Chapter 22 Prescribing for minor ailments

Introduction

The community pharmacist plays an essential role in providing patient care. In most western countries, a network of pharmacies allows patients easy and direct access to a pharmacist without an appointment. Without pharmacists, general medical services would be unable to cope with patient demand. In effect, pharmacists perform a vital triage role for doctors by filtering those patients who can be managed with appropriate advice and medicines and referring cases which require further investigation. This has been a central role of community pharmacists for many decades, but over the last 20 years the role has taken on greater significance as there has been a shift in global healthcare policy to empower patients to exercise self-care. For pharmacists to safely, effectively and competently manage minor ailments requires considerable knowledge and skill. It involves having the underpinning knowledge on diseases and their clinical signs and symptoms, the ability to apply this knowledge to an individual patient and use problem solving to arrive at a working differential diagnosis. This has to be combined with good interpersonal skills such as picking up on non-verbal cues, asking appropriate questions and articulating clearly any advice which is given. This chapter attempts to provide the contextual framweork behind the growing prominence of the pharmacist in managing minor ailments and the key skills required to maximize performance.

The concept and growth of self-care

The concept of self-care is not new. People have always treated themselves for common illnesses and pharmacists have always provided an avenue for people to practise self-care. Self-care does not mean individuals are left on their own and means more than just looking after themselves. It includes all the decisions and actions people take in respect of their health and covers recognizing symptoms, when to seek advice, treating the illness and making lifestyle changes to prevent ill health. The expertise and support provided by healthcare professionals, such as pharmacists, is crucial to making self-care work. The profile of self-care has dramatically increased in recent years and is largely government driven, consumer fueled and professionally supported.

Government policy

The creation of national healthcare schemes, such as the NHS has encouraged the general population to become more reliant on institutional bodies to look after their health. This has led to increased demand on services provided by these bodies, including the management of minor illness. For example, more than one in three GP consultations are for minor illnesses and an estimated 20–40% of GP time could be saved if patients exercised self-care. Similar findings have been recorded for patients attending hospital emergency departments. This dependence by patients on bodies such as the NHS has led to government policies which encourage and facilitate self-care. In the UK, the government agenda for modernizing the NHS was spelled out in its White Paper The NHS Plan (2000). Within this document the government made its intention clear to make self-care an important part of NHS health care. It stated that the front line of health care was in the home. Since that time the government has published numerous papers detailing why and how maximizing self-care can be achieved. The prominence placed on this government strategy is evidenced by the Department of Health having a dedicated website on self-care (http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Policyandguidance/Organisationpolicy/Selfcare/index.htm). Included in these policy documents are specific papers looking at the role of pharmacy (e.g. A Vision for Pharmacy in the New NHS, 2003; Choosing Health through Pharmacy, 2005). It is clear that UK government policy centres on patient empowerment and utilizing all healthcare professionals to encourage patient self-care.

Widening access to self-care

The guiding principle of NHS modernization is to provide services that are best suited to the needs and convenience of patients. With regard to self-care, this can be achieved by encouraging patients to practise self-care themselves or by making better use of other healthcare professionals’ skills.

NHS walk-in centres and telephone help lines

The UK government has been proactive in facilitating self-care, most obviously by the formation of NHS walk-in centres and the telephone help lines NHS Direct (England and Wales) and NHS 24 (Scotland). The aim of walk-in centres is to improve access to health care that supports other local NHS providers. The service is nurse led but some employ doctors to work at particular times. The first NHS walk-in centre opened in 2000 and there are now approximately 90 operating in England. The Department of Health states that over 5 million people have used a walk-in centre with the main users being young adults. NHS Direct, launched in March 1998, has seen remarkable government investment and rapid and widespread expansion. It is a 24-hour nurse led service that receives over 500 000 calls per month. Although originally designed as a telephone help line service, NHS Direct now also offers an online service and direct interactive digital TV plus the publication of its self-help guide.

Deregulation of medicines

Less obvious, but arguably more important, has been the expansion of medicines available without prescription (Table 22.1). This has direct impact on community pharmacists and represents one of the major ways in which pharmacy can contribute to self-care. Widening access to medicines previously only available via prescription supply is a global phenomenon and not unique to the UK.

