Chapter 18 Formularies

Different types of formularies

Formularies were originally compilations of medicinal preparations, with the formulae for compounding them. The modern definition of a formulary is a list of drugs which are recommended or approved for use by a group of practitioners. It is compiled by members of the group and is regularly revised. Drugs are usually selected for inclusion on the basis of efficacy, safety, patient acceptability and cost. Drugs listed in a formulary should be available for use. Information on dosage, indications, side-effects, contraindications, formulations and costs may also be included. An introduction, giving information on how the drugs were selected, by whom and how to use the formulary, is usually provided.

The most common formulary in use in the UK is the British National Formulary (BNF), which compiles details of all the drugs available for prescribing in the UK. It is produced by the Joint Formulary Committee, whose members include doctors and pharmacists as well as representatives from the Department of Health. It is revised every 6 months and is issued to all prescribers and registered pharmacies in both hospitals and the community. Formularies for dentists, the Dental Practitioners’ Formulary, and for nurse prescribers, the Nurse Prescribers’ Formulary, are also included in the BNF. More recently a BNF for children was launched, in recognition of the need for different, more detailed information about prescribing in children.

Local formularies, or lists of recommended drugs, have been widely used in hospitals and increasingly in primary care throughout the UK for many years. Some are designed for small groups, such as one general medical practice, some are for all prescribers within a hospital; others may be intended for all prescribers within a large geographical area. The latter are often known as joint formularies, since they are compiled and intended for use by prescribers in both primary and secondary care. A recent survey found that 64% of primary care organizations have some sort of formulary and 47% are joint initiatives with secondary care. The increasing availability of a funded minor ailments service in community pharmacy, providing selected medicines free of charge to certain patients, has necessitated the development of formularies from which local pharmacists can supply the recommended products. Local formularies are usually developed and maintained by an Area Drug and Therapeutics Committee (ADTC). These committees involve pharmacists, hospital doctors, general practitioners and nurses who practise within a locality, and often also include management, public health and financial expertise.

Worldwide, formularies are a concept which is promoted by the World Health Organization (WHO). The essential medicines list (see Ch. 7) which is recommended as necessary for basic health care in developing countries is similar to a formulary. Any country can modify this list to meet its own particular needs and arrive at a ‘national formulary’. The basis of any list is that the drugs it contains are of proven therapeutic efficacy, acceptable safety and satisfy the health needs of the populations they serve. Some examples of formularies are given in Table 18.1.

Table 18.1 Examples of formularies

| Purpose | Example formulary |

| General use | British National Formulary |

| Hospital formulary | University College London Hospitals NHS Trust Formulary |

| General practice | Cambridgeshire Primary Care Trust Formulary |

| Joint formulary | Tayside Area Prescribing Guide |

| Lothian Joint Formulary | |

| Specialist formulary | Palliative Care Formulary |

| Developing countries | WHO Essential Drug List |

A formulary may be thought of as a prescribing policy, because it lists which drugs are recommended. Prescribing policies should, however, be much more detailed than a formulary, giving details of drugs which should be selected for use in specific medical conditions. Examples of prescribing policies in common use are antibiotic policies, head lice eradication policies and malarial prophylaxis policies.

Clinical guidelines contain more detailed information than a formulary about how a service should be delivered or patients treated and do not always specify the drugs to be used. Many are developed nationally, such as by the National Centre for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), British Thoracic Society, British Society for Haematology and so on. Local guidelines may be developed by ADTCs and are more likely to include recommendations which specify drugs included in the local formulary.

Benefits of formularies

Drug costs are a major component of the total cost of the NHS and are constantly rising. As the resources of the NHS are finite, it becomes increasingly necessary to contain the escalation in drug costs. Much evidence shows that drugs are not always prescribed appropriately. Therefore improving prescribing could reduce expenditure on drugs. Local formularies which recommend specific drugs and exclude others are one means of achieving this. Prescribing policies assist prescribers in using the drugs in a formulary and specific treatment protocols make them even more useful. Clinical guidelines help to ensure that the treatment of patients is based on evidence of best practice. Used together, formularies, clinical guidelines and treatment protocols can ensure that standards of prescribing are both uniform and high quality. All these are tools used to promote rational and cost-effective prescribing.

Rational prescribing

Prescribing which is based on the four important factors of efficacy, safety, patient acceptability and cost should be rational. While many drugs may be available to treat any particular condition, the process of selecting the most appropriate one for any individual patient should take account of all these factors, plus other patient factors, such as concurrent diseases, drugs, previous exposure and outcomes. The four factors can also be applied to selection of drugs to treat populations of patients and it is for this situation that formularies are developed. Providing drug selection is based on good quality evidence of efficacy and toxicity, formularies then assist in making decisions regarding individual patients.

