Americans With Disabilities Act and Related Laws That Promote Participation in Work, Leisure, and Activities of Daily Living

Americans with Disabilities Act

Individuals not covered by the ADA

Limiting, classifying, or segregating

Contractual relationships that discriminate

Using standards, criteria, and methods of administration that discriminate

Discrimination based on association with an individual with a disability

Failing to make a reasonable accommodation

Employment tests that screen out individuals with disabilities

Administering tests to measure physical attributes, not skills or aptitudes

Retaliating against individuals who file discrimination claims

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

1 Explain how the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) defines disability and how that definition may apply to clients seen by occupational therapists.

2 Compare and contrast definitions of discrimination and discuss how they may apply to clients served by occupational therapy.

3 Recognize and define specific terms used in the ADA, Fair Housing Act, and Air Carrier Access Act.

4 Discuss the roles that occupational therapy can play in advocating for clients under the ADA, Fair Housing Act, and Air Carrier Access Act.

5 Discuss the roles that occupational therapy can play in consulting with employers, places of public accommodation, airline carriers, and landlords.

6 Explain the process used to determine essential job function.

7 Analyze reasonable accommodations as an intervention strategy in occupational therapy and explain the decision-making process involved in making reasonable accommodations.

8 Outline the process for removing physical and other barriers to access to places of public accommodation and the steps necessary to perform an accessibility audit.

9 Prepare and train employers, coworkers, supervisors, airline employees, and those who work with the public to treat individuals with disabilities with dignity and respect.

Americans With Disabilities Act

To understand the protection that the ADA affords Carlotta and the roles that the ADA provides for OTs and occupational therapy assistants (OTAs), one must first have a basic understanding of the ADA, its definitions, and how the courts have interpreted the law. Congress passed the ADA in 1990 in an effort to decrease discrimination against individuals with disabilities and promote their inclusion in the mainstream of society. The law’s antidiscrimination provisions cover employment, certain state and local government services, public accommodations, communications, and public transportation. This chapter explores Title I (employment), Title II (state and local government services), and Title III (public accommodations) and how they affect occupational therapy practice.

Title I: Employment

Before the ADA became law, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 prohibited discrimination against qualified individuals with disabilities in employment by three categories of employers: (1) the federal government, (2) employers who contract with the federal government to provide goods and service, and (3) employers who were recipients or beneficiaries of federal funding.100

Congress extended that protection by expanding it to private employers who are not dependent on federal funding by passing the ADA in 1990. Because one of Carlotta’s concerns is her work and whether she can continue to participate in her work from a wheelchair, knowledge of Title I of the ADA can provide a foundation for occupational therapy intervention.

Title I of the ADA prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in employment with private, nongovernment employers who have 15 or more employees. In a nutshell, the prohibition against discrimination in Title I states:

No covered entity shall discriminate against a qualified individual on the basis of disability in regard to job application procedures, the hiring, advancement, or discharge of employees, employee compensation, job training, and other terms, conditions, and privileges of employment (42 U.S.C. 12112(a)).74

To understand this statement, one must understand the terms used by answering the following questions:

• Who is considered “an individual with a disability” under the ADA?

• What is a “qualified individual with a disability” under the ADA?

The ADA refers to “individuals with disabilities” as opposed to “disabled individuals” to give voice to politically correct terminology that stresses the individual first, not the disability. It defines the phrase “individual with a disability” broadly under three umbrella categories.

Changes in the ADA

When Congress passed the original ADA, it intended to create an inclusive society in which people with disabilities would work, engage in everyday community activities, and benefit from state and local benefits and services side by side and on the same basis as people without disabilities.79 Looking back on the 20th anniversary of the ADA, individuals with disabilities have achieved success in access to participation in the community and government benefits and services.

Employment under Title I proved to be the biggest disappointment with the ADA. Greeted with great fanfare by the disability community, the courts took a civil rights bill intended to provide employment rights for people with disabilities and decimated its intent. Though originally given a broad mandate by Congress and intended to cover all who fit within the definition of “individual with a disability,” the Supreme Court and lower courts acting under its mandate chipped away at these protections and narrowed the definition of “individuals with a disability.”

Ruling on three cases in 1 day, the Supreme Court severely restricted protection for individuals with disabilities in the employment arena.78 For example, the Supreme Court ruled that individuals were not considered persons with disabilities if they used ameliorative measures to decrease the impact of their disabling condition.98 The lower courts interpreted this to mean that someone with diabetes who took insulin was not considered a person with a disability.91

In McClure v. General Motors Corp., 75 Fed. Appx. 983 (5th Cir. 2003), the court held that Mr. McClure’s fascioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, which prevented him from lifting his arms above his shoulders and required him to use an accommodation to perform his job as a mechanic, did not make him a person with a disability. The court stated, “But the evidence [of limitations from his fascioscapulo-humeral muscular dystrophy] does not show that these differences rise to the level of severe restrictions.” Like Carlotta, Mr. McClure had many adaptive devices that “ameliorated the effects” of his disability and its impact on everyday activities.96

The lower courts interpreted the Supreme Court’s restrictions to impose significant restrictions on individuals with intellectual disabilities as well. In Littleton v. Wal-Mart, No. 05-12770 (11th Cir. 2007), Mr. Littleton had an intellectual disability and, with the assistance of a job coach, went for an interview with Wal-Mart for a shopping cart attendant position. Although arrangements were made in advance for the job coach to attend the interview, when they arrived for the interview, Wal-Mart would not allow the job coach to attend the interview. Mr. Littleton did not get the job. The court acknowledged that Mr. Littleton had an intellectual disability, which it referred to as “mental retardation.” In denying Mr. Littleton a trial and declaring that he was not an individual with a disability, the court said in its opinion, “he has pointed to no evidence which would create a genuine issue of material fact regarding whether he was substantially limited in the major life activity of learning because of his mental retardation[now referred to as intellectual disability].”95

The court also said that episodic conditions, such as epilepsy, did not qualify as a disability. For example, in Todd v. Academy Corp., 57 F. Supp 2d 448 (S.D. Tex. 1999), the court found that Mr. Todd was not an individual with a disability because the effects of his seizures were not substantial since they lasted “only” 10 to 15 seconds and did not occur frequently enough.103 In EEOC v. Sara Lee, 237 F. 3d 349 (4th Cir. 2001), the court held that the employee was not entitled to a reasonable accommodation from the employer because the employee took medications for seizures and therefore was not a person with a disability.90

The U.S. Supreme Court further limited the rights of people with disabilities when it reviewed what it means to be “substantially limited in a major life activity” in the case of Williams v. Toyota Motor Mfg.109 Mrs. Williams had tendinitis and cumulative trauma syndrome. The court declared that people with disabilities had to have multiple limitations in their everyday activities to be considered a person with a disability; one limitation was not enough.109

As a result of these decisions, the ADA faded into a hollow promise for people with disabilities in employment. Its definitions are meaningless. Its safeguards no longer provide protection for people with any disability. Veterans returning from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan with limb loss feared that employers could discriminate against them and that the courts would not stand behind them because of the mitigating affect of their prostheses. Carlotta could have found herself without the ADA’s protection because her wheelchair and adaptive aids mitigated the impact of her arthritis.

The disability advocacy community lobbied Congress to change the law to restore Congress’ original intent to ensure that people with disabilities could work and not face unnecessary discrimination. These efforts led to the passage of the ADA Amendments Act (ADAAA), which specifically rejects the Supreme Court’s decisions and broadens the definitions portion of the ADA to return the law to its original intent: a broad scope of protection under the ADA.74 It also extended all of its changes to the Rehabilitation Act of 1973.80

The first definition states that with reference to individuals, disability means “(i) A physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of the major life activities of such individual.”41 A physical or mental impairment includes “any physiological disorder or condition, cosmetic disfigurement or anatomical loss affecting one or more of the following body systems: neurological, musculoskeletal, special sense organs, respiratory (including speech organs), cardiovascular, reproductive, digestive, genito-urinary, hemic and lymphatic, skin, and endocrine.”44 Physical or mental impairment as defined includes most of the traditional medical diagnoses that OTs treat, including, for example, individuals with multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, cerebral vascular accident, and cerebral palsy, as well as Carlotta’s arthritis, which affects the musculoskeletal system. Mental or psychologic impairments include “any mental or psychological disorder, such as an intellectual disability [formerly termed ‘mental retardation’], organic brain syndrome, emotional or mental illness, and specific learning disabilities.”45

