3 Emergency database interpretation

Together with an astute major body system examination, an immense amount of useful information can be derived from an emergency database. Traditionally the minimum emergency database consists of manual packed cell volume (PCV), plasma total solids (TS), blood glucose concentration and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) concentration. Where possible the author prefers to measure plasma creatinine concentration alongside BUN as creatinine is less prone to acute fluctuations. Gross plasma appearance may also provide valuable information.

In addition to the minimum emergency database, it is often appropriate to perform additional measurements or tests as part of the emergency database for specific patient populations. These include:

Depending on the facilities available, it may be possible to obtain all the blood required for the emergency database from an intravenous catheter at the time of placement.

Packed cell Volume and Plasma Total Solids

Manual PCV and TS should always be interpreted together and the changes identified will raise the index of suspicion for particular causes (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1 Interpretation of manual packed cell volume and plasma total solids

| Packed cell volume (%) | Plasma total solids (g/L) | Causes to consider |

|---|---|---|

| Decreased | Normal | |

| Decreased | Decreased | |

| Normal | Increased | |

| Normal | Decreased | |

| Increased | Normal | |

| Increased | Increased | Dehydration |

Reduction in PCV and TS following haemorrhage is the result of dilution by fluid moving into the bloodstream from the interstitium. However, this decrease does not occur immediately as there is a lag for fluid movement to occur. Furthermore, in dogs, but not cats, splenic contraction occurs following acute haemorrhage to increase circulating red blood cell mass. Therefore PCV may be normal in the face of low TS following acute haemorrhage and these findings must be interpreted in light of the patient’s history and physical examination findings.

With the exception of haemorrhage and protein-losing enteropathy (PLE), most causes of hypoproteinaemia relate to hypoalbuminaemia. Causes of hypoalbuminaemia include protein-losing nephropathy (PLN), liver failure, malnutrition/malabsorption, chronic effusions and exudative skin lesions. Hyperglobulinaemia may occur secondary to dehydration but also inflammation, monoclonal gammopathy (e.g. due to plasma cell myeloma) and polyclonal gammopathy (e.g. due to chronic inflammatory disease, inflammatory bowel disease, feline infectious peritonitis).

When interpreting changes in all laboratory parameters, including PCV and TS, it is important to remember that normal ranges cited for adult dogs and cats may not be applicable to puppies and kittens (see Ch. 41).

Gross Plasma Appearance

Common abnormalities of plasma appearance and possible causes are listed in Table 3.2. In addition to plasma appearance, samples can be evaluated for the size of the buffy coat following centrifugation, with a large buffy coat suggestive of leukocytosis.

Table 3.2 Possible causes of abnormalities in gross plasma appearance

| Plasma appearance | Possible causes |

|---|---|

| Haemolysed | |

| Icteric | |

| Lipaemic |

Blood Glucose Concentration

Clinically significant hyperglycaemia requiring specific therapy is typically only associated with patients suffering from diabetes mellitus. Hyperglycaemia not requiring treatment may also be seen in other endocrine disorders (hyperadrenocorticism and acromegaly), secondary to stress (especially cats) and following seizures and head trauma.

Clinically significant hypoglycaemia requiring treatment is seen most commonly as a result of hyperinsulinism, iatrogenic causes or neoplasia, and in very young animals or toy breed dogs. Hypoglycaemia may also be identified in hypoadrenocorticism, liver failure, sepsis and heatstroke.

Azotaemia

The causes of azotaemia may be divided into prerenal, renal or postrenal.

Prerenal azotaemia

Prerenal azotaemia occurs as a result of reduced renal perfusion and a consequent functional decrease in glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Causes include dehydration, hypovolaemia and heart failure. Prerenal azotaemia is characterized by increased PCV, TS and urine specific gravity (USG), and is usually only mild. It is typically reversible but structural renal injury and renal azotaemia may develop if renal hypoperfusion is protracted.

Renal azotaemia

Renal azotaemia occurs as a result of reduced GFR secondary to structural renal changes. Urine specific gravity is isosthenuric (1.007–1.015) as the kidneys are no longer able to concentrate or dilute the urine and azotaemia may be mild, moderate or severe. Anaemia may be present with chronic renal insufficiency.

Clinical Tip

Postrenal azotaemia

Postrenal azotaemia occurs due to urinary tract obstruction or rupture which prevents excretion of urea and creatinine from the body. Azotaemia in these cases may be very severe but frequently will fully resolve with appropriate correction of the underlying disorder. Protracted urinary outflow obstruction can result in damage to the renal parenchyma and consequent intrinsic acute renal failure.

