Chapter 43 Storage of medicines and waste disposal

Introduction

Medicines, however well formulated, do not keep indefinitely. Some can only be kept for a short time before they have degraded sufficiently to make them unsafe or unsuitable for the patient. Such products are usually referred to as having a short shelf life. Other medicines last longer, sometimes up to several years, but always have a limited, although longer, shelf life. Rhodes (1984) listed six general causes for the degradation of medicines, and hence limited shelf life. These are:

To this list may be added changes which arise from microbiological activity.

All the above causes for the degradation of medicines can be speeded up by poor storage conditions. For example, extremes of temperature, exposure to bright sunlight, moisture, unsuitable packaging and even unsuitable transportation conditions can contribute to degradation and hence shortened shelf lives of medicines. Thus it is important to store medicinal products in the correct conditions at all times. Products that need to be kept cold or in a fridge require to be transported in refrigerated conditions, or if that is not possible, then in insulated containers. Such a transport system is referred to as a cold chain.

Poorly stored medicines may pose a safety hazard to patients – for example, if an incorrect or unavailable amount of drug is provided by a degraded formulation or if a formulation contains toxic degradation products. More information on the degradation of medicines can be found in Pharmaceutics: The Science of Dosage Form Design (Aulton 2007).

Pharmacists need to be aware of the potential for the degradation of medicines and the need to store medicines correctly in the pharmacy as well as advising patients about the correct storage of medicines in the home.

Expiry date

The expiry date is the date after which the medicine should not be used. This date is usually determined by accelerated stability testing (see Aulton 2007). The pharmaceutical manufacturer adds the expiry date to the package. In the case of extemporaneously prepared products, the shelf life, and hence the determination of the expiry date, may be found in an appropriate monograph (the British Pharmacopoeia or European Pharmacopoeia for example), if available. If there is not a monograph for the extemporaneous product, then the pharmacist should label the product with as short an expiry date as possible, bearing in mind the nature of the product. The safety of the patient should remain paramount.

Packaging

Most manufactured medicines will be supplied in purpose designed, elegant containers that will preserve the medicinal product for as long as possible. These containers may specify certain storage conditions, for example store between 2°C and 8°C in a refrigerator, or store in a dry place. Clearly a pharmacist must maintain the packaged medicine at such recommended storage conditions while it is under their control in the pharmacy, and advise the patient on storage conditions when the product is dispensed.

Stock control in the pharmacy

For reasons of economy as well as stability, pharmacists should not keep stocks of medicines on their shelves for long periods of time. The aim is to keep stock at a level which just meets demand. Nowadays, computerized systems of stock control are used in most community and hospital pharmacies. These computerized systems will monitor stock levels and record usage, and in addition, are capable of ordering or suggesting quantities to be ordered, based on past records, or ordering stock as it is used. Uncommon medicines or infrequently used medicines may have to be inputted into the computer system by pharmacy staff. But most everyday ordering decisions are not made by the pharmacist and the pharmacist can concentrate on the stock supply chain. However, the pharmacist should always keep an eye on stock levels and be aware of changes in prescribing, which will directly influence demand. After all, computer systems are only as good as the programming and the information inputted into the computer.

The stock supply chain

The procurement of stock is vital to the well-being of any business, including community and hospital pharmacy or any other supplier of services. The fundamentals apply whether it is a one man pharmacy, small pharmacy, large multiple pharmacy, hospital dispensary/manufacturing facility or even a robotic supply operation. The stock supply chain can be summed up in four main parts:

While each section will be looked at in some detail, the whole aim of the process is ‘The right product, in the right place, at the right time’. If this aim is followed alongside a robust standard operating procedure (SOP; see Chs 8, 9, 15) then any pharmacy should run in a way that avoids products being out of stock, short dated (near its expiry date) or out of date and, most importantly, the pharmacy should have the right amount of stock that can be afforded.

Procurement

The majority of pharmacies obtain most of their medicines and related products from one or two main wholesalers. These wholesalers are logistics experts and they make their profit by focusing all their efforts on supplying the right amount of product at the right time in the right place in a state that is ready for supply. A ‘good’ wholesaler makes life easier, not harder, for the pharmacy and generally will provide the following:

All the main wholesalers do all the above to a greater or lesser extent. The main difference between a well run and a poorly run dispensary is generally the staff training and utilization of systems and not the systems themselves. All the main computer systems will run stock and ordering systems but are dependent on correct information being provided. There must be clear disciplines in place that ensure that the dispensary IT system is up to date at all times. When these disciplines are applied rigidly and in a concise way, the computer system will work to its optimum and time and energy will be saved.

