Chapter 47 Monitoring the patient

Introduction

Monitoring the patient may conjure up visions of healthcare professionals, including pharmacists, taking samples of blood and other body fluids from the patient, recording measurements, or merely observing them in order to manage a medical condition. While these are important examples of how monitoring may be achieved, there are other schemes that are used specifically in relation to monitoring patients and their medication.

Pharmacovigilance is the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse effects or any other drug-related problem. This has become increasingly important in evaluating medicines and providing checks, controls and warnings to healthcare professionals and patients.

The Yellow Card scheme

The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) is the government agency which is responsible for assessing the safety, quality and efficacy of a wide range of materials from medicines and medical devices to blood and therapeutic products that are derived from tissue engineering. The MHRA authorizes and regulates their sale or supply for human use in the UK.

Medicines are controlled as soon as they are first discovered and undergo clinical trials, but it is recognized that only the most common adverse drug reactions (ADRs) will be detected by the time the drug is marketed.

As part of its activities, the MHRA operates post-marketing surveillance and other systems for reporting, investigating and monitoring adverse reactions to medicines and adverse incidents involving medical devices. Included in this remit, the MHRA and the Commission on Human Medicines (CHM) run the UK’s national reporting system for ADRs – called the Yellow Card scheme (YCS).

The YCS was introduced in 1964 initially to provide doctors or dentists with a route to report a suspicion that a medicine could have harmed a patient. The YCS gets its name from the colour of the original document used for reporting the ADR. These ‘cards’ have become increasingly more accessible and can be sourced by a variety of methods (Box 47.1).

Box 47.1 Ways in which the Yellow Card reporting forms can be accessed

| Download | pdf copy (http://www.mhra.gov.uk) |

| Write to | MHRA, CHM Freepost, London, SW8 5BR |

| or CHM’s Yellow Card centres | |

| Copies included in | the British National Formulary (BNF), |

| the ABPI Medicines Compendium | |

| the MIMS Companion |

The fundamental principles of the scheme have not changed. Proof of a causal link between a medicine or a combination of medicines does not need to be established, so the reports are suspected ADRs.

In the UK, the MHRA collates data on ADRs via the YCS from a wide range of healthcare professionals working in the NHS or from private healthcare providers. These now include doctors, dentists, pharmacists (from 1997), nurses, midwives and health visitors (from 2002) and also HM Coroners. Reports are received directly from them and via pharmaceutical companies. The scheme is voluntary for healthcare professionals but pharmaceutical companies holding marketing authorizations have legal obligations to report ADRs to the MHRA.