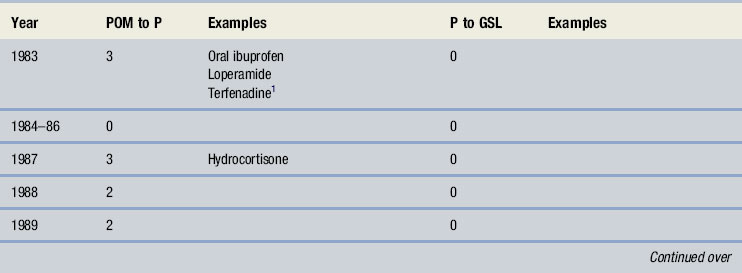

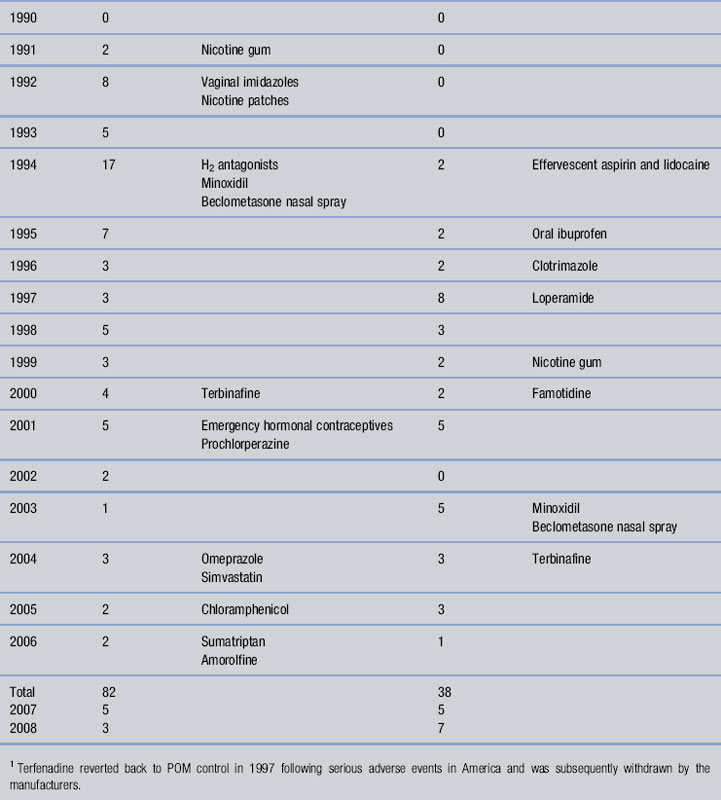

Table 22.1 Chronological history charting prescription only medicine (POM) to pharmacy (P) and P to general sales list (GSL) deregulation

The switching of prescription only medicines (POMs) to pharmacy (P) status is now well established. Loperamide and ibuprofen were the first POMs to be switched in 1983. The rate of POM to P deregulation after the initial two switches was slow, with only nine medicines deregulated between 1984 and 1991 (see Table 22.1). This was in part due to the bureaucratic process in place at the Medicines Control Agency (MCA; now known as the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Authority, MHRA). In 1992 the MCA changed the process by which medicines were deregulated. Under the new system, changes to the product’s legal status could be made without requiring amendments to the POM Order, thus speeding up the process. This change was effective, with no fewer than 30 medicines being deregulated over the next 3 years.

Further streamlining took place in 2002 to encourage manufacturers to switch medicines from both POM to P and P to general sales list (GSL). At approximately the same time, the White Paper Building on the Best (2003) set a target of 10 medicine switches each year (both POM to P and P to GSL) which was endorsed in The NHS Improvement Plan (2004). Between 1983 and 2008, over 80 POM to P and 40 P to GSL switches were made, although, the target of 10 switches per year from 2004 has yet to be met.

More recent POM to P switches have seen new therapeutic classes deregulated (e.g. proton pump inhibitors, triptans) and further deregulation of medicines from different therapeutic areas seems likely. The profession has played its part in this process, with the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (RPSGB) producing a consultation document on future candidates for POM to P switching (2002), some of which are now deregulated or being considered (e.g. tranexamic acid in 2007). Perhaps the largest area for future growth of deregulation centres on chronic disease management. Government policy toward self-care now embraces both acute and chronic illness (Supporting People with Long Term Conditions to Self Care: A Guide to Developing Local Strategies and Good Practice, 2006) and in 2004, the deregulation of simvastatin paved the way for further medicines to be available to manage chronic illness. This now enables UK consumers to purchase a medicine which government agencies have declared too low a priority to fund on the NHS (coronary heart disease risk of 10–15% over 10 years). This move therefore puts the emphasis squarely on the shoulders of the consumers to decide for themselves whether they want to initiate primary prevention.

Medical opinion on deregulation

Medical opinion is important in non-prescription use of medicines by patients. Doctors may advise patients to take them, prescribe them or dissuade their patients from using them. Relatively few studies have been conducted over the period of deregulation in the UK to ascertain GPs’ attitudes towards the move for greater access to previously POMs. Around the time of the first deregulated POM, loperamide, Morley et al (1983) found GPs were generally against potential switches. Not until 1992 was further work published on GPs’ attitudes to deregulation of medicines. Spencer & Edwards asked respondents their opinion on pharmacists managing 14 conditions treated at the time with POM medicines. Mixed results were found, ranging from the majority of doctors (87%) in agreement for pharmacists to use co-dydramol for toothache to almost no support (11%) for cimetidine to be given for dyspepsia. Erwin et al in 1996 and Bayliss et al in 2004 repeated the same questions. Over this 20 year period there is evidence that the attitudes of British GPs towards greater availability of medicines have become more positive. Bayliss et al hypothesized that this change in attitude is in part due to the length of time a product has been available without prescription and is supported by a 1999 Finnish study that found doctors were moderately positive, but more reserved towards those drugs only recently given over the counter (OTC) status. Results from all studies, except Bayliss et al, only considered acute conditions. When GPs were asked about management of chronic conditions, their opinions were strongly against such a move, yet opposition to the management of chronic illness might lessen in time, as it has with acute conditions.

