12 Cardiac dysrhythmias

Cardiac dysrhythmias are a relatively common finding in emergency patients and are probably also underdiagnosed in general. Physical examination may generate the suspicion of a dysrhythmia (e.g. heart rate that is pathologically fast or slow, pulse deficits), but this can only be confirmed using electrocardiography. A wide variety of dysrhythmias exist and a full discussion is beyond the scope of this book. This chapter presents some of the most common dysrhythmias that the author sees, focusing on dogs, and summarizes the recommendations for their management.

Normal Cardiac Conduction

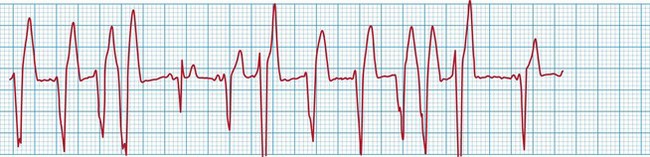

An impulse is normally generated at the sinoatrial (SA) node which is the dominant pacemaker. The impulse is conducted from there across the atria to the atrioventricular (AV) junction and into the AV node; it then passes down the bundle of His and bundle branches, on to the Purkinje fibres. The overall result is cardiac contraction. Impulse conduction is reflected as the normal sinus beat (P-QRS-T) and normal sinus rhythm results from impulses being generated at the SA node at a normal rate (Figure 12.1).

Figure 12.1 Normal sinus rhythm in a dog showing P-QRS-T complexes (lead II, 25 mm/s).

(Courtesy of Simon Dennis)

Clinical Tip

Tachydysrhythmias

Supraventricular tachycardia

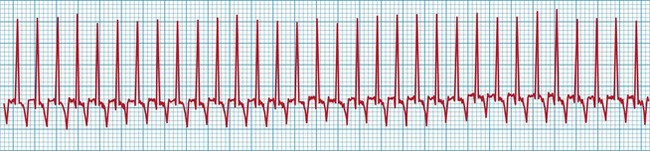

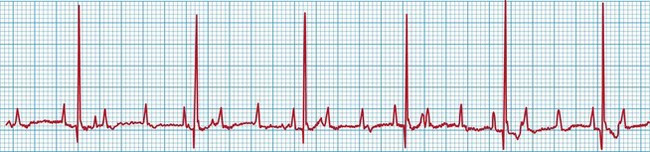

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) may be atrial or junctional in origin and can be difficult to distinguish from ventricular tachycardia in some cases. On physical examination both may have rapid weak pulses with pulse deficits. Potential distinguishing features for SVT (Figure 12.2) on electrocardiography include:

Figure 12.2 Supraventricular tachycardia in a dog at a rate of approximately 320 beats per minute (lead II, 25 mm/s). QRS complexes look relatively normal (tall, narrow, uniform) with a regular R-R interval.

(Courtesy of Simon Dennis)

It is noteworthy that physiological or appropriate sinus tachycardia, including in response to severe hypovolaemia, rarely exceeds a rate of 220–240 beats per minute in dogs at rest (300 beats per minute in cats); heart rate may exceed this in dogs such as greyhounds during intense exercise. The finding of a heart rate above this level should prompt electrocardiography.

Causes

Supraventricular tachycardias most commonly occur as a result of primary cardiac disorders that result in atrial dilation (e.g. mitral or tricuspid regurgitation). Some animals present in congestive heart failure.

Indications for treatment

Supraventricular tachycardia should be treated with specific anti-dysrhythmic therapy if treatment of congestive heart failure does not improve the dysrhythmia and it is deemed to be clinically significant.

Treatment

Although conversion to sinus rhythm is preferred, this is not always possible and the main aim of treatment is to slow the ventricular response rate such that the dysrhythmia no longer causes haemodynamic compromise. Oral digoxin and treatment for congestion are implemented in animals with congestive heart failure. The reader is referred to other sources for more information on the use of digoxin.

Vagal manoeuvres can be attempted and may be effective in some animals with SVT. This involves carotid sinus massage or applying pressure to the closed eyes. If vagal manoeuvres fail and treatment of congestion alone is ineffective, then additional medical therapy may be indicated. Diltiazem (a calcium channel blocker) is the most commonly used agent and may be given intravenously if available or orally. This agent must be used cautiously in animals with congestive heart failure if at all as it has negative inotropic effects that may cause clinical deterioration.

Atrial fibrillation

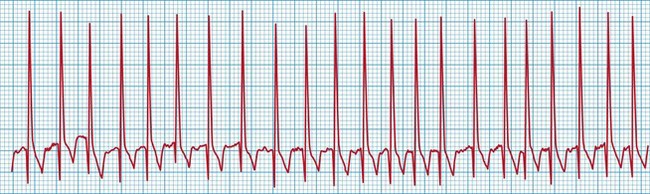

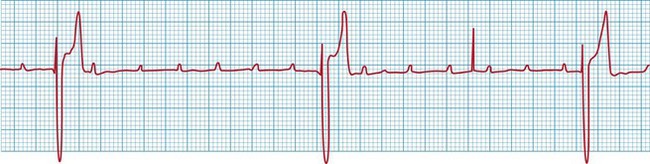

Atrial fibrillation (AF) (Figure 12.3) is characterized by a chaotic irregularly irregular heart rhythm on auscultation with marked pulse deficits. Electrocardiography shows:

Figure 12.3 Atrial fibrillation in a dog at a rate of approximately 240 beats per min (lead II, 25 mm/s). QRS complexes look relatively normal (tall, narrow, uniform) but with an irregularly irregular R-R interval.

