Chapter 37 Inhaled route

The role of the pharmacist

Inhaled products are specialized dosage forms, which are designed to deliver medicines directly to the lung. A variety of inhaler devices are in use, all of which require the user of the inhaler to adopt an appropriate inhaler technique. Failure to use the correct inhaler technique will result in treatment failure. The pharmacist, who is usually the person who gives (dispenses) the inhaler to the patient, is ideally placed to demonstrate the appropriate inhalation technique for that inhaler. Using an inhaler is a skill subject to the development of ‘bad habits’ which can lead to poor technique. Inhaler technique should therefore be regularly checked to ensure that the technique is optimal; again the pharmacist is ideally placed to perform this function.

Pharmacists can also provide education to patients beyond a discussion of a patient’s inhalers and other medicines, to include education about the patient’s disease (e.g. asthma) and its management. Pharmacists also run asthma clinics and may do so as supplementary or independent prescribers. A few pharmacists have specialist respiratory consultant posts in secondary care. A pharmacist wishing to undertake a specialist role in respiratory medicine will need to gain appropriate experience and undertake further training such as that offered by the National Respiratory Training Centre, Warwick.

This chapter describes the most frequently prescribed inhaled therapies in the context of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The most widely prescribed inhaler devices are outlined along with instructions in their use.

Introduction

Many patients on inhaled therapy will be using more than one inhaler and may also have been prescribed a peak flow meter (PFM) to aid in monitoring their condition. In order for pharmacists to be able to provide useful education and advice to these patients, pharmacists will need to understand the condition being treated and the role of the medicines and devices prescribed. This chapter will provide that understanding in the context of the two most common airways diseases treated with inhaled medicines, namely asthma and COPD. It is beyond the scope of the chapter to discuss the diseases themselves, or the role of oral therapy and non-drug management of these conditions (see Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, Walker & Whittlesea 2007). It should be remembered that the most important intervention in COPD is smoking cessation, and that oral steroids can be life-saving in acute severe asthma.

There are significant differences in the way that inhalers are prescribed for asthma and COPD. In COPD the emphasis of treatment is on the use of bronchodilators, and it may be appropriate for a COPD patient to have a long-acting inhaled beta-agonist without an inhaled steroid. This is different from asthma treatment where a long-acting beta-agonist should always be prescribed with an inhaled steroid. The scope of this chapter is limited to commonly used inhaled treatments and devices used for these inhaled treatments. By being familiar with national treatment guidelines for asthma and COPD, pharmacists can be assured that the advice that they give patients is likely to be consistent with that given by other healthcare professionals. These guidelines are widely available, e.g. in the British National Formulary (BNF) or at http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/ and click on ‘By subject’ then ‘Respiratory Medicine’ for asthma guidelines, and http://guidance.nice.org.uk/cg12 for COPD guidelines.

Asthma is a very common condition in the UK, affecting at least 5% of adults and up to 20% of children. It is therefore likely that 1 in 5 of the population will experience symptoms attributable to asthma at some time in their life.

COPD has been an under-publicized condition. Prevalence in 40–70-year-olds in the USA is estimated at around 10% and prevalence is likely to be similar in the UK. The decline in lung function leading to COPD is age related but this decline can be rapidly accelerated in some smokers. COPD is thus an increasing problem in an ageing population.

Asthma and COPD are not mutually exclusive and some patients will have features of both diseases; this is often referred to as ‘mixed disease’.

The prevalence of asthma, COPD and related conditions means that pharmacists will not only frequently be encountering patients on inhaled therapy during dispensing, but will also encounter patients on inhaled therapy when giving advice on the sale of over the counter medicines. This chapter not only provides pharmacists with the knowledge to confidently discuss with patients their use of inhaled therapy but also to be aware of some signs and symptoms that may be associated with poor disease control.