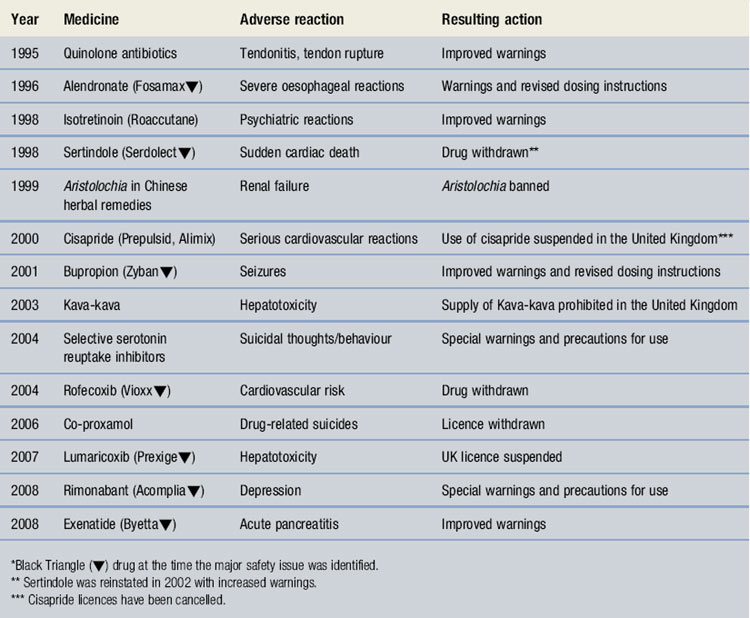

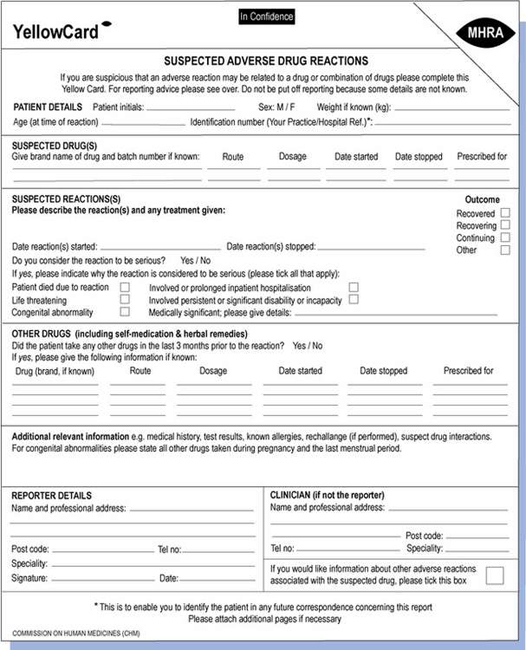

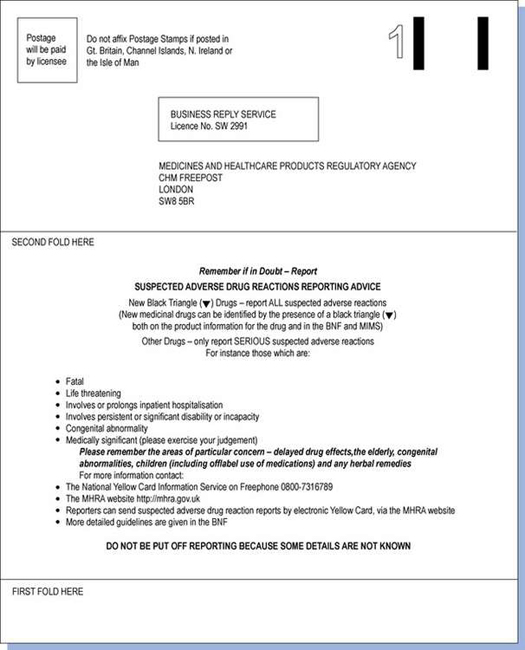

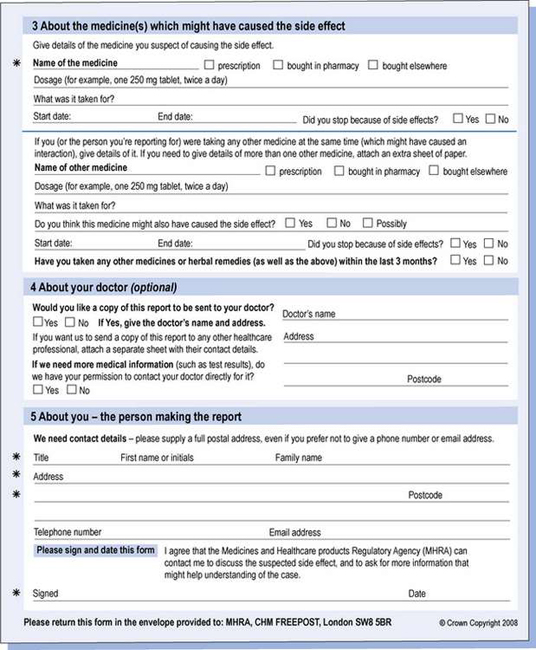

In January 2005 a 6 month limited pilot exercise was launched to include direct reporting by patients, followed by a nationwide pilot scheme in October 2006. This has continued with reports being accepted from patients, parents and carers. The Yellow Card report forms for patients are different from those for healthcare professionals. Standard report forms are shown in Figures 47.1 and 47.2.

