Chapter 5 Pharmacy and public health

Introduction

Over the past 30 years, pharmacists have received wide recognition for their considerable knowledge, skills and expertise in dealing with medicine-related issues at the level of the individual patient. In contrast, they appear to have struggled with the concept of contributing to the wider public health agenda. Perhaps this has arisen because pharmacists are most comfortable operating in situations where they determine the agenda and their work is focused on tackling medicine-related issues. Working with other agencies as part of a multidisciplinary team to address population-wide public health issues is a relatively new challenge that requires additional knowledge and skills.

There is an irony to the current situation because for many years pharmacists have addressed a range of public health issues by giving lifestyle advice on issues such as smoking cessation, diet, substance misuse, sexual health, alcohol and exercise to the population they serve. Pharmacists have, however, generally failed to recognize these as public health interventions. Perhaps only in recent years has pharmacy started to recognize its public health contribution following the publication of key government strategies to develop public health pharmacy (Department of Health 2005). This chapter will help the reader better understand the principles of public health and the partnerships required to deliver the public health agenda and identify what the pharmacist can contribute.

What is public health pharmacy?

There are many definitions of public health in common use but perhaps the one most widely used in the UK is: ‘The science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society’ (Acheson 1998).

Central to this definition is the concept that promoting public health is not solely an evidence-based science. For those working within public health there is also a need to understand different sociological groupings within society and work with others to support and persuade the population or sectors within society to make changes that may bring health benefit. This can also be interpreted as promoting a ‘health service’ in which resources are expended on both encouraging people to adopt a healthy lifestyle and protecting them from communicable diseases. This is in contrast to an ‘ill health service’ that many feel the current healthcare system resembles and which primarily targets resources at those who are ill.

Typically, those employed in public health work across organizations such as local health service bodies, local authorities and local communities in settings ranging from acute hospital trusts and local health organizations through to local authorities, social services and the voluntary sector. Much of the work is long term and will take several years before any outcomes materialize that will have a lasting impact on health.

As a corollary to the definition of public health presented above, public health pharmacy can be defined as: ‘The informed application of pharmaceutical knowledge, skills and resources to promote public health’. This definition (Walker 2000) reflects a pragmatic approach to public health pharmacy and can be applied to whatever the preferred definition of public health is. This approach has proved useful to help understand what pharmacy can contribute but it has misled some to believe that public health pharmacy is a discipline in its own right. This is incorrect. Public health requires a multidisciplinary team approach and pharmacy is but one of the contributors, and often with a strong focus on medicine-related issues.

If pharmacy restricts its public health contribution to medicine-related issues, and given that taking a medicine is the most common intervention in health care, it will always be in a position to have some impact on public health. However, to influence the wider determinants of health is more challenging and requires an appreciation that more than 70% of what determines an individual’s health lies outside the domain of the health services and within demographic, social, economic and environmental conditions. To neglect these wider determinants will result in pharmacy failing to make its optimal contribution to public health. For example, there is limited opportunity to improve the health of a patient with asthma by counselling them on the correct use of their inhaler when wider public health issues are influencing treatment outcome. The individual may live in poorly heated, damp, infested accommodation, have a low paid job that involves working in a dusty or dirty environment, be poorly educated, have few or no friends or family to support them and have poor mental health. In addition, they may continue to smoke cigarettes, take little exercise and eat too many cheap, high fat content foods. It is clear that these factors will impact on good disease management, but the influential factors are often much less obvious than described above. To be aware of the wider determinants of health is important as each carries a significant health burden. Moreover, many health burdens have a significant link with deprivation. A number of these are summarized in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 Examples of indicators that have been shown to have a significant association with deprivation

| Domain | Indicator | Increased deprivation significantly associated with indicator |