The inhaled route

The inhaled route delivers medicines to the lungs. Inhaled medicines may have a local effect on the lungs, or may be absorbed to give a systemic effect. The inhaled route is generally used when the lung is the target organ, e.g.:

Using the inhaled route when the lung is the target organ has a number of advantages:The main disadvantage of the inhaled route is that inhaling a drug is more difficult than swallowing a tablet. Some drugs are ineffective by the inhaled route, e.g. theophylline.

Using the inhaled route does not result in the entire quantity of drug in the inhaler device reaching the lung. Even if an inhaler device is used perfectly, it is unlikely that any more than 20% of the drug reaches the lung. The majority of the rest of the drug remains in the oropharynx and is normally swallowed.

The lungs are designed to prevent the inhalation of anything other than gas. However, particles with a diameter of approximately 5 μm can be inhaled and have sufficient mass to settle in the lung. Particles larger than 10 μm remain in the oropharynx. Particles smaller than 1 μm are inhaled, but are then exhaled. Decreasing particle size increases the chance of penetration further down the tracheobronchial tree. It may be that a particle needs to be less than 3 μm to reach the 8th to 23rd branch generation. These particle sizes apply to the adult lung, and a smaller particle size of the order of 2.5 μm may be optimal in infant lungs.

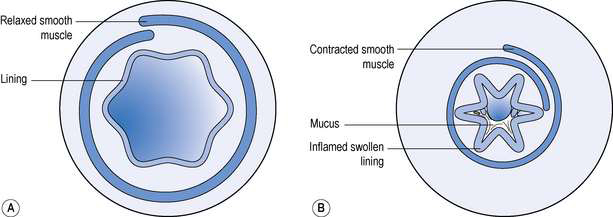

The specific target in the lung for medicines used in asthma and COPD is the bronchiole. Branching from bronchi, bronchioles are the first airways in the lung not to contain cartilage and are less than 1 mm in diameter. The absence of cartilage means that smooth muscle contraction reduces the size of the airway. Inflammation also results in reduction in size of the airway (Fig. 37.1).

Inhaled medicines used for asthma and COPD

Short-acting beta2 agonists

Salbutamol and terbutaline are short-acting beta2 agonists and are the most widely used inhaled bronchodilators. They act on beta2 receptors in the smooth muscle of bronchioles to reverse bronchospasm. The latter can cause symptoms including wheeze, coughing, breathlessness and a feeling of tightness of the chest. For this reason, short-acting beta2 agonists are often referred to as ‘relievers’ and should be used ‘as required’ to relieve symptoms. If a reliever inhaler is required for asthma more than three times a week most weeks, the addition of a ‘preventer’ (usually a steroid) inhaler should be considered.

Points to note

For COPD, a short-acting beta2 agonist may be prescribed for regular four times a day use as well as for symptom relief. In COPD, if a short-acting beta2 agonist is not sufficient, the next step may be to add a short-acting beta2 agonist/anticholinergic bronchodilator.

Unwanted effects of inhaled beta2 agonists are rare but tremor can occur.

Short-acting anticholinergics (antimuscarinics)

The most commonly prescribed short-acting anticholinergic bronchodilator is ipratropium. Smooth muscle relaxation is achieved by opposing the parasympathetic nervous system. Ipratropium requires four times daily inhalation, and is more commonly used in patients with COPD than in asthmatics.

Long-acting beta2 agonists

Salmeterol and formoterol are inhaled long-acting beta2 agonist bronchodilators. They are normally used twice daily, and are indicated for people with asthma who are symptomatic despite adequate doses of inhaled steroids. Formoterol is also licensed for once-daily use. These inhalers are sometimes referred to as ‘protectors’.

Long-acting anticholinergics

Tiotropium is a once-a-day inhaled anticholinergic indicated as regular preventative therapy for COPD.

Inhaled steroids

The powerful anti-inflammatory actions of steroids ideally suit them to control the inflammatory processes in asthma.

