33 Haematological and haemostatic emergencies

Canine Immune-Mediated Haemolytic Anaemia (IMHA)

Theory refresher

Immune-mediated haemolytic anaemia (IMHA) is the result of red blood cell destruction by the immune system. Red blood cell destruction is initiated by the binding of immunoglobulin G (IgG) or IgM antibodies and complement to their surface. Both extravascular (reticuloendothelial system) and intravascular (causes haemoglobinaemia, haemoglobinuria) haemolysis may occur.

IMHA is generally classified into primary (idiopathic) IMHA, in which no inciting cause is identified, and secondary IMHA, which is associated with an underlying condition (Box 33.1). Primary IMHA is typically diagnosed in young or middle-aged adult dogs but can occur in older dogs too. IMHA is especially common in certain breeds (e.g. English springer spaniel, American Cocker Spaniel). These dogs were previously classified as having primary IMHA although this classification may no longer be appropriate given their genetic predisposition. In dogs with secondary IMHA, the underlying condition may or may not persist at the time of presentation, and may or may not be amenable to specific therapy. In the absence of useful historical information (e.g. with respect to drug administration or vaccination), thorough physical examination, thoracic and abdominal diagnostic imaging, urine microbiology and additional investigations as appropriate are required to rule out an underlying trigger for IMHA.

BOX 33.1 Underlying conditions potentially associated with immune-mediated haemolytic anaemia

FeLV, feline leukaemia virus; FIV, feline immunodeficiency virus.

Hereditary erythrocyte enzyme defects should be kept in mind as possible differential diagnoses in dogs of affected breeds presenting with evidence of haemolytic anaemia. Phosphofructokinase (PFK) deficiency occurs especially in the English springer spaniel, Cocker Spaniel breeds, and mixed breed dogs. Pyruvate kinase (PK) deficiency is most commonly reported in the Basenji as well as in several other breeds including the Beagle, the West Highland White terrier, the Cairn terrier and the miniature poodle.

Treatment

Medical therapy to decrease erythrocyte phagocytosis, complement activation and anti-erythrocytic antibody production is essential for primary IMHA and glucocorticoids are the mainstay of acute therapy. Other immunosuppressive agents may be used in addition to, but not instead of, glucocorticoids (Box 33.2). Immunosuppressive therapy is typically also required for secondary IMHA although success is significantly dependent on whether the underlying condition persists and, if so, whether or not it is amenable to treatment. Clearly with neoplastic conditions in particular, it may not be possible or appropriate to treat the patient.

BOX 33.2 Immunosuppressive agents that may be considered in addition to glucocorticoids in canine immune-mediated haemolytic anaemia (IMHA)

Although there is limited evidence for their efficacy in IMHA, the author typically uses one of these agents in all dogs with primary IMHA in an attempt to allow prednisolone therapy to be tapered more quickly, thereby minimizing side effects. Azathioprine is the cheapest option and is therefore used where possible. However, it likely has the slowest onset of action with a lag of 7–14 days and is therefore started as early as possible. Mycophenolate mofetil and especially ciclosporin are more expensive but may have a quicker onset of action. They are therefore typically only used in cases in which response to glucocorticoids is inadequate. The author has no experience with the use of cyclophosphamide.

Dogs with IMHA are at increased risk of thromboembolic complications, especially pulmonary thromboembolism (causes dyspnoea, tachypnoea, cyanosis). Anticoagulant therapy is therefore used in addition to the immunosuppressive therapy. However, there remains much to be clarified with respect to both coagulation abnormalities in IMHA and the most effective preventative and therapeutic treatments. At the time of writing, ultralow dose (0.5 mg/kg p.o. q 24 hr) aspirin therapy is most widely recommended and discontinued at the same time as glucocorticoid administration ceases.

Case example 1

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 4-year-old female neutered English springer spaniel dog presented with a 2-day history of progressive lethargy, exercise intolerance and inappetence. The owner had noticed the dog passing grossly discoloured urine (pigmenturia), prompting emergency presentation. The dog had last received routine annual vaccination 6 months prior to presentation, and there was no recent history of drug administration. There was no notable history of travel and no other significant history was reported.

