Chapter 3 Socio-behavioural aspects of health and illness

Introduction

For a full understanding of the use of medicines and the role of pharmacy in health care it is necessary to consider sociological and psychological factors which often are tightly interwoven. These are still rather new areas within pharmacy education and research. Understanding and resolving medicine-related problems that result in suboptimal outcomes requires a scientific basis, and earlier attempts to solve these problems using ‘common sense’ approaches have been only partially successful. Therefore there is a need to broaden our perspectives by incorporating relevant social and behavioural theory and research.

The purpose of this and the next chapter is to give a broad overview of the health-related issues within a social and behavioural framework to show the importance of ‘non-biological’ factors in understanding health and illness with relevance to practising pharmacy. Illness can be seen either as a purely biophysical state or more comprehensively as a human societal state where behaviour varies with culture and other social factors. A common view is that the pure biomedical model underemphasizes the human aspects of patient care and neglects important psychosocial issues. The social sciences have a shared focus on understanding patterns and meaning of human behaviour, which distinguishes them from the physical and biological sciences.

Pharmacists have to deal with many social and behavioural issues in their daily work, either directly or indirectly. The contribution of social sciences to pharmacy and pharmacy practice can be summarized in the following three areas:

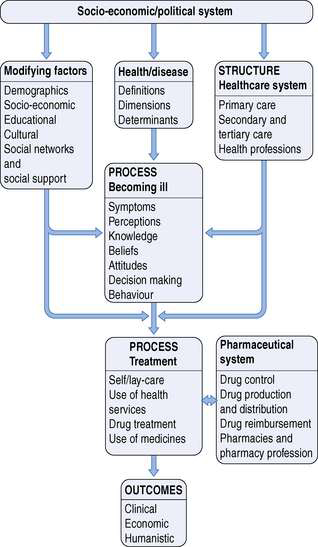

The aim here is not to be all-inclusive, but rather to highlight important contributions from social and behavioural sciences. Many of the subjects presented could fill a book on their own, so it is evident that only a brief introduction to each subject is possible in this chapter. This chapter will focus on the definitions, dimensions and determinants of health and illness. For a pharmacist it is also very important to understand the different processes involved in illness behaviour and treatment. There is also an attempt to mention the major concepts and theories in each context. An overall framework is presented in Figure 3.1. The interested reader is referred to the specialized textbooks, other books and articles on the topic that are included in the further reading (Appendix 5).

Defining health and illness

Health and illness mean different things to different people. Most young people take health for granted. We commonly think about health as the absence of signs that the body is not functioning properly or absence of symptoms of disease or injury. There is a tendency to dichotomize health; either you are healthy or not. However, health is not merely the absence of disease, but rather a continuum of different states. There are degrees of wellness and of illness. Disease, in contrast to illness, is something professionally defined and therefore also perceived to be more accurate. This has also become the essential framework for the organization we call health care. However, research shows that physicians and other experts vary greatly in their views on both physical and mental disorders and their connections. Therefore we can ask whether disease is well defined or even definable.

Illness is more a state defined by a layman or a reaction to a perceived biological alteration of the body or mind. It has both physical and social connotations. Illness is also highly individual. It is influenced by cultural, social and other factors. It is important to note that a person may have a disease and not be ill, might be ill but not have a disease or might have both an illness and a disease. Sickness is also a socially defined condition, a social status conferred on an individual by other members of the society. This will be further elaborated in the context of the sick role (p. 30).

The most widely used definition of health or wellness is that of the World Health Organization (WHO), which states that: ‘Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of diseases and infirmity’. This definition has been widely quoted, but is less used in daily practice in health care. The definition has to be seen more as a goal that is actively sought through positive actions and not merely as a passive way of avoiding disease-causing agents. Different definitions and models of health also have practical relevance, as they are needed to guide policymakers in their allocation of resources.

Dimensions of health

The WHO definition distinguishes physical, mental and social health. In some narrower definitions, only physical and mental health are included, thus implicitly excluding resource allocation for other areas. A broader definition may emphasize social and other dimensions as well. One of the dangers is that the broader the definition, the more we tend to medicalize our society as we include more and more everyday things as part of the responsibility of clinical medicine and public health (e.g. loneliness, attention deficit disorders, domestic violence). On the other hand, these broad definitions allow us to examine health issues more comprehensively. The definition used will also have economical and other consequences.

Most of us see physical health as being free from pain, physical disability, acute and chronic diseases and bodily discomfort, i.e. as the normal functioning of the body’s cells, organs and systems. However, our prior experiences of disease, age, education and a variety of other personal and social factors will influence our perception of physical health.

Mental health is composed of the ability to deal constructively with reality and adapt to change without feeling threatened by it. A positive self-image and an ability to cope with stressors and develop intimate relationships are also part of mental health. Furthermore, enjoying the pleasures of ordinary life and making plans for the future are important aspects of mental health.