Minor ailment schemes (MAS)

One barrier to patient self-care is the NHS system itself. Over 85% of prescriptions dispensed are exempt from the prescription charge (NHS statistics 2004). Therefore patients entitled to free prescriptions are likely to seek a doctor when they have minor illness, as any prescription issued will be free of charge in contrast to purchasing potentially the same product from the pharmacy. In response to this, a scheme dubbed ‘Care at the Chemist’ was established in Merseyside in 1999. It involved eight pharmacies and one GP practice and allowed patients free access to medicines through the pharmacy to treat 12 self-limiting conditions. Of the 1522 patients who used the scheme, only 21 patients were referred back to the GP. A 30% reduction in GP workload was observed for the 12 conditions included in the scheme. The scheme was subsequently replicated elsewhere and similar findings were observed. Consequently, the government called for widening participation of MAS, and the new pharmacy contract for England and Wales has seen MAS incorporated into the enhanced service specification and in Scotland it is included as a core service. MAS are designed to meet the needs of the local patient population. Consequently, different models exist throughout the country although many bear much similarity to the ‘Care at the Chemist’ scheme. However, there are some primary care trusts and health authorities that now use a common scheme and there is growing support for a national scheme to be implemented in England. In some schemes, patient group directions (PGD) have been incorporated to allow pharmacists to prescribe POMs to treat conditions such as urinary tract infections and impetigo. A useful resource is the National Prescribing Centre (NPC) website (http://www.npc.co.uk/mms/SIGs/minor_ailments/#HELP).

The public’s view on self-care and access to deregulated medicines

The public’s attitude toward self-care and its actual actions are contradictory. A King’s Fund study (2004) found that almost 90% of respondents believed they were responsible for their own health and a Mintel report (2004) found that 8 out of 10 people said they had to be ‘really ill’ to visit a doctor. However, it is estimated that upwards of 40% of GP time is spent dealing with patients who present with minor illness and only 25% of people who suffer minor illness self-treat with a purchased non-prescription medicine. It appears then that the government’s message on promoting self-care is understood by people but is not being translated into action. Of some comfort to the government are findings from 2003 and 2004 Mintel lifestyle surveys that show increasing numbers of people consulting a pharmacist while the number of GP consultations is slowly falling. These latter studies cite convenience as a major contributory factor to pharmacy consultation rather than waiting for a GP appointment. However, patient attitudes over being questioned before medicines are sold are seen as a barrier. A study by Morris (1997) found most consumers had a degree of awareness of why pharmacy staff might require information but almost two-thirds had expected to make their most recent purchase without being questioned. Cantrill et al (1997) also found that pharmacists reported more than 10% of consumers unwilling to answer questions.

It appears that some sectors of the public are unhappy to be questioned by pharmacy staff. This group poses difficulty for pharmacy staff but asking questions ensures responsible purchasing of OTC medicines by consumers. There is also a small body of research both in the UK and USA that indicates that the public regards OTC medicines as inherently ‘weaker’ than prescription medicines. OTC status in itself may lead to a perception that the medicine cannot be harmful. For example, 40% of people in a US study believed that OTC medicines were ‘too weak to cause any real harm’ (Roumie & Griffin 2004). That doses of medicines switched from POM to P may be lower than those used on prescription is likely to reinforce such beliefs and could influence why people believe that they should not be questioned.

Getting information from the patient

As healthcare professionals, community pharmacists are in a unique position. Patients have free and easy access to their advice. Not only do patients take advantage of this but they value it. Surveys have shown that the general public believes pharmacists to be one of the most trusted occupations. It is important that the faith the general public has in pharmacists is maintained and enhanced. Ensuring that you are competent to handle minor ailments is one way to do this. The following steps highlight the key considerations you should think about when someone asks for your advice about a particular symptom or condition they have.

First impressions

It is said that you never get a second chance to make a first impression. When we meet somebody for the first time we make assumptions about that person. We often put people into categories and the assumptions lead to expectations of their behaviour, jobs and character. This initial judgment of a person is often based purely on what we see and hear and includes appearance, dress, age, gender, race and physical disabilities. It is important that we are aware of these assumptions in order to avoid stereotyping people. For example, the impression we have of a person wearing a denim jacket may be very different from our impression of the same person wearing a suit. As you get to know a person better, initial impressions are either reinforced or discarded, but in the context of dealing with patients who want advice about minor illness, this could be the first and last time you see them. This first impression works both ways and pharmacists who create a friendly approachable impression are more likely to find patients receptive to what they say.

From the perspective of deciding what the patient’s problem is, this ‘first impression’ can be very helpful in giving you clues to their state of health. Assessment of the patient begins the moment the patient enters the pharmacy. Most pharmacists will probably do this at a subconscious level but what is important is to bring this to the conscious level and build it into your consultations. Many visual clues will be apparent if they are actively looked for. How old are they? Many conditions are age-related and this will help narrow down the number of conditions that need to be differentiated from one another. What is their physical appearance? Is the patient overweight or showing signs of being a smoker? Are there any signs of confusion, pain or systemic illness? For example, does the patient look well or poorly? For people who appear in discomfort or look visibly poorly, this might influence your decision to treat or refer – they might have a self-limiting condition such as viral cough but have marked systemic upset which necessitates referral. How did the person present to the pharmacy counter? Did they walk over in a normal manner or did they appear nervous, shy or reluctant? It might mean that the person who appeared nervous wants advice but is embarrassed to ask or they are intimidated by the environment and atmosphere. These ‘cues’ can be picked up by the pharmacist and appropriate action taken to make the person more at ease. The key is to observe your patient. Take time to assess what they look like, how they move and how they behave. This initial assessment will provide useful information which shapes your thinking and actions and is the first step to reaching a differential diagnosis.

Questioning

Arriving at a diagnosis is a complex process. In medicine it is based on three kinds of information: patient history; physical examination; and the results of investigations. Currently, physical examination and using diagnostic tests are rarely used in community pharmacy practice. Pharmacists rely almost exclusively on questioning patients when deciding whether to offer treatment or perhaps refer the patient for further evaluation. Studies have shown that an accurate patient history (gained from asking questions alone) is a powerful diagnostic tool. Supplementary examinations and diagnostic testing do improve the odds of reaching a correct diagnosis, but only by 10–15%.