The ADAAA broadened the meaning of the phrase “substantially limits” based on Congress’ finding that the former regulation that defined “substantially limited” to mean “significantly restricted” was inconsistent with congressional intent because the standard was too high.81 The ADAAA specified that the term “substantially limits” be interpreted consistently with the findings and purposes of the ADAAA enacted in 2008.82

The implementing regulations incorporated the policies that Congress outlined in the ADAAA into a series of rules to help define “substantially limiting.” The closest one to an actual definition states:

An impairment is a disability within the meaning of this section if it substantially limits the ability of an individual to perform a major life activity as compared to most people in the general population. An impairment need not prevent, or significantly or severely restrict, the individual from performing a major life activity in order to be considered substantially limiting. Nonetheless, not every impairment will constitute a disability within the meaning of this section.48

The remaining rules explain how to interpret this general rule. As Congress intended, the rule shall be interpreted “broadly in favor of expansive coverage” so that people like Carlotta are covered by the ADA.48 Furthermore, lawsuits brought under the ADA should focus on whether employers “complied with their obligations and whether discrimination has occurred, not whether an individual’s impairment substantially limits a major life activity.” Accordingly, the threshold issue of whether an impairment “substantially limits” a major life activity should not demand extensive analysis.48

At the same time, the regulations say that the “determination of whether an impairment substantially limits a major life activity requires an individualized assessment.”47 This is an area where OTs can provide some consultation. If Carlotta needed to prove that she was an individual with a disability, the OT can help provide the individualized assessment of her disability and contribute the major life activities limited by Carlotta’s arthritis to the process. The regulations reiterate that the standard used for this assessment is lower than the previous “substantially limited” standard.47

The regulations also say that the “comparison of an individual’s performance of a major life activity to the performance of the same major life activity by most people in the general population usually will not require scientific, medical, or statistical analysis.”49 However, an individual with a disability, like Carlotta, could present “scientific, medical, or statistical evidence” to show the comparison, which could include evidence from an occupational therapy assessment.49

The other rules governing “substantially limited” incorporated the specific concerns that Congress expressed in the law to address the problems created by the Supreme Court cases: mitigating measure, impairment that is episodic or in remission, and impairment in only one major life activity. The ameliorative effects of mitigating measures will no longer play a role in the determination of whether an impairment substantially limits a major life activity.50 Congress specified examples of mitigating measures as follows:

1. “medication, medical supplies, equipment, or appliances, low-vision devices (which do not include ordinary eyeglasses or contact lenses), prosthetics including limbs and devices, hearing aids and cochlear implants or other implantable hearing devices, mobility devices, or oxygen therapy equipment and supplies”

2. “use of assistive technology”

3. “reasonable accommodations or auxiliary aids or services” or

4. “learned behavioral or adaptive neurological modifications.”82

An episodic impairment or one that is in remission is considered “disability if it would substantially limit a major life activity when active.”51 An impairment need limit only one major life activity to be considered a substantially limiting impairment.52 For Carlotta, this means that none of the following circumstance—her use of assistive technology, a limitation only in walking, and remission of her arthritis—would prevent her from qualifying as substantially limited or a person with a disability.

Major life activities include many areas of occupation and related activities of daily living (ADLs) functions, including “but…not limited to, caring for oneself, performing manual tasks, seeing, hearing, eating, sleeping, walking, standing, sitting, reaching, lifting, bending, speaking, breathing, learning, reading, concentrating, thinking, communicating, interacting with others, and working.”46 Another category of major life activities includes “operation of a major bodily function, including functions of the immune system, special sense organs and skin; normal cell growth; and digestive, genitourinary, bowel, bladder, neurological, brain, respiratory, circulatory, cardiovascular, endocrine, hemic, lymphatic, musculoskeletal, and reproductive functions. The operation of a major bodily function includes the operation of an individual organ within a body system.”46

Sometimes, when determining whether a person is limited in a major life activity, one may want to look at the condition under which individuals perform the activities, the manner in which they perform them, and/or how long it takes individuals to perform them.48 However, the regulations give examples of certain disabilities that one could easily conclude will substantially limit at least the major life activity indicated in Box 15-1.

The occupational therapy evaluation provides the information that the court will want to use to make a determination whether an individual is substantially limited in major life activities. OTs may find themselves assisting employers, attorneys, and others by providing this information, if requested.

The occupational therapy evaluation of Carlotta shows that she has arthritis, which substantially limits the major life activity of walking. Carlotta’s arthritis also substantially limits her musculoskeletal function. She has difficulty participating in or is unable to participate in a variety of tasks related to everyday living. In light of these limitations, she probably falls under the first definition of disability.

The second definition of an individual with a disability under the ADA includes someone who has a record of having had such an impairment as described in the first definition.42 This category includes persons with a history of a disabling condition, such as an individual who had multiple sclerosis that is now in remission or someone cured of hepatitis C.

The third definition of an individual with a disability includes situations in which someone is regarded as having a substantially limiting impairment that is a perception of a disability based on myths, misperceptions, fears, and stereotypes.43 For example, suppose a morbidly obese individual, Sue, seeks a promotion to a position that requires frequent trips out of town. The person empowered to decide whether Sue gets that promotion assumes that Sue will have difficulty managing the traveling because of her size. The manager is concerned that Sue will struggle with walking through the airports, breathing, and other nonsedentary aspects of her job. Sue has had a perfect attendance record and has always received excellent performance appraisals. The manager bases his failure to hire Sue on his assumptions about her supposed difficulty walking, breathing, and completing nonsedentary tasks, and these assumptions are simply not true. The manager regards Sue as being an individual with a substantially limiting impairment.

Individuals Not Covered by the ADA

The ADA provides its protection against disability discrimination only for those who meet the criteria outlined earlier. This means that individuals with temporary impairments, such as a broken leg or after a knee replacement that is likely or expected to heal normally, will not find that the ADA protects them. Individuals who have impairments that are not substantially limiting, such as a visual limitation correctable with eyeglasses, will not find benefits under the ADA.

Furthermore, the ADA enumerates specific exclusions in its definition of disability. The ADA does not provide protection for individuals who fall into one of the following categories: transvestites, homosexuals, pedophiles, exhibitionists, voyeurs, gender disorders not caused by physical impairments, and other sexual behavior disorders.63 The ADA further excludes from its protection illegal drug users, compulsive gamblers, kleptomaniacs, pyromaniacs, and alcoholics whose alcohol use prevents them from performing their jobs.64 The ADA does provide protection against discrimination based on disability for recovering illegal drug users, as long as they participate in a rehabilitation program.

Qualified Individuals

Title I of the ADA does not protect all individuals with disabilities. It protects only those who are qualified individuals with a disability. The ADA specifies that “the term ‘qualified,’ with respect to an individual with a disability, means that the individual satisfies the requisite skill, experience, education and other job-related requirements of the employment position such individual holds or desires and, with or without reasonable accommodation, can perform the essential functions of such position.”53 The first inquiry in deciding whether an individual with a disability meets the basic job requirements looks at individuals’ amount of experience, level of education, and skills necessary to perform the job. Carlotta meets these requirements since the school hired her as a qualified teacher more than 18 years ago, and thus she meets the basic education, skills, and experience requirement. The next inquiry is whether the individual in question can perform the essential functions of the job.

Essential Job Functions

The ADA defines essential job functions as job duties fundamental to the position that the individual holds or desires to hold, as opposed to functions that are marginal functions.54 Essential functions are those that the individual who holds the position must be able to perform with or without the assistance of a reasonable accommodation. One may consider a function essential because the position exists to perform the particular function. These essential functions are usually obvious. For example, a typist must type and a proofreader must proofread.

A function is essential because of the limited number of employees available who can share the particular function. For example, because there are only three Spanish teachers at Carlotta’s school, Carlotta must collaborate with the other two Spanish teachers to write and direct the annual Spanish language pageant. If the school employed 20 Spanish teachers, responsibilities may be divided so that Carlotta did not have to participate in the annual Spanish language pageant.

An essential function is also one in which the function is so specialized that the employer hires the person in the position for his or her particular expertise or ability to perform that function. For example, a brain surgeon is a highly specialized position, and the person in this position is hired to perform highly technical surgery.

Whether a function is an essential function is determined on a case-by-case basis. Specific evidence will support whether a particular function is essential. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the federal agency that provides enforcement of Title I’s provisions, and the courts will look at seven factors55 as evidence of whether a function is essential (Box 15-2).