Cost-effective prescribing

Formularies often provide information on the cost of products to help users to become cost conscious. Local formularies usually include only a small proportion of the drugs listed in the BNF, often between 200 and 500. If prescribers only use the range of drugs included in a local formulary, the range stocked by pharmacies can decrease, which reduces unnecessary outlay. Using a restricted range of drugs may allow pharmacists to buy these in bulk, further reducing costs. Formularies also encourage generic prescribing which may reduce costs even further. If fewer products are stocked, monitoring of expiry dates becomes easier and cash flow may improve. Any money saved on hospital or on GPs’ budgets by using a formulary may be used to benefit patients in other ways. For example, reducing the prescribing of drugs which have little evidence of therapeutic benefit, such as peripheral vasodilators, could enable more to be spent on lipid-lowering drugs. Formularies may also recommend using more cost-effective alternatives to some expensive modified-release formulations. In addition, as safety is also a key factor in drug selection, formularies may contribute to reducing the incidence of adverse drug reactions, which often carry a high cost.

Educational value

Compilation of a formulary involves researching the literature to gather evidence of efficacy and toxicity. For those involved, this is a highly demanding task, but one which is of considerable educational benefit. There are also benefits for users of formularies. Prescribers who use a restricted range of drugs should know more about those drugs and their formulations through frequent use. Ultimately this should result in benefits for the patient, as prescribers’ increased knowledge should reduce the risk of inappropriate prescribing, which could contribute to adverse effects, interactions or lack of efficacy.

Continuous care

A joint local formulary which covers both primary and secondary care encourages the same range of drugs to be prescribed, which makes continuing drug treatment across the interface easier. As patient packs are increasingly dispensed, patients are more likely to use their own drugs during a hospital stay. A joint formulary helps this, as there is less chance of drug therapy having to change to comply with a different formulary on admission to hospital.

Formulary development

Formularies take a very long time to produce: several years is not uncommon. Obtaining everyone’s opinions and discussing the drugs to be included are the main reasons, for this prolonged time. A formulary then needs to be updated regularly if it is going to be useful, which is a further time commitment. There are two basic ways of producing a new formulary – either start from scratch or modify an existing one. Adapting another formulary to suit local needs is much less time-consuming than starting from scratch. Although much can be learned from looking at someone else’s formulary, simply deciding to adopt it without any changes is not a good idea. Producing a formulary is an educational process, during which all concerned learn from each other’s experience and update their clinical pharmacology and therapeutics along the way. Producing a formulary also brings a sense of ownership, which encourages commitment to it and increases the chance of it being used. Local needs should also be addressed by a local formulary, so copying someone else’s may not be satisfactory.

A local ADTC is most likely to oversee the task of developing a formulary. Although the committee will include different healthcare professionals, pharmacists usually play a key role. Small subgroups of local experts may do most of the development work, but the opinions of potential users should also be sought. This is a very important point in formulary development. The people expected to use a formulary must have the opportunity to give their views on its content. If their opinions are not asked, they may feel that it does not apply to them and will be less likely to use it. Smaller formularies, such as for one general medical practice or ward, should be developed by all the prescribers working in that practice or ward together with a pharmacist. Such formularies may draw on the work of ADTCs and select even fewer drugs from the area formulary, but may add others. It is important that formularies reflect the needs of the population being treated. So obviously a formulary for a surgical ward will differ from that for a general practice, but both may be derived from the area formulary.