| Lifestyle health determinant | Smoking | Yes |

| Excess alcohol consumption | No | |

| Healthy diet | Yes | |

| Physical inactivity | Yes | |

| Health status | Obesity | Yes |

| Physical functioning | Yes | |

| Bodily pain | Yes | |

| General health | Yes | |

| Vitality | Yes | |

| Social functioning | Yes | |

| Role – emotional | Yes | |

| Mental health | Yes | |

| Low birth weight | Yes | |

| Illness and injury | Depression and/or anxiety | Yes |

| Hearing | Yes | |

| Eyesight | Yes | |

| Limiting long-term illness | Yes | |

| Arthritis | Yes | |

| Back pain | Yes | |

| Respiratory disease | Yes | |

| Asthma | Yes | |

| Diabetes | Yes | |

| High blood pressure | Yes | |

| Heart disease | Yes | |

| Angina | Yes | |

| Heart failure | No | |

| Cancer registrations | Yes | |

| Pedestrian injury 4–16 years reported to police | Yes | |

| Pedestrian injury 65+ years reported to police | Yes | |

| Pedestrian injury 5–14 years hospital inpatient | Yes | |

| Use of health service | Dentist | Yes |

| Family doctor | Yes | |

| Hospital inpatient (persons) | Yes | |

| Coronary heart disease admission | Yes | |

| Angiography | Yes | |

| Revascularization | Yes | |

| Hip replacement | Yes | |

| Knee replacement | No | |

| Lens replacement | No | |

| Infant mortality | Yes | |

| Deaths | All-cause persons | Yes |

| All-cause females | Yes | |

| All-cause males | Yes | |

| All cancer | Yes | |

| Colorectal cancer | Yes | |

| Lung cancer | Yes | |

| Breast cancer | Yes | |

| Coronary heart disease | No | |

| Stroke | Yes | |

| Respiratory disease | Yes | |

| Unintentional injury | Yes | |

| Road traffic injury | Yes | |

| Unintentional fall | Yes | |

| Suicide | Yes |

Wider determinants of health

Most measures of population health show that it has improved markedly over the past 150 years. For example, life expectancy in England and Wales has improved in every decade since the 1840s. In 1841 life expectancy for males was 41 and this had increased to 75 years by 1998. The equivalent improvement for females was from 43 to 80 years of age. Much of the improvement seen has been the result of environmental and social changes rather than developments in medicine and health care. Despite these overall improvements, social inequalities have widened, with improvements in the health of the most disadvantaged groups being relatively small. To illustrate these inequalities we can look at the life expectancy of those who live in the most and least deprived areas of our big cities. In Scotland, for example, people living in the most deprived districts of Glasgow have a life expectancy 12 year shorter than those in the most affluent areas (NHS Health Scotland 2004). In London, boroughs a few miles apart have markedly different life expectancies. Each of the eight tube stations on the Jubilee line from Westminster to Canning Town represents a decline of one further additional year in life expectancy for the resident population (Department of Health 2004).

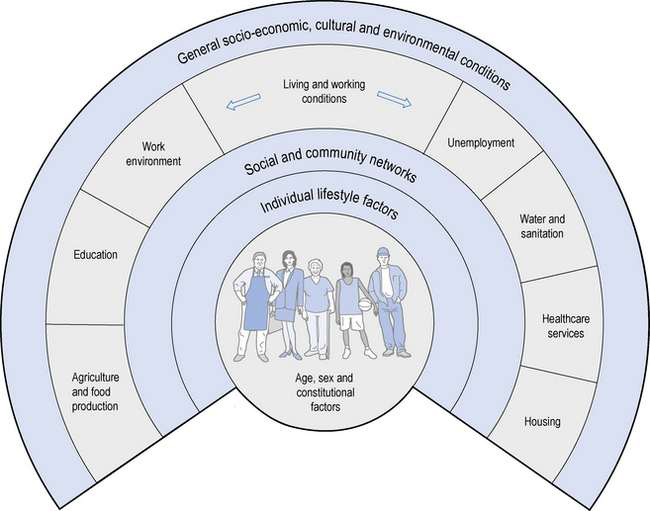

The landmark work of Dahlgren & Whitehead (1991) highlighted the main factors that determine the health of a given population (Fig. 5.1). The age, gender and genetic make-up of an individual clearly influence the health potential of that individual although each is fixed and non-modifiable. Other factors that influence health and which can be modified to have a favourable impact include addressing individual lifestyle factors such as smoking, diet and physical activity. Improving interactions with friends and relatives, and developing mutual support within a community can help sustain health. Other wider influences on health include living and working conditions, food provision, access to essential goods and services, and the overall socio-economic, cultural and environmental conditions. There are too many factors to discuss in detail here, but a number of the relevant, key determinants are outlined below. However, the simple message is that, whether attempting to evaluate mortality, morbidity or self-reported health, and regardless of whether it is income, class, house ownership, deprivation, social exclusion or similar indicator or combination of indicators that is used as the socio-economic indicator, those who are worse off in society have poorer health.

Employment and unemployment

Both employment and unemployment can be associated with adverse effects on health. Job security has also been recognized as important for well-being. The trend towards less secure, short-term employment affects everyone but is a particular problem for less skilled manual workers. Unemployment imposes a number of health burdens on the unemployed and some of these are summarized in Box 5.1.