Major body system examination

On presentation the dog was ambulatory but weak and depressed. Cardiovascular examination revealed a heart rate of 136 beats per minute with no murmur or gallop sound heard. Peripheral pulses were hyperdynamic in quality without deficits, and mucous membranes were very pale with a rapid capillary refill time. Respiratory rate was 40 breaths per minute with a shallow pattern and lung auscultation was appropriate for the rate and effort. Abdominal palpation was unremarkable and the dog was mildly pyrexic (rectal temperature 39.3°C). Digital examination per rectum revealed normal faeces without evidence of melaena or fresh haemorrhage. Peripheral lymph nodes were normal, and no other abnormalities were detected; in particular, there was no evidence of jaundice.

Assessment

The tachycardia in this case may have been the result of mild hypovolaemia but mucous membranes were much paler than would be expected in such cases; mild hypovolaemia is associated with normal or pinker than normal mucous membranes. Very pale mucous membranes are associated with severe hypovolaemia but the dog’s heart rate, peripheral pulse quality and mentation were not consistent with this. It was therefore suspected that the pallor was predominantly related to anaemia. Peripheral pulses have a fairly characteristic quality in anaemia and were consistent with anaemia in this case. The dog was therefore suspected to be showing signs of cardiorespiratory compensation for severe anaemia and, given her breed, there was a high index of suspicion for primary (idiopathic) IMHA. Mild pyrexia is a relatively common finding in such cases.

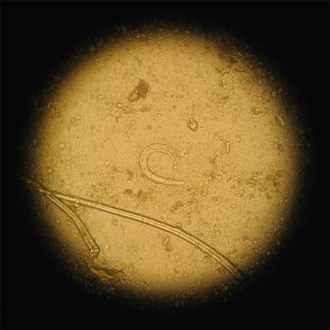

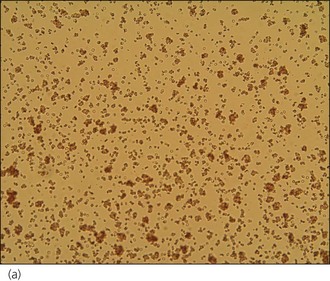

Emergency database

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and blood obtained via the catheter for an emergency database to be performed. This revealed severe anaemia (manual packed cell volume (PCV) 14%, reference range 37–55%) with raised plasma total solids (78 g/l, reference range 49–71 g/l); however, the serum was icteric in appearance. These findings were consistent with the suspicion of haemolytic anaemia. An in-saline agglutination test was performed (Box 33.3) and found to be strongly positive (Figure 33.1). Peripheral blood smear examination revealed a strongly regenerative anaemia with marked polychromasia and anisocytosis and an increase in nucleated red blood cells; marked spherocytosis was also identified. Platelet numbers were adequate, and a moderate subjective left-shifted neutrophilia and a monocytosis were suspected (see Ch. 3).

BOX 33.3 In-saline agglutination test for autoagglutination

One or more drops of fresh blood (or blood from an EDTA tube) are placed on a glass slide and an equal volume of normal saline added. The slide is gently rotated and then examined for evidence of macroscopic agglutination after approximately 1 minute. The slide is then examined microscopically as well (Figure 33.1). Saline is added to differentiate true agglutination from rouleaux formation. Rouleaux are chains of red blood cells stacked like coins, and are especially common in cats and animals with inflammation. They should be dissipated by the addition of saline.

Figure 33.1 Microscopic in-saline agglutination (a) ×100 and (b) ×200 magnification.

(Photographs courtesy of Kate English)

Clinical Tip

In addition to the emergency database, an in-house biochemistry profile was performed that revealed hyperbilirubinaemia (total bilirubin 45 µmol/l, reference range 2–10 µmol/l) and a mild increase in liver enzymes. Free catch urinalysis revealed a specific gravity of 1.050 and dipstick analysis showed 3+ bilirubin and 2+ haemoglobinuria; no bacteria were seen and there was a normal number of white blood cells on sediment examination. In-house blood typing was performed (RapidVet-H Canine DEA 1.1®; DMS Laboratories, New Jersey, USA) and the dog was successfully typed as DEA 1.1 positive.