Fig. 47.1 Standard Yellow Card report form for reporting suspected adverse drug reactions by healthcare professionals.

Fig. 47.2 Standard Yellow Card report form for reporting suspected adverse drug reactions by patients, parents and carers.

There have been over 500 000 reports received in the last 40 years. Yellow Card reports are collected on all types of medicines irrespective of legal status. These include:

The Commission and the MHRA continue to monitor intensively products carrying a black triangle symbol ( ) in the BNF. This identifies newly licensed medicines where the drug is a new active substance.

) in the BNF. This identifies newly licensed medicines where the drug is a new active substance.

However, additional criteria have also been applied when products have been selected for intensive monitoring, and include:

Healthcare professionals are asked to report all suspected ADRs for these products as opposed to focusing only on serious reactions for established products.

It has been suggested that the capacity of the scheme to identify ADRs should be strengthened by including other categories such as:

A product may retain black triangle status until the safety of the drug or product is well established, which is usually following 2 years of post-marketing experience. Over the last few years there have been 250–300 drugs under intensive surveillance (Black Triangle List) each year. A number are removed but are replaced by approximately the same number of new products each year. The list is regularly updated by the MHRA.

There are a number of problems associated with the scheme but the major one has been, and continues to be, under-reporting. Since October 2002 an Internet electronic Yellow Card has been available (http://www.mhra.gov.uk) to enable all reporters to submit ADR reports via the MHRA website in a paperless way.

Healthcare professionals are now encouraged to register with the site and use this method as it avoids reports being delayed or forgotten, as occurred when they had to be posted. In 2005 there was a 70% increase in the number of Internet reports received compared with the same period in the previous year. The online reporting form has been redesigned to improve clarity and usability by incorporating ‘drop-down’ menus and dictionaries for technical terms. A recently added feature allows a reporter to save a partially completed report at any point so that it can be finished and submitted at a convenient time or later when more information had been received concerning the ADR. This method may be the best way to encourage spontaneous reporting and it is being strongly promoted to all reporters. The MHRA and CHM also have five Yellow Card centres whose role focuses on follow-up of reports in their areas as this has been shown to improve follow-up rates.

Table 47.1 lists the number of Yellow Card reports received from healthcare professionals and patients in the period 1 November 2001 to 31 December 2006. Reporting of ADRs increased by approximately 5% each year compared to the same period of the previous year, but between January and May 2007 there was a 4% decrease compared with the same period in 2006.

Table 47.1 Reports of suspected adverse reactions (*comparing 1 November to 31 December of the next sequential year)

| Year* | No. of registered reports during period |

| 2001/02 | 20 481 |

| 2002/03 | 22 091 |

| 2003/04 | 23 158 |

| 2004/05 | 25 832 |

| 2005/06 | 27 075 |

Table 47.2 provides details on the specialty of the reporters for reports received during 1 November 2005 to 31 December 2006 with 2004/05 figures included for comparison. There has been a steady increase in the number of ADR reports from community pharmacists, other healthcare professionals and patients since the scheme was opened to them.

Table 47.2 Specialty of reporter for reports received between 1 November 2005 and 31 December 2006 (2004/05 figures for same period are given in brackets)

| Type of reporter | No. during period | Percentage of all reports |

| Community pharmacist | 689 (676) | 2.5 (2.6) |

| General practitioner | 4816 (6164) | 17.8 (23.9) |

| Hospital doctor | 5463 (6214) | 20.2 (24.0) |

| Hospital pharmacist | 3390 (3477) | 12.5 (13.5) |

| Nurse | 2327 (3098) | 8.6 (12.0) |

| Other healthcare professionals (including dentists, coroners, optometrists, psychiatrists, neurologists, paediatricians) | 6133 (5241) | 2.7 (20.3) |

| Patients | 4257 (962) | 15.7 (3.7) |

| Total | 27 075 (25 832) |

Patient reporting has been supported by the distribution of improved Yellow Cards to all GP surgeries, community pharmacies and other NHS outlets across the UK. The patient electronic Yellow Card has been updated and can also be accessed through the website.

