Chapter 2 Staging System for Rehabilitation

Introduction

Sustained postures and repeated movements are often found to be the cause of a musculoskeletal pain problem, and such impairments are well addressed by a thorough examination of the movement system and subsequent treatment. The physical therapist also needs to consider the actual pathoanatomical tissue that is injured or painful; this is otherwise known as the source of symptoms.

In some cases, such as postoperative conditions or acute injury, the source of symptoms becomes particularly relevant because thorough assessment of movement or posture is not possible as the result of specific restrictions or precautions, severe pain, or other constitutional symptoms. For example, a patient that presents to physical therapy after rotator cuff repair will likely have precautions on active range of motion (AROM). Given these restrictions, a full movement examination could not be performed. However, a limited problem-centered examination could be used to obtain information on the integrity or health of the tissues involved, as well as functional limitations.

Regardless of whether a thorough movement examination can be performed, the therapist needs to recognize what tissues are potentially affected by the injury, surgery, or musculoskeletal pain problem. Because biological tissue responds to physical stress in known and predictable ways, identifying the source of symptoms and the phase of healing enables the physical therapist to establish a prognosis for treatment and to develop an effective intervention plan.

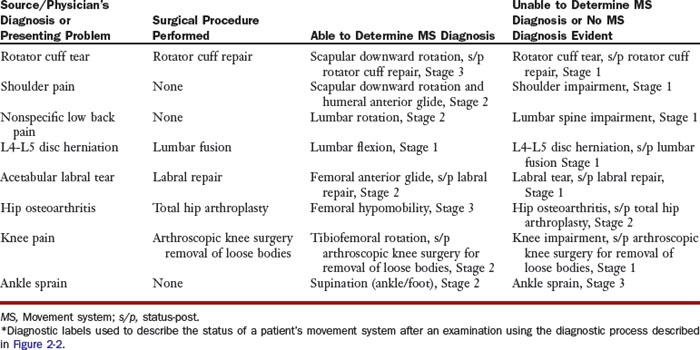

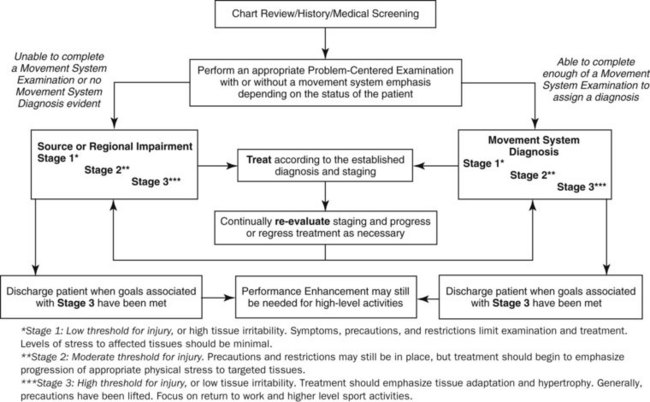

The staging system for rehabilitation was developed to describe the involvement of biological tissue associated with a musculoskeletal pain problem in the presence or absence of specific movement impairments (Figure 2-1). This staging system serves to clarify the level of injury or phase of healing of each tissue involved and can be used with both the established movement system diagnoses or with the physician’s diagnosis of the physiological or anatomical system that is pathological and for which he or she has responsibility.

Figure 2-1 General diagrammatic representation of the diagnostic process. According to the physical stress theory, the stages used within the flow chart can generally be defined by stress restriction/progression. Staging should continually be evaluated.

This chapter explains in detail a staging system of tissue impairment used to describe the source of symptoms. First, the physical stress theory (PST) is described, as well as how this general framework can be used to understand the mechanism of injury to a specific tissue. Second, we briefly review how specific biological tissues respond to the application or removal of physical stress and how each could affect the healing process. Third, detailed information is provided on each stage of rehabilitation and an algorithm explains the movement system evaluation process, with special attention given to the source of symptoms. Finally, case studies illustrate the evaluation process and the use of staging of biological tissue to help guide evaluation and treatment.

Mechanism of Injury: The Physical Stress Theory

Physical stress is defined biomechanically as the force applied to a given area of biological tissue. This definition is true for all mechanical systems, including the human body. Based on substantive research across multiple disciplines, biological tissue, such as muscle,1-8 bone,9-13 or ligament,14-16 clearly responds to such physical stress in predictable ways. Biological tissues may respond favorably (i.e., hypertrophy of muscle) or may respond negatively (i.e., atrophy of muscle, potentially leading to impairment or injury). A thorough discussion of specific tissue impairments related to physical stress is beyond the scope of this book; however, consideration of a theoretical construct that can guide the practicing therapist in staging specific tissue impairments and providing subsequent, appropriate intervention is useful. The PST, which was defined by Mueller and Maluf,17 provides such a framework.

A basic tenet of the PST is that biological tissue can adapt or become more tolerant of stress when specific stresses are applied at or above a certain level. However, for each type of biological tissue, there is also a threshold of adaptation, above which tissue injury or death may occur. Understanding this continuum is important for describing the mechanism of injury and for developing treatment strategies for rehabilitation.

The mechanism of injury to a specific biological tissue depends on (1) the intensity of physical stress applied to the tissue, (2) the duration that the stress is applied, and (3) the specific characteristics of the tissue.17 The easiest example to understand is the injury that occurs as a result of a trauma. In this case, a high amount of physical stress is applied in a relatively short period of time (i.e., motor vehicle accident or fall). The tissue damage in this example is often readily apparent, and significant protection of the tissue might be required for proper healing and recovery of function. Tissue injury can also occur when a moderate amount of stress is applied over a moderate duration, as is the case with repetitive motion injuries. Often these injuries are associated with less than optimal movement patterns as well. Finally, a low amount of physical stress applied to a specific biological tissue over a prolonged period of time can also lead to tissue injury. Thus sustained postural malalignment could result in tissue degeneration and subsequent injury.

Injury to biological tissue, whether sudden (i.e., trauma), progressive (i.e., degeneration), or controlled (i.e., surgery), results in a more narrow window for adaptation relative to healthy tissue. In other words, lower amounts of physical stress are required for tissue injury and re-injury can occur much more quickly. Therefore, to allow for healing, injured biological tissue must often be protected from physical stress. As healing occurs with time, the biological tissue becomes more receptive to different types of physical stress. Eventually, additional physical stress is required by the injured tissue to fully adapt and to improve stress tolerance. By increasing the overall strength of an injured tissue, the likelihood of re-injury is decreased.

