Chapter 5 Appendix

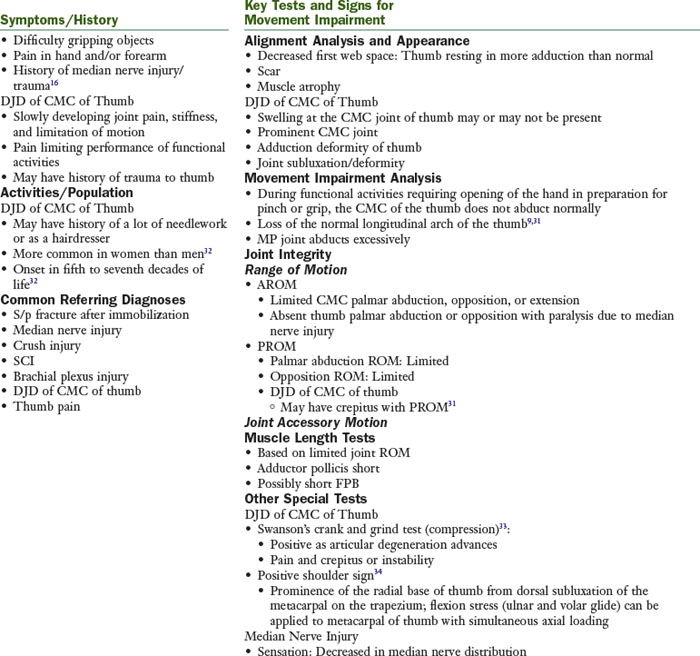

Insufficient Finger and/or Thumb Flexion Syndrome

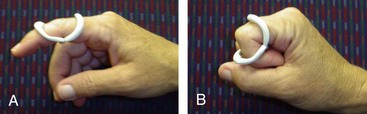

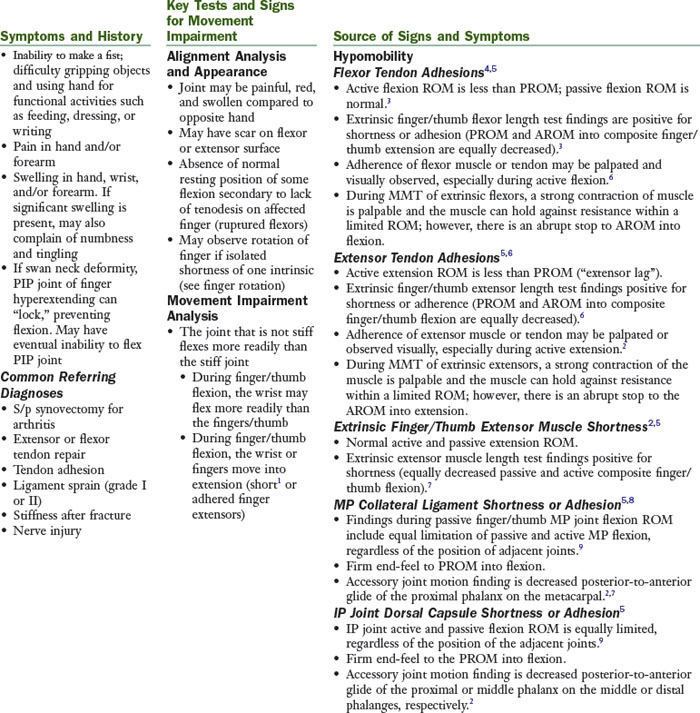

The principal impairment in insufficient finger and/or thumb flexion syndrome is limited finger or thumb flexion AROM, but the key to prescribing the appropriate interventions is differentiating between the sources causing the limited flexion. The sources of the limited flexion can be broadly classified into two main categories: hypomobility (physiological and accessory motion) or force production deficit (decreased strength). Insufficient finger and/or thumb flexion syndrome is most commonly secondary to a trauma or injury or after a period of immobilization to allow for tissue healing. Initially, these patients may be assigned a movement system diagnosis of hand impairment Stage 1, but an underlying movement system diagnosis of insufficient finger and/or thumb flexion syndrome may help guide treatment. As the tissues heal, the diagnosis may change from hand impairment to another movement system diagnosis such as insufficient finger and/or thumb flexion syndrome. The “Source of Signs and Symptoms” column provides key information regarding the cluster of findings identifying the source of the limited flexion. The identified source or cause of insufficient finger and/or thumb flexion comprises the second part of the name of the syndrome.

Treatment

See Box 5-2 for treatment of scar and edema. The usual expectation is that AROM should increase by a minimum of 10 degrees per week except when the cause of the limitation is due to profound weakness or rupture. Pain and edema should decrease gradually over the course of treatment. The therapist must avoid applying excessive force when performing passive stretching exercises on patients that have hand injuries. Overly aggressive exercise increases swelling and may result in increased fibrosis and limitation of ROM.

Treatment for Insufficient Finger and/or Thumb Flexion Syndrome Caused by Flexor Tendon Adhesion

Treatment of adhesions requires active and resistive contraction of flexors and stretching into composite extension (see Box 5A-1 for General Guidelines for Treatment Progression).

Figure 5A-1 Direction of tendon glide. Flexor tendon glides proximally with active flexion. Flexor tendon glides distally with active or passive finger extension.

(From Interactive Hand 2000, Copyright 2001.)

Figure 5A-2 Composite stretching fingers and wrist into extension for distal gliding of adhered finger flexor tendons or lengthening the finger flexors. A, Manual stretching using opposite hand. B, Stretching with assist of splint to maintain finger extension.

(Used with permission from Ann Kammien, PT CHT, St Louis, Mo.)

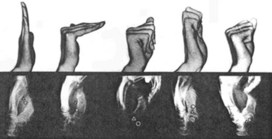

Figure 5A-3 Flexor tendon gliding exercises. Straight fist: FDS glides maximally with respect to sheath and bone. Hook fist: Maximum gliding between FDS and FDP. Fist: FDP glides maximally with respect to sheath and bone.

(Reprinted from Wehbe MA, Hunter JM: Flexor tendon gliding in the hand. II. Differential gliding, J Hand Surg 10A:575-579, 1985.)