Since the launch of the pilot scheme and up to August 2007, over 5500 suspected ADR reports have been received from patients. The patient report form uses a different format and less technical terms than those used by healthcare professionals. As a result, patient reports tend to provide more detail on the impact of the ADR on daily life and activities and initial observations indicate that the reports are of an equivalent level of seriousness to those of healthcare professionals. In September 2007 a 2-year research project was commissioned to formally evaluate the patient reporting component of the YCS and investigate the pharmacovigilance impact of these reports. The project is ongoing.

The Adverse Drug Reactions On-Line Information Tracking (ADROIT) system is the MHRA database used to store and monitor all the reports. Information collected through the scheme is an important means of monitoring drug safety in clinical practice and many important early warnings of new ADRs have been identified in addition to increasing the knowledge of known ADRs.

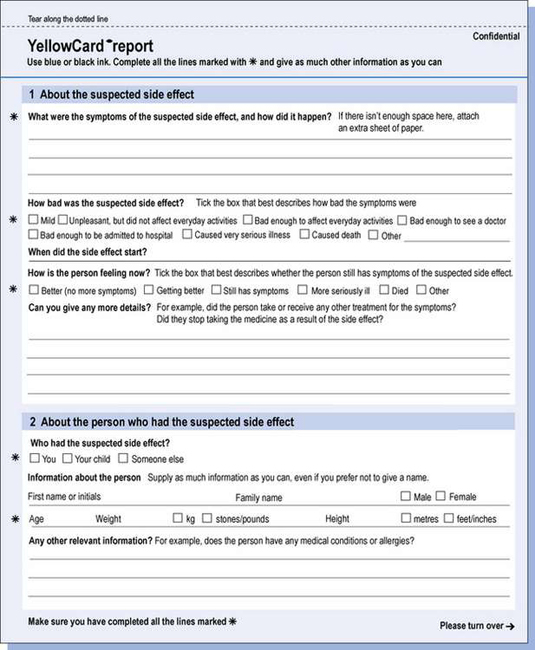

All data are closely scrutinized by the MHRA/CHM to determine whether a potential health threat is emerging and further investigation is required or more immediate action needs to be taken. The outcomes may be that the product licence for the drug is withdrawn by the regulatory authority when the risks are considered to outweigh the benefits. The company may voluntarily suspend or withdraw the product. In several instances, a drug has continued to be available following amendments to the summary of product characteristics (SPC) and patient information leaflet (PIL) indicating restrictions in use, reduction in dosages and special warnings and precautions. Some examples can be seen in Table 47.3. Complete listings of the suspected ADRs reported to the MHRA through the YCS by healthcare professionals and patients are provided in drug analysis prints. Drug analysis prints can be accessed from the MHRA website.

It is recognized that there are a number of problems with spontaneous reporting systems such as this. Under-reporting arises because healthcare professionals or patients do not recognize an ADR if it is unknown or difficult to spot. Conversely, there may be a bias to report ADRs that are well publicized. The true incidence of a particular ADR cannot be determined since there is a lack of information on the total number of patients exposed to the drug. The quality of the data reported is variable and some important details may be omitted and the report only indicates that an ADR is suspected, which does not imply causality, and false positives are mixed with true effects. The YCS is also poor at detecting long delayed reactions.

In addition, reporting systems in different countries differ and it becomes difficult to compare reports of ADRs across international boundaries. However, the World Health Organization’s regional monitoring centre in Uppsala is making progress in this area and is able to apply techniques to identify ‘signals’ of ADRs that require further investigations using reports from 78 countries.