The pharmacist’s diagnosis will, in many cases, be a differential one; the signs and symptoms are suggestive of a particular condition but it is difficult with absolute certainty to label the exact cause. For example, someone who presents with acute cough is likely to have a viral self-limiting cough but it could possibly be bacterial in origin. Advice and treatment might well be the same but an exact diagnosis cannot be made. Of course, in certain circumstances this can be done, for example head lice, eczema caused by a watchstrap or psoriasis on a knee, etc.

The ability to ask good questions to gain the appropriate information is therefore critical. The type of question and the way in which it is asked will dictate the level of response given.

Use of open and closed questions

There are two main types of questions: open and closed. A closed question is one which is direct and close-ended. It requires the respondent to give a single word reply such as ‘yes’ or ‘no’. They can be very useful when asking for specific information or to test understanding. Examples of closed questions are:

Open questions are open ended and allow people to respond in their own way. They do not set any ‘limits’ and generally allow the person to provide more detailed information. Open questions encourage elaboration and help people expand on what they have started to say. Examples of open questions include:

The above examples show that open questions are often built around words like ‘what’ and ‘how’ and generally allow an element of ‘feeling’ to be introduced by the patient in the reply. Open-ended questions are not without their problems. Some patients when asked an open-ended question will launch into a detailed explanation of their symptoms and it can be difficult to pick up on the important information that is mixed in with irrelevant facts. This can be time-consuming, which can make pharmacists reluctant to use open questions.

Choosing the correct type of question can prove to be difficult, particularly in a busy pharmacy where other patients are waiting for prescriptions or advice. It is tempting to ask a number of closed questions which will provide information, albeit limited to what can be gleaned from one word answers. However, this could result in the patient being ‘bombarded’ with many questions and make them feel as if they have been through an interrogation. Pharmacists must learn to develop good questioning skills to enable them to build up an accurate picture of the patient’s condition. In most consultations a mixture of closed and open questions will be needed. It also allows patients time to elaborate certain points and builds their confidence in the pharmacist.

As previously mentioned, how patients react to being asked questions in the pharmacy has been subject to some research. Findings have shown that some people feel it is not the legitimate business of pharmacy staff to ask what they may view as ‘personal’ questions about why the medicine is needed. It is therefore important to ensure that those people who are less responsive to being asked questions are dealt with in an appropriate way. This is usually done by explaining why questions have to be asked and using non-verbal communication. Position, posture and eye contact are important to give a relaxed, open appearance. Avoid using a counter or desk as a barrier or getting too close and invading a patient’s ‘intimate zone’ (see later).

Drawing together information

It is important that pharmacists are sensitive to the needs of their patients when asking questions. If the patient indicates they wish to speak privately or you notice they appear uncomfortable, then every effort should be made to provide a quiet area for conversation. With the new community pharmacy contract now in place, most pharmacies have consultation rooms which provide areas for this purpose. The pharmacist must tailor their questioning strategy to each patient. It is also important that each question is asked with a purpose. There is little point asking a question if nothing is done with the answer. A number of techniques have been advocated to maximize information gathering from patients. These include the use of acronyms, the funnelling technique and clinical reasoning.

Acronyms

Acronyms have been developed to help pharmacists remember which questions should be asked. WWHAM (Who is the patient? What are the symptoms? How long have the symptoms been present? Action taken? Medication being taken?) is the best known and simplest acronym to remember and has been advocated by many as a useful tool in gaining information from patients. Other acronyms have been subsequently developed and include ENCORE, ASMETHOD and SIT DOWN SIR. The difficulty with using acronyms is that they are rigid and inflexible – a ‘one size fits all’ approach. In addition, there is a tendency to ask questions for no reason – it is part of the acronym so the question has to be asked even though there might be no relevance or underpinning reasoning for asking the question. This is especially true of WWHAM, and because it is simple to remember it also means it provides the least information. Other acronyms do provide more information but because they are longer they become almost impossible to remember. Acronyms can be helpful in gaining some information from the patient but pharmacists should not rely solely on them. Each patient is different and it is unlikely that an acronym can be fully applied, and more importantly, it might miss vital information.

Current prescription workload and staff skill mix in most pharmacies makes pharmacist intervention in requests for advice or product selection impossible on every occassion. Up to 75% of patients are first seen by a counter assistant. The standardization of their questioning by using an acronym via a standard operating procedure (SOP) might be appropriate to ensure basic information is obtained from all patients.

The funnelling technique

A funnelling technique can be used to allow direction and focusing of ideas on a specific topic. This involves initially asking background open questions to provide basic information, then asking specific closed questions to provide specific detail and clarify points. In these circumstances, it can be useful to paraphrase comments made, to ensure that the understanding of the information being obtained from the patient is accurate. This checking procedure allows the pharmacist to check understanding and minimizes misinterpretation. It is possible during any one conversation to use more than one ‘funnel’, e.g. establishing a patient’s current medical condition, then going on to suggest appropriate action or medication available. In a pharmacy setting, where time can be a limiting factor, using the funnelling technique can be useful for directing and focusing a conversation to enable an end point to be achieved more quickly.

Clinical reasoning

Clinical reasoning relates to the decision-making processes associated with clinical practice. It originates from medicine in determining the best way physicians solve diagnostic problems. It is a thinking process directed towards enabling the practitioner to take appropriate action in a specific context. Based on these principles, the encounter with a patient in a community pharmacy is no different. It fundamentally differs from using acronyms or the funnel approach in that it is built around clinical knowledge and skills which are applied to the individual patient. Various models have been used to explain the process and include hypothetico-deductive reasoning and pattern recognition.