Clinical Tip

Case management

A packed red blood cell transfusion was administered and the dog received a total of approximately 10 ml/kg over 6 hours. Minimum intervention was performed in the interim, and by the end of the transfusion the dog’s cardiorespiratory and mental status had improved significantly and predictably. Thoracic and abdominal radiographs were then taken and found to be sterile.

The dog was started on immunosuppressive therapy as follows:

In addition, the dog was started on aspirin (0.5 mg/kg p.o. q 24 hr) in an attempt to reduce the risk of thromboembolic disease, and maintenance isotonic crystalloid (Hartmann’s solution 2 ml/kg/hr) fluid therapy was provided initially.

The dog made good clinical progress and was discharged after 5 days of hospitalization at which time PCV was 29%, anaemia was moderately regenerative, in-saline agglutination remained mildly positive, and hyperbilirubinaemia had resolved. A comprehensive plan for on-going monitoring and adjustment of therapy was agreed with the owner.

Feline Immune-Mediated Haemolytic Anaemia (IMHA)

Primary (idiopathic) IMHA is reportedly much less commonly in cats than it is in dogs. No breed association has been reported and the possibility of PK deficiency as a differential diagnosis should be borne in mind. This red blood cell enzymopathy has been reported in Abyssinian, Somali and domestic short hair cats.

Diagnosis and treatment of IMHA in cats follow similar principles to those described for dogs although it is noteworthy that identification of spherocytes in cats is more difficult due to normal feline erythrocytes often lacking central pallor. Cats must be blood typed and given type-specific fresh whole blood (see Ch. 40). If this is not possible, Oxyglobin® (see Ch. 4) is especially useful as a substitute by providing oxygen-carrying capacity in severely anaemic cats. Cats in general, and especially anaemic cats, are prone to fluid overload and Oxyglobin® is typically administered at a conservative 0.5–1.0 ml/kg/hr for the treatment of anaemia in euvolaemic cats.

Clinical Tip

Glucocorticoid administration is the most important part of acute therapy. Azathioprine should not be administered to cats and chlorambucil (2 mg total dose p.o. q 24–72 hr) is the immunosuppressive agent of choice in this species in addition to glucocorticoid therapy.

Mycoplasma haemofelis

Mycoplasma haemofelis (previously Haemobartonella felis) infection is a cause of IMHA in cats which may be addressed specifically. Although treatment does not typically clear infection completely, parasitaemia resolves quickly and clinical improvement occurs within a few days. Diagnosis typically requires a blood sample to be submitted for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay with some delay before the results are received. The author therefore typically treats all cats with suspected primary IMHA for possible mycoplasmosis until the PCR results are received. Doxycycline (5–10 mg/kg p.o. q 12–24 hr for 10–21 days) is the preferred treatment but may be problematic to administer enterally in cats that are anorexic, especially as minimizing stress is essential in anaemic cats. If doxycycline is administered directly by mouth, a small amount (5 ml) of water must be syringed straight after to prevent the tablet becoming lodged in the oesophagus and causing a potentially serious oesophagitis. Parenteral enrofloxacin (5 mg/kg slow i.v. diluted, s.c. (or p.o.) q 24 hr) may be administered instead and is likely to be preferable in a number of these cats; the potential for enrofloxacin to cause retinal toxicity and permanent blindness in cats must not be overlooked but this has only been reported at higher doses. Immunosuppressive glucocorticoid therapy is required in the short term in cats found to have mycoplasmosis but can be tapered more quickly than for primary IMHA.

Primary (Idiopathic) Immune-Mediated Thrombocytopenia (ITP)

Thrombocytopenia may be the result of an increase in platelet destruction or consumption, a decrease in platelet production, or sequestration. In many diseases, the actual platelet count reflects a combination of more than one of these processes occurring concurrently.

Causes

Infectious diseases

Infectious causes of thrombocytopenia are usually associated with systemic signs, physical examination findings and clinicopathological abnormalities beyond thrombocytopenia alone. Examples include leptospirosis, feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) infection, feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) infection, ehrlichiosis, babesiosis and rickettsiosis.

Neoplasia

Thrombocytopenia may occur in association with a number of tumours but is most severe with tumour types that can affect haematopoiesis (e.g. lymphoma, multiple myeloma). Thrombocytopenia may also be the result of chemotherapeutic agents employed in the treatment of neoplasia.