Thus a physical therapist should be able to generally evaluate the state of biological tissue after injury and determine whether that tissue should be protected or whether physical stress should be applied to promote tissue adaptation and recovery. The physical therapist should also consider physiological, movement and alignment, extrinsic (i.e., assistive devices, orthotics, etc.), and psychosocial factors when making this decision. Ultimately, the basic concepts of stress restriction and stress progression in response to tissue injury provide the foundation for the stages for rehabilitation presented in this chapter and are used to develop appropriate examination and treatment strategies.

Stages for Rehabilitation

An understanding of the basic mechanisms of tissue injury, subsequent healing and recovery processes, and the predictable manner in which biological tissue responds to stress has sparked the development of a staging system that should be used with any movement system syndrome.18 To be clear, staging in the biomedical field is not unique. Staging systems are used for a wide variety of pathological conditions and describe wound healing,19 musculotendinous injuries,20-22 rotator cuff tears,23 fracture severity,24 and low back pain.25 Most of the staging systems documented in the literature are specific to a type of biological tissue or a specific region of the body and help to describe the severity of the tissue injury. However, no formal staging system exists that can be used to specifically guide the physical therapist through the rehabilitation process, regardless of the body region affected. The stages for rehabilitation were developed to describe the general rehabilitation continuum of tissue healing from the initial injury to full recovery.

Specifically, three stages (Stage 1, Stage 2, or Stage 3) have been identified, and they illustrate the amount of protection required for an injured biological tissue or the amount of physical stress that can be applied to a tissue that is healing. Essentially, these stages describe the threshold for injury for the biological tissue involved. Tissues in the first stage have a low threshold for injury, whereas tissue in the third stage has a high threshold for injury.

The threshold for injury is specific to the biological tissue involved, but the stages are generally more comprehensive in that they are not limited by loosely defined time constraints as is the terminology of acute, subacute, and chronic. Rather, the stages used in this system incorporate moderating factors such as physiological co-morbidities, functional activity performance, precautions and restrictions to movement, psychosocial status, and pain. Thus this staging system provides a framework for the rehabilitation of an individual with a tissue injury, rather than just the tissue itself. As such, the stages for rehabilitation should be used to characterize the source of symptoms for all movement system syndromes, as well as for physician’s diagnoses with undiagnosed or unidentifiable tissue impairments such as an ankle sprain.

Because there is no specific timeframe that defines each of the stages used in this system, there is no clear demarcation between each of the stages. However, Table 2-1 illustrates four key variables that are useful to consider when determining the proper stage: time since injury, symptoms, outcome scores, and functional mobility. Each of these variables provides a general framework for determining the stage for rehabilitation; however, all potential data obtained in the history and examination need to be considered when making a final decision regarding staging. In the next section, each stage is described in detail, including how you determine progression or regression from one stage to another.

Stages: Definition and Assessment

Stage 1 describes a state of low threshold for injury, or high tissue irritability and/or vulnerability. Generally, symptoms, precautions, and restrictions limit the thoroughness of the examination and the intensity of the subsequent treatment. Individuals at Stage 1 often are postsurgical or have had an acute injury or trauma. Thus performing a complete examination might be limited because of pain or physician’s orders. Levels of stress to the affected tissues should be minimal, and the emphasis of treatment is on the protection of the injured tissue. Stage 2 describes a state of moderate threshold for injury. Normally, a complete movement system examination can be performed. Often, patients in this stage do not have precautions or restrictions, but their functional mobility is limited because of pain or other symptoms. For patients presenting to physical therapy postoperatively or after an acute injury, precautions and restrictions may still be in effect. In either case, treatment should begin to emphasize appropriate physical stress to targeted tissues. Stage 3 describes a state of high threshold for injury, or low tissue irritability and/or vulnerability. Generally, all precautions and restrictions have been lifted at this stage and an objective examination may include assessment of high level sport or work activities. For this stage, treatment should emphasize the gradual addition of physical stress to promote tissue adaptation or hypertrophy to restore an optimal level of function.

Table 2-2 provides a summary of key tests and assessments that are used to stage patients appropriately. For each stage, the potential findings for specific examination components are described. As noted previously, there is often no clear demarcation between each of the stages with regards to examination findings. Therefore the purpose of Table 2-2 is to provide a basic description of what might be evident for each of the stages during the examination process. The examination items will not be discussed in detail because that would be beyond the scope and objective of this text. In the next section, however, we discuss in detail specific treatment guidelines for each of the stages. Understanding intervention strategies for each of the stages should enable the reader to more fully grasp the staging system and to appropriately progress patients during treatment.

TABLE 2-2 General Key Tests and Assessments for Staging

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 |

|---|---|---|

| PRECAUTIONS | ||

| SYSTEMIC SIGNS/SYMPTOMS | ||

| PAIN | ||

| NEUROLOGICAL STATUS | ||

| FUNCTION | ||

| ALIGNMENT | ||

| APPEARANCE | ||

| PALPATION | ||

| ROM | ||

| MUSCLE PERFORMANCE (RECRUITMENT/STRENGTH) | ||

AROM, Active range of motion; PROM, passive range of motion; ROM, range of motion.

Treatment Guidelines for Stages for Rehabilitation

With any patient, regardless of the stage at which he is initially diagnosed, the emphasis of treatment should be to restore range of motion (ROM) and strength of the involved segment, as well as the overall function of the individual without adding excessive stresses to the injured tissues. Specific movement impairments should also be addressed during rehabilitation to ensure optimal recovery and to promote proper performance of functional activities to prevent the recurrence of a specific injury or pain problem. General treatment guidelines are given for each stage and related to several key components of a rehabilitation program.

Precautions and Restrictions

Patients that present in Stage 1 may have had an acute injury or a recent surgery and often have restrictions or precautions in regard to movement or weight bearing that have been issued by the referring physician. Such orders serve to protect the injured tissue and to facilitate the recovery process. During the examination, the patient’s understanding of these precautions or restrictions needs to be assessed, and the patient’s ability to adhere to them needs to be determined. Precautions and restrictions should be strictly followed during the examination, and treatment options may be initially limited. Subsequent communication with the referring physician is important to progress the patient within an appropriate timeframe.

