Mobility

Section 1: Functional Ambulation

Section 2: Wheelchair Assessment and Transfers

Wheelchair ordering considerations

Manual vs. electric/power wheelchairs

Manual recline vs. power recline vs. tilt wheelchairs

Folding vs. rigid manual wheelchairs

Lightweight (folding or nonfolding) vs. standard-weight (folding) wheelchairs

Standard available features vs. custom, top-of-the-line models

Wheelchair measurement procedures

Additional seating and positioning considerations

Preparing the justification/prescription

Guidelines for using proper mechanics

Principles of body positioning

Bent pivot transfer: bed to wheelchair

Transfers to household surfaces

Section 3: Transportation, Community Mobility, and Driving Assessment

The role of occupational therapy

Supplemental transportation programs for seniors

Occupational therapists and driving

Occupational therapy assistants

Driving evaluations and disabilities

Cognitive and visual-perceptual skills

Driver recommendations and interventions

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

1 Define functional ambulation.

2 Discuss the roles of physical and occupational therapists and other caregivers in functional ambulation.

3 Identify safety issues in functional ambulation.

4 Recognize basic lower extremity orthotics and ambulation aids.

5 Develop goals and plans that can help ambulatory clients resume occupational roles.

6 Identify the components necessary to perform a wheelchair evaluation.

7 Explain the process of wheelchair measurement and prescription completion.

8 Identify wheelchair safety considerations.

9 Follow guidelines for proper body mechanics.

10 Apply principles of proper body positioning.

11 Identify the steps necessary for performing various transfer techniques.

12 Identify considerations necessary to determine the appropriate transfer method based on the client’s clinical presentation.

13 Identify different transportation systems and contexts and the treatment implications each system presents.

14 Discuss the multilevel role of the therapist in the occupation of community mobility.

15 List performance skills and client factors that should be assessed in a comprehensive driver evaluation.

16 Discuss the value of driving within this society and how loss of license or mobility affects participation in occupation.

17 Develop awareness of the complexities involved in a driver referral and evaluation.

18 Define primary and secondary controls.

19 Discuss that driver competency assessment is a specialty practice area requiring advanced training.

Walking, climbing stairs, traveling within one’s neighborhood, and driving a car are so universal and customary that most people would not consider these to be complex activities. The basic capacities to move within the environment, to reach objects of interest, to explore one’s surroundings, and to come and go at will appear natural and easy. For persons with disabilities, however, mobility is rarely taken for granted or thought of as automatic. A disability may prevent a person from using the legs to walk or using the hands to operate controls of motor vehicles. Cardiopulmonary and medical conditions may limit aerobic capacity or endurance, requiring the person to take frequent rests and to curtail walking to cover only the most basic of needs, such as toileting. Deficits in motor coordination, flexibility, and strength may seriously compromise movement and may make difficult any activities that require a combination of mobility (e.g., walking or moving in the environment) and stability (e.g., holding the hands steady when carrying a cup of coffee or a watering can).

Occupational therapy (OT) practitioners assist persons with mobility restrictions to achieve maximum access to environments and objects of interest to them. Typically, OT practitioners provide remediation and compensatory training. In so doing, therapists must analyze the activities most valued and the environments most often used by their clients and must consider any future changes that can be predicted from an individual’s medical history, prognosis, and developmental status.

This chapter guides the practitioner in evaluation and intervention for persons with mobility restrictions. Three main topics are explored. The first section addresses functional ambulation, which combines the act of walking within one’s immediate environment (e.g., home, workplace) with other activities chosen by the individual. Feeding pets, preparing a meal and carrying it to a table, and doing simple housework are tasks that may involve functional ambulation. Functional ambulation may be conducted with aids such as walkers, canes, or crutches.

The second section concerns wheelchairs and their selection, measurement, fitting, and use. For many persons with disabilities, mobility becomes possible only with a wheelchair and specific positioning devices. Consequently, individual evaluation is needed to select and fit this essential piece of personal medical equipment. Proper training in ergonomic use allows the person who is dependent on the use of a wheelchair many years of safe and comfortable mobility. Safe and efficient transfer techniques based on the individual’s clinical status are introduced in this chapter. Attention also is given to the body mechanics required to safely assist an individual.

The third section covers community mobility, which for many in the United States is synonymous with driving. Increased advocacy by and for persons with disabilities has improved access and has yielded an increasing range of options for adapting motor vehicles to meet individual needs. Public transportation also has become increasingly accessible. Driving is a complex activity that requires multiple cognitive and perceptual skills. Evaluation of individuals with medical conditions and physical limitations is thus important for the safety of the disabled person and the public at large.

Mobility is an area of OT practice that requires close coordination with other health care providers, particularly physical therapists (PTs) and providers of durable medical equipment. Improving and maintaining the functional and community mobility of persons with disabilities can be one of the most gratifying practice areas. Clients experience tremendous energy and empowerment when they are able to access and explore wider and more interesting environments.

Section 1 Functional Ambulation

Occupational therapists (OTs) work with many types of clients who may have impaired ambulation because of disease or trauma. These impairments may be temporary or long term. For example, an elderly person with a hip fracture may require the use of a walker for several weeks or months until the bone is healed and strength is regained. Persons with a spinal cord injury may have permanent motor and sensory losses that require lower extremity bracing and the use of crutches for walking. They may be ambulatory only part of the time and may use a wheelchair part of the time. This depends on several factors, including the level of injury, the amount of energy required for ambulation, and their occupational roles.

Functional ambulation, a component of functional mobility, is the term used to describe how a person walks while achieving a goal, such as carrying a plate to the table or carrying groceries from the car to the house. Functional ambulation training is applicable for all individuals with safety or functional impairments and for a variety of diagnoses, such as lower extremity amputation, cerebrovascular accident, brain trauma or tumor, neurologic disease, spinal cord injury, orthopedic injury, and total hip or knee replacement.

Ambulation evaluation, gait training (treatments used to improve walking and ameliorate deviations from normal gait), and recommendations for bracing and ambulation aids are included in the professional role of the PT. The PT makes recommendations that can be followed by the client, families, hospital staff, or other caregivers. The OT works closely with colleagues in physical therapy to determine when clients may be ready to advance to the next levels of functional performance. For example, the OT may begin to have a client walk to the bathroom for toileting instead of using a bedside commode when the PT reports that the client is safe to walk the distance from the bed to the bathroom. The PT may recommend certain techniques or cueing to improve safety. Mutual respect and good communication between all team members help in coordination of care for clients. For example, a client with Parkinson’s disease may walk well with the PT immediately after taking his medication in the morning, but may have difficulty preparing lunch a few hours later, when the effects of medication are waning.

The following section is meant to provide an introduction to the OT about the basics of ambulation and aids such as crutches, canes, walkers, and braces to assist with teaching of activities of daily living (ADLs). It is not meant as a substitute for close collaboration with a PT.

Basics of Ambulation

Normal walking is a method of using two legs, alternately, to provide support and propulsion. Gait and walking are often used interchangeably, but gait more accurately describes the style of walking. The “normal” pattern of walking includes components of body support on each leg alternately (stance phase), advancement of the swinging leg to allow it to take over a supporting role (swing phase), balance, and power to move the legs and trunk. Normal walking is achieved without difficulty and with minimal energy consumption.