Immune-mediated thrombocytopenia

ITP may be primary (idiopathic) or secondary to an infectious, inflammatory or neoplastic process, as well as to a variety of drug therapies. ITP occurs as a result of antibodies directed against platelet membrane antigens and subsequent phagocytosis or lysis. Primary (idiopathic) ITP is much more common in dogs than in cats, and especially occurs in females and certain breeds (e.g. the Cocker Spaniel, poodles, the Old English Sheepdog).

Clinical signs of ITP

Clinical signs of ITP are as expected with severe thrombocytopenia and include epistaxis, gingival bleeding, melaena, vomiting and possible haematemesis (see Ch. 21). Physical examination may reveal petechiae and ecchymoses, evidence of cardiorespiratory compensation for blood loss anaemia, and pyrexia. A variety of other nonspecific signs may be found.

Diagnosis of ITP

Animals with ITP typically have very severe thrombocytopenia; machine platelet counts are typically less than 10 × 109 platelets/litre, and peripheral smear examination may reveal no platelets at all or an average of less than 1 platelet per high-power (×100) field. The diagnosis of ITP is routinely made on the basis of identifying a thrombocytopenia of this severity in an animal with compatible clinical signs. Thereafter, investigations are performed to identify a primary cause and if one cannot be found, a presumptive diagnosis of ITP is made.

Occasionally dogs with ITP are also found to have evidence of immune-mediated red blood cell destruction and these dogs are therefore classified as having Evans’ syndrome. Nevertheless, management of these cases is the same as for ITP and IMHA.

Treatment of ITP

Immunosuppressive therapy using corticosteroids is the mainstay of therapy for ITP and is similar to treatment for IMHA; additional immunosuppressive therapies may be included (see Box 33.2). Animals with secondary immune-mediated platelet destruction may also require more short-term corticosteroid therapy in addition to specific treatment for the primary disorder.

Vincristine may be used to promote the release of functional platelets from the bone marrow but the author typically only uses this agent in cases that fail to show signs of improvement on corticosteroid alone. Human intravenous IgG has also been used but is very expensive and has limited availability.

Packed red blood cell or fresh whole blood transfusions may be required in animals with sufficiently severe gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Platelet transfusions are often discussed and may be provided using fresh whole blood, platelet-rich plasma or platelet concentrates. The availability of the latter in particular is likely to increase with time. However, platelet transfusions are typically discouraged in dogs with ITP; the transfused platelets are also susceptible to antibody binding and will very likely have a short lifespan of less than 1 day and perhaps as short as a few minutes only. The use of platelet transfusions as a short-term, potentially life-saving measure in dogs with severe bleeding may become more practical in the future.

Supportive intravenous crystalloid therapy, gastroprotectants, antiemetics and other symptomatic treatments may be required in the early stages of treatment.

Clinical Tip

Canine Angiostrongylus vasorum Infection

Theory refresher

Angiostrongylus vasorum (canine lungworm) is a metastrongylid helminth infecting domestic dogs as well as foxes. Molluscs (snails, slugs) act as intermediate hosts. Larvae ingested in molluscs generally migrate from the small intestine to the right ventricle and pulmonary vasculature where they mature to adulthood. However, extensive aberrant larval migration into many body organs and tissues has been documented. Angiostrongylus vasorum has a worldwide distribution, and infections are continuously being identified in new areas both within the United Kingdom and globally.

Clinical signs

A wide variety of clinical signs has been reported but most dogs diagnosed with clinically significant disease have respiratory signs, bleeding disorders or neurological signs. Ocular signs, including intraocular larval migration, have also been reported relatively frequently. However, aberrant systemic dissemination of the larvae means that additional syndromes as a result of haemorrhage, granulomatous inflammation or infarction at other sites may well be recognized more commonly in the future. Respiratory signs are the result of pulmonary inflammation secondary to both eggs and to larval migration through the parenchyma. Over time, pulmonary hypertension may develop, resulting in right-sided cardiac changes (cor pulmonale).

