CHAPTER 22 Child Abuse and Neglect

CHAPTER 22 Child Abuse and Neglect

Few social problems have as profound an impact on the well-being of children as child abuse and neglect. Each year in the United States, 3 million reports of suspected maltreatment are made to child welfare agencies. Approximately 1 million of these reports are substantiated after investigation by Child Protective Services (CPS). These reports represent only a small portion of the children who suffer from maltreatment. Parental surveys indicate that several million adults admit to physical violence against their children each year, and many more adults report abusive experiences as children. Federal and state laws define child abuse and neglect. Each state determines the process of investigating abuse, protecting children, and punishing perpetrators for their crimes. Much of the abuse that is recognized by mandated reporters does not get reported to CPS for investigation. Adverse childhood events, such as child abuse and neglect, increase the risk of the individual’s developing behaviors in adolescence and adulthood that predict adult morbidity and early mortality. The ability to recognize child maltreatment and effectively advocate for the protection and safety of a child is a great challenge in pediatric practice that can have a profound influence on the health and future well-being of a child.

Child abuse is parental behavior destructive to the normal physical or emotional development of a child. Because personal definitions of abuse vary according to religious and cultural beliefs, individual experiences, and family upbringing, various physicians have different thresholds for reporting suspected abuse to CPS. In every state, physicians are mandated by law to identify and report all cases of suspected child abuse and neglect. It is the responsibility of CPS to investigate reports of suspected abuse to determine whether abuse has occurred and to ensure the ongoing safety of the child. State laws also define intentional or reckless acts that cause harm to a child as crimes. Law enforcement investigates crimes such as sexual abuse and serious physical abuse or neglect for possible prosecution of the perpetrator.

Child abuse and neglect are often considered in broad categories that include physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect. Neglect is the most common, accounting for approximately half of the reports made to child welfare agencies. Child neglect is defined by omissions that prevent a child’s basic needs from being met. These needs include adequate food, clothing, supervision, housing, health care, education, and nurturance. Child abuse and neglect result from a complex interaction of individual, family, and societal risk factors. Although some risk factors, such as parental substance abuse, maternal depression, and domestic violence are strong risk factors for maltreatment, these and other risk factors are better considered as broadly defined markers to alert a physician to a potential risk, rather than determinants of specific abuse and neglect. These risk factors, although important for developing public policies and prevention strategies for maltreatment, should not be used to determine whether a specific patient is a victim of child maltreatment.

The ability to identify victims of child abuse varies by the age of the patient and the type of maltreatment sustained. Children who are victims of sexual abuse are often brought for medical care after the child makes a disclosure, and the diagnosis is obvious. Physically abused infants may be brought for medical evaluation of irritability or lethargy, without a disclosure of trauma. If the infant’s injuries are not severe or visible, the diagnosis may be missed. Approximately one third of infants with abusive head trauma initially are misdiagnosed by unsuspecting physicians, only to be identified after sustaining further injury. Although physicians are inherently trusting of parents, a constant awareness of the possibility of abuse is needed.

PHYSICAL ABUSE

The physical abuse of children by parents affects children of all ages. It is estimated that 1% to 2% of children are physically abused during childhood and that approximately 2000 children are fatally injured each year. Although mothers are most frequently reported as the perpetrators of physical abuse, serious injuries, such as head or abdominal trauma, are more likely to be inflicted by fathers or maternal boyfriends. The diagnosis of physical abuse can be made easily if the child is battered, has obvious external injuries, or is capable of providing a history of the abuse. In many cases, the diagnosis is not obvious. The history provided by the parent is often inaccurate because the parent is unwilling to provide the correct history or is a nonoffending parent who is unaware of the abuse. The child may be too young or ill to provide a history of the assault. An older child may be too scared to do so or may have a strong sense of loyalty to the perpetrator.