Hypothetico-deductive reasoning

This is a process in which a number of hypotheses are generated which are then used to guide subsequent information retrieval from the patient. Each hypothesis can be used to predict what additional findings ought to be present if it were true. Very early in a clinical encounter and based on limited information, practitioners will arrive at a small number of hypotheses. The practitioner then sets about testing these hypotheses by asking the patient a series of questions. The answer to each question then allows the practitioner to narrow down the possible diagnosis by either eliminating particular conditions or confirming their suspicions. Hypothesis generation and testing involves both inductive (moving from a set of specific observations to a generalization) or deductive reasoning (moving from a generalization to a conclusion in relation to a specific case). Therefore, induction is used to generate hypotheses and deduction to test hypotheses.

Pattern recognition

Pattern recognition relies more on inductive processes than deduction. For example, take a newly qualified pharmacist and a very experienced pharmacist who has been qualified 25 years. If they both see the same patient with the same problem, they both might arrive at the same conclusion, but how this was achieved will probably be different. This is because not all cases seen by more experienced practitioners will require applying a hypothetico-deductive model. For example, impetigo has a very characteristic appearance. Once a pharmacist has seen a case of impetigo, it is a relatively straightforward task to diagnose the next case by recalling the appearance of the rash. Therefore much of daily practice will consist of seeing new cases that strongly resemble previous encounters. For this reason, expert reasoning in non-problematic situations tends to be drawn from pattern recognition from previous stored knowledge and clinical experience.

Whether we are conscious of it or not, most people will use a combination of hypothetico-deduction and pattern recognition when dealing with patients. Neither model provides an error-proof strategy and error rates of up to 15%, especially in difficult cases in internal medicine, have been reported in the medical literature. However, these models of ‘responding to symptoms’ are more likely to gain the correct diagnosis compared to using acronyms and the funnel method because acronyms and the funnel method tend to just gather information without having a hypothesis in mind. Example 22.1 highlights the clinical reasoning approach.

Example 22.1

A man in his early sixties (slightly overweight) wants something for his cough.

Step 1: Visual clues: age, sex and overweight

Step 2: Conditions to consider

Based on epidemiology, the most likely cause of cough in any age patient is viral infection, yet many other conditions can cause cough. These can be categorized by their prevalence within the population and give the pharmacist clues to the magnitude of likeliness that the person will have that condition and should be borne in mind during consultation.

| Likely | Postnasal drip, allergies, acute bronchitis |

| Unlikely | Croup, chronic bronchitis, asthma, pneumonia, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor |

| Very unlikely | Heart failure, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis, cancer, pneumothorax, lung abscess, nocardiosis |

In this case our patient is approximately 60 years old so certain conditions can be eliminated (e.g. croup) and others are less likely (e.g. pneumothorax tends to occur in young people, heart failure and lung abscess tend to occur in the elderly). This leaves a possible 12 conditions which could present to the community pharmacy which have cough as the primary symptom.

Step 3: Formation of hypotheses

The initial question needs to narrow down the number of conditions that must be considered. A number of questions are relatively discriminatory, such as duration of cough, sputum production and presence of systemic symptoms. If we take duration (he has had the cough for 4 or 5 weeks) then this should eliminate acute causes of cough (up to 3 weeks’ duration) and leaves us with a list of nine possibilities, although three of these, post-nasal drip, allergy and medication, can be either acute or chronic:

A further hypothesis to test in Example 22.1 would now be sputum production. Knowledge of the conditions listed indicates that postnasal drip, allergy and medication are not associated with sputum production. As these are the three conditions which we have doubts over from the first question, it seems a good follow-up question to ask if the patient is producing sputum; if so, then these three conditions can be eliminated.

The patient tells you that there is a bit of phlegm but they haven’t really looked at the colour. This now means you are left with six possibilities. To differentiate between them, further distinguishing questions need to be asked. Some chronic cough conditions tend to show periodicity during the day, either being better or worse in the morning or evening. From our remaining conditions we know that generally:

Our patient says that the cough is always worse after getting up in the morning. This therefore tends to point to a diagnosis of chronic bronchitis. Obviously, the diagnosis is very tentative and we can now ask supplementary questions (generally closed questions) which should support the differential diagnosis. For example, our hypothesis would be that the person is a smoker or ex-smoker; we would expect them not to have any marked systemic symptoms; and we would expect that the person has a history of repeated episodes of cough. These confirmatory questions should be all positive and support our initial suspicions. If the patient responds in a different way to that which we anticipated then the differential diagnosis would need to be revised and hypotheses reconstructed to establish the cause of the cough. In this example the patient has to be referred.

This example illustrates the principle of hypothetico-deductive reasoning and the process behind it. In this instance, if an acronym, for example WWHAM, was used, the same outcome of referral would have been reached, as the ‘H’ question – how long have symptoms been present? – would have alerted the pharmacist to the chronic nature of the cough (all pharmacy text books on this area recommend referral for chronic cough). However, the information gained would have been superficial, which would not give you an idea of its cause and it would also ask irrelevant questions, such as who it was for (we already knew) and what medication they had tried.

For pharmacists, pattern recognition does play a part in shaping the above process but if the outcome is referral then clinical experience with the condition can be limited. Unless the patient returns or you follow up the case with the doctor, it is rare that pharmacists get feedback on the outcome of the referral. This therefore means that clinical experience of that symptom or condition is not consolidated by being given feedback on the diagnosis. Unfortunately, this means that if similar cases present again then pattern recognition can be used, but the level of knowledge remains at the same level as the outcome is always referral. Pharmacists should try to find out the outcome of referrals so that clinical experience increases and pattern recognition is improved.