Peripheral Blood Smear Examination

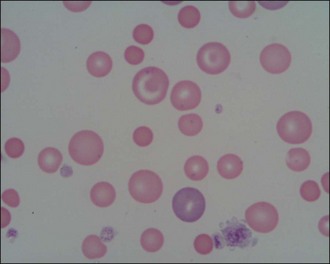

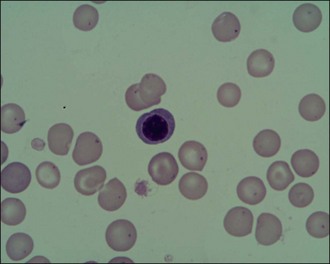

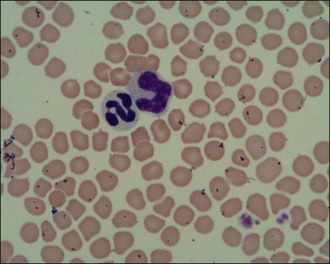

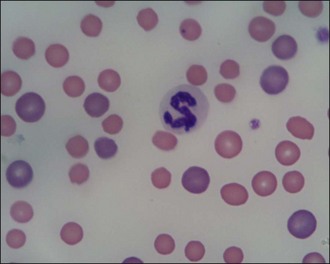

Peripheral blood smear examination is recommended for the majority of emergency patients. Cytology allows cell morphology to be evaluated and abnormal cell populations to be identified; a degree of quantitative information can also be obtained. Red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets are evaluated (Figures 3.1 and 3.2).

Figure 3.1 Normal canine red blood cells, neutrophil, monocyte and platelets (×1000)

(Photograph courtesy of Kate English).

Figure 3.2 Normal feline red blood cells, neutrophil, monocyte and platelets (×1000)

(Photograph courtesy of Kate English).

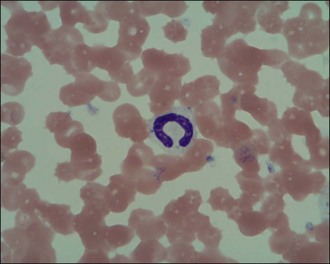

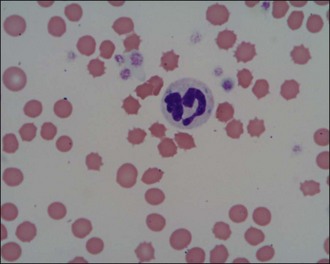

Red blood cells

Red blood cells are examined for variability in size (anisocytosis) and colour (polychromasia) (Figure 3.3), both of which are suggestive of regenerative anaemia. When stained using a Romanowsky stain such as Diff-Quik, immature red blood cells (polychromatophils), which are larger than mature cells, have a purplish- or bluish-tinged appearance.

Figure 3.3 Peripheral blood smear from a dog showing regenerative anaemia (×1000). Marked polychromasia (large purplish-tinged red blood cells) and anisocytosis (variation in red blood cell size) is present; a neutrophil and two platelets can also be seen.

(Photograph courtesy of Kate English)

Red blood cells should also be examined for additional features such as spherocytosis (Figure 3.4) and the presence of increased numbers of nucleated red cells (Figure 3.5). Spherocytes are smaller, more rounded and denser staining than normal red blood cells and they lack central pallor. They are formed when red blood cells undergo partial phagocytosis and are characteristic of immune-mediated haemolytic anaemia (see Ch. 33). Nucleated red cells may be seen for example with strongly regenerative anaemia or heatstroke (see Ch. 38).

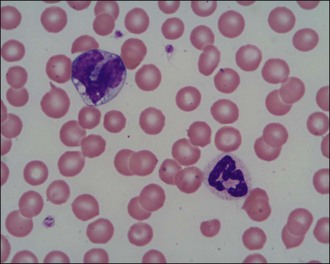

White blood cells

Neutrophils are the white blood cells of main concern in most cases and it is generally acceptable in the emergency setting to make a subjective assessment of neutrophilia or neutropenia in the context of the patient in question. The proportion of band neutrophils (Figure 3.6) should be estimated. These are immature neutrophils with unsegmented nuclei released early from the bone marrow in response to acute demand. A normal or low neutrophil count with a high proportion of band cells is referred to as a degenerate left shift and indicates severe pathology. Neutrophils should also be examined for toxic changes (Figure 3.7) which are morphological abnormalities that occur during intensified neutrophil maturation in severe inflammation.

Figure 3.7 Canine toxic neutrophil showing cytoplasmic basophilia, toxic granulation and three Döhle bodies (×1000).