The inhaled route allows small doses of steroid to be used, minimizing the risk of systemic effects. The ideal inhaled steroid’s properties would include:

Using a spacer device with the steroid inhaler, and/or rinsing the mouth with water and spitting immediately after using the inhaled steroid may further reduce systemic effects.

Beclometasone, budesonide and fluticasone are examples of inhaled steroids. They are normally used twice daily. Budesonide is also licensed for once-daily use. Ciclesonide is a recently introduced inhaled steroid licensed for once-a-day use. Inhaled steroids are often referred to as ‘preventers’.

Inhaled steroids should normally be introduced:

The above measures form the basis for assessing control of asthma; in addition, limitation of exercise due to asthma and measures of lung function can be considered.

Points to note

Unwanted systemic effects of inhaled steroids are extremely rare provided that the total daily dose is less than the equivalent of 800–1000 micrograms beclometasone diproprionate.

Combination long-acting beta2 agonist/steroid inhalers

Salmeterol is combined with fluticasone in three different strength combinations as an aerosol metered dose inhaler (MDI) and in three different strength combinations as a dry powder inhaler (DPI). Formoterol and budesonide are combined in three different strength combinations as a dry powder inhaler. These inhalers are convenient for patients who require both an inhaled steroid and a long-acting beta2 agonist.

In general these combination inhalers are used as regular preventative therapy with the dose adjusted to achieve long-term control of asthma; a short-acting beta agonist inhaler being used for control of breakthrough symptoms. However, a budesonide 200 microgram/formoterol 6 microgram dry powder inhaler has recently been granted a license for preventer (maintenance) and reliever use for asthma. Thus some asthmatics who are using a budesonide 200 microgram/formoterol 6 microgram inhaler may only need to have one inhaler. A budesonide 200 microgram/formoterol 6 microgram inhaler can only be used for relief of symptoms if also being used as a regular preventer. It is not licensed for use before exercise to prevent exercise-induced asthma; an additional short-acting beta2 agonist should be used for this purpose.

Fluticasone 500 microgram/salmeterol 50 microgram dry powder inhaler and budesonide 400 microgram/formoterol 12 microgram dry powder inhaler, twice daily, are licensed for certain patients with COPD. That is for those whose forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) is less than 50% predicted and who are frequent exacerbators (two or more exacerbations per year).

The peak flow meter

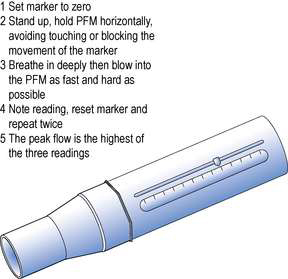

The peak flow meter (PFM) is a simple inexpensive device, prescribable on the NHS, which gives a useful objective measure of airways obstruction. A peak flow meter and its correct use is illustrated in Figure 37.2. The PFM measures peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR). PEFR is expressed in litres per minute (L/min). Flow rate of gas through a tube is proportional to the diameter of the tube when the pressure exerted on the gas is constant. Thus the maximum rate at which individuals can expel air from their lungs is proportional to the patency of the tubes in their lungs. A reduced PEFR indicates that there is obstruction to airflow in the lungs.

Asthmatics will obtain useful information about their condition by using the PFM twice daily and charting their results for 2–4 weeks in the following situations:

Normal values are available for PEFR in graph or chart form or on ‘wheels’. In adults, normal values for PEFR vary by age, sex and height; for children, PEFR varies just by height. Normal or average values of PEFR are just that and values of 50–100 L/min above or below a predicted value fall within the normal range. An increase of at least 20% in PEFR following the use of an inhaled short-acting beta2 agonist such as salbutamol is diagnostic of asthma. This is known as a reversibility test.

The PFM is of less value in COPD as the airways obstruction tends to be fixed rather than variable, and lung volumes may be more important. Spirometry, which measures FEV1 and forced vital capacity (FVC) is a more useful test of lung function in COPD.