Receipt of goods

It is important that all pharmacy staff including the sales assistant, dispenser, accredited checking technician (ACT), pre-registration student and pharmacist have the same high regard for stock receipt and reconciliation. This is the lifeblood of a business and any amount of IT will not replace staff that are trained to correctly receive goods on delivery and to reconcile the stock. Reconciliation is the process of checking that the stock received is equal to the amount on the invoice or goods delivered documentation. Any pharmacy that does not have a robust checking procedure for the reconciliation of stock will be prone to abuse of that stock, including theft by customers and staff. This will lead to all sorts of potential leakage (loss of stock, usually by theft) and eventually loss of profit and in extreme cases loss of the business. It is absolutely vital that all staff involved in the procurement process are aware of the need for vigilance and security, and one way of doing this is to ensure a member of staff has ‘ownership’ of this process. There must be a clear and robust SOP for the receipt and reconciliation of stock and this must not be varied. If it is, then a gap in the process will be spotted and leakage will occur. The following is a brief synopsis of the receipt of goods, and although every pharmacy will be slightly different, the core values will be the same:

Storage

Once the right goods have been received and reconciled, then it is equally important that they are stored in a way that maximizes their shelf life. All modern medicines are formulated to enhance their stability; however, the general rules of storage are:

Rotation and date checking

Clinical governance (see Ch. 8) within pharmacy requires that date checking procedures be in place for all pharmacy stock, whether it is in the dispensary, stock room or shop (also see information on the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (RPSGB) website). One of the reasons is to protect the public from date expired medicines. Date expired medicines are likely to be substandard (degraded either chemically, physically or microbiologically) and may pose a safety issue if supplied to the public. Additionally it is professionally unacceptable and potentially illegal.

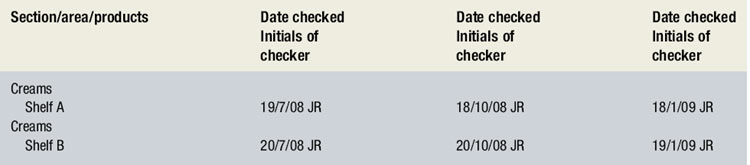

A SOP should cover rotation and date checking in the pharmacy. Ideally the overall responsibility for these tasks should be delegated to a senior member of staff, with individual staff responsible for certain areas or types of stock. All date checking should be recorded (see Ch. 15). Box 43.1 shows an example of a date checking record.

The general rules for date checking are as follows:

It may be possible to incorporate a quantity check at the same time as performing the date check. The benefit of a quantity check is that the position of the IT system can be checked and updated. Every system will corrupt with time and will require a person to update the system with the quantity on the shelf. Ideally a different 100 products a week should be checked and amended where required.

Storage in fridges

Many medicines require storage in a fridge to maintain the stability of the product for a reasonable time period (see examples in Box 43.2). The temperature of the fridge must be kept between the range of +2°C and +8°C. This temperature range should be maintained at all times and, ideally, an emergency power supply should be available in case of a power cut. The emergency power supply should provide power for a minimum of 24 hours.

The fridge cabinet should be sufficiently large to ensure that products are not tightly packed together so that cold air can circulate easily around the products. Airflow should not be obstructed in any way in the fridge.

As a fridge for storing medicines, it should not be used to store food and drink. Storage of food and drink could result in contamination of medicines.

All fridges for the storage of medicines must be fitted with a maximum–minimum thermometer, either mercury or digital, to enable temperatures to be recorded.

Fridge temperature monitoring

Fridge temperature monitoring is essential to ensure the public receives cold chain supplies of medicines in suitable condition. It is a professional requirement of the RPSGB that daily maximum and minimum temperatures within the fridge are recorded. This ensures correct storage conditions can be demonstrated for clinical governance (see Ch. 8).

Additionally, the fridge should be defrosted at regular intervals to maintain its efficiency. A record should be made of the dates of defrosting, again for clinical governance purposes. Alternative fridge facilities should be found for stock during defrosting procedures.