In addition to job security there is considerable evidence that greater control over work is associated with positive health such as lower coronary heart disease, fewer musculoskeletal disorders, reduced mental illness and less sickness absence. The relationship between status in the workforce and health has been demonstrated across the gradient from the top jobs to those at the bottom. The landmark studies with civil servants in Whitehall, London (Marmot et al 1984, 1991) demonstrated that even those in the next grade down from the top had worse health than those in the top posts. Despite being in well paid and relatively secure posts, a health gradient was observed across a range of disorders when compared to those in the top posts.

A confounding issue when trying to interpret the effect of unemployment on health is that people with poorer health are more likely to be unemployed. This is particularly true for people with long-term conditions although this does not fully explain why the unemployed have poorer health.

Environment air quality

One of the most enduring images of poor air quality are the photographs taken in the 1950s of London in a dense smog. Pollution arising from the burning of domestic coal accounted for a significant number of premature deaths among Londoners. In the London smog of 1952 there was almost a threefold increase in death in the over 65s, while deaths from bronchitis and emphysema rose 9.5-fold, pneumonia and influenza increased 4.1-fold and myocardial degeneration increased almost threefold, along with associated increases in hospital admissions. Although the sulphur dioxide and black smoke from domestic coal is now a thing of the past, other pollutants have taken their place, notably from burning petrol and diesel in cars and other forms of transport. Ambient levels of air pollution continue to be associated with raised morbidity and mortality and are particularly hazardous to the elderly, children and those with pre-existing disease.

Crime

Crime affects not only the health of the victim but also that of the community involved. Fear of crime is a real phenomenon that impacts on both health and well-being. As a consequence of crime or the perception of crime, people make adjustments to their lifestyle and behaviour such as not going out after dark, not going out alone, avoiding certain areas, not using public transport and avoiding young people. Because crime is often concentrated in particular neighbourhoods and the avoidance measures outlined above are adopted, this can weaken social ties and undermine social cohesion in these neighbourhoods.

Energy and housing

It is recognized that energy obtained from fossil fuels must be reduced to meet international commitments on global warming and reduce their associated adverse impact on health. In many UK cities the trend is for falling use by industry but increased use by transport.

Heating of houses must also become more energy efficient. Typically housing for low income families is the most inefficient with the use of electric fires at standard tariff prices costing three times more than gas central heating. There is a fuel poverty strategy in the UK which seeks to provide heating and insulation improvement for those who spend 10% or more of their income on heating their home. Cold homes exacerbate many existing illnesses such as asthma and make the individual prone to respiratory infections (Box 5.2). In addition, fuel poverty brings opportunity loss. Poor families spend a disproportionate amount of their income in keeping warm and this has an adverse effect on their social well-being, ability to adopt a healthy lifestyle and overall quality of life.

Lifestyle determinants of health

The individual lifestyle determinants of health represent the areas in which pharmacy has traditionally made its most significant contribution to public health. It is therefore important to appreciate that poverty is associated with a number of behaviours that may have an adverse impact on health. For example, poor people are less likely to eat a good diet and more likely to have a sedentary lifestyle, be obese and abuse alcohol. Cigarette smoking has one of the strongest associations with social disadvantage, with higher levels recorded in more deprived sectors of the population, and this in turn has the greatest cost in terms of premature death.

Smoking

In 2006 tobacco smoking was the main avoidable cause of premature death in the UK, responsible for more than 120 000 deaths. Smoking causes a wide range of serious illnesses including cancer of the lung, respiratory tract, oesophagus, bladder, kidney, stomach and pancreas, respiratory disease including chronic obstructive lung disease and pneumonia, circulatory disease such as heart disease, strokes and aneurysms, and digestive disorders such as ulcers of the stomach and duodenum. Second-hand smoke also puts others at risk and has been linked to lung cancer, strokes, respiratory disorders and infections, particularly in children.

In 2007, before the introduction of the ban on smoking in public in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (smoking in public was banned in 2006 in Scotland), approximately 28% of men and 23% of women were smokers, accounting for up to 10 million people in England alone. This remains a significant problem despite the decline in smoking seen over the past 30 years from the 53% of men and 42% of women who smoked in the mid 1970s. Factors that continue to predict the likelihood of smoking include challenging material circumstances, cultural deprivation and stressful marital, personal and household circumstances.

To reduce the health burden of smoking, a number of public health strategies have been put in place and these include reducing the public’s exposure to second-hand smoke, providing more support for smokers to stop, raising public awareness of the health effects of smoking and the benefits of stopping smoking and reducing tobacco advertising and the impact of tobacco promotion, and regulating the sales and design of cigarette packets.