Types of inhaler device

Aerosol inhalers

Metered dose inhaler (MDI)

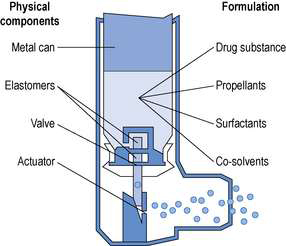

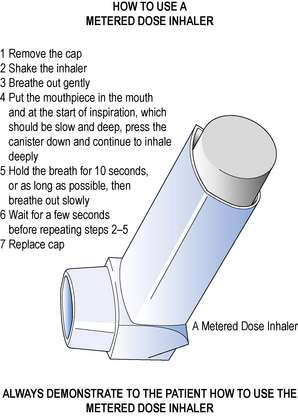

An MDI (Fig. 37.3) delivers an aerosol of drug dissolved or suspended in a propellant. Immediately an MDI is actuated, some of the propellant rapidly evaporates to produce droplets of appropriate size to be inhaled into the lung. Further evaporation of propellant may occur in the mouth and the so-called ‘cold-freon effect’ occurs if there is further evaporation of propellant (freon) when the aerosol impacts on the back of the throat. The sensation produced by the cold-freon effect can be sufficient in a minority of individuals to stop the inhalation and means that these individuals cannot use MDIs. The propellants currently used are generally hydrofluoro-alkanes (HFAs). Chlorofluoroalkanes, also known as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), were formerly used as propellants, but are now banned by international treaty because of their ozone-depleting properties. Medical aerosols were given exemption from the ban on CFCs, until alternatives were found and tested. Currently the change from CFCs to HFAs is not complete. It should perhaps be noted that while HFAs do not have the ozone-depleting effects of CFCs, both CFCs and HFAs are ‘greenhouse’ gases.

Patients who have previously had CFC-containing MDIs may be concerned when they start using a CFC-free MDI, because the taste and ‘feel’ of the aerosol is different. These differences are largely due to the fact that most CFC-containing MDIs are suspensions of drug in propellant, whereas most CFC-free MDIs are solutions of drug in propellant. Suspensions of drug in propellant result in nearly all the propellant evaporating after actuation and this can cause the cold-freon effect (see above). For many people this cooling sensation provides feedback that they are inhaling the drug. Solutions of drug in propellant result in only a fraction of the propellant evaporating after actuation, resulting in a reduced potential for the cold-freon effect but also a different ‘feel’ for the patient.

Surfactants such as oleic acid and cosolvents such as ethanol may be used to facilitate the production of an appropriate suspension or solution of drug in propellant.

The propellants, which are gases at room temperature, are maintained as liquids by filling under pressure into the metal aerosol canister.

A metered dose is achieved by having an appropriate size reservoir in the valve, which fills by gravity as the valve re-seats after each actuation.

The correct method of using an MDI is shown in Figure 37.4.

Common errors in using an MDI include:

Breath-actuated MDI

Inhaling through a breath-actuated MDI triggers a mechanism that ‘fires’ (actuates) the aerosol. These inhalers are particularly useful for those patients who have difficulty coordinating inspiration with actuation of the MDI.

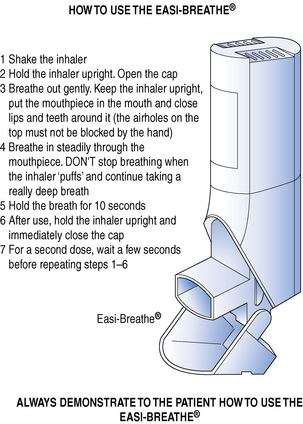

Easi-Breathe® is a type of breath-actuated MDI; its correct use is shown in Figure 37.5.

Autohaler® is another breath-actuated MDI. Using an Autohaler® is essentially the same as using an Easi-Breathe® except that the Autohaler® is primed by raising a lever on the top of the inhaler, whereas the Easi-Breathe® is primed by opening the mouthpiece cover.