In some situations essential functions are obvious. For example, the essential functions of a receptionist’s position may include answering telephones, taking messages, and greeting and announcing visitors. Typing may be a marginal function for a receptionist in a very busy office where the receptionist has not had to type anything at all over the last 6 months. One determines essential job functions on a case-by-case basis by looking at the facts of each situation. OTs can help determine essential job functions by looking at the job description, by conducting focus groups with employees, and by performing a job analysis as discussed in Chapter 14.

In determining essential job functions, the focus must be on the outcome or job tasks that employers expect employees to perform. The definition of essential job functions focuses on the concept of job duties or expected outcomes, not the physical demands required to perform a job duty. In other words, an essential function is a task that one must perform to perform the job, not a physical function. Essential functions are not bending, lifting, walking, climbing, or other physical demands. For example, a mail clerk for a large corporation includes delivering mail as one of his essential functions. The essential function is not walking and carrying the mail but rather the outcome of delivering the mail. If the mail clerk were not able to carry the mail, he could push the mail on a cart to accomplish the same result or outcome. Essential functions are what you do, not how you do it.

The job description, job analysis, and discussions with Carlotta about her job show that as a teacher, Carlotta must perform several essential functions, including grading papers and tests and recording their results, discussing student progress with parents, preparing lesson plans, motivating students, and maintaining order in the classroom. (Note that these essential functions are all specific job tasks and not physical functions such as “hand manipulation skills for writing” or “walking around the classroom.”) The occupational therapy evaluation shows that Carlotta is able to perform these functions for her position as a Spanish teacher. However, she may have difficulty maneuvering around the classroom to the desks of the individual students because of steps and multiple levels in the former band classroom in which she currently teaches Spanish. Carlotta will also have difficulty writing on the blackboard from a wheelchair. The key to facilitating Carlotta’s continued participation in the workplace lies in making reasonable accommodations.

Reasonable Accommodations

The ADA defines reasonable accommodations as any change in the work environment or in the way that work is customarily performed that enables an individual with a disability to enjoy equal employment opportunity.56 Not all employees are entitled to reasonable accommodation. Employers need to make reasonable accommodations only for employees with disabilities who are qualified (Box 15-3).

Reasonable accommodations include three subcategories. First, reasonable accommodations include modifications or adjustments in the job application process that enable consideration of a qualified applicant with a disability for employment in a position that the person wants.57 This would include reading a job application to an individual with dyslexia or modifying the way that a preplacement screening is performed to accommodate an individual with one hand. If Carlotta were to apply for another position, her potential employer would need to provide her with an accessible entrance to the human resources department so that she could obtain a job application.

The potential employer would also have to allow her to use a larger pen for filling out an application because she uses the larger pen to prevent joint changes in her hand. As an alternative, the potential employer can provide someone to assist her in filling out the application.

The modifications and adaptations that OTs most typically provide fall under the umbrella of the second category of reasonable accommodations. The second category includes modifications or adjustments to the work environment or to the manner or circumstances in which the position is customarily performed to enable an individual with a disability who is qualified to perform the essential functions of that position.58 OTs have traditionally been involved in this area by modifying job sites, including raising or lowering work heights, making a jig, or using a piece of equipment such as a cart to move objects rather than carrying them.

Carlotta’s continued participation in her work environment will require reasonable accommodations in her intervention plan in the form of changes in the way that the work is performed. For example, Carlotta’s employer could reasonably accommodate her by moving Carlotta to a different classroom—one that is all on one level and without steps or risers throughout the room to provide physical access to the students at their desks. Carlotta could also benefit from a laptop computer with a projector that has a liquid crystal display (LCD), which will eliminate the need for her to write on the board—an impossible task from a wheelchair level. (See Chapter 14 for more detailed discussion of job modifications.)

OTs and OTAs working on the development of reasonable accommodations should note that employers must provide an effective reasonable accommodation, which means one that works, not the most expensive accommodation or the specific accommodation that the employee wants. Although the employee suggests the specific type of accommodation, ultimately, the employer gets to select the accommodation used. If a shoebox with some rubber bands wrapped around it works as well as the high-tech computerized gadget that the employee requests, the employer need only provide the shoebox.

The third category of reasonable accommodations includes modifications or adjustments that enable employees with a disability to enjoy equal benefits and privileges of employment as other similarly situated employees without disabilities enjoy.59 For example, suppose the language department at Carlotta’s school customarily holds an annual international fair for all of the students and their families at the school. The teachers compete by class for the best food, costumes, and projects. The teacher of the winning class wins prizes supplied by the Parent-Teacher Association (PTA). Under the ADA, the school would be required to hold the fair at an accessible location so that Carlotta could participate. This would also apply to the school’s annual holiday party and all other school functions for employees. OTs can improve awareness by employers, assist them in making reasonable accommodations, and help sensitize employers to the needs of individuals with disabilities in these situations.

According to the ADA, reasonable accommodations may include physical changes to make facilities accessible, in addition to other nonenvironmental changes. Depending on the individual circumstances, reasonable accommodations can include job restructuring, part-time or modified work schedules, reassignment to a vacant position, acquisition or modification of equipment or devices (such as Carlotta’s laptop computer and LCD projector), appropriate adjustment or modification of examinations, training materials or policies, provision of qualified readers or interpreters, and other similar accommodations for individuals with disabilities.57,58

For example, an individual who needs to begin kidney dialysis may find that leaving work early 3 days a week reasonably accommodates his needs. Allowing a cashier with fatigue from multiple sclerosis to sit instead of stand while working may reasonably accommodate her needs. Because of their knowledge of the limitations of impairments and how to adapt the work environment to the individual, OTs can suggest and/or design many of these accommodations while working together with the client. Carlotta has a good understanding of much of what she needs to reasonably accommodate her work needs, and her intervention plan should incorporate her insights and suggestions.

The most efficient way for employers to identify the reasonable accommodations that an individual employee may need is to initiate an informal, interactive process with the qualified individual with a disability in need of the accommodation.84 Employers will find that individuals with a disability are often in the best position to determine which reasonable accommodations that they may need to enable job performance. OTs may participate in this effort when the parties need additional expertise to make these accommodations. The EEOC, the federal government agency charged with enforcing the ADA, recognizes the expertise of OTs in assisting to make reasonable accommodations.88

The ADA provides an exception to the employer’s requirement to provide reasonable accommodations for qualified individuals with disabilities. Employers need not provide reasonable accommodations when provision of the accommodation would cause an undue hardship to the employer. Undue hardship refers to any accommodation that would be unduly costly, extensive, substantial, or disruptive or that would fundamentally alter the nature or operation of the business.60 For example, it would probably be an undue hardship for the school to fix Carlotta’s classroom by ripping out the floor in the old band room to remove the risers and level the floor because it would eliminate the use of a very needed classroom for an extended period and might represent a significant expense. The alternative, to swap classrooms with another teacher, would be more cost-effective and less disruptive.

Determination of whether an accommodation presents an undue hardship to the employer involves looking at whether the proposed action requires significant difficulty or expense when the following factors are considered61:

• Nature and cost of the accommodation needed in light of tax credits and deductions and/or outside funding

• Overall financial resources of the facility, the number of persons employed at the facility, and the effect on expenses and resources

• Overall financial resources, overall size of the business, and the number, type, and location of facilities

• Composition, structure, and functions of the workforce

• Impact of the accommodation on operation of the facility, including impact on the ability of other employees to perform their duties and impact on the facility’s ability to conduct business

According to the Job Accommodations Network, a federally funded program that has provided technical assistance in making accommodations for more than 25 years, data show that more than 50% of all accommodations cost nothing. Furthermore, its statistics also show that employers experience financial gains from the decreased costs of training new employees, a decrease in insurance costs, and an increase in worker productivity.93

Discrimination under the ADA

The ADA does not give one specific definition of discrimination. Instead, it specifies at least nine categories of activities considered discriminatory.

Limiting, Classifying, or Segregating: The first prohibited activity includes limiting, classifying, or segregating the employee because of his or her disability.65 For example, if Carlotta’s school were to require all employees who use wheelchairs for mobility to work in one wing of the first floor, it would be segregating the employees with disabilities. This section also forbids employers from asking any questions about an applicant’s worker’s compensation history during the interview or on the employment application since employers can use this information to limit or classify individuals because of their disability.