Descriptors of the events of walking include loading response, midstance, terminal stance and pre-swing, and midswing and terminal swing, with the duration of the complete cycle called cycle time. Cadence is the average step rate. Stride length is the distance between two placements of the same foot. It may be shortened in people with a variety of diseases. Walking base is the distance between the line of the two feet. It may be wider than normal for people with balance deficits.162

Abnormal gait is caused by disorders of the complex interaction between neuromuscular and structural elements of the body. It may result from problems with the brain, spinal cord, nerves, muscles, joints, or skeleton, or from pain. Problems may include weakness, paralysis, ataxia, spasticity, loss of sensation, and inability to bear weight through the limb or pelvis. Deficits may include decreased velocity, decreased weight bearing, increased swing time of the affected leg, an abnormal base of support, and balance problems. Functional deficits may include loss of mobility, decreased safety (increased fall risk), and insufficient endurance. The OT should reinforce gait training by following the recommendations of the PT.

Orthotics

As the PT evaluates the causes of gait problems, orthotics and ambulatory aids may be recommended. The OT should be familiar with basic lower extremity (LE) orthotics, including the reason for bracing. The OT may teach clients to put on the orthotics as part of dressing training.

Orthotics, or braces, are used to provide support and stability for a joint, to prevent deformity, or to replace lost function. They should be comfortable, easy to apply, and lightweight, if possible. The more joints of the lower extremity require bracing, the higher is the energy cost of ambulation.

Orthotics are named by the part of the body that is supported. A supramalleolar orthosis (SMO, or SMAFO) is made of plastic and fits into a shoe. It provides medial-lateral stability at the ankle, provides rear foot alignment during gait, supports midfoot laxity, and can control pronation/supination positions of the forefoot. It is not useful in cases of high tone or limited dorsiflexion. An ankle-foot orthosis (AFO) is usually made of plastic; it inserts into a shoe and extends up the back of the lower leg. It is sometimes called a foot drop splint, because it is used in cases of central or peripheral nerve lesions, which cause weakness of ankle dorsiflexors. An AFO may consist of one piece or may be hinged to permit ankle dorsiflexion. A knee-ankle-foot orthosis (KAFO) may be recommended for clients with knee weakness or hyperextension, or with foot problems. The KAFO might be used with diagnoses such as paraplegia, cerebral palsy, or spina bifida. For clients with spinal cord lesions or spina bifida involving the hip muscles, a hip-knee-ankle-foot orthosis (HKAFO) might be used. A reciprocating gait orthosis (RGO) is a type of HKAFO that may be used to help advance the hip in the presence of hip flexor weakness. High energy costs are associated with use of HKAFOs, and clients’ upper extremities are used for support on walkers and crutches. This makes functional ambulation tasks extremely challenging for these clients, and it may be more energy efficient and safer to perform some tasks while seated in a chair or wheelchair.

Walking Aids

Ambulation aids may be used to compensate for deficits in balance and strength, to decrease pain, and to decrease weight bearing on involved joints and help with fracture healing, or in the absence of a lower extremity. Walking aids are generally classified as canes, crutches, and walkers. All three help support part of the body weight through the arm or arms during gait. They may also be sensory cues for balance and may enhance stability by increasing the size of the base of support.

A single-point cane may be used with clients who have minor balance problems, by widening the base of support or providing sensory feedback through the upper extremity about position. For clients with a painful hip or knee, a cane is most commonly used on the contralateral side to reduce loading on the painful joint. The cane is advanced during the swing phase of the leg it is protecting. Variations of cane designs include quad canes and hemi-walkers that are heavier and bulkier than single-point canes but provide greater stability.

Crutches are able to transmit forces in a horizontal plane because two points of attachment exist—one at the hand and the other higher on the arm. Clients should be cautioned not to lean on crutches at the axilla because this may cause damage to blood vessels or nerves. The lever between the axilla and the hand is long, and enough horizontal force can be generated to permit walking when one leg has restricted weight-bearing capacity, or when both legs are straight and have limited or no weight-bearing capacity. Crutches are suitable for short-term use, such as for a fractured leg.

Forearm crutches may also be called Lofstrand or Canadian crutches. The points of contact are on the hand and forearm. The lever arm is shorter than with axillary crutches, and they are lighter. Mobility is easier for most people using Lofstrand or forearm crutches than when using axillary crutches, and they are useful for active people with severe leg weakness. All crutches require good upper body strength.

Walkers are more stable than canes or crutches. With a “pick-up” style walker, the walker is moved first; the client takes a short step with each foot and then moves the walker again. This type of walking can be slow. Most clients who need a walker are able to use a “front-wheeled walker,” which has two wheels on the front, making it lighter and easier to advance. Another variation is to have four wheels, along with a braking system. Some walkers have seats so that clients can rest when they become fatigued. Walkers require the use of both arms but do not require as much upper body strength or balance as crutches. Forearm platforms can be added to forearm crutches or walkers when clients are unable to bear weight through their hands or wrists, perhaps because of fracture or arthritis. For example, Pyia is currently using a walker that supplies substantial support during ambulation but requires additional energy to use compared with a cane. The PT may recommend a cane as Pyia progresses, but a walker may still be necessary in some situations within the home environment.

Ambulation Techniques: Basic ambulation techniques recommended by the PT vary from client to client, depending on the individual’s goals, strengths, and weaknesses and may be more complex than the descriptions provided previously. The OT reinforces the PT’s recommendations and incorporates them into functional ambulation activities.

During functional ambulation on a level surface, the OT is positioned slightly behind and to one side of the client. The therapist may be on the client’s stronger or weaker side, based on the recommendations and preference of the PT or the goals of the activity. The therapist moves in tandem with the client when providing support during ambulation. The therapist’s outermost lower extremity moves with the ambulation aid, and the therapist’s inside foot moves forward with the client’s lower extremity. Of course, some clients may be independent with basic ambulation and may need guarding or assistance only when practicing new activities, such as transporting hot foods, mopping a floor, or reaching into a dryer.

Safety is the number one priority for clients during functional ambulation. Before beginning an evaluation of ADLs, the OT should know basic client information. The therapist reviews the medical record, especially the current status and precautions. Does the client use oxygen? Does it need to be increased during activity? In the hospital setting, it may be useful to be aware of hematocrit level, if available, to help predict how much activity the client may be able to tolerate. The therapist should review physical therapy reports and confer with the PT as needed about gait techniques, aids, orthotics, and ambulatory status. To prepare the client for functional ambulation, the therapist and the client should have safe and appropriate footwear. Soft-soled shoes or shoes with a slippery sole should be avoided, and slippers or shoes without a heel support can compromise safety and stability for the client.

Another key to safe and successful ADLs is awareness of the client’s endurance level, including the distance the client is able to ambulate. It is very important to plan ahead for the activity. The therapist should have a wheelchair, a chair, or a stool readily available for use at appropriate intervals or in case of need caused by client fatigue. The area should be free of potential safety hazards, such as throw rugs or other objects on the floor. In certain cases, however, as with a client with unilateral neglect, hemianopsia, or visual or perceptual deficits, the therapist may want to challenge the client to manage in a complex environment.

The client’s physiologic responses should be monitored during the activity. The therapist should be aware of the client’s precautions and should respond appropriately. Physiologic responses may include a change in breathing patterns, perspiration, reddened or pale skin, a change in mental status, and decreased responsiveness. These changes may require termination of the activity to allow the client a period of rest. Recall that Pyia continues to experience limited endurance and easily fatigues. Activities that require sustained standing or walking may be too challenging at this time.

Elderly clients who use assistive devices for ambulation before hospitalization are particularly at risk for loss of ADL and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) function after hospitalization. A history of use of assistive devices may be a marker for decreased ability to recover.98 It may be important to target these elderly for intensive therapy to maintain function.

Falls represent a major problem in the elderly. Studies suggest that one fourth of persons aged 65 to 79 and half of those older than 80 fall every year.48 Falls result from many factors, including both intrinsic (e.g., health, existence of balance disorders) and external, or environmental, factors. Home hazards include poor lighting, inadequate bathroom grab rails, inadequate stair rails, exposed electrical cords, items on the floors, and throw rugs. Elderly people with health problems such as cardiac disease, stroke, and degenerative neurologic conditions have an even greater risk of falling.93,133 OTs may visit the client’s home while the client is hospitalized or may work through home health agencies, fall prevention programs, or senior citizen centers to help evaluate homes for potential hazards.115 All reasonable efforts should be made to decrease the risk of falls.

