Work Evaluation and Work Programs

History of occupational therapy involvement in work programs

Role of the occupational therapist in work programs

Functional capacity evaluation

Work hardening/work conditioning

Empowering corporate clients: the injury prevention team

Training in risk factor identification/ergonomic evaluation and problem solving

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

1 Understand the role of occupational therapy in the development of work programs.

2 Describe the different types of work evaluation and work programs that are currently being practiced.

3 Identify the components of an industrial rehabilitation program.

4 Understand the difference between work hardening and work conditioning.

5 Identify the aspects of a well-designed functional capacity evaluation.

6 Explain the importance of reliability and validity in the context of evaluation.

7 Understand the differences between job demands analysis, ergonomic evaluation/hazard identification, and worksite evaluation.

8 Discuss the application of job demands analysis.

9 Discuss basic ergonomic interventions.

10 Describe the components of injury prevention programs.

11 Describe school-to-work transition services.

History of Occupational Therapy Involvement in Work Programs

The therapeutic use of work has always been a core tenet of occupational therapy since the inception of the profession.32 Work programs have their roots in those with mental illness during the moral treatment movement, which started in Europe in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.77 In 1801, Philippe Pinel, one of the founders of moral treatment, first introduced work treatment in the Bicentre Asylum for the Insane. He suggested that “prescribed physical exercises and manual occupations should be employed in all mental hospitals. … Rigorously executed manual labor is the best method of securing good morale. … The return of convalescent patients to their previous interests, to industriousness and perseverance have always been for me the best omen of a final recovery.”80 Later in the 1800s, several psychiatric settings instituted productive activity programs.

In 1914, George Barton, one of the founding fathers of the occupational therapy profession who was disabled by tuberculosis and a foot amputation, established the Consolation House in New York.89 This program enabled convalescents to use occupations to return to productive living.89 Barton stated, “the purpose of work was to divert the mind, exercise the body, and relieve the monotony and boredom of illness.”83

In 1915, Eleanor Clarke Slagle, another founder of the occupational therapy profession, was hired to create a program for persons with mental or physical disabilities to work and become self-sufficient.89 The program was located at Hull House, a settlement house in Chicago, and was funded by philanthropic contributions. The participants involved in the program produced goods such as baskets, needlework, toys, rugs, and cabinets while developing manual skills and receiving wages for their work.

The early leaders of occupational therapy identified the importance of work when defining the profession’s focus and purpose. Adolph Meyer, a psychiatrist who emigrated from Germany at the time and was an early proponent of moral treatment, observed that healthy living involved a “blending of work and pleasure.”61 Dr. Herbert Hall helped establish a medical workshop at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, where clients were involved in “work cure.”30 In this workshop, clients produced marketable goods and received a share of the profits. The focus of treatment in these curative workshops was to restore the impaired body part to as normal function as possible, with the goal of returning the client to work.

While this curative workshop movement was transpiring on the East Coast, similar programs were developing elsewhere in the United States. For example, at the Los Angeles County Poor Farm, now recognized as Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center in Downey, California, “all inmates were requested to do an amount of work that was commensurate with their physical strength and mental capacity, which was determined by the admitting doctor.”27 Inmates used woodworking machinery to build a large amount of furniture that was used at the farm. Commodes, bedside tables, wheelchair tables, park benches, cabinets, and other items were built in the shops. In later years when there was a true occupational therapy department, patients made Navajo-type rugs, rag or braided rugs, brushes, shawls, pottery, pictures, baskets, and leatherwork (Figure 14-1, A). Patients took special occupational therapy classes “which were designed to enable those who are crippled, blinded or otherwise handicapped to make themselves useful” by producing articles that could be used at the County Farm or sold to employees or the California Crafts and Industries Society in Los Angeles (Figure 14-1, B).27

FIGURE 14-1 A, Patients at work weaving rugs in the occupational therapy shop at the Los Angeles (LA) County Poor Farm. B, Patients with a display of their products made at the LA County Poor Farm. (From Fliedner CA: Occupational therapy: for the body and the mind. In Rodgers GM, editor: Centennial Rancho Los Amigos Medical Center 1888-1988, Downey, Calif, 1990, Rancho Los Amigos Medical Center.)

In the early 1900s, the medical profession did not seem to consider vocational readiness programs to be important. The focus of care for persons with physical illnesses was primarily palliative and involved immobilization and bed rest. This attitude shifted after World War I with the need to rehabilitate the large numbers of injured soldiers to help them become functional and gain employment.

The U.S. Federal Board for Vocational Education (FBVE) was created after adoption of the Vocational Education Act of 1917.42 In 1918, the Division of Orthopaedic Surgery in the Medical Department of the Army organized a reconstruction program for disabled soldiers.77 One of the founders of occupational therapy, Thomas Kidner, served as an advisor. This program led to the development of reconstruction aides, who were the precursors to occupational and physical therapists. Treatment involved both handicrafts and vocational education. The reconstruction aides used work activities to return the injured soldiers to military duty or civilian life to the highest degree possible.

In 1920, Congress passed the Civilian Rehabilitation Act of 1920 (Smith-Fess Act, Public Law 66-236). This law provided funds for vocational guidance and training, work adjustment, prostheses, and placement services.42 If therapy was part of a medical treatment program, the law provided payment for occupational therapy services; however, it did not provide payment for physician services. Physicians either provided free services or received payment through state or volunteer contributions. This limited the use of occupational therapy services in vocational rehabilitation to the states that supplemented federal program funds to support services such as the curative workshops.

The Social Security Act of 1935 defined rehabilitation as “the rendering of a person disabled fit to engage in a remunerative occupation.”53 This was the first attempt to provide vocational rehabilitation to the physically handicapped in the community.

In 1937, industrial therapy, called employment therapy, was born.58 The occupational therapist used activities as treatment modalities. It was common for patients to have work assignments in the hospital that matched their experience, aptitude, and interest. Sheltered work environments within the hospital were used, including the hospital laundry, barber shop, and carpenter shop.

The term prevocational started appearing in the literature by the late 1930s. It referred to the use of crafts to develop skills readily transferable to industry.101 Prevocational therapy prepared patients for the work role. Occupational therapists worked as directors, work evaluators, and prevocational therapists in work programs. In the 1940s, prevocational programs and work evaluation were accepted as part of the practice of occupational therapy. Patients in acute care facilities who were physically disabled were transferred to outpatient or rehabilitation prevocational and vocational programs.

World War II brought more opportunities for occupational therapists to become involved in work programs. With the advancement of medicine and pharmacology, many injured soldiers survived their wounds. Federal funding for rehabilitating disabled veterans increased as the government discharged the disabled soldiers. This led to an increase in the development of work programs designed to evaluate and rehabilitate injured veterans.17

In 1943, the Barden-LaFollette Act (Public Law 78-113) modified the original provisions of the Civilian Rehabilitation Act of 1920.42 This new law, called the Vocational Rehabilitation Act, covered many medical services, including occupational therapy and vocational guidance. Services were expanded to those with physical and mental limitations. This law also created the Office of Vocational Rehabilitation, a state and federally funded agency that is still in existence today and provides job training and placement services to people with disabilities. Industrial therapy continued in various settings as a form of vocational rehabilitation.

During the 1950s, many occupational therapists believed that work evaluation belonged to a newly established profession of vocational rehabilitation rather than occupational therapy.58 Occupational therapy involvement declined, and vocational counselors, vocational evaluators, and work adjusters were primarily the leaders in this field. There were, however, still a few occupational therapists who remained active in work programming.

A high point in the development of prevocational exploration and training techniques in the field of occupational therapy occurred in 1960.42 Rosenberg and Wellerson published an article on development of the TOWER (Testing, Orientation, and Work Evaluation in Rehabilitation) system in New York.84 The TOWER system was one of the first work sample programs to use real job samples in a simulated work environment.84 In 1959, Lilian S. Wegg gave the Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lecture on “Essentials of Work Evaluation” based on her experiences at the May T. Morrison Center for Rehabilitation in San Francisco. Wegg promoted the need for both sound testing procedures and training programs.100 Florence S. Cromwell, a president of the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA), established norms for disabled populations on certain prevocational tests while evaluating the performance of adults with cerebral palsy at the United Cerebral Palsy Organization.42 Cromwell continued to be an important advocate of work-related therapy in the ensuing decades.