Content

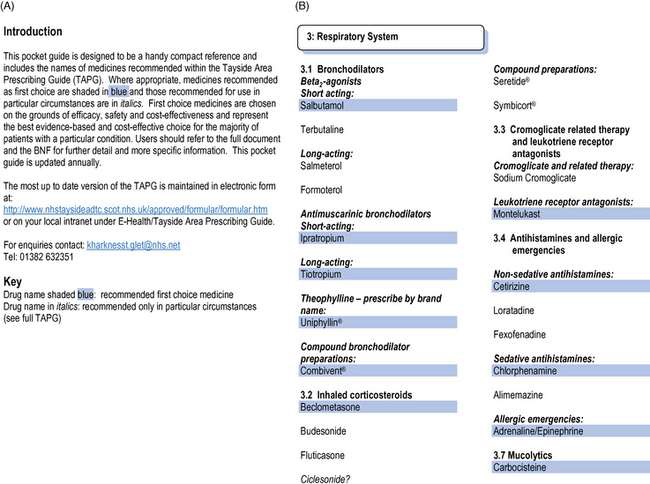

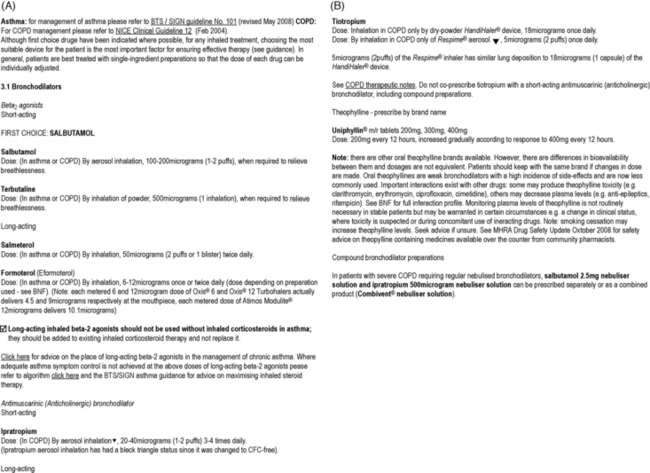

The formulary should start with an introduction, giving the names of those who have compiled it, stating who is expected to use it and explaining its format (Fig. 18.1). It is important to state whether all the drugs included are recommended for all users, and if not, how different recommendations can be distinguished. The BNF, for example, lists drugs the Joint Formulary Committee considers less suitable for prescribing in small type. The examples in Figures 18.1 and 18.2 illustrate how the recommended first choice drugs are highlighted. Local formularies may choose to place restrictions on some drugs, for use by specialists only, for certain indications only or in certain locations only. These drugs should also be easily distinguishable from the others in the formulary; in Figure 18.1 these are in italic. A list of contents and an index should be included to make the formulary easy to use.

Fig. 18.1 Formulary introduction and formulary recommendations for respiratory drugs, illustrating presentation as a Pocket Guide (reproduced with permission from Tayside Area Prescribing Guide Pocket Guide 2007, copyright: NHS Tayside Drug and Therapeutics Committee).

Fig. 18.2 Formulary recommendations for bronchodilators, illustrating presentation as a detailed prescribing guide (reproduced with permission from http://www.nhstaysideadtc.scot.nhs.uk/TAPG%20html/Section%203/3-1.htm).

Most UK formularies follow the BNF to classify medicines. Reference to the relevant BNF section is helpful if a local formulary is designed to be used in conjunction with it. Users can be directed to the monographs there for information on dosage, indications, side-effects, contraindications and precautions. Some formularies include all this information, but only for the recommended drugs. Other important information which may be given is local drug costs and the reasons for selecting the drugs included.

Drug costs are one of the factors taken into account when compiling a formulary (see below). The price of a drug can be expressed in several different ways. The prices given in the BNF are the prices of different pack sizes or for 20 doses of generics at drug tariff prices. The cost of a period of treatment may be more useful if comparisons are being encouraged. A suitable period may be 1 day, 1 month (28 days) or a standard course of treatment (e.g. 5 days for antibiotics). Since the price of the drug usually varies with the pack size, this may not be as easy to calculate as it first appears. A further complicating factor is the differing prices in hospital and community. If a formulary is designed to be used in hospital only, the hospital price may seem most relevant. However, the price of the drug may be different in general practice and patients may take the drug while living in the community for much longer than they take it in hospital. Therefore the price in the community is also of relevance, especially in joint formularies.

When large numbers of prescribers are to use a formulary, it is possible that not all of them will have been consulted about its content. If that is the case, providing explanations of how drugs have come to be included in a formulary is of particular importance. Many formularies state the general basis of drug selection as being efficacy, safety, patient acceptability and cost. Sometimes additional information is given about specific drugs, which can assist furthering drug selection. The BNF gives this type of information in introductory paragraphs to each section. An example is the statement that ‘other thiazide diuretics do not offer any significant advantage over bendroflumethiazide and chlortalidone’. It may be desirable to reference the formulary to give readers the opportunity to see the evidence on which statements such as these are based. It may also be useful to explain local preferences, particularly in the case of antibiotic selection, which should take local microbiological sensitivities into account.

Some or all of the formulary may be presented as prescribing policies. While this is most likely for antibiotics, policies may be included for any group of drugs. If this approach is taken, details of which drugs are to be used in specific medical conditions should be given. It may be necessary to include alternatives and the particular occasions when they should be used. In a prescribing policy, details of the recommended dosage, route and method of administration and duration of therapy should also be included.

A local formulary may have sections relating to prescribing in certain types of patients, such as the elderly, children, those with renal or hepatic impairment, or in pregnancy and breastfeeding. As there is little point in reproducing the BNF, these too should reflect local recommendations.

Presentation of a formulary

The appearance of a formulary is an indicator of the importance attached to it by those who have produced it. If it is presented on a few tattered sheets of paper, those who are expected to use it are unlikely to have a great deal of respect for its content. This may lead to poor adherence to its recommendations. It is therefore worth creating a document which is attractive and looks professionally produced. It is also important to consider whether a paper or electronic format is desirable or whether both should be available.

Paper formats can be portable, making for ease of use in any clinical setting, from the hospital bedside to the patient’s home. However, they are expensive to produce and still require regular updating. The size of the document is an important consideration. Ideally, it should be no bigger than pocket-sized, perhaps compatible in size with the BNF, to make it easy to use the two together. A simple list of formulary drugs is a useful option, such as that illustrated in Figure 18.1, produced by NHS Tayside Drug and Therapeutics Committee. This can be supplemented by a larger document in either paper or electronic form. If the formulary is only available as a large paper document which cannot be carried around, it is much less likely to be available when needed, which may mean its recommendations are ignored. Colour and a durable cover to withstand regular use can both add further to the appearance of a paper formulary, but also increase its cost.