A diagnosis of physical abuse initially is suggested by a history that seems incongruent with the clinical presentation of the child (Table 22-1). Although injury to any organ system can occur from physical abuse, some injuries are more common. Bruises are universal findings in nonabused ambulatory children but also are among the most common injury identified in abused children. Bruises suggestive of abuse include those that are patterned, such as a slap mark on the face or looped extension cord marks on the body (Fig. 22-1). Bruises in healthy children generally are distributed over bony prominences; bruises that occur in an unusual distribution, such as isolated to the trunk or neck, should raise concern. Bruises in nonambulatory infants are unusual, occurring in less than 2% of healthy infants seen for routine medical care. Occasionally, a subtle bruise may be the only external clue to abuse and can be associated with significant internal injury.

FIGURE 22-1 Multiple looped cord marks on a 2-year-old abused child who presented to the hospital with multiple untreated burns to the back, arms, and feet.

Burns are common pediatric injuries and usually represent preventable unintentional trauma (see Chapter 44). Approximately 10% of children hospitalized with burns are victims of abuse. Inflicted burns can be the result of contact with hot objects (irons, radiators, or cigarettes) but more commonly result from scalding injuries (Fig. 22-2).Hot tap water burns in infants and toddlers are sometimes the result of intentional immersion injuries, which often occur around toilet training issues. These burns have clear lines of demarcation, uniformity of burn depth, and characteristic pattern.

FIGURE 22-2 A 1-year-old child brought to the hospital with a history that she sat on a hot radiator. Suspicious injuries such as this require a full medical and social investigation, including a skeletal survey to look for occult skeletal injuries and a child welfare evaluation.

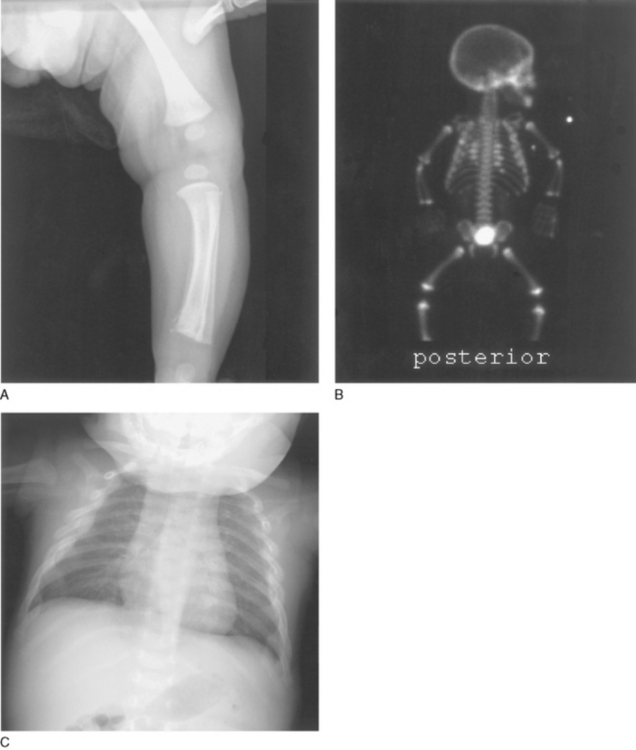

Inflicted fractures occur more commonly in infants and young children. Although diaphyseal fractures are most common in abuse, they are nonspecific for inflicted injury. Fractures that should raise suspicion for abuse include fractures that are unexplained; occur in young, nonambulatory children; or involve multiple bones. Certain fractures have a high specificity for abuse, such as rib, metaphyseal, scapular, vertebral, or other unusual fractures (Fig. 22-3).

FIGURE 22-3 A, Metaphyseal fracture of the distal tibia in a 3-month-old infant admitted to the hospital with severe head injury. There also is periosteal new bone formation of that tibia, perhaps from a previous injury. B, Bone scan of same infant. Initial chest x-ray showed a single fracture of the right posterior fourth rib. A radionuclide bone scan performed 2 days later revealed multiple previously unrecognized fractures of the posterior and lateral ribs. C, Follow-up radiographs 2 weeks later showed multiple healing rib fractures. This pattern of fracture is highly specific for child abuse. The mechanism of these injuries is usually violent squeezing of the chest.

