Sleep and Rest

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

1 Define normal sleep architecture in the young adult population.

2 Describe how sleep architecture changes across the life span.

3 Describe the difference between sleep and rest.

4 Describe at least five negative consequences of poor sleep and rest on daily occupations.

5 Name at least seven techniques to promote good sleep hygiene techniques that will optimize conditions to facilitate sleep.

6 Describe the role of the occupational therapy practitioner in sleep and rest.

The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF) is an official document of the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA), the national organization that represents occupational therapy in the United States.7 The OTPF is reviewed every 5 years and is considered an evolving document. In the original OTPF,5 seven performance areas in which humans engage were identified. The performance areas included activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental ADLs (IADLs), education, work, play, leisure, and social participation. Sleep and rest was organized under the category of ADLs. Several revisions were made in the second edition of the framework (the OTPF-2) after feedback received from researchers, practitioners, and scholars. One change included a recategorization of sleep and rest.

According to the second edition of the OTPF (referred to as the OTPF-2), sleep and rest is now considered to be one of the eight main areas of occupations in which humans may engage. The categorization of sleep and rest as its own occupational performance area was made for several reasons.

The rationale for this change was that “[r]est and sleep are two of the four main categories of occupation discussed by Adolf Meyer.64 Unlike any other area of occupation, all people rest as a result of engaging in occupations and engage in sleep for multiple hours per day throughout their life span” (p. 665).7 As cited in the OTPF-2,7 other rationales included the fact that “[s]leep significantly affects all other areas of occupation. Jonsson54 suggested that providing sleep prominence in the framework as an area of occupation will promote the consideration of lifestyle choices as an important aspect of participation and health” (p. 665).7

With sleep and rest considered a performance area in the occupational therapy domain, it is appropriate for an occupational therapist to address sleep and rest when treating Mrs. Tanaka.

History of Sleep and Rest in Occupational Therapy

From the earliest published writings in occupational therapy, sleep was considered to be important. In October 1921, Adolf Meyer, presenting a paper at the fifth annual meeting of the National Society for the Promotion of Occupational Therapy (now known as the American Occupational Therapy Association) stated (1922):64

There are many other rhythms which we must be attuned to: the larger rhythms of night and day, of sleep and waking hours, or hunger and its gratification, and finally the big four—work and play and rest and sleep, which our organism must be able to balance in all this is actual doing, actual practice, a program of wholesome living as the basis of wholesome feeling and thinking and fancy and interests. (p. 6)

Despite the founders of occupational therapy considering sleep and rest to be important for a healthy balance in life, the area of sleep and rest seems to have been forgotten in the occupational therapy literature as well as in the profession’s practice.

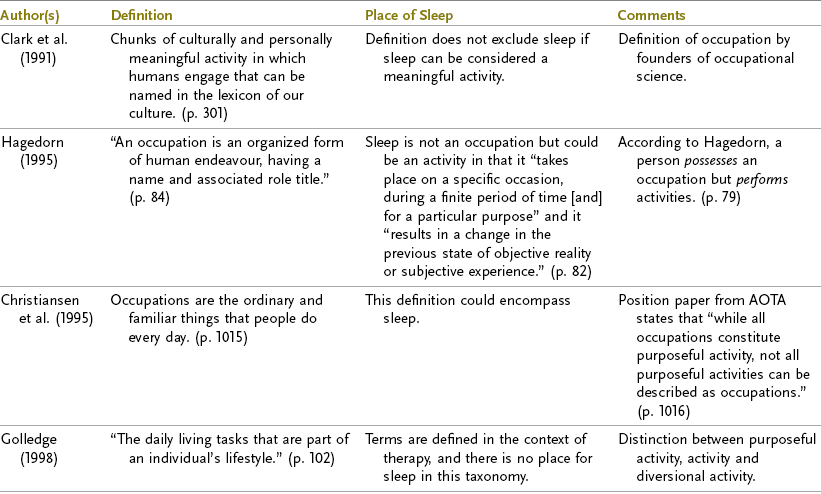

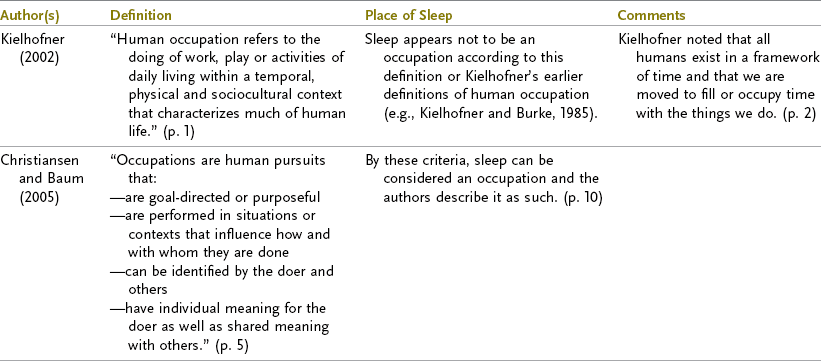

Green has suggested that occupational therapy has paid little attention to the area of sleep because influential scholars in the field have omitted sleep definitions from classifications of occupations41 (Table 13-1). Green also noted that occupational scientists are uncertain about whether sleep is considered an occupation. In his research, Green found evidence in the occupational science literature on sleep with respect to time use and of occupational therapists giving advice on sleep. However, he noted, “Coverage has been neither consistent nor comprehensive and it is unclear why sleep has been considered by so few writers” (p. 342).

TABLE 13-1

Some Definitions of Occupation and Relationship of Sleep

From Green A: Sleep, occupation and the passage of time, Br J Occup Ther 71(8):343, 2008.

Howell and Pierce suggested that Meyer’s ideas about the importance of the occupations of sleep and rest were not embraced or further developed in occupational therapy because of the culture’s overemphasis on productivity in industry, business, home management, and even leisure.49 The authors believe that the Protestant work ethic, Industrial Revolution, and Victorian era all played a role to shape current Western views on restorative occupations. They pointed out that Meyer’s message was “ignored” in Western society because “it is generally believed that valuable time is wasted while sleeping, time that could be spent more productively” (p. 68).49

In a review of occupational therapy textbooks published since 1990, Green found that information on sleep was limited.41 He pointed out, however, that Yasuda94 and Hammond and Jefferson44 addressed the topic more thoroughly in chapters regarding fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis, respectively. Now that sleep and rest are identified as a separate occupational performance area in the OTPF-2, it is anticipated that educational programs will cover the area of sleep and rest even more thoroughly in their curriculums. Jonsson further suggested that the prominence of sleep and rest as an occupational performance area in the OTPF-2 will highlight the importance of this area of occupation to lifestyle choices for participation and health.54

It should be considered that occupational therapists may be so busy helping patients on areas of occupations when the client is awake that focusing on the area of sleep may be given lower priority. For example, the areas an occupational therapist needs to address for Mrs. Tanaka are numerous and can be overwhelming for a novice and even experienced occupational therapist with time pressures for clients to meet functional and other occupational goals.

Given the previously mentioned revision of the OTPF it is expected that the profession will now accord the matter of sleep and rest the attention it deserves as a main area of occupation. Additionally, educators have a new document by the AOTA, the Blueprint for Entry-Level Education,8 which identifies key content areas that occupational therapy students should receive in their education. The topic of sleep and rest was included on the list of occupation-centered factors that should be included in entry-level curriculum content for students.

Occupational Therapy Definition of Sleep and Rest

The OTPF-2 defines sleep as “[a] natural periodic state of rest for the mind and body, in which the eyes usually close and consciousness is completely or partially lost, so that there is a decrease in bodily movement and responsiveness to external stimuli.”7 During sleep the brain in humans and other mammals undergoes a characteristic cycle of brain-wave activity that includes intervals of dreaming.7,86 The OTPF includes in its definition of sleep that consciousness could be “completely” lost. Sleep researcher Mahowald,60 however, stated, “There is now overwhelming evidence that the primary states of being (wakefulness, NREM sleep and REM sleep) are not mutually exclusive, but may become admixed or may oscillate rapidly, resulting in numerous clinical phenomena” (p. 159). Coren,26 another sleep scientist, pointed out that at some level our vision, hearing, and sense of touch are still functioning to some extent when asleep. Human sleep is not just the opposite of wakefulness or wakefulness the opposite of sleep.61 It appears that consciousness is not completely lost during sleep.

Rest

As cited in the OTPF,7 rest is defined as “[q]uiet and effortless actions that interrupt physical and mental activity, resulting in a relaxed state” (p. 227).73 According to the OTPF-2,7 rest includes identifying a need to rest and relax, reducing involvement in taxing (physically, mentally, or socially) activities, and participating in relaxation or other endeavors that restore energy, calm, and renewed interest and engagement.

Nurit and Michal compared how the literature of the various fields that interact with occupational therapy conceptualize rest.73 Psychology, they pointed out, considers rest a basic human need,62 whereas the nursing profession differentiates between physical and mental rest. Various religions and philosophies view rest as important for restoration and focus. The researchers concluded that though the various fields may have different concepts of rest, they all concur with occupational therapy that rest is important for a healthy, balanced life.