If a client loses his or her balance or stumbles, the therapist will have better control of the client if he or she is holding onto the client’s trunk. Therapists may be less prone to injure their own backs if they are using their legs to support or lower the client to the floor instead of pulling or twisting with the upper body. For a client who feels faint or develops sudden leg weakness, the therapist lowers the client onto the therapist’s flexed leg, like onto a chair, then down to the floor.

Functional Ambulation

Functional ambulation integrates ambulation into ADLs and IADLs. By using an occupationally based approach, the OT assesses the client’s abilities within the performance context and with an understanding of client habits, routines, and roles. What role(s) does the client have or want to have? What tasks does this role require? The OT plans for functional mobility activities with the goal of helping the client achieve valued roles and activities. Several typical functional ambulation activities follow. These activities must be individualized for clients. Functional ambulation may be incorporated during ADLs, IADLs, work, play, or leisure activities.

Kitchen Ambulation

Meal preparation and cleanup involve many different tasks, such as opening and reaching into a refrigerator, dishwasher, stove, microwave, and cupboards. This often involves transporting items within the kitchen and to a table. If something is dropped, the item will need to be retrieved from the floor. The task may be relatively quick and easy, such as heating food in a microwave, or may require someone to stand while chopping, stirring, or cooking food. The OT can help the client engage in problem-solving strategies on how to safely accomplish these tasks. For example, clients with left hemiplegia who ambulate with a quad cane may be guided to the left of the oven so that they can open the oven door by using the unaffected right upper extremity. The same concept should be kept in mind for opening cabinet doors or drawers or refrigerator doors. The therapist can help assess the client’s safety during these tasks and can recommend alternatives as needed. If the client is unable to successfully balance and reach into the oven, a toaster oven on the counter may be a safer alternative. Clients can place frequently needed items in convenient locations, or equipment such as a reacher may be needed. If the reacher is applied to a walker with Velcro, it is usually available when the client needs it. Clients may be able to pick up items from the floor by kicking or pushing the item close to a counter, where they can hold onto the counter while bending to pick up the item. If they have had a total hip replacement and have hip flexion precautions, they can position the affected leg behind them, being careful to not internally rotate the hip, while they reach down to the floor.

Transporting items such as food, plates, and eating utensils during functional ambulation invites creative problem solving on the part of the OT, particularly when the client is using an ambulation aid (Figures 11-1 and 11-2). Baskets attached to a walker, rolling carts, or countertops on which to slide the item may be appropriate in these situations. Clients must clearly desire the equipment or adaptations, and care should be taken not to provide unwanted or unnecessary equipment. A client who does not live alone may prefer to share jobs with other family members, that is, the client may do the cooking while a family member sets and clears the table. Although Pyia was able to prepare a simple meal, she still experiences fatigue after doing so and is unable to assist her daughter in meal preparation. Suggestions regarding adaptations and energy conservation techniques may support Pyia’s goal of being able to help with this activity while still living with her daughter.

Bathroom Ambulation

Functional ambulation to the sink, toilet, bathtub, or shower is an important concern for the client. Care should be taken during activities in the bathroom because of the many risks associated with water and hard surfaces. Spills on the floor are slipping hazards, and loose bath mats are tripping hazards. Clients must be educated about these dangers. Nonslip surfaces or mats should be used on tub and shower floors.

Functional ambulation to the sink using a walker may be performed by having the client approach the sink as closely as possible. If the walker has a walker basket, the client can position the walker at the side of the sink; then while holding onto the walker with one hand and the sink or countertop with the other, the patient can turn to face the sink.

The importance of helping the client become as independent as possible in toileting cannot be overemphasized. People who are unsure about their abilities to safely use a toilet in friends’ or families’ homes, in restaurants, in the mall, or at gas stations may become homebound as a result. When safe to do so, practice toileting in a variety of settings and with and without equipment such as commodes or elevating toilet seats and grab bars. One limiting factor may be postoperative precautions: A tall client who has had a total hip replacement may not be able to sit safely on a regular toilet while observing the postsurgical precaution of no hip flexion greater than 90 degrees. A shorter client may be able to sit successfully on a toilet of regular height without difficulty. If a client is unable to get up and down from the toilet without assistance, or if he or she does so with difficulty, consult the PT, who can provide the client with lower extremity strengthening exercises.

When the client is ambulating to a tub or shower, make sure the equipment and supplies are in position for the client to use. While stepping into a shower stall with a low rim, clients use the same technique that they would use to go up a curb or step, using their walking aid if it fits into the door of the shower. If the walking aid does not fit, the therapist can evaluate the client’s ability to safely step in without the equipment. A client who has non–weight-bearing precautions on a leg will not be able to step into a shower without walking aids, and will not step into a tub. A tub bench must be used for non–weight-bearing clients who have access only to tubs. Pyia is able to negotiate her daughter’s home and to use the toilet but still requires assistance to transfer into and out of the tub. These skills will have to be addressed before Pyia can return to her own home.

Grab bars are important safety items for clients in the shower and tub. The therapist may want to practice shower or tub transfers under trial conditions before practicing an actual shower or bath. Some older persons have become accustomed to taking sponge baths because of a fear of falling in the bathroom. The therapist should determine whether the client is satisfied with this system or would like to work toward independent showering.

Home Management Ambulation

The ability to live alone is closely tied to the ability to perform IADLs.96 Home management activities include cleaning, laundry, and household maintenance. Cleaning includes tidying, vacuuming, sweeping and mopping floors, dusting, and making beds. Clients may balance with one hand and hold onto a counter or a sturdy piece of furniture while cleaning floors if they are not stable independently or are using a walking aid. Lightweight duster-style sweepers, which come with dry or wet replaceable pads, are easy to handle and use. When making the bed, the client can stabilize himself or herself on the bed or walking aid while straightening and pulling up sheets and bedcovers. The client then moves around the bed to the other side to repeat the process. Some clients find that carrying items in a small fanny pack or shoulder bag slung over the neck is an easy way to transport small items such as cordless phones, bottled water, and books. Moving clothes to or from a laundry room may present a challenge for people with mobility impairments, particularly if they use a walking aid. Rolling carts may be useful to transport items to the laundry and in the kitchen. Some clients carry items over the front of their walkers, in a bag attached to the walker, or in a bag that they hold while walking with crutches or a cane. Whichever method is safe for the client is acceptable. Watch to make sure that the clothes do not shift while clients carry them; this may throw them off balance.

Other home management activities may include maintenance of the yard, garden, appliances, and vehicles. The client should be consulted to determine the home management activity most valued by the client before the functional activity is begun. Sometimes the client has goals that the therapist does not believe are safe for the client to perform. For example, the client who has had a mild stroke who wants to climb a ladder and trim tree branches with his power saw may need to be persuaded to wait until his balance and strength are improved. Although this is a valued activity, it may be incompatible with the client’s functional abilities at the time. Gardening is an area in which the PT and the OT may wish to collaborate. The PT helps the client learn to maneuver over uneven surfaces and get up and down from the ground, whereas the OT helps the client learn how to carry tools and other equipment and how to dispose of clippings and weeds.

In case of falls, clients should learn how to get up and down from the floor or ground during physical therapy sessions. It may be a functional activity with the OT when clients want to be able to get to the bottom of a tub, reach objects stored under a bed, or sit on the floor to play with their grandchildren.