Poor disability etiquette can lead to limiting, classifying, and segregating individuals with disabilities in the workplace. The way that coworkers treat people with disabilities and the language that they use to refer to individual with disabilities can also make people feel bad or left out of the workplace culture. One method that employers may use to avoid limiting, classifying, or segregating employees because of their disabilities is to sensitize supervisors and other employees to working with individuals with disabilities. Nondisabled individuals who lack familiarity in socializing with individuals with disabilities may not know how to shake hands with a person who does not have a right hand. They may shout at a person who is deaf instead of speaking clearly and facing the person with the hearing impairment.

OTs can work with supervisors and coworkers on basic disability etiquette tips such as using politically correct terminology in which, as mentioned earlier, the person comes before the disability. For example, using the phrase “a person who had a stroke” is better than calling someone a “stroke patient” or “stroke victim” because the word victim has negative connotations. Using the phrase “wheelchair user” is more appropriate than “wheelchair bound” because no one is physically bound to the wheelchair as a book is bound to its binding. Box 15-4 gives more tips on disability etiquette. For tips on conducting the interview process, see Box 15-5.

Contractual Relationships That Discriminate: The second prohibited activity includes participating in a contractual or other relationship that results in discrimination against qualified applicants or employees because of their disability.66 This provision applies to collective bargaining agreements, contracts with employment agencies, and other contracts. For example, suppose Carlotta’s employer contracted with an outside company to provide continuing education courses at her school. The continuing education company would have to comply with the ADA by offering reasonable accommodations when needed, such as allowing Carlotta to tape sessions or providing her with a note taker if she is unable to take notes during the classes. The OT could work with the continuing education provider to help develop other reasonable accommodations for Carlotta and other individuals with disabilities.

Using Standards, Criteria, and Methods of Administration That Discriminate: The third prohibited activity includes the use of standards, criteria, or methods of administration that are not job related and consistent with business necessity and have the effect of discrimination based on the disability.67 For example, an employer could not require that Carlotta possess a driver’s license for promotion to Chair of the Spanish Department if driving is not an essential function of the position.

Employers may use a direct threat standard to exclude from employment individuals whose disabilities pose a direct threat to the health and safety of themselves or others in the workplace.62 However, the direct threat must pose a significant risk for substantial harm to the health or safety of the individual or others that employers or others cannot eliminate or reduce to less than a significant risk by reasonable accommodation. Employers must consider the duration of the risk, the nature and severity of the potential harm, the likelihood that the potential harm will occur, and the imminence of the potential harm.62

For example, suppose Carlotta wanted to swap classrooms with a teacher whose classroom is on the second floor of the school, which has three stories and an elevator. The headmaster could not refuse to allow Carlotta to use this second-floor classroom because he fears that Carlotta, as a wheelchair user, would pose a direct threat in the event of a fire. The chance of a fire occurring is small; therefore, little likelihood exists that any harm will occur. Moreover, the school could develop an emergency plan in advance that would further lower the risk.

Employers must base the determination that an individual poses a direct threat on an individualized assessment of the person’s present ability to safely perform the essential functions of the job. Employers must base the assessment on a reasonable medical judgment that relies on the most current medical knowledge and/or on the best available objective evidence.62

The regulations suggest that employers seek opinions from professionals who have expertise in the disability involved or direct knowledge of the individual with the disability. The EEOC recognizes that documentation of direct threat can come from OTs “who have expertise in the disability involved and/or direct knowledge of the individual with a disability.”88 Often, a reasonable accommodation can reduce the risk. For example, a teenager with epilepsy has a seizure every time that the buzzer goes off on the french fryer while working at the local fast-food restaurant. The OT suggests that the employer could reasonably accommodate him by changing the buzzer to a bell.

Discrimination Based on Association with an Individual with a Disability: The fourth prohibited activity includes excluding or otherwise denying equal job or benefits to a qualified individual because of a disability identified in an individual with whom the qualified individual is known to have a family, business, social, or other relationship or association.68 For example, an employer could not refuse to hire Carlotta’s husband because Carlotta has arthritis and is in a wheelchair and the employer is worried that Carlotta’s husband may have excessive absences because of Carlotta’s condition. In fact, this principle prohibits the employer from asking any questions that may reveal information about his wife’s disability.

Failing to Make a Reasonable Accommodation: The fifth prohibited activity includes failing to make a reasonable accommodation after a request for a particular accommodation for a known disability of a qualified individual or denying someone employment to avoid providing a reasonable accommodation, unless the employer can show that the accommodation would impose undue hardship on operation of the business.69 As discussed previously, the OT can play a major role in assisting employers to determine reasonable accommodations. As mentioned earlier, Carlotta’s intervention plan includes her need for the following reasonable accommodations: a laptop computer with an LCD projector and a one-level classroom. Carlotta must request the specific accommodations that she wants. As part of the intervention plan, the OT may prepare a report as documentation to the school explaining Carlotta’s need for the particular accommodations for submission with Carlotta’s accommodation request. The OT may meet with the school to help staff members understand the needed accommodations. Should Carlotta’s school fail to make the reasonable accommodations that she requests, it would violate this provision of the ADA.

The employer must know that a prospective or actual employee is an individual with a disability before its obligation to make accommodations arises. Courts have found that an employer cannot discriminate based on disability if it does not know about the disability (Morisky v. Broward County).97 Vague statements about one’s limitations or past are not sufficient to put the employer on notice of a disability.97 Disabilities such as multiple sclerosis, arthritis, learning disabilities, and mental health disorders may not be as obvious to an employer as seeing someone in a wheelchair. For employees to obtain reasonable accommodations for these hidden disabilities, employees or potential employees must disclose their disability to the employer. OTs can work with clients as employees or potential employees in determining whether to disclose the disability, when to disclose it, and how to disclose it.

Employment Tests That Screen Out Individuals with Disabilities: The sixth prohibited activity involves using employment tests that tend to screen out individuals with disabilities on the basis of their disability, unless the test is shown to be job related for the position in question and is consistent with business necessity.70 The EEOC considers a test job related if it measures a legitimate qualification for the specific job in question.88 A test is not consistent with business necessity if it excludes an individual with a disability because of the disability and is not related to the essential functions of the job.88 For example, under this section of Title I, the private school where Carlotta works could not give a written, twelfth grade–level reading test to an individual with a known learning disability who applies for a janitorial position. The janitorial position requires reading labels, which are on a fourth grade reading level. That test would screen out the applicant based on her disability and is neither job related nor consistent with business necessity.

Administering Tests to Measure Physical Attributes, Not Skills or Aptitudes: The seventh prohibited activity involves failing to administer tests in a manner to ensure that when administered to a job applicant or employee with a disability that impairs sensory, manual, or speaking skills, the test results accurately reflect the skill, aptitude, or whatever other factor of the applicant or employee that the test purports to measure rather than the sensory, manual, or speaking skills, except when such skills are the factors that the test purports to measure.71 For example, in Stutts v. Freeman,102 an individual with dyslexia was denied a heavy equipment job because he could not pass the written test required to enter a training program. The standard that he pass a written test had the effect of discriminating against the plaintiff as a result of his disability because the test was not meant to test the applicant’s ability to read and write but rather his knowledge of heavy equipment operation. Had the employer administered the test orally, the potential employer would have focused on evaluation of the applicant’s qualifications for the job, not his ability to read the material.

Retaliating against Individuals Who File Discrimination Claims: The eighth prohibited activity prevents employers from retaliating against individuals who file claims for discrimination under Title I.72 Before an applicant can file a lawsuit in court under Title I, he or she must file a complaint with the EEOC. This section prohibits an employer from firing, demoting, or otherwise retaliating against an employee who files a charge of discrimination with the EEOC or otherwise pursues his or her rights under this law.

Conducting Pre-employment Medical Exams or Inquiries: The final prohibited activity keeps employers from conducting pre-employment medical examinations of an applicant or employee or inquiring into whether the applicant is an individual with a disability or the nature and extent of the person’s disability before the employer extends an offer of employment to the applicant.73 Under the ADA, a medical examination means a “procedure or test that seeks information about an individual’s physical or mental impairments or health.”89 The EEOC considers a variety of factors in deciding whether a test is a medical exam. These factors include, among others, whether the test is administered or the results interpreted by a health care professional or someone trained by a health professional, whether the test is designed to reveal an impairment, and whether the test measures the applicant’s performance of a task or his or her physiologic responses to performing the task.89

Preplacement Screenings and Functional Capacity Assessments

This provision of Title I affects the way that OTs do business. OTs are often involved in preplacement screenings and functional capacity evaluations, which are sometimes considered under the category of fitness-for-duty exams. Employers often hire OTs to perform these tests, which are described more fully in Chapter 14. The ADA regulations outline the types of testing that employers (or those acting on their behalf) may perform and the stages at which they may perform them.