Nurit and Michal also reviewed debates surrounding the concept of “bed rest” in medicine;73 they cited that historically rest was highly recommended.18 They pointed to research that has shown that clients on bed rest, when compared to those clients in ambulatory groups, may experience detrimental effects to their health.3 In this chapter, the focus is on the general concept of rest as opposed to the idea of physician ordered “bed rest” when a patient may not be allowed out of bed for medical or safety reasons.

Sleep and Rest

The OTPF-2 explains that the concept of both sleep and rest “includes activities related to obtaining restorative rest and sleep that supports healthy active engagement in other areas of occupation” (p. 632).7 Instead of categorizing the occupations into what she has called “adopted cultural categories” (p. 45)78 of work, play, leisure, and self-care, Pierce described the categories of occupation based on how the individual experiences them. She described three categories of occupation as pleasurable, which includes play and leisure; productive, which includes work; and restorative types of occupations, which includes sleep, self-care, and quiet activities.77,78 Among pleasurable, productive, and restorative occupations, Howell and Pierce considered restorative occupations as the least recognized.49 Pierce stated,78 “In our clients, the need for improvements in the restorative quality of their occupational patterns can be critical. Without adequate restoration, productivity and pleasure also remain low” (p. 98).

Need to Address Sleep in Occupational Therapy

It is important to consider that a founding figure of the occupational therapy profession, Adolf Meyer, regarded sleep to be one of the four main areas humans need in order to function (in addition to work, rest, and play). It is also noteworthy that the OTPF-2 considers sleep a major human occupation.7 Perhaps an even more compelling reason occupational therapists should address sleep is because it is an occupation in which every human being across the age span engages or should engage. Out of the eight occupational performance areas under the revised OTPF, it is the only performance area that cannot be performed by someone else or by an alternative means. Though the environment and actions surrounding sleep can be adapted, the act of sleeping itself is the only occupational performance area that cannot be adapted for an individual to function optimally, let alone survive.

Dahl bluntly pointed out that “Sleep is not some biological luxury. Sleep is essential for basic survival, occurring in every species of living creature that has ever been studied. Animals deprived of sleep die” (p. 33).28 As this chapter illustrates, sleep and rest, or lack thereof, affects almost every client population with whom occupational therapy practitioners work and within virtually every setting.

Need to Address Rest in Occupational Therapy

As mentioned previously, rest is considered along with sleep to be one of the primary occupational performance areas according to the OTPF-2.7 Rest, however, should not be confused with sleep. According to Dahl,28 “Sleep is not simply rest. Mere rest does not create the restorative state of having slept” (p. 32). Dahl points out that the “fundamental difference between sleep and a deeply relaxed wakefulness is that sleep involves dropping into a state with a relative loss of awareness of and responsiveness to the external world.” If a client such as Mrs. Tanaka “rests” during the day but does not sleep, she will still suffer the loss of sleep with all its unique restorative benefits.

Howell and Pierce discussed the importance of rest in addition to sleep for physical, cognitive, and mental restoration.49 They note the uniqueness of individuals in deciding which occupations are restorative and how one person may consider a particular activity to be relaxing and calming while another may not. The authors also point out that occupations that are highly restorative tend to have strong routines of simple and even repetitive nature, are often considered pleasurable and have personal meaning to the individual based on tradition and history with the occupation.

History of Sleep in Society/Cultural Influences

Howell and Pierce have posited that one of the most significant forces that shape our current view of occupations is the Protestant work ethic,49 which developed during the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s. The values of honesty, thrift, and hard work were developed during this time in Europe when the Protestants separated from the Catholic Church. Leisure was considered a potential temptation into sin.

Coren pointed out that the invention of the light bulb by Thomas Edison served to transform society, making shift work possible throughout the night.26 Prior to the introduction of the modern tungsten filament light bulb in 1913 (an inexpensive and long-lasting bulb), the average person slept 9 hours a night as was documented by a 1910 study.26 The new light bulb served to “free” working people from working in darkness, but, ironically, it may have simultaneously served to decrease the hours of sleep for future generations.

In the 2009 U.S. National Sleep Foundation (NSF) poll,69 1000 telephone interviews were conducted among a random sample of Americans in the continental United States. Respondents were at least 18 years of age and a head of the household. Respondents were asked how many hours of sleep they needed to function at their best during the day. On average, respondents reported needing 7 hours and 24 minutes to function at their best. However, they reported getting an average of 6 hours and 40 minutes of sleep on a typical workday or weekday, almost  hours less than what people reported in 1910. These statistics point to the existence of a culture-wide “sleep debt,” a point of relevance for occupational therapists whose overarching goal is “supporting health and participation in life through engagement in occupations.”7

hours less than what people reported in 1910. These statistics point to the existence of a culture-wide “sleep debt,” a point of relevance for occupational therapists whose overarching goal is “supporting health and participation in life through engagement in occupations.”7

Mrs. Tanaka, whose primary cultural influence is Western, also has beliefs and values about sleep. It is therefore of utmost importance to identify Mrs. Tanaka’s and her family’s beliefs about sleep. Is sleep considered important or a waste of time?

Western Sleep Practices

Sleep behavior among Western industrial societies is distinctive to that culture. In a comparative analysis of sleep amongst industrialized Western society and indigenous cultures, Worthman and Melby pointed out several uniquely Western sleep practices:93

1. Solitary sleep from early infancy, supported by cultural norms and beliefs about risk of overlying need for infant independence of autonomy and need for sexual decorum

2. Consolidation of sleep into a single long bout

3. Distinct bedtimes enforced in childhood and reinforced by highly scheduled daytime hours, for work or school, and mechanized devices for waking

4. Housing design and construction that provide remarkably sequestered, quiet, controlled environments for sleep in visually and acoustically isolated spaces (pp. 104-105)

In contrast, non-Western sleepers habitually engage in co-sleep in shared beds or spaces.93 They also may have a more fluid sleep schedules, more fluid sleep-wake states, and may fall asleep and remain asleep in more sensorially dynamic settings.

Human beings have a tremendous diversity in sleep patterns and sleep developmental histories based on cultural background and upbringing.93 It is important for occupational therapists to be aware of a client’s sleep history and culture so they can set realistic and meaningful goals for them regarding their sleep. The OTPF-2 acknowledges that client engagement in occupations within cultural contexts influence how the occupation is organized.7

It is important for the occupational therapist treating Mrs. Tanaka to find out what her typical sleep habits were prior to the stroke. Did she sleep in her bed alone or with her husband? What time did she normally go to bed and wake up? Did she usually take naps? What habits or routines did she have before going to sleep or upon waking up? Did she experience interruptions during sleep such as getting up to go to the bathroom? What kind of bed did she sleep on? What are her sheet and pillow preferences? Was there noise in the room where she slept? What are comfortable light and temperature levels for her?

Brief History of Sleep Medicine

Sleep medicine as a medical specialty is relatively new. William C. Dement, a pioneer in sleep medicine himself, considers Nathaniel Kleitman, a physiologist who started studying sleep in the 1920s, as the first to devote his professional life to the study of sleep.29,30 Kleitman and Aserinsky first started describing rapid eye movement (REM) sleep in the early 1950s with overnight electroencephalograms (EEG) first being reported in the late 1950s by Dement and Kleitman.31 In 1965, sleep apnea was discovered in Europe,31 and in 1970, Dement founded the first sleep disorders center at Stanford University Hospital. The 1970s saw a proliferation of the opening of sleep disorder clinics. Since that time, sleep medicine has become a specialty in medicine, scholarly journals focusing on sleep were launched, national and international organizations focused on sleep research and education were founded, and a congressional commission focused on sleep was mandated.

Definition of Sleep According to Sleep Medicine

Behavioral Definition: Carskadon and Dement gave a behavioral definition of sleep: “sleep is a reversible behavioral state of perceptual disengagement from and unresponsiveness to the environment” (p. 13).21 Sleep also occurs naturally and periodically.29 Sleep is usually characterized by closed eyes, postural recumbence (lying down), and behavioral quiescence. Other sleep behavior such as sleeptalking and sleepwalking may occur.21

Scientists describe several discrete stages of sleep based on brain wave patterns and eye and muscle activity. The two major types of sleep are non-REM (or quiet) sleep and REM sleep.33 The two states (NREM and REM) exist in virtually all mammals and birds and are as distinct from each other as sleep is from the waking state.21

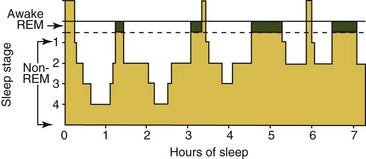

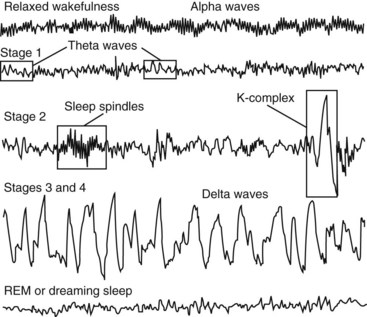

NREM sleep accounts for 75% to 80% of total sleep time in young adults and is usually divided into four stages (S1, S2, S3, S4). The stages are defined by brain wave patterns from an EEG. The EEG pattern in NREM sleep is commonly described as synchronous, with characteristic waveforms such as sleep spindles, K-complexes, and high-voltage slow waves (Figure 13-1).