Therapists should listen to clients about the techniques that clients have developed to be independent and safe. Some clients with fall risks manage to walk to the bathroom from their bed every night without putting on braces and/or using equipment. They will say things such as, “I lean against the wall as I walk,” or “There is a couch there, and I brace myself on the back.” If the technique is safe, and if the client has not had falls, the routine may not need modification.

Summary

Functional ambulation may be incorporated during ADLs, IADLs, work and productive activities, and play or leisure. OTs and PTs have an opportunity to collaborate, with the PT providing gait training, exercises, and ambulation aid recommendations, and the OT reinforcing training and integrating it during purposeful activities.

Section 2 Wheelchair Assessment and Transfers

MICHELLE TIPTON-BURTON with contributions from CAROL ADLER

Wheelchairs

A wheelchair can be the primary means of mobility for someone with a permanent or progressive disability such as cerebral palsy, brain injury, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, or muscular dystrophy. Someone with a short-term illness or orthopedic problem may need it as a temporary means of mobility. In addition to mobility, the wheelchair can substantially influence total body positioning, skin integrity, overall function, and the general well-being of the client. Regardless of the diagnosis of the client’s condition, the OT must understand the complexity of wheelchair technology, available options and modifications, the evaluation and measuring process, the use, care, and cost of the wheelchair, and the process by which this equipment is funded.

Wheelchairs have evolved considerably in recent years, and significant advances have been made in powered and manual wheelchair technology by manufacturers and service providers. Products are constantly changing. Many improvements are the result of user and therapist recommendations.

OTs and PTs, depending on their respective roles at their treatment facilities, are usually responsible for evaluation, measurement, and selection of a wheelchair and seating system for the client. They also teach wheelchair safety and mobility skills to clients and their caregivers. The constant evolution of technology and the variety of manufacturers’ products make it advisable to include an experienced, knowledgeable, and certified assistive technology practitioner (ATP) on the ordering team. The ATP is a supplier of durable medical equipment (DME) who is proficient in ordering custom items and can offer an objective and broad mechanical perspective on the availability and appropriateness of the options being considered. The ATP will serve as the client’s resource for insurance billing, repairs, and reordering upon returning to the community.

Whether the client requires a noncustom rental wheelchair for temporary use or a custom wheelchair for use over many years, an individualized prescription clearly outlining the specific features of the wheelchair is needed to ensure optimal performance, safety, mobility, and enhancement of function. A wheelchair that has been prescribed by an inexperienced or nonclinical person is potentially hazardous and costly to the client. An ill-fitting wheelchair can, in fact, contribute to unnecessary fatigue, skin breakdown, and trunk or extremity deformity, and it can inhibit function.49 A wheelchair is an extension of the client’s body and should facilitate rather than inhibit good alignment, mobility, and function.

Wheelchair Assessment

The therapist has considerable responsibility in recommending the wheelchair appropriate to meet immediate and long-term needs. When evaluating for a wheelchair, the therapist must know the client and have a broad perspective of the client’s clinical, functional, and environmental needs. Careful assessment of physical status must include the following: the specific diagnosis, the prognosis, and current and future problems (e.g., age, spasticity, loss of range of motion [ROM], muscle weakness, reduced endurance) that may affect wheelchair use. Additional client factors to be considered in assessment of wheelchair use are sensation, cognitive function, and visual and perceptual skills. Functional use of the wheelchair in a variety of environments must be considered. Collaboration with representatives of other disciplines treating the client is important. Box 11-1 lists questions to consider before making specific recommendations.

Before the final prescription is prepared, collected information must be analyzed for an understanding of advantages and disadvantages of recommendations based on the client’s condition and how all specifics will integrate to provide an optimally effective mobility system.

To ensure that payment for the wheelchair is authorized, therapists should have an in-depth awareness of the client’s insurance DME benefits and should provide documentation with thorough justification of the medical necessity of the wheelchair and any additional modifications. Therapists must explain clearly why particular features of a wheelchair are being recommended. They must be aware of standard vs. “up charge” items, the cost of each item, and the effects of these items on the end product.

Wheelchair Ordering Considerations

Before selecting a specific manufacturer and the wheelchair’s specifications, the therapist should carefully analyze the following sequence of evaluation considerations.3,120,160

Propelling the Wheelchair

The wheelchair may be propelled in a variety of ways, depending on the physical capacities of the user. If the client is capable of self-propulsion by using his or her arms on the rear wheels of the wheelchair, sufficient and symmetric grasp, arm strength, and physical endurance may be assumed present to maneuver the chair independently over varied terrain throughout the day.160 An assortment of push rims are available to facilitate self-propelling, depending on the user’s arm and grip strength. A client with hemiplegia may propel a wheelchair using the extremities on the unaffected side for maneuvering. A client with tetraplegia may have functional use of only one arm and may be able to propel a one-arm drive wheelchair, or a power chair may be more appropriate. Although William, the 17-year-old who has a C6 spinal cord injury, has functional strength in both biceps, energy and potential injury in the future must be considered if he is to use only a manual wheelchair.

If independence in mobility is desired, a power wheelchair should be considered for those who have minimal or no use of the upper extremities, limited endurance, or shoulder dysfunction. Power chairs are also preferred in situations involving inaccessible outdoor terrain.160 Power wheelchairs have a wide variety of features and can be programmed; driven by foot, arm, head, or neck; or pneumatically controlled (sip and puff), or even controlled by eye gaze. Given current sophisticated technology, assuming intact cognition and perception, even a person with the most severe physical limitations is capable of independently driving a power wheelchair.

If the chair is to be propelled by the caregiver, consideration must be given to ease of maneuverability, lifting, and handling, in addition to the positioning and mobility needs of the client.

Regardless of the method of propulsion, serious consideration must be given to the effect the chair has on the client’s current and future mobility and positioning needs. In addition, lifestyle and home environment, available resources such as ability to maintain the chair, transportation options, and available reimbursement sources are major determining factors. Although William is physically fit, his upper body strength has been compromised by the spinal cord injury. If he is interested in engaging in outdoor activities, he may lack the physical strength to propel a manual wheelchair on varied terrains. A powered wheelchair seemed an appropriate option for William, but the therapist also considered his previous occupations of camping and hiking when selecting a wheelchair that could potentially be used in outdoor terrain.

Rental vs. Purchase

The therapist should estimate how long the client will need the chair and whether the chair should be rented or purchased; this will affect the type of chair being considered. This decision is based on several clinical and functional issues. A rental chair is appropriate for short-term or temporary use, such as when the client’s clinical picture, functional status, or body size is changing. Rental chairs may be necessary when the permanent wheelchair is being repaired. A rental wheelchair also may be useful when prognosis and expected outcome are unclear, or when the client has difficulty accepting the idea of using a wheelchair and needs to experience it initially as a temporary piece of equipment. Often the eventual functional outcome is unknown. In this case, a chair can be rented for several months until a re-evaluation determines whether a permanent chair will be necessary.3

A permanent wheelchair is indicated for the full-time user and for the client with a progressive need for a wheelchair over a long period. It may be indicated when custom features are required or when body size is changing, such as in the growing child.3

Frame Style

Once the method of propulsion and the permanence of the chair have been determined, several wheelchair frame styles are available for consideration. The frame style must be selected before specific dimensions and brand names can be determined. The therapist needs to be aware of the various features, the advantages and disadvantages of each, and the effects of these features on the client in every aspect of his of her life, from a short-term and a long-term perspective. William is still in emotional shock that he no longer has motor control of his legs and hands. These variables must be considered when William is approached about wheelchair selection. Although a power wheelchair seemed the most appropriate choice for William, the therapist was concerned about the appearance of the wheelchair. The therapist actively engaged William in making choices regarding the type, model, and options available on various wheelchairs.