The role of spiritual health has raised less research interest. Some might consider this as merely part of the mental health dimension, while others argue that it is a separate dimension. It should not be confused with religion or religiousness. A sense of spiritual well-being is possible without belonging to an organized religion. Spiritual health has been characterized by Miller & Price (1998) as the ability to articulate and act on one’s own basic purpose of life, giving and receiving love, trust, joy and peace, having a set of principles to live by, having a sense of selflessness, honour, integrity and sacrifice and being willing to help others achieve their full potential. By contrast, a negative spiritual health can be described by loss of meaning in one’s life, self-centredness, lack of self-responsibility and a hopeless attitude.

The impact of social health on the well-being of the individual has been widely demonstrated. Social integration, social networks and social support have both direct and indirect influences on health. A low socio-economic status defined by educational level, income and occupation is closely related to higher morbidity and mortality.

Determinants and models of health

The history of medicine contains several theories, or frameworks, for the origins of disease. One of the earliest explanations was that mystical forces like evil spirits could cause physical and mental illness. The father of medicine, Hippocrates (460–370 BC), developed the humoral theory to explain why people get sick. According to this theory the body contains four fluids (blood, phlegm, yellow and black bile) called humours. When these are in balance we are in a state of health and, accordingly, when there is an imbalance we are sick.

In the Middle Ages illness was closely related to religious beliefs and sickness was often interpreted as God’s punishment for doing evil things. Priests led most of the practice of medicine and became more involved in treating the ill, sometimes torturing the body to drive out evil spirits. After the Renaissance different scholars became more human-centred, one of the most influential in the 17th century being René Descartes. Descartes’ impact on scientific thought has been extensive and lasted for centuries. His main health-related ideas can be summarized in three points: first he saw the body as a machine and described how action and sensation occur, second he proposed that body and mind, although separate, could communicate, and third that the soul in humans leaves the body at death.

In the following centuries scientists learned more and more how the body functions with the help of the microscope and other technical advances. New theories, like the germ theory, tried to explain disease by microbes, etc. All these advances led to the foundation of the current biomedical disease model, which proposes that all diseases or physical disorders can be explained by disturbances in physiological processes which result from injury, biochemical imbalances and bacterial or viral infections. The biomedical model assumes that disease is an affliction of the body and is separate from the psychological and social processes of the mind.

A more recent and comprehensive model is the biopsychosocial model that involves the interplay of biological, psychological and social aspects of a person’s life.

Additionally, some ancient beliefs about ill health and disease, still prevalent among primitive tribes and in certain cultures, continue surprisingly strongly in industrialized countries alongside conventional medicine. Wrong behaviour, diet, dirty water, weather, accidents, black magic or witchcraft, spirits and God are all mentioned as causes of diseases. ‘Don’t wet your feet or you’ll catch a cold’ typifies certain superstitious thinking.

Genetic and biological determinants

In current medicine there is much interest in the genetic basis of disease. The origin of most health problems seems to lie in human genes. The newspapers have declared the finding of the alcoholism, antisocial behaviour and obesity genes among others. This leads to the lay impression that once the genetic code has been solved all health problems will also be solved without any need to pay attention to, for example, health habits. This is, of course, far too simplistic a way of thinking. The scientific interest in this field lies in interactions between genetic endowment and psychosocial factors in early childhood. Laboratory research with animals has shown that genetically predisposed spontaneously hypertensive rat pups cross-fostered by normotensive mothers did not develop hypertension as they matured. This study shows that poor genetic endowment can be overruled by favourable upbringing and environment.

Behavioural determinants

The leading causes of death today – heart disease, cancer, stroke and accidents – are all associated with behavioural risk factors. The origin of many chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension can be found in lifestyle factors. Sedentary lifestyle explains a lot of the causes of these diseases without the need to go to the gene level. Sometimes positive genetic endowment can explain why poor health habits are not leading to poor health. It is also remarkable that the remedy for most of these lifestyle diseases can be found in simple behavioural remedies like increased physical activity, reduced stress, balanced diet and quitting smoking.

Behaviour and mental processes are the focus of psychology and they involve cognition, emotion and motivation. Cognition involves perceiving, knowing, learning, remembering, thinking, interpreting, believing and problem solving. Emotion is a subjective feeling that affects and is affected by our thoughts, behaviour and physiology. Emotions can be positive/pleasant or negative/unpleasant. People whose emotions are more positive are less disease prone and more likely to recover quickly from an illness than those with more negative emotions. Motivation applies to explanations of why people behave the way they do, e.g. why they start a health-related activity or why they do not take their medicines as prescribed. Psychology is also interested in interpersonal relationships, which includes thinking, feeling and doing with someone else. Descriptions of cognition, affect, behaviour and interpersonal interactions overlap and it may be difficult to separate them; for example, in a situation causing anxiety the person may think he is not in control of the situation (cognitive component), he is afraid (affective) and his hands are sweating (behavioural) and he may ask somebody to help support him (interpersonal).