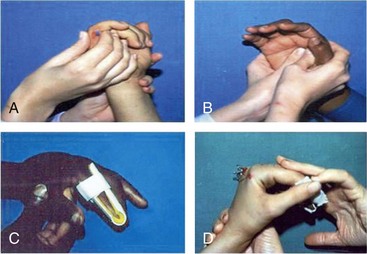

Figure 5A-4 Active finger flexion exercises to increase flexor tendon gliding proximally. A, Active braced or blocked DIP flexion to increase gliding of flexor digitorum profundus. B, Use of thermoplastic splint to isolate movement to DIP joint and block PIP and MP joint motion. C, Use of Bunnell block to isolate DIP flexion. D, Active braced or blocked PIP flexion to increase gliding of flexor digitorum superficialis. E, Exercising flexor digitorum superficialis by actively flexing middle finger PIP joint, preventing flexor digitorum profundus from working by stabilizing other fingers in extension. F and G, Use of thermoplastic splints to isolate movement to PIP joint and block MP joint motion.

(Used with permission from Ann Kammien, PT CHT, St Louis, Mo.)

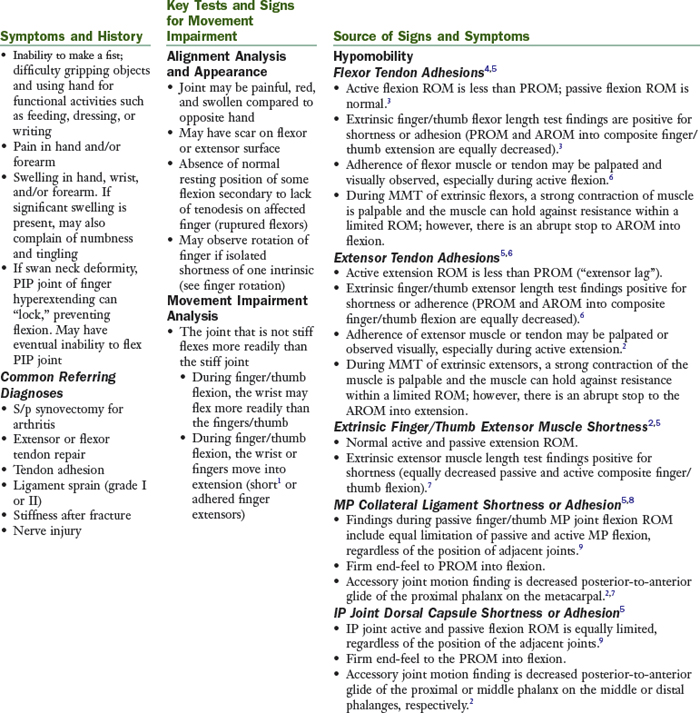

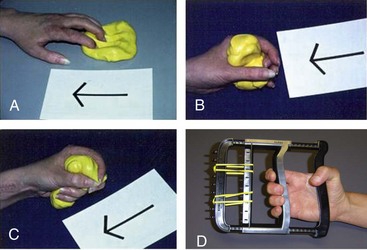

Figure 5A-5 Resistive finger flexion exercises to increase proximal tendon gliding of the finger flexors. A, Finger flexion into putty resting on table. B, Composite finger flexion done incorrectly: Involved index finger is not touching putty. C and D, Composite finger flexion done correctly with putty and hand gripper, respectively, resisting involved index finger.

(A to C, Used with permission from Ann Kammien, PT CHT, St Louis, Mo.)

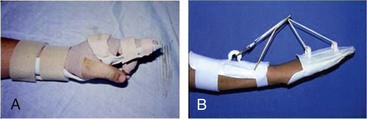

Figure 5A-6 Splinting for insufficient finger flexion caused by flexor shortness or adhesions. A, Static splint to maintain wrist and fingers at end-range extension used at night. B, Static progressive or dynamic splint to increase composite wrist and finger extension.

(Used with permission from Ann Kammien, PT CHT, St Louis, Mo.)

Treatment for Insufficient Finger and/or Thumb Flexion Syndrome Caused by Extensor Tendon Adhesions/Extrinsic Extensor Muscle Shortness

Treatment of both shortness and adhesion requires stretching into composite flexion. Treatment of adhesions only requires active and resistive contraction of extensors.

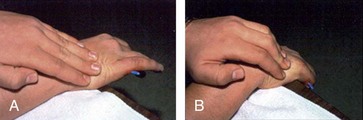

Figure 5A-7 Massage for Insufficient finger flexion caused by extensor tendon adhesions. A, Pushing scar distally the opposite direction of the tendon glide during active finger extension. B, Pushing scar proximally during active finger flexion.

(Used with permission from Ann Kammien, PT CHT, St Louis, Mo.)

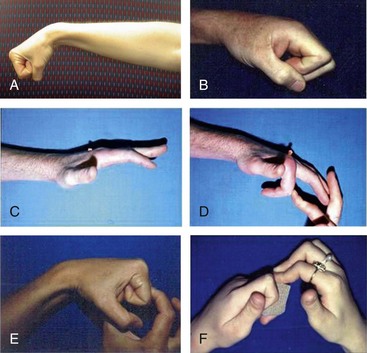

Figure 5A-8 Exercises for insufficient finger flexion caused by extensor tendon adhesions or shortness. A and B, Active composite finger flexion for shortness or adhesions. C, Active composite extension for adhesions to increase extensor tendon gliding proximally. D, Passive finger flexion for adhesions to increase extensor tendon gliding distally. E and F, Composite passive finger flexion for adhesions to increase extensor tendon gliding distally or lengthen short extensors.

(B to F, Used with permission from Ann Kammien, PT CHT, St Louis, Mo.)

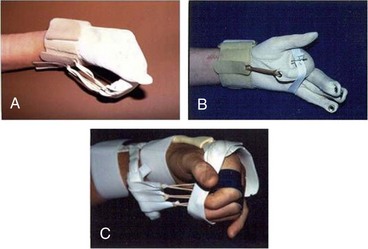

Figure 5A-10 Insufficient finger flexion caused by extensor tendon shortness or adhesions. A, Flexion glove for gentle composite stretch to fingers into flexion. B, Addition of elastic band around hand and middle phalanges to flexion glove to increase MP and PIP flexion. C, Dynamic MP and IP flexion splint.

(Used with permission from Ann Kammien, PT CHT, St Louis, Mo.)

See guidelines for progression of treatment in section on flexor tendon adhesions (see Box 5A-1).

