56 Lupoid onychodystrophy

INTRODUCTION

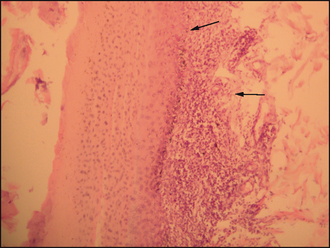

Lupoid onychitis, also known as symmetrical lupoid onychodystrophy, is considered to be an immune-mediated cutaneous reaction pattern. Often, the initial cause leads to secondary paronychia, which further contribute to the ongoing problem. The condition normally affects several claws on the feet, rather than just a single claw or a single foot and is characterized by progressive shedding of nails over a period of weeks to months with associated pain and paronychia. Histologically, it is characterized by a cell-rich interface dermatitis. Claw abnormalities are described using special terms and those used in this chapter are defined in Table 56.1.

Table 56.1 Various terms used to describe claw abnormalities in this case report

| Term | Visible abnormality of the claw |

|---|---|

| Onychitis | Inflammation of the claw |

| Onychodystrophy | Malformation of the claw |

| Onycholysis | Separation of claw from the claw bed |

| Onychomadesis | Sloughing of the claw |

| Paronychia | Inflammation of the claw bed |

| Onychalgia | Claw pain |

CASE HISTORY

Most dogs with lupoid onychitis are presented with a history of lameness, feet licking or pain. The duration of onset varies but commonly there is a history of sloughing of one nail and then over a period of weeks nails are sloughed on the majority, if not all, digits on all four feet. Haemorrhage may be evident from affected digits. Lupoid onychitis does not result in systemic illness and affected dogs are in good general health. The condition is not associated with poor nutrition and most dogs are being fed well-balanced commercial pet foods.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

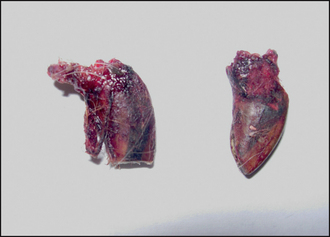

Onychomadesis and onychalgia are the most common presenting sign. The claws separate from the claw bed with evidence of exudate. Haemorrhage is not always seen, but when the nail plate comes away the claw may bleed profusely. Previously lost claws regrow in a dystrophic manner, with abnormalities such as brittleness, scaling, dryness and distortion.

Clinical findings in this case included:

The history and clinical signs were highly suggestive of lupoid onychitis. Some authors suggest that the combination of nail shedding affecting multiple digits with no evidence of systemic illness is pathognomonic for the disease. However, a number of different conditions were considered, including:

CASE WORK-UP

Based on the history and the clinical signs, trauma was ruled out because of multiple claw involvement. Several diagnostic tests are needed to rule in or out the many conditions that are responsible for claw disease.

The following tests were performed in this case:

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis is variable. Some cases respond reasonably well to benign therapy and nail care and have only rare recrudescence of disease. Other cases have repeated episodes of onychomadesis and are much more refractory to treatment. Lifelong treatment is likely to be required in these cases.

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY REFRESHER

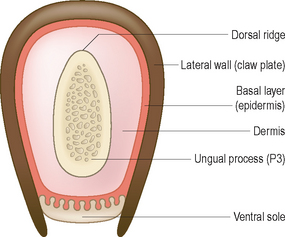

The claw is a specialized horny structure of the skin. It is formed of highly keratinized epidermis and, together with the underlying dermis, is a continuation of the skin covering the digits. The horny layer is formed from the basal layer of the epidermis overlying the dermis (the quick) that covers the distal phalanx.

The nail is supported by the third (distal) phalanx (Fig. 56.5). The distal phalanx is divided into a cone-shaped portion called the ungual process that is surrounded by a thin bony collar, the ungual crest. The claw fold is formed around the ungual crest. The coronary band, where most of the nail growth occurs, is the base of the claw abutting, and partially enclosed by, the ungual crest. Most of the claw’s growth is generated at the coronary band, and it is the differential growth rates between the coronary band, the dorsal and the ventral epidermis that produce the curved form of the claw. The claw itself is made up of three parts: the coronary band, the lateral and medial walls, and the ventral sole.

The lateral and medial walls are the main body of the nail. They are highly keratinized stratum corneum consisting of hard keratins, rich in cysteine, lipids and water, with little or no stratum granulosum. In cross-section, it is a hooped structure with free edges on its ventral aspect which are joined together by the ventral sole (Fig. 56.6).

The ventral sole is a softer structure that closes the base of the nail. It is stratum corneum but, unlike the walls, it also has distinct granular and clear layers.