Occupational behavioral theory, which emerged in the mid-1960s and early 1970s, offered a return to the profession’s concern for occupation. Mary Reilly, an early proponent of occupational behavior theory and a 1962 Eleanor Clark Slagle lecturer, believed that productive activity as treatment was the unique contribution of occupational therapy.42 Occupational behavior theory advocated that persons can achieve healthy living only through a balance between work, rest, and play.

The increasing numbers of industries in the late 1970s and early 1980s introduced a whole new arena for occupational therapists: industrial rehabilitation and work hardening.42 Work hardening used actual work tasks in a simulated structured work environment, generally in community-based settings.5 Occupational therapists used their knowledge of neuromuscular characteristics, including range of motion (ROM) and endurance, along with task analysis skills and knowledge of the psychosocial aspects of work in evaluating, planning, and implementing a work-hardening program.

In 1989, the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF) developed work-hardening standards requiring an interdisciplinary approach.15 The interdisciplinary team consisted of occupational therapists, physical therapists, psychologists, and vocational specialists.

The Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA; Public Law 101-336) was important legislation that opened major markets for occupational therapists.42 Occupational therapists were involved in providing both work training for persons with disabilities and assistance to employers in meeting the requirements of the ADA. This legislation continues to have important implications for work practice.23 (See Chapter 15 for more information on the ADA.)

In 1992, the AOTA defined work as “all productive activities and included life roles such as homemaker, employee, volunteer, student, or hobbyist.”4 This document was replaced in 2000 by the statement “Occupational Therapy Services in Facilitating Work Performance.” This statement asserts that “occupational therapists and occupational therapy assistants contribute to the delivery of services for the promotion and management of productive occupations as well as the prevention and treatment of work-related disability.”2

In 2002, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) unveiled a comprehensive approach to ergonomics to reduce the incidence of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) in the workplace. Their four-pronged, comprehensive approach includes guidelines, enforcement, outreach and assistance, and a national advisory committee on ergonomics.

Occupational therapists have traditionally consulted and continue to consult with employers and employees on making recommendations about equipment, posture, and body mechanics to prevent injuries. Ergonomic intervention continues to be an area of many opportunities for occupational therapists who have received additional training and education in the area of ergonomics.

Role of the Occupational Therapist in Work Programs

Occupational therapists and occupational therapy assistants play an important role in helping individuals participate in all aspects of work. According to the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process, second edition, work is an area of occupation that is defined by Mosey as “activities needed for engaging in remunerative employment or volunteer activities,” including the following: “employment interests and pursuits, employment seeking and acquisition, job performance, retirement preparation and adjustment, volunteer exploration, and volunteer participation.”1 Occupational therapy practitioners provide services to those with limitations in the area of work performance. The occupational therapist focuses on identifying and analyzing the problem and selecting and/or designing appropriate assessments and interventions for solution of the problem. According to the statement “Occupational Therapy Services in Facilitating Work Performance,” “problems in work performance can arise from physical, sensory, cognitive, perceptual, psychological, social, or developmental changes. Therefore, occupational therapy practitioners provide work-related services in a variety of settings, including, but not limited to, acute care and rehabilitation facilities, industrial sites, and office environments, psychiatric treatment centers and in the community.” Two key services are provided in these settings, “evaluation and intervention, which includes consultative, preventive, restorative, and compensatory services.”2 This chapter describes the range of work evaluations and interventions in which occupational therapists are involved in assisting people in actively participating in meaningful work roles.

Industrial Rehabilitation

The range of services provided to injured workers and industry is often encompassed by the terms “industrial” or “occupational rehabilitation.” These terms will be used interchangeably in this chapter. Industrial rehabilitation includes functional capacity evaluation (FCE), vocational evaluation, job demands analysis (JDA), worksite evaluation, pre-employment screening, work hardening/conditioning, on-site rehabilitation, modified/transitional employment, education, ergonomics, wellness, and preventive services. Occupational therapists are integral in providing these services, and this area of practice provides a tangible way for therapists to experience the tremendous reward of seeing lives changed through their efforts. The AOTA has developed a Work and Industry Special Interest Section (WISIS) for those who are involved in or wish to know more about this area of specialization.

Functional Capacity Evaluation

An FCE is an objective assessment of an individual’s ability to perform work-related activity.28,52 These functionally based tests have been used since the early 1970s to assist in making return-to-work decisions and were primarily performed by occupational and physical therapists.38 Today, however, the results of such an evaluation can be used in many different ways and they are performed by a multitude of disciplines. Occupational therapists are remarkably qualified to conduct FCEs because of their education and background in task analysis.2,3 An FCE can be used to set goals for rehabilitation and readiness for return to work, assess residual work capacity, determine disability status, and screen for physical compatibility before hiring a new employee and case closure.75

An FCE usually consists of a review of medical records, an interview, musculoskeletal screening, evaluation of physical performance, formation of recommendations, and generation of a report.45 Evaluation of physical performance usually takes the form of assessing the client’s physiology, both cardiovascular and muscular endurance, during the course of strength, static, and dynamic tasks. The report usually contains information regarding the overall level of work, tolerance for work over the course of a day, individual task scores, job match information, level of client participation (cooperative or self-limited), and interventions for consideration.45,50

A wide variety of FCEs are currently used in practice today, both commercially available systems and evaluations developed by individual therapists or clinics (Box 14-1, Figure 14-2).

FCEs can be (1) all-inclusive when looking at case closure or settlement; (2) job specific when making a match between a person’s abilities and the job description, such as “cashier at XYZ store” or a broader occupational title such as “cashier”; or (3) injury specific, such as an upper extremity evaluation after bilateral carpal tunnel release. Joe, the 26-year-old man with T11 paraplegia, could benefit from a job-specific FCE to determine whether he can meet the physical demands of the alternative job as a laundry attendant.

A well-designed FCE is comprehensive, standardized, practical, objective, reliable, and valid.45,50,86

A comprehensive FCE will include all of the physical demands of work as defined by the Dictionary of Occupational Titles (DOT) published by the U.S. Department of Labor and last revised in 1991 (Box 14-2).97 The main focus of Joe’s FCE will be on the physical demands of work that he can still reasonably do from the wheelchair, such as lifting, sitting, carrying, pushing, pulling, balancing, reaching, handling, fingering, feeling, talking, hearing, and seeing.

It is also important for the individual being tested to understand the correlation between the test items and the functions of the job. The application of meaningful activity can improve individuals’ cooperation during testing and encourage maximum effort. For example, an individual who performs secretarial duties may have difficulty understanding the need to test her ability to climb ladders if she does not actually perform this function during the course of her job.1,75

An FCE needs to be practical in terms of length of testing, cost, space, and report generation.50,75

Standardization in FCEs means having a procedure manual, task definitions and instructions, a scoring methodology, and equipment requirements and set-up.50,52,76 This type of structure helps ensure that individuals are being assessed in a fair and consistent manner and demonstrates the effort to minimize observer bias. Verbal instructions are critical in establishing rapport between the evaluator and the individual being tested. During the initial interview, the tone is set for the course of the evaluation, and the individual’s trust in the evaluator is implicit in maximizing cooperation and effort during the evaluation.50 Objectivity is not limited to weights, distances, heights, or some other numeric quantity; subjective measures can be made objective with operational definitions. Objectivity during the course of an FCE does not exclude clinical judgment and decision making, but it does require the measure to be as free as possible of examiner bias.86 This includes physical performance, as well as client cooperation during testing. Objectivity is accomplished through standardization of the testing protocol and a structured scoring methodology.

The most important aspects of an FCE are reliability and validity of the testing protocol. Two types of reliability are deemed to be important in an FCE: interrater and test-retest reliability.52 Interrater reliability in an FCE means consistency; if two therapists administer the same test to the same client, will they get the same results?45 King and Barrett state that “test-retest reliability or intra-rater reliability refers to the stability of a score derived from one administration of an FCE to another when administered by the same rater.”45 Being able to establish reliability is the first step in determining the validity or accuracy of the results.86 If there is not agreement between evaluators, it is difficult to determine whose results are correct.45 Once reliability has been proved, validity can be assessed. The term validity is used in many ways, often with significance placed on issues surrounding sincerity of effort. In scientific terms, validity means accuracy; in other words, does the FCE provide results that truly describe how the client can perform at work?50,86

There are several types of validity, with content, criterion (both concurrent and predictive), and construct validity having the most impact on the results of an FCE.45,50 Content validity is the easiest to establish in an FCE because this measure refers to whether the evaluation tests the physical demands of work, as defined by a panel of experts, by job analysis, or by a recognized document such as the DOT.50,52,75,97

Criterion validity refers to whether conclusions can be drawn from the measures taken, and in an FCE this refers to whether a person can actually perform at the level demonstrated during testing.45,50,52 Criterion validity is often determined by comparing the methodology in question with a “gold standard”—another instrument that has been proved to be reliable and valid.45,50,52 This is difficult to do in an FCE because there are a limited number of available assessments with proven reliability and validity to compare against and because other methods, such as comparing the person’s tested ability with the actual work level, can be seriously flawed.50,52,56 Criterion validity includes concurrent and predictive validity.