The hiring process includes two relevant stages. The first stage, the pre-offer, occurs during the interview process, before an employer extends an offer of employment to an applicant or candidate. The second stage, the post-offer, occurs after the employer has made a hiring decision and extends an offer of employment to the applicant or candidate. We often speak of this offer of employment as a conditional offer of employment because it is subject to withdrawal under certain circumstances, which this chapter addresses later.

During the pre-offer stage, an employer may conduct only a simple agility test. Employers and OTs acting on their behalf may not conduct medical examinations or inquiries, pre-employment physical examinations, pre-placement screening, or functional capacity assessments during the pre-offer stage. An agility test is a simple test that looks at one’s physical agility. It is not a medical test. Agility tests do not involve medical examinations, physicians, or medical diagnoses. Employers may request clearance from the applicant’s physician before administering an agility test.88 The classic agility test for police recruits shows them running through tires, scaling a wall, and climbing ropes. Another example of a permissible agility test would include an employer asking an applicant to carry a piece of wallboard from one end of the construction site to the other.

Although employers may conduct these agility tests, ADA rules govern their use. If an employer chooses to use an agility test, it must give the test to all similarly situated applicants or employees. If the agility test screens out individuals with disabilities, the employer must show that the test is job related, consistent with business necessity, and that the applicant could not perform the job with a reasonable accommodation.

During the post-offer stage, employers or those acting on their behalf may conduct agility tests, medical exams and inquiries, pre-employment physicals, preplacement screenings, and functional capacity assessments. If the employer chooses to give medical exams once it makes a conditional offer of employment, it must give the exam to all employees entering the same job category. The ADA does not require that a medical exam satisfy the job-related and consistent-with-business-necessity standards. However, if the employer withdraws a conditional offer of employment because of the results of the medical exam, the employer must be able to show the following: (1) the reasons for the exclusion are job related and consistent with necessity or the person is being excluded to avoid a direct threat to health or safety and (2) no reasonable accommodation was available that would enable this person to perform the essential functions without a significant risk to health or safety or the accommodation would cause an undue hardship.

As mentioned earlier, during the post-offer stage, employers and OTs acting on their behalf may perform preplacement screenings and functional capacity assessments. Both are subject to the same requirements as medical exams. In other words, although the tests need not comply with the job-related and business-necessity requirements, should the tests screen out individuals with disabilities, job related and business necessity become the required standard to meet. Reality dictates then that to comply with the ADA, the preplacement screening must be job related and test only the essential functions of the job. For example, assessing Carlotta’s hand strength as a part of the interview process for hiring her as a Spanish teacher would violate this provision of the ADA because hand strength is not job related and not related to an essential job function.

Employers and those acting on their behalf must keep the results of all medical exams and inquiries confidential with some limited exceptions. These exceptions include work restrictions information, insurance purposes, government investigations of ADA complaints, and state worker’s compensation and second injury funds, which are funds set up by some states to encourage employers to hire individuals with previous workers’ compensation–related or other injuries.

This prohibition against inquiries into medical and disability-related information also extends to job applications and interviews. Employers cannot ask questions about someone’s disability or questions that will lead to information about someone’s disability during the job interview process. Box 15-6 shows examples of questions that employers cannot ask during the interview process.

OTs can assist human resources professionals in the proper way to inquire into an individual’s ability to perform the essential functions of a position without asking prohibited questions. Employers must base their interview questions on specific job functions, information that OTs gather from the job analysis described in more detail in Chapter 14. Ideally, the interviewer should have a job description prepared from the OT’s job analysis and ask interviewees questions about the match between their skills and abilities and the job’s essential functions.

The Role of the Occupational Therapist

OTs can work together with individuals with disabilities as part of their intervention plans to identify needed accommodations that will enable participation in the workplace and plan a strategy to obtain those accommodations from the employer. OTs can help their clients understand their right to reasonable accommodations under Title I of the ADA. This includes the need to request the specific accommodations needed and to furnish documentation of the need, which the OT can prepare for the client’s submission to the employer. OTs may find themselves advocating for the accommodations to their clients’ employer.

For example, as described earlier, Carlotta’s OT can play a major role in her employer’s provision of the accommodations that she needs. Carlotta and her OT identified the accommodations that she needs as part of her occupational profile and intervention plan. If the employer refuses to provide the accommodations after Carlotta provides the OT’s documentation and if Carlotta eventually files a lawsuit, the OT may find himself or herself testifying in court about Carlotta’s need for the accommodations.

OTs can also provide consultation services for employers who want to avoid litigation and seek advice on making reasonable accommodations for its employees with disabilities. If Carlotta’s employer were proactive, he may have contacted an OT for advice on how to accommodate Carlotta.

This kind of consultation, in which the client is the employer, not the individual with a disability, usually begins with a job analysis (described in detail in Chapter 14) to see what the job requires. The therapist takes this information, compares it with the individual’s limitations, and tries to develop accommodations to enable performance. This accommodation development stage cannot proceed without input from the person with the disability.

For example, the author was hired by a hospital to look at whether a nurse affected by some post-polio weakness and arthritis could use a scooter (wheelchair substitute–type scooter) as her requested accommodation to cut down on the number of steps that she took during the day. The nurse had filed a charge of discrimination with the EEOC, and the hospital’s attorney suggested hiring an OT to see whether the requested accommodations were reasonable so that it could avoid a full-blown lawsuit. The head nurse could not imagine a nurse using a scooter. The author performed a job analysis and determined that the scooter was a reasonable accommodation. Convincing the head nurse that the scooter was reasonable took more work in the form of sensitivity training, to which the OT also contributes.

Title II: State and Local Government Services

Title II of the ADA prohibits state and local government entities and those with whom they contract from denying a qualified individual with a disability participation in or the benefits of services, programs, or activities that it provides to individuals without disabilities.23 Title II’s antidiscrimination protection in the employment of individuals with disabilities by state governments has been limited by cases decided by the U.S. Supreme Court. Individual state employees can no longer bring lawsuits for monetary damage in federal court when a state discriminates in its employment practices based on the disability.86

Title II’s other requirements look similar to those of Title III, described in detail later for nongovernment entities. However, Title II goes further in its requirement for state and local government services than for privately owned entities in one particular concept.

Title II requires that government agencies give qualified individuals with disabilities equal opportunity to participate in or benefit from the state or local government aid, benefits, or services.24 This requires providing more access than in Title III’s requirements to provide what is readily achievable, as described later in this chapter. Providing equal opportunity to state and local government services requires taking measures such as making facilities physically accessible, making policy changes, providing reasonable accommodations in the form of auxiliary aids and services, providing accessibility in public transportation, and supplying communication aids such as 911 services for the hearing impaired, as well as other accommodations described more fully under Title III later. OTs can help state and local governments make some of the needed changes, as will be discussed further in this chapter.

Title II and Title III were amended through the rule-making process, and new regulations took effect March 15, 2011.105–107 Most of the changes apply to both Title II and Title III. Several are specific to Title II. In particular, residential housing programs and detention and correctional facilities run by state and local governments must now comply with the applicable design requirements listed in the new 2010 Standards for Accessible Design, called “the 2010 Standards.”106,108

Title III: Public Accommodations

Title III of the ADA prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in places of public accommodation (PPAs). One may find this description slightly misleading because despite its name, this section of the ADA covers privately owned entities that own or lease to others, places that affect commerce. In other words, PPAs are privately owned entities where business of some kind is transacted or affected. The term PPA covers 12 broad categories enumerated in the ADA (Table 15-1).25 The U.S. Department of Justice, the federal government agency charged with overseeing and enforcing Title III, reports that more than 5 million PPAs exist in the United States.104

TABLE 15-1

Places of Public Accommodation under Title III

| Category of Public Accommodation | Examples |

| Places of lodging | Hotels, motels |

| Establishments serving food or drink | Restaurants, bars |

| Places of exhibition or entertainment | Movie theaters, stadiums |

| Places of public gathering | Convention centers |

| Sales or rental establishments | Bakeries, shopping malls |

| Service establishments | Laundromats, funeral homes, doctors’ offices |

| Public transportation terminals | Train stations |

| Places of public display or collection | Museums, libraries |

| Places of recreation | Parks, zoos, amusement parks |

| Places of education | Preschools, private schools, colleges |

| Social service establishments | Daycare centers, senior centers |

| Places of exercise or recreation | Health clubs, bowling alleys, golf courses |

The super rule, which forms the basis for Title III, prohibits discrimination as follows:

No individual shall be discriminated against on the basis of disability in the full and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages, or accommodations of any place of public accommodation by any private entity who owns, leases (or leases to), or operates a place of public accommodation.26

Under Title III, PPAs must remove barriers to access, and if it cannot remove the barriers, the PPA must provide an alternative or reasonable accommodation to provide access to the goods and services that it provides. Many think of the barriers that Title III addresses as architectural barriers or barriers in the physical environment, such as steps and curbs, that limit physical access to a place that one desires to go.