(Courtesy of Simon Dennis)

Causes

In emergency practice, AF is typically (although not always) seen in animals with severe primary structural heart disease, usually involving atrial dilation. The ventricular rate in such cases is typically fast (potentially over 200 beats per minute), and there is usually evidence of congestive heart failure (see Ch. 31). Lone AF is used to describe AF in dogs without evidence of structural heart disease (e.g. some Irish Wolfhounds). AF does occur in cats but less frequently than in dogs.

Indications for treatment

The approach to AF will depend on the rate, the underlying cause, and whether congestive heart failure is present. Stabilization of congestive heart failure is the priority, and treatment to control the ventricular response rate may then be included in subsequent therapy if still required.

Treatment

Treatment of AF is designed to slow the heart rate (typically to less than 160 beats per min in dogs) in order to improve cardiac output. However, as animals with severe heart failure may require some degree of heart rate elevation to maintain cardiac output, excessive reduction of ventricular response rate may not be desirable. Conversion to sinus rhythm is difficult and in fact not shown to be associated with any additional benefit.

Oral digoxin is the usual agent of choice for dogs with heart disease and the reader is referred to other sources for more information on the use of digoxin. Congestion should also be treated as required (see Ch. 31). Occasionally additional antidysrhythmic therapy (e.g. oral diltiazem) is indicated if treatment of congestion does not provide adequate ventricular rate control but care with dosing must be taken in animals with congestive heart failure.

Ventricular tachycardia

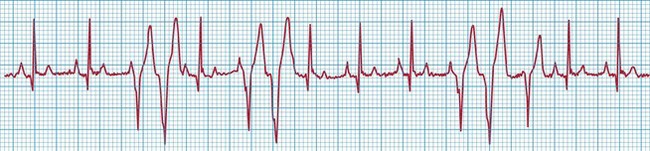

Ventricular premature complexes (VPCs) and ventricular tachycardia (VT) are commonly identified in emergency patients, especially dogs (Figures 12.4 and 12.5). VT is seven or more consecutive ventricular premature complexes. Complexes are usually wide and bizarre, and not associated with P waves.

Figure 12.4 Ventricular premature complexes in a dog (lead II, 25 mm/s); two couplets and a triplet are present. The QRS complexes are wide and bizarre, and not related to the normal P waves.

(Courtesy of Simon Dennis)

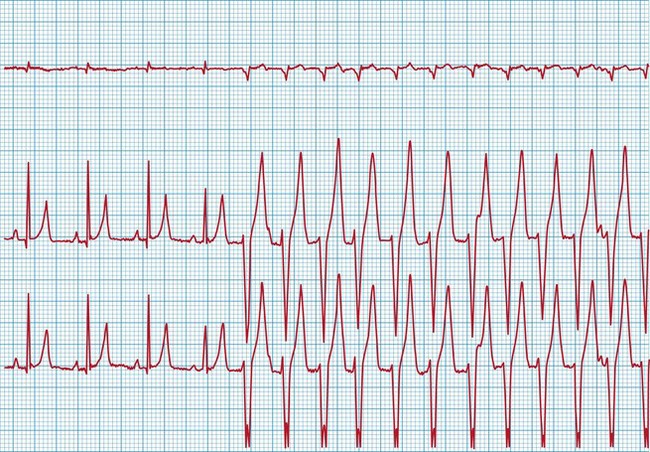

Figure 12.5 Ventricular tachycardia in a dog at a rate of approximately 180 beats per minute (leads I–III, 25 mm/s); QRS complexes appear uniform (monomorphic morphology) and R-on-T is not present.

(Courtesy of Simon Dennis)

Causes

These dysrhythmias may occur secondary to a large number of noncardiac disorders, but may also be the result of primary heart disease. Causes of VPCs and VT are summarized in Box 12.1.

BOX 12.1 Causes of ventricular premature complexes (VPCs) and ventricular tachycardia (VT) in companion animals

Clinical Tip

Indications for treatment

Ventricular premature complexes typically do not require specific intervention and treatment is aimed at the underlying disorder. VT is only treated when one of the following criteria is met:

Figure 12.6 R-on-T phenomenon in a dog (lead II, 25 mm/s); the fourth ectopic R wave (from the left) is superimposed on the T wave of the preceding complex. This occurs again towards the end of the ECG strip.