Electronic formats are increasingly popular, but not all professionals use a computer when prescribing, so it may still be necessary to produce a paper version, even if this is only the list of drugs. A CD version is one option, but like a paper document, requires re-distribution whenever it is updated. Local organizations, such as hospital and primary care trusts, have an intranet, on which the formulary can be published. Linking the local formulary to electronic prescribing systems is perhaps the ideal option. Some prescribing systems incorporate decision support tools, which can include the formulary. Electronic versions may also make it easier to evaluate the formulary by examining prescribing adherence.

Ensuring that the formulary is up to date is extremely important and its presentation must allow for this. Loose-leaf binding will enable easy updating, but relies on everyone modifying their own copy. It is much easier to update an electronic version which is distributed via the Internet or intranet.

Whatever format is used, the formulary should be easy to use, to encourage prescribers to refer to it when necessary. This will be helped by a contents list, which for a paper version means the pages have to be numbered. Arranging the drugs in the same order as the BNF will also help to make the formulary easier to use, as prescribers should be familiar with this order. Using different typefaces and print size can make a formulary easier to use. Highlighting the drug names can be useful, as often the name of the recommended drug may be all that someone is seeking (see Fig. 18.1).

It may also be appropriate to provide access to the formulary for local patients. Increasingly, patients have access to clinical guidelines and are informed about what treatments are recommended for their medical problems. Providing a formulary has been developed using transparent methods and drugs selected on the basis of efficacy, safety, patient acceptability and cost, there is no reason to prevent patients from knowing of its existence. Access can be via the Internet, so need not add to publication costs.

Selection of products for inclusion

It is important to decide at the outset the range of indications which the formulary should cover. Some hospital formularies do not attempt to include drugs to treat all possible conditions. Some deliberately exclude certain drugs, such as those used in cancer chemotherapy and anaesthetics. These areas are extremely specialized, so drugs in these groups are never likely to be used by most prescribers. A formulary for use in general practice should aim to include enough drugs to treat between 80% and 90% of all common conditions which present to a GP. It is also useful to include emergency drugs, such as those which should be carried by GPs in their emergency bags. Clearly if a formulary includes all the available drugs, as does the BNF, it will not only be bulky, but also will not have many of the advantages that a local formulary can provide. It should be possible to cover most needs, either in hospital or general practice, with about 300–500 drugs. In selecting drugs for inclusion in a formulary, it is important to remember that recommendations are being made to treat the majority of the population. However, individual patients’ needs and preferences should, where possible, be taken into account. This means that there may be individuals for whom the recommended formulary drug is not suitable, but the formulary should attempt to make provision for most commonly encountered situations. This usually means that, out of the range available, two drugs from a pharmacological class may be included rather than one.

While the four important factors are efficacy, safety, patient acceptability and cost, other factors are also usually considered (Box 18.1). Formulary drugs must be effective for whatever indications they are to be used, with minimal toxicity. Evidence of efficacy should be based on well-conducted clinical trials rather than anecdotal reports. Generally, prescribers’ personal preferences are not a sound basis for selection of a particular drug or product. This is especially true when the formulary is to be used by many prescribers, as each may have their own preference. Occasionally there may be a range of similar drugs from which to select, but not all are licensed for all the indications the formulary is to cover. An example is beta-adrenoceptor antagonists, some of which have a range of licensed indications (Table 18.2). In this situation, selection of the drug which covers most indications may be appropriate. Alternatively, separate drugs could be selected for different indications. This option results in difficulties when auditing adherence, as it is impossible to tell from looking at prescribing data only whether the drug is prescribed in line with the formulary recommendations.

Table 18.2 Example using beta-adrenoceptor antagonists of how factors can be used to select drugs for a formulary

| Factor | Examples of information to be taken into account | Examples of possible selection |

| Licensed indications | For hypertension there are many to select from | Atenolol, propranolol, metoprolol, etc. |

| OR | For arrhythmias, few are licensed | Sotalol, esmolol |

| Evidence of efficacy | For secondary prevention of myocardial infarction | Atenolol injection, metoprolol, propranolol |

| For heart failure | Bisoprolol, carvedilol | |

| Toxicity | Water solubility results in less nightmares | Atenolol, sotalol |

| Intrinsic sympathomimetic activity causes less cold extremities | Oxprenolol, pindolol | |

| Contraindications | Cardioselectivity is preferable in asthma and diabetes | Atenolol, bisoprolol, metoprolol |

| Pharmacokinetic profile | Long-acting drugs/products require fewer doses | Atenolol, modified-release propranolol |

| Generic availability | Usually reduces cost | Atenolol, propranolol, metoprolol, bisoprolol |

| Acceptability to patients | Once-daily doses, combination products may be useful | Atenolol, co-tenidone |

| Cost | Cheapest preferable if all other factors equal | Atenolol, propranolol, metoprolol |

If two drugs are equally efficacious, as is often the case within a group of pharmacologically similar drugs, the least toxic one is preferable. Any differences between the drugs in terms of their pharmacokinetics, contraindications, adverse effects and potential for interaction then become important.