Stress is a condition that results when personal/environmental transactions lead the individual to perceive a discrepancy (real or not) between the demands of a situation and the resources of the person’s biological, psychological or social system. The connection between body and mind is also reflected in how people react to stress. It can produce changes in the body’s physiology and cause illness. Stress can release hormones, especially catecholamines and corticosteroids, by the endocrine system through arousal. Effects on the cardiovascular system can be important and stress-related emotions such as anxiety and depression can play a critical role in the balance of the immune system. Stress can be described as a stimulus. Events and circumstances that are perceived as threatening or harmful, and which produce feelings of tension, are called stressors. However, stress can also be seen as a response to stressors. The person’s physiological and psychological response to a stressor is called strain. Stress can be seen as a process including stressors and strain and the relationship between the person and the environment as continuous interactions and adjustments.

Stress can also affect health through the person’s behaviour. People who experience high levels of stress tend to behave in a way that increases their chances of becoming ill or injured. They consume more alcohol and drugs and smoke more than people who experience less stress. Accident rates are also higher among those with elevated stress.

Environmental determinants

The role of environmental factors (biological, chemical, physical, mechanical) in influencing human health is widely accepted. The main pathways into the human body are air (outdoor and indoor), water, food and soil. The role of these environmental factors in the pathogenesis of asthma, hay fever and others is clear. However, environmental factors have a much broader impact, starting in the prenatal phase (e.g. the use of drugs like thalidomide during pregnancy has led to severe birth defects).

The importance of the environment has been demonstrated in migrant and time-trend studies of disease. When people change environment their disease risk patterns change. One interesting demonstration is the case of Japanese migrants. The further they went across the Pacific the higher their incidence of coronary heart disease and the lower their rate of stroke. Japanese in Hawaii have rates of heart disease intermediate between those in Japan and those in California. Environment and lifestyle are the most probable explanations of these differences.

There is also a distinction between individual risk factors and environmental causes of disease. Differences in individual risk factors explain only a part of the variation in the occurrence of disease. While reducing high risk factors might be beneficial for the individual concerned, it makes a limited contribution to reducing disease rates in the whole population. Rose has suggested that the causes of individual differences in disease may be different from the causes of differences between populations. A risk factor does not necessarily cause the disease even if it is associated with it.

Socio-economic determinants

These factors are also ‘environmental’, but it can be debated as to whether they are genuine factors determining health or whether they only represent predisposing factors. Society establishes certain health values, which are often reflected in the media. These values can be both positive and negative. Being fit and healthy is ‘good’ and exemplifies a positive value, while celebrities smoking cigarettes or marijuana exemplify a negative value. The family is the closest and most continuous social relationship for most people. Therefore, many health-related habits, behaviours and attitudes are learned and modelled from this context. The degree of support or encouragement received from family members and friends for partaking in a health-related activity might be an important factor. This is dealt with in more detail later (p. 38).

In developing countries factors such as poverty, poor nutrition and poor resistance to pathogens are all interrelated with a poor health status of the population. Similarly, historical statistics from industrialized countries show that over the last two or three centuries there has been a strong positive correlation between improved health, life expectancy and improved economy. In most countries the relationship between socio-economic status and disease runs across the social hierarchy. This shows that the relationship between socio-economic status and health is a question of relative deprivation rather than absolute deprivation. This linear association can only be partially explained by lifestyle factors. Usually people with a higher socio-economic status have healthier habits than those from lower socio-economic groups. Similarly there are huge differences in life expectancy between western and eastern European countries that can be attributed to socio-economic factors.

Interaction of different factors

It is evident that no single factor can alone explain the health of a nation, demographic group or individual. It is difficult to capture all the relevant features and their relationships. Having good genes can prevent some people from getting a disease; on the other hand, somebody with poor genes can get ill regardless of a healthy lifestyle and other positive factors. Considering the impact of all aspects of a person’s life as a total entity in understanding health and illness is called holism.

One comprehensive attempt to describe/model the interactions between different factors is the ‘nested model of health’. This model consists of two levels of activity, the individual and the community level. The individual level is composed of five different categories:

These environments are thought to affect each other and to affect and be affected by the individual. The individual level is nested/located in the centre of the community level. This community level, which is the main focus of health policy decision makers, is composed of four components, the political/economic climate (e.g. unemployment level), the macro physical environment (e.g. air quality), social justice/equity (e.g. social security system) and local control/cohesiveness (e.g. local planning efforts). These four components are interrelated and changes in them are expected to lead to changes in the health of individuals.

Process of illness

Becoming ill

Understanding illness behaviour can help pharmacists appreciate and accept why patients respond differently to seemingly similar pain or discomfort. The general criteria by which people view themselves as ‘well’ include a feeling of well-being, an absence of symptoms and an ability to perform normal functions. This is the baseline situation against which any changes are judged. When studying health-related behaviour it is important to consider how behaviour changes with the health status of the individual. Kasl & Cobb defined three types of behaviour that characterize three stages in the progress of disease:

Ways of identifying and reacting to symptoms

Symptoms can be classified into three broad groups: those symptoms noted by the patient, symptoms noted by behavioural changes and patient complaints. A behaviour which in some situations is regarded as normal can in other situations be regarded as a sign of illness. Not all symptoms can be regarded as medical, as they may have a natural explanation, like tiredness. Different symptoms may be perceived very differently, depending on the person, setting and situation. Differences in illness behaviour occur as a function of the immediate experience, past experiences and the patient’s information processing, organizing and recall. The significance of symptoms is judged according to the degree of interference with normal activities, the clarity of symptoms, the person’s tolerance threshold, familiarity of symptoms, assumptions about cause and prognoses, interpersonal influence from the lay-referral system and other life crises making the symptoms appear more severe. The subjective and psychosocial aspects of an incident can be more important in determining decision and action than the symptoms themselves.