Patient reports are not accepted by the majority of countries despite greater patient usage of complementary and alternative medicines which may increase the incidence of ADRs that are not reported by healthcare professionals.

The role of the pharmacist

Pharmacists have an important contribution to make in the prevention, identification, documentation and reporting of ADRs and in strengthening Yellow Card reporting. Currently the proportion of Yellow Cards received from pharmacists remains around 12%, whereas the proportion of patient reports submitted over a similar time period is 13%.

It is important that pharmacists are not reluctant to report suspected ADRs because they are often the healthcare professional most able to identify ADRs and to play an active role in their prevention.

On a daily basis the pharmacist becomes aware of factors that could indicate an ADR is occurring such as:

Their role as prescribers means they are more closely involved with the patient and the choice of medication. The expanding range of over the counter (OTC) medicines and the increasing number of medicines whose legal status has changed means that the responsibility of providing guidance to patients on the safe use of medicines frequently falls to the pharmacist. This also means that they should be advising patients to contribute to the YCS by completing forms themselves or encouraging patients to do so.

The future

For the future it is hoped that the information collected by the YCS can be used by researchers to help studies that will advance knowledge in the safe use of medicines. Examples of research applications that have been accepted include acute renal toxicity reported to the YCS and pharmacogenetics of antimicrobial drug-induced liver injury.

The medicines use review (MUR)/prescription intervention service

Background

The community pharmacy contractual framework (CPCF) for England and Wales was introduced in April 2005. The CPCF comprises ‘Essential’, ‘Advanced’ and ‘Enhanced’ service tiers. The medicines use review (MUR)/prescription intervention service is included under advanced services.

Although there are two service titles, in reality there is only one service, but the trigger which initiates provision is different.

The MUR is the first national service in which community pharmacists are remunerated to discuss the patient’s medication and support them in getting the most from their medicines. The pharmacist reviews the patient’s use, experience and taking of medicines together with identifying side-effects and interactions. They also aim to resolve any issues around poor or ineffective drug use by the patient and in this way carry out patient monitoring by a different process.

Following the first year of implementation, the national evaluation of the CPCF in 2007 indicated that 60% of pharmacies were providing the MUR service and over 80% of those who were not (mainly independents) planned to do so in the future. At the same time, this research suggested that GPs, primary care organizations (PCOs) and patients were unconvinced of the value of MURs. This was disappointing because the MUR was seen as the first opportunity for the pharmacist to demonstrate the added value that their input could make to patient care. In addition the commissioning of the next phase of ‘Enhanced’ services was thought to be dependent upon the demonstrated success of this service.

The reasons for the negative comments were linked to issues around the initiation of the service in the pharmacy and integration with general practice (Box 47.2). Since then the directions applying to MURs have been amended to incorporate a revised reporting form and GP (or equivalent) notification requirements. Uptake of the service has steadily increased, and the MUR is becoming more firmly established although it is still less than the suggested targets in some areas.

Box 47.2 Suggested barriers to initiation and integration of MUR service

Prescription interventions involve the same review, but are initiated in response to a significant problem with a person’s medication, rather than a periodic check. The same premises and pharmacist accreditation requirement apply.

Accreditation

A pharmacy can only provide advanced services if it is satisfactorily providing all the essential services in the CPCF. In order to provide MUR services, certain criteria must be met by both the pharmacy from which the service is taking place and the pharmacist who is providing the service.

Pharmacy criteria

As well as providing essential services, a pharmacy must have a consultation area:

If there is no space for a consultation room, pharmacists may conduct an MUR when the pharmacy is closed, making the whole pharmacy the consultation room. A request form has to be submitted to the PCO in order to do this.

Pharmacists’ criteria

Pharmacists must successfully undertake a competency assessment to gain accreditation before providing MURs.

Within the new contract negotiations, it was agreed with the Department of Health and the NHS Confederation that any higher education institution (HEI) should be able to provide training and competency assessments for the MUR service. A national competency framework is used as the basis for these assessments. The framework is not designed to be an exhaustive list of competencies that might be required to undertake MUR, but consists of those key elements that can be assessed in a robust and reliable manner.