Pharmacokinetic profiles of drugs are important in selecting drugs with an optimum half-life for their indications. It may also be possible to select drugs which are minimally affected by either liver or renal impairment. Among the benzodiazepine group, for example, those with short half-lives and which have no active metabolites are usually preferred as hypnotics, as they have no hangover effect. Differences in drug handling in children and the elderly may require different drugs to be recommended for use with these patients. Selection of drugs for use in pregnancy and breastfeeding will be influenced by their passage into the placenta and secretion into breast milk.

The range of contraindications, precautions and adverse effects may differ for drugs within a therapeutic class. While class effects are common, sometimes there are differences between individual drugs; again beta-adrenoceptor antagonists are a good example of this. Differences are most often found in the frequency and severity of adverse effects between drugs in a class. Where possible, formulary drugs should have the lowest frequency of, and least severe, adverse effects.

If drugs are similar in terms of efficacy and toxicity but have different potential for interaction, this could be a deciding factor. Drugs with fewer possibilities of interaction mean fewer problems in use.

Patient acceptability is an important factor, which will be affected by efficacy and toxicity. If drugs do not work, or if they cause side-effects, patients are less likely to take them. For orally administered drugs, palatability and ease of swallowing will contribute to acceptability. Other considerations may also be important, such as the extent to which a dispersible preparation actually disperses, or whether a modified-release tablet can be divided. Inhaled drugs are available in many different formulations and their selection will depend to an extent on what patients will or can use properly, to achieve maximum efficacy. For topical products, such as creams and ointments, patient acceptability is particularly important.

A local formulary may simply list drugs which are recommended or it may specify particular dosage forms of those drugs. Patient acceptability is likely to influence the different formulations selected for inclusion in a formulary more than the drug entities. However, the range of formulations available, which will in turn affect patients’ acceptance of drug therapy, may be a factor in deciding which drugs to include. If a drug is available in a wide range of formulations, it may be a better choice than one which has very few. It is simpler for the prescriber to remember one drug name when a particular class of drug is required, rather than to have to choose different drugs because they come in different formulations.

Many formularies exclude all combination products which include two or more drugs in fixed ratio. This is because it is impossible to increase the dose of one drug without also increasing the dose of the other drug(s). Some patients may receive higher doses of one of the constituents than they require as a result. However, combination products are more favoured in primary care, where they are considered to improve patient compliance and also reduce prescription charges for the patient. Combination products may be useful if the pharmacokinetic characteristics of the components are compatible and it can be shown that patients require and obtain benefit from all the components individually, in the same ratio as the combination product. Unfortunately, very few combination products are used in this way. Their inclusion in a formulary will depend on local preferences and appropriate use will subsequently depend on individual prescribers.

Cost considerations are also important, but the aim of a formulary is to encourage rational and cost-effective prescribing, not primarily to save money. Cost-effective prescribing involves the use of the drug with the lowest costs which is also effective, has minimal toxicity and is acceptable to patients. The cheapest drugs may not be the most acceptable, or of adequate efficacy. For some groups of drugs, prescribing costs may actually rise as a result of using a local formulary, since the optimum drugs may be the most expensive. However, where efficacy, toxicity and patient acceptability are equal, cost should be the deciding factor in drug selection. As described above, both hospital and community costs of drugs should be considered when selecting drugs for a hospital formulary, as the bulk of the cost is likely to be borne by primary care. The purchase price of a drug may not be the only factor to be taken into account when considering costs. Pharmacoeconomic evaluations, which take account of the costs of the consequences of treatments, may also be necessary (see Ch. 19).

All drugs included in a formulary should be easily available, so ‘specials’, drugs available in hospital only, or on a named patient basis, should be avoided. Generic availability is a bonus, as it usually means costs are lower than for drugs which are only available as branded formulations. Most formularies specify that prescribing should be generic, where appropriate. The use of computer systems for prescribing, which automatically change prescriptions to the appropriate generic name, increases the proportion of generic prescriptions considerably. This should also reduce costs.

As part of their role in formulary development, pharmacists frequently provide unbiased information about any differences in efficacy, toxicity and cost between drugs. Some useful sources of information are the National Prescribing Centre in Liverpool or the Scottish Medicines Resource Centre in Edinburgh and Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin.

Use of prescribing data

All the factors mentioned so far can also be applied to the selection of drugs for individual patients. A further factor which may be considered when selecting drugs for populations is current prescribing habits. The main reason for this is that it is much easier to encourage use of a formulary if it involves few changes of habit. However, if the commonly prescribed drugs are not efficacious, or have a high incidence or severity of toxicity, it is better not to include them. Frequent use does not necessarily imply appropriate selection. Information about current prescribing is obtainable for either hospital or primary care prescribers. National databases on hospital prescribing are being developed, but prescribing data from computerized pharmacy supply systems are readily available which usually relate to wards or directorates. In primary care, data are available from the Prescription Pricing Division in England, Health Solutions in Wales, the Information and Statistics Division in Scotland and the Central Services Agency in Northern Ireland. The data can identify prescribing by an individual GP or by a practice.