Abdominal injury is an uncommon but serious form of physical abuse. Blunt trauma to the abdomen is the primary mechanism of injury, and infants and toddlers are the most common victims. Injuries to solid organs, such as the liver or pancreas, predominate. Hollow viscus injury occurs more commonly with inflicted trauma than accidental, and injury to solid and hollow organs occurs almost exclusively with abuse. Even in severe cases of trauma, there may be no bruising to the abdominal wall. The lack of external trauma, along with the usual inaccurate history, can cause delay in diagnosis. A careful evaluation often reveals additional injuries. Abdominal trauma is the second leading cause of mortality from physical abuse, although the prognosis is generally good for children who survive the acute assault.

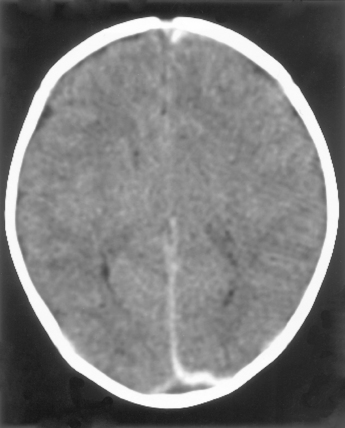

Abusive head trauma is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity from physical abuse. Most victims are young; infants predominate. Shaking and blunt impact trauma cause injuries. The perpetrators are most commonly fathers and boyfriends, and the trauma typically is precipitated by the perpetrator’s intolerance to a crying, fussy infant. Victims present with neurologic symptoms ranging from lethargy and irritability to seizures, apnea, and coma. Unsuspecting physicians misdiagnose approximately one third of infants, and of these, more than 25% are reinjured before diagnosis. Infants most likely to be misdiagnosed include infants with mild injuries, infants who are younger than 6 months of age, and white infants who live in two-parent households. A common finding on presentation is subdural hemorrhage, often associated with progressive cerebral edema (Fig. 22-4). Secondary hypoxic injury is a significant contributor to the pathophysiology of the brain injury. Associated findings include retinal hemorrhages (seen in many, but not all, victims) and skeletal trauma, including rib and metaphyseal fractures. At the time of diagnosis, many head-injured infants have evidence of previous injury. Survivors are at high risk for permanent neurologic sequelae.

FIGURE 22-4 Acute subdural hemorrhage in the posterior interhemispheric fissure in an abused infant.

The extensive differential diagnosis of physical abuse depends on the type of injury (Table 22-2). For children who present with pathognomonic injuries to multiple organ systems, an exhaustive search for medical diagnoses is unwarranted. Children with unusual medical diseases have been incorrectly diagnosed as victims of abuse, emphasizing the need for careful, objective assessments of all children. All infants and young toddlers who present with suspicious injuries should undergo a skeletal survey looking for occult or healing fractures. One third of young infants with multiple fractures, facial injuries, or rib fractures may have occult head trauma. Brain imaging may be indicated for these infants.

TABLE 22-2 Differential Diagnosis of Physical Abuse*

BRUISES

BURNS

FRACTURES

HEAD TRAUMA

* The differential diagnosis of physical abuse varies by the type of injury and organ system involved.

Data from Christian CW: Child abuse physical. In Schwartz MW, editor: The 5-minute pediatric consult, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, 2003, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

SEXUAL ABUSE

Child sexual abuse is the involvement of children in sexual activities that they cannot understand, for which they are developmentally unprepared and cannot give consent to, and that violates societal taboos. Sexual abuse can be a single event, but more commonly it is chronic. Most perpetrators are adults or adolescents who are known to the child and who have real or perceived power over the child. Most sexual abuse involves manipulation and coercion and is typically a physically nonviolent assault. Although assaults by strangers occur, they are infrequent. Perpetrators are more often male than female and include parents, relatives, teachers, family friends, members of the clergy, and other individuals who have access to children. All perpetrators strive to keep the child from disclosing the abuse and often do so with coercion or threats.