There are a number of providers who run courses and/or competency assessments. Additionally some academic institutions that provide postgraduate clinical programmes, such as diplomas, have ensured their courses develop and test the skills of students in order to meet the requirements of the MUR competencies.

A list of providers across the UK is available from the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC) website.

A pharmacist registered with a primary care trust in England has to register separately in Wales – and a pharmacist registered with a local health board in Wales has to register separately in England.

A pharmacist must also apply to the PCO for permission to conduct MURs in special circumstances, for example at a patient’s own home, at a residential home, at an external clinic or on the phone. A separate request has to be made for each category of patient on each occasion.

Carrying out an MUR

Although it could be considered to be a simple task to carry out an MUR once the criteria for the premises and pharmacist have been satisfied, it still requires a considerable amount of planning and preparation to achieve a satisfactory result.

Patient selection

The first consideration concerns which patients are suitable, as selection must follow specified criteria. The national criteria for MUR other than prescription intervention indicate:

Local criteria

Most PCOs, working with their community pharmacies, may identify priority groups who would be appropriate for MURs, based on the needs of the local health economy. The most frequently reported groups being patients with respiratory disease (asthma and/or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) followed by those on multiple medications. Further examples of the range of patient groups that have been selected can be seen in Box 47.3.

Many pharmacists have or are looking to have areas of specialized interest and MURs provide them with an excellent opportunity to use this expertise in certain patient groups.

Pharmacists do not only select suitable patients themselves, they may accept referrals for MUR from the local surgery, other healthcare professionals, e.g. district and practice nurses, key workers and social services. In this way one of the perceived positive aspects for the CPCF, to allow the extended role of the community pharmacist to align with local health needs, may be achieved. The pharmacist can accept requests directly from patients for an MUR as long as the national criteria are met.

Prescription intervention

It should be noted that the patient selection criteria do not apply in the case of a ‘prescription intervention’, where the requirement for a MUR to be undertaken is initiated by the pharmacist identifying a significant problem during the dispensing of regular prescriptions. In particular, the requirement to have provided pharmaceutical services for a minimum of 3 months is removed. In these cases the initiating issue which led to the need for a prescription intervention is discussed with the patient as part of the MUR and communicated to the patient’s GP.

Engaging the patient

Since the service was introduced, engaging with patients to invite them to attend for the MUR has proved to be problematic. Patients must consent to an MUR being carried out. Initially uptake was poor because few patients had heard of the service and awareness of its purpose was low. Surveys had indicated that patients supported the concept of pharmacists helping them to understand what their medicines were for but patients were less inclined to attend an appointment to discuss their medicines. Many did not perceive that an annual MUR was required.

Similarly GPs and other relevant professionals had received little information about the service, availability was not guaranteed from all pharmacies and there were a number of other problems with the paperwork resulting in reluctance to signpost the service to patients.

Since that time steps have been taken locally and nationally to develop and provide support for those offering the MUR service. A leaflet for patients, explaining what the MUR entails, has been produced and is available from the Department of Health publications. An MUR information leaflet for GPs and practice managers is available from the PSNC (see Appendix 5).

Pharmacists have realized that they have to proactively engage patients to emphasize the benefits of the service and arrange appointments. To incorporate MURs into the daily work of the pharmacy without additional pharmacist cover is also difficult. Experience has now shown that the most successful MUR schemes use skill mix with pharmacy staff assisting with planning and preparatory work for the MUR. Pharmacy staff require an understanding of what MURs are about, but once this has been established they can work together to:

The patient interview

Despite pharmacists having extensive experience in communicating with patients, many have found the MUR interview difficult initially. Eliciting the information required to complete all sections of the form can be time-consuming if the patient is on multiple medications and sufficient preparation has not taken place. With experience, pharmacists have realized that the key areas they need to address are to:

This is in addition to all the general issues of putting the patient at ease, revising the purpose of the interview, active listening and appropriate responses to any comments or questions from the patient. They must also complete any sections on the form with the information they have received during or soon after the MUR.