From data on the frequency with which different products are prescribed it is usually possible to identify one or two drugs within each therapeutic class which account for the bulk of prescriptions. These should usually be considered for inclusion in a formulary, as little change in prescribing habits will be needed, providing they are efficacious and have minimal toxicity. It may be possible to include only these drugs in a formulary, or there may be a need for others to be included on a more restricted basis. If the commonly prescribed drugs are inappropriate on therapeutic grounds, alternatives may be required.

Formulary management systems

A formulary needs to be flexible and dynamic. A system must be devised which allows this. This is known as the formulary management system and it covers many other aspects of formularies.

Production, distribution and revision

Producing a formulary is a very time-consuming task which, although overseen by the ADTC, needs a driver to take responsibility for ensuring it is completed. Usually this is a pharmacist, who will be involved in collecting together the data on which the drug selection will be based (published evidence, prescribing data and expert or all group members’ opinions), drafting material, reaching agreement on the format(s) and design to be used and seeing it through to production. The ADTC should consider who will need a copy and how it will be distributed. For paper versions, photocopying is cheapest for small numbers and can still incorporate colour and be attractively bound for a professional appearance. However, if large numbers are required, printing becomes more economical.

Distribution by mail with a covering letter may be easiest for large numbers of people, but hand delivery, with verbal explanation, may help to encourage interest and therefore adherence to a formulary’s recommendations. Launching of a new formulary (or indeed a revision) can usefully be accompanied by a meeting to explain its aims, describe how to use it and encourage discussion of its contents. Leaflets advertising the benefits of using the formulary and educational material may be usefully developed to encourage prescribers to learn about why they should consider using it.

Electronic versions can obviously be easily distributed within an NHS trust, but require just as much supplementary information to encourage their use. Specialist IT support to ensure that the formulary can be integrated with electronic prescribing systems is a key factor in their successful use.

After all the effort which goes into producing a new formulary has resulted in the final document, the thought of revising it is likely to be far from popular. However, because of the time taken to produce a new formulary, it will soon go out of date. If this is allowed to happen, respect for its content will decline. Adherence to its recommendations may follow suit. Revision should therefore be considered even before the formulary is finished. The BNF is revised every 6 months, but most local formularies cannot hope to achieve a similar frequency, because of the amount of work involved. Annual or biennial revision should be aimed at and specified at the launch. As new drugs are coming onto the market all the time, even 6-monthly revision will not be adequate to keep a formulary up to date. Some system, therefore, needs to be devised to allow new drugs to be considered for inclusion.

Responding to the needs of practice

Change is the norm in the world of drugs. New drugs are constantly becoming available, old drugs are removed from the market, new clinical trials provide evidence for efficacy of existing drugs in novel indications and post-marketing surveillance provides constantly changing data on adverse effect profiles. An awareness of all the facts this generates is essential, so that the formulary does not go out of date and can respond to the changes. In implementing a formulary, patients must not be deprived of the benefits of new information and drugs. There will also inevitably be an occasional need for patients to receive treatment outwith a formulary’s recommendations, since a formulary cannot be expected to cover all possible situations. Methods are therefore needed to allow drugs to be considered for inclusion in the formulary, to allow drugs to be removed from the formulary and to supply non-formulary drugs when these are appropriate.

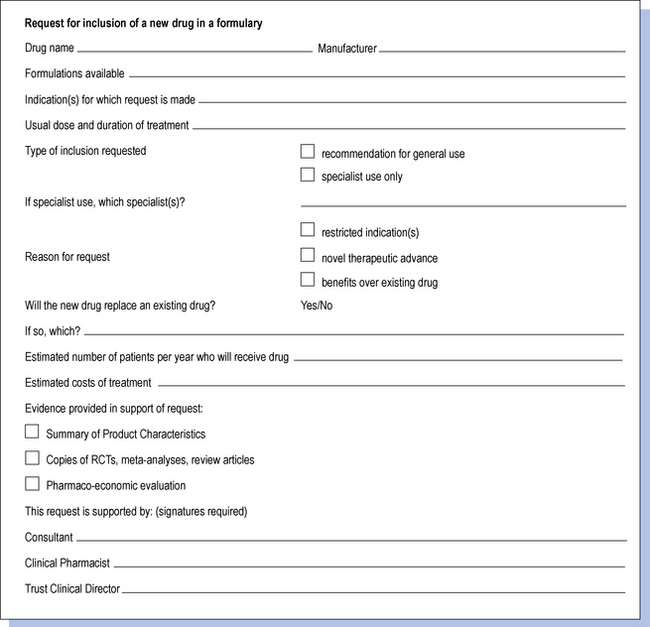

A method for allowing drugs to be considered for inclusion in a formulary should not be restricted to newly available drugs. It must allow any user of the formulary to propose a drug for consideration and should be able to provide an evaluated response within a reasonable time. Evidence of any advantages the proposed drug has over drugs already included, in terms of efficacy, reduced toxicity or cost, will be needed. This must be based on well-designed published clinical trials, the same basis as that used in the initial formulary development. Many formulary management systems require a form to be completed; an example is given in Figure 18.3. The person making the request must be informed as to whether the drug will be included and, if so, whether any restrictions will be placed on its prescribing. One option is to have an appraisal period, say 6 months, during which prescribers can gain experience with a newly recommended drug. After this period the committee can then review the status of the drug.