Treatment for Insufficient Finger and/or Thumb Flexion Syndrome Caused by MP Collateral Ligament and/or IP Dorsal Capsule Shortness or Adhesion5,16

Treatment isolates motion to the joint that is stiff so that the joint that is relatively most flexible does not move. Often, decreasing the amount of effort is helpful to obtain precise movement at the involved joint.

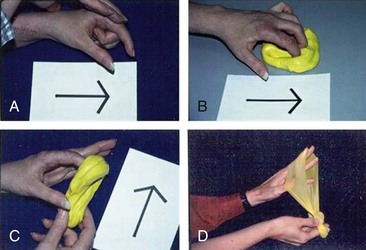

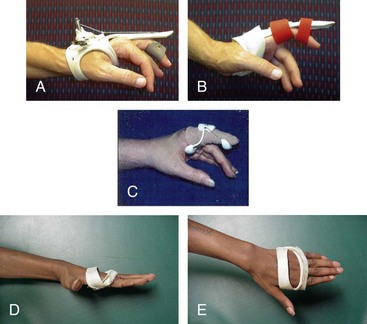

Figure 5A-11 Exercises for insufficient finger flexion caused by joint structures. A, Active braced or blocked PIP flexion. B, Active braced or blocked MP flexion. C, Active MP flexion with uninvolved IP joints immobilized in extension. D, Passive MP flexion with wrist stabilized.

(Used with permission from Ann Kammien, PT CHT, St Louis, Mo.)

Figure 5A-13 Insufficient finger flexion caused by shortness of PIP or DIP dorsal capsule. Elastic flexion splint to increase PIP and DIP flexion (best for DIP).

(Used with permission from Ann Kammien, PT CHT, St Louis, Mo.)

Figure 5A-14 Insufficient finger flexion caused by MP collateral ligament shortness or adhesions. A, Treatment initiated early while still casted by adding slings to pull MP joints into flexion. B, Dynamic MP flexion splint. C, Static progressive MP flexion splint.

(Used with permission from Ann Kammien, PT CHT, St Louis, Mo.)

Treatment for Insufficient Finger and/or Thumb Flexion Syndrome Caused by ORL Shortness24 (Figure 5A-15)

Treatment is simultaneous DIP flexion with PIP extension exercises performed actively, passively, or with resistance. In some cases, splinting to hold the PIP joint in extension may be helpful.

Treatment for Insufficient Finger and/or Thumb Flexion Syndrome Caused by Intrinsic Muscle Shortness16

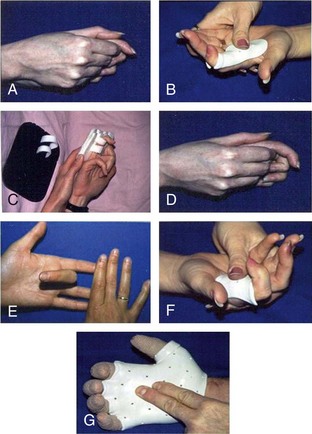

Figure 5A-16 Insufficient finger flexion caused by short intrinsic muscles. A, Passive IP flexion with MP in extension to stretch interossei. B, Active IP flexion with MP’s in extension. C, Index MP abduction with IPs flexed and MP in extension to stretch first palmar interossei. D, Resistive hook fist with resistive putty.

Treatment for Insufficient Finger and/or Thumb Flexion Syndrome Caused by Swan Neck Deformity

Treatment is controversial; some experts say no improvement occurs with conservative treatment or splinting. Others recommend splinting and exercises to correct joint contractures and intrinsic shortness in the early stages.27 Surgery is usually necessary for lasting correction.

Treatment for Insufficient Finger and/or Thumb Flexion Syndrome caused by Weakness of Flexors

Overload the muscle progressively as appropriate for the specific strength of the muscle. Exercises should be done every other day, 3 sets of 10 to 15 repetitions each time, once strength is greater than 3+/5. Exercises can be performed more often at the weaker grades. May need to use tenodesis action with the wrist to achieve finger flexion if no finger flexion available actively.

Treatment for Insufficient Finger and/or Thumb Flexion Syndrome Caused by Rupture of Flexor Tendon

Contact physician same day and schedule appointment for patient to see physician.

Insufficient Finger and/or Thumb Extension Syndrome

The principal impairment in insufficient finger and/or thumb syndrome is limited finger and/or thumb extension AROM, but the key to prescribing the appropriate intervention is differentiating between the sources causing the limited extension. The sources of the limited extension can be broadly classified into two main categories: hypomobility (physiological and accessory motion) or force production deficit (decreased strength). Insufficient finger and/or thumb extension syndrome is most commonly secondary to a trauma or injury or after a period of immobilization to allow for tissue healing. Initially, these patients may be assigned a movement system diagnosis of hand impairment Stage 1, but an underlying movement system diagnosis of insufficient finger and/or thumb extension syndrome may help guide treatment. As the tissues heal, the diagnosis may change from hand impairment to another movement system diagnosis such as insufficient finger and/or thumb extension syndrome. The “Source of Signs and Symptoms” column provides key information regarding the cluster of findings identifying the source of the limited extension. The identified source or cause of insufficient finger and/or thumb extension comprises the second part of the name of the syndrome.

Treatment for Insufficient Finger and Thumb Extension

See Box 5-2 for treatment of scar and edema. The therapist must avoid applying excessive force when performing passive stretching exercises on patients that have hand injuries. Overly aggressive exercise increases swelling and may result in increased fibrosis and limitation of ROM.

Treatment for Insufficient Finger and/or Thumb Extension Syndrome Caused by Flexor Tendon Adhesions/Shortness

Treatment of adhesions requires active and resistive contraction of flexors. Treatment of both adhesions and shortness require stretching into composite extension (see Box 5A-2).

Treatment for Insufficient Finger and/or Thumb Extension Syndrome Caused by Extensor Tendon Adhesion

Treatment for Insufficient Finger and/or Thumb Extension Syndrome Caused by MP, PIP, or DIP Volar Plate and Accessory Collateral Ligament Shortness or Adhesion5,16

Figure 5A-19 Insufficient finger extension caused by shortness of PIP volar plate and accessory collateral ligaments. A and B, Static progressive PIP extension splint to increase PIP extension. C, Dynamic PIP extension splint (DeRoyal LMB Spring Finger extension assist [DeRoyal Industries, Powell, Tenn.]) used during the day to increase PIP extension ROM. D and E, Anti-claw splint can be used as an aide to exercise, preventing MP extension while working to increase PIP extension.