Concurrent validity refers to the ability of a test to measure existing abilities, and in an FCE this would be demonstrated by the test’s ability to determine which clients can perform at a given level and which clients cannot perform at a given level.45,50,52

Predictive validity is indicated by the test’s capacity to predict future ability and has great value in an FCE by determining who can safely return to work and remain without injury.45,50,59 The first FCE to be studied for validity and published in peer-reviewed literature was developed by the occupational therapist Susan Smith and has served as an important contribution to the knowledge base.92 Without reliability and validity, a referral source cannot know whether the results of the evaluation would vary if the individual were tested by another therapist or whether the results are accurate.45,50,52

Vocational Evaluations

Work evaluations, or vocational evaluations, are “a comprehensive process that systematically uses work, real or simulated, as the focal point for vocational assessment and exploration to assist individuals in their vocational development.”25 According to CARF, the following factors are addressed in the traditional vocational evaluation model: physical and psychomotor capacities; intellectual capacities; emotional stability; interests, attitudes, and knowledge of occupational information; aptitudes and achievements (vocational and educational); work skills and work tolerances; work habits; work-related capabilities; and job-seeking skills.35 These assessments can last from 3 to 10 consecutive days, depending on the goals of the assessment. Vocational evaluators generally conduct these types of assessments in private vocational agencies; however, some occupational therapists have been involved in conducting these evaluations in public and private medical or nonmedical settings as well. Vocational rehabilitation, worker’s compensation, and long-term disability carriers pay for these services, but most medical plans do not.

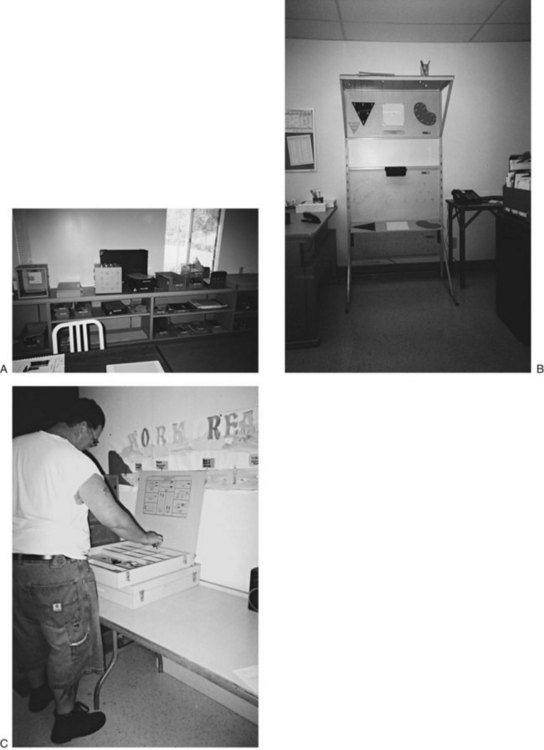

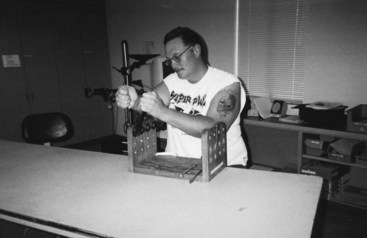

Standardized work samples such as the Valpar Component Work Sample System or the Jewish Employment Vocational Services are used to assess specific skills in the areas of data or things (Figure 14-3). Dexterity tests such as the Bennett Hand Tool, Crawford Small Parts, and Purdue Pegboard are used to evaluate motor skills (Figure 14-4).35 When no standardized work samples are available to assess the specific skills needed for a particular occupation, specially designed situational assessments are also used to create real-life work situations that are related to actual work tasks that would be conducted on particular jobs. For example, a person who is interested in working as a floral arranger could have her motor skills evaluated to see whether she has the coordination, energy, and strength and effort to grip and manipulate tools to cut the stems of flowers and plants and arrange them in floral containers. Individuals can also be evaluated in real worksites and perform actual job tasks that one would perform on the job.

FIGURE 14-3 A, Valpar and JEVS work samples. B, Valpar 9 Total Body Range of Motion work sample, which is used to evaluate functional abilities such as standing, bending, crouching, reaching, and gross manipulation and handling. C, The Valpar 10 Tri-Level Measurement is used to evaluate a person’s ability to follow a multistep sequence to inspect metal parts with various jigs and tools.

FIGURE 14-4 The Bennett Hand Tool is a dexterity test to assess a person’s ability to use hand tools.

There are generally two different types of vocational evaluation: a general vocational evaluation and a specific vocational evaluation. A general vocational evaluation is a comprehensive assessment to evaluate a person’s potential to do any type of work. For an individual who has never worked, does not have a job to return to, or cannot return to the previous job because of a disability, this type of evaluation is beneficial in determining one’s aptitudes, abilities, and interests to explore all reasonable options for work. For example, Henry, the roofer who experienced a traumatic brain injury from a fall while working, could benefit most from a general vocational evaluation to explore other options for employment. A general vocational evaluation could help identify other vocational interests and abilities by exploring a person’s cognitive and motor skills and physical and mental tolerances that could be applied to a different occupation. A specific vocational evaluation assesses a person’s readiness to return to a particular occupation. For a person who has suffered a stroke and wants to return to work as a general office clerk, a specifically tailored vocational evaluation to assess the person’s ability to return to this particular type of work can be done. Clerical work samples and specially designed situational assessments that gauge the person’s ability to multitask, pay attention to detail, file, answer a telephone, and take messages can be incorporated as an integral component of the vocational evaluation.

Job Demands Analysis

Assessing the physical demands of a job by JDA is often beneficial in the rehabilitation process inasmuch as recommendations for initiation or return to work require objective information about both the client’s abilities and the job itself. A well-written job description that includes the essential tasks of the job, physical requirements, cognitive aptitudes, educational requirements, equipment operated, and environmental exposure assists in selecting suitable candidates for employment, setting compensation packages, and making appropriate return-to-work decisions after an injury.8

A JDA does not need to be confused with ergonomic evaluations or identification and abatement of hazards. A JDA seeks to define the actual demands of the job, whereas ergonomic evaluations and hazard assessment focus more on work practice and risk for injury secondary to postural or manual material-handling extremes or excesses.7 Certainly, these areas can overlap, but it is important to be clear about the differences and the reasons behind the request for information and to use suitable methods for each.7

Approaches to a JDA include questionnaires, interviews, observations, and formal measurement.7 It is common to interview incumbents or supervisors about the job requirements.75 Such an informal approach often leads to narrative descriptions with little functional information and questionable accuracy of demand estimates.36,62,75 As with other types of assessment, it is important to have an objective process for analyzing the demands of the job. In the context of attempting to make return-to-work decisions based on matching the results of an FCE with the job description, many FCEs include a JDA component.50 However, these are often subjective interviews with the client and can lack accuracy regarding the physical demands.

The occupational therapist who was working with Joe contacted the employer and conducted a JDA to obtain a complete picture of the job demands and requirements of the laundry attendant position. The occupational therapist spoke to the supervisor, as well as to other employees while they were performing the actual job at the worksite. Being able to actually observe the job being done in the real work environment allowed the occupational therapist to gather the information needed to adequately assess Joe’s ability to carry out the essential functions of this job.

A standardized classification system is crucial to ensure consistency in terminology and among professionals. The DOT defines the physical demands of work and defines occupations in the United States (Tables 14-1 through 14-3).97 It provides definitions of the overall level of work, strength demands, and frequencies of the physical demands.97,98 Many countries around the world also refer to the DOT as their primary reference for generic occupational descriptions.