FIGURE 13-1 Brain waves recorded on an EEG to identify stages of sleep. (From Epstein LJ, Mardon S: Harvard medical school guide to a good night’s sleep, New York, 2007, McGraw Hill.)

Conversely, REM sleep, accounts for approximately 20% to 25% of total sleep time in young adults and is defined by EEG activation, muscle atonia or paralysis, and occasional bursts of rapid eye movements.21 REM sleep is associated with dreaming. This is based on vivid dream recall reported after approximately 80% of arousals from this state of sleep.31 Spinal motor neurons are inhibited by brain stem mechanisms that suppresses postural motor tonus during REM sleep. It is believed that the body is paralyzed during REM sleep to protect dreaming individuals from physically acting out dreams and injuring themselves.

Sleep Architecture

Polysomnography: A polysomnograph (PSG) is a continuous recording of specific physiologic variables during sleep. The PSG is typically performed at night during a sleep study in a sleep clinic. The PSG quantifies sleep and includes an EEG, which measure brain waves, an electromyogram (EMG), which measures muscle activity, and an electrooculogram (EOG), which measures eye movements.95 Young et al. pointed out that a PSG also includes an electrocardiogram (EKG) and measures airflow, oxygen saturation, and body position.95

Epstein and Mardon described how the sleep stages are charted on a diagram (called a hypnogram) made from the data collected from the PSG;33 the chart resembles a city skyline and is referred to as “sleep architecture” by sleep experts (Figure 13-2). A client’s sleep architecture describes the details of an individual’s sleep after an overnight recording of EEG, EOG, and EMG. The hypnogram shows the following:29

Progression of Normal Sleep

Normal young adults first enter sleep through NREM sleep with REM sleep occurring 80 to 100 minutes afterward. Throughout the night in approximately 90-minute periods, cycles of NREM and REM sleep alternate with progressively increasing periods of REM sleep.21 Box 13-1 lists the general stages of sleep with descriptions of bodily functions during the stages.21,33,45,48,83

Sleep across the Age Span

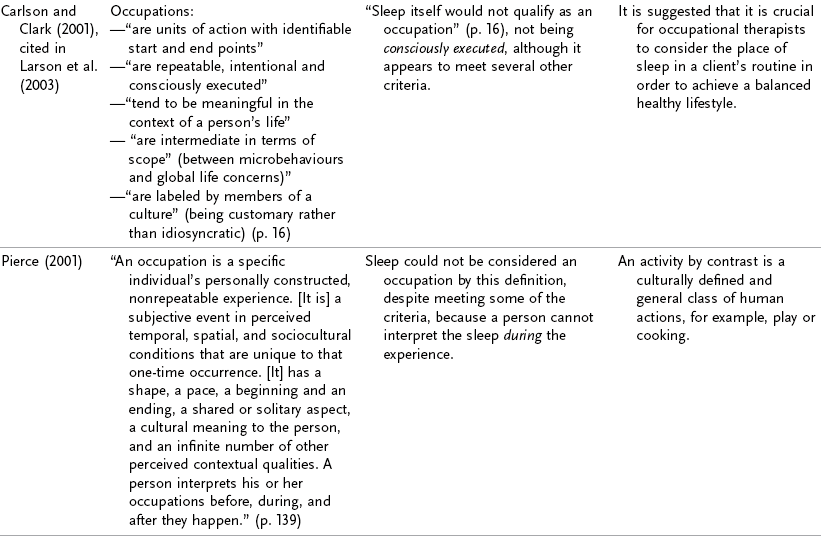

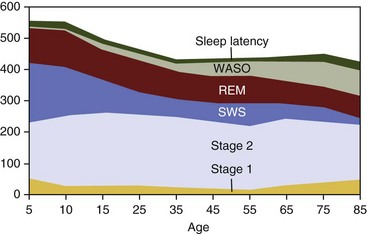

Research shows that age is the strongest and most consistent factor that affects sleep stages (Figure 13-3).21,76 The biggest difference in sleep stages is in newborn infants who enter from wake to sleep through the REM phase for the first year of life. Infants also cycle between REM and NREM, but they cycle through the phases in 50 to 60 minutes instead of the approximately 90 minutes in adults. Deep or slow wave sleep (SWS) is maximized in young children but decreases markedly with age in quantity and quality. For example, children may be very difficult to arouse when they are in deep SWS in the first cycle, whereas an older adult may be easier to awaken in that phase.

FIGURE 13-3 Time is measured in minutes and looks at sleep latency (the time it takes to fall asleep), wake time after sleep onset (WASO), REM, SWS, and stage 1 and stage 2 sleep in terms of age. Note that as we age it takes longer to fall asleep (sleep latency), deep sleep decreases, and stages 1 and 2 increase. Also note that SWS decreases markedly during adolescence. As we age, night awakenings (WASO) also increase. (From Ohayon M, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, et al: Meta analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan, Sleep 27:1255-1273, 2004.)

Adolescence: Although this book focuses on adults, it is felt that a discussion of adolescents is warranted because teenagers (especially older teens) may be treated in traditionally adult settings such as inpatient rehabilitation units, acute care, burn unit, home health, and hand therapy to name a few. Contrary to popular belief, teenagers require more sleep than adults. As cited by Carskadon,20 evidence shows that teenagers need at least 9 to 9.25 hours of sleep a night to maintain optimal alertness.22 Teenagers also have been shown to have a phase delay in the circadian timing system, which means that their biological clocks alert them to stay up late and sleep in later (e.g., sleep from midnight to 9 a.m.).33 These are important considerations to think about in occupational therapy practice in terms of scheduling.

Adulthood: From age 20 to 60, sleep patterns don’t change as rapidly as during childhood. However, there are consistent trends that occur in sleep patterns such as decreased sleep efficiency, decreased time in the restorative deep sleep, as well as easier arousal during the deep sleep phase (Table 13-2). After age 60, the sleep trends of adulthood continue.33 A hallmark of aging is an increased time spent in stage 1 of NREM sleep and a decreased percentage of time in stages 3 and 4, particularly in men. Sleep efficiency also decreases as one ages. Sleep efficiency is measured by dividing the actual time one is asleep by the amount of time one is in bed. Sleep efficiency at approximately age 45 is 86% and declines to 79% for those over 70. Brief arousals are also more common with the elderly. Older adults may also have an advanced sleep phase, meaning that they may get sleepy in the early evening and have a tendency for early morning awakening.

TABLE 13-2

Data from Epstein LJ, Mardon S: Harvard medical school guide to a good night’s sleep (p. 43). New York, 2007, McGraw Hill, p. 43; and Ohayan M, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, et al: Meta analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human life span, Sleep 27:1255-1273, 2004.

Circadian Rhythm and Homeostasis

The timing of human sleep is regulated by two systems in the body: the circadian biological clock and sleep/wake homeostasis.

Circadian rhythms are approximately 24-hour cycles of behavior and physiology that are generated by biological clocks (pacemakers or oscillators).66 The internal biological clock regulates the timing and periods of sleepiness and wakefulness, temperature, blood pressure, and the release of hormones throughout the 24-hour day without need of outside cues for the clock to persist. However, environmental stimuli known as zeitgebers or “time cues” help to synchronize that internal clock to the 24-hour day. Light is the most dominant zeitgeber for most species,66 with bright light having the ability to shift circadian rhythms.14

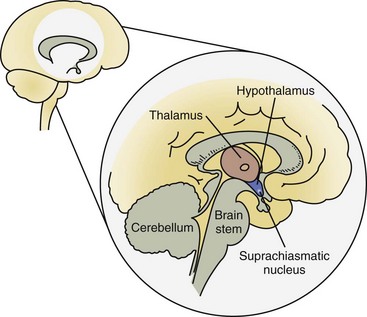

The master circadian (24-hour) clock is located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus of the brain and dictates when we feel sleepy and when we feel most awake. Melatonin, a naturally occurring hormone, is inhibited by light. It is secreted by the pineal gland at night, which induces sleep and has the ability to synchronize circadian rhythms (Figure 13-4).79

FIGURE 13-4 The sleep/wake control center is located in the suprachiasmic nucleus in the hypothalamus. This “pacemaker” regulates the circadian rhythm of sleep and wakefulness. (From Epstein LJ, Mardon S: Harvard medical school guide to a good night’s sleep, New York, 2007, McGraw Hill, p. 21.)