Patients that present in Stage 2 may or may not have physician-imposed precautions or restrictions still in place. Often, the progression to Stage 2 from Stage 1 is marked by a change in the degree of precautions or restrictions. For example, a postoperative patient might be progressed from non–weight-bearing status to 25 percent weight-bearing. In other cases, ROM restrictions may be progressed. Regardless of the restrictions or precautions ordered by the physician, patients in Stage 2 should be able to tolerate a certain amount of physical stress at the target tissues.

Patients that present in Stage 3 generally have no precautions or restrictions that would limit the progression of physical therapy. However, some individuals may enter Stage 3 with precautions or restrictions that will be in place for an extended period of time. Communication with the physician is important if any ongoing precautions or restrictions should be adhered to by the patient. If not, intervention can be progressed to gradually increase the amount of physical stress imposed on the involved tissues to increase the tolerance of the tissues.

Pain

Any pain complaint requires clarification of the location, quality, and intensity of the symptoms. This clarification enables the therapist to more accurately assess the actual source of pain and to develop an appropriate treatment plan that can then be progressed according to pain severity.

When treating an individual with pain, the therapist should consider the results of the assessment process to develop a staging diagnosis, as well as whether the patient presented to therapy after a surgical procedure or initiated therapy because of a pain problem or an acute injury. For the patient in Stage 1 who has had a recent surgery, some pain will likely be associated with exercises within the first 2 weeks of the postoperative period. Gradually over the next few weeks after surgery, pain associated with the exercise should lessen.

Pain can be used as a guide to the rehabilitation process. Sharp, stabbing pain should be avoided. Mild aching is expected after exercises but should be tolerable for the patient. This postexercise discomfort should decrease within 1 to 2 hours of the rehabilitation. Complaints of increasing pain, pain that is not decreasing with treatment, or burning pain are all indicators that the treatment is too aggressive or that there is a disruption in the usual course of healing. Coordinating the use of analgesics with exercise sessions may be beneficial. Splinting, bracing, and/or assistive devices may be used during this period to protect the injured tissue.

In contrast to the postsurgical patient, Stage 1 individuals with an acute injury or a pain problem should not reproduce their pain with exercise. Modalities, such as ice or electrical stimulation, and external support, such as taping or bracing, may be helpful to decrease pain.26-29 The patient may also require the use of an assistive device during the early phases of healing.

The specific tissue pain present during Stage 1 should be significantly decreased for patients that present in Stages 2 or 3. However, as the treatment for the patient is progressed, he or she may report increased pain or discomfort with higher level exercises, fitness activities such as walking or running, and return to the previous work or sport intensity. Thus the location of pain and discomfort should be closely monitored. Muscle soreness is expected, similar to the response of muscle to an overload stimulus (i.e., weight training). Usually, general muscle soreness should be allowed to resolve within 1 to 2 days before repeating a specific bout of activity. Pain described as stabbing should always be avoided.

Edema

Edema is quite common after surgery or an acute injury. Therefore the Stage 1 patient should be specifically educated in the use of edema control. Techniques that can safely be used during Stage 1 to control edema include the following:

The patient should be encouraged to keep the extremity elevated as much as possible, particularly in the early phases (1 to 3 weeks). Application of ice after exercise is generally recommended. Ideally, a measurement of the edema should be taken at each visit to gauge progress. A sudden increase in edema may indicate that the rehabilitation program is too aggressive or that a possible infection has started. If an infection is suspected, the physician should be contacted immediately.

The time it takes for edema around the involved tissue to resolve is variable among patients and surgical procedures. Although edema should decrease significantly in the first 2 to 4 weeks after surgery or injury, some edema may persist for several months. Thus care should be taken to continually manage edema for individuals in Stages 2 and 3. As noted previously, techniques such as icing, elevation, and compression may be used successfully after exercise to minimize potential swelling with new or higher level activities. Additionally, Stages 2 and 3 patients might need to be instructed on how to moderate and progress their activity level. If activities and exercises are progressed appropriately, the edema should continue to decrease gradually with time.

Appearance

After surgery, the area around the incision or the involved joint should be closely monitored for a developing infection. An infection should be suspected if the involved area appears to be red, hot, and swollen. As noted previously, the physician should be consulted immediately if infection is suspected. An infection is most likely to occur during Stage 1 rehabilitation, but the patient should be monitored throughout the rehabilitation process.

Bruising after surgery or after a traumatic injury is common, and the patient should be monitored continually for any changes suggesting bruising. Again, an increase in bruising during the rehabilitation process may indicate an infection or additional injury.

Consideration should also be given to changes in hair growth, perspiration, or color because such symptoms may indicate some disturbance to the sympathetic nervous function, especially if in combination with the complaint of excessive pain.

During Stages 2 and 3, the incision should be well healed. Although bruising may still be present, it should be diminishing. As with Stage 1, signs of increased bruising or changes to the incision site are indicators of an adverse response to exercise or activity and the patient should be immediately referred to the physician.

Scar

Although scarring is a normal process of healing, it must be managed well during the rehabilitation process, particularly for the patient in Stage 1. Exercise, massage, compression, silicone gel sheets, and vibration are commonly used for scar management, although the use of silicone gel is best supported by the evidence.31,32

The gradual application of stress to the scar or incision site helps the scar remodel to allow the necessary gliding between tissue structures. A dry incision that has been closed and reopens as the result of the stresses applied with scar massage indicates that the scar massage is too aggressive. Additionally, a hypersensitive scar will require some level of desensitization.

A scar may continue to remodel for up to 2 years. Although they are probably most effective early in the healing process, scar management techniques may be effective until the scar matures. Therefore patients in Stages 2 and 3 may also benefit from education on scar management.

Range of Motion

ROM is often an important component of treatment for the patient in Stage 1. Depending on the type of injury, the patient may have ROM precautions or restrictions per the physician’s orders to protect the healing tissues. If so, splinting or bracing is commonly used to adhere to the ROM precautions while allowing for the initiation of exercise as soon after surgery as possible.