(Photograph courtesy of Kate English)

Leukopenia may be the result of reduced production (e.g. parvovirus, immunosuppressive therapy) or sequestration (e.g. severe infection or inflammation).

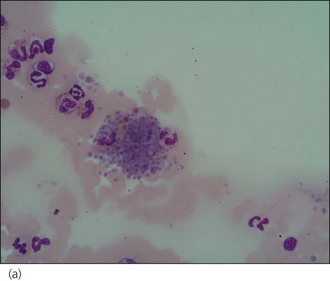

Platelets

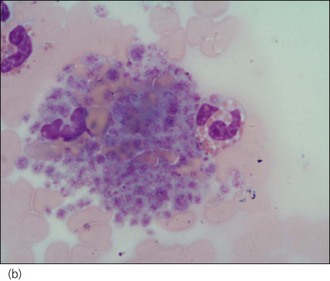

A manual platelet count should be performed under high power (×1000, under oil immersion) in the monolayer of the smear. Guidelines vary but 1 platelet per high power field may be considered equivalent to 15–20 × 109 platelets/litre. Prior to performing the count, the feathered edge should be examined for the presence of platelet clumps (Figure 3.8) which will reduce the number of platelets in the monolayer and if missed, may lead to a misdiagnosis of thrombocytopenia. Platelet clumping implies an adequate platelet count. Large platelets may be seen as part of a regenerative platelet response for example following haemorrhage. In addition, macrothrombocytopenia is recognized in Cavalier King Charles spaniels.

Figure 3.8 Canine platelet clump: (a) ×400 magnification; (b) ×1000 magnification.

(Photographs courtesy of Kate English)

Spontaneous haemorrhage secondary to thrombocytopenia is unlikely to be seen in patients with two or more platelets per high power field although it must be remembered that this is only a guideline. It can be difficult to identify even a single platelet in smears from animals with immune-mediated thrombocytopenia (see Ch. 33).

Plasma Electrolytes

Potassium

Hyperkalaemia

Some of the more common causes of hyperkalaemia are listed in Box 3.1.

BOX 3.1 Causes of hyperkalaemia

Release of intracellular potassium

Contamination of plasma sample with potassium EDTA during transfer into blood tubes

Hypokalaemia

Hypokalaemia in emergency patients is most commonly the result of reduced intake due to inappetence, and concurrent increased loss via the gastrointestinal tract due to vomiting and/or diarrhoea. Excessive loss may also occur via the urinary system, for example in some animals (especially cats) with chronic renal failure or secondary to loop or thiazide diuretic administration.

Sodium

Sodium metabolism and water balance are closely interconnected via complex mechanisms involving a number of different receptors and hormones, and it is therefore essential to consider the patient’s intravascular volume status when interpreting measured serum sodium concentration. Some causes of hyper- and hyponatraemia are listed in Tables 3.3 and 3.4.

Table 3.3 Causes of hypernatraemia

| Hypovolaemia (water loss is greater than sodium loss, i.e. hypotonic fluid loss) | |

| Normovolaemia (pure water deficit) | |

| Hypervolaemia (impermeant solute gain) |

Table 3.4 Causes of hyponatraemia

| Hypovolaemia (sodium loss is greater than water loss) | |

| Normovolaemia (pure water deficit) | |

| Hypervolaemia (water excretion reduced) |

Clinical Tip

Calcium

In the blood, calcium is found in three forms: ionized, protein-bound and complexed (e.g. with phosphate, bicarbonate). Ionized calcium is the most important biologically active form and accounts for 50–60% of total serum calcium in normal dogs. Measurement of total calcium is more widely available but may not reliably correlate with ionized calcium concentration.

Young dogs (typically less than 1 year old) may have serum calcium concentrations that are greater than quoted reference ranges for adult dogs. This is presumed to be due to normal bone growth and should not be overlooked when interpreting results from this patient population.

Hypercalcaemia

Hypercalcaemia may occur secondary to a number of disorders and may in turn have adverse pathophysiological effects, most notably on the kidneys, heart, central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract. A useful acronym for remembering the most common conditions associated with hypercalcaemia is HARDIONS and is explained further in Table 3.5. Transient mild hypercalcaemia has also been associated with haemoconcentration, hyperproteinaemia and severe hypothermia.