Treatment for Insufficient Finger and/or Thumb Extension Syndrome Caused by Shortness of ORL24

Treatment is active, passive, or resistive exercises into simultaneous PIP extension with DIP flexion. In some cases, splinting to hold the PIP joint in extension may be helpful (see Figure 5A-15).

Treatment for Insufficient Finger and/or Thumb Extension Syndrome caused by Intrinsic Muscle Shortness16 (see Figure 5A-16)

Treatment for Weakness of ED

Treatment overloads the muscle progressively as appropriate for the specific strength of the muscle. Exercises should be done every other day, 3 sets of 10 to 15 repetitions each time, once strength is greater than 3+/5. Exercises can be performed more often at the weaker grades (Figure 5A-20).

Treatment for Insufficient Finger and/or Thumb Extension Syndrome Caused by Radial Nerve Injury with Paralysis of Finger and Thumb Extensors16,29

Treatment for Insufficient Finger and/or Thumb Extension Syndrome Caused by Severe Weakness of Intrinsic Muscles

Treatment for severe weakness of intrinsic muscles (“clawing” secondary to ulnar nerve injury)16,29 is as follows:

Conservative Treatment for Injury to Extensor Tendons

For conservative treatment for injuries to extensor tendons that do not require surgery, refer to established protocols.6,30

Insufficient Thumb Palmar Abduction and/or Opposition Syndrome

The principal impairment in insufficient thumb palmar abduction and/or opposition syndrome is limited thumb opposition and/or palmar abduction AROM, but the key to prescribing the appropriate intervention is differentiating between the sources causing the limited opposition/abduction. The sources of the limited thumb opposition/palmar abduction can be broadly classified into two main categories: hypomobility (physiological and accessory motion) or force production deficit (decreased strength). Insufficient thumb palmar abduction and/or opposition with hypomobility is most commonly secondary to a trauma or injury or after a period of immobilization to allow for tissue healing.16 Initially, these patients may be assigned a movement system diagnosis of hand impairment Stage 1, but another underlying movement system diagnosis of insufficient thumb opposition/palmar abduction may help guide treatment. As the tissues heal, the diagnosis may change from hand impairment to another movement system diagnosis. Insufficient thumb palmar abduction and/or opposition with hypomobility may also be secondary to paralysis after a median nerve injury.16 However, if there is any active function of the median nerve–innervated muscles, then force production deficit instead of hypomobility would guide treatment. A third reason for the insufficient thumb palmar abduction and/or opposition with hypomobility might be joint subluxation and deformity secondary to osteoarthritis of the CMC joint of the thumb.9,31 The “Source of Signs and Symptoms” column provides key information regarding the cluster of findings identifying the source of the insufficient thumb palmar abduction or opposition. The identified source or cause of insufficient finger and/or thumb extension comprises the second part of the name of the syndrome.

Force Production Deficit

Insufficient Thumb Opposition/Abduction Caused by Median Nerve Injury with Strength 2/5

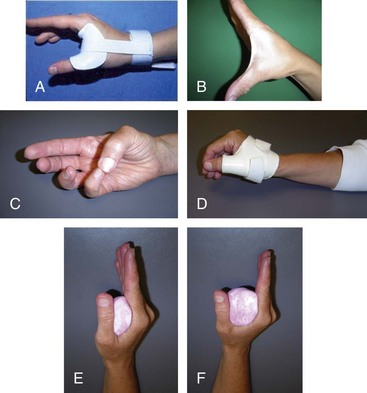

Figure 5A-21 Insufficient thumb opposition/abduction. A, Use of custom static splint for stretching of first web space or prevention of contracture. B, Palmar abduction exercising the abductor pollicis brevis. C, Exercise for the opponens pollicis. D, Opposition splint for functional use after median nerve injury. E and F, Use of Otoform K for progressive stretching of limited first web space.

Hypomobility

Insufficient Thumb Opposition/Abduction Caused by Median Nerve Injury with Strength 0/5 to 1/5

Insufficient Thumb Opposition/Abduction Caused by Contracture of Thumb Adductor Muscles, CMC Joint Structures, or Scar

Insufficient Thumb Opposition/Abduction Caused by CMC Subluxation/Deformity

Figure 5A-22 Splinting for insufficient thumb opposition/palmar abduction. A, Thermoplastic forearm-based static thumb splint immobilizing the wrist, CMC, and MP. B, Thermoplastic hand-based static thumb splint immobilizing the CMC and MP. C, Neoprene hand-based Comfort Cool static thumb splint immobilizing the CMC and MP. D, Hand-based static thumb splint immobilizing the CMC.

Stabilizing the MP joint in 30 degrees of flexion may unload the anterior compartment of the CMC joint, which is often involved.46

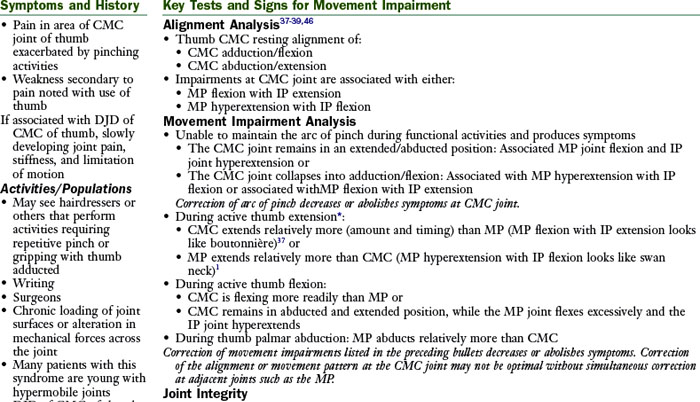

Thumb Carpometacarpal Accessory Hypermobility Syndrome

In the thumb CMC accessory hypermobility syndrome, pain is located at the CMC joint, but the alignment and movement impairments occur at all joints of the thumb. The CMC joint may be either extended/abducted or adducted/flexed. The impairments at the CMC joint are associated with either (1) MP flexion with IP extension or (2) MP extension with IP flexion and result in loss of the normal longitudinal arch of the thumb. This movement pattern is due to an inability to coordinate the timing and sequencing of the movements between the IP, MP, and CMC joints of the thumb and adaptive changes in the tissues. Correction of the impairments decreases the symptoms. The adductor pollicis and FPB are frequently overused relative to the APL, APB, OP, EPB, and FPL. Patients assigned to this diagnosis must have a modifiable movement pattern. This diagnosis is not intended for patients with neurological injury or those in the later stages of arthritis.