Early initiation of ROM exercises is important to prevent muscle contracture or loss of flexibility as a result of immobilization.33,34 In the early stages of rehabilitation, the patient should perform ROM exercises multiple times a day, and all exercises should be performed within pain tolerance. The uninvolved joints should also be exercised to prevent the development of restricted ROM at those joints. Decreasing pain and edema and improving ROM are typical indicators that the exercises can safely be progressed.

The typical exercise progression begins with gentle passive ROM and progresses gradually to active-assisted ROM (AAROM) and AROM; however this may vary in cases of injury to muscle or tendon. If resistance is allowed, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) techniques, such as contract-relax or hold-relax, can be used to achieve ROM goals. If these techniques are used in Stage 1, the applied resistance should be gentle.

When performing ROM exercises near a fracture site, special attention should be given to hand placement during the exercises to minimize the stresses placed on the healing fracture site.

For patients in Stages 2 and 3, ROM precautions or restrictions have generally been reduced or lifted altogether. ROM in each of the stages, particularly Stage 2, may still be limited. However, exercise to increase ROM should be progressed and made more aggressive to achieve normal or functional range if appropriate.

Finally, joint mobilization may be a useful technique for any of the stages to facilitate an increase in ROM.34 However, the physician should be consulted before initiating joint mobilization after a fracture or a specific joint injury.

Strength or Muscle Performance

For patients in Stage 1, strengthening or resistance training often does not begin until after the initial phase of healing (4 to 6 weeks). Thus the emphasis of treatment for these patients is on education, immobilization, edema management, and gradual progression of ROM with the correct movement pattern. Occasionally, light resistance is applied during exercises to improve the recruitment pattern of a specific muscle or muscle group, but such exercises should not be used to overload and strengthen the involved muscles. Also, if light resistance exercises are used, they should not violate any precautions or restrictions set forth by the physician.

Approximately 4 to 6 weeks after the surgery or the injury, strengthening may be gradually incorporated into the intervention program. By this time, patients have general progressed into either Stage 2 or Stage 3. Progression to a resistive exercise program is based on the patient’s ability to perform ROM with a good movement pattern and without a significant increase in symptoms. For patients in Stages 2 and 3, weights, elastic bands, or isokinetic equipment may be used to enhance muscle performance. Specific exercise protocols provided by physicians and physical therapists should be evaluated to ensure that all exercises are appropriate for the individual’s situation. Electrical stimulation or biofeedback may also be used to increase muscle strength and to improve motor recruitment.35-38

Proprioception and Balance

Proprioception and balance39 are important components of fitness that can be incorporated into a rehabilitation program to improve functional activity performance and to hasten the return to high-level work or sport activities. Consideration of weight-bearing and ROM precautions or restrictions must be made for the patient in Stage 1. Therefore the initiation of these types of activities during Stage 1 might vary according to the body region involved, the surgical procedure performed, or the injury incurred.

During Stages 2 and 3, proprioception and balance activities should be prescribed gradually to ensure proper postural control and patient safety. These exercises can be modified as necessary to incorporate any remaining precautions or restrictions. As the patient progresses into and through Stage 3, the balance and proprioceptive exercises prescribed by the therapist should be relevant to the sport, work, or functional activity that the patient needs to perform.

Cardiovascular Endurance

If not contraindicated by co-existing medical complications or specific precautions or restrictions, cardiovascular endurance activities should begin as soon as possible. During Stage 1, aerobic activities may need to be performed at a relatively low intensity and for a short duration. Thus these individuals may benefit from more frequent performance of cardiovascular exercises.40 Interestingly, patients at any stage performing cardiovascular endurance exercises may have the added benefit of reduced pain and increased feelings of well-being.40,41

In Stages 2 and 3, the intensity, duration, and frequency of the exercise can be progressed as tolerated. For athletes, the cardiovascular exercises prescribed should be relevant to their sport or training regiment. For other patients interested in fitness, the cardiovascular exercise program should be tailored to prevent the potential onset of symptoms, to encourage correct movement patterns, and to promote optimal compliance.

Mobility

Early functional use of the injured segment should be encouraged while protecting the healing tissue. Educate the patient regarding precautions/restrictions, the use of the involved extremity during activities of daily living (ADLs), and the use of an appropriate assistive device as needed, including braces or splints. Compensatory techniques for mobility may be required during Stage 1 to protect the involved tissue and to promote optimal function. As precautions/ restrictions allow, the patient should be instructed on the proper way to perform common functional mobility tasks using more normal, essential component-based strategies for movement. In addition, the assistive device used by the patient should be modified or eliminated according to the improvement in the patient’s condition.

Work/School/Higher Level Activities

A patient in Stage 1 may be off work or restricted from regular activities during the immediate postoperative period or after an acute injury. When the patient is cleared to return to work or sport, he or she should be instructed in a gradual resumption of normal activities. The patient in Stage 1 who is required to return to work may benefit from instruction in specific modifications to the environment, or from imposed restrictions for light or limited duty. While at work, the patient should emphasize edema control and pain management. The goal is to prevent re-injury of the involved tissue.

A patient in Stage 2 may still have restrictions or limitations imposed for work or school activities. However, an effort should be made in therapy, if appropriate, to return the patient to his or her prior level of function at work or with a specific sports activity. Specifically, education about and practice of specific work or sport activities should be included in the intervention program. Edema and pain management should continue to be emphasized, in addition to the treatment of specific movement impairments related to deficits in muscle performance, joint mechanics, flexibility, or balance.

Finally, a patient in Stage 3 should be able to fully return to work or sport activities. In this stage, additional physical stress is applied during therapy to improve the ability of the patient to perform such higher level activities correctly for the necessary amount of time. Pain control and edema management may still be necessary, but the emphasis of treatment is on the optimal performance of the work or sport activity specific to the patient.

Sleep

Sleep is often disrupted in the immediate postoperative period or after an acute injury. During Stage 1, the patient should avoid sleep positioning that may encourage increased edema or possible contracture of the involved segment. For all stages, the patient should be educated on optimal sleep positions to reduce prolonged stress to the involved body regions. To fully correct a patient’s sleep posture, regardless of stage, external supports, such as pillows or towels, may be used.