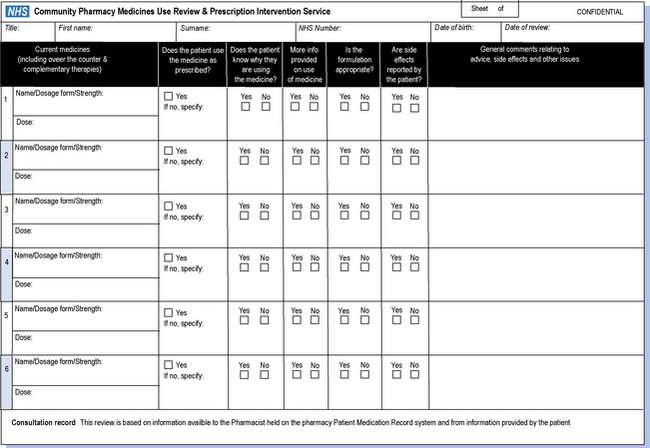

Completing the form

In December 2007, the new NHS MUR form (version 2) was published by the Department of Health as a result of feedback provided by stakeholders. Specific changes were made to the MUR form; it has been reduced down to two A4 sheets and the key details required by the patient’s GP/practice are all present on the first page – the Overview page (see Fig. 47.3). Sections have been moved to the front page and reworded in order to improve ease of use by GPs. The columns and rows for recording of drug name, dosage form, strength and dose have been revised and unnecessary annotation has been avoided by incorporating ‘tick’ boxes. Clinical codes for MUR have been added to facilitate recording of the MUR on GP systems (information provided by NHS Connecting for Health). An electronic template is now also available.

Fig. 47.3 NHS form for community pharmacy medicines use review and prescription intervention service.

In addition, guidance has been provided to give new flexibilities to pharmacists in the way the form is used. The patient must always be provided with a copy of the full MUR form, but pharmacists are now required to send the Overview page of the form to the patient’s GP within 7 days of conducting the MUR only when there are items that need to be considered by the GP/practice.

If there are no items to consider, the pharmacist needs only to notify the patient’s GP that an MUR has been undertaken within a month of the MUR being conducted.

These changes have made the system more efficient and acceptable to all those involved.

Interactions with GPs

The MUR is the first community pharmacy service where there is a formal requirement for communication between the pharmacist and the GP.

GPs have been slow to accept MURs because of the reasons stated previously. GPs have no authority to prevent pharmacists conducting them for their patients. In order to encourage the roll-out of MURs, pharmacists have produced newsletters and other forms of publicity and written to GPs to ask for practice visits to meet with and explain to them and their staff how the system can be beneficial to the patient. It has been emphasized that there can be significant health gain if MURs are delivered well. Those practices that have engaged with pharmacists and MURs have generally become enthusiastic supporters.

The future

The potential outcomes from MURs include improved attainment of health goals and quality of life through better use of medicines, reduced wastage and more effective use of resources. It is possible that patients will make fewer visits to the surgery and have reduced unplanned hospital admissions. To some extent these outcomes have been accepted, although a major flaw has been the lack of measurements and monitoring of the quality of the service. In the White Paper on Pharmacy, the government proposed that both of these should be addressed so that the longer term impact of MURs on improved compliance with prescribed medicines can be assessed.

MURs are one of the biggest innovations in community pharmacy in the last few years. They require community pharmacists to undertake functions complementing the work of GPs and other healthcare workers and align them to local health priorities. Improvement in patient knowledge ensures better medicines safety, a more rational approach to the use of medication and better monitoring.

MUR statistics collated for England since April 2005 are available to view on the PSNC website (see Appendix 5).