(Courtesy of Virginia Luis Fuentes)

An accelerated idioventricular rhythm refers to a ventricular rhythm occurring at a slower rate than VT, typically less than 100–140 beats per minute (definitions vary). QRS complexes are typically regular and uniform. Causes include major surgical procedures or other trauma, and systemic disease. Accelerated idioventricular rhythm does not typically cause haemodynamic compromise and therefore does not usually require treatment.

Treatment

Clinical Tip

Lidocaine is usually the first drug used for VT that is assessed to require treatment. In dogs, a bolus of 2 mg/kg is administered slowly intravenously; if there is no response to the first bolus after 2–3 minute, a further three boluses may be attempted (i.e. total dose of 8 mg/kg); if there is a positive response, a constant rate infusion is started (50–80 µg/kg/min). Lidocaine may be less effective in the presence of hypokalaemia.

If the dysrhythmia fails to respond to lidocaine, and the clinician is sure that the dysrhythmia is not in fact an SVT, then alternative agents may be tried; however, this may be constrained by what agents are available within the practice. Sotalol and procainamide may both be given intravenously and the former is usually the author’s next choice after lidocaine.

In animals with VT as a result of primary cardiac disease, appropriate long-term medications are also started and these may include oral antidysrhythmic therapy (e.g. sotalol, mexiletine). In animals with secondary VT, it is very unusual to need to provide anything more than a lidocaine infusion for 24–72 hr while the primary disorder is treated or the animal is recovering following treatment.

Brady-dysrhythmias

Clinical Tip

Sinus brady-dysrhythmias

Sinus brady-dysrhythmias occur as a result of decreased impulse generation by the SA node or decreased conduction of the impulse through the atria. Sinus bradycardia, sinus arrest and SA block are types of sinus brady-dysrhythmia.

Causes

Sinus brady-dysrhythmias may occur as a result of primary cardiac or noncardiac causes. Systemic diseases (e.g. central nervous system disorders, gastrointestinal disorders) that result in high vagal tone are a relatively common cause in emergency patients, as are hypothermia and hypoglycaemia. Vagal involvement can potentially be confirmed by assessing response to vagolytic therapy (atropine, glycopyrrolate) although there may be some variation in individual patient response. Sinus brady-dysrhythmias may also occur secondary to administration of a variety of drugs, some of which are used commonly in emergency cases (e.g. opioids, sedatives); however, this is only likely to be clinically significant in excessive doses. Primary cardiac causes of sinus brady-dysrhythmias typically relate to disease of the SA node (e.g. idiopathic fibrosis, myocardial disease).

Sick sinus syndrome

Sick sinus syndrome (SSS) refers to a combination of dysrhythmias that typically include abnormalities in both impulse generation by the SA node and subsequent conduction. Sinus bradycardia, sinus arrest and SVT occur in variable combinations. This disorder is usually idiopathic and occurs most commonly in the West Highland White terrier and the Miniature Schnauzer amongst others. The syndrome has not been reported in cats thus far.

Indications for treatment

Treatment is typically indicated in all dogs that are symptomatic for SSS. Common clinical signs of low cardiac output include cardiac syncope as well as exercise intolerance and variable weakness.

Treatment

In less severe cases of SSS, it may be appropriate to attempt medical therapy (e.g. terbutaline, theophylline) and some clinical improvement may be observed, at least for a short while. In more severe cases, referral for pacemaker implantation is required and this may need to be arranged on an urgent emergency basis.

Atrioventricular block

AV block refers to delayed or failed impulse conduction through the AV node. There are three types of AV block – first degree, second degree and third degree (see Figures 12.7-12.9) – with some further subclassification.

Figure 12.7 Second degree AV block in a dog (lead II, 25 mm/s); every third P wave is conducted and associated with a QRS complex (3 to 1 conduction).

(Courtesy of Simon Dennis)

Figure 12.8 Low-grade second degree AV block in a dog (lead II, 25 mm/s); the majority of P waves are conducted and associated with a QRS complex.

(Courtesy of Simon Dennis)

Figure 12.9 Third degree AV block in a dog (lead II, 25 mm/s). There is no P wave conduction and the QRS complexes are ventricular (wide and bizarre), occurring at a rate slower than the P waves; the ventricular escape rate is approximately 30 beats per minute.

(Courtesy of Simon Dennis)

Causes

High vagal tone is a relatively common cause of AV block, which may also result from hyperkalaemia and excessive doses of certain drugs. As with SA node disease, primary disease of the AV node (e.g. idiopathic fibrosis, myocardial disease) can also cause AV block. Third degree AV block is almost always due to heart disease.

Indications for treatment

Specific treatment of AV block is only indicated if the animal is deemed to be symptomatic from the dysrhythmia. Otherwise treatment is aimed at addressing the underlying cause. First degree AV block is unlikely to cause clinical signs, but second degree AV block may be clinically significant. Third degree AV block is almost always associated with haemodynamic compromise and causes signs such as exercise intolerance, variable weakness and cardiac syncope.