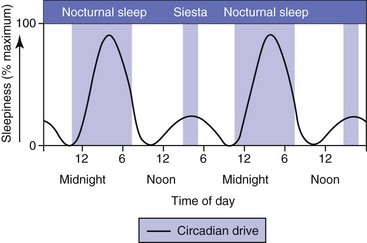

The circadian rhythm for sleep and wakefulness is bimodal, with the strongest desire to sleep between midnight and dawn and in the midafternoon (Figure 13-5).33,67 This explains why people have the most difficult time staying awake between 2 to 4 in the morning and why they feel most sleepy in the afternoon after lunch. If one is sleep deprived, he or she will feel sleepier during those afternoon dips in circadian rhythm than if he or she had sufficient sleep. On the other hand, if one is sleep deprived and has been awake for a long time, he or she may have difficulty falling asleep during those clock “alerting” times. This may explain the quandary of the world traveler who has flown through many time zones and desires to sleep but is unable because his biological clock is telling his body to stay awake.

FIGURE 13-5 The circadian rhythm of sleep and wakefulness has two peaks of sleepiness during the 24-hour day. These peak times of sleepiness are between midnight and dawn (larger peak) and in the afternoon after the typical lunchtime. (From Epstein LJ, Mardon S: Harvard medical school guide to a good night’s sleep, New York, 2007, McGraw Hill, p. 20.)

As cited by Czeisler, Buxton, and Singh Khalsa,27 humans can override the signals of the circadian and sleep-wake system if they have urgent matters to attend to such as studying for a final exam. The invention of artificial light and alarm clock contribute to human need (or desire) to override the biological clock simply because they can or because of societal and cultural pressures to do so.

All phases of normal sleep are considered to be under homeostatic control (homeostasis) or the tendency to maintain equilibrium. The longer one is awake or deprived of certain sleep stages, the greater will be the drive to obtain that lost sleep or stage.88 Stated differently, as soon as one awakens, the sleep debt starts to accumulate. This sleep/wake homeostasis creates a drive that balances sleep and wakefulness.

What Is Considered “Adequate Sleep”?: Determining what is considered adequate sleep varies widely based on age, genetic, and many other factors.21 The National Sleep Foundation recommendations are presented in Table 13-3.

TABLE 13-3

| Age | Sleep Needs |

| Newborns (1-2 months) | 10.5-18 hours |

| Infants (3-11 months) | 9-12 hours during night, and 30-minute to 2-hour naps one to four times a day |

| Toddlers (1-3 years) | 12-14 hours |

| Preschoolers (3-5 years) | 11-13 hours |

| School-aged children (5-12 years) | 10-11 hours |

| Teens (11-17) | 8.5-9.25 hours |

| Adults | 7-9 hours |

| Older adults | 7-9 hours |

From the National Sleep Foundation, www.sleepfoundation.org/article/how-sleep-works/how-much-sleep-do-we-really-need, accessed January 2010.

Sleep Disorders

Many sleep disorders have been researched and identified by sleep medicine researchers. Only the more common sleep disorders are reviewed in the chapter.

Insomnia

In general, insomnia is defined as repeated difficulties with initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, awakening earlier than desired, or having poor quality sleep that is not restorative.32 Insomnia is not considered a disease but is considered a complaint. Insomnia is the most common sleep disorder and in isolation affects 30% to 50% of the general population with 9% to 15% of those reporting impairment in daily activities as a result.32 Risk factors include advancing age, being a female, and having psychiatric or medical problems. The consequence of insomnia is impaired cognition, fatigue or tiredness, depressed mood or irritability, and impaired work or school performance.58 Comorbid insomnia refers to clients who have a medical or psychiatric diagnosis but also have symptoms of insomnia. Box 13-2 lists medical conditions that frequently have comorbid insomnia. These are common medical conditions that occur with symptoms of insomnia.58

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) can be a serious medical condition that is estimated to affect 18 million adults in the United States.33 OSA is twice as common in men than in women prior to age 50 with prevalence in the genders equalizing with age.47 OSA is one of several sleep-related breathing disorders (SRBD) that doctors treat. In OSA the airway becomes blocked when a portion of the individual’s airway slackens, collapses, and closes off the airway blocking airflow. This causes the person to stop breathing then awaken (though not usually fully wake up) throughout the night, sometimes hundreds of times. Apnea is defined as a complete cessation of airflow for a minimum of 10 seconds whether or not there is oxygen desaturation or fragmented sleep. Hypopnea (shallow breathing) is defined as airflow being decreased by 30% or more with oxygen desaturation of 3% to 4%.43 Box 13-3 list symptoms of OSA. This constant awakening throughout the night can lead to severe daytime sleepiness and fatigue. Furthermore, the decrease in oxygen levels throughout the night can cause increase in blood pressure and can lead to cardiovascular disease.33

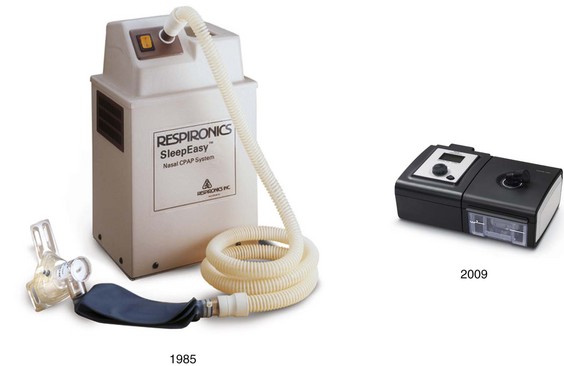

Currently, OSA is typically treated with a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP, pronounced “C-pap”) device (Figure 13-6). The client is fitted with a mask attached to a hose and onto a generator that provides continuous flow of pressurized air through the nose to keep the airway open while the client sleeps. A variety of masks (Figure 13-7) exist, but there are three general types: nasal mask, nasal pillows, and full face mask (Figure 13-8). CPAP has been found to be effective and can be critical to decrease blood pressure in some patients.52 However, up to 50% of clients may be noncompliant.69 Other treatments for OSA include oral appliances or dental devices and surgery.47

FIGURE 13-6 CPAP machines have dramatically decreased in size since they were first introduced. (Images Courtesy of Respironics, Inc. Hayes D Jr., Phillips B: Sleep apnea. In MH Kryger, editor: Atlas of clinical sleep medicine, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.)

FIGURE 13-7 This is a small sample of masks and headgear that are available from several manufacturers. Three general types of masks are used. The two on the right are nasal pillow–type masks where prongs are inserted into the nostrils. In the middle are two full face masks, and to the left are two nasal masks. The bottom nasal mask is for a child. (From Hayes D Jr, Phillips B: Sleep apnea. In Kryger MH, editor: Atlas of clinical sleep medicine, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders Elsevier, p. 190.)

FIGURE 13-8 This man is using a full face mask that fits over both the nose and the mouth and is useful for “mouth breathers” like this client, who needed it to treat severe sleep apnea. (From Hayes D Jr, Phillips B: Sleep apnea. In Kryger MH, editor: Atlas of clinical sleep medicine, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders Elsevier, p. 190.)

If untreated, OSA can have severe adverse effect on a client’s functioning throughout the day. With sleep chronically deprived, daytime function is affected by slowed thought processes, forgetfulness, slowed responses, and difficulty concentrating.90 Clients who have sustained a CVA and have been treated in a hospital rehabilitation program were found to have comorbid SRBD that predicted a poorer outcome on functional recovery rate.23 Researchers suspect that two processes contribute to decreased cognitive functioning in patients with OSA: nocturnal hypoxia (decreased oxygen to the brain) and fragmented sleep. Furthermore, as a group, OSA clients’ risk of motor vehicle accidents is increased twofold. Research has also shown evidence that sleep-disordered breathing precedes stroke and may contribute to the development of stroke.55

Considering the functional and cognitive impairments that can result from OSA, it is important for occupational therapists to query clients about their sleep when evaluating clients who may have a secondary diagnosis of OSA or have symptoms that may indicate an SRBD and referral to a physician. The functional-cognitive impairments may impact client follow-through on home programs, safety, and ability to meet goals, and they can result in decreased quality of life.

Since the mid-1990s it has been known that 60% to 70% of all stroke patients exhibit sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) as defined by an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of 10 episodes per hour.13 Could it be that Mrs. Tanaka has a history of an undiagnosed SRBD? Or is the sleep disturbance the result of the CVA and location of the brain insult? Or is poor sleep hygiene in the hospital the biggest contributor to Mrs. Tanaka’s sleep issues? It is critical for the occupational therapist treating Mrs. Tanaka to keep the physician informed about the client’s sleepiness during treatment and her loud snoring, both of which can be indicators of OSA.