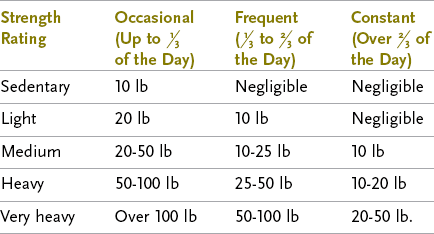

TABLE 14-1

Definitions for Overall Level of Work

| Level of Work | Definition |

| Sedentary | Exerting up to 10 lb of force occasionally or a negligible amount of force frequently to lift, carry, push, pull, or otherwise move objects, including the human body. Sedentary work involves sitting most of the time but may involve walking or standing for brief periods. Jobs are sedentary if walking and standing are required only occasionally but all other sedentary criteria are met |

| Light | Exerting up to 20 lb of force occasionally, up to 10 lb of force frequently, or a negligible amount of force constantly to move objects. Physical demand requirements are in excess of those for sedentary work. Even though the weight lifted may be only a negligible amount, a job should be rated light work (1) when it requires a significant degree of walking or standing, (2) when it requires sitting most of the time but entails pushing or pulling arm or leg controls, or (3) when the job requires working at a production rate pace entailing constant pushing or pulling of material even though the weight of the material is negligible. Note: The constant stress and strain of maintaining a production rate pace, especially in an industrial setting, can be and is physically demanding on a worker even though the amount of force exerted is negligible |

| Medium | Exerting 20-50 lb of force occasionally, 10-25 lb of force frequently, or greater than negligible and up to 10 lb of force constantly to move objects. Physical demand requirements are in excess of those for light work |

| Heavy | Exerting 50-100 lb of force occasionally, 25-50 lb of force frequently, or 10-20 lb of force constantly to move objects. Physical demand requirements are in excess of those for medium work |

| Very heavy | Exerting force in excess of 100 lb of force occasionally, in excess of 50 lb of force frequently, or in excess of 20 lb of force constantly to move objects. Physical demand requirements are in excess of those for heavy work |

Data compiled from US Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration: Revised dictionary of occupational titles, vols I and II, ed 4, Washington, DC, 1991, US Government Printing Office; and US Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration: The revised handbook for analyzing jobs, Indianapolis, Ind, 1991, JIST Works.

TABLE 14-2

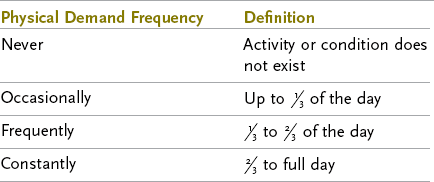

Definitions of Physical Demand Frequencies

Data compiled from US Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration: Revised dictionary of occupational titles, vols I and II, ed 4, Washington, DC, 1991; and US Government Printing Office; US Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration: The revised handbook for analyzing jobs, Indianapolis, Ind, 1991, JIST Works.

TABLE 14-3

Strength Demands of Work: Frequency of Force Exertion or Weight Carried

Data from US Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration: Revised dictionary of occupational titles, vols I and II, ed 4, Washington, DC, 1991, US Government Printing Office.

The DOT was last revised in 1991, and in the early 1990s the U.S. government made the decision to not revise the DOT again but instead create a new format for classifying occupations.26 The intent was to create a more generic classification system or framework for defining work. The American Institutes of Research (AIR) was awarded a contract by the Utah Department of Employment Security on behalf of the U.S. Department of Labor, and they developed O*NET, an online, searchable database for information about occupations. Although the format includes an enormous amount of data, its definitions can make it difficult for rehabilitation professionals to use in a qualitative fashion.74 O*NET, however, is not intended to take the place of the DOT but rather to provide a more structured approach for “career exploration.”74 It is recommended that both the DOT and O*NET be consulted when obtaining occupational information.26

In terms of recent legislation that has an impact on employment law, both the ADA and the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission (EEOC) define essential tasks as being the reason that the job exists.6,7 The ADA further defines essential tasks as those that are highly specialized (i.e., the reason that the incumbent was hired to perform the job) and that there are a limited number of people available at the job site to perform the tasks.6 During the course of a JDA it is important to distinguish between tasks that are essential and those that are not. This can be challenging because it is a nontraditional way for both the employee and the employer to look at the job. It is important that both hiring and return-to-work decisions be based on job descriptions that define the essential tasks to be congruent with both the ADA and EEOC language.

Jobs are composed of the tasks that are performed, the physical demands that make up the tasks, and the frequency with which the physical demands are performed, including weights handled, forces exerted, and distances both ambulated and reached.7 The frequency of each physical demand must be weighted appropriately for the given duration of each task because there is often a significant difference in the amount of time spent on each task during the workday. For example, the job of “loader” in ABC warehouse is composed of two tasks: (1) loading crates with boxes and (2) wrapping the crate with packing tape when loaded. The loader completes 48 cycles of loading and taping in an 8-hour shift, with loading the crate taking approximately 80% of the work shift. The boxes weigh 10 lb each. To correctly assess the overall level of work, the amount of weight lifted must be determined, as well as the frequency of the manual materials handling.

Task 1 is composed of the physical demands of lifting, carrying, stooping, walking, reaching, handling, and standing. Task 2 is composed of walking, reaching, handling, fingering, and standing. To correctly sum the amount of the physical demands for the job of loader, one must determine how much time is spent on each physical demand within each task and then account for the proportion of the time that the task is performed during the workday. This type of assessment can be performed manually, as well as with the application of various software protocols available in the marketplace.

Whatever methods are selected, clinicians should strive to provide an accurate picture of the job and its requirements, with an emphasis on functional demands for easier application in the rehabilitation continuum.

Work Hardening/Work Conditioning

The idea of using work for rehabilitation is at the very core of occupational therapy. In the 1970s, the idea of occupational rehabilitation developed from the necessity of improving strategies to control work-related injuries.19,44,51,73 Work hardening was first illustrated conceptually by Leonard Matheson, a psychologist at Rancho Los Amigos who worked very closely with Linda Dempster, an occupational therapist, in developing his material.44,51,73 The goal was then and still remains rehabilitation of injured workers, maximization of their function, and returning them to work as quickly and safely as possible. The delivery system for this type of rehabilitation has evolved over time from a lengthy hospital-based program, to structured interdisciplinary programs in outpatient settings, to the more progressive partnership between outpatient intervention and transitional work, as well as to rehabilitation occurring at the workplace in company-sponsored clinics. In the 1980s, CARF developed guidelines for work-hardening programs and offered certification for a fee through adherence to their guidelines and periodic surveys.19,44,51,73 In 1991, a committee from the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) developed another set of principles for clinics that wanted to follow recognized standards but did not desire to undertake the CARF accreditation process.19,44,51

Work hardening refers to formal, multidisciplinary programs for rehabilitating an injured worker.19,44,51,73 The disciplines represented on the team can often include occupational and physical therapists and assistants, psychologists, vocational evaluators and counselors, licensed professional counselors, addiction counselors, exercise physiologists, and dieticians.19,44,51 The programs typically range from 4 to 8 weeks and consist of an entry and exit evaluation (usually an FCE or a derivative thereof), a job site evaluation, graded activity, both work simulation and strength and cardiovascular conditioning, education, and individualized goal setting and program modification, with the goal of return to work at either full or modified duty.19,44,51 Actual equipment from the job is preferred during the work simulation to maximize cooperation of the worker and more closely replicate the actual demands of the job.44 Work conditioning is more often defined as physical conditioning alone, which covers strength, aerobic fitness, flexibility, coordination, and endurance and generally involves a single discipline.19,42,44 Both approaches involve evaluation of the worker to establish a baseline from which to plan treatment and measure progress.

Motivational issues are a constant concern and are often thought to be at the forefront of unsuccessful return to work.91 Maladaptive behavior regarding return to work can develop in an injured worker as a result of depression, financial issues, family pressures, and feelings of being manipulated by the “system.”91 This can lead to employer mistrust, interest in litigation, and a need to exaggerate symptoms. Fraud on the part of the injured worker is also an issue.91 Employer indifference is a concern and can have a remarkable impact on a worker’s attitude toward returning to the job.91 Surveys of attitudes among employers have indicated that activity on the part of the employer can affect costs; as many as 90% of respondents indicated that how well the employee perceived that he or she was treated at the time of the injury was associated with decreased costs as a result of the injury.91

Think about Lorna, the upholsterer who is experiencing hand problems, and the difficulties that she is experiencing at work. An occupational therapist could evaluate her symptoms and her job description and make suggestions to the employer about modifying her job demands so that she can continue to work during treatment. This demonstrates to Lorna that her well-being matters and can help her have a positive outcome with treatment.