Physical examination

Within the confines of a community pharmacy the type and extent of physical examination that can be performed is naturally limited and the majority of pharmacists will have received no formal training on how to conduct physical assessment. Examples of physical assessments that are suitable within the pharmacy include eye and ear examinations, assessment of skin disease and general inspection of the oral cavity. These examinations require little training but will improve the odds of making a correct diagnosis. This is one area where pattern recognition is very important – for example looking at a person’s skin rash will always be better than getting an explanation from the patient.

Picking up on non-verbal cues

The meaning of what a person says is made up of several component parts. These are the words which are spoken, the tone of voice used, the speed and volume of speech, the intonation and a whole range of body postures and movements. It is generally agreed that in any communication the actual words convey only about 10% of the message. This is called verbal communication. The other 90% is transmitted by non-verbal communication which consists of body language (about 50%) and how it is said (about 40%).

Body language

Body language can be broken down into several component parts which include gestures, facial expression, eye contact, physical contact, body posture and personal space. It is the combination of all these components which gives the overall impression. It is important to ensure that they are all compatible. If a mixture of messages is portrayed it will cause confusion to observers.

Gestures

Hand gestures in particular are useful when emphasizing a point or to help to describe something. Used appropriately, they can greatly enhance communication and improve understanding. Observing the patient’s gestures can give useful information on how concerned they might be or where the problem is. For example, someone presenting with abdominal pain might say they have stomach ache but point to the lower abdomen. In these cases, the non-verbal hand clue is much more informative than the spoken word. Also the person might point to a specific region, as the pain is very localized (e.g. appendicitis), or they might move their hand over a larger area (e.g. irritable bowel syndrome).

Gestures are also useful for the pharmacist to use as they can emphasize or reinforce a point or describe a particular procedure. However, it is important not to overuse them, as this can detract from the spoken word and become a distraction to the listener. Do some ‘people watching’. It is amazing how much information about people you can pick up just by quietly observing their gestures.

Facial expression

Facial expressions are a very important part of communication. Facial expression says a lot about mood and emotion, with the eyes and the mouth giving the dominant signs. As well as ensuring that facial expression is encouraging and welcoming, it is important for pharmacists to be able to read the meaning of facial expressions. In this way important points regarding a patient’s level of comprehension or receptiveness can be judged.

Eye contact

Avoiding eye contact is a very successful way of avoiding communication. This can be very well illustrated by observing a class of students who have just been asked a question by a lecturer!

The maintenance of eye contact during a conversation is vital to ensure the continuation of the process, because it indicates interest in the subject and is also useful as a means of determining whose turn it is to speak. However, care must be taken. Holding eye contact for too long can be off-putting and will reduce the success of the communication. Anyone who has been stared at will know how uncomfortable this can be.

Body posture

We can usually control the words we say, but it is more difficult to control our body language. It is possible, therefore, to send out mixed messages by having a positive verbal message but a negative body posture. This will only serve to confuse the patient and it is likely that the outcome of the interaction will be poor. There are several classic body postures which have been identified as having significant meanings:

Physical contact

This is an important aspect of any communication process and can be used to enhance verbal communication. A sympathetic touch on an arm can often say far more than any number of words. However, physical contact is governed by broad social rules which vary greatly between cultures. The British are identified as one of the least ‘touching’ nations, while in many cultures touching between the sexes is unacceptable. An awareness of this is important for pharmacists who will come into contact with people from a wide variety of social and cultural backgrounds. What is considered acceptable behaviour in one culture could be unacceptable in another.

Personal space

We all have our own space in which we feel comfortable. Personal space varies between cultures and its extent depends on the situation. An awareness of personal space is important for pharmacists as it can play an important role in the success or otherwise of communication. If you carry on a conversation with someone at too great a distance it may be difficult to build up any rapport. However, if you are so close to people that they feel uncomfortable and threatened, no meaningful dialogue will occur. The different space zones are generally divided into four main areas.

General area

This is approximately 3 m or more. This is the space we would normally prefer to have around us if we are addressing a group of people or are working alone.

Sociable area

This is approximately 1–3 m and is the type of distance used when communicating with people we do not know very well.

Personal area

This is approximately 0.5–1 m. This is the space we would normally feel comfortable with when at a business or social meeting with people we know reasonably well. It is sufficiently close to allow friendly and meaningful communication without any individuals feeling threatened by having their intimate zone invaded.

Intimate area

This is usually 0–50 cm. This space is reserved for people we know very well. Husbands, wives, children, close friends and family are examples of the kind of people with whom we would be comfortable at these distances. If anybody else enters this so-called ‘intimate zone’ we feel threatened and will generally withdraw into ourselves. However, this is the space that pharmacists must enter if they are to perform physical examinations. This is why it is essential that pharmacists, if performing an examination, must gauge the level of acceptance by the patient by asking permission to perform the procedure and explaining what is involved.

Vocal communication

Vocal communication, sometimes called paralanguage, concerns the vocal characteristics, the quality and fluency of the voice. The quality of the voice refers to the tone, pitch, volume and speed. Tone in particular can convey more meaning than actual words. ‘Thank you for asking the question’ said in a harsh voice contradicts the words and indicates that it is not meant. The same words in a warm tone show sincerity. The volume must be adjusted to the circumstances and can emphasize key words. The speed of speaking must enable the listener to understand. Varying the speed and pitch can make the words more interesting and hold the listener’s attention. Effective use of vocal communication requires that we become proficient at speaking with a warm confident tone of voice at an appropriate speed and volume and without interruptions or vocal mannerisms.