Restless Legs Syndrome

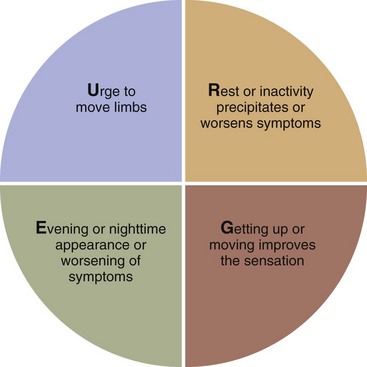

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a common disease that affects a client’s ability to fall asleep and stay asleep.11 RLS affects 10% of adults in the United States with prevalence increasing with age. The four criteria for the diagnosis are the irresistible urge to move the legs due to a creepy crawly sensation when going to sleep, irresistible urge to move the legs, improvement of symptoms with moving legs, and nighttime worsening of symptoms (Figure 13-9).4,11,89

FIGURE 13-9 Essential criteria and core symptoms for RLS. (Cited in Avidon AY: Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements in sleep. In Kryger MH, editor: Atlas of clinical sleep medicine, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders Elsevier, p. 115.)

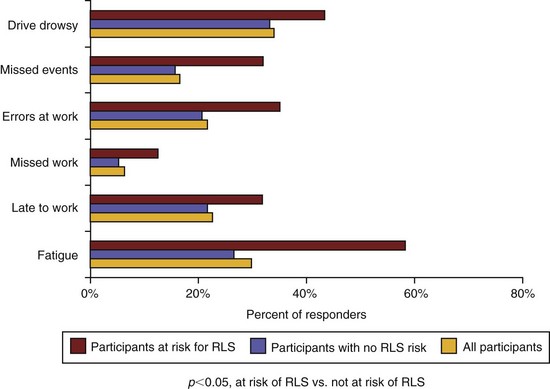

Many clients with comorbid conditions associated with RLS are treated by occupational therapists in inpatient, outpatient, home health, nursing home, and other settings (Figure 13-10). RLS symptoms can occur anytime in the day during prolonged immobilization (e.g., long car drive), but they typically occur in the evening with increasing symptoms until bedtime. The urge to move the legs results in insomnia, effects of which can be detrimental to occupational performance (Figure 13-11).

FIGURE 13-10 Comorbid conditions associated with late-onset (>45 years old), secondary RLS; OTs treat many of these patients in practice. Mg = magnesium, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. (From Avidon A: Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements in sleep. In Kryger MH, editor: Atlas of clinical sleep medicine, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders Elsevier, p. 116.)

FIGURE 13-11 As the figure shows, RLS can have a significant impact on functioning in some daily occupations. (From Avidon A: Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements in sleep. In Kryger MH, editor: Atlas of clinical sleep medicine, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders Elsevier, p. 118.)

It is believed that RLS is related to dopamine deficiency with other hypotheses including brain iron deficiency. Current nonpharmacologic treatment includes encouraging alerting (mentally challenging) activities, which have been found to relieve RLS symptoms, as well as avoidance of caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine.11 With focus on occupation and wellness, these are certainly areas in which occupational therapy practitioners can provide treatment.

Periodic Limb Movement Disorder

Periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) is frequently confused with RLS but is a different condition though they can coexist. PLMD affects up to 34% of patients over 60 years of age with prevalence increasing with age. PLMD can only be definitively diagnosed with an EMG and a sleep study/PSG. In this disorder, a client has periodic episodes of repetitive and stereotyped movements of the limbs (arms or legs), which the client cannot control, during sleep. This results in client arousals or awakenings during sleep, which the client often doesn’t recognize. The “creepy crawly” sensations present in RLS do not exist in PLMD. When this condition is severe, clients experience excessive sleepiness, which can affect daytime functioning.11

Parkinson’s Disease

Sleep problems are common in all forms of Parkinson’s disease (PD).87 The most commonly seen neurodegenerative disorder in a sleep disorders clinic is Parkinson’s disease.12 Of the patients with PD, from 60% to 90% have sleep complaints. A majority of clients with PD have sleep complaints that adversely affect sleep including excessive sleepiness, insomnia, nightmares, and other sleep disorders. As severity of the disease increases, sleep complaints also increase. Improved sleep hygiene is an important treatment that can be provided to this population in addition to training in safe bed mobility and transfer training and provision of adaptive equipment (e.g., bedside commode) for safety in toileting tasks.12

Consequences of Poor Sleep

Sleepiness: The seemingly obvious but not so obvious consequence of sleep debt is sleepiness. Behavioral signs of sleepiness include yawning, ptosis (drooping of the upper eyelid), reduced activity, lapses in attention, and head nodding.81 Besides the embarrassment that may be caused by those behaviors when in a public place, there are serious consequences to sleepiness.

The terms sleepiness, fatigue, and somnolence are sometimes used interchangeably. However, sleepiness should be distinguished from fatigue. Sleepiness is a sleep state that is characterized by the tendency to fall asleep, whereas fatigue is the exhaustion that occurs after exertion.40 Another definition of fatigue, as cited by Bushnik, Englander, and Katznelson,19 is “the awareness of a decreased capacity for physical and/or mental activity due to an imbalance in the availability, utilization and/or restoration of resources needed to perform activity” (p. 46).1 Though many people, including sleep experts, use the word somnolence and sleepiness interchangeably, Gooneratne et al. believe that the terms should not be considered the same.40 Somnolence is an impaired neurologic state that can lead to lethargy or coma, whereas sleepiness is a tendency to fall asleep.

As cited by Roehr et al.,81 sleepiness is a physiologic need state much like hunger or thirst. The body’s desire to sleep cannot be met by resting, eating, taking a cold shower, or exercising. It can only be met by sleep. Researchers have quantified sleepiness by how readily subjects fall asleep, by subjects rating how likely they are to fall asleep in certain situations, and by subjects rating themselves on how they feel at the moment. The Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) is considered the standard method for quantifying sleepiness.81 With this test, subjects are placed in a dark room on a bed. The amount of time it takes the subject to fall asleep is measured every 2 hours during the waking hours on several occasions. Severely sleep deprived individuals fall asleep instantly (zero sleep latency). Generally, many clinicians consider an average latency of 5 to 8 minutes to be consistent with excessive daytime sleepiness; 10 to 12 minutes or more is considered to be within normal limits.24

Research has shown that those who are the most sleep deprived as evidenced by behavioral measures are the least accurate in rating their sleepiness. Roehr et al. have speculated that adaptation to the chronic sleepiness state occurs such that some people actually forget what complete alertness feels like.81 The researchers also reported that for those with mild to moderate sleepiness, subjective complaints of sleepiness and even its behavioral indicators can be masked by a number of factors such as motivation, environment, posture, activity, light, and food intake. The researchers reported: “Heavy meals, warm rooms, boring lectures, and the monotony of long-distance automobile driving unmask physiologic sleepiness when it is present, but they do not cause it” (p. 41). However, for those with significant and severe sleep debt, the ability to override sleepiness diminishes. Even in the most exciting environment, microsleeps can occur as well as likelihood of sleep onset. An example would be a person falling asleep while watching an adventure movie during the most climactic scenes.

A healthy individual becoming sleepy while watching a movie is a relatively benign problem if it is isolated. However, research has found that sleepiness can be a detriment to functioning. One study found that excessive sleepiness in the elderly without dementia or depression was associated with self-reports of moderate impairments in activities such as housework, sports, activities in the morning or evening, and keeping pace with others.40 In this study there were strong associations between those with a number of medical conditions and those reporting excessive sleepiness.

Other studies have shown a relationship that activities and positioning may have an effect on sleepiness. One study showed that sleep latency (how long one takes to fall asleep) increased by 6 minutes when the subject was sitting up rather than lying down. Sleep latency has been shown to also increase by 6 minutes when subjects went for a 5-minute walk prior to taking the MSLT.15,16

Many well-known disasters can be attributed to workers who were sleep deprived, including the Exxon Valdez oil spill (1989), the Three-Mile Island nuclear meltdown (1979), and the Challenger space shuttle explosion (1986).26,29,97

All these findings can have implications for occupational therapists who work with sleepy clients in their goal setting and treatment plans. For Mrs. Tanaka, if medical or psychiatric conditions or medication problems are ruled out, occupational therapists can help ensure the client gets adequate sleep at night. If Mrs. Tanaka’s sleep problem includes a shifted circadian rhythm, light exposure during treatment and between therapies during the day may help to shift her circadian pattern so that she sleeps at night, not during the day. Treatment in an upright posture in a bright room may help to keep her alert longer during treatment so that she can participate in therapy during the day.

Drowsy Driving: Researchers at the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) looked at data during the periods of 1991-2007 on fatal single-vehicle run-off-road crashes. The most influential factor in the occurrence of these fatal crashes was sleepiness. The NHTSA reported that the odds of a sleepy driver being involved in a run-off-road crash are more than three times more likely than they are for a driver who is not sleepy.71 Compared to that, the odds of a driver with alcohol in his system (blood alcohol concentration = 0.01 + grams per deciliter) is almost two times as likely to be in a similar crash than a sober driver. Currently, only the state of New Jersey enacted a Law (Maggie’s Law in 2003) that considers falling asleep at the wheel and fatigued driving a criminal offense in a fatal crash if someone is found to not have slept in 24 consecutive hours.