Although many view the requirements of Title III as a quasi–building code, removing barriers to access as described in the ADA refers to more than mere access through removal of physical barriers. It also refers to access caused by attitudinal barriers and rules and to policies based on myths, misperceptions, and fears about individuals with disabilities that act as barriers to their access to PPAs.

For example, before the ADA became law, some banks refused to allow individuals who are blind to have safe deposit boxes. The rationale behind this policy asserts that because individuals who are blind cannot see what is in their safe deposit boxes, how can they remove things that they need from the box? Only the safe deposit box holder can go into the viewing booth. Based on misperceptions, banks believed themselves at risk for accusations of theft from the boxes and, as a result, disallowed individuals who were blind from benefiting from the services that they provided to individuals who were not blind. This practice discriminated against individuals with visual impairments. The ADA prohibits these practices and seeks to break down these kinds of barriers.

To further its mission of breaking down physical and attitudinal barriers, Title III specifies three broad principles that provide the foundation for its philosophy of inclusion of individuals with disabilities in society. First, PPAs must provide individuals with disabilities an equal opportunity to participate in or benefit from the goods and services offered.27 Furthermore, PPAs must give individuals with disabilities an equal opportunity to benefit from the goods and services that they offers.27 Finally, PPAs must provide the benefits in the most integrated setting possible.27,28

PPAs can violate Title III’s mandates against discrimination by doing the following, among other things.

• Refusing to admit an individual with a disability merely because he or she has a disability.27 For example, a restaurant cannot refuse to admit and/or serve an individual with cerebral palsy because he or she drools.

• Failing to provide goods and services to individuals with disabilities in the most integrated setting appropriate to the individual’s needs.28 For example, a professional or college football team cannot segregate all wheelchair users in a “handicapped” section in the end zone. It must allow wheelchair users to sit with family members and disperse wheelchair seating throughout the stadium.

• Using eligibility criteria that screen out or tend to screen out individuals with disabilities from full and equal enjoyment of goods and services.30 For example, retail stores located in a busy tourist area require that individuals using credit cards show a driver’s license as proof of identification as a way of cutting down on the use of stolen credit cards. However, this practice screens out individuals with visual impairments or other disabilities who do not qualify for driver’s licenses. The retail stores would have to accept state identification cards in place of a driver’s license from individuals with disabilities who do not qualify for driver’s licenses.

• Failing to make reasonable modifications in policies, practices, or procedures when the modifications are necessary to offer goods, services, or facilities to individuals with disabilities.31 The example given earlier regarding bank policies for safe deposit boxes and individuals who are blind is a good illustration of a policy that discriminates on the basis of disability. As another example, Great Grocery Store has a policy whereby cashiers must place all checks in a specific column in the cash drawer. Carlotta’s OT recommended that she use large-print checks because she can write more legibly with larger print. She attempts to give the cashier a large-print check. The cashier refuses to take the check because it does not fit in the cash drawer column for checks. She also tells Carlotta that their policy is to accept large-print checks only from blind people. Great Grocery Store must modify its policies and accept Carlotta’s check.

• Failing to take steps to ensure that individuals with disabilities are not excluded or denied services, segregated, or otherwise treated differently from individuals without disabilities because of the absence of auxiliary aids and services.33 Auxiliary aids as used in the ADA include devices that OTs usually refer to as adaptive equipment or assistive technology. According to the regulations, auxiliary aids and services include, among other things, qualified interpreters on site or through video remote interpreting (VRI) real-time computer-aided transcription services, assistive listening devices, closed-captioned decoders on televisions, Braille materials, taped texts, and “acquisition or modification of equipment or devices.”33

For example, suppose Carlotta stays at a restored historic hotel in her quest for the perfect bed and breakfast. She finds that she can use the bathing facilities in her room only if she has a tub bench. The hotel would have to provide her with a bathtub bench as an auxiliary aid so that it will not exclude or deny her bathing services.

Two exceptions exist to the auxiliary aid provision requirement. The PPA need not provide an auxiliary aid that fundamentally alters the nature of the goods and services offered or causes an undue burden.33 An undue burden means that provision of the auxiliary aid would cause significant difficulty or expense. The impact on the PPA varies, depending on such elements as the size of the business and its budget. A major corporation should expect to spend more money on auxiliary aids and services than a neighborhood “mom and pop” operation. A fundamental alteration in the nature of the goods and services offered would occur, for example, if an individual with a visual impairment requested management to raise the lights in a bar in which the lights are customarily turned down low to create a particular ambiance or atmosphere.

The PPA need not provide personal devices and services such as individually prescribed devices (e.g., eyeglasses) or services of a personal nature (e.g., eating, toileting, or dressing).37 However, it would probably be a reasonable auxiliary service should Carlotta request that the restaurant cut her meat in the kitchen before serving her steak if weakness in her hands prevents her from performing this task.

• Failing to furnish auxiliary aids and services when necessary to ensure effective communication, unless an undue burden or fundamental alteration would result.33 For example, Bob is deaf and needs a sign language interpreter to converse with others. When seeking counseling services at a private mental health clinic. He requests a sign language interpreter to enable him to communicate with the mental health therapist. The mental health clinic must provide the sign language interpreter unless it is an undue burden.

• Refusing to remove architectural and structural communication barriers in existing facilities when readily achievable.34 Readily achievable means removal of barriers that can easily be accomplished and carried out without much difficulty or expense.34 The ADA regulations provide 21 examples of steps that PPAs can take to remove barriers (Box 15-7).

The ADA regulations recognize that not all changes are immediately readily achievable. In concert with input from members of the disability community, the Justice Department set forth four priorities in the ADA regulations that PPAs should take to comply with the barrier removal requirements (Box 15-8).33

• Refusing to provide access to goods and services through alternative, readily achievable measures when removal of barriers is not readily achievable.36 The ADA regulations give three examples of alternatives to removal of barriers, including, for instance, providing curb service or home delivery for an inaccessible restaurant, retrieving merchandise from inaccessible shelves or racks in the grocery store, and relocating activities to accessible locations.36 For example, in pursuit of her movie hobby, Carlotta wishes to see the latest popular art film. A multiscreen cinema is showing the film, but the particular theater requires climbing a flight of steps. The theater must rotate the films to provide Carlotta access to the film that she wishes to see.36

• Failing to provide equivalent transportation services and purchase accessible vehicles in certain circumstances.38 For example, Robby Rat’s Fantasy Garden, a large amusement park, provides trams to take people to their cars in its enormous parking lots. On one of her trips Carlotta takes her grandchildren to the Fantasy Garden. The Fantasy Garden must provide accessible transportation from the parking lot to the entry gates for Carlotta.

• Failing to maintain the accessible features of facilities and equipment.29 For example, Streams Department Store must maintain its accessible ramped entrance into the store. This means shoveling snow in the winter and raking leaves in the fall so that Carlotta has access into the store on her trips to this city.

• Failing to design and construct new facilities and, when undertaking alterations, alter existing facilities in accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines issued by the Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board and incorporated in the final Department of Justice Title III regulations or the 2010 Standards, depending on the date of completion of the new or altered facilities.35,39,40,108 This is where the “building code” flavor of the ADA comes in. Specific requirements dictate how builders should design and decorate buildings to provide access. Readers can find the specifics of these 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design (2010 Standards) requirements online at http://www.ada.gov/2010ADAstandards_index.htm.