External Support

After surgery, the patient in Stage 1 may need to use a splint or a brace to protect the surgical site, depending on the specific surgical procedure or the type of injury sustained. During treatment, the therapist should ensure that the brace or splint fits the patient comfortably. The patient should also be educated in the timeline for wearing the brace. If the wearing time is not clear, the therapist should refer to the specific protocol prescribed by the physician or consult with the physician if no specific orders are provided.

A splint or brace might also be necessary for a patient who has sustained an acute injury. In addition, taping techniques may be used as an adjunct to treatment to help decrease symptoms and to control movement, depending on the underlying movement impairment.42-45

The recommendations concerning the need for splinting, bracing, or taping for prolonged periods are varied. Therefore communication among the physician, the patient, and the physical therapist is essential to determine the need for external support for the Stage 2 or Stage 3 patient.

Medications

During Stage 1, physical therapy could be timed with analgesic administration if possible, which should typically be 30 minutes after the administration of an oral medication. Communication with nurses and physicians is critical to ensure optimal pain relief for the patient. Otherwise, medications for patients in all stages should be reviewed to ensure that they are being taken appropriately. The therapist should be aware of any potential side effects of the medications that the patient is taking so that any problems that develop will be easily recognized and any impact on the treatment or the performance of daily functional activities can be minimized.

Modalities

For patients in all stages, modalities or physical agents can be used for pain relief, edema control, strengthening, and flexibility. For example, interferential current and sensory level transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TENS) has been shown to be helpful in decreasing pain and edema.46-48 There is also some evidence to suggest that ultrasound can be used to enhance tissue healing49-51 or to improve tissue extensibility through deep heating.52 Finally, electrical stimulation is commonly used for muscle strengthening. Recent studies support the use of electrical stimulation to improve both motor recruitment and strength.35-37 Regardless of the modality chosen, the therapist should determine if the patient is appropriate for a specific modality and check to ensure that there are no contraindications. Also, the therapist should be aware of specific precautions for each type of modality with regard to application. Ultimately, modalities can be a useful adjunct to treatment at any stage, but they should not be used alone.

Patient Education

Regardless of the stage for rehabilitation, patient education is an essential aspect of the treatment program. Therefore the following educational principles should be incorporated into the treatment of patients as appropriate. First, educate the patient regarding the structure and tissues involved in the injury, pain problem, or surgical procedure, as well as the approximate timeline for recovery and return to activity. Often, the patient will also need additional instructions regarding specific medical or surgical precautions ordered by the physician. Specifically, the patient should be instructed on how to maintain the prescribed precautions during various functional activities such as ambulation and transfers. If the patient has or obtains a brace or a splint, the patient should be educated on specific donning and doffing procedures, a schedule for use, and the appropriate care of the device. Finally, if appropriate, the patient should be educated regarding any specific movement impairment he or she might have and on how to move correctly throughout all daily activities and exercises.

Changes in Status

For each stage, the therapist should carefully consider patient reports of increased pain or edema, decreased strength, or a significant change in ROM, especially if any of these occur in combination. The patient should be questioned about any precipitating factors related to the change in status (i.e., time of onset, daily activities performed before onset).

If the patient is postsurgical and the integrity of the surgery is in doubt, contact the physician promptly, particularly if there is fever and erythema observed at the incision site, which might indicate a potential infection.

In the next section, the diagnostic and treatment process is discussed with regard to the stages for rehabilitation. In doing so, we address how changes in patient status may affect the physical therapist’s decision-making strategy and ultimately specific patient intervention.

The Diagnostic Process

When performing an evaluation of the movement system, the physical therapist should be able to recognize the potential source of symptoms or the biological tissues involved. More importantly, however, the therapist should attempt to determine the actual cause of the patient’s symptoms by using a thorough examination of a patient’s movement and posture. In doing so, a movement system diagnosis that can be used to develop a treatment plan and to progress the patient appropriately can be established.

Often, the cause of symptoms cannot be determined because of acuity or because a movement impairment simply does not exist. In either case, as shown in Table 2-3, the physical therapist should be able to establish a source or regional impairment diagnosis that can be used to treat the patient. Regardless of the diagnosis established, staging for rehabilitation should be an integral part of the diagnostic process for physical therapy. An understanding of this process should enable both the novice and expert physical therapist to implement a logical system for patient evaluation and re-evaluation to prescribe an optimal treatment program and to modify the intervention plan as needed.