Neurological signs associated with angiostrongylosis may occur as a result of larval migration through, or bleeding into, the central nervous system; both abnormalities have been documented. Reported neurological signs include reduced mentation from depression through to coma, behavioural changes, seizures and loss of vision related to brain involvement; and spinal and neck pain, ataxia, and paresis or plegia related to spinal cord involvement.

The mechanism(s) of coagulation defects due to Angiostrongylus vasorum remain to be clarified. Although many dogs have variably abnormal coagulation tests, the author has certainly seen cases in which routinely available means of evaluating coagulation (platelet count, buccal mucosal bleeding time, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time) have been within normal limits despite clinical evidence of coagulopathy. The same is true for a small number of cases in which D-dimers/fibrin degradation products (FDPs) and von Willebrand factor levels have been measured. A chronic intravascular consumptive coagulopathy (chronic disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)) has been suggested as a mechanism by some authors.

Angiostrongylosis has been diagnosed in dogs with a variety of clinical presentations of bleeding, including:

Although neoplastic rupture is the most common cause of spontaneous haemoabdomen, this typically occurs in older dogs. Angiostrongylosis should therefore be considered especially in young dogs presenting with spontaneous haemoabdomen (as well as anticoagulant rodenticide intoxication for example, see Ch. 30).

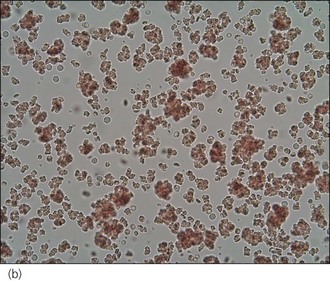

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of canine angiostrongylosis is currently made most reliably by faecal analysis or cytology on airway samples (transtracheal wash, tracheal wash via endotracheal tube or bronchoalveolar lavage). In-house faecal smear examination (Box 33.4) allows diagnosis to be made on an emergency basis and, in the author’s experience, the diagnosis can be made in most dogs with clinical angiostrongylosis on the basis of faecal smear examination, albeit that in some cases multiple smears may need to be examined (see Figure 33.2). Faecal analysis via Baermann faecal flotation is currently the most reliable method available although this clearly involves some delay before results are received. In the author’s opinion, treatment should be implemented before results are received in cases in which there is a high index of suspicion for angiostrongylosis but faecal smear examination is negative or cannot be performed. Serology for detecting antibodies against Angiostrongylus vasorum antigen is now available and likely to become more widely used in the future.

BOX 33.4 Faecal smear preparation for detection of Angiostrongylus vasorum larvae

In an emergency scenario, faeces for examination is often obtained via manual removal from the rectum and as such, only a small amount may be available. In such cases, it is most appropriate to smear the faeces directly on to one or more slides, add a small amount of water to the slide, cover the slide with coverslips (if available), and examine microscopically using a low (×20) magnification with the condenser down.

If a larger amount of faeces is available, the faeces should be placed in a container to which water is then added. The solution is mixed thoroughly and multiple smears are then made for microscopic examination.

Angiostrongylus vasorum larvae have a characteristic appearance and should not be mistaken for hairs which are straight with a line down the middle (Figure 33.2).

Treatment

Treatment of canine angiostrongylosis is described in Case example 2. In addition, both total and ionized hypercalcaemia have been reported in dogs with angiostrongylosis and may be sufficiently severe as to require specific intervention (0.9% sodium chloride diuresis, furosemide). Hypercalcaemia is thought to be due to granulomatous inflammation and should resolve fully with successful anthelminthic therapy.

Case example 2

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 2-year-old male neutered English Mastiff dog presented with a 3-day history of progressive respiratory distress, coughing (haemoptysis), excessive panting, exercise intolerance, lethargy and inappetence. The dog was known to be a scavenger but no other significant previous history was reported. Deworming therapy had not been administered since puppyhood.

Major body system examination

On presentation the dog was ambulatory but weak. Cardiovascular examination revealed a heart rate of 135 beats per minute with good peripheral pulses; heart sounds could not be reliably heard. Mucous membranes were pink with a normal capillary refill time. The dog was panting but there was also a notable increase in respiratory effort and lung sounds were diffusely harsh bilaterally. Abdominal palpation was compromised by the dog’s size but no obvious abnormalities were detected. Rectal temperature was markedly elevated at 39.8°C but rectal examination was otherwise unremarkable. As much faeces as possible was removed manually at this time for further analysis. No other abnormalities were detected on physical examination. Pulse oximetry was attempted but a reliable measurement could not be obtained. Body weight was 75 kg.