The government agencies periodically update the accessibility guidelines and related standards. For example, the 2010 Standards allow PPAs to ask individuals to remove their service animal if it is out of control and the handler is not able to get it under control or if it is not housebroken.32 The 2010 Standards also adopt a two-tiered approach to mobility devices by distinguishing wheelchairs and “other power-driven mobility devices” to include mobility devices used by individuals with disabilities but not necessarily developed for that purpose, such as a Segway PT.107 Wounded soldiers returning from war often use adapted Segway PTs for mobility. The new rules allow access for these alternative mobility devices. Another change in the 2010 Standards provides that places of lodgings must allow individuals to make reservations for accessible guest rooms during the same hours and in the same manner as people without disabilities.107

Readers should keep in mind that some state regulations differ from the 2010 Standards requirements. For example, Florida requires accessible parking spaces to have a 12-foot width (144 inches) and a 5-foot access aisle,99 whereas the 2010 Standards require a width of 8 feet (96 inches) with a 5-foot access aisle.76 The ADA regulations advise PPAs to follow the rule that provides the most access to individuals with disabilities.

The Role of the Occupational Therapist

Even though Congress passed the ADA more than 20 years ago, many examples point to a pervasive lack of compliance with access requirements.83,94 OTs are in a unique position to promote Title III’s access and inclusion mandates. With our knowledge of performance in areas of occupation, performance skills, performance patterns, activity demands in context, and client factors, we have the skills to look at how the physical environment can affect performance. We know how to make adaptations in the environment, the task, or the person to enable performance despite the limitations that an individual may have in performance skills. This knowledge base equips OTs to help PPAs comply with Title III’s access requirement as consultants by looking at limitations to accessibility and making recommendations to PPAs to improve access, physical and nonphysical (including attitudes, policies, and procedures).

OTs may find themselves working from two angles in providing access intervention. Their clients may include individuals with disabilities seeking to increase their participation in the community through increasing their access and inclusion, such as Carlotta is. Alternatively, OTs may find that their clients include proactive PPAs seeking to make their goods and services accessible to individuals with disabilities to avoid lawsuits and/or do the right thing.

In the case in which the individual with the disability serves as the client, the OT will want to perform an occupational profile that will delve into the client’s interests in the community, as was done with Carlotta. The OT works with the client to determine what the barriers are to the client’s participation in the community activities of his or her choice. In Carlotta’s case, we know that movies and going to the mall are important to her. Part of our intervention plan will include problem-solving the changes that Carlotta will need to be able to participate in these occupations, explaining her right to accommodations under Title III, and suggesting ways to advocate for the needed changes by the PPA. If the PPA fails to make changes to provide access for Carlotta, she can file an administrative complaint with the Department of Justice in Washington* or immediately file a lawsuit. The OT may serve as a witness in Title III litigation should it come to that.