Wheelchair Selection

The following questions regarding client needs should be considered carefully before the specific type of chair is determined.3

Manual vs. Electric/Power Wheelchairs

Manual Wheelchair: See Figure 11-3, A.

FIGURE 11-3 Manual vs. electric wheelchair. A, Rigid frame chair with swing-away footrests. B, Power-driven wheelchair with hand control. (A, Courtesy Quickie Designs; B, courtesy Invacare Corporation.)

• Does the user have sufficient strength and endurance to propel the chair at home and in the community over varied terrain?

• Does manual mobility enhance functional independence and cardiovascular conditioning of the wheelchair user?

• Will the caregiver be propelling the chair at any time?

• What will be the long-term effects of the propulsion choice?

Power Chairs: Power chair controls come in a number of designs and allow for varying degrees of customization and programming. Most power chair users drive using a joystick control mounted on the armrest. For those without upper extremity function, several other types of controls are available, such as head controls, chin drives, and breath controls (sip and puff). New technology even accommodates a client with only eye or tongue movement that can be used to operate a power wheelchair (Figure 11-3, B).

• Does the user demonstrate insufficient endurance and functional ability to propel a manual wheelchair independently?

• Does the user demonstrate progressive functional loss, making powered mobility an energy-conserving option?

• Is powered mobility needed to enhance independence at school, at work, and in the community?

• Does the user demonstrate cognitive and perceptual ability to safely operate a power-driven system?

• Does the user or caregiver demonstrate responsibility for care and maintenance of equipment?

• Is a van available for transportation?

• Is the user’s home accessible for use of a power wheelchair?

• Has the user been educated regarding rear, mid, and front wheel drive systems, and has he or she been guided objectively in making the appropriate selection?

Manual Recline vs. Power Recline vs. Tilt Wheelchairs

Manual Recline Wheelchair: See Figure 11-4, A.

Power Recline vs. Tilt: See Figure 11-4, B and C.

FIGURE 11-4 Manual recline vs. power recline wheelchair. A, Reclining back on folding frame. B, Low-shear power recline with collar mount chin control on electric wheelchair. C, Tilt system with head control on electric wheelchair. (A, Courtesy Quickie Designs; B and C, courtesy Luis Gonzalez.)

• Does the client have the potential to operate independently?

• Are independent weight shifts and position changes indicated for skin care and increased sitting tolerance?

• Does the user demonstrate safe and independent use of controls?

• Are resources available for care and maintenance of the equipment?

• Does the user have significant spasticity that is facilitated by hip and knee extension during the recline phase?

• Does the user have hip or knee contractures that prohibit his or her ability to recline fully?

• Will a power recline or tilt decrease or make more efficient use of caregiver time?

• Will a power recline or tilt feature on the wheelchair reduce the need for transfers to the bed for catheterizations and rest periods throughout the day?

• Will the client require quick position changes in the event of hypotension and/or dysreflexia?

• Has a reimbursement source been identified for this add-on feature?

Folding vs. Rigid Manual Wheelchairs

Folding Wheelchairs: See Figure 11-5, A.

FIGURE 11-5 Folding vs. rigid wheelchair. A, Lightweight folding frame with swing-away footrests. B, Rigid aluminum frame with tapered front end and solid foot cradle. (A, Courtesy Quickie Designs; B, courtesy Invacare Corporation.)

• Is the folding frame needed for transport, storage, or home accessibility?

• Which footrest style is necessary for transfers, desk clearance, and other daily living skills? Elevating footrests are available only on folding frames.

• Is the client or caregiver able to lift, load, and fit the chair into necessary vehicles?

• Equipment suppliers should have knowledge and a variety of brands available. Frame weight can range approximately from 28 to 50 lb, depending on size and accessories. Frame adjustments and custom options vary with the model.

Rigid Wheelchairs: See Figure 11-5, B.

• Does the user or caregiver have the upper extremity function and balance needed to load and unload the nonfolding frame from a vehicle if driving independently?

• Will the user benefit from the improved energy efficiency and performance of a rigid frame?

Footrest options are limited and the frame is lighter (20 to 35 lb). Features include an adjustable seat angle, rear axle, caster mount, and back height. Efficient frame design maximizes performance. Options are available for frame material composition, frame colors, and aesthetics. These chairs are usually custom ordered; availability and expertise are generally limited to custom rehabilitation technology suppliers.

Lightweight (Folding or Nonfolding) vs. Standard-Weight (Folding) Wheelchairs

Lightweight Wheelchairs: Under 35 Pounds: See Figure 11-5, A.

• Does the user have the trunk balance and equilibrium necessary to handle a lighter frame weight?

• Does the lighter weight enhance mobility by reducing the user’s fatigue?

• Will the user’s ability to propel the chair or handle parts be enhanced by a lighter-weight frame?

• Are custom features (e.g., adjustable height back, seat angle, axle mount) necessary?

Standard-Weight Wheelchairs: More Than 35 Pounds: See Figure 11-6.

FIGURE 11-6 Standard folding frame (>35 lb) with swing-away footrests. (Courtesy Everest & Jennings, Inc.)

• Does the user need the stability of a standard-weight chair?

• Does the user have the ability to propel a standard-weight chair?

• Can the caregiver manage the increased weight when loading the wheelchair and fitting into a vehicle?

• Will the increased weight of parts be unimportant during daily living skills?

Custom options are limited, and these wheelchairs are usually less expensive (except heavy-duty models required for users weighing more than 250 lb).

Standard Available Features vs. Custom, Top-of-the-Line Models

The price range, durability, and warranty within a specific manufacturer’s model line must be considered.

• Is the chair required only for part-time use?

• Does the user have a limited life expectancy?

• Is the chair needed as a second or transportation chair, used only 10% to 20% of the time?

• Will the chair be primarily for indoor or sedentary use?

• Is the user dependent on caregivers for propulsion?

• Will the chair be propelled only by the caregiver?

For standard wheelchairs, a limited warranty is available on the frame. These chairs may be indicated because of reimbursement limitations. Limited sizes and options and adjustability are available. These cost considerably less than custom wheelchairs.

Custom and Top-of-the-Line Models:

• Will the client be a full-time user?

• Is long-term use of the wheelchair a likely prognosis?

• Will this be the primary wheelchair?

• Is the user active indoors and outdoors?

• Will this frame style improve prognosis for independent mobility?

• Is the user a growing adolescent, or does he or she have a progressive disorder requiring later modification of the chair?

• Are custom features, specifications, or positioning devices required?

Top-of-the-line wheelchair frames usually have a lifelong warranty on the frame. A variety of specifications, options, and adjustments are available. Many manufacturers will work with therapists and providers to solve a specific fitting problem. Experience is essential in ordering top-of-the-line and custom equipment.

Wheelchair Measurement Procedures

The client is measured in the style of chair and with the seat cushion that most closely resembles those being ordered. If the client will wear a brace or body jacket or will need any additional devices in the chair, these should be in place during the measurement. Observation skills are important during this process. Measurements alone should not be used. The therapist should visually assess and monitor the client’s entire body position throughout the measurement process.3,159

Seat Width

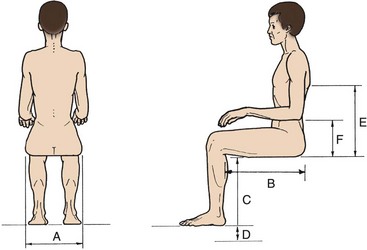

See Figure 11-7, A.

FIGURE 11-7 Measurements for wheelchairs. A, Seat width. B, Seat depth. C, Seat height from floor. D, Footrest clearance. E, Back height. F, Armrest height. (Adapted from Wilson A, McFarland SR: Wheelchairs: a prescription guide, Charlottesville, Va, 1986, Rehabilitation Press.)