Treatment for Thumb CMC Accessory Hypermobility

Patient Education

Exercises

Exercises are recommended, especially for Stages I and II in which the joint is not already subluxed. The focus of the exercises is increasing the performance (timing) of the underused muscle. In doing so, the extensibility of the antagonistic muscle is simultaneously increased (stretched). The exercises are used to correct the movement patterns, thus balancing the mechanical forces to which the joint is subjected.40

Recommendations have been made to begin isometric and then progressive resistive exercises for palmar abduction after the acute symptoms have subsided. The goal is to help to stabilize the thumb CMC joint subluxation.51

Strengthening of the APL helps maintain stability of the thumb CMC joint: Work on active contraction in the correct alignment. The APL helps to maintain stability of the joint if the joint is aligned well. The APB places the thumb in the position of maximal stability of the thumb CMC joint.50-52 The angle of pull of the first dorsal interosseous muscle is such that it would stabilize the base of the first metacarpal from dorsoradial subluxation.18

Exercises to correct arc of thumb are as follows (for figures refer to main text of chapter):

Once patient is able to correct the movement pattern without added resistance, progress by exercising the muscles noted here with resistive putty or rubber bands. Increase extensibility of stiff muscles by instructing the patient to take frequent breaks to stretch throughout the day and especially during the functional activity that is contributing to the impairment.

Purpose of Splinting16,28,40

Splint/taping assists maintaining the arc of the thumb. The first priority is usually to correct the movement impairment with patient education and exercises, but splinting may be a helpful adjunct. The main purpose of a splint is to decrease pain by stabilizing the CMC joint in the correct alignment. The CMC joint is most stable in a position of abduction and opposition. Correcting MP alignment can facilitate correct CMC alignment. Splinting is most effective for patients with Eaton’s Stage I or II CMC arthritis. Although thermoplastic splints provide stability to the CMC, the hard plastic in the palm of the hand inhibits function so compromises in the type of splint prescribed, often have to be made to ensure patient compliance with splint use. Additional purposes of splinting are as follows:

Joint Protection/Adaptive Equipment

Joint protection/adaptive equipment can facilitate the correct alignment and movement pattern40 as follows:

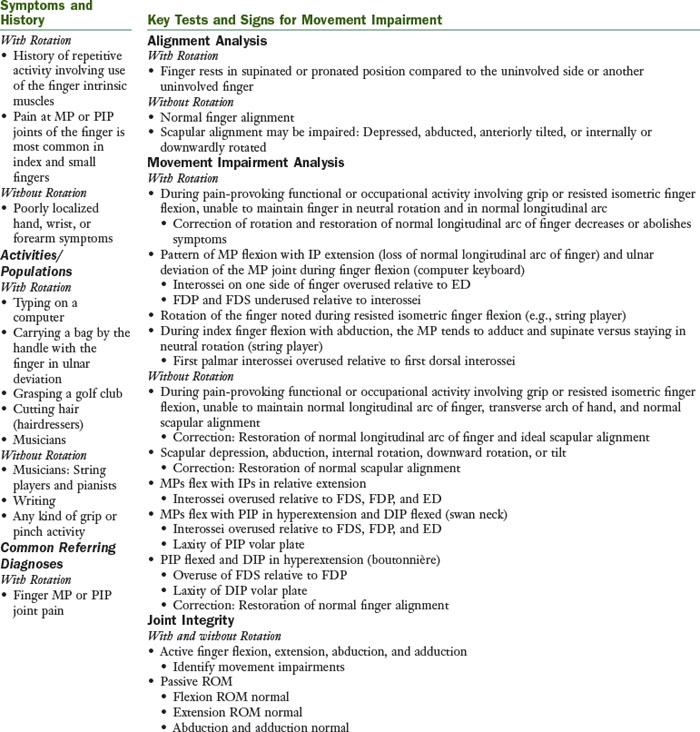

Finger (or Thumb) Flexion Syndrome with or without Finger Rotation

The principal movement impairment of finger (or thumb) flexion syndrome is the inability to maintain the normal alignment of the finger during finger flexion. This includes one or more of the following: the longitudinal arch, neutral rotation, or neutral abduction/adduction of the finger. The movement impairment occurs during the pain-provoking functional or occupational activity involving grip or resisted isometric finger flexion. The movement pattern may be due to an inability to coordinate the timing and sequencing of the movements, an alteration of the relative amount of motion between the IP and MP joints of the finger, or overuse during a repetitive activity. Finger MP or PIP joint pain associated with rotation is due to insufficient performance of one interossei muscle and overuse of the antagonistic interossei muscle at the same joint.53 The overused muscle is relatively stiffer than its antagonist. This results in the principal impairment of rotation at the painful joint and results from a repetitive activity. Finger AROM and strength are usually normal. Correction of the movement impairments does not always modify symptoms immediately but instead over time. Patients assigned this diagnosis must have a modifiable movement pattern. This diagnosis is not intended for patients with neurological injury or later stages of arthritis. This syndrome can be associated with a scapular movement impairment but the symptoms are not referred from shoulder or neck structures. Restoration of normal scapular alignment is believed to provide proximal stability, allowing distal segments to work optimally by decreasing excessive stresses on distal tissues.

Treatment for Finger (or Thumb) Flexion Syndrome with Rotation

Exercises

Stretch or increase the extensibility of the short or stiff interossei—if the first palmar interosseous muscle is short or relatively stiff, abduct the index MP with the MP in extension and the IP joints flexed (Figure 5A-16, C).

Work the long or relatively less stiff interossei muscles (e.g., if the first palmar interosseous is short, the first dorsal interosseous muscle may need to be stiffer or strengthened). Working the first DI by abducting the index finger actively while maintaining the MP joint extended and the IP joints flexed would accomplish stretching the first palmar interosseous while strengthening the first DI.