The National Sleep Foundation has reported the following as the groups most at-risk of being involved in a fall-asleep crash:70

• Young people, especially males under 26

• Shift workers and people with long work hours

• Commercial drivers, especially long-haul drivers

• People with undiagnosed or untreated disorders (those with untreated OSA have been shown to have up to seven times increased risk of falling asleep at the wheel)

Shift Work: Research that shift work can be deleterious to your health is well documented. As previously mentioned, the invention of artificial light and the Industrial Revolution changed the work world so that people can now work around the clock. The prevalence of shift work sleep disorder that results in insomnia is estimated to be about 10% of the night and rotating shift worker population.80

Neuromuscular Disorders and Sleep

Individuals with neuromuscular disorders are considered in a “state of vulnerability” during sleep, as normal REM-related changes such as atonia and other changes in ventilation are magnified as a result of muscle weakness. Sleep disturbance can also be related to spasticity, poor secretion clearance, sphincter dysfunction, inability to turn, pain, and any associated or secondary autonomic dysfunction. All these factors can impair sleep and decrease daytime functioning.39 Individuals who rely on accessory muscles to breathe (e.g., tetraplegia) are also in a vulnerable state during sleep. Sleep disturbance is also a common consequence of traumatic brain injury (TBI), and those with this condition constitute another population of clients that occupational therapists treat.74

Other Consequences of Sleep Deprivation: As cited in Young et al.,95 sleep deprivation can result in a multitude of negative physical and psychological consequences even when the person is healthy. These negative consequences include but are not limited to hypertension,37,75 decreased postural control,34 and possible obesity and diabetes.38,57 Inadequate sleep can also result in greater likelihood of falls.84 In older adults, the consequences of poor sleep are significant and can result in overall poorer health, physical function, cognitive function, and increased mortality.9

Sleep Considerations in the Hospital Setting: As mentioned previously, inadequate sleep can have serious consequences in and of itself. Acute hospitalization combined with inadequate sleep can further hinder recovery. Studies have shown that approximately half of patients admitted to general medical wards complain of sleep disruption. Young et al. have suggested that patients who are hospitalized have difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep and complain of early awakening and nonrestorative sleep.95 Hardin reported that for more than 30 years sleep abnormalities have been documented in patients who are hospitalized in the intensive care unit (ICU).45 Environmental noises and patient care activities account for about 30% of awakenings in ICU patients.36 The noise levels in ICUs are found to be especially high.65 However, nursing care activities such as taking vital signs and giving sponge baths may actually contribute more to the patient awakening than do the environmental conditions.35

The etiology of sleep disturbances in the hospital or institutional setting are multifactorial and can be related to a patient’s medical illness, medical treatments, and environment.95 Patients treated in a traditional rehabilitation setting may also have a higher likelihood of sleep disturbance. One study indicated that of 31 consecutive admissions to a brain injury unit with a diagnosis of closed head injury (CHI), 68% were shown to have sleep-wake cycle disturbance.59 Those with the aberrations in nighttime sleep had longer stays in both the acute and rehabilitation settings, important to consider with concerns over high healthcare costs.

Taking account of these factors, it is important to consider Mrs. Tanaka’s sleep patterns at the facility or unit prior to admission to the rehabilitation hospital or unit. Was Mrs. Tanaka in the ICU? How long was she there prior to admission to the rehabilitation unit? Was her sleep disturbed in that setting?

To Nap or Not to Nap?

The research has been mixed on whether it’s a good idea for one to nap during the day. The primary concerns are that napping fragments sleep and that consolidated nighttime sleep may be disrupted as a result. One study suggested that sleep disruption is common and severe among older persons receiving inpatient postacute rehabilitation and that excessive daytime napping was associated with less functional recovery for up to 3 months after admission.2 However, other researchers are finding benefits to napping and recommend short naps as we age to accommodate the normal age-related changes to sleep (Box 13-4).46

Nocturia

Nocturia is defined as waking one or more times to void (urinate) at night and is the most common lower urinary tract symptom.17 As Booth and McMillan have cited,17 prevalence studies indicate that nocturia increases in both genders with age.50,82 The most significant consequence of nocturia is sleep disturbance with evidence of fatigue during the day impacting energy and activity.10 Research shows that there is an association between risk of falls and nocturia and that caregivers and other sleeping partners are also at risk of falls during the night and day because of fatigue due to sleep disruption.10 When evaluating clients on their ADL status, occupational therapists should always ask clients about their voiding habits at night. Frequency of voiding can alert the occupational therapy practitioner to sleep disturbances and help to determine safe toileting equipment, routines, splint schedules, safe environmental setup, and need for referral to the client’s physician.

Occupational Therapy and Sleep

In current practice, a sleep disturbance may not be the primary reason a client is seeking services from occupational therapy. However, because it is established that insufficient sleep can negatively impair all occupations, it is clearly an important area to consider in occupational therapy treatment in all practice settings. Based on estimates from a 2006 survey from state occupational therapy regulatory boards, AOTA staff estimate that there are roughly 118,500 occupational therapy practitioners in the workforce in the United States.6 Occupational therapy practitioners in all practice settings being well versed on the topic of sleep and rest can have a significant positive impact on society.

Occupational Therapy Evaluation

It is important to obtain a thorough occupational profile of the client during the evaluation. This includes the client’s history and experiences, patterns, interests, values, and needs.7 Included in the profile should be questions regarding the client’s sleep and rest patterns, routines, and habits. A thorough medical history and information on whether the client has a history of sleep disorders or difficulties should be included.

Occupational Therapy Intervention for Sleep and Rest

According to the OTPF-2,7 the types of occupational therapy intervention include therapeutic use of self, therapeutic use of occupations and activities, consultation, education, and advocacy. All of these interventions can be used when treating patients regarding the occupations of sleep and rest.

Therapeutic Use of Self

The occupational therapy practitioner can demonstrate caring and concern for the client or caregivers regarding the amount and quality of rest and sleep they are obtaining. Sleep medicine is a relatively new discipline, so many doctors do not ask their patients about their sleep or don’t recognize the signs of sleep disorders or issues.33 The occupational therapy practitioner may be the first to ask a client/caregiver of sleep concerns because of occupational therapy’s attention to occupations, routines, and life balance.

The occupational therapy practitioner can practice “mindful empathy,” which is an objective mode of observation of the client’s emotions, needs, and motives while being objective.85 Instead of judging a client for canceling appointments or not fully participating in treatment, actively listening to a client and reassessment of the situation could reveal a sleep-deprived client.

Therapeutic use of self also includes occupational therapy practitioners being more knowledgeable and having competency in the areas of sleep and rest to help clients to optimize their sleep and rest patterns. Becoming knowledgeable about sleep and sleep disorders can help the occupational therapy practitioner to recognize any problems that may indicate severe sleep disturbance so the client can be referred to a doctor or sleep specialist.

Occupational therapy practitioners can also model good sleep practices so they are alert, safe, and functioning at their best when working with clients. Occupational therapy practitioners need to examine their own values about sleep and rest. Is sleep and rest considered a waste of time? Is someone lazy if they require a nap during the afternoon?

Developing cultural competency is a “central skill” for using oneself therapeutically.89 As previously mentioned, recognizing and appreciating diversity in sleep and rest is important as definitions, patterns, practices, and environments may completely differ from our own. Mrs. Tanaka’s views and experiences with sleep, habits, and patterns of sleep are all important considerations when treating her. For example, if Mrs. Tanaka’s family reports she always used a night light to sleep and was afraid of the dark, we should not impose complete darkness in her room at night as a sleep hygiene technique.

Therapeutic Use of Occupations and Activities

The therapeutic occupations and activities can focus on helping the client to have a healthy lifestyle balance and routines to ensure adequate rest and sleep. An activity configuration or pie chart can be used with the client to review occupations that are important to the client and to assess how time is spent and the portion of time allocated to each of these occupations.

Schedules: Consider optimal times for activities of daily living (ADLs) training (e.g., if client is a “night owl,” don’t schedule shower/dressing training at 7 a.m.). Try to schedule certain ADLs at “customary” times, especially for clients with cognitive impairment (e.g., working on dressing in the a.m. instead of at 1:30 in the afternoon) so that they become accustomed to a routine. Consult with other team members or family members and ensure that clients are getting sleep and rest. Keep track of sleep by using a sleep chart or diary. Schedule in regular daytime naps in bed (if possible; not in a wheelchair or recliner) or rest breaks if needed. Keep the medical team informed about client’s alertness during therapies.

Dressing: If dressing is considered a usual habit for a client, dissuade the use of pajamas during the day and have clients dress in “street” clothes during the day. Encourage pajamas or “usual” sleeping clothes at night while on a rehabilitation unit or when recovering from illness or injury at home. However, it is important to note that some clients regularly wear housecoats during the day. Some cultures may also deem it necessary to wear pajamas because the client is still considered “sick.”

Hygiene and Grooming: If a client normally shaves or wears makeup during the day, encourage this as part of the morning/daytime routine if it’s important to the client. Ensure that the client and caregiver have a routine for activities to get ready for the day and to go to sleep at night.