The experience of illness involves affective and cognitive reactions to illness, in which the patient undergoes emotional changes and attempts to understand the illness. Bernstein & Bernstein have described these emotional reactions to illness and treatment in the following ways:

Women are more likely than men to interpret discomfort as a medical symptom; they also recall and report more symptoms. These differences may partly be explained by a higher interest in and concern with health issues among women than men. The family often plays an active role in the symptom identification process. Other family members may recognize some symptoms before the person does. The family also takes part in the interpretation process of symptoms. The culture is also an important factor influencing the process of symptom identification and evaluation. Some cultures describe more readily common symptoms as medical, while others tend to suppress signs of medical symptoms. There might also be differences between generations in this respect. What was earlier considered as normal may today be seen as something requiring medical attention. The individual’s feeling of anxiety may also explain the symptom levels, since high anxiety has been associated with the identification of many symptoms.

Sick-role behaviour

When people perceive themselves to be sick they adopt the so-called ‘sick-role behaviour’. According to Parsons this includes the following components:

It has been found that not all people follow these patterns of the sick role and it should be seen more as a general framework for understanding illness behaviour. However, this framework is not able to explain variations within illness behaviour; it is not applicable to chronic disease and often not to mental illness. There are also certain diseases where there might be some unwillingness to grant the exemptions from blame. These include certain conditions related to smoking, overuse of alcohol and AIDS. But even epilepsy has been stigmatized in many cultures.

The role of personality in illness

Personality has been shown to be associated with illness. People who have high levels of anxiety, depression and anger/hostility traits seem to be more disease prone than others. These emotions are part of reactions to different types of stress. People handle stressful situations in different ways. People who approach stressful situations more positively and hopefully are less disease prone and also tend to recover more quickly if they get ill. People who are ill need to overcome their negative thoughts and feelings in order to recover more quickly.

The cardiologists Friedman and Rosenman were the first ones to describe differences in behavioural and emotional style, when studying the behaviour of heart patients. These patterns have been named Type A and Type B behaviour. The Type A behaviour pattern is characterized by:

The Type A pattern may also increase the person’s probability of getting into stressful situations. The relationships between Type A behaviour and psychosocial factors are very complex, involving multiple levels of human experience.

Type B behaviour is opposite to Type A, with individuals taking life more easily with little competitiveness, time urgency and hostility. Interestingly the overall evidence for an association between Type A and B behaviour and general illnesses is weak and inconsistent. However, many studies, but not all, have shown a clear association between Type A behaviour and coronary heart disease.

Health knowledge, beliefs and attitudes

There are different definitions of what this knowledge is. Sometimes it may include a variety of things such as beliefs, expectations, norms and cognitive perceptions. If this is the case, knowledge has to be considered in a wider framework than merely having some factual knowledge about diseases and treatment. One of the goals in current health care is to improve the patient’s problem solving capacity. The starting point is providing the necessary information and improving the factual knowledge of the patient. It has been shown several times that knowledge alone is not sufficient to ensure change in behaviour, which is often the goal. Preventive behaviours, the treatment process and taking medications all require a certain amount of knowledge. The current trend emphasizing guided self-care in chronic diseases such as asthma, diabetes and hypertension requires a well-informed patient. The aim is to produce patients who actively participate in their own treatment. In research settings, the narrow approach towards knowledge usually involves using a knowledge index (set of questions) that the patient has to answer before and after an educational intervention.

Attitudes have been defined as states of readiness or predisposition, feeling for or against something, which predisposes to particular responses. They involve emotions (feelings) and knowledge (or beliefs) about the object and emanate in behaviour. Attitudes are not inherited but learned and, though relatively stable, are modifiable by education.

The health belief model

The health belief model, which was originally developed by Rosenstock and his colleagues to predict the use of preventive health services, has been extensively used during the last two decades to try to explain various health behaviours. The model was further developed for predicting health behaviour in chronic diseases and reformulated for predicting compliance with healthcare regimens.

The elements of the model are subjective perceptions which can be modified, at least in theory. According to the model, the probability that a person will take a preventive health action – that is, perform some health, illness or sick-role behaviour – is a function of:

According to the model, the more vulnerable the person feels and the more serious the disease the more likely it is the person will act. Furthermore, various factors that result from the perceptions are expected to modify this motivating force. These factors include demographic, socio-economic and therapy-related factors as well as the illness itself and the prescribed regimen. Prior contact with the disease or knowledge about the disease may modify the behaviour. Some incidents, so-called ‘cues to action’, are also expected to trigger the behaviour. These include, for example, a mass media campaign, magazine article, advice from significant others or illness of a family member or friend.