Treatment for Finger (or Thumb) Flexion Syndrome without Rotation

Patient Education

Maintain arc of finger during resisted isometric finger flexion activities while maintaining proper scapular alignment and movement. Work with patient on correcting and practicing the movement pattern during the functional activity that is causing the problem.

Exercises

Increase extensibility of stiff muscles by taking frequent breaks to stretch throughout the day and especially during the functional activity that is contributing to the impairment.

Splint/taping may be helpful to assist maintaining the arc of the finger. The first priority is usually to correct the movement impairment with patient education and exercises, but splinting may be a helpful adjunct.

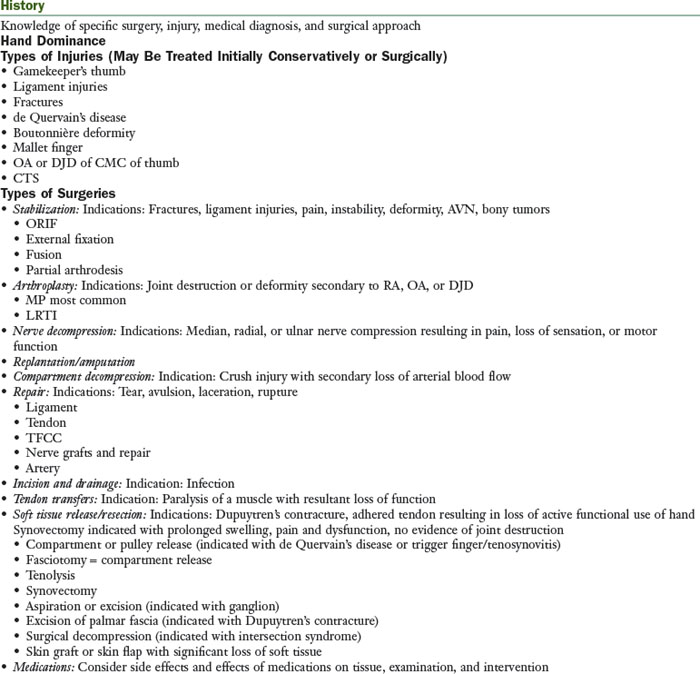

Source or Regional Impairment of the Hand

The movement system diagnosis “hand impairment” is used when the pathoanatomical source diagnosis is not provided on the referral documentation. The focus of the treatment is protecting the injured tissues. Usually, there is a history of acute trauma or injury to the hand or the patient is in the early in postoperative phase. Medical precautions have been issued, thus the patient’s typical movement pattern cannot be assessed at this time. Prognosis is for tissue healing, and normal movement is expected. The determination of the use of component versus compensatory treatment methods depends on the expectations of the final outcome. Initially, while on precautions, compensatory methods may be necessary. The information for the regional impairment of the hand diagnosis in this appendix is intended only as a general guide; therefore the physician’s protocol for specific precautions and progression must be consulted. The therapist must be familiar with the tissues that are affected by the surgical procedure and the specific surgical approach.

Moderators

Age, quality of tissue at repair site and tension on repair, extent of injury (degree of soft tissue involvement), location of injury, duration of immobilization, and surgical approach are moderators that should be considered. The patient may have an increased healing time with osteoporosis, a history of diabetes, or steroid use.

Impairments (Body Functions and Structures)

Pain

Stage 1 (surgical or acute injury): Within the first 2 weeks of the postoperative period, some pain will be associated with the exercises. (In contrast to the nonsurgical patient, in whom pain should not be reproduced with exercise.) Gradually, over the next few weeks, pain associated with the exercise should lessen. Pain should not be severe and should not be increased for more than 1 hour after exercise. Exercise can also help decrease complaints of stiffness. Severe pain can indicate being too aggressive with exercises. After a tenolysis, the patient must be able to work through pain to maintain the tendon glide.22 Complaints of increasing pain, pain that is not decreasing with treatment, or burning pain are all “red flag” indicators that treatment is too aggressive or there is a disruption in the usual course of healing (e.g., CRPS/RSD, nonunion of fracture, and so on). Coordinating the use of analgesics with exercise sessions is important. Splinting may be used during this period to protect the injured tissue.

Stages 2 to 3: Pain associated with the specific tissue that was involved in the surgery should be significantly decreased by weeks 4 to 6. Precautions may be lifted during or by postoperative weeks 4 to 6. As the exercises and activities of the patient are progressed, pain should be monitored closely. Although the patient may still have some increased pain with activity, the patient should report a decrease in pain overall, despite the increase in activity.

Edema

Stage 1 (surgical or acute injury): Early management of edema is the key to a successful outcome of therapy for a postoperative hand patient. The hand must be elevated above the level of the heart as much as possible. AROM, splinting to immobilize and rest the tissue, compressive garments or wraps, milking massage, and/or ice or other modalities may help decrease the edema. Caution must be used in donning a compressive garment when precautions regarding motion are present. An increase in edema or edema that is not decreasing with treatment are indications that exercises are too aggressive. This could also be an indicator of an infection. If infection is suspected, the physician should be contacted immediately.

Stages 2 to 3: Edema should decrease significantly in the first 2 to 4 weeks after surgery. Some edema, however, may persist for several months. As activities and exercises are progressed, the edema should continue to decrease gradually.

Appearance

Stage 1 (surgical or acute injury): Infection should be suspected if the area around the incision or the involved joint appears to be red, hot, and swollen.58 The physician should be consulted immediately if infection is suspected. The incision will have stitches for the first 7 to 14 days. The patient may also have pins that protrude from the finger. Bruising is not uncommon postoperatively. Changes in hair growth, perspiration, or color may indicate some disturbance to the sympathetic nervous function, especially in combination with the complaint of excessive pain.59 However, dark hair growth on the arm after casting is very common. Stages 2 to 3: The incision should be well healed. Bruising should be diminishing. Signs of increased bruising are a red flag and the patient should be immediately referred to the physician.

Scar

Stage 1 (surgical linear scars): Scarring, although a normal process of healing, must be managed well in the hand or it can severely limit function. Gliding between adjacent structures in the hand must occur to allow good motion and function. Early management of scar contributes to a good outcome. Exercise, massage, compression, silicone gel sheets, and vibration are used in the management of scar. The use of silicone gel is best supported by evidence in the literature. However, clinical experts also commonly use the other methods of scar management. Further research is needed to determine the efficacy of these other methods. The gradual application of stress to the scar or incision helps the scar remodel so that it allows the necessary gliding between structures. A dry incision that has been closed and reopens as a result of the stresses applied with scar massage indicates that the scar massage is too aggressive. Scars may be classified according to type. Linear scars that are immature are confined to the area of the incision. They may be raised and pink or reddish in the remodeling phase. As they mature, they become whitish and flatten. A hypersensitive scar requires desensitization. See Box 5-2 for treatment guidelines on managing scar.

