malalignment |

| Rotation | The fragments have rotational malalignment |

| Shortening | The fractured ends of the bones overlap |

| Open | A fracture in which the bone has pierced the skin |

The pediatric skeleton has a higher proportion of cartilage and a thicker, stronger, and more active periosteum capable of producing a larger callus more rapidly than in an adult. The thick periosteum may decrease the rate of displaced fractures and stabilize fractures after reduction. Because of the higher proportion of cartilage, the skeletally immature patient can withstand more force before deformation or fracture than adult bone. As children mature into adolescence, the rate of healing slows and approaches that of adults.

PEDIATRIC FRACTURE PATTERNS

Buckle Fractures

The buckle or torus fracture occurs after compression of the bone; the bony cortex does not truly break. These fractures will typically occur in the metaphysis and are stable fractures that heal in approximately 4 weeks with immobilization. A common example is a fall onto an outstretched arm causing a buckle fracture in the distal radius.

Complete fractures occur when both sides of bony cortex are fractured. This is the most common fracture and may be classified as comminuted, oblique, transverse, or spiral, depending on the direction of the fracture line.

Greenstick fractures occur when a bone is angulated beyond the limits of plastic deformation. The bone fails on the tension side and sustains a bend deformity on the compression side. The force is insufficient to cause a complete fracture (Fig. 198-1).

FIGURE 198-1 The greenstick fracture is an incomplete fracture.

(Modified from White N, Sty R: Radiological evaluation and classification of pediatric fractures. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med 3:94–105, 2002.)

Bowing fractures demonstrate no fracture line evident on radiographs, but the bone is bent beyond its limit of plastic deformation. This is not a true fracture, but will heal with periosteal reaction.

Epiphyseal Fractures

Fractures involving the growth plate constitute about 20% of all fractures in the skeletally immature patient. These fractures are more common in males (2:1 male-female ratio). The peak incidence is 13 to 14 years in boys and 11 to 12 years in girls. The distal radius, distal tibia, and distal fibula are the most common locations.

Ligaments frequently insert onto epiphyses. Thus traumatic forces to an extremity may be transmitted to the physis, which is not as biomechanically strong as the metaphysis, so it may fracture with mechanisms of injury that may cause sprains in the adult. The growth plate is most susceptible to torsional and angular forces.

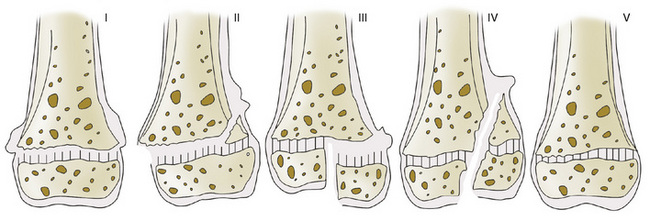

Physeal fractures are described using Salter-Harris classification, which allows for prognostic information regarding premature closure of the growth plate and poor functional outcomes. The higher the type number, the more likely the patient will have complications. There are five main groups (Fig. 198-2):

FIGURE 198-2 The types of growth plate injury as classified by Salter and Harris. See text for descriptions of types I to V.

(From Salter RB, Harris WR: Injuries involving the epiphyseal plate. J Bone Joint Surg Am 45:587, 1963.)

Types I and II fractures can often be managed by closed reduction and do not require perfect alignment. A major exception is the type II fracture of the distal femur which is associated with a poor outcome unless proper anatomic alignment is obtained. Types III and IV fractures require anatomic alignment for successful treatment. Type V fractures can be difficult to diagnose and often result in premature closure of the physis.

MANAGEMENT OF PEDIATRIC FRACTURES

The majority of pediatric fractures can be managed with closed methods. Some fractures need closed reduction to improve alignment. Approximately 4% of pediatric fractures require internal fixation. Patients with open physes are more likely to require internal fixation if they have one of the following fractures:

The goal of internal fixation is to improve and maintain anatomic alignment. This is usually done with Kirschner wires, Steinmann pins, and cortical screws with subsequent external immobilization in a cast until healing is satisfactory. After healing, the hardware is frequently removed to prevent incorporation into the callus and prevent physeal damage.

External fixation without casting is often necessary for pelvic and open fractures. Fractures associated with soft tissue loss, burns, and neurovascular damage benefit from external fixation.

SPECIAL CONCERNS

Remodeling

Fracture remodeling occurs because of a combination of periosteal resorption and new bone formation. Many pediatric fractures do not need perfect anatomic alignment for proper healing. Younger patients have greater potential for fracture remodeling. Fractures that occur in the metaphysis, near the growth plate, may undergo more remodeling. Fractures angulated in the plane of motion also remodel very well. Intra-articular fractures, angulated or displaced diaphyseal fractures, rotated fractures, and fracture deformity not in the plane of motion, tend not to remodel as well.

Overgrowth

Overgrowth occurs in long bones as the result of increased blood flow associated with fracture healing. Femoral fractures in children younger than 10 years of age will frequently overgrow 1 to 3 cm. This is the reason end-to-end alignment for femur and long bone fractures may not be indicated. After 10 years of age, overgrowth is less of a problem, so end-to-end alignment is recommended.

Progressive Deformity

Fractures and injuries to the physis can result in premature closure. If it is a partial closure, the consequence may be an angular deformity. If it is a complete closure, limb shortening may occur. The most commonly affected locations are the distal femur and tibia, and the proximal tibia.

Neurovascular Injury

Fractures and dislocations may damage adjacent blood vessels and nerves. The most common location is the distal humerus (supracondylar fracture) and the knee (dislocation and physeal fracture). It is necessary to perform and document a careful neurovascular examination distal to the fracture (pulse, sensory, and motor function).

Compartment Syndrome

Compartment syndrome is an orthopedic emergency that results from hemorrhage and soft tissue swelling within the tight fascial compartments of an extremity. This can result in muscle ischemia and neurovascular compromise unless it is surgically decompressed. The most common sites are the lower leg (tibial fracture) and arm (supracondylar fracture).

Affected patients have severe pain and decreased sensation in the dermatomes supplied by the nerves located in the compartment. Swollen and tight compartments and pain with passive stretching are present. This can happen underneath a cast and may actually occur when a cast is applied too tightly. It is important to educate all patients with fractures on the signs of ischemia and ensure they realize it is an emergency.

Toddler’s Fracture

This is an oblique fracture of the distal tibia without a fibula fracture. There is often no significant trauma. Patients are usually 1 to 3 years old, but can be as old as 6 and present with limping and pain with weight bearing. There may be minimal swelling and pain. Initial radiographs do not always show the fracture; if symptoms persist, a repeat x-ray in 7 to 10 days may be helpful.

Child Abuse

Child abuse must always be considered in the differential diagnosis of a child with fractures, especially in those younger than 3 years (see Chapter 22). Common fracture patterns that should increase the index of suspicion include multiple fractures in different stages of radiographic healing, spiral fractures of the long bones (forcible twisting of extremity), metaphyseal corner fractures (shaking), fractures too severe for the history, or fractures in nonambulatory infants.

When there is concern for child abuse, the child should have a full evaluation, which may include admission to the hospital. A thorough and well-documented physical examination should focus on soft tissue injuries, the cranium, and a funduscopic examination for retinal hemorrhages or detachment. A skeletal survey or a bone scan may be helpful in identifying other fractures.