The mineral composition of the canine claw includes calcium, magnesium, manganese, iron, potassium, sodium, copper, zinc and phosphorus. The roles of these minerals in maintaining claw condition are not understood, but differences have been noted between the normal and diseased states. However, the higher concentrations of calcium, phosphorus, potassium and sodium found in diseased claws suggest that mineral deficiency is not generally the cause of the disease.

Trauma is the most common cause of damage, when only a single claw is affected. If multiple claws on more than one foot are involved, then numerous aetiologies can be responsible for the clinical disease. They include:

In many cases, a specific disease may not be identified even after extensive investigations.

Lupoid onychitis, as in this case, is characterized by initial separation of the claw from the claw bed, followed by sloughing and eventually regrowth with variable claw abnormalities. Secondary bacterial infection is common. The disease can take several months to affect all the claws, and when the new claws grow back they are usually dry, brittle and often malformed.

The underlying mechanisms that lead to the immune reaction and nail damage are not clear in the majority of cases and are considered to be idiopathic. However, lupoid onychitis may be a manifestation of an adverse reaction to drug or food administration. Therefore, if there is no history of previous drug administration, a diet trial should be considered to rule out an adverse food reaction, although this was not done in this case.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

There is no age or sex predisposition to the condition, and whilst the condition is not breed specific, it appears to have a greater incidence in larger breeds, e.g. German shepherd dogs, giant schnauzers and Rottweilers. In the author’s experience the condition is also over-represented in bearded collies. A genetic predisposition may be inferred, as the condition has been reported in two siblings.

TREATMENT

This can be a challenging disease to treat and most dogs are likely to require long-term, possibly lifelong, therapy.

If presented in the acute stage of the disease, loose (and therefore painful) nails should be removed under heavy sedation or general anaesthesia. Cytology and perhaps culture and sensitivity testing should be performed on any exudate from nail folds and several weeks of antibacterial therapy should be prescribed based on the results of these tests. Appropriate dressings should be applied to the feet if required. Topical therapy in the form of antibacterial soaks in dilute chlorhexidine or similar antiseptic may also be beneficial.

Several anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive protocols have been reported for the treatment of lupoid onychitis. Less aggressive treatment regimens include high dosage omega-3/omega-6 fatty acid supplementation, vitamin E, biotin and the combination of oxytetracyline and nicotinamide. Biotin supplementation in cattle, pigs, horses and humans has been shown to improve the quality and the growth of hooves and nails respectively.

More severely affected dogs or those that are refractory to treatment may be treated with the immunosuppressive combination of prednisolone and azathioprine. Another protocol described the use of a topical betamethasone mousse combined with systemic treatment using pentoxifylline.

The choice of treatment is based on individual case assessment and discussion with the client. The potential adverse effects of more aggressive therapy with the requirement for haematological and biochemical monitoring and the associated cost, versus the potential benefit of the treatment, should be considered when making a choice for management.

Treatment in this case

In this case, cefalexin was prescribed at a dosage of 20 mg/kg b.i.d. and continued for a total of 6 weeks of treatment. At the same time, the dog was started on vitamine E (400 IU s.i.d.), biotin supplementation and a commercial essential fatty acid supplement using double the manufacturer’s dosage (i.e. 552 mg linoleic acid, 68 mg γ-linolenic acid, 34 mg eicosapentaenoic acid and 22 mg docasahexaenoic acid per 10 kg body weight). Although a combination of oxytetracyline/nocotinamide was considered, it was not prescribed at the first instance. After the initial 6 weeks of antibiotic treatment (Fig. 56.7), a combination of 500 mg of oxytetracycline and 500 mg of nicotinamide t.i.d were prescribed for 3 months.

Figure 56.7 The claws after 6 weeks of treatment with cefalexin, Efavet regular, vitamin E and biotin.

Advice was given to the owners regarding the necessity of careful nail care. Nails should be regularly clipped and if possible, split nails should be filed to remove sharp edges that could result in further nail fracture.

As many owners find nail clipping difficult, nurses should be involved in the nail care of lupoid onychitis cases. Regular clipping and filing of the claws, to reduce the pressure on the claw bed, can be of value in the long-term management of the disease.

FOLLOW-UP

The dog was maintained on the combination of essential fatty acid, vitamin E and biotin supplements long term. The oxytetracycline and nicotinamide combination was withdrawn after 3 months of treatment. The owners were diligent with long-term claw care for the dog; however, the claws continued to grow abnormally and the dog lost another claw after 9 months. A further 8-week course of oxytetracycline and nicotinamide (500 mg of each t.i.d.) was prescribed. Since then there has been no further nail loss.

Total T4 and thyroid-stimulating hormone have been within normal reference ranges when measured on two separate occasions 6 months apart. Thyroglobulin antibodies, however, remain elevated.

A food trial was not undertaken in this case, one reason being the only way the owner was able to administer the supplements was with special treats.