Fig. 18.3 Example of a form which could be used to request new drugs to be considered for inclusion in a formulary.

If a drug is accepted onto an existing formulary between revisions, it is essential to inform all users of the change. One way of achieving this is to issue information bulletins, either by post or e-mail. A similar method can be used to inform users of any changes in the indications or doses of drugs which may also occur during the life of a formulary. Similarly, if drugs are to be withdrawn from the formulary, users must be kept informed. Regular bulletins issued by the ADTC are therefore an important feature of formulary management.

Withdrawals may occur because of manufacturers ceasing production, product licences being withdrawn or changes in manufacturers’ recommendations. However, it may also be useful to consider withdrawing drugs from the formulary if they have not been prescribed for a long time. Again, 6 months would be a suitable time to study the prescribing of most drugs, except those whose use is seasonal. This could be done on a regular basis between major revisions, but would require consultation with prescribers before the withdrawal was implemented. The advantage of a practice such as this is that it helps to keep the number of drugs in the formulary to a minimum.

As there will be situations when a non-formulary drug is requested for a patient, it may be necessary to have a method of ensuring that the request is dealt with promptly. In primary care, there should be no problem in supplying a non-formulary drug, although there may be a delay if it is not stocked by local pharmacies owing to rare use. In hospital, however, pharmacies tend to stock only a limited range of drugs. Formulary drugs should always be easily available, but non-formulary drugs may need to be purchased specially. This will lead to delays in treatment. Some formulary management systems, usually in hospitals, require completion of a form for every non-formulary drug which is prescribed. The purpose of this is twofold: it acts as a deterrent to prescribing non-formulary drugs and also allows monitoring to see whether any drugs are frequently requested. Consideration may be given to including frequently requested drugs in the formulary. Usually forms require a senior medical staff signature, but there is a possibility that this requirement may be abused. Once a form with the appropriate signature is received, pharmacists should not simply assume that the request should be complied with. If this occurs, all that has been achieved is an elaborate ordering system. For the formulary system to operate effectively, all prescribers requesting a non-formulary drug should be questioned to determine the reasons why a formulary drug is not suitable.

One of the most frequent reasons for requesting a non-formulary drug in hospital is that the patient was taking the drug prior to admission and prescribers are reluctant to change it. This can be viewed as an opportunity to review the medication, ensuring that it is appropriate for the individual patient. If it proves to be so, it may be possible to use the patient’s own supply of the drug, providing there are systems in place to ensure this is indeed required and fit for use. If this is not an option, a decision must be made on whether the requested drug will be supplied from the pharmacy. The systems in place must ensure that this is a rapid process, particularly if a special purchase is required.

The most common reason for using non-formulary drugs in primary care is also that patients are already taking them and either they or their GPs are reluctant to change the prescription. Pharmacists can use the opportunity of conducting medication reviews to consider the appropriateness of any non-formulary drugs prescribed. Pharmacists also undertake regular review of repeat prescribing in many practices, using the techniques of drug utilization review, drug use evaluation and audit (see Ch. 19). Non-formulary prescribing can be assessed through these mechanisms and therapeutic switching undertaken to address any changes which would be of benefit.

The promotional activities of drug manufacturers’ representatives will need to be controlled to prevent them from undermining the principles of a local formulary. Many NHS trusts have policies on which staff representatives are allowed to see and what they are allowed to supply. Manufacturers can be an extremely useful source of information on their products, but the inclusion of a drug in a formulary must be evidence based and unbiased. Making constructive use of the visit from a pharmaceutical company’s representative can be a beneficial educational exercise to staff involved in using a formulary.

Clearly a lot of effort goes into operating a formulary and there are many advantages of a good formulary management system. The measure of success of any formulary is in the extent to which it is used or adhered to and the demonstration that prescribing is more rational. It may be possible to show improvements in efficacy and reduced toxicity and also cost savings, but these may be more difficult to achieve and to demonstrate.

Changing practice

Developing local formularies and treatment protocols encourages good relationships between prescribers and pharmacists. Building on this relationship is important to enable the changes to practice to be made which will be necessary in implementing these. Changing prescribing habits can be extremely difficult. Some prescribers dislike losing the freedom to prescribe as they choose and may reject a formulary and its concept. Often prescribers have developed personal drug preferences over the years and, even if they have no objection in principle to prescribing a different drug, may easily forget when actually writing prescriptions. Incorporating the formulary into electronic prescribing systems, which restrict choice or at least highlight formulary drugs as preferred, is therefore of great benefit. If agreement on what drugs should be used has been difficult to achieve, the resultant formulary may contain a large number of drugs. This can be more easily adhered to, but is less likely to achieve rational prescribing or to reduce drug costs. Conversely a formulary which is too restrictive is more likely to be difficult to adhere to.