Bed Positioning/Bed Mobility/Bed/Bedding: Train the client and caregiver(s) in bed positioning to ensure comfort and optimal functioning. Are there enough pillows? Does the head of bed need to be elevated? Does an extremity need to be elevated? Are there other precautions that need to be followed while the client is in bed (total hip, logroll, etc.)? Train the client and caregivers in bed mobility techniques for safety. Assist in determining the optimal bed for the client to use to facilitate sleep with consideration for skin protection, breathing, and mobility/transfer status at the forefront. Ensure that the client has easy access to call light, and make or request adaptations to the call light if needed. If the client is going to be away from home, consider if a special quilt or blanket from home may assist the client to sleep or whether particular textures for sheets may be more suitable for the client to use during sleep for skin protection or comfort.

Environment: To encourage sleep, turn lights off, encourage a quiet room, turn the TV off, and close the door fully if needed and if safe. Consider whether client gets overstimulated with too many items posted on the wall. Make sure the floor is clear of clutter and obstructions for safety. Remove throw rugs. Make sure the temperature in the room is comfortable for the client to sleep. Extra blankets may be needed for those clients who tend to get cold.

Transfers: Train client, caregivers, and family members in safe transfer techniques onto commode or other transfers that may occur at night.

Toileting: Consider the most appropriate times for catheterization, voiding, and bowel program to optimize rest and sleep. Ensure that any equipment (commode, urinal, etc.) is readily available by the bedside. Discuss with medical team, client, and caregivers optimal toileting techniques to encourage sleep at night for all concerned and for safety (e.g., with approval by the physician, for males, initial use of condom catheter at night for urination versus use of commode if transfers are difficult).

Showering/Bathing: Consider the most optimal time for a bath or shower to encourage sleep at night or wakefulness during the day to participate in therapies or daytime activities. Perhaps a morning shower would “wake up” a client in the morning. Consider that optimal times for client to take shower or to bathe may be at night to help with sleep. Safety should be the highest consideration when determining showering/bathing times.

Eating/Meals: Work on feeding activities and encourage meals out of bed with the rest of the family in the family dining area, as appropriate, to ensure that daily rhythms are reinstated to help distinguish day from night.

Home Safety Evaluation: As appropriate, perform a home evaluation to ensure that the home is safe for transfers, toileting, ambulation at night, and to determine any equipment needs. Suggestions can be made for bed placement, and night lights and call bells can be set up as needed. Confer with a physical therapist about optimal ambulation devices.

Other Activities: Try to schedule treatments outdoors so that the client is exposed to light as it is the strongest zeitgeber and can help to reset the biological clock if it is off kilter. Collaborate with the client and family to make sure activities selected are interesting and important for the client. Clients sometimes sleep during the day because they’re bored. Encourage participation in activity groups, therapeutic recreation groups, and community events if it helps the client to sleep at night. Make suggestions for and encourage quiet restful evening activities. As mentioned previously, Howell and Pierce have pointed out that occupations that are highly restorative tend to have strong routines of simple and repetitive nature, are often considered pleasurable, and have personal meaning to the individual.49 West has suggested relaxing activities such as reading, stretching, meditating, or praying before bedtime.91 Use of sleep preparatory activities such as visual imagery and massage can also be used.91 Some evidence suggests that aromatherapy with essential oils such as lavender and chamomile may have some promise in helping to induce a state of mind that assists with sleep.92 However, continued research is needed to find evidence of its effects on sleep architecture by polysomnography.92

Community Mobility: Occupational therapy practitioners can train clients who are no longer deemed safe to drive because of sleep disorders in community mobility and alternative transit (see Chapter 11, Section III).

Splint/Exercise Schedule/Pain: Consider client sleep when giving splinting schedule instructions. Ensure proper fit for comfort so that client can sleep. Make sure the splint schedule doesn’t interfere with sleep or that the continuous passive motion (CPM) machine, typically used with clients who require a total knee replacement, doesn’t keep the client awake all night. Collaborate with physical therapy about CPM use. Make sure exercises are performed at a time that will optimize sleep at night. Consider client pain levels and consult with medical staff and doctors. Talk to the client about whether he or she is unable to sleep at night because of pain.

Cognitive Strategies: Develop cognitive strategies to help manage negative, anxiety-producing thoughts and concerns.56 Examples of negative, anxiety-producing thoughts are “I’ll never sleep again” or “It’s already 2 o’clock in the morning, and I have to wake up in four hours.” Occupational therapists can consider training in cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). Cognitive behavioral therapy usually focuses on modifying unhealthy sleep habits, decreasing autonomic and cognitive arousals, altering dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep, and educating clients about healthier sleep hygiene practices. Research has supported the use of CBT as a nonpharmacologic treatment to sleep disturbance.51

Consultation

Occupational therapists can provide consultation in institutional settings where a 24-hour “on” schedule is frequently in place. Consult with the treatment team and staff about providing an optimal sleep environment for clients at night. Discuss with team the necessity for middle-of-the-night nonurgent blood pressure readings, sponge baths, and blood draws, and recommend they be avoided. Provide training to night-shift aides, nurses, orderlies, and caregivers in bed mobility, bed positioning, transfer techniques, and body mechanics.

The occupational therapist can act as a consultant in worksite settings and can meet with managers and administrators about the importance of sleep for optimal functioning and safety. Encourage balance in life for a more productive and safe workforce. West pointed out that consultation services may be particularly useful in settings that employ shift workers (e.g., hospitals, factories, airlines), providers of driver education, the military, and emergency relief programs.91

Certified rehab driving specialists who are occupational therapists can educate clients and the public at large about the dangers of drowsy driving (see Chapter 11, Section III). These occupational therapists who are specialists in adaptive driving and evaluation for disabled or at-risk individuals are usually the most up to date about regulations and information regarding driving, and they can act as consultants to other occupational therapy practitioners and healthcare professionals.

Education

In an institutional setting, the occupational therapist can educate and empower the client and family to have a strict visitation schedule if needed and dissuade “too many” visitors at night or during scheduled rest times, which may interrupt rest and sleep when one is in an acute hospital setting. Occupational therapy practitioners can help empower caregivers to limit visits to short periods of time or help with the enforcement of visitation rules. The occupational therapist can educate caregivers about sleep and make sure they realize how important it is for them to get their own rest and sleep.

Some institutions require doors in rooms to be open at night despite the lights and noise. Education can be provided to staff about how best to facilitate sleep in these settings. Young et al. suggested several strategies,96 including offering earplugs and eye masks, encouraging regular nocturnal sleep time, and discouraging long daytime naps. Other suggestions include encouraging the medical staff to minimize nighttime bathing, dressing changes of wounds, or other medical procedures and to avoid discussing emotionally charged topics with the patient at night.

Occupational therapy school educators can inform their college students—who are known to be at risk for erratic sleep behaviors and significant sleep debt—about the consequences of sleep deprivation. If afternoon classes are scheduled, more “active” class activities may be required to fend off sleepiness for the instructors and students during the circadian clock’s “sleepiness” times. Occupational therapy and occupational science educators can coordinate assignment due dates and spread them out to encourage balance for the instructor and students and to ensure proper sleep for both.

As cited by Green, Hicks, and Wilson,42 patients complain of the lack of information about the management of insomnia.72 Occupational therapists can provide education to the sleep-deprived public in community practice settings.

Sleep Hygiene

Sleep hygiene refers to activities involving lifestyle choices and environmental factors that can lead to healthy sleep. Sleep specialists provide sleep hygiene education with the intent to provide information about lifestyle and environments that either interfere or promote sleep.68 Occupational therapy practitioners can also provide sleep hygiene information to support healthy active engagement in other areas of occupation.7

In its description of sleep as an occupation, the OTPF-2 describes sleep hygiene activities thusly: “A series of activities resulting in going to sleep, staying asleep, and ensuring health and safety through participation in sleep involving engagement with the physical and social environments” (p. 632)7 (Box 13-5).

Recommendations for Sleep Hygiene:

• Develop a regular sleep-wake cycle. Use an alarm clock if needed.

• Develop a relaxing routine before bedtime.

• Prepare a quiet environment for sleep or use “white noise” to foster sleep.

• Avoid mentally stimulating or arousing activities before bedtime.56

• Remember that the only activities that should occur in bed are sleep and sex (avoid reading, watching TV, texting, tweeting, or using other media/computer devices in bed).

• Do not use alcohol to fall asleep. Alcohol can make snoring and OSA worse. Evidence exists that three to five glasses of alcohol in the evening can cause arousal when the effects of the alcohol wear off.29

• Do not use caffeine prior to sleep. Caffeine has a half-life of 3.5 to 5 hours depending on one’s age, activity, or body chemistry, which means that it could be in your body for many hours after ingesting it.29,63

• Avoid medicines that will keep one awake at night. Confer with a doctor about medications taken at night, particularly those affecting sleep occupations (no diuretics at night, etc.).95

• If one can’t fall asleep in a reasonable amount of time (e.g., 15 minutes) while in bed, leave the bed, go to another room, or perform another activity until one feels sleepy.