Ensuring a positive outcome for the injured worker requires early intervention and a customized plan of treatment to address the various areas affected by the injury, including both physical and psychosocial.91 Incorporation of a multidisciplinary team allows the patient to have the benefit of many areas of expertise working toward his or her common good. Intervening and initiating the rehabilitation program as soon as possible following the injury dramatically increase the chance for successful return to work. Based on a study of 5620 worker’s compensation beneficiaries, there was a 47% return-to-work rate in workers referred to rehabilitation within the first 3 months after injury, with a cost savings of 71%. When referred during months 4 through 6, the rates dropped to 33% for return to work and 61% for cost savings. For those referred beyond 12 months after injury, only 18% returned to work and cost savings dropped to 51%.91

Transitional work and modified duty programs involve a combination or a progression of acute rehabilitation and return to work at a level consistent with the individual’s current ability, with the goal of returning to work at full duty or maximizing the individual’s work capacity. An example of transitional duty would have a worker performing work-conditioning activities under supervision in an outpatient clinic from 8 to 10 a.m., going to the worksite and performing the less physically demanding portions of his job from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m., breaking for lunch, and then returning to the “lighter” duties of the job for the duration of the shift. More regular duty activities are added under supervision as the worker’s skill and strength improve, with eventual return to full duty. This type of structure provides a much better environment for the worker to be involved in the work culture and allows coworkers and supervisors to participate in job modification and overall recovery of the injured worker.91 Modified duty follows a similar path but typically does not include the clinical portion of the day. There are challenges to return to work at less than full duty, however, with some employers not wanting workers to return to the site unless they are at “100%.” It is imperative to demonstrate the benefit to the company and the employee, both economically and psychologically, of early transitional return to the long-term success of returning the employee to the workforce.

Industrial rehabilitation programs will continue to change as the tides of economy, industry needs, and legislation move forward. Occupational therapists are key in directing the changes that lie ahead.

Worksite Evaluations

Worksite evaluations are on-the-job assessments to determine whether an individual can return to work after onset of a disability or whether a person can benefit from reasonable accommodations to maintain employment.41,95 For example, a man who worked at a manufacturing company as a machine operator incurs a stroke and the employer is willing to take him back as long as he can meet the physical and cognitive demands of the job. An occupational therapist can go to the worksite to evaluate the person’s ability to safely and adequately operate the machinery and carry out the essential functions of the job. Consider another example. A person who previously worked as an office clerk without any difficulty is now experiencing extreme fatigue, pain, and muscle weakness with repetitive tasks as a result of post-polio syndrome. This person could benefit from a worksite evaluation to identify reasonable accommodations to allow her to continue working at this job while minimizing her symptoms. Several factors are assessed at the worksite with the worker present: the essential functions of the job, the functional assets and limitations of the worker, and the physical environment of the workplace.55

A worksite evaluation is usually conducted after a job analysis has been done. Larger companies may already have information on job analyses done on specific jobs. If a job analysis has not been done, the occupational therapist can conduct a job analysis if the employer is willing, or a job description could be obtained from the employer before going out to the worksite. If there is no written job description, a phone call to the supervisor/manager of the worker should be made to obtain verbal information regarding the essential functions of the job and the physical and cognitive requirements for the job. After this information is obtained, the occupational therapist schedules a time with the employer and the worker to meet at the worksite. This is exactly what happened with Joe as he prepared to switch from the job of janitor to laundry attendant at the hotel and spa. After the occupational therapist conducted the job analysis, Joe met with both the occupational therapist and the employer at the worksite for the worksite evaluation.

When the occupational therapist meets the employer and worker at the worksite, the occupational therapist assesses the work, the worker, and the workplace.47 The evaluation begins with an analysis of the essential functions that may require accommodation.95 The occupational therapist should have an idea of what these functions are based on the information obtained before going to the worksite. The desired outcome of the work tasks should be emphasized, not just the process of performing the essential function.95 The occupational therapist should find out certain details, such as how the outcome will be affected if a particular task is done incorrectly, in a different sequence, or omitted; whether there are quotas, standards, or time constraints that must be met79; and whether the frequency with which a task is done will affect the outcome.

Activity analysis is a useful tool for evaluating a person at the worksite.11 It can be used to address all areas, including motor, sensory, cognitive, perceptual, emotional and behavioral, cultural, and social. When assessing a person’s ability to carry out the essential functions of the job, the occupational therapist has expertise in breaking down the tasks and determining the parts of the task with which the worker is having difficulty or may have difficulty over the course of a workday. The occupational therapist can suggest accommodations to allow the worker to carry out the essential functions of the job.

The final step in the worksite evaluation is to assess the work environment. The environment outside the immediate work area should be evaluated (parking if driving or access to public transportation; access into the building, break room, and restroom), as well as the workstation itself. All work areas that the worker may use need to be investigated to identify obstacles and solutions to increase accessibility. The location and placement of machines, supplies, and equipment that the worker needs to access should be assessed, as well as other environmental factors such as lighting, temperature, and noise level.

Taking photographs or video recordings at the worksite can be very useful; however, permission must be obtained from the employer as well as the worker to do so. The occupational therapist should also bring a tape measure to measure the height of work surfaces, width of doorways, and other factors, depending on the person’s needs. Drawing a layout of the work area to scale on graph paper is also very helpful, especially when the worker is in a wheelchair. Critical measurements can be recorded on the diagram.

The outcome of the worksite evaluation is to determine whether the person can safely and adequately carry out the essential functions of the job with or without any reasonable accommodations. Ergonomic principles (addressed in the following section) should be considered and applied when recommending reasonable accommodations. The process of identifying reasonable accommodations requires cooperation between the person with the disability, the employer, and the occupational therapist.79 Each person has valuable insights and information to contribute to the process of identifying the best accommodations. The Job Accommodation Network (JAN) is a service provided by the Office of Disability Employment Policy (ODEP) of the U.S. Department of Labor’s and is the best resource for assisting employers and disabled workers in making reasonable accommodations (http://askjan.org).87 Their Website points out that most job accommodations are not usually expensive. According to the JAN, more than half of all accommodations cost nothing. The JAN offers one-on-one guidance on workplace accommodations, the ADA, and self-employment options for people with disabilities. JAN consultants can be contacted both over the phone and online. JAN’s toll-free number is (800)526-7324. The occupational therapist analyzes the need for modification of the equipment that the worker is using or modification of the workplace to help the person perform with greater efficiency, effectiveness, and safety.5

After the worksite evaluation is completed, a report is prepared and sent to the qualified employee, the referring party, and the employer. The problem areas that relate to the essential job functions should be listed clearly, as well as the accommodations necessary to solve them. If training is necessary to use a recommended accommodation, sources for the training should be identified. If commercially available equipment is recommended, exact model numbers, local sources, and approximate expenses should be provided.95 If custom equipment needs to be fabricated, sources, cost estimates, and the amount of time required to fabricate the equipment should be included as well. The report should summarize the findings of the evaluation and the accommodations that were recommended.

After Joe’s worksite evaluation, it was determined that he could safely and dependably carry out the essential functions of the job from his wheelchair. Just one accommodation was recommended and implemented. Since it gets very hot in the laundry room and Joe is sensitive to the heat, the employer agreed to purchase additional fans to ventilate the room better, as well as allow the door to the laundry room to be propped open. The employer agreed to schedule Joe’s shift in the evening or early morning when it was cooler to avoid having to work in the heat of the day.

The occupational therapy practitioner thus evaluates the worker, the work, the workplace, and the relationship among them. Therapeutic intervention is used when deficits in performance are found. The occupational therapist can modify the way that the worker performs the work or modify the work environment to allow the worker to perform optimally.

Ergonomics

All aspects of the domain of occupational therapy must be in harmony for people to fully engage in the occupation of work. The activity demands of the job and the context in which the job is performed must fit with the employee’s abilities and physical/psychosocial makeup. Any mismatch between the activity demands of the job and context, individual client factors, and performance patterns will interfere with successful execution of the appropriate performance skills required to do the job.