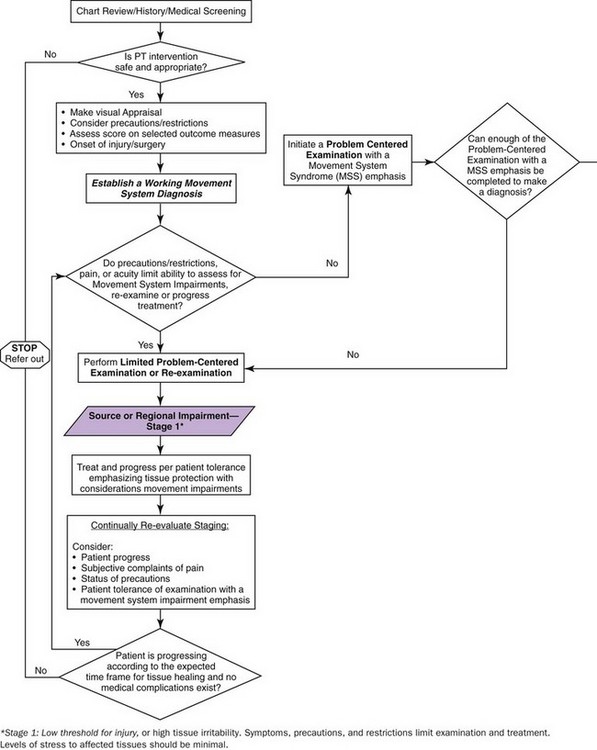

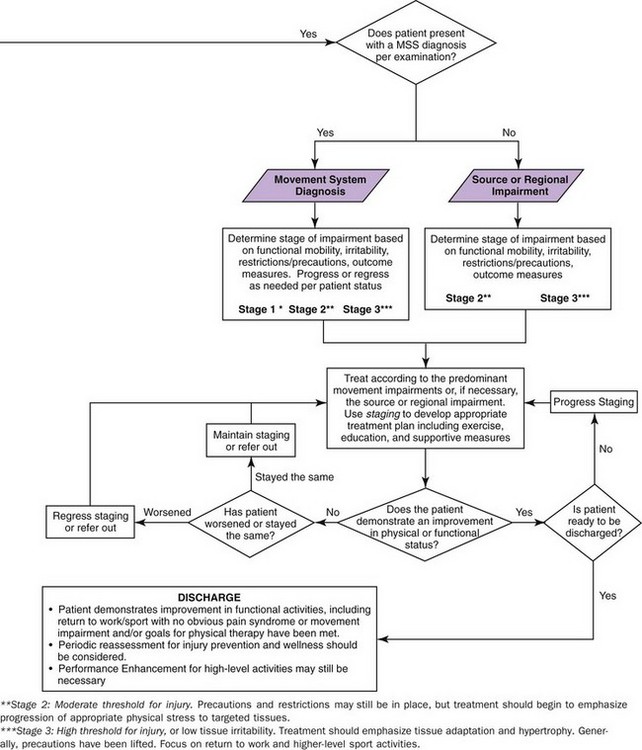

Figure 2-2 illustrates the movement system evaluation process. This diagram presents a series of questions and steps that can be used to establish a diagnosis with a specific stage and illustrates the diagnostic process that more specifically demonstrates the use of staging. Rather than describe each step in detail, the following three cases demonstrate the decision-making processes used by expert clinicians to determine a movement system diagnosis and to stage the affected tissues. Figure 2-2 can be used to follow the decisions made for each case.

Figure 2-2 The movement system evaluation process. According to the physical stress theory, the stages used within the flow chart can generally be defined by stress restriction/progression. Staging should continually be evaluated. PT, Physical therapy.

With any diagnosis that is established using the algorithm in Figure 2-2, it is important to continually re-evaluate the patient and modify the diagnosis, staging, or treatment as needed. At any time during a patient intervention, staging and the associated treatment can be progressed, regressed, or discontinued. In addition, the actual diagnosis may change if an impairment of the movement system develops. Thus the diagnostic process presented here should serve as a guide for the therapist to follow to establish an accurate diagnosis and an effective treatment plan, but the therapist must recognize the fluidity of this process to use it successfully.

Case Presentation

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

Symptoms and History

A 28-year-old female patient presents to an outpatient physical therapy clinic 2 days after an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction using a patellar tendon graft, in addition to a repair of the lateral meniscus. Surgical protocols following an ACL reconstruction vary across regions of the country and across physicians, but for the purposes of this case, the patient was weight bearing as tolerated for the first 6 weeks after the surgery with a hinged brace locked into full extension for all weight-bearing activities. The patient was using bilateral axillary crutches for ambulation. No ROM restrictions or precautions were ordered by the physician, but resisted testing of the involved quadriceps was contraindicated.

A history and medical screening using the movement system evaluation process to guide the initial visit is performed. The patient is medically stable and safe to treat, thus a working movement system or source diagnosis should be established. The working diagnosis is based on the information learned from the history, including the date of surgery; the results of standardized outcome measures to assess overall level of function, visual appraisal of the patient, and knowledge of specific precautions and restrictions. The working diagnosis helps guide the examination process to ensure that the appropriate tests are used and the patient is not subjected to re-injury. In this case, a working movement system diagnosis cannot be established. Rather, based on her presentation, a working diagnosis of a Stage 1 Knee Impairment would be more appropriate.

Key Tests and Signs

Precautions, restrictions, pain, and acuity limit the tests that can be used to assess for specific movement system impairments. Therefore, a limited problem-centered evaluation is performed that emphasized measurement of ROM and edema, assessment of functional activities such as gait and transfers, and visual observation of the incision site. Certainly, other tests and measures may be incorporated, but the therapist should recognize when certain movement tests should not or cannot be performed. For any test or measurement performed during the limited problem-centered evaluation, the therapist should note any observed movement faults that might be related to an underlying movement system diagnosis. For example, if the patient in this case were to demonstrate femoral adduction/medial rotation or tibial lateral rotation during the assessment of knee flexion ROM, the therapist considers a working movement system diagnosis of tibiofemoral rotation syndrome.

Diagnosis and Staging

Based on the results of the examination, the patient is given a diagnosis of ACL and lateral meniscal tear, s/p ACL reconstruction with lateral meniscal repair, Stage 1. By convention, neither symptoms nor a specific procedure should be used as the actual diagnosis. In this example, ACL and lateral meniscal tear is the actual diagnosis. This is the source diagnosis provided by the physician and is based on the tests the physician can perform or order. The inclusion of the surgical procedure (ACL reconstruction with lateral meniscal repair) and the stage for rehabilitation in the diagnosis provides additional information to describe the patient’s status and to direct the development of a treatment program. Note that if no specific physician’s or source diagnosis is provided, the physical therapist should name the diagnosis according to the region that is impaired. For example, if the patient had been seen prior to being diagnosed with the ACL tear, the diagnosis would be knee impairment, Stage 1. In the next two cases, we will review the diagnostic naming procedures.

Treatment

Once a diagnosis has been established, the physical therapist can initiate treatment. For this patient with a Stage 1 condition, the emphasis of treatment is on tissue protection. However, the therapist should always be aware of specific movement impairments that become evident during low-level exercise and activity. For this case, the actual treatment provided is not discussed because the primary objective here is to illustrate the diagnostic process. Once a patient has begun treatment, the therapist should continually re-evaluate the level of staging. In doing so, the physical therapist should consider patient progress, pain complaints, the status of precautions or restrictions, and patient tolerance of an examination with a movement system syndrome emphasis.

The patient progressed according to the expected timeframe for tissue healing, and after 6 weeks, when she was able to unlock her brace, she was able to be examined using a complete a problem-centered evaluation with a movement system syndrome emphasis.

Based on her complaints of pain and specific movement impairments, the patient is given a diagnosis of tibiofemoral rotation with secondary patellar lateral glide syndrome s/p ACL reconstruction and lateral meniscal repair, Stage 2 (see Chapter 7). The stage was determined based on considerations of her overall level of pain, the time since her surgery, the progress noted in ROM and functional activity performance, and the elimination of all restrictions.