Assessment

The dog was identified as being in respiratory distress and the degree of respiratory noise obscured auscultation of the heart sounds. However, it was not felt appropriate to stop the dog from panting. Systemic perfusion appeared normal on physical examination and it was therefore suspected that the dog’s respiratory compromise was more likely to be of primary respiratory rather than cardiac origin. The history of haemoptysis provided further support for this assessment; while coughing is often the result of cardiac disease, haemoptysis would be considered unusual. The elevated rectal temperature could have been the result of both hyperthermia secondary to respiratory distress, especially given the dog’s breed, and pyrexia resulting from the underlying disorder.

Emergency database

Flow-by oxygen supplementation was commenced and an intravenous catheter placed into one of the cephalic veins. Blood was collected via the catheter for an emergency database that revealed mild anaemia (manual PCV 32%, reference range 37–55%) with raised serum total solids (80 g/l, reference range 49–71 g/l). Peripheral blood smear evaluation was suggestive of a mildly regenerative anaemia (based on the degree of polychromasia and anisocytosis – see Ch. 3) and showed adequate platelet numbers, a subjective moderate mature neutrophilia and a subjective mild eosinophilia. The regenerative anaemia was suspected to be the result of blood loss, with serum total solids being increased as a result of hyperglobulinaemia, the latter being relatively common in angiostrongylosis. Facilities were not available to measure either clotting times or serum calcium concentration.

While the dog continued to receive oxygen supplementation, a direct faecal smear was examined and found to contain a large number of Angiostrongylus vasorum larvae (Figure 33.2). The remainder of the faecal sample was submitted for a Baermann faecal flotation to be performed; this was not to confirm the diagnosis that had already been made, but rather to assess more accurately the severity of the worm burden and provide a means of more reliably monitoring response to therapy.

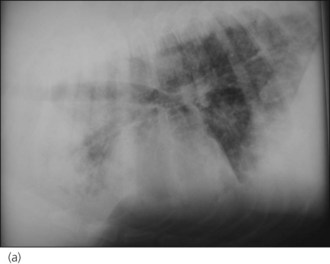

Case management

A diagnosis of severe parasitic pneumonia secondary to Angiostrongylus vasorum infestation was made. As the dog was very amenable, thoracic radiographs were taken following administration of butorphanol (0.2 mg/kg i.v.) with oxygen supplementation throughout and revealed a generalized interstitial to alveolar lung pattern (Figure 33.3). The distribution of the lung changes was considered to be most consistent with parasitic pneumonia.

Figure 33.3 (a) Right lateral and (b) dorsoventral thoracic radiographs from a dog with Angiostrongylus vasorum infection; a generalized interstitial to alveolar lung pattern is present.

Clinical Tip

The dog was maintained initially on nasal oxygen supplementation using bilateral indwelling nasal oxygen catheters (see Ch. 6). Given the severity of the parasite burden, he was treated with both milbemycin oxime/praziquantel (Milbemax®, Novartis Animal Health, Frimley, UK) at a dose of three tablets (approximately equal to 0.5 mg/kg milbemycin and 125 mg/kg praziquantel) as a single dose once weekly for 4 weeks, and imidacloprid/moxidectin (Advocate Spot-on solution®, Bayer plc, Newbury, UK) as a single dose of 7.5 ml (10 mg/kg imidacloprid and 2.5 mg/kg moxidectin) applied topically. Dexamethasone (0.1 mg/kg i.v. q 24 hr) was also administered for the first few days in an attempt to reduce the pulmonary inflammatory reaction associated with dying Angiostrongylus vasorum larvae.

The dog made gradual improvement and was weaned off oxygen supplementation over a period of 48 hours. He was eventually discharged after being hospitalized for 7 days with instructions to keep him strictly rested and to prevent scavenging, and went on to make a full recovery. His owner was advised both regarding on-going prophylaxis once treatment had been completed and with respect to treatment of the other dog in the household due to a high likelihood of infection in that dog as well.

Clinical Tip

Clinical Tip