Measurements: Measure the individual across the widest part of the thighs or hips while the client is sitting in a chair comparable with the anticipated wheelchair.

Wheelchair Clearance: Add  to 1 inch on each side of the hip or thigh measurement taken. Consider how an increase in the overall width of the chair will affect accessibility.

to 1 inch on each side of the hip or thigh measurement taken. Consider how an increase in the overall width of the chair will affect accessibility.

Checking: Place the flat palm of the hand between the client’s hip or thigh and the wheelchair skirt and armrest. The wheelchair skirt is attached to the armrests in many models, and clearance should be sufficient between the user’s thigh and the skirt to avoid rubbing or pressure.

Seat Depth

See Figure 11-7, B.

Objective: The objective is to distribute the body weight along the sitting surface by bearing weight along the entire length of the thigh to just behind the knee. This approach is necessary to help prevent pressure sores on the buttocks and the lower back, and to attain optimal muscle tone normalization to assist in prevention of pressure sores throughout the body.

Measurements: Measure from the base of the back (the posterior buttocks region touching the chair back) to the inside of the bent knee; the seat edge clearance needs to be 1 to 2 inches less than this measurement.

Checking: Check clearance behind the knees to prevent contact of the front edge of the seat upholstery with the popliteal space. (Consider front angle of leg-rest or foot cradle.)

• Braces or back inserts may push the client forward.

• Postural changes may occur throughout the day from fatigue or spasticity.

• Thigh length discrepancy: the depth of the seat may be different for each leg.

• If considering a power recliner, assume that the client will slide forward slightly throughout the day, and make depth adjustments accordingly.

• Seat depth may need to be shortened to allow independent propulsion with the lower extremities.

Seat Height from Floor and Foot Adjustment

1. To support the client’s body while maintaining the thighs parallel to the floor (Figure 11-7, C).

2. To elevate the foot plates to provide ground clearance over varied surfaces and curb cuts (Figure 11-7, D).

Measurements: The seat height is determined by measuring from the top of the wheelchair frame supporting the seat (the post supporting the seat) to the floor, and from the client’s popliteal fossa to the bottom of the heel.

Wheelchair Clearance: The client’s thighs are kept parallel to the floor, so the body weight is distributed evenly along the entire depth of the seat. The lowest point of the foot plates must clear the floor by at least 2 inches.

Checking: Slip fingers under the client’s thighs at the front edge of the seat upholstery. Note: A custom seat height may be needed to obtain footrest clearance. An inch of increased seat height raises the foot plate 1 inch.

Considerations: If the knees are too high, increased pressure at the ischial tuberosities puts the client at risk for skin breakdown and pelvic deformity. This position also impedes the client’s ability to maneuver the wheelchair using the lower extremities.

Posterior pelvic tilt makes it difficult to shift weight forward as needed to propel the wheelchair, especially with uphill grades.

Sitting too high off the ground can impair the client’s center of gravity, seat height for transfers, and visibility if driving a van from the wheelchair.

Back Height

See Figure 11-7, E.

Objective: Back support consistent with physical and functional needs must be provided. The chair back should be low enough for maximal function and high enough for maximal support.

Measurements: For full trunk support for the client, the back must be of sufficient height. Full support height is obtained by measuring from the top of the seat frame on the wheelchair (seat post) to the top of the user’s shoulders. For minimum trunk support, the top of the back upholstery is below the inferior angle of the client’s scapulae; this should permit free arm movement, should not irritate the skin or scapulae, and should provide good total body alignment.

Armrest Height

See Figure 11-7, F.

Measurements: With the client in a comfortable position, measure from the wheelchair seat frame (seat post) to the bottom of the user’s bent elbow.

Wheelchair Clearance: The height of the top of the armrest should be 1 inch higher than the height from the seat post to the user’s elbow.

Checking: The client’s posture should look appropriately aligned. The shoulders should not slouch forward or be subluxed or forced into elevation when the client is in a relaxed sitting posture, with flexed elbows resting slightly forward on armrests.

• Armrests may have other uses, such as increasing functional reach or holding a cushion in place.

• Certain styles of armrests can increase the overall width of the chair.

• Is the client able to remove and replace the armrest from the chair independently?

• Review all measurements against standards for a particular model of chair.

• Manufacturers have lists of the standard dimensions available and the costs of custom modifications.

Pediatrics

The goals of pediatric wheelchair ordering, as with all wheelchair ordering, should be to obtain a proper fit and to facilitate optimal function. Rarely does a standard wheelchair meet the fitting requirements of a child. The selection of size is variable; therefore custom seating systems specific to the pediatric population are available. A secondary goal is to consider a chair that will accommodate the child’s growth.

For children younger than 5 years of age, a decision must be made about whether to use a stroller base or a standard wheelchair base. Considerations include the child’s ability to propel the chair relative to his or her developmental level, and the parents’ preference for a stroller or a wheelchair.

Many variables must be considered when a wheelchair frame is customized. An experienced ATP or the wheelchair manufacturer should be consulted to ensure that a custom request will be filled successfully.

Bariatrics

According to the latest data from the National Center for Health Statistics, more than 30% of American adults 20 years of age and older (more than 60 million people) are obese.47 The average wheelchair is rated to hold up to 250 pounds, and most bariatric wheelchairs can accommodate 500 pounds. It is imperative that the therapist order a wheelchair that not only meets the client’s functional needs but will safely accommodate his or her weight. Utilizing a wheelchair for patients who exceed the weight limit has potential safety issues such as skin breakdown and the risk of wheelchair bending or buckling, which may cause injury to the client. Bariatric wheelchairs feature heavy duty frames, reinforced padded upholstery, and heavy duty wheels. An experienced supplier of DME should be able to guide the therapist and the client to the most appropriate and safe wheelchair.

Additional Seating and Positioning Considerations

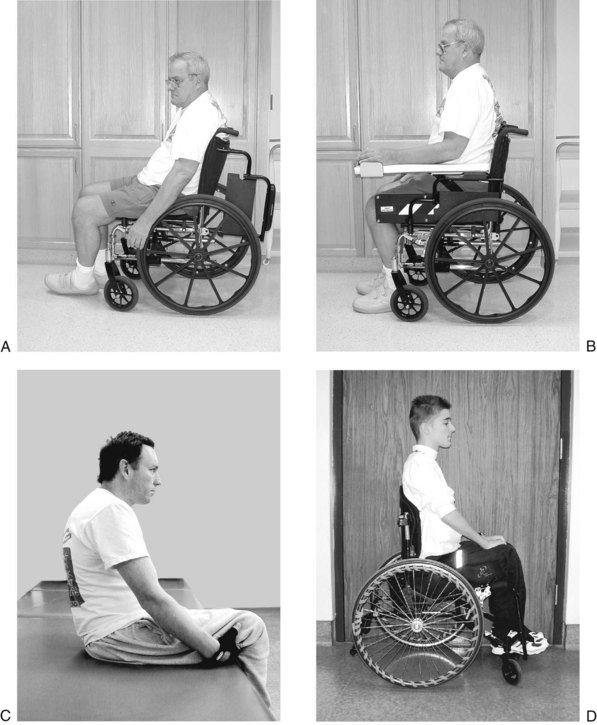

A wheelchair evaluation is not complete until the seat cushion, the back support, and any other positioning devices as well as the integration of those parts are carefully thought out, regardless of the diagnosis. The therapist must appreciate the effect that optimal body alignment has on skin integrity, tone normalization, overall functional ability, and general well-being (Figure 11-8).3

FIGURE 11-8 A, Client who had a stroke, seated in wheelchair. Poor positioning results in kyphotic thoracic spine, posterior pelvic tilt, and unsupported affected side. B, Same client now seated in wheelchair with appropriate positioning devices. Seat and back inserts facilitate upright midline position with neutral pelvic tilt and equal weight bearing throughout. C, Client who sustained a spinal cord injury sitting with back poorly supported results in posterior pelvic tilt, kyphotic thoracic spine, and absence of lumbar curve. D, Same client seated with rigid back support and pressure-relief seat cushion, resulting in erect thoracic spine, lumbar curve, and anterior tilted pelvis.