Once the diagnosis is made, treatment is progressed to address the specific movement impairments and to increase the adaptive physical stress applied to the tissues that were initially weakened by both the injury and the surgery. As expected, during a thorough re-examination 6 weeks later, the patient demonstrated continued improvement, reporting minimal pain and demonstrating normal ROM and adequate quadriceps performance. However, she was still not ready for discharge because she had not started to run. Therefore her staging was progressed to Stage 3, and her treatment was modified accordingly to include higher-level activities such as running and jumping.

Staging is somewhat unique to each individual. In this case, the patient was young and athletic with specific fitness and sports-related goals. Therefore, to ensure completion of these goals, treatment during Stage 3 was rather aggressive and discharge occurred when those goals were achieved. For other patients, the specific Stage 3 goals and subsequently, the intensity of treatment may differ based on such factors as age, medical co-morbidities, or prior level of function, but the completion of these goals is necessary for discharge.

Case Presentation

Chronic Lower Back Pain

Symptoms and History

A 42-year-old male presents to physical therapy with chronic lower back pain. The patient reports an insidious onset of pain 8 months ago that has gradually worsened. The patient’s symptoms are localized to his right lower back with no radiating symptoms. The patient notes that on average his pain is about a 4/10 with an Oswestry score of 22%. Although he has some pain throughout the day, he continues to perform all of his daily activities, including his work responsibilities that are mostly sedentary. However, the patient has increased pain with running and with racquetball and is therefore no longer participating in these activities.

Key Tests and Signs

After a medical screening, including a brief review of systems, the determination is made that it is safe to proceed with evaluation and treatment. Based on the history provided, visual observation and the Oswestry score, a working diagnosis of lumbar rotation is established. The patient has no precautions, and his current symptoms will not limit the performance of the standard movement system examination.

Diagnosis and Staging

After a thorough movement system examination, the patient is diagnosed with lumbar rotation syndrome, Stage 2. The stage was determined by multiple factors discussed previously, including the time since the onset of pain, the relatively low pain level and Oswestry score, his functional activity performance, and his current limitations.

Treatment

Although this patient has a moderate level of tissue irritability, he should be able to accept some level of adaptive physical stress with treatment. Since a movement system diagnosis is established, treatment emphasizes the correction of specific movement faults or incorrect postures with exercise and education. Thus treatment is based on both the movement system diagnosis, as well as the stage for rehabilitation.

Outcome

As the patient improves and his tissue irritability decreases, he can be progressed to Stage 3 and then treated accordingly. Treatment for lumbar rotation syndrome, Stage 3 includes exercise and education to improve tolerance of higher level sport activities such as running and racquetball. Once the patient is able to return to these activities and manage his pain, he will be discharged.

Case Presentation

Moderate Ankle Sprain

Symptoms and History

A 16-year-old male basketball player presents to physical therapy after a moderate ankle sprain 6 months ago. During the history, the patient notes only moderate and infrequent pain in the lateral aspect of his ankle. His primary complaint is stiffness that is limiting his mobility during running and cutting activities. His score on the Foot and Ankle Ability Measure (FAAM) activities of daily living (ADLs) subscale is 92%, whereas his score on the FAAM sports subscale is only 72%. The physician provides a prescription for physical therapy to evaluate and treat ankle pain.

Key Tests and Signs

After a medical screening and a thorough history, the therapist determines that it would be safe to proceed with the evaluation to confirm a working diagnosis of ankle impairment. Because the patient has minimal pain and because the injury is not acute, the examination is not limited.

Diagnosis and Staging

According to the results of a thorough movement system examination, the patient does not present with any obvious or consistent movement impairments. For this reason, the patient is diagnosed with Ankle Impairment.

Again, staging for this patient is determined by the time since the initial injury, pain, functional activity level, and the functional outcome measure.

This patient is functioning at a high level and demonstrates a low level of tissue irritability, both of which are associated with Stage 3.

Treatment

The emphasis of treatment is on aggressive ROM techniques to decrease hypomobility and sports-specific training to optimize performance.

Although this patient was not initially diagnosed with a movement system diagnosis, it is still important to attend to the patient’s movements and posture during functional activities and exercise to ensure that he does not develop any faulty movements during the rehabilitation process or with the return to sport after an injury.

Conclusion

As the previous case studies illustrate, the diagnostic process is both complex and continual. Consideration of the actual tissues involved in a specific musculoskeletal pain problem is essential for this process to occur appropriately without risk to the patient. Attending to the Stage for Rehabilitation allows the therapist to incorporate or exclude certain examination items, to emphasize specific educational principles, and to develop an appropriate treatment strategy. In addition, by understanding the state of the specific source of symptoms, you are more likely to positively affect the actual cause of symptoms. Throughout the remainder of this book, you will be introduced to many diagnoses related to movement system syndromes, otherwise referred to as the potential cause of symptoms. The Stages for Rehabilitation should be used with each of these diagnoses to successfully develop, modify, and progress a treatment program that is designed to ultimately optimize patient outcomes.

1 Garrett WE. Muscle strain injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1964;24(Suppl 6):S2-S8.

2 Yarasheski KE, Pak-Loduca J, Hasten DT, et al. Resistance exercise training increases mixed muscle protein synthesis rate in frail women and men > 76 years old. Am J Phys. 1999;277:E118-E125.

3 Fitts RH, Riley DR, Widrick JJ. Physiology of a microgravity environment invited review: microgravity and skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:143-152.

4 Trappe S, Williamson D, Godard M, et al. Effect of resistance training on single muscle fiber contractile function in older men. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:143-152.

5 Yu ZB, Gao F, Feng HZ, et al. Differential regulation of myofilament protein isoforms underlying the contractility changes in skeletal muscle unloading. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;92(3):C1192-C1203.

6 Terzis G, Stattin B, Holmberg HC. Upper body training and the triceps brachii muscle of elite cross country skiers. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2006;16(2):121-126.

7 Crameri RM, Cooper P, Sinclair PJ, et al. Effect of loading during electrical stimulation training in spinal cord injury. Muscle Nerve. 2004;1:104-111.

8 Starkey DB, Pollock ML, Ishida Y, et al. Effect of resistance training volume on strength and muscle thickness. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28(10):1311-1320.