Stages 2 to 3: A scar may continue to remodel for up to 2 years.19 Scar management techniques may be effective until the scar matures, although they are probably most effective early in the healing process.

Range of Motion

Stages 2 to 3: Precautions regarding ROM will usually be lifted sometime in the first 6 weeks after surgery or injury so there are no precautions by this stage. Once precautions have been lifted, if there is a plateau in the improvement of ROM with the use of active exercise, exercises are progressed to passive. If ROM is still not improving by at least 10 degrees per week, then static progressive or dynamic splinting should be initiated. Increasing ROM may still be the primary focus of treatment, although strengthening can begin through increased functional use.

Strength

Stage 1: Generally, strengthening is not done during the first 4 to 6 weeks after an injury or surgery. During Stage 1, focus instead is either on immobilization, decreasing edema, scar management, or on gaining ROM, with the correct movement pattern. Occasionally, light resistance is used to increase the recruitment of a muscle versus overload and strengthening. If this is done, it should not violate any precautions that are still in force.

Stages 2 to 3: It is generally safe to begin strengthening exercises 6 weeks after a surgery or fracture. The specific protocol or the physician should be consulted for the exact time when strengthening can be initiated. Once the physician has lifted any precautions related to strengthening, progression to resistive exercise is based on the patient’s ability to perform AROM with a good movement pattern and without a significant increase in pain relative to the pain produced with the same movement without resistance. Refer to specific protocols for guidelines regarding progression to resistance. Vital signs should be monitored when initiating an upper extremity resistive exercise program, particularly at higher levels such as using the BTE.

Coordination

Stage 1: Exercises focusing on coordination are generally not initiated until later in the rehabilitation phase.

Stages 2 to 3: Often, specific exercises for coordination are not necessary. The patient will regain their coordination through increasing the functional use of their hand, as well as through the exercises prescribed for regaining ROM and strength. However, in certain instances, specific exercises for coordination may be useful. One example of this would be a patient who is learning to use his or her nondominant hand as his or her dominant hand. This patient may require specific writing exercises.

Cardiovascular and Muscular Endurance

Stage 1: Patients may become deconditioned after a severe hand injury. Resuming or initiating an exercise program, such as walking, to increase cardiovascular endurance is indicated as soon as pain allows, assuming the exercise does not violate any precautions related to the tissue healing.

Stages 2 to 3: The intensity, duration, and frequency of the exercise can be progressed as tolerated. Cardiovascular endurance exercises may have an added benefit of helping decrease pain and generally increase the patient’s feeling of well-being.

Patient Education

Stages 1 to 3: The patient will need to be educated regarding the specific medical precautions, how to maintain precautions during hygiene, and the definition of PROM or assisted AROM. Educate the patient regarding the structures and tissues involved. Use of a hand model, anatomical pictures, handouts, and books are helpful. Also, the patient must be educated regarding the care, use, precautions, schedule for use, and how to don and doff his or her splints.

Changes in Status

Stages 1 to 3: Consider reports of increased pain or edema, decreased strength, or significant change in ROM carefully, especially in combination. The patient should be questioned regarding precipitating events (e.g., time of onset, activity, and so on). If the integrity of the surgery is in doubt, contact the physician promptly. If patient has fever and erythema spreading from the incision, the physician should be contacted because of the possibility of an infection.

Function (Activity Limitations/Participation Restrictions)

General Guidelines

Stage 1: Early functional use of the hand must be encouraged while protecting the healing tissue. Educate the patient regarding precautions/restrictions and use of the involved extremity during ADLs such as eating, bathing, dressing, work, and so on). Educate patient regarding the use of splint as needed.

Stages 2 to 3: Once any precautions have been lifted, the patient may need to be instructed to specifically return to using the hand functionally since he or she may avoid using the hand because of habit.

Specific Suggestions

Medications/Modalities

Medications

During the immediate postoperative phase, physical therapy treatment should be timed with analgesics. This is particularly important in the first 2 weeks after tenolysis, so the patient is able to work through pain to maintain the ROM gains achieved during the surgery. Communication with the physician is vital to provide optimal pain relief for the patient.

Whirlpool Treatment25

In general, use of whirlpools for treatment of patients with hand injuries is contraindicated because both the dependent position of the hand in the whirlpool and the warm water temperature encourage increased edema in the hand. If a whirlpool must be used, the water temperature should be no warmer than 98° F.

Paraffin or Hot Pack Treatment25

The patient’s hand should be elevated while receiving either of these heat modalities to prevent an increase of edema. Paraffin can be used with the hand wrapped in a flexed position with Coban to increase the extensibility of the structures limiting finger flexion.

Electrical Stimulation25

Electrical stimulation is used by some clinical hand experts to increase tendon gliding and increase strength.

Tissue Factors

1 Knight SL. Assessment and management of swan neck deformity. Int Congr Ser. 2006;1295:154-157.

2 Aulicino PL. Clinical examination of the hand. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

3 Culp RW, Taras JS. Primary care of flexor tendon injuries. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

4 Stewart Pettengill KM, van Strien G. Postoperative management of flexor tendon injuries. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

5 Innis PC. Surgical management of the stiff hand. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

6 Rosenthal EA. The extensor tendons: anatomy and management. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

7 Cambridge-Keeling CA. Range-of-motion measurement of the hand. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

8 Tubiana R, Thomine J, Mackin E. Examination of the hand and wrist, ed 2. London: Informa Healthcare; 1996.

9 Neumann DA. Kinesiology of the musculoskeletal system: foundations for physical rehabilitation. St Louis: Mosby; 2002.

10 Littler JW, Eaton RG. Redistribution of forces in the correction of boutonnière deformity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1967;49(7):1267-1274.