The following points are important for fridge temperature monitoring processes:

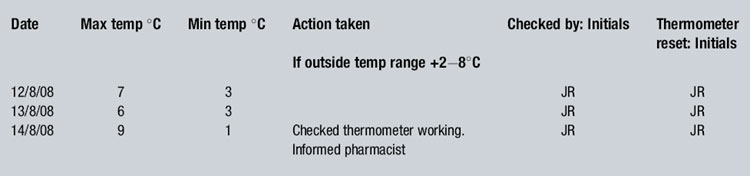

Box 43.3 shows a typical fridge temperature monitoring chart completed for 3 days, one of which shows an out of temperature range entry.

Waste

As a part of the new pharmacy contract in the UK it was agreed, as part of the essential services provided by all community pharmacies, that patients could return unwanted medicines. This on the face of it was a simple enough agreement and appeared to simply formalize a service that had been provided for years. Unfortunately, owing to a change in the environmental laws in the UK at about the same time, things were not quite as straightforward as planned.

It is vital for the health and safety of us all that medicines are not just dumped into household waste and/or flushed away down the toilet. The pollution of the rivers and lakes is so bad in some areas of the world that fish are changing their sex under the influence of hormonal contraception tablets which have been either disposed of by the patient or have leaked from landfill. The dumping of medicines into landfill is clearly unacceptable in view of the long-term consequences.

As a first step, every pharmacy that handles waste medicine must inform the local environmental health officer (EHO) in writing, or using the appropriate form, that they intend to store such waste. The exemption for storage is part of the Waste Management Licensing Regulations 1984. The EHO has agreed to allow pharmacies to store waste prior to collection and disposal by an authorized waste carrier. Generally the local primary care trust (PCT) in England will have a contract to collect waste on a regular basis by a third party who is licensed to transport and destroy waste. (NB: A pharmacy must have special registration to transport waste, see later.)

In order to be compliant with the law, it is vital that every pharmacy writes a standard operating procedure for handling of waste and ensures that there are appropriate facilities and tools to do the job properly. As a minimum, this means a dedicated area for storage on the premises, a clear list of questions for the patient returning medicines (see later), a definition of what pharmaceutical waste means (Box 43.4), a special disposal unit for controlled drugs, a clear method for dealing with spills, and a transparent record of what has happened to the waste, that is, a waste transfer note. The authorized waste carrier will always leave a waste transfer note when the waste is collected, and these notes must be stored in a place where they can be checked easily. Also it is important that the pharmacy contractor is clear where the waste is going and what is happening to that waste. It is not enough to hand waste to anyone who asks and then ignore what happens to it.

Box 43.4 Some definitions of waste from Hazardous Waste Regulations 2005

Hazardous Waste (England and Wales) Regulations 2005

Community pharmacists may only collect waste that is classified as household waste.

Removal of individual tablets or capsules from blister packaging falls within the definition of waste treatment (which is a licensed activity) and should be avoided by pharmacists

Another aspect which must be considered is health and safety at work. An employer and employees have a responsibility to work in a way that minimizes risk. Thus the first thing to do when receiving any waste from a patient is to tactfully ask the following questions and act according to the answers:

If the answer to either a) or b) is NO or the answer to c) is YES then you must reassess the situation, taking care that health and safety regulations are not compromised. For example, if a blood spattered bag containing open needles is offered, then it will be necessary to refuse to accept the bag and contents. Each occasion must be treated on its merits. The majority of patients are considerate individuals.

Generally the law allows sorting of the waste into solids (capsules and tablets), liquids and inhalers. Controlled drugs and hazardous waste should be kept separate and dealt with appropriately. There is a limit imposed on the amount of hazardous waste that may be handled in a year of 200 kg. It is very rare for a pharmacy to exceed this amount but if they do then a separate registration is required. Similarly, any pharmacy that, for business reasons, wished to transport waste, e.g. from a patient’s home, must be registered for this and pay a fee. It is not acceptable to pick up medicines from a patient’s house and transfer them in a vehicle without the proper registration and documentation. Fines can be hefty.

So as pharmacies have to take part in this valuable waste disposal service, the starting point is registration followed by writing a robust standard operating procedure which must be the basis of staff training. Any medicines must be stored securely on the registered premises of the pharmacy. An outside shed with no lock is not considered secure and will attract fines and a possible custodial sentence. Controlled drugs and hazardous waste must be treated separately and all spillages must be dealt with promptly and safely.

So is waste a waste of time? Categorically no; if a proper waste medicines management system is in place then there is less likelihood of:

These factors alone mean that waste management of medicines is quite correctly an ‘essential service’ for community pharmacy.