Occupational therapists use the science of ergonomics to assist clients in fully engaging in the occupation of work. Ergonomics addresses human performance and well-being in relation to one’s job, equipment, tools, and environment. The goal of ergonomics is to improve the health, safety, and efficiency of both the worker and the workplace.67 The term ergonomics is derived from the Greek words ergos, meaning “work,” and nomos, meaning “laws”—hence the laws of work.20 The Polish educator and scientist Wojciech Jastrzebowski (1799-1882) introduced the term ergonomics in the literature about 150 years ago.19 However, the concept of ergonomics—that there is some connection between physical well-being and the type of work performed—is as old as humanity: “From the very first tool of the Stone Age, humans have tried to find better ways of working, taking advantage of human talents and making up for human shortcomings.”56

The idea behind ergonomics is that every worker brings his or her own unique set of performance skills, performance patterns, and client factors to the workplace. Many times work settings and work processes are designed to satisfy space and budget limitations and the demands of productivity and aesthetics. When these designs fail to take into account the people who will be using the work setting and process, injury and inefficiency can result. Finding a way to match individual employees’ strengths and limitations with the context and activity demands of a job can improve both worker safety and workplace productivity.

The principles of ergonomics help address a variety of work-related issues. Common issues include workplace and work process design, work-related stress, the disabled and aging workforces, tool and equipment design, architectural design, and accessibility. Ergonomic intervention can be applied proactively, preventing problems before they occur, or reactively, adjusting the worker-job-context “fit” when problems do occur. Many occupational therapists use ergonomic principles as part of their comprehensive rehabilitation or wellness and prevention client-centered programs. A few occupational therapists specialize in ergonomics and become professional ergonomists.

With regard to ergonomic services, the occupational therapist’s client base may include the individual worker, workers in the context of employee groups, and/or the employer itself. The environment for an occupational therapist providing ergonomic services is generally at the client’s place of work. These occupational therapists must become skilled in navigating what can be an unfamiliar business world with its unique lingo, social norms, and traditions. However, an occupational therapist providing ergonomic services shares a similar focus with occupational therapists in all areas of practice, that is, a focus on marketing and sale of the product (in ergonomics—wellness), cost-effectiveness, definable outcomes, and client satisfaction.

Occupational therapists are not the only professionals suited to specialize in the field of ergonomics. Ergonomics professionals come from a variety of backgrounds. It is not unusual to see ergonomists who have been academically trained in industrial hygiene, engineering, safety, business administration, human resources, medicine, physical/occupational rehabilitation, psychology, architecture, epidemiology, or computer science.18 For the occupational therapist, the road to becoming a professional ergonomist can take many paths. Box 14-3 outlines a variety of methods for acquiring advanced knowledge and certification in the field of ergonomics.

For occupational therapists interested in the field of ergonomics, the holistic nature of occupational therapy training is an asset. The occupational therapist immediately understands that the goal of ergonomic intervention, or achieving a perfect fit between an individual worker and his or her job and context, is never simplistic. In the domain of occupational therapy, the worker component is composed of performance skills, performance patterns, and client factors (Box 14-4). The job component is composed of activity demands, both of the job tasks and of tools/equipment. Engaging in the occupation of work occurs in a variety of contexts, including the environment and organization, as well as the worker’s personal, cultural, social, and spiritual contexts.

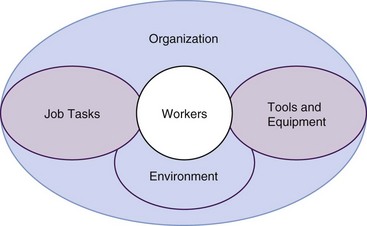

Observing independent aspects of the domain offers the observer limited insight. Rather, it is the interactions between the various aspects of the domain that reveal the whole picture. This way of looking at worker performance via the interactions of all aspects of the domain of occupational therapy is known as system theory. Rannell Dahl, MS, OTR, explains that the “components of work systems are workers, job tasks, tools and equipment, work environments, and organizational structure, and the interactions among these components.”18 Dahl offers an excellent schematic of this concept of the ergonomics work system (Figure 14-5).

FIGURE 14-5 Dahl’s ergonomics work system. (From Dahl R: Ergonomics. In Kornblau B, Jacobs K, editors: Work: principles and practice, Bethesda, Md, 2000, American Occupational Therapy Association.)

In his groundbreaking text Conceptual Aspects of Human Factors, David Meister explained that in human factors (ergonomics), the system concept is the belief that human performance in work can be meaningfully conceptualized only in terms of organized wholes. He emphasized the fundamental Gestalt ideas that “the whole is more than the sum of its parts, that the parts cannot be understood if isolated from the whole, and that the parts are dynamically interrelated or interdependent.”59 Occupational therapists understand that one can conceive of worker performance only in terms of the interaction between performance skills, performance patterns, context, activity demands, and client factors. The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process supports this concept: “Engagement in occupation as the focus of occupational therapy intervention involves addressing both subjective (emotional and psychological) and objective (physically observable) aspects of performance. Occupational therapy practitioners understand engagement from this dual and holistic perspective and address all aspects of performance when providing interventions” (p. 628).1

Occupational therapist Jeffrey Crabtree adds that it is “the subjective meaning of the interactions in the human-work-machine-environment model [that] is central to occupational therapy and ergonomics.”16

The system theory does not discount the importance of the adequacy of independent aspects of the domain of occupational therapy. The quality of the work system can suffer if there are deficiencies or deviations in performance skills, performance patterns, context, activity demands, or individual client factors. Dahl explains that each component of the ergonomics work system (see Figure 14-5) “has its own set of characteristics that affect the performance of the work system”18 as a whole. It is here that ergonomic assessment and intervention seek to make a difference in the quality of our clients’ engagement in the occupation of work. The ergonomic practitioner modifies and strengthens certain aspects of the system with the goal of enhancing the overall quality of the work system interactions (i.e., improving the fit between the worker and his or her job).

Although it is beyond the scope of this chapter to comprehensively review the complete array of ergonomic design considerations, the following is a discussion of selected ergonomic design principles. There are, however, a multitude of resources for occupational therapists interested in learning more about the science of ergonomics. The authors of this chapter direct you to the references listed at the end of the chapter. Additionally, readers may be interested in the ergonomics information available through OSHA (www.osha.gov) and NIOSH (www.cdc.gov/niosh/).

When discussing ergonomic design it is important to understand that it is the relationship between the worker and work equipment, tools, or processes that is the problem, not any particular characteristic on either side. This can be confusing to an employer who orders expensive ergonomic tools and equipment for his or her workers and is disappointed when the workers continue to suffer work-related injuries and illnesses. The specialists in ergonomics must explain to their clients that a tool or piece of equipment is never in itself ergonomic; rather, it is the fit between a particular piece of equipment, tool, or process and the intended user of that equipment, tool, or process that creates a proper ergonomic situation.