11 Matev I. The boutonnière deformity. Hand. 1969;11(2):90-95.

12 Stanley J. Boutonnière deformity. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(Supp III):216a.

13 Kendall FP, McCreary EK, Provence PG, et al. Muscles: testing and function with posture and pain, ed 5. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

14 Campbell PJ, Wilson RL. Management of joint injuries and intraarticular fractures. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

15 Alter S, Feldon P, Terrono AL. Pathomechanics of deformities in the arthritic hand and wrist. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

16 Colditz JC. Anatomic considerations for splinting the thumb. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

17 Villeco JP, Mackin EJ, Hunter JM. Edema: therapist’s management. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

18 Brand PW, Hollister AM. Clinical mechanics of the hand, ed 3. St Louis: Mosby; 1999.

19 Mustoe TA, Cooter RD, Gold MH, et al. International clinical recommendations on scar management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;1102:560-571.

20 Magee DJ. Orthopedic physical assessment, ed 3. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1997.

21 Goodman CC, Snyder TEK. Differential diagnosis for physical therapists: screening for referral, ed 4. St Louis: Saunders; 2007.

22 Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors. Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

23 Fess EE. Documentation: essential elements of an upper extremity assessment battery. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

24 Evans RB. Clinical management of extensor tendon injuries. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

25 Michlovitz SL. Ultrasound and selected physical agent modalities in upper extremity rehabilitation. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman EL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

26 LaStayo PC. Ulnar wrist pain and impairment: a therapist’s algorithmic approach to the triangular fibrocartilage complex. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

27 Sandoval R, Kare JA, Washington IE, et al. Swan neck deformity. Available at http://www.emedicine.com/orthoped/topic562.htm Accessed June 29, 2010.

28 Biese J. Therapist’s evaluation and conservative management of rheumatoid arthritis in the hand and wrist. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

29 Skirven TM, Callahan AD. Therapist’s management of peripheral nerve injuries. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

30 Cannon NM, Beal BG, Walters KJ, et al. Diagnosis and treatment manual for physicians and therapists: upper extremity rehabilitation, ed 4. Indianapolis: The Hand Rehabilitation Center of Indiana; 2001.

31 Eaton RG, Glickel SZ. Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. Staging as a rationale for treatment. Hand Clin. 1987;3(4):455-471.

32 Wajon A, Ada L, Edmunds I: Surgery for thumb (trapeziometacarpal joint) osteoarthritis, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD004631, 2005.

33 Swanson AB. Disabling arthritis at the base of the thumb: treatment by resection of the trapezium and flexible (silicone) implant arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(3):456-471.

34 Tomaino MM, Pellegrini VDJr, Burton RI. Arthroplasty of the basal joint of the thumb. Long-term follow-up after ligament reconstruction with tendon interposition. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(3):346-355.

35 Eaton CJ, Lister GD. Radial nerve compression. Hand Clin. 1992;8(2):345-357.

36 Kovler M, Lundon K, McKee N, et al. The human first carpometacarpal joint: osteoarthritic degeneration and 3-dimensional modeling. J Hand Ther. 2004;17(4):393-400.

37 Nalebuff EA. Diagnosis, classification and management of rheumatoid thumb deformities. Bull Hosp Joint Dis. 1968;29(2):119-137.

38 Terrono AL. The rheumatoid thumb. J Am Soc Surg Hand. 2001;1(2):81-92.

39 Tomaino MM. Classification and treatment of the rheumatoid thumb. Int Congr Ser. 2006;1295:162-168.

40 Melvin JL. Therapists’ management of osteoarthritis in the hand. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

41 Hayes EP, Carney K, Wolf JM, et al. Carpal tunnel syndrome. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

42 Terrono AL, Nalebuff EA, Philips CA. The rheumatoid thumb. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

43 Weiss S, LaStayo P, Mills A, Bramlet D. Splinting the degenerative basal joint: custom-made or prefabricated neoprene? J Hand Ther. 2004;17(4):401-406.

44 Wajon A. Clinical splinting successes: the thumb “strap splint” for dynamic instability of the trapeziometacarpal joint. J Hand Ther. 2000;13(3):236-237.

45 Galindo A, Lim S. A metacarpophalangeal joint stabilization splint: the Galindo-Lim thumb metacarpophalangeal joint stabilization splint. J Hand Ther. 2002;15(1):83-84.

46 Moulton MJ, Parentis MA, Kelly MJ, et al. Influence of metacarpophalangeal joint position on basal joint-loading in the thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(5):709-716.

47 Colditz JC. The biomechanics of a thumb carpometacarpal immobilization splint: design and fitting. J Hand Ther. 2000;13(3):228-235.

48 Pellegrini VDJr. Pathomechanics of the thumb trapeziometacarpal joint. Hand Clin. 2001;17(2):175-184.

49 Cyriax J. Textbook of orthopaedic medicine, ed 7. London: Bailliere Tindall; 1978.

50 Poole JU, Pellegrini VDJr. Arthritis of the thumb basal joint complex. J Hand Ther. 2000;13(2):91-107.

51 Pellegrini VDJr. Osteoarthritis at the base of the thumb. Orthop Clin North Am. 1992;23(1):83-102.

52 Neumann DA, Bielefeld T. The carpometacarpal joint of the thumb: stability, deformity, and therapeutic intervention. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33(7):386-399.

53 Schreuders TAR, Brandsma JW, Stam HJ. The intrinsic muscles of the hand: function, assessment and principles for therapeutic intervention. Phys Med Rehab Kuror. 2007;17:20-27.

54 Landsmeer JM. The anatomy of the dorsal aponeurosis of the human finger and its functional significance. Anat Rec. 1949;104(1):31-44.

55 Shrewsbury MM, Johnson RK. A systematic study of the oblique retinacular ligament of the human finger: its structure and function. J Hand Surg Am. 1977;2(3):194-199.

56 Dell PC, Sforzo CR. Ulnar intrinsic anatomy and dysfunction. J Hand Ther. 2005;18(2):198-207.

57 Sahrmann SA. Diagnosis and treatment of movement impairment syndromes. St Louis: Mosby; 2002.

58 Nathan R, Taras JS. Common infections in the hand. In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

59 Koman LA, Smith BP, Smith TL. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy (complex regional pain syndromes: types 1 and 2). In Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

60 Butler DS. Mobilisation of the nervous system. Melbourne: Churchill Livingstone; 1994.

61 Mackin EJ, Callahan A, Osterman AL, editors. Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.