The concept of perception is important in the health belief model. It is the patient’s and not the pharmacist’s perceptions that drive the decisions and behaviours of the patient. In studies of compliance with prescribed medications the concept of personal susceptibility has been modified because the illness has already been diagnosed. One approach includes examining the individual’s estimate of or belief in the accuracy of the diagnosis. This concept has also been extended to estimating resusceptibility or measuring the individual’s subjective feelings of vulnerability to various other diseases or to illness in general. Studies show that in hypertension, for example, the threat posed by hypertension and the perceived effectiveness of treatment in reducing this threat seem to be important predictors of compliance. Likewise the perceived control over one’s own health is important. There is some controversy about the chronology of these beliefs and whether they precede or develop simultaneously with health behaviour.

The health belief model and common sense might tell us that the patient’s decision to seek health care, accept a diagnosis and engage in health-related behaviours would be related to the seriousness of the disease. Research indicates this may not always be the case. Patients’ health behaviours are a function of many psychosocial variables. Reasons why humans may behave illogically are dealt with in more detail in the section ‘The conflict theory’, below, and also in the section ‘Decision analysis and behavioural decision theory’ (p. 34).

The theory of reasoned action

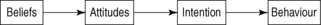

According to the theory of reasoned action by Ajzen & Fishbein, a person’s intention is the best predictor of what he will do. The person’s intention is determined by his attitude regarding the behaviour and whether he thinks it is a good or bad thing to do. This assessment is based on behavioural beliefs about possible outcomes of the behaviour and evaluations of whether these outcomes would be rewarding. The other attitude represents the impact of social pressure or influence. These are based on normative beliefs regarding others’ opinions about the behaviour and the person’s motivation to follow those opinions, i.e. what do other people think I should do? The theory proposes that the subjective norm and the attitude regarding the behaviour combine to produce an intention, which leads to the behaviour.

If behaviour is determined by beliefs, this raises the question of what factors determine beliefs? These factors would include things like age, sex, education, social class, culture and personality traits. These variables influence behaviour indirectly rather than directly. One of the problems with the theory is that people do not always do what they plan, i.e. intentions and behaviour are only moderately related. Another problem is that people do not always act rationally. Irrational decisions such as delaying medical treatment when symptoms exist cannot be explained by the model. Neither does the model include prior experiences with the behaviour, which might be an important factor to consider, since past behaviour is a strong predictor of future practice of that behaviour.

The conflict theory

The conflict theory has been used to explain rational and irrational decision making. According to the model the process a person is using in arriving at a health-related decision involves five stages. It starts when something challenges the person’s current course of action. It can be a threat (e.g. symptom) or a mass media alert about, for example, the danger of narcotics or an opportunity (e.g. free membership to a health club). The different stages of the conflict theory model are:

The decision process can be aborted at any point. Errors in decision making are often caused by stress, information overload, group pressure and other factors. The way people cope with stress has an important role in health, illness and sick-role behaviour. According to the conflict theory, a person’s coping with a conflict is dependent on the presence and absence of risks, hope and adequate time. Different combinations of these may result in different types of behavioural response. For example, when there are perceptions of high risk in changing the behaviour and no hope in finding a better alternative, a high level of stress is experienced. Denial and shifting responsibility to someone else are typical responses, with delays in seeking care when needed. The perception of serious risk, and belief in a better alternative, but also a perception of running out of time, also create high levels of stress. People search desperately for solutions and may choose an alternative hastily if promised immediate relief. Different untested cancer quacks are good examples where unscrupulous people try to make use of this kind of situation. The perception of serious risk, with a belief that a better alternative will become available and there is time to search for it, results in low levels of stress and rational choices.

Locus of control

It has been claimed that how individuals perceive their ability to influence disease and the treatment is an important determinant of health behaviour. People have been categorized into two groups: those with an internal locus of control and those with an external locus of control. The former tend to perceive that they are in control of their own health by their actions and behaviour, while the latter consider that health is externally determined and their actions have little or no effect. Therefore those with a strongly internal locus of control should tend to practise behaviours that prevent illness and promote health. Research has shown that this is the case, but the relationship is not very strong. This shows that the locus of control is just one factor among many others that determine health behaviour. Belief in internal control is likely to have a greater impact among people who place a higher value on their health than among those who do not.

Self-efficacy and social learning

Sometimes performing a health action is hard to do because it is technically difficult or it may involve several steps. Therefore the belief in the success in doing something – called self-efficacy – may be an important determinant in choosing or not choosing to change behaviour. People develop a sense of efficacy through their successes and failures, observations of others’ experiences and assessments of their abilities by others. People assess their efficacy based on the effort that is required, complexity of the task and situational factors, e.g. the possibility of receiving help if needed. People who think they are not able to quit smoking will not even try, while people who believe they can succeed will try and eventually some may even succeed.

Those with a strong sense of self-efficacy show less psychological strain in response to stressors than those with a weak sense of efficacy. People differ in the degree to which they believe they have control over the things that happen in their lives. Those who experience prolonged, high levels of stress and lack a sense of personal control tend to feel helpless. Having a strong sense of control seems to benefit health and adjustment to sickness.