Workstations

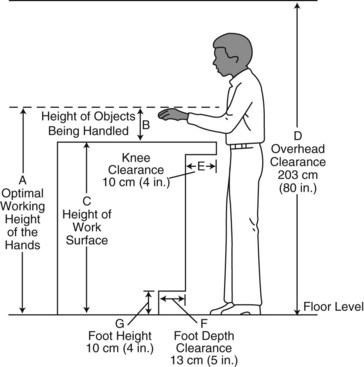

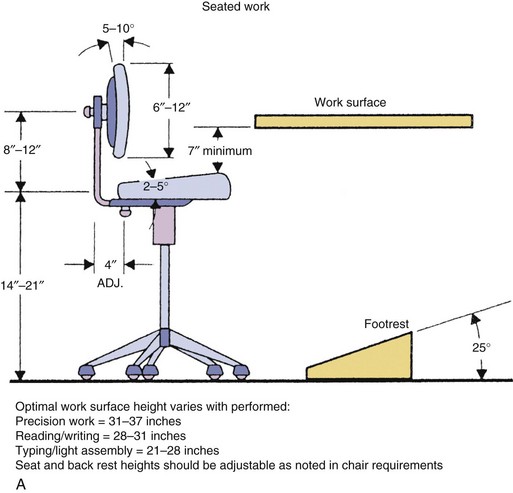

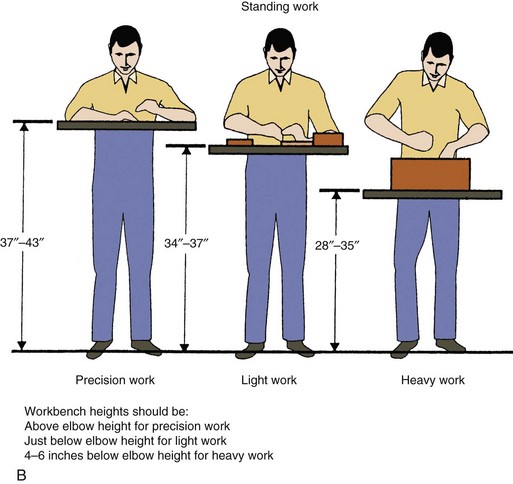

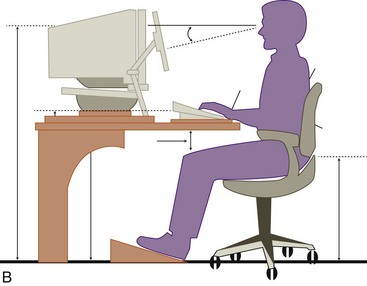

There are three major types of workstations: seated, standing, and combination sit/stand. The type of task being performed dictates the best choice. Seated workstations are best for fine assembly and writing tasks and when all required task items can be supplied and handled within comfortable arm’s reach in the seated work space. Items handled in a seated workstation should not require hands to work more than 6 inches (15 cm) above the work space, and the items handled should not weigh more than 10 lb (4.5 kg). For this reason, the height of the work surface should be above elbow height for precision work. Standing workstations are appropriate for all kinds of work tasks but are preferred when downward force must be exerted (i.e., packaging and wrapping tasks) and when frequent movement or multilevel reaching is required around the work area. Items weighing more than 10 lb (4.5 kg) should be handled in a standing workstation. Work surface heights for heavy work should be 4 to 6 inches (10 to 15 cm) below elbow height for heavy work. The combination sit/stand workstation is best for jobs consisting of multiple tasks, some best done sitting and some best done standing.22 Figure 14-6 shows the recommended dimensions for both a seated workstation and a standing workstation.

FIGURE 14-6 Recommended dimensions of workstations. A, Seated work. B, Standing work. (From Cohen AL, Gjessing CC, fine LJ, Bernard BP, McGlothlin JD: Elements of ergonomics programs: a primer based on workplace evaluations of musculoskeletal disorders, Washington, DC, 1997, US Government Printing Office.)

Seating

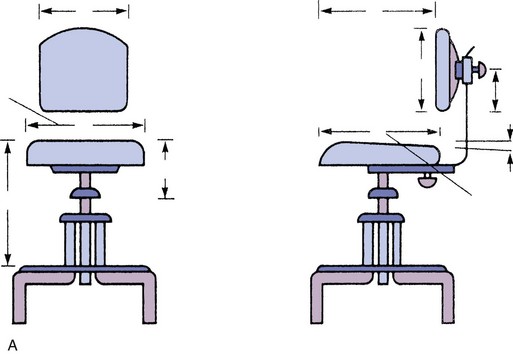

If seating is required, the design of the chair is of paramount importance for worker comfort and support. Poor seating leads to poor working posture. The result can be fatigue, musculoskeletal injury, and/or poor work performance. Although chair preference is highly variable among the population, there are some basic characteristics to consider. Chairs should be easily adjustable for height, backrest position, and seat pan tilt. Appropriate lumbar support is important. Seats upholstered in woven fabric are cooler and more comfortable in warmer work environments.22 Chair casters should match the flooring (i.e., hard floor versus carpet casters). A seat pan that is too deep will cut into the back of the leg and compromise lower extremity circulation. Sitting in a chair without the feet supported will also cause pressure on the back of the legs. When the worker is seated at the workstation and performing a task, both feet should be supported on the floor or a footrest. Choosing a seat pan with a front-edge “waterfall” design will also decrease pressure on the back of the legs. Armrests are an area of controversy but should generally be provided when the work task requires the arms to be held away from the body.37 Figure 14-7, A, illustrates the recommended chair characteristics for generalized seated workstations. Figure 14-7, B, illustrates a seated position for computer users.

FIGURE 14-7 A, Recommended chair characteristics. Dimensions are given from both front and side views for width (A), depth (E), vertical adjustability (D), and angle (I) and for backrest width (C), height (F), and vertical (H) and horizontal (G) adjustability relative to the chair seat. The angle of the backrest should be adjustable horizontally from 12 to 17 inches (30 to 43 cm) by either a slide adjust or a spring and vertically from 7 to 10 inches (18 to 25 cm). Adjustability is needed to provide back support during different types of seated work. The seat should be adjustable within at least a 6-inch (15-cm) range. The height of the chair seat above the floor with this adjustment range will be determined by the workplace, with or without a footrest. B, Proper seated position for a computer user. (A, From Eggleton E, editor: Ergonomic design for people at work, vol 1, New York, NY, 1983, Van Nostrand Reinhold; B, from Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Working safely with video display terminals, Washington, DC, 1997, US Government Printing Office, available at: www.osha.gov/ Publications/osha3092.pdf.)

Visualizing the Job Task

Visual factors to consider are the location of task items and lighting. Again, recommendations depend on the type of task being performed. The goal is clear, direct viewing without straining the eyes or neck. Tasks should be located as directly in front of the worker as possible. Tasks requiring close-range viewing should be positioned 6 to 10 inches (15 to 25 cm) above the work surface. Minimum and maximum viewing distances depend on the size of the object being viewed. Bifocal eyeglass wearers have difficulty observing any object closer than 7 inches (18 cm) in front of the body that is above eye level or near the floor. Additionally, bifocal wearers have difficulty focusing on signs or dials located 24 to 36 inches (61 to 91 cm) in front of them.20

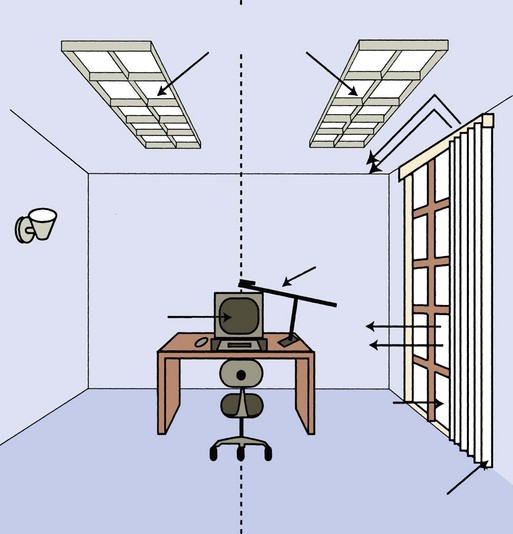

Three basic lighting factors need to be considered for performance of work: quantity, contrast, and glare. Lighting should be adequate for the worker to perform the job task, but not so bright that it causes discomfort. General work environment illumination is typically provided by sunlight and light fixtures at 50 to 100 foot-candles (ft-c). Computer users may find that this amount of illumination washes out the display screen and causes eyestrain. The recommended illumination level for computer workstations is 28 to 50 ft-c. Too much contrast between the task items and the surrounding areas can also stress the eyes. Therefore, the illuminance between the task items, equipment, horizontal work surface, and surrounding areas should be minimized. Finally, the color and finish of the workstation walls and equipment, as well as the arrangement of the lighting sources, should all be designed to avoid reflective glare on the job task (Figure 14-8).72

FIGURE 14-8 Lighting position considerations for computer workstations. Most of these lighting position principles can be applied to workstations in general. (From Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Working safely with video display terminals, Washington, DC, 1997, US Government Printing Office, available at: www.osha.gov/Publications/osha3092.pdf.)