9 Turner CH. Three rules for bone adaptation to mechanical stimuli. Bone. 1998;23:399-407.

10 Holick MF. Perspective on the impact of weightlessness on calcium and bone metabolism. Bone. 1998;22:105S-111S.

11 Notomi T, Lee SJ, Okimoto N, et al. Effects of resistance exercise training on mass, strength, and turnover of bone in growing rats. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2000;82:268-274.

12 Leblanc AD, Schneider VS, Evans HJ, et al. Bone mineral loss and recovery after 17 weeks of bed rest. J Bone Miner Res. 1990;8:843-850.

13 Schroeder ER, Wiswell RA, Jaque SV, et al. Eccentric muscle action increases site-specific osteogenic response. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(9):1287-1292.

14 Wren TA, Beaupre GS, Carter DR. A model for loading-dependent growth, development, and adaption of tendons and ligaments. J Biomech. 1998;31:107-114.

15 Hayashi K. Biomechanical studies of the remodeling of knee joint tendons and ligaments. J Biomech. 1996;29:707-716.

16 Woo SL, Gomez MA, Akeson WH. Mechanical properties of tendons and ligaments. II. The relationships of immobilization and exercise on tissue remodeling. Biorheology. 1982;19(3):397-408.

17 Mueller MJ, Maluf KS. Tissue adaptations to physical stress: a proposed “Physical Stress Theory” to guide physical therapist practice, education, and research. Phys Ther. 2002;4:383-403.

18 Sahrmann SA. Diagnosis and treatment of movement impairment syndromes. St Louis: Mosby; 2002.

19 Pressure ulcers in adults: prediction and prevention, AHCPR Publication No. 92-0047, Rockville, MD, 1992, US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS).

20 Johnson KA, Strom DE. Tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction. Clin Orthop. 1989;239:196-206.

21 Pang HN, Teoh LC, Yam AK, et al. Factors affecting the prognosis of pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1742-1748.

22 Burkhead WZ, Arcand MA, Zeman C, et al. The biceps tendon. In Rockwood CJr, Matsen FAIII, editors: The shoulder, ed 2, Philadelphia: Saunders, 1998.

23 Neer CS. Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:41-50.

24 Peterson HA. Physeal fractures. Part 3. Classification. J Pediatr Orthop. 1994;14(4):439-448.

25 Delitto A, Erhard RE, Bowling RW. A treatment-based classification approach to low back syndrome: identifying and staging patients for conservative treatment. Phys Ther. 1995;21:381-388.

26 Michlovitz SL. Thermal agents in rehabilitation, ed 3. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 1996.

27 Robinson AJ. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for the control of pain in musculoskeletal disorders. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1996;24:208-226.

28 Johnson MI, Ashton CH, Thompson JW. An in-depth study of long-term users of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. Pain. 1991;44:221-229.

29 Johnson MI, Tabasam G. An investigation into the analgesic effects of interferential currents and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on experimentally induced ischemic pain in otherwise pain-free volunteers. Phys Ther. 2003;83:208-223.

30 Lessard L, Scudds R, Amendola A, et al. The efficacy of cryotherapy following arthroscopic knee surgery. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1997;26:14-22.

31 Reish RG, Eriksson E. Scars: A review of emerging and currently available therapies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1068-1078.

32 Mustoe TA, Cooter RD, Gold MH, et al. International clinical recommendations on scar management. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:560-571.

33 Donatelli R, Owens-Burckhart H. Effects of immobilization on the extensibility of periarticular connective tissue. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1981;3:67-72.

34 Kisner C, Colby LA. Therapeutic exercise: foundations and techniques. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 2007.

35 Delitto A, Rose SJ, Lehman RC, et al. Electrical stimulation versus voluntary exercise in strengthening the thigh musculature after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Phys Ther. 1998;68:660-663.

36 Fitzgerald GK, Piva SR, Irrgang JJ. A modified neuromuscular electrical stimulation protocol for quadriceps strength training following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33:492-501.

37 Stevens JE, Mizner RL, Snyder-Mackler. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation for quadriceps muscle strengthening after bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34:21-28.

38 Draper V. Electromyographic biofeedback and recovery of quadriceps femoris muscle function following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Phys Ther. 1990;70:11-17.

39 Hewett TE, Paterno MV, Myer GD. Strategies for enhancing proprioception and neuromuscular control of the knee. Clin Orthop. 2002;1:76-94.

40 American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000.

41 Suomi R, Collier D. Effects of arthritis exercise programs on functional fitness and perceived activities of daily living measures in older adults with arthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1589-1594.

42 Warden SJ, Hinman RS, Watson MAJr, et al. Patellar taping and bracing for the treatment of chronic knee pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:73-83.

43 Selkowitz DM, Chaney C, Stuckey SJ, et al. The effects of scapular taping on the surface electromyographic signal amplitude of shoulder girdle muscles during upper extremity elevation in individuals with suspected shoulder impingement syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37:694-702.

44 Hyland MR, Webber-Gaffney A, Cohen L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of calcaneal taping, sham taping, and plantar fascia stretching for the short-term management of plantar heel pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:364-371.

45 Crossley K, Bennell K, Greeen S, et al. Physical therapy for patellofemoral pain: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:857-865.

46 Christie AD, Willoughby GL. The effect of interferential therapy on swelling following open reduction and internal fixation of ankle fractures. Physiother Theory Pract. 1990;6:3-7.

47 Johnson MI, Wilson H. The analgesic effects of different swing patterns of interferential currents on cold-induced pain. Physiotherapy. 1997;83:461-467.

48 Young SL, Woodbury MG, Fryday-Field K. Efficacy of interferential current stimulation alone for pain reduction in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized placebo control clinical trial. Phys Ther. 1991;71:252.

49 Binder A, Hodge G, Greenwood M, et al. Is therapeutic ultrasound effective in treating soft tissue lesion? Br Med J. 1985;290:512-514.

50 Ebenbichler GR, Erdogmus CB, Resch KL, et al. Ultrasound therapy for calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1533-1538.

51 Enwemeka CS. The effects of therapeutic ultrasound on tendon healing. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1989;6:283-287.

52 Wessling KC, DeVane DA, Hylton CR. Effects of static stretch versus static stretch and ultrasound combined on triceps surae muscle extensibility in healthy women. Phys Ther. 1987;67:674-679.