As environmental factors and expectations directed towards the individuals change, they must either intensify their activities or change their environment. Individuals have different capabilities of coping and different coping strategies. According to the social learning theory, people change their environment with the help of symbols they choose in accordance with their values, norms and goals. On the other hand, the environment changes the individual’s behaviour by rewarding beneficial activities and punishing or not rewarding activities that harm the environment. Through the socialization process the individual adopts the values and norms of the community, is socialized as its member and gains identity. Through this process the individual has learned to act efficiently in social systems.

Antonowsky has used the ‘sense of coherence’ concept, which is an extensive and constant feeling of an individual’s internal and external environment being in harmony with each other. Every individual has characteristic psychosocial potentials that include material resources, intelligence, knowledge, coping strategies, social support, arts, religion, philosophy and health behaviour. Antonowsky calls a sense of coherence ‘salutogenic’ or health generating. Disease–health is a continuum, at one end of which is a high degree of coherence and health (ease) and at the other end a low degree of coherence and illness (dis-ease). External factors that the individual considers threatening mobilize the defence mechanisms and cause stress conditions in the individual. Prolonged stress is disease generating and causes the condition dis-ease.

Coping

Because of the emotional and physical strain that accompanies it, stress is uncomfortable and people are motivated to do things that reduce their stress. The concept of coping is used to describe how people adjust to stressful situations in their life. Coping is the process by which people try to manage the perceived discrepancy between the demands and resources they appraise in stressful situations. Coping means the ability to meet the demands of new situations and solve the problems with which one is confronted. Coping is determined by situational and personal determinants. At the individual level, external factors turn into stress factors if previous experiences together with personality traits, consciously or unconsciously, are considered as threatening or diminish self-esteem. Coping efforts can be quite varied and do not necessarily lead to a solution of the problem. It can help the person to alter his perception of a discrepancy, tolerate or accept the harm or threat and escape or avoid the situation. The coping process is not a single event.

Coping mechanisms

Coping can alter the problem or it can regulate the emotional response causing the stress reaction to the problem. Behavioural approaches include using alcohol or drugs, seeking social support from friends or simply watching TV. Cognitive approaches involve how people think about the stressful situation, e.g. changing the meaning of the situation. Emotion-focused approaches are used when people think they cannot do anything to change the stressful situation. Problem-focused coping is used to reduce the demands of the stressful situation or to expand the capacity and resources to deal with it. The two types of coping can also be used together. Sarafino (2005) has summarized commonly used methods of coping as follows:

Decision analysis and behavioural decision theory

Decision analysis is a systematic way of studying the process of decision making among patients, pharmacists and physicians. This is a widely used tool in pharmacoeconomics today (see Ch. 19). It usually involves assigning numbers to perceived values of the therapeutic outcomes and the probability that the outcome will occur. This gives a utility of each outcome and the one with the highest utility would be chosen. One problem is that humans do not always make decisions logically or treat information as value free.

Why don’t humans behave logically? One explanation that has been offered is that humans are biased when making decisions under uncertainty because we fail to appreciate randomness. We believe that there are known causes and effects for all phenomena and we have a need to be able to explain outcomes. It is easier to explain, even incorrectly, than to have to deal with uncertain situations. People also tend to be inconsistent in judgment, often because of difficulties in remembering how a judgment was made. Another reason is that we seldom receive feedback from negative decisions, for example if we decide not to take the medicine we do not know how effective it would have been.

Behaviour decision theory has been used to understand how patients make decisions about their medicine and health-related behaviour. These include acquisition of information, information processing, making decisions under uncertainty and interpreting outcomes of that decision. It has been found that patients are more likely to take a health risk to avoid an aversive situation than to gain a positive health outcome. Patients are also more likely to choose a certain outcome than an outcome with a high probability of occurrence, even if the certain outcome is less valued than that one with a high probability of occurrence. When a person has already invested time and money on a product or activity they are likely to continue it, even if it does not appear to be effective.

Hogarth has described different biases that people tend to have in decision making which may be helpful in understanding patient choices about health behaviour. We tend to believe more in well-publicized events than in those that are less publicized. This has direct links with the consumer’s choice of well-advertised over the counter (OTC) medicines. There is a tendency to believe what matches our existing beliefs. This selective perception has direct implications for health education in pharmacies. We also tend to believe real incidents more than abstract statistics. Positive experiences from a family member quitting smoking is more likely to be effective than showing statistics about future (uncertain) consequences of smoking. Two incidents occurring close in time and place tend to be regarded as causal. Becoming ill after having taken a medicine (regardless of cause and effect) would usually trigger a response of aversion next time seeing the same medicine. We are reluctant to change our beliefs, even when given new data, and tend to discount the new information rather than discount our belief. Very few instances of an occurrence are needed for us to form a new belief if it has a strong effect upon us. This has direct implications to the experience of side-effects of drugs. We also believe something is more likely to happen if we want it to happen. A decision that was successful is more likely to be considered to be due to the knowledge and wisdom of the decision maker. On the other hand, a decision resulting in bad outcomes is likely to be blamed on others.