Tools

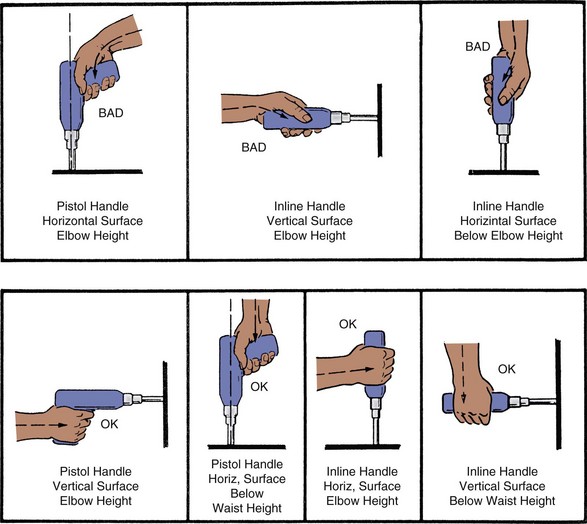

Tools should be designed to protect the worker from hand vibration, extreme temperatures, and soft tissue compression. Therefore, handles on tools are essential. “A properly designed tool handle should isolate the hand from contact with the tool surface, enhance tool control and stability, and serve to increase the mechanical advantage while reducing the amount of required exertion.”81 Since the average worker’s hand is 4 inches (10 cm) across, the length of the tool handle must be at least 4 inches to avoid unnecessary pressure on the palm of the hand. Handles of scissors and pliers should be spring-loaded to avoid trauma to the back and sides of the hands.81

Tool design should minimize muscular effort and awkward posturing of the upper extremity. Whenever possible, opt for power tools to minimize the human effort required. Choose tool shapes that allow the wrist to stay straight and the elbow to stay bent and close to the body during use. The shape of the tool will depend on the job task and work surface (Figure 14-9). Tools that weigh between 10 and 15 lb (4 to 6.5 kg) cannot be held in a horizontal position more than a couple of minutes without the worker experiencing pain and fatigue. Suspension systems and counterweights should be designed for use with heavy hand tools.81

FIGURE 14-9 Hand tool design and wrist posture. (From Armstrong T: An ergonomic guide to carpal tunnel syndrome, Akron, Ohio, 1983, American Industrial Hygiene Association.)

Whole-body vibration can cause back pain and performance problems when the workstation vibrates, as in the case of long-distance truck drivers and in production industries using high-powered drills or saws in the work area.14 Hand-arm vibration has been linked to vascular compromise, peripheral nerve damage, muscular fatigue, bone cysts, and central nervous system disturbances.29 The effects of hand tool vibration should be minimized as much as possible. Use antivibration tools at low speeds when available. Ensure that tool handles and gloves fit the workers’ hands. Train workers to grip tool handles as lightly as possible and allow the tool to do all the work instead of the worker adding force behind the tool. Encourage frequent rest breaks and educate workers that smoking increases the risk for vibration-related hand problems.18,29

Materials Handling

Concerns regarding handling materials center on back injury and include lifting, pushing, pulling, bending, and twisting. The heavier the material, the more risk for injury. Low back injuries are seldom the result of a single traumatic episode but rather the result of repeated microtrauma that ultimately leads to injury.33 Therefore, workstation and work process design becomes integral for the safety of materials handling workers.

Design considerations for heavy lifting include the use of mechanical assist devices whenever feasible (e.g., use of a Hoyer lift for moving immobile patients in the hospital). When mechanical assist devices are not available, training in proper lifting technique and proper body mechanics is important to promote worker safety. Providing workers with back support is controversial, but many believe that the use of an elastic back support “has a preventative function, protecting the tissues … thus making injury less common.”46 Training workers and providing them with back support is only effective, however, when “supervisors and managers encourage the use of safe procedures and write policies that enforce them.”85

The following suggestions are useful for addressing safe handling of materials. Design workstations to keep large items that require lifting off the floor. Provide platforms that will keep items at mid-thigh height to allow workers to stand nearly erect for lifting. Provide foot clearance so that workers can get as close to the item as possible when lifting and face the load head-on. Adjustable lift tables are excellent for this purpose. Objects should be against the torso during the lift to minimize force on the spine. Workers should never be forced to twist their torsos to lift an object. Use carts or conveyors to transport heavy materials instead of carrying them. Orient packages for easy pick-up and provide adequate handles or handhold cutouts on packages.18

As stated earlier, these ergonomic design principles can be applied proactively to work situations to prevent problems before they even occur. For many occupational therapists, however, introduction to ergonomic considerations comes secondarily as part of a comprehensive rehabilitation program for injured workers. Following a work-related injury, ergonomic intervention is essential to the client’s successful re-engagement in the occupation of work. Without the ergonomic intervention aspect, the rehabilitation process cannot be considered complete.

A significant amount of effort goes into the rehabilitation of an injured worker. Physical injuries require the attention of a medical doctor to prescribe rest, medications, and rehabilitative therapies. The occupational therapist will provide acute care of the injuries by fabricating splints, instructing workers in stretching and strengthening exercise, and using physical agent modalities such as heat and ice to calm the soft tissues in preparation for functional rehabilitative activities. Other aspects of the occupational therapy plan include educating the injured worker about the nature of the injury and training in general body mechanics and personal injury management strategies to help prevent recurrence of injury on return to work. In some cases, the injured worker will require specialized conditioning before return to work and will be referred to a work-hardening program.

When the client is ready to return to work, it is important to remember that an injured worker cannot be safely returned to the same job without ergonomic intervention.

It seems obvious that returning an injured worker to the same conditions that caused the injury will certainly result in reinjury if not eliminated before the employee’s return to work. However, ergonomic intervention is sometimes overlooked as an integral part of the rehabilitation program. The goal of ergonomic evaluation and intervention in an injured employee’s work environment is to eliminate factors that contributed to the injury in the first place. If we do not eliminate the major cause of the original injury, it will not be long before the worker suffers a recurrence. If that happens, we have failed as occupational therapists to provide a successful rehabilitation process.

Ergonomic Evaluation

The ergonomic evaluation is an important assessment and intervention tool when used as part of a comprehensive rehabilitation or injury prevention program. This tool can be used along the entire continuum of prevention services. Ergonomic evaluation can be performed during workstation and work methods planning to assist in efforts to prevent worker injury. Ergonomic evaluation can also be performed for workers in whom symptoms of a work-related musculoskeletal disorder (WMSD) develop and for workers who come to therapy for rehabilitation and are ready to return to work, the goal being to prevent reinjury. Finally, ergonomic assessment can be useful in modifying a job in preparation for a disabled worker’s return to work with the goal of preventing further injury related to the disability.

The ergonomic evaluation should begin with the occupational therapist scheduling a time to meet with both the worker(s) to be assessed and the direct supervisor of the work area. The evaluation should be scheduled during the normal work hours of the worker(s). The goal is to obtain the best understanding of what actually occurs during a typical work shift, so the conditions should be closely approximated. It is extremely important that the actual worker(s) be present. The purpose of the evaluation is to look at the fit between the specific worker(s) and the specific job methods, equipment, and set-up. If any element is missing, the evaluation is of little or even no value.

Ideally, the occupational therapist evaluator will arrive at the worksite and meet first with the direct supervisor of the work area to be evaluated. The supervisor will be asked to give an overview of the circumstances leading up to the request for ergonomic evaluation. The occupational therapist will want to know what kinds of injuries are occurring in the work area, when the problem started, and how many employees have been affected. The supervisor will be able to review how the organization has dealt with the problem to date. Frequently, the supervisor will also describe what sorts of psychosocial and environmental influences may be affecting the situation. Occasionally, an ergonomic assessment is requested before any problems occur at all. The supervisor may explain that the employer is just trying to be proactive. In either case, this brief encounter with the supervisor will give an observant occupational therapist evaluator a very good feel for the organization’s management culture and organizational priorities.

Following the supervisor interview, the occupational therapist evaluator will want to see the work area and meet the employees. The supervisor may give the evaluator a brief tour of the work area and describe the job tasks and methods that occur there. If the supervisor has identified any problem areas (areas that the supervisor thinks are contributing to injury), the supervisor should be encouraged to point these out. This part of the evaluation will give the evaluator an understanding of how management views the situation. Next, the evaluator will ask to meet with the workers.

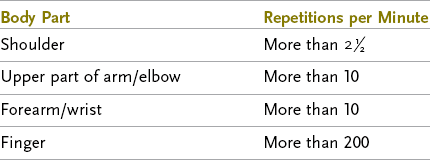

Once alone with the worker(s) it is important to establish some level of trust. The evaluator will explain to the workers(s) why the organization has asked for an ergonomic evaluation. It should be explained that the purpose of the evaluation is to make the job safer and more comfortable for the worker(s). The worker(s) should be encouraged to give the evaluator a tour of the work area and to explain their job tasks. If there are any discrepancies between management’s understanding of the job situation and the workers’ understanding of the same, the evaluator must seek definitive clarification.