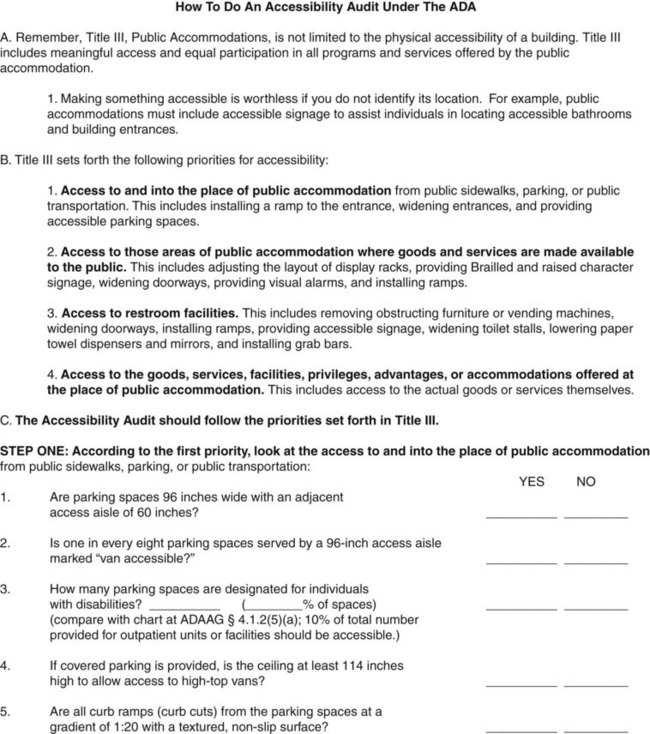

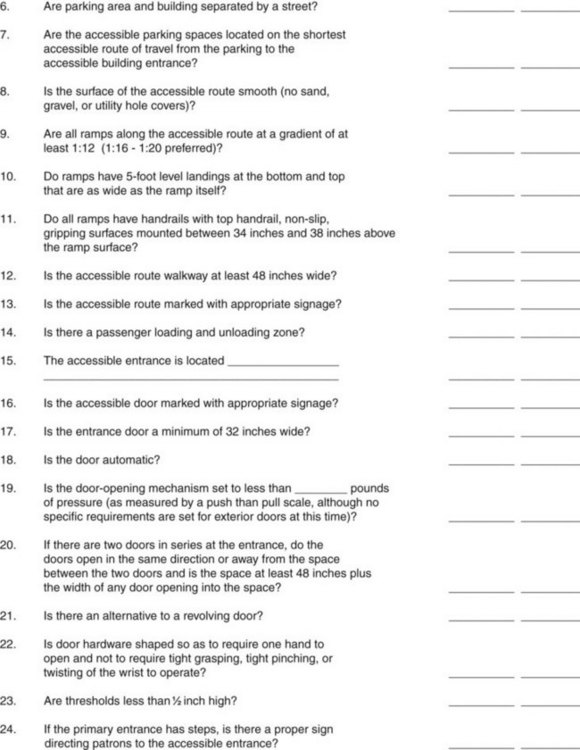

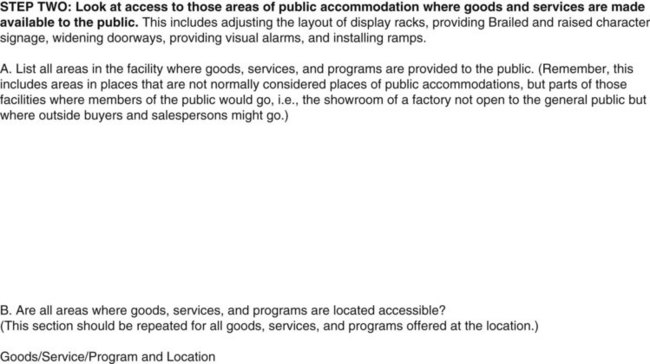

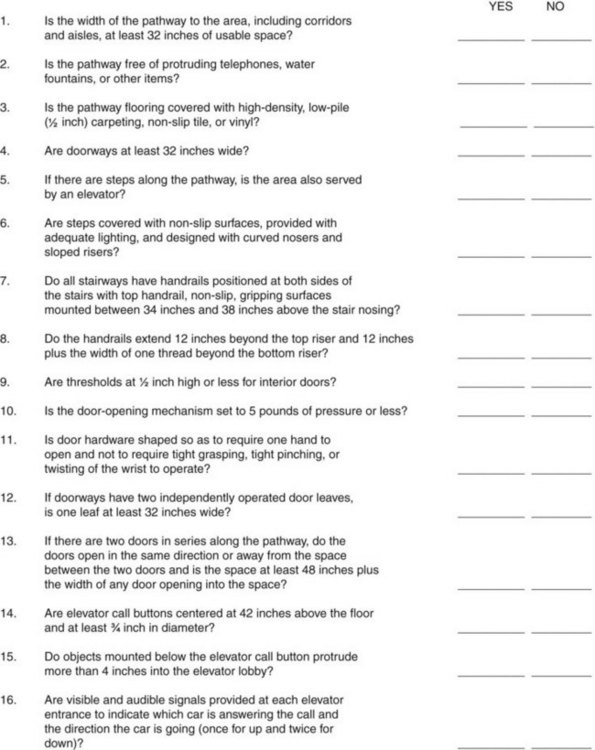

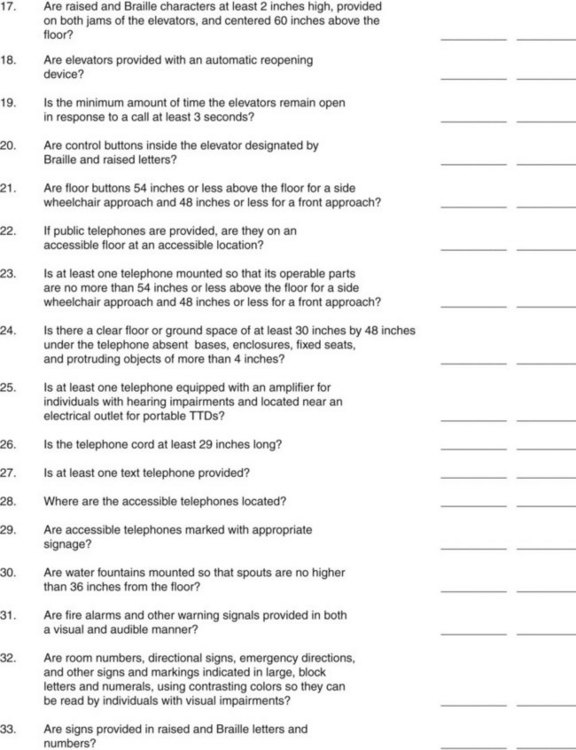

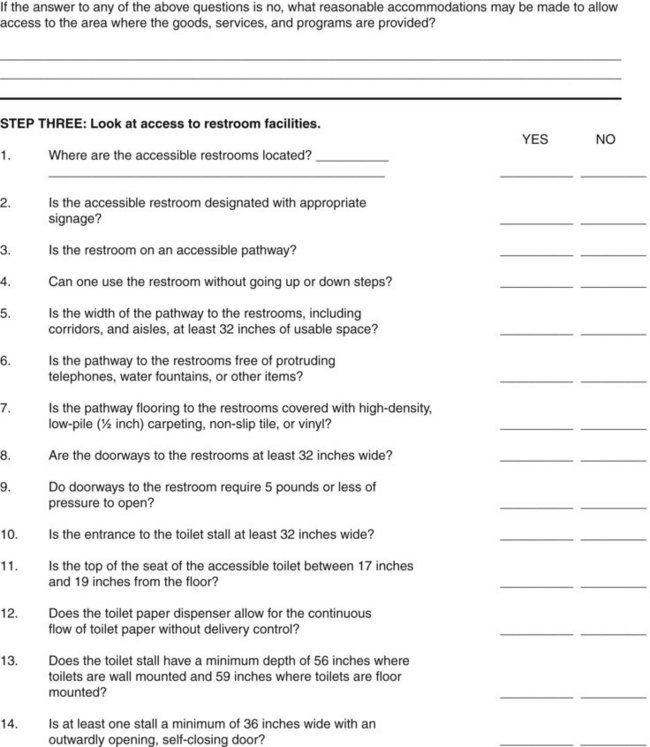

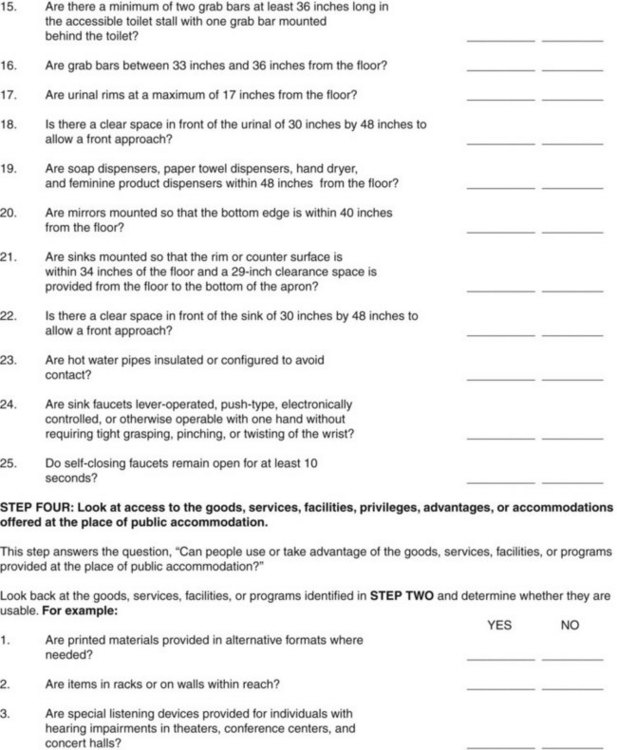

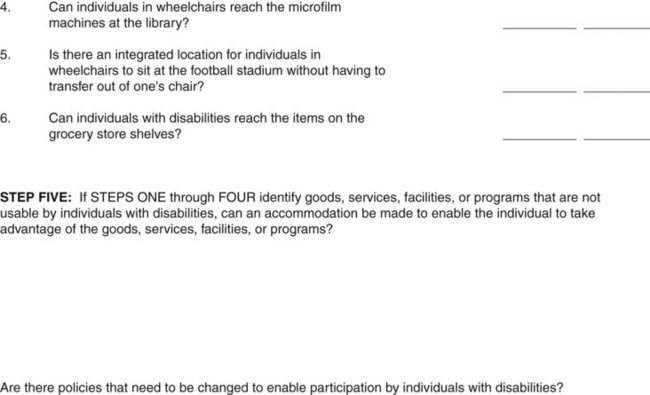

Under circumstances in which the PPA is his or her client, the OT will look at the goods and services that the PPA offers, the policies and procedures that it uses (especially customer service–related policies), and the physical access offered in the ADA-delineated priority order. Just as an employment-related ADA consultation with an employer usually begins with a job analysis, an access consultation with a PPA begins with an accessibility audit. An accessibility audit is a review of the access and inclusion practices of a PPA from a physical and policy perspective. The accessibility audit looks at the 2010 Standards requirements, the types of modifications that one can make to increase access, and readily achievable changes that one can make according to the priorities set in Title III. Figure 15-1 presents an accessibility audit that includes examining physical as well as nonphysical barriers to access according to the 2010 Standards and follows the priorities specified in Title III. OTs can also provide consultation services for employers.

FIGURE 15-1 How to do an accessibility audit under the ADA.108 (Courtesy Barbara L. Kornblau, ADA Consultants, Inc., 1992, 2002, 2011.)

Air Carrier Access Act

Carlotta’s occupational profile shows that travel is a meaningful occupation for her. To pursue that occupation now that she uses a wheelchair for mobility, she will need to know what to expect while traveling and how she can advocate for herself. The key is the Air Carrier Access Act of 1986 (ACAA). The ACAA, as amended,77 prohibits discrimination against qualified individuals with physical or mental impairments in air transportation by foreign and domestic air carriers. The ACAA applies only to air carriers that provide regularly scheduled services for hire to the public. As with the ADA and Fair Housing Act, the ACAA lists specific actions that it considers discriminatory.

Discrimination Prohibited under the ACAA

Airline carriers may not refuse to transport qualified individuals with disabilities on the basis of their disability.3 The definitions of disability are similar to the definitions found in the ADA. A qualified individual with a disability in the airline travel context means that he or she seeks to purchase or has a ticket to fly. The ACAA would protect Carlotta because she has arthritis and an airline ticket. By federal statute, carriers may exclude anyone from a flight if carrying the person would pose a direct threat to the health and safety of others.4 This parallels the direct threat criteria under the ADA. If the airline carrier excludes persons with disabilities on safety grounds, the carrier must provide a written explanation of the decision within 10 days of the refusal, including the specific basis for the refusal.6

Airline carriers may not deny transportation to a qualified individual with a disability “because the person’s disability results in appearance or involuntary behavior that may offend, annoy, or inconvenience crewmembers or other passengers.”5 Airline carriers cannot limit the number of people with disabilities that it will allow on a flight as a means of refusing transportation based on disability.2 The ACAA prohibits airlines from requiring a person with a disability to accept special services, such as preboarding, if the passenger does not request them.1 Similarly, air carriers cannot segregate passengers with disabilities even if separate or different services are available to them.8

Under the ACAA, airline carriers cannot require qualified individuals with a disability to provide advance notice of their intention to travel or of their disability as a condition of receiving transportation or of receiving services or required accommodations.7 Carlotta would not have to notify the airline in advance that she planned to fly. A limited exception to this rule exists, however. An airline carrier may require up to 48 hours’ notice for certain specific accommodations that require advance preparation. These include, for example, medical oxygen use, transportation of an electric wheelchair in a plane with fewer than 60 seats, travel with a service animal on a flight longer that 8 hours or an emotional support or psychiatric service animal, and provision of an on-board wheelchair in an aircraft that lacks an accessible lavatory.8

Airlines cannot exclude a passenger with disabilities from a particular seat or require him or her to sit in a certain seat, except to comply with FAA safety regulations such as exit row seating, which requires passengers have specific abilities to open the exit door in case of an emergency.15 Airlines must accommodate passenger seat assignments if required based on the person’s disability and requested 24 hours in advance. For example, if Carlotta traveled with a service animal that assisted her in tasks such as pulling her wheelchair and picking up items from the floor, the carrier would have to assign them to a bulkhead seat or another seat that could accommodate the service animal.14