Each year, more than 150,000 cases of sexual abuse are substantiated by CPS, which is likely to be a significant underestimation of the incidence. Approximately 80% of victims are girls, although the sexual abuse of boys is under-recognized and under-reported. Children generally come to attention after they have made a disclosure of their abuse. They may disclose to a nonoffending parent, sibling, relative, friend, or teacher. Children seldom disclose their abuse after a single event, and it is common for children to delay disclosure for many weeks, months, or years, especially if the perpetrator has ongoing access to the child. Sexual abuse also should be considered in children who have behavioral problems, although no behavior is pathognomonic. Hypersexual behaviors should raise the possibility of abuse, although some children with these behaviors are exposed to inappropriate sexual behaviors on television or videos or by witnessing adult sexual activity. Sexual abuse occasionally is recognized by the discovery of an unexplained vaginal, penile, or anal injury or by the discovery of a sexually transmitted infection.

In most cases, the diagnosis of sexual abuse is made by the history obtained from the child. In cases in which the sexual abuse has been reported to CPS or the police (or both), and the child has been interviewed before the medical visit, a complete, forensic interview at the physician’s office is not needed. Many communities have systems in place to ensure quality investigative interviews of sexually abused children, and repetitive interviewing of the child should be avoided. If no other professional has spoken to the child about the abuse, or the child makes a spontaneous disclosure to the physician, the child should be interviewed with questions that are open-ended and nonleading. In all cases, the child should be questioned about medical issues related to the abuse, such as timing of the assault and symptoms (bleeding, discharge, or genital pain).

The physical examination should be complete, with careful inspection of the genitals and anus. Most sexually abused children have a normal genital examination at the time of the medical evaluation. Genital injuries are seen more commonly in children who present for medical care within 72 hours of their most recent assault and in children who report genital bleeding, but they are diagnosed in only 5% to 10% of sexually abused children. Many types of sexual abuse (fondling, vulvar coitus, oral-genital contact) do not injure genital tissue, and genital mucosa heals so rapidly and completely that injuries often heal by the time of the medical examination. For children who present within 72 hours of the most recent assault, special attention should be given to identifying acute injury and the presence of blood or semen on the child. Injuries to the oral mucosa, breasts, or thighs should not be overlooked. Forensic evidence collection is needed in a few cases and has the greatest yield when collected in the first 24 hours after an acute assault. Highest yields come from the child’s clothing or bed linens, and efforts should be made to secure these items. Few findings are diagnostic of sexual assault, but findings with the most specificity include acute, unexplained lacerations or ecchymoses of the hymen, posterior fourchette or anus, complete transection of the hymen, unexplained anogenital scarring, or pregnancy in an adolescent with no other history of sexual activity.

The laboratory evaluation of a sexually abused child is dictated by the child’s age, history, and symptoms. Universal screening for sexually transmitted infections for prepubertal children is unnecessary because the risk of infection is low in asymptomatic young children. The type of assault, identity and known medical history of the perpetrator, and the epidemiology of sexually transmitted infections in the community also are considered. Because of the medicolegal implications of the diagnosis, proper methods must be used for testing. In prepubertal children, culture diagnosis remains the gold standard; nonculture diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis do not meet medical or legal standards at this time, although these standards may change in the future, with further experience with nucleic acid amplification testing in young children (Table 22-3). The diagnosis of most sexually transmitted infections in young children requires an investigation for sexual abuse (Table 22-4) (see Chapter 116).

TABLE 22-3 Proper Testing Methods for Sexually Transmitted Infections in Children and Adolescents

| Organism | Infants and Prepubertal Children | Adolescents |

|---|---|---|

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Culture* | Culture, NAAT† |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | Culture‡ | Culture, NAAT† |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | Vaginal wet mount and culture | Vaginal wet mount and culture |

| Syphilis, HIV, hepatitis B and C | Serum tests | Serum tests |

| Herpes simplex virus | Culture | Culture |

FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test.

* Culture from pharynx, anus, vagina, or urethra (boys) is positive for gram-negative, oxidase-positive diplococcus, with two of three confirmatory tests positive (e.g., carbohydrate utilization, direct fluorescent antibody testing, enzyme substrate testing).

† NAAT can be substituted, with positive test confirmed by second NAAT test. Non-NAAT, direct fluorescent antibody, and enzyme immunoassay are not recommended. NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test.

‡ Data are insufficient to adequately assess the utility of nucleic acid amplification tests, but these tests might be an alternative if confirmation is available and culture systems for C. trachomatis are unavailable. Confirmation tests should consist of a second FDA-cleared nucleic acid amplification test that targets a different sequence from the initial test.