Theory into practice – the process of behaviour change

A lot of pharmacists’ activities will focus on changing the behaviour of patients. Without going into the ethical aspects of behaviour change, we will concentrate on the process of change. It has been proved several times that merely using common sense is not enough to reach permanent behaviour change. Using a common-sense approach would assume that, given the facts, people will be able to change their behaviour in a direction anticipated by the healthcare professional. A simple example illustrates the limits of this approach – why do so many people still smoke cigarettes despite knowing all the negative consequences of smoking?

Even if many of the behavioural theories are far from complete or comprehensive, they may guide us in improving the outcome of behavioural interventions. Behaviour change includes a long list of steps that need to be taken before it is finalized:

The treatment process

Self- and lay care

During the 1970s and 1980s a new trend emphasizing the role of the individual and patient emerged as a part of a more general trend called consumerism. People have become more committed to getting and taking control of their own lives and assessing the impact of their behaviour on their health. Different self-care and self-help movements were a direct result of this trend. The same trend has been obvious in most countries although the starting time and speed of it has varied. At the same time the dominant role of healthcare personnel has diminished. With new information sources, and especially the Internet, the trend continues to grow and spread to countries where physicians and other healthcare personnel still dominate. This new trend has included a much more critical attitude towards what is being done in health care and the quality of care given. Patients are asking more questions, seeking more information and taking a more active role in their health care. They have a better basic education and greater knowledge, especially about their own disease and treatment of that disease.

The new trend has also put increasing demands on pharmacists regarding their knowledge base, especially in therapeutics but also in communication. The priorities in treatment goals may differ between the patient and the treating physician and this calls for negotiation. One aspect is that patients’ views have to be taken seriously.

According to the self-care philosophy, people should be given more responsibility for their own health. One way this can be achieved is to emphasize the role of self-care in treating minor ailments using home remedies and an increased number of self-medication products. Especially in the 1980s and early 1990s this trend was obvious in many countries. The most common ‘action’ in response to a perceived health problem has been to ignore the problem or wait for a few days. It is estimated that some 30–40% of health problems are dealt with in this way. Of those who take some action, 75–80% self-diagnose and use self-treatment, while only 20–25% seek professional care. Therefore a seemingly small change in this ratio (towards using more professional care) has a substantial impact and burden on the official healthcare system. Of those who use self-treatment, some 70–90% are self-medicating, and of those self-medicating, some 80% are using OTC drugs. Home remedies such as onion, garlic and warm drinks, as well as different herbal products, vitamins and minerals, are widely used all over the world. Some of the newly emerging preparations are marketed with high promises of eternal youth and health, the evidence base for which is nonexistent or weak.

Before people decide to seek medical care for their symptoms they get and seek advice from friends, relatives and co-workers. These advisors form a lay referral network that provides its own information and interpretation regarding the symptoms, recommending home remedies, self-medication, professional help or consulting another ‘lay expert’ who may have had a similar problem.

The pharmacy is often the first place where people come to seek help within the healthcare system. Increased self-care includes also potential risks in that lay people may not be able to distinguish between serious and non-serious symptoms. Certain situations may demand professional care without further delay caused by inappropriate self-medication practices. The lay referral network can in some cases be guilty of causing delay in seeking care. This treatment delay has been divided into three stages: appraisal delay, illness delay and utilization delay. Appraisal delay is the time it takes to interpret a symptom as a part of an illness. Illness delay is the time between recognizing the illness and the decision to seek care. Finally, utilization delay is the time between the decision to seek care and actually using a health service.

There has also been concern about misuse of OTC drugs such as laxatives, codeine-containing cough medicines, etc. The other side of the coin is saved resources in health care when there is less reliance on professionals. This seems to be an important aspect as healthcare budgets tend to increase more rapidly than the general inflation rate.

Primary care

Simultaneously with emerging self-care, the concept of primary health care was introduced. In 1977 the World Health Assembly of the World Health Organization adopted the concept of Health for All by the Year 2000. The following year this concept was translated into the so-called Alma Ata Declaration at the Alma Ata conference on primary health care. The focus was on making health care more accessible and lowering the healthcare costs and thus improving the quality of life for the whole population. According to the declaration, primary health care should include:

Primary health care focuses on principal health problems and must be part of national health policy and planning. The conference recommended a re-evaluation of health priorities, putting less emphasis on curative facilities, especially in third world countries. The conference also called for cooperation and commitment in striving for an acceptable level of health for all people by the year 2000.

The scope of public health is population based rather than individually based. Public health problems are not a series of individuals presenting diseases to a healthcare provider for cure, alleviation or prevention, but are considered in the context of the community. It is a public health problem to determine the prevalence of a disease in the community, compare that with figures from previous years and plan health services to reduce the prevalence. Public health includes enumeration, analysing and planning, but also specific actions to be taken. Public health exists on two levels: the micro level, for example performing some public health function such as immunization or preventing inappropriate use of illicit drugs, and the macro level, with activities like planning or policy formulation.