MDI + spacer

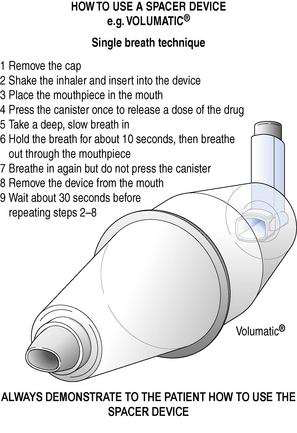

A chamber device (spacer) may be attached to an MDI (Fig. 37.6).

Fig. 37.6 How to use a spacer device, e.g. Volumatic®. Method for patients who can use the device without help. (Source: National Respiratory Training Centre.)

A spacer consists of a plastic chamber with a port at one end for the MDI and in most cases a one-way valve and mouthpiece at the other end.

An MDI + spacer is best used by firing a single dose from the MDI; inhalation should then start as soon as possible.

A spacer may be used with an MDI for the following reasons:

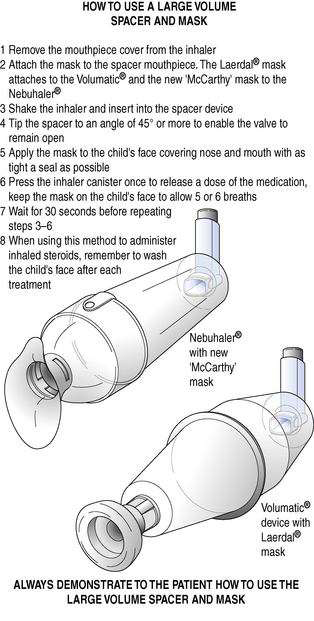

A mask may be attached or be integral to a spacer. The mask can then be placed over the mouth and nose of babies or infants to enable them to benefit from inhaled therapy. The correct use of a spacer and facemask is shown in Figure 37.7.

Fig. 37.7 How to use a large-volume spacer and face mask. (Source: National Respiratory Training Centre.)

Examples of spacers are Volumatic®, Nebuhaler® and Aerochamber®.

Dry powder inhaler (DPI)

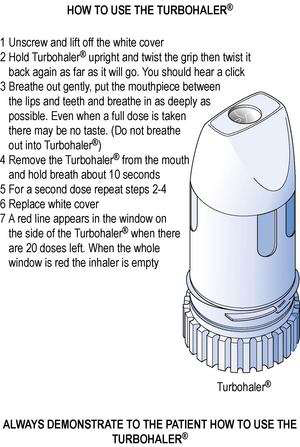

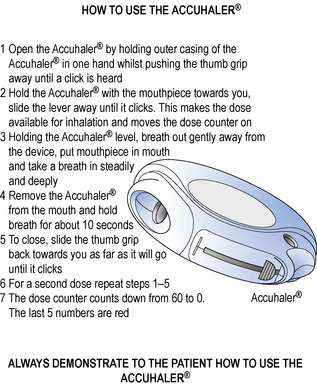

Medicines for inhalation can be presented as a micronized powder. The powder may be pure drug as in the Turbohaler®, or be drug and a carrier powder such as lactose, as in Rotacaps®, Diskhaler® and Accuhaler®.

When a carrier powder is used, the drug particles are adhered by weak electrostatic forces to the much larger carrier particles. As the drug/carrier powder is inhaled from the inhaler, the small respirable drug particles fly off the larger non-respirable carrier particles. The lactose carrier thus remains in the mouth. Patients using DPIs that employ a carrier powder should be reassured that even when using the inhaler correctly they will have carrier powder left in the mouth.

Patients inhaling pure drug from a Turbohaler® may experience little or no taste.

The correct method of using the Turbohaler® is shown in Figure 37.8 and the Accuhaler® in Figure 37.9.