With respect to the no smoking agenda the major contribution of pharmacy is in raising awareness of the harm caused by smoking, supporting strategies to reduce the adverse impact of smoking on health, identifying smokers who want to stop and providing these individuals with behavioural support or referring them to alternative sources of smoking cessation support.

Pharmacists are often in a unique position to discuss smoking cessation and opportunities to raise the topic with individuals who visit them and who may be unhappy with their health, have respiratory problems or dental problems, be proactively seeking other lifestyle advice such as cholesterol or blood pressure testing, requesting health-related products such as cough medicines or alternative/complementary therapies such as St John’s wort, purchasing smoking cessation-related products or presenting a prescription for nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion or varenicline – all are potential windows of opportunity for pharmaceutical intervention.

Weight management

The UK is experiencing one of the world’s fastest growing rates of obesity. In 2006 obesity was considered to be at epidemic proportions with almost 24% of men and women classified as obese and 25% of children aged 11–15 years of age being overweight or obese. Such classification is often based on determining the body mass index (BMI: defined as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres) of an individual. A BMI in the range of 25 kg/m2 to 30 kg/m2 indicates the individual is overweight while a BMI of greater than 30 kg/m2 indicates obesity.

Being overweight can seriously affect an individual’s health and may lead to high blood pressure, type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease, many cancers including colorectal and prostate cancers in men and breast or endometrial cancer in women, osteoarthritis, poor self-image and decreased life expectancy.

Increasingly the measurement of waist circumference is being undertaken as it presents a simple way of assessing someone’s risk rather than measuring BMI. Men are at an increased health risk if their waist measurement is ≥ 94 cm and at substantially increased health risk if the measurement is ≥ 102 cm. Equivalent waist measurements for women are ≥ 80 cm and ≥ 88 cm.

Raising issues of weight management can be difficult but opportunities for the pharmacist to intervene may arise when a person complains of being unhappy with their weight, short of breath or having mobility problems associated with back or hip pain. Alternatively, opportunities may arise when individuals request products such as slimming aids, blood pressure monitors, cholesterol monitoring kits, alternative or complementary therapies for use in weight loss or receive prescribed or purchased medicines for arthritis, diabetes, cardiovascular or respiratory disease. Key advice to be offered will need to address healthy eating and exercise.

Alcohol

Excessive alcohol intake is associated with a range of health problems including serious liver disease, disorders of the stomach and pancreas, anxiety and depression, sexual problems, high blood pressure and cardiac disease, involvement in accidents, particularly car crashes, a range of cancers, including those of the mouth, throat, liver, colon and breast, and becoming overweight or obese.

Alcohol misuse currently accounts for approximately 22 000 deaths each year, with consumption above the recommended limits of 3 units per day for men and 2 units per day for women being exceeded by 22% of adult females and 39% of adult males. Of equal concern is the fact that 20% of the population in England drink to get drunk (binge drink). This is defined as consuming more than 8 units for men and more than 6 units for women and is strongly associated with involvement in accidents and with cardiovascular disease.

Most people are sensitive about revealing the details of their drinking habits; however, opportunities for pharmacists to raise awareness of sensible drinking may arise when individuals present with a hangover, headache, indigestion, or complain of insomnia, excessive tiredness, depression, stress, being overweight or report having been involved in a minor accident. Individuals seeking advice about testing blood pressure or dietary information, requesting products for hangovers, painkillers or antacids, and requesting kits to test drinks for contaminants also present opportunities for intervention. Requests for alternative medicines/complementary therapies that may be used to treat alcohol-related problems, or supplying a prescribed or over the counter medicine known to interact with alcohol are further opportunities that may allow discussion with the individual.

Exercise

Regular exercise for adults that is equivalent to at least 30 minutes a day of moderate physical activity on 5 or more days of the week, can help prevent or manage a range of disorders including cardiovascular disease, type II diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders, mental illness and a range of cancers. Children are required to undertake at least 60 minutes of moderate activity each day to promote healthy growth, development and psychological well-being. Recent surveys have shown less than 37% of adult men and 24% of women undertake sufficient exercise to gain any health benefit. Older people need to maintain their mobility and undertake regular daily activity, and attempts to improve strength, coordination and balance may be particularly beneficial.