Outcomes from the consultation

The final step in prescribing for minor ailments is telling the patient what course of action you feel is most appropriate. This could be a combination of referral to another healthcare professional, giving advice or supplying a product. It is important that you give the patient as much information as they want or need and this draws on your skills of counselling (see Ch. 44).

Timescales

One of the key things a patient needs to know is what is the best course of action to take. Obviously this will depend on a number of factors including the patient themselves, the differential diagnosis and the severity of the condition. As a general rule, all patients should be advised on a timescale when they need to consult further medical help, whether they return to the pharmacist or see another healthcare practitioner. This allows the patient to understand the nature of the problem and know when they should seek further help. This will have to be gauged on a person-to-person basis. For example, take three patients all presenting with viral cough. Although the condition is self-limiting the timescales given to each patient can vary. If the first person presents after 7–10 days then you might tell them to see the doctor in the next 5–7 days if symptoms do not improve. The second patient has only had symptoms for 2 days, in which case you would give them a longer timescale. The third person might have had symptoms for 5 days but compared to the first two patients they have severe symptoms which would warrant automatic referral for a second opinion. This process is known as a conditional referral.

Treatment and advice

Once a full assessment of the symptoms has been made, and a decision made that the patient does not require immediate referral, appropriate recommendations should be made. Selection of an appropriate treatment for a condition involves application of pharmacology, therapeutics and pharmaceutics knowledge. The first step will be to choose an appropriate therapeutic group to recommend. The next step would be to assist the patient in the choice of product within the therapeutic group. For many therapeutic groups there is a wide variety of products available, often in various combinations. The pharmacist should take into account the efficacy, potential side-effects, interactions, cautions and contraindications. With regard to efficacy, pharmacists should be aware that many OTC medicines have little or no evidence base. This does not necessarily mean they are not effective, but in today’s climate of evidence-based health care then products with proven efficacy should constitute first-line treatment.

The difficulty in establishing efficacy has many explanations and includes: products that are available OTC predating clinical trials, a general lack of trial data or poorly conducted trials, the placebo effect seen with some OTC medicines and the nature of self-limiting conditions – is it the medicine working or the symptoms resolving on their own? Despite this, patient demand for a medicine to treat their symptoms is strong. Recommending an OTC medicine despite inadequate evidence of its efficacy is justifiable because many patients have a desire to try something to give them symptomatic relief. A negative or dismissive response by the pharmacist to a request from a patient can be harmful in that such patients may lose faith in the pharmacist and exercise self-care elsewhere where there is no qualified person to assess their symptoms. When selecting a product, the patient’s needs should be borne in mind. Factors such as prior use, formulation and dosage regimens should be considered. For example, antacids are available in both tablets and liquid form. Liquids tend to have a quicker onset of action than tablets but can be inconvenient for a patient to carry around with them or take to work.

Non-drug treatment should also be offered where appropriate. For example, providing medication for motion sickness can be supplemented with advice on how to reduce symptoms, for example focusing on distant objects, not overeating before travel or sitting in the front seat in car journeys will help to reduce symptoms. Advice on increasing dietary fibre and fluids is an essential part of the management of conditions such as constipation and haemorrhoids. Certain situations where pharmacists are being consulted by patients for advice on symptoms are ideal opportunities to promote health education (see Ch. 5). For example, someone who is asking for advice about a cough could be asked about their smoking habits.

Children and the elderly

These two patient groups have the highest usage of medicines per person compared with anyone else. Care is needed in assessing the severity of their symptoms as both groups can suffer from complications. For example, the risk of dehydration is greater in children with fever or the elderly with diarrhoea. Invariably, lower doses are used in children, and because the elderly suffer from liver and renal impairment they frequently require lower doses than younger adults. Children should be offered sugar-free formulations to minimize dental decay and elderly people often have difficulty in swallowing solid dose formulations. It is also likely that the majority of elderly patients will be taking other medication for chronic disease and the possibility of OTC–POM interactions should be considered.

Pregnancy

The potential for OTC medicines to cause teratogenetic effects is real. The safest option is to avoid taking medication during pregnancy, especially in the first trimester. Many OTC medicines are not licensed for use in pregnancy and breastfeeding because the manufacturer has no safety data or it is a restriction on their availability OTC. Table 22.2 highlights those medicines where restrictions apply.

Table 22.2 Medicines to avoid during pregnancy

| Medicine | Advice in pregnancy |

| Antihistamines – sedating | Some manufacturers advise avoidance, although chlorphenamine and triprolidine are classed by Briggs et al1 as being compatible |

| Antihistamines – non-sedating | Manufacturers advise avoidance as limited human trial data, but animal data suggest low risk |

| Anaesthetics – local (benzocaine, lidocaine) | Avoid in third trimester – possible respiratory depression |

| Bismuth | Manufacturers advise avoidance |

| Crotamiton (e.g. Eurax) | Manufacturers advise avoidance |

| Fluconazole | Avoid |

| Formaldehyde (e.g. Veracur) | Manufacturers advise avoidance |

| Ocular lubricants (e.g. hypromellose, carbomer) | Manufacturers advise avoidance as safety has not been established |

| H2 antagonists | Avoid |

| Hyoscine | Manufacturers advise avoidance as possible risk of minor malformations |

| Migraleve (opioid component) | Avoid in third trimester |

| Iodine preparations | Avoid |

| Midrid | Avoid |

| Minoxidil (e.g. Regaine) | Avoid |

| Monphytol paint | Manufacturers advise avoidance |

| Posafilin | Avoid |

| Selenium (e.g. Selsun) | Manufacturers advise avoidance |

| Systemic sympathomimetics | Avoid in first trimester as mild fetal malformations have been reported |

1 Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Yaffe SJ 2008 Drugs in pregnancy and lactation: a reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk, 8th edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia. (This is one of the standard reference texts used by medicine information centres in answering medicine suitability during pregnancy.)