When a formulary is introduced, some patients will be receiving medicines which are not included and they, too, may be resistant to change. The doctors who prescribe for these patients may also be unhappy about changing individual patients’ drugs. This is especially likely if the patient is well stabilized on a particular drug, with little adverse effects. As drugs included in a formulary will have been selected on a sound basis, it could be more suitable for a patient than their current drug. Change may therefore be of benefit. Education of prescribers and patients may be necessary to convince them of potential benefits and can be supported by educational packages, as already mentioned. Pharmacists are often those most actively involved in educating and persuading prescribers to carry out changes. They are also well placed to implement formulary recommendations themselves within their roles as prescribers. Even without changing individual patients’ drug therapy, if the drugs recommended in a local formulary are used for all patients starting new therapy, most prescriptions will in time include formulary drugs.

Research has shown that for clinical guidelines, visits to prescribers to provide education, involving local opinion leaders in educational meetings and interactive educational workshops are successful methods of changing behaviour. The same is likely to apply to formularies. A strategy should be developed which ideally includes a mixture of methods, because the more frequent the reminder, the more likely it is that practice will change. Constant reminders may be necessary to maintain prescribing within the recommendations of a formulary. However, feedback on adherence to the formulary is another important mechanism for reminding prescribers about it.

Auditing performance

Providing feedback to prescribers on whether they follow formularies is essential. Because formularies encourage rational prescribing, the extent of their use can be used as one indicator of the quality of prescribing. For other types of prescribing indicators, see Chapter 19. The simplest way to gauge whether a formulary is being used is to look at the same type of prescribing data used to help develop the formulary. Computerized prescribing data can easily be studied to assess whether formulary drugs are being prescribed. However, this type of data provides no information about the patients for whom the drugs have been prescribed. It cannot, for example, identify why patients have received prescriptions for non-formulary drugs. Nor can it be used to determine whether the formulary drugs were prescribed appropriately or whether formulary drugs were used within local guidelines or treatment protocols. For this, drug utilization review or clinical audit is required (see Chs 11 and 19).

For data to be of any use, they must be easy to interpret, accurate and up to date. They must also be of direct relevance to the prescriber to whom they are given and may allow comparison either to earlier prescribing or to the prescribing of others. Comparing the prescribing of several GPs or hospital doctors to each other is known as peer review. Comparison to a ‘norm’ of prescribing practice, or to the practices of others in the same peer group, often increases the desire of prescribers to conform to the ‘norm’ or the peer group. However, it is important to ensure that the ‘norm’ is desirable.

If hospital data generated by the pharmacy computerized stock control system refer to drugs issued to wards or directorates, care must be taken to determine whether this equates to drugs prescribed. Any drugs which were not issued through the computer system, such as patients’ own drugs, may not show up in these data. Electronically incorporating the formulary into prescribing systems should make the measurement of formulary adherence relatively simple.

In primary care, prescribing data represent the number of prescriptions dispensed, excluding only prescriptions written which have not been presented to pharmacies and dispensed. They cannot, however, distinguish between formulary and non-formulary drugs. This must be done manually and a figure for adherence can then be calculated, again taking the quantities of each drug into account. Another source of data in primary care is the practice computer, which can again incorporate formulary drugs within its programs. However, if a practice does not generate or record all its prescriptions via the computer, the prescribing patterns obtained will not show the full picture. The number of prescriptions written usually differs from those dispensed, so a different picture of formulary adherence may be found if data from dispensed and written prescriptions are compared.

When providing feedback to prescribers based on prescribing data, care should be taken to ensure that the quantities of the different drugs used are taken into account in some way. For example, if 180 tablets of a formulary drug and 20 tablets of a range of four other non-formulary drugs are used, adherence should be quantified as 90% (180 out of 200 tablets used in total). It could also be calculated that adherence was only 20% if the range of drugs were used (one out of a range of five), but this would not be a reasonable representation of the overall prescribing.

Another source of valuable data for the formulary pharmacist is the request forms for non-formulary drugs, if they are used. Review of these can indicate the extent of non-formulary prescribing. These should also explain the reasons why non-formulary drugs were used. Records of clinical pharmacists’ interventions made during routine prescription review or medication review which relate to non-formulary prescribing can also be studied.

Regular provision of information on performance is an essential part of formulary management. Any data which are presented to prescribers as a means of informing them of adherence to formulary recommendations will need to be attractive and easy to use, just like the formulary itself. Graphics and colour can be used to highlight important points. Finally, evidence of cost savings, if they have been achieved, may help to encourage use of the formulary. This is probably best expressed as actual expenditure compared to expected expenditure had the formulary not been used. If formulary adherence is found to be low, then this is an important result, which needs to be investigated to determine whether the formulary best serves the needs of the population or requires revision.

All this feedback should be provided in the same formats as the formulary – paper, electronic or both. It can be incorporated into regular published bulletins from the ADTC. This highlights the continuing importance of the formulary and should be an indication of the committee’s willingness to update the formulary in the light of changing needs. Pharmacists can also use discussion of feedback information as another opportunity to market a formulary and gain the support of prescribers in its use.