Clearly the amount of physical activity an individual needs to undertake will be influenced by their daily routine and the nature of their job. Opportunities for the pharmacist to raise issues relating to physical activity may arise when people are unhappy with their weight, complain of being short of breath or tired, have mobility problems, suffer from depression or stress, or have difficulty sleeping. Again, when an individual seeks advice about monitoring blood pressure or cholesterol levels or requests dietary information on how to lose weight, it may be opportune to discuss exercise-related issues. Likewise the purchase of support equipment, for example for knees, requesting alternative or complementary medicines to provide energy, or obtaining prescribed or purchased medicines for blood pressure may be additional opportunities.

Measuring deprivation

Although a number of different approaches have been developed to measure the deprivation of a given population, most have significant limitations. Over recent years new tools have emerged to give more robust estimates of deprivation. One of the most widely used measures of deprivation has been the Townsend index, which produces a composite score for relative deprivation based on four variables obtained from the national census undertaken every 10 years in the UK. These variables include proportion of:

The Townsend index has a number of limitations, including a lack of validity in rural areas where, unlike urban areas, ownership of a car may be a necessity at all levels of deprivation. The Townsend index continues to be widely used because its construction is independent of health-related variables and the component data are captured in the national census. However, over recent years each of the constituent countries in the UK has developed its own approach to measuring deprivation. As a consequence it is increasingly difficult to compare deprivation across, for example, England and Wales. In England a new index was introduced in 2004 to measure multiple deprivation based on seven distinct domains:

From the above it can be seen that the Index of Multiple Deprivation 2004 is based on the principle of distinct dimensions of deprivation that can be recognized and measured separately. Individuals may be counted in one or more domains depending on the type of deprivation they experience. The final deprivation score is a composite, weighted score of each of the seven domains. In 2007 there were 354 local authorities in England and each could be given a score and a rank on the index of multiple deprivation. The lower the rank the more deprived the district.

In comparison to the English index, the Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation 2005 is compiled from seven similar indicators of deprivation: income, employment, health, education, housing, access to services and environment. However, the data sources utilized in the domains vary between the two countries and therefore the scores obtained cannot be used to compare deprivation in England and Wales. Even within a single country small differences in deprivation scores mean little and the scores do not really allow you to determine how much more deprived one area is compared to another. Likewise, where two areas have markedly different deprivation scores, one area may be considered less deprived than the other, but not more affluent, i.e. the indices are a measure of deprivation and not affluence.

Changing habits and lifestyle

To assist people in making changes to their habits and lifestyle there is a need to recognize the part played by socio-cultural influences and the environment. There are many models that are used to help understand the change process. One that has found use within public health is the ‘three Es model for lifestyle change’. In this model three stages are identified:

Encouragement involves raising awareness that may include the use of adverts, leaflets, one-to-one advice and targeted campaigns. This stage of the change process is used to act as a trigger for people to make healthy choices, or at least consider the healthy options. By itself, encouragement is unlikely to bring about sustained change in the population without empowerment and changes to environmental factors.

Empowerment involves the education and development of the individual and the community. Central to empowerment is the development of knowledge, life skills and confidence that will enable individuals, groups or populations to make the healthy choice. This process will be enhanced by the pharmacist, who can instil confidence in patients rather than undermining them, and by making changes to environmental factors.

Environment changes are targeted at the social, cultural, economic and physical surroundings in which people live and work. These changes aim to make the healthy choice the easy option.

A good example that can be used to illustrate this process is the need for the wider population to reduce their intake of salt to less than 6 g per day. Encouragement could involve a campaign to raise awareness of the daily intake of salt and the harmful effect of excessive intake; empowerment might target the labels on food and ensure they are easy for everyone to understand and to know what they are consuming; changes to the environment could involve a reduction in the salt content of prepared foods by manufacturers and the availability of low salt options in supermarkets and restaurants, thereby making it easier for consumers to reduce dietary salt intake.

Conclusion

This chapter has highlighted the key determinants of health and focused on areas of lifestyle advice where the pharmacist has traditionally contributed to the public health agenda. Hopefully it is apparent to the reader that to make a substantive contribution to public health, pharmacy will need to build on its current roles. Some public health pharmacy roles, such as assessing the health and social needs of communities through involvement in surveillance, surveys and information gathering exercises, acting as an advocate for local communities on health issues, and building sustainable communities or working in partnership with relevant statutory and voluntary services to promote and protect the health of the public, may be seen as roles best undertaken by individuals who choose to specialize in public health. Nevertheless, a large number of public health activities can be undertaken from a pharmacy, whether it is located in the community or hospital sector. Some of these are identified in Box 5.3.

Box 5.3 Examples of public health roles that could be undertaken by most pharmacies