Interactions of OTC medicines with other drugs

Medicines that are available for sale to the public are relatively safe. However, there are some important drug–drug interactions to be aware of when recommending OTC medicines. These are listed in Table 22.3.

Table 22.3 Interactions of OTC medicines with POMs that can be significant

| Medicine | Possible interactions | Outcome |

| Antihistamines – sedating | Opioid analgesics, anxiolytics, hypnotics and antidepressants | Increased sedation |

| Antacids (containing calcium, magnesium and aluminium) | Tetracyclines, quinolones, imidazoles, phenytoin, penicillamine, bisphosphonates, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II | Decreased absorption |

| Aspirin | NSAIDs and anticoagulants | Increased risk of GI bleeds |

| Methotrexate | Reduced methotrexate excretion, toxicity | |

| Bismuth | Quinolone antibiotics | Reduced plasma quinolone concentration |

| Chloroquine | Amiodarone, sotolol, antipsychotics | Increased risk of arrhythmias |

| Fluconazole | Anticoagulants | Enhanced anticoagulant effect |

| Ciclosporin | Increased ciclosporin levels | |

| Carbamazepine and phenytoin | Increased levels of both antiepileptics | |

| Rifampicin | Decreases fluconazole levels | |

| Atorvastatin | Increased atorvastatin levels that can lead to muscle pain/myopathy | |

| NB: Seriousness of the possible outcome would mean it is good practice to avoid all statins with fluconazole | ||

| Hyoscine | TCAs, and other medicines with anticholinergic effects | Anticholinergic side-effects increased |

| Ibuprofen | Anticoagulants | Enhanced anticoagulant effect |

| Lithium | Reduced lithium excretion | |

| Methotrexate | Reduced methotrexate | |

| Opioid-containing products | Alcohol, opioid analgesics, anxiolytics, hypnotics and antidepressants | Increased sedation |

| Prochlorperazine | Alcohol, opioid analgesics, anxiolytics, hypnotics and antidepressants | Increased sedation |

| St John’s wort | Anticoagulants | Reduced anticoagulant effect |

| SSRIs | Potential serotonin syndrome | |

| Phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine | Reduced antiepileptic serum level | |

| Oral contraceptives | Reduced efficacy of contraceptive | |

| Antivirals, ciclosporin, digoxin | Reduced plasma concentrations | |

| Systemic sympathomimetics, including isometheptene (ingredient in Midrid) | MAOIs and moclobemide | Risk of hypertensive crisis |

| Beta-blockers and TCAs | Antagonism of antihypertensive effect | |

| Topical (nasal or ocular) sympathomimetics | MAOIs and moclobemide | Risk of hypertensive crisis |

| Iron salts | Tetracyclines, quinolones, penicillamine | Reduced absorption if taken at same time |

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; GI, gastrointestinal; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

Providing advice (patient counselling)

The service specifications of the pharmacists’ Code of Ethics provides some guidance on the content of the counselling role of pharmacists. The specification on the supply of dispensed medicines states ‘Pharmacists must ensure that the patient receives sufficient information and advice to enable the safe and effective use of the medicine’. The sale of OTC pharmacy medicines is similarly covered by the service specifications and the pharmacist is required to provide ‘advice relevant to the product and the intended customer’.

Counselling should take place in a thoughtful, structured way. Pharmacists must have the ability to explain information clearly and unambiguously and in language the patient can understand. The counselling process should not be a monologue by the pharmacist giving a long list of information points. To be successful, it must be a two-way process. There should be ample opportunity for the patient to ask questions. Rapport is built up between the pharmacist and the patient and a much more meaningful dialogue can take place. What information to give to the patient will vary from case to case and will depend on a number of factors such as prior use and knowledge, the age of the patient and their comprehension level. However, as a general summary, patients should know:

Aids to counselling

Patient information leaflets, warning cards and placebo devices are all useful aids when giving advice to patients. Most OTC medicines provide product information, often as a patient information leaflet (PIL). These PILs, where appropriate, can be used during counselling and important points highlighted. Placebo devices, e.g. inhalers, drops, patches, etc. can be used to demonstrate a particular administration technique and also to check a patient’s ability to use the product. Leaflets on how to use ear drops, eye drops, eye ointment, pessaries, suppositories, etc. are available. Having given the information, it is then of major importance to check if the counselling has been successful. What does the patient understand, and do they have any problems? Watching the patient’s body language and maintaining eye contact can give useful clues as to whether the message is being understood and whether compliance is likely.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the pharmacist plays a pivotal role in helping patients exercise self-care and provides an effective screening mechanism for doctors. The continued deregulation of medicines to pharmacy control will mean that pharmacists over the coming years will be able to prescribe more medicines from more therapeutic classes. This necessitates that all pharmacists have up-to-date clinical knowledge and can competently perform the role. This might require many to acquire new skills (e.g. physical examinations) and take a much more active role in monitoring and following up the patient after advice and products have been given.