Consider William’s potential need for a wheelchair seat cushion that will distribute weight evenly and avoid excessive pressure on his ischial tuberosities while sitting. He lacks sensory awareness in the buttocks region, and that places him at risk for developing decubitus ulcers. He should develop sitting tolerance that extends beyond the current 1-hour time period to help him pursue his educational goals of attending college. An appropriate seat cushion that distributes weight evenly will help William remain seated for a longer period of time. He will also need to develop the habit of shifting his weight while seated. This can be done by having William position his arm around the upright posts of the wheelchair back and pulling his body slightly to one side and then repeating the process on the other side. This shifting of the body from side to side reduces the risk of developing decubitus ulcers.

Following are the goals of a comprehensive seating and positioning assessment.

Prevention of Deformity

Providing a symmetric base of support preserves proper skeletal alignment and discourages spinal curvature and other body deformities.

Tone Normalization

With proper body alignment, in addition to bilateral weight bearing and adaptive devices as needed, tone normalization can be maximized.

Pressure Management

Pressure sores can be caused by improper alignment and an inappropriate sitting surface. The proper seat cushion can provide comfort, assist in trunk and pelvic alignment, and create a surface that minimizes pressure, heat, moisture, and shearing—the primary causes of skin breakdown.

Promotion of Function

Pelvic and trunk stability is necessary to free the upper extremity for participation in all functional activities, including wheelchair mobility and daily living skills.

Maximum Sitting Tolerance

Wheelchair sitting tolerance will increase as support, comfort, and symmetric weight bearing are provided.

Optimal Respiratory Function

Support in an erect, well-aligned position can decrease compression of the diaphragm, thus increasing vital capacity.

Provision for Proper Body Alignment

Good body alignment is necessary for prevention of deformity, normalization of tone, and promotion of movement. The client should be able to propel the wheelchair and to move around within the wheelchair.

A wide variety of seating and positioning equipment is available for all levels of disability. Custom modifications are continually being designed to meet a variety of client needs. In addition, technology in this area is ever growing, as is interest in wheelchair technology as a professional specialty. However, the skill of clinicians in this field ranges from extensive to negligible. Although it is an integral aspect of any wheelchair evaluation, the scope of seating and positioning equipment is much greater than can be addressed in this chapter. The suggested reading list at the end of this chapter provides additional resources.

Accessories

Once the measurements and the need for additional positioning devices have been determined, a wide variety of accessories are available to meet a client’s individual needs. It is extremely important for the therapist to understand the function of each accessory and how an accessory interacts with the complete design and function of the chair and with seating and positioning equipment.3,160

Armrests come in fixed, flip-back, detachable, desk, standard, reclining, adjustable height, and tubular styles. The fixed armrest is a continuous part of the frame and is not detachable. It limits proximity to table, counter, and desk surfaces and prohibits side transfers. Flip-back, detachable desk, and standard-length arms are removable and allow side-approach transfers. Reclining arms are attached to the back post and recline with the back of the chair. Tubular arms are available on lightweight frames.

Footrests may be fixed, swing-away detachable, solid cradle, and elevating. Fixed footrests are attached to the wheelchair frame and are not removable. These footrests prevent the person from getting close to counters and may make some types of transfers more difficult. Swing-away detachable footrests can be moved to the side of the chair or removed entirely. This allows a closer approach to bed, bathtub, and counters, and, when the footrests are removed, reduces the overall wheelchair length and weight for easy loading into a car. Detachable footrests lock into place on the chair with a locking device.160 A solid cradle footrest is found on rigid, lightweight chairs and is not removable. Elevating leg rests are available for clients with such conditions as lower extremity edema, blood pressure changes, and orthopedic problems.

Foot plates may have heel loops and toe straps to aid in securing the foot to the foot plate.160 The angle of the footplate itself can be fixed or adjustable, raising or lowering toes relative to heels. A calf strap can be used on a solid cradle, or when additional support behind the calf is necessary. Other accessories can include seat belts, various brake styles, brake extensions, anti-tip devices, caster locks, arm supports, and head supports.

Preparing the Justification/Prescription

Once specific measurements and the need for modifications and accessories have been determined, the wheelchair prescription must be completed. It should be concise and specific so that everything requested can be accurately interpreted by the DME supplier, who will be submitting a sales contract for payment authorization. Before-and-after pictures can be helpful to illustrate medical necessity. The requirements for payment authorization from a particular reimbursement source must be known, so that medical necessity can be demonstrated. The therapist must be aware of the cost of every item being requested and must provide a reason and justification for each item. Payment may be denied if clear reasons are not given to substantiate the necessity for every item and modification requested.

Before the wheelchair is delivered to the client, the therapist should check the chair vs. the specific prescription and should ensure that all specifications and accessories are correct. When a custom chair has been ordered, the client should be fitted by the ordering therapist to ensure that the chair fits, and that it provides all the elements expected when the prescription was generated.

Wheelchair Safety

Wheelchair parts tend to loosen over time and should be inspected and tightened on a regular basis.

Elements of safety for the wheelchair user and the caregiver are as follows:

1. Brakes should be locked during all transfers.

2. The client should never weight bear or stand on the foot plates, which are placed in the “up” position during most transfers.

3. In most transfers, it is an advantage to have footrests removed or swung away if possible.

4. If a caregiver is pushing the chair, he or she should be sure that the client’s elbows are not protruding from the armrests and that the client’s hands are not on the hand rims. If approaching from behind to assist in moving the wheelchair, the caregiver should inform the client of this intent and should check the position of the client’s feet and arms before proceeding.

5. To push the client up a ramp, he or she should move in a normal, forward direction. If the ramp is negotiated independently, the client should lean slightly forward while propelling the wheelchair up the incline.161

6. To push the client down a ramp, the caretaker should tilt the wheelchair backward by pushing his or her foot down on the anti-tippers to its balance position, which is a tilt of approximately 30 degrees. Then the caregiver should ease the wheelchair down the ramp in a forward direction, while maintaining the chair in its balance position. The caregiver should keep his or her knees slightly bent and the back straight.161 The caregiver may also move down the ramp backward while the client maintains some control of the large wheels to prevent rapid backward motion. This approach is useful if the grade is relatively steep. Ramps with only a slight grade can be managed in a forward direction if the caregiver maintains grasp and pull on the hand grips, and the client again maintains some control of the big wheels to prevent rapid forward motion. If the ramp is negotiated independently, the client should move down the ramp facing forward, while leaning backward slightly and maintaining control of speed by grasping the hand rims. The client can descend a steep grade by traversing the ramp slightly back and forth to slow the chair. Push gloves may be helpful to reduce the effects of friction.161

7. A caregiver can manage ascending curbs by approaching them forward, tipping the wheelchair back, and pushing the foot down on the anti-tipper levers, thus lifting the front casters onto the curb and pushing forward. The large wheels then are in contact with the curb and roll on with ease as the chair is lifted slightly onto the curb.