All inhalers are boxed with instruction leaflets. However, the best way to learn how to use an inhaler is to have the technique demonstrated, then to attempt to use the inhaler under supervision so that any errors can be corrected. Many patients will benefit from pharmacists providing this service. Similarly, for pharmacists to best learn how to provide this service, they too should be shown how to use the inhaler and how to spot common errors. Medical representatives from companies that market inhalers are usually more than happy to train pharmacists how to use, demonstrate and check inhaler technique. As part of this service, the medical representative will provide placebo inhalers, to allow the pharmacist to demonstrate the correct inhaler technique, instruction leaflets and other patient education material.

The use and care of a DPI differs from that of an MDI, as shown in Table 37.1.

Table 37.1 Differences in the use and care of metered dose inhalers and dry powder inhalers

| MDI | DPI |

| Coordination of actuation and inhalation required | No coordination required as the release of powder and inhalation is a two-step process |

| Long, slow inhalation is the ideal to allow vaporization of propellants | Inhalation should be vigorous to disperse drug particles |

| Should be washed at least once a week to prevent blockage of actuator | Inhalers containing drug, e.g. Turbohaler®, must never be washed. Inhalers that do not contain drug, e.g. Rotahaler®, may be washed but must be completely dry before use |

| Exhalation prior to inhalation can be into the inhaler | Exhalation must never be into the inhaler |

Nebulizers

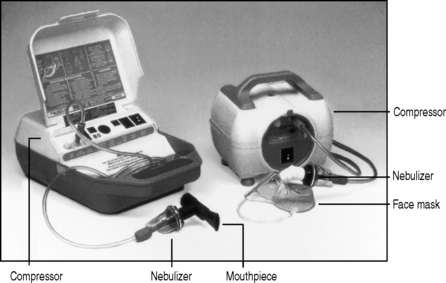

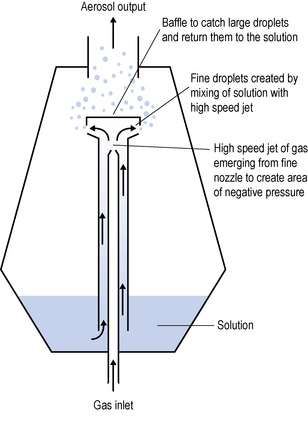

Medicines for inhalation can be presented as solutions or suspensions for nebulization. A nebulizing system (Fig. 37.10) usually consists of a compressor supplying compressed air to a nebulizing chamber, which delivers the nebulized drug to the patient via a mouthpiece or face mask. The face mask is most commonly used but when deposition of the nebulized drug on the face is undesirable (e.g. a steroid), then a mouthpiece is preferable, or the face under the mask should be protected with petroleum jelly.

The principle of jet nebulization is shown in Figure 37.11. The gas used to drive the nebulization process may be oxygen or air, but in either case a minimum flow rate of 8 L/min at a pressure of at least 69 kPa (10 psi) is required.

Patients using more than one nebulized medicine may have two different solutions mixed in the nebulizing chamber to be nebulized together. The Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) may give advice on other solutions and diluents that may be appropriately mixed with a given medicine for nebulization. It is possible that one solution will precipitate the other; this can normally be detected by the mixed solutions in the nebulizer changing from clear to cloudy. Such a change means that the mixed solutions are not compatible and should not be nebulized together. Consideration should also be given to the total volume of the mixed solutions, as the larger the volume, the longer it will take to be nebulized.

Nebulizers are used when high doses of drug are required and/or when the patient is unable to use any form of inhaler. Nebulizers do not require the patient to learn any technique and are effective on normal or shallow breathing.

Nebulizers are used in the treatment of severe acute asthma and this is best done under medical supervision:

Nebulized treatment may also be used in the latter stages of COPD often in conjunction with domiciliary oxygen therapy. Domiciliary oxygen cylinders do not provide sufficient flow rates to produce adequate nebulization, so a compressor unit should be used.

Drugs for nebulization are normally presented as unit dose vials; examples of these are Nebules® and Respules®.