TABLE 22-4 Implications of Commonly Encountered or Sexually Associated Infections for Diagnosis and Reporting of Sexual Abuse among Infants and Prepubertal Children

| Sexually Transmitted or Sexually Associated Infections Confirmed | Evidence of Sexual Abuse | Suggested Action |

|---|---|---|

| Gonorrhea | Diagnostic | Report |

| Syphilis | Diagnostic | Report |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | Diagnostic | Report |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | Diagnostic | Report |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | Highly suspicious | Report |

| Condylomata acuminata (anogenital warts) | Suspicious | Report |

| Genital herpes | Suspicious | Report |

| Bacterial vaginosis | Inconclusive | Medical follow-up |

Adapted from the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Guidelines for the evaluation of sexual abuse of children. Pediatrics 103:186–191, 1999. [Published correction Pediatrics 103:149, 1999.] www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/8-2002TG.htm.

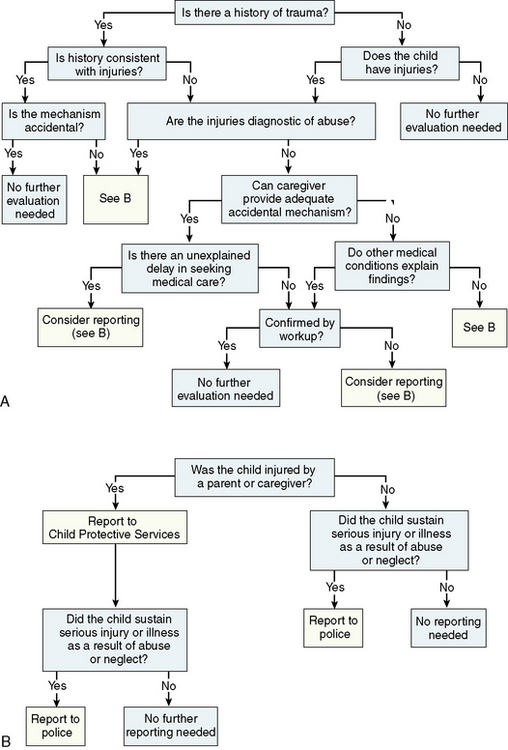

MANAGEMENT

The management of child abuse includes medical treatment for injuries and infections, careful medical documentation of verbal statements and findings, and ongoing advocacy for the safety and health of the child (Fig. 22-5). Parents always should be informed of the suspicion of abuse and the need to report to CPS, focusing on the need to ensure the safety and well-being of the child. Crimes that are committed against children also are investigated by law enforcement, so the police become involved in some, but not all, cases of suspected abuse. Physicians occasionally are called to testify in court hearings regarding civil issues, such as dependency and custody, or criminal issues. Careful review of the medical records and preparation for court are needed to provide an educated, unbiased account of the child’s medical condition and diagnoses.

FIGURE 22-5 A, Approach to initiating the civil and criminal investigation of suspected abuse. B, Reporting to Child Protective Services (CPS) or law enforcement or both in child abuse cases. CPS reports are required when a child is injured by a parent, by an adult acting as a parent, or by a caregiver of the child. The police investigate crimes against children committed by any person, including parents or other caregivers.

(From Christian CW: Child abuse. In Schwartz MW, editor: Clinical handbook of pediatrics, ed 3. Baltimore, 2003, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, pp 192–193.)

The need to prevent child abuse is obvious, yet it is premature to consider the primary prevention of maltreatment an attainable goal. Much of what we consider prevention is in reality reactive: High-risk families are identified and monitored, counseling and therapy are provided when available, and the criminal justice system assists in protecting children and attempting to modify behavior. There are a few partially successful primary prevention programs. Visiting home nursing programs that begin during pregnancy and continue through early childhood may reduce the risk of abuse and neglect. A number of states have mandated educational programs in newborn nurseries for reducing abusive head trauma, and evaluation of the effectiveness of these programs is under way. Physicians always need to remain cognizant of the diagnosis, aware of their professional mandates, and willing to advocate on behalf of these vulnerable patients.