Factors influencing the use of health services

The structures of the healthcare systems in different countries have a lot of similarities but also a lot of differences. The system is the sum of historical development, culture and economic factors. In some countries there are actually several different systems in place within the healthcare system. It is not within the scope of this chapter to describe these different systems, rather to highlight some of the current issues in organizing the health care of the citizens and to highlight some socio-behavioural factors influencing the provision of care. It may seem obvious that when having bad angina you will need hospital care and you will be provided with all the technical know-how and help in dealing with the problem. However, the country you happen to live in, the insurance policy you have, the services available, quality of care, etc. will all influence the outcome of the disease. The organization and financing of health care, the environment of medical care, social and cultural factors all influence the care that you will receive.

Demographic factors

Several important differences have been reported between different age groups and between genders. However, few reports have been able to validate the reasons for these differences. As mentioned before, it is well known that women report more symptoms and that they have a lower threshold of pain and discomfort and are more likely to seek care. Men are more hesitant than women to admit to having symptoms and to seek medical care for these symptoms. This can be a result of perceived sex-role stereotypes – men should be tough and independent and ignore or endure pain. Women use physician services more than men in all age groups except for the first few years of life. Regardless of this, men have a higher mortality and shorter life expectancy at all ages.

In general, young children and the elderly use physician services more often than adolescents and young adults. Age differences in health behaviour cannot be explained by biological ageing alone. Elderly people have different views on health and illness, symptoms, healthcare use and drugs. There is a danger in labelling all elderly people as having similar attitudes concerning health issues, but, as with younger persons, among the elderly there are also a wide variety of views on health and treatment. Certain ideas are more prevalent among the elderly than the young. The differences can partly be explained by so-called cohort effects, meaning people of the same age have been exposed to the same kind of experiences and attitudes in society and therefore are also likely to share certain behavioural characteristics.

Cultural and socio-economic factors

Ethnic and cultural background may explain some differences in symptom experience, how people seek medical care and how they take their medicines. In the 1950s a classic study about how people deal with pain found big differences between Italian, Jewish, Irish and Yankee (Old American) hospitalized patients. Italian and Jewish patients were more likely to respond emotionally and expressively to pain than Irish or Yankee patients, who tended to deny pain. Italian and Jewish patients showed their pain by crying, complaining and demanding, while the Irish and Yankee patients preferred to hide their pain and withdraw from others. More recent studies among immigrants in the USA found that the differences in willingness to tolerate pain diminish in succeeding generations. Other similar studies have shown cultural differences among European countries and the USA, e.g. in perception of fever and the need to medicate children’s fever.

There are also differences in seeking care according to social class, education and income. These factors all point in the same direction – those who are better off also use more health services. Different models of why people seek or do not seek health services have been proposed. The health belief model has also been used in this context.

Social support

Social environments and networks are important in the growth, development and health of people. Social support is an important factor in all phases of the process of illness and the treatment process. Social support relates directly to the general and universal needs of people. The best known theory is that by Maslow. According to his theory, human needs are hierarchical, starting with basic physiological needs, followed by safety needs, belongingness and love needs, esteem needs, and finishing with the highest – self-actualization needs. A slightly modified and simplified model is that by Allardt; according to Allardt, people’s needs include standard of living (having), social relations (loving) and forms of self-actualization (being). Social relations include social networks and belonging to them is the basis of one’s identity and social existence. Social support is the term used for different forms of emotional and material support. The nature of social support is reciprocal. It can be support provided directly by one person to another or indirectly through the system or community.

Forms and levels of social support

Social support has two dimensions, a qualitative and a quantitative dimension. It can also be subjective and objective in nature. The quality of social support can be measured only by subjective assessments. When providing material support the quantitative aspect is more prominent (medicines an exception); in the other support forms the qualitative aspect (including timing) is more important than the quantitative aspect. Thus a small functioning support network is better than a broad but passive one.

Social support has been divided into primary, secondary and tertiary levels based on the intimacy of the social relationships. The primary level includes family and close friends, the secondary level includes friends, colleagues and neighbours and the tertiary level acquaintances, authorities, public and private services. Social support can be provided by a lay person (usually on the primary and secondary level) or a professional (usually on the tertiary level). Recently different organizations have started training courses for lay providers of support aiming at strengthening the second level of support. Social support has both direct effects on health and well-being and indirect stress-buffering effects on coping in stressful situations.

The research on the effects of social support on health goes back to the late 1940s and early 1950s. The first studies in this area showed that lack of social support exposes people to recurrent accidents, suicide and risk of catching tuberculosis. In the 1970s the emphasis was on relationships between social support structures and health in communities. It was shown that the lack of social support increases the incidence of coronary heart disease, mortality due to myocardial infarction and total mortality in the population. It has also been shown that social support is important in perceived health and in reducing hypertension. Social support also has a positive effect on physical, social and emotional recovery. It reduces the need for medication and speeds up symptom amelioration. The positive effects of social support in different stages of illness can be summarized as follows:

The side-effects to the patient of excessive social support or poor quality support may include increasing the passiveness of the patient, creating dependence, reducing self-confidence and self-esteem and causing feelings of shame and guilt.