Table 3.5 Common conditions associated with hypercalcaemia

| Cause | Notes |

|---|---|

| H: primary Hyperparathyroidism | |

| A: hypoadrenocorticism (Addison’s disease) | Transient, clinically insignificant |

| R: Renal failure | Chronic or polyuric acute renal failure |

| D: hypervitaminosis D | |

| I: Idiopathic | Most common form in cats |

| O: Osteolysis | |

| N: Neoplasia | Humoral hypercalcaemia of malignancy most common cause in dogs; commonly due to lymphoma or anal sac apocrine gland adenocarcinoma |

| S: granulomatouS disease | e.g. panniculitis and angiostrongylosis |

Hypocalcaemia

A large number of conditions are associated with hypocalcaemia and the more common ones are listed in Box 3.2.

Urinalysis

Urinalysis is recommended in all emergency patients found to be azotaemic or where there are concerns for example regarding urinary tract infection. It is preferable to obtain urine for analysis prior to administration of intravenous fluid therapy or other drugs (e.g. diuretics, glucocorticoids) that may alter urine production. However, treatment that is urgently required should not be withheld purely for the purposes of obtaining a urine sample. Urine may be collected by voiding (midstream sample), catheterization or cystocentesis as appropriate. Voided samples are preferred for detection of haematuria due to risk of traumatic haemorrhage with the other techniques, and cystocentesis is arguably preferred for collection of samples for microbiology as it avoids possible urethral and/or genital contamination of the sample.

Gross discoloration

Gross appearance may be suggestive of certain disorders. Haematuria, haemoglobinuria and myoglobinuria are variably associated with urine that is pink, red, red-brown or brown in appearance. Methaemoglobinuria is also associated with brown urine. Significant bilirubinuria is associated with orangey urine while cloudy urine is typically the result of pyuria, crystalluria or mucus.

Specific gravity

USG is a measure of total solute concentration and reflects the ability of the kidneys to concentrate or dilute glomerular filtrate derived from plasma. Normal USG varies widely amongst dogs and cats. Isosthenuria is defined as USG of 1.007–1.015. This reflects the same total solute concentration as plasma and suggests inability of the kidneys to modify the initial filtrate. Isosthenuria is usually associated with renal azotaemia.

Clinical Tip

Concentrated urine (USG more than 1.015) and hyposthenuria (USG less than 1.007) suggest some renal tubular function. Increased USG is expected in animals with prerenal azotaemia.

Dipstick analysis

With respect to emergency patients, dipstick analysis is most likely to be useful for detection of glucosuria and ketonuria. Glucosuria is diagnostic for diabetes mellitus when accompanied by significant hyperglycaemia. However, glucosuria is occasionally detected without hyperglycaemia in conditions involving renal tubular dysfunction (e.g. seen with some nephrotoxins). Glucosuria and hyperglycaemia may also be seen in stressed or excited cats.

Ketones are produced as a result of incomplete fatty acid oxidation and ketonuria is most commonly due to diabetic ketoacidosis. Other less common causes of increased ketone production and ketonuria include starvation, prolonged fasting or persistent hypoglycaemia. Acetone, acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate are the three ketones produced and it is of note that the reagents in commercial urine dipsticks will not detect β-hydroxybutyrate.

Clinical Tip

Dipsticks are unable to differentiate haematuria, haemoglobinuria and myoglobinuria. Haematuria and haemoglobinuria can be differentiated by sediment examination. In contrast to animals with haemoglobinuria in which plasma is also likely to be discoloured secondary to haemoglobinaemia, plasma in animals with myoglobinuria is likely to be clear. Some causes of haematuria, haemoglobinuria and myoglobinuria are listed in Box 3.3.

Dipsticks should not be used to diagnose the presence of leukocytes in canine or feline urine as the methodology employed is unreliable in these species. Sediment examination is the diagnostic technique of choice. Mild to moderate bilirubinuria may be normal in dogs, especially males, but is always considered an abnormal finding in cats. Causes of bilirubinuria include haemolysis, hepatobiliary disorders, pyrexia and starvation.

Sediment examination

Urine sediment should be examined as quickly as possible after collection to minimize degeneration of casts and cells. Sediment may be examined unstained or can be stained with a commercial stain specifically intended for use with urine (e.g. Sedi-Stain™). The author, however, prefers to stain urine sediment with Diff-Quik. Sediment is examined for the number of red and white blood cells per high power field, infectious organisms (typically bacteria), crystals, and number of casts per low power field.

Especially in the presence of haematuria and proteinuria, more than five white blood cells per high power field are suggestive of inflammation (infectious or noninfectious in origin) in a sample obtained via catheterization. A lower cut-off may be more appropriate in a sample obtained via cystocentesis and a higher cut-off in a voided sample. Urine should be submitted for culture and sensitivity if bacteriuria or pyuria is identified.