Determining When to Refer to a Physician/Sleep Specialist

Refer the client to a physician or sleep specialist if he or she complains of any of the following conditions:33

• Has trouble initiating sleep or getting restful sleep for more than a month or two

• Does not feel rested despite getting the usual amount of sleep or more sleep than he or she is accustomed to getting in order to feel rested

• Falls asleep at inappropriate times, even though he or she is getting  to 8 hours of sleep

to 8 hours of sleep

• Is told he or she snores loudly or gasps and has periods of not breathing that disrupts a bed partner or roommate

• Has to sleep in a different room because a bed partner claims the client’s snoring is too disruptive

• Follows good sleep hygiene habits but still has difficulty sleeping

Other reasons to refer a client to a physician or sleep specialist:

• Caregivers complain that the client is awake all night and sleeps all day.

• A cognitively impaired client is not able to report clearly his or her sleep habits but has obviously declined in occupational performance areas (ADLs, mobility, etc.) and you suspect poor sleep.

• The client falls asleep regularly during your treatment in the daytime.

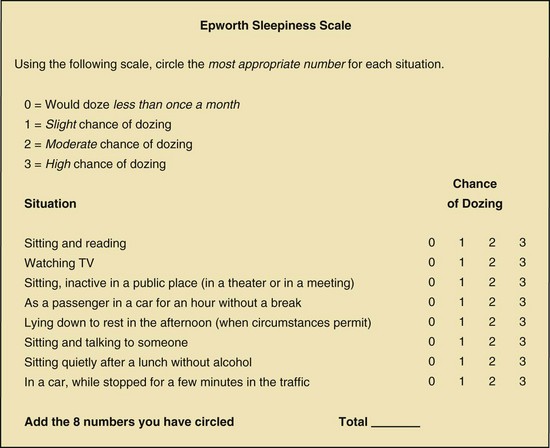

If appropriate, have the client fill out a sleepiness scale such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, which was validated in clinical settings (Figure 13-12).53 A total of 10 or more indicates excessive daytime sleepiness. A score of 6 is the norm.97 Present the data to the client’s doctor. Notify the physician of the client’s deficits in occupational performance or other symptoms resulting from sleep deprivation.

FIGURE 13-12 The Epworth Sleepiness Scale was validated in clinical settings and can be used by occupational therapists to collect information to refer a client to a physician. A total of 10 or more indicates excessive daytime sleepiness. A score of 6 is the norm. However, clients with insomnia can have scores in the normal range. A score of 12 to 24 may indicate a severe abnormality. (Adapted from Johns MW: A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth Sleepiness Scale, Sleep 14(6):540-545. Zupancic M, Swanson L, Arnedt T, and Chevrin R. Impact, presentation and diagnosis. In MH Kryger, editor: Atlas of clinical sleep medicine, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.)

Summary

Historically, occupational therapists and occupational scientists have been interested in the importance of helping clients to maintain a healthy balanced lifestyle.25 Included in that balance should be adequate sleep and rest, two “restorative” occupations.78 According to the second edition of the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework,7 the category of sleep and rest is considered a major occupational performance area that is in the domain of occupational therapy practice; accordingly, addressing this area in all practice settings is appropriate.

Occupational therapists have not traditionally treated clients whose diagnosis or problem has been primarily sleep disorders. However, the sleep medicine literature abounds with information about the deleterious effects of sleep deprivation, including the effects on the at-risk clients whom occupational therapists treat on a daily basis in physical disability and other practice settings. Although occupational therapy has not focused research on rest and sleep, sleep medicine research affirms what occupational therapy practitioners have known all along. Humans need to sleep. Humans need to rest. Otherwise, occupational performance declines and can negatively affect one’s quality of life and health. However, compelling evidence suggests that occupational therapists could and should put more emphasis, research, and practice in helping clients who have sleep difficulties.

Reflecting on the case of Mrs. Tanaka, it is evident that occupational therapy practitioners can help make a positive difference in her rehabilitation outcomes by focusing on her sleep disturbance once medical issues have been ruled out. A multitude of reasons may explain Mrs. Tanaka’s sleep disturbance. The exact location of her brain injury event may help the medical team determine if the disturbance is organic. The occupational therapist who is educated and attuned to the sleep and rest needs of Mrs. Tanaka can—through the therapeutic use of self; the therapeutic use of occupations; and activities, consultation, education, and advocacy—help the client to successfully reach her rehabilitation goals.

1. What is sleep architecture?

2. Does sleep architecture change as we age?

3. What is REM sleep, and how does it differ from NREM sleep?

4. Why should occupational therapy practitioners address sleep in their practice?

5. What is the difference between sleep and rest?

6. Where does the area of sleep and rest fit into the second edition of the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework?

8. What is the Multiple Sleep Latency Test? What is the Epworth Sleepiness scale?

9. When is it appropriate to refer a client to a physician or sleep specialist?

10. How can an occupational therapist help to improve a client’s sleep hygiene in a hospital setting?

11. Name at least five consequences of inadequate sleep.

12. What is obstructive sleep apnea, and what are some signs and symptoms of the disorder?

References

1. Aaronson, LS, Teel, CS, Cassmeyer, V, et al. Defining and measuring fatigue. J Nurs Scholarsh. 1999;31:45–50.

2. Alessi, CA, Martin, JL, Webber, AP, et al. More daytime sleeping predicts less functional recover among older people undergoing inpatient post-acute rehabilitation. Sleep. 2008;31(9):1291–1300.

3. Allen, C, Glasziou, P, Del Mar, C. How helpful is bed rest? www.findarticles.com/cf_1/moBUY/2_10/62276761/print.jhtml, 2000. [retrieved February 19, 2001, from].

4. Allen, RP, Picchietti, D, Hening, WA, et al. Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology: a report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4(2):101–119.

5. American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process. Am J Occup Ther. 2002;56(6):609–639.

6. American Occupational Therapy Association. Workforce trends in occupational therapy. Bethesda, MD www.aota.org/Students/Prospective/Outlook/38231.aspx, 2006. [retrieved February 10, 2010].

7. American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process, ed 2. Am J Occup Ther. 2008;62(6):625–683.

8. American Occupational Therapy Association. Blueprint for entry level education. Am J Occup Ther. 2010;64(1):186–201.

9. Ancoli-Israel, S. Sleep and its disorders in aging populations. Sleep Med. 2009;10:S7–S11.

10. Asplund, R. Nocturia: consequences for sleep and daytime activities and associated risks. Eur Urol Suppl. 2005;3(6):24–32.

11. Avidon, AY. Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements in sleep. In: Kryger MH, ed. Atlas of clinical sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:115–124.

12. Avidon, AY. Sleep in Parkinson’s disease. In: Kryger MH, ed. Atlas of clinical sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:131–134.

13. Bassetti, C, Aldrich, M, Chervin, R, Quint, D. Sleep apnea in the acute phase of TIA and stroke. Neurology. 1996;47:1167–1173.

14. Bonnet, MH. Acute sleep deprivation. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, eds. Principles and practice of sleep medicine. ed 4. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2004:51–66.

15. Bonnet, MH, Arand, DL. Arousal components which differentiate the MWT from the MSLT. Sleep. 2001;24:441–447.

16. Bonnet, MH, Arand, DL. Sleepiness as measured by the MSLT varies as a function of preceding activity. Sleep. 1998;21:477–484.

17. Booth, J, McMillan, L. The impact of nocturia on older people: implications for nursing practice. Br J Nurs. 2009;18(10):592–596.

18. Browse, NL. The physiology and pathology of bed rest. Springfield, IL: Thomas; 1965.

19. Bushnik, T, Englander, J, Katznelson, L. Fatigue after TBI: association with neuroendocrine abnormalities. Brain Inj. 2007;21(6):559–566.

20. Carskadon, MA. Factors influencing sleep patterns of adolescents. In: Carskadon MA, ed. Adolescent sleep patterns: biological, social, and psychological influences. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2002:4–26.

21. Carskadon, MA, Dement, WC. Normal human sleep: An overview. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, eds. Principles and practice of sleep medicine. ed 4. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2004:13–23.

22. Carskadon, M, Orav, EJ, Dement, WC. Evolution of sleep and daytime sleepiness in adolescents. In: Guilleminault C, Lugaresi E, eds. Sleep/wake disorders: natural history, epidemiology, and long-term evolution. New York: Raven Press; 1983:201–216.

23. Cherkassky, T, Oksenberg, A, Froom, P, King, H. Sleep-related breathing disorders and rehabilitation outcome of stroke patients: a prospective study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;82(6):452–455.

24. Chervin, RD. Use of clinical tools and tests in sleep medicine. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, eds. Principles and practice of sleep medicine. ed 4. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2004:602–614.

25. Christiansen, CH, Matuska, KM. Lifestyle balance: a review of concepts and research. J Occupational Sci. 2006;13(1):49–61.

26. Coren, S. Sleep thieves: an eye opening exploration into the science and mysteries of sleep. New York: The Free Press; 1996.