8. The curb should be descended using a backward approach. A caregiver can move himself or herself and the chair around as the curb is approached and can pull the wheelchair to the edge of the curb. Standing below the curb, the caregiver can guide the large wheels off the curb by slowly pulling the wheelchair backward until it begins to descend. After the large wheels are safely on the street surface, the assistant can tilt the chair back to clear the casters, move backward, lower the casters to the street surface, and turn around.161

With good strength and coordination, many clients can be trained to manage curbs independently. To mount and descend a curb, the client must have good bilateral grip, arm strength, and balance. To mount the curb, the client tilts the chair onto the rear wheels and pushes forward until the front wheels hang over the curb, then lowers them gently. The client then leans forward and forcefully pushes forward on the hand rims to bring the rear wheels up on the pavement. To descend a curb, the client should lean forward and push slowly backward until the rear and then the front wheels roll down the curb.43

The ability to lift the front casters off the ground and balance on the rear wheels (“pop a wheelie”) is a beneficial skill that expands the client’s independence in the community with curb management, and in rural settings with movement over grassy, sandy, or rough terrain. The chair will have to be properly adjusted so that the axle is not too far forward, which makes the wheelchair tip over backward too easily. Clients who have good grip, arm strength, and balance usually can master this skill and perform safely. The technique involves being able to tilt the chair on the rear wheels, balance the chair on the rear wheels, and move and turn the chair on the rear wheels. Wheelies make it possible to wheel up or down (jump) curbs. The client should not attempt to perform these maneuvers without instruction and training in the proper techniques, which are beyond the scope of this chapter. Specific instructions on teaching these skills can be found in the sources cited at the end of the chapter.43

Transfer Techniques

Transferring is the movement of a client from one surface to another. This process includes the sequence of events that must occur both before and after the move, such as the pre-transfer sequence of bed mobility and the post-transfer phase of wheelchair positioning. If it is assumed that a client has some physical or cognitive limitations, it will be necessary for the therapist to assist in or supervise a transfer. Many therapists are unsure of the transfer type and technique to employ or feel perplexed when a particular technique does not succeed with the client. Each client, therapist, and situation is different. This chapter does not include an outline of all techniques but presents the basic techniques with generalized principles. Each transfer must be adapted for the particular client and his or her needs. Discussion in this chapter includes directions for some transfer techniques that are most commonly employed in practice. These techniques include the stand pivot, the bent pivot, and one-person and two-person dependent transfers.

Preliminary Concepts

The therapist must be aware of the following concepts when selecting and carrying out transfer techniques to ensure safety for the client and self:

1. The client’s status, especially his or her physical, cognitive, perceptual, and behavioral abilities and limitations.

2. His or her own physical abilities and limitations and whether he or she can communicate clear, sequential instructions to the client (and if necessary to the long-term caregiver of the client).

Guidelines for Using Proper Mechanics

The therapist should be aware of the following principles of basic body mechanics4:

1. Get close to the client or move the client close to you.

2. Position your body to face the client (face head on).

3. Bend the knees; use your legs, not your back.

4. Keep a neutral spine (not a bent or arched back).

5. Keep a wide base of support.

7. Don’t tackle more than you can handle; ask for help.

8. Don’t combine movements. Avoid rotating at the same time as bending forward or backward.

The therapist should consider the following questions before performing a transfer:

1. What medical precautions affect the client’s mobility or method of transfer?

2. Can the transfer be performed safely by one person, or is assistance required?

3. Has enough time been allotted for safe execution of a transfer? Are you in a hurry?

4. Does the client understand what is going to happen? If not, does he or she demonstrate fear or confusion? Are you prepared for this limitation?

5. Is the equipment (wheelchair, bed) that the client is being transferred to and from in good working order and in a locked position?

6. What is the height of the bed (or surface) in relation to the wheelchair? Can the heights be adjusted so that they are similar? Transferring downhill is easier than uphill.

7. Is all equipment placed in the correct position?

8. Are all unnecessary bedding and equipment (e.g., footrests, armrests) moved out of the way so that you are working without obstruction?

9. Is the client dressed properly in case you need to use a waistband to assist? If not, do you need a transfer belt or other assistance?

10. What are the other components of the transfer, such as leg management and bed mobility?

The therapist should be familiar with as many types of transfers as possible, so that each situation can be resolved as it arises.

Many classifications of transfers exist, based on the extent of therapist participation. Classifications range from dependent, in which the client is unable to participate and the therapist moves the client, to independent, in which the client moves independently while the therapist merely supervises, observes, or provides input for appropriate technique related to the client’s disabling condition.

Before attempting to move a client, the therapist must understand the biomechanics of movement and the effect the client’s center of positioning mass has on transfers.

Principles of Body Positioning

Pelvic Tilt: Generally, after the acute onset of a disability or prolonged time spent in bed, clients assume a posterior pelvic tilt (i.e., a slouched position with lumbar flexion). In turn, this posture moves the center of mass back toward the buttocks. The therapist may need to verbally cue or manually assist the client into a neutral or slightly anterior pelvic tilt position to move the center of mass forward over the center of the client’s body and over the feet in preparation for the transfer.132

Trunk Alignment: It may be observed that the client’s trunk alignment is shifted to the right or the left side. If the therapist assists in moving the client while the client’s weight is shifted to one side, this movement could throw the client and the therapist off balance. The client may need verbal cues or physical assistance to come to and maintain a midline trunk position before and during the transfer.

Weight Shifting: Transfer is initiated by shifting the client’s weight forward, thus removing weight from the buttocks. This movement allows the client to stand, partially stand, or be pivoted by the therapist. This step must be performed regardless of the type of transfer.

Lower Extremity Positioning: The client’s feet must be placed firmly on the floor with ankles stabilized and with knees aligned at 90 degrees of flexion over the feet. This position allows the weight to be shifted easily onto and over the feet. Heels should be pointing toward the surface to which the client is transferring. The client should be barefoot or should have shoes on to prevent slipping out of position. Shoes with proper ankle support are beneficial for patients who have weakness/instability in the ankles/feet. The feet can easily pivot in this position, and the risk of twisting or injuring an ankle or knee is minimized.

Upper Extremity Positioning: The client’s arms must be in a safe position or in a position in which he or she can assist in the transfer. If one or both of the upper extremities are nonfunctional, the arms should be placed in a safe position that will not be in the way during the transfer (e.g., in the client’s lap). If the client has partial or full movement, motor control, or strength, he or she can assist in the transfer by reaching toward the surface to be reached or by pushing off from the surface to be left. The decision to request the client to use the arms during the transfer is based on the therapist’s prior knowledge of the client’s motor function. The client should be encouraged to not reach or grab for the therapist during the transfer, as this could throw balance off.

Preparing Equipment and Client for Transfer

The transfer process includes setting up the environment, positioning the wheelchair, and helping the client into a pre-transfer position. The following is a general overview of these steps.

Positioning the Wheelchair

1. Place the wheelchair at approximately a 0- to 30-degree angle to the surface to which the client is transferring. The angle depends on the type of transfer and the client’s level of assist.

2. Lock the brakes on the wheelchair and the bed.

3. Place both of the client’s feet firmly on the floor, hip width apart, with knees over the feet.

4. Remove the wheelchair armrest closer to the bed.

5. Remove the wheelchair pelvic seat belt.

6. Remove the wheelchair chest belt and trunk or lateral supports if present.

Bed Mobility in Preparation for Transfer

Rolling the Client Who Has Hemiplegia:

1. Before rolling the client, you may need to put your hand under the client’s scapula on the weaker side and gently mobilize it forward (into protraction) to prevent the client from rolling onto the shoulder, potentially causing pain and injury.

2. Assist the client in clasping the strong hand around the wrist of the weak arm, and lift the upper extremities upward toward the ceiling.

3. Assist the client in flexing his or her knees.

4. You may assist the client to roll onto his or her side by moving first the arms toward the side, then the legs, and finally by placing one of the therapist’s hands at the scapular area and the other therapist’s hand at the hip, guiding the roll.