31 Cardiovascular emergencies

Acute Decompensated Heart Failure

Progressive heart disease results in failure of the heart to pump adequately and this may manifest as low-output heart failure, where sufficient blood is not pumped into the aorta or pulmonary artery, or congestive heart failure (CHF). In CHF, there is inadequate emptying of blood from the venous system: left-sided CHF results in congestion of the pulmonary circulation with pulmonary oedema; right-sided CHF causes congestion of the systemic circulation with ascites and pleural effusion. Bilateral heart failure presents with a combination of both types of signs.

Failure of the heart to pump adequately may result from systolic dysfunction, i.e. the heart is physically unable to eject enough blood, or from diastolic dysfunction, i.e. the ventricles are unable to fill properly. Both mechanisms are often involved and the end result is reduced cardiac output and a lowering of arterial blood pressure. Systolic dysfunction may result from failure of the myocardium itself (e.g. dilated cardiomyopathy), from an increase in ventricular pressure (pressure overload; e.g. pulmonic stenosis, subaortic stenosis) or from volume overload (e.g. atrioventricular valve disease). Diastolic dysfunction (impaired ventricular filling) may result, for example, from ventricular hypertrophy, dilated cardiomyopathy, atrioventricular valve stenosis or pericardial effusion (cardiac tamponade).

Compensatory mechanisms during heart disease include mechanisms relating to the heart itself, such as tachycardia, increased inotropy (force of contraction) and myocardial hypertrophy, and peripheral compensation involving vasoconstriction and sodium and water retention. In time these compensatory mechanisms become detrimental.

Treatment

Although signalment and history may help to some small degree, emergency treatment of animals with acute decompensated heart failure often needs to be performed without a definitive diagnosis of the nature of the underlying heart disease. Management of such cases may involve:

The use of additional agents such as sodium nitroprusside or dobutamine may be indicated in some cases but is likely to be restricted to referral institutions.

Canine chronic mitral valve insufficiency

Theory refresher

Chronic mitral valve insufficiency is usually the result of progressive valvular myxomatous degeneration and has a high prevalence in older dogs, especially of small to medium size. The most commonly affected breeds include the Cavalier King Charles spaniel, terrier breeds and poodles. The disease usually progresses over a period of years and is the most common cause of CHF in dogs.

In the long term, mitral regurgitation results in tachycardia, myocardial hypertrophy and reduced myocardial contractility; left atrial size and pressure increase, and pulmonary venous congestion and oedema may occur. Coughing may be the result of left main stem bronchus compression by the enlarged left atrium and/or pulmonary oedema.

Acute severe decompensated heart failure may occur in dogs with mitral valve insufficiency due to:

Case example 1

Presenting Signs and Case History

An 11-year-old male neutered Norfolk terrier presented following an episode of collapse and onset of severe respiratory distress. The dog had had a number of similar episodes in the 2 weeks prior to emergency presentation but none had been as severe as the most recent one. He had a history of chronic mitral valve insufficiency and CHF for which he was receiving furosemide, pimobendan and benazepril. The owner reported a variable appetite recently and admitted that she had not managed to administer all of the dog’s medications as directed. No other significant preceding history was reported.

Major body system examination

On presentation the dog was alert but clearly in respiratory distress. Flow-by oxygen supplementation was commenced while a major body system examination was performed. Cardiovascular examination revealed a heart rate of 160 beats per minute with a grade VI/VI left apical systolic murmur that had wide radiation. Femoral and dorsal pedal pulses were very weak but pulse deficits were not detected. The jugular veins did not appear distended. Mucous membranes were hyperaemic with a fast capillary refill time.

Respiratory rate was 60 breaths per minute and there was a notable increase in effort. Lung sounds were diffusely harsh bilaterally and focal patches of crackles were audible. The dog’s abdomen was distended with a fluid thrill and rectal temperature was within normal limits. Blood pressure via Doppler sphygmomanometry was within normal limits at 130 mmHg.

Assessment

The dog’s cardiovascular examination revealed tachycardia and marked hypoperfusion as well as a maximal grade heart murmur. Putting this together with the respiratory findings and the dog’s history, a diagnosis of decompensated CHF was most likely. The possible pulmonary oedema suggested left-sided heart failure, and the fluid thrill may have suggested a degree of right-sided failure as well.

Emergency database

As the dog remained tolerant and compliant with the flow-by oxygen supplementation, an intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and blood obtained via the catheter for an emergency database. This revealed mild hyponatraemia (137.0 mmol/l, reference range 140.0–153.0 mmol/l) and a mild increase in blood urea nitrogen (13.0 mmol/l, reference range 3.0–10.0 mmol/l) but was otherwise unremarkable.

Case management

Glyceryl trinitrate 2% paste (18 mm) was applied to the inner aspect of the dog’s right pinna and he was then placed into an oxygen cage with continuous electrocardiographic monitoring; this showed the dog to be in sinus tachycardia. Furosemide (4 mg/kg i.v.) and morphine (0.1 mg/kg slow i.v.) were administered via an extension line exiting the oxygen cage. Ad lib water was provided.

Clinical Tip

One hour later the dog’s respiration had improved to some extent and he had also urinated. As he was compliant, thoracic radiographs were performed with flow-by oxygen supplementation throughout (Figure 31.1). These findings were consistent with the suspected diagnosis of decompensated left-sided CHF secondary to probable mitral valve insufficiency but there was also evidence of right-sided heart failure.

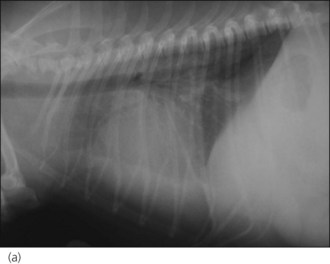

Figure 31.1 (a) Right lateral and (b) dorsoventral thoracic radiographs of a dog with end-stage mitral valve disease showing cardiomegaly with left atrial enlargement and dorsal displacement of the caudal part of the trachea, an alveolar lung pattern affecting mainly the cranial lung lobes with air bronchograms, mild bilateral pleural effusion and hepatomegaly.

Clinical Tip

The dog was returned to the oxygen cage and continued to be treated with intermittent intravenous boluses of furosemide (2–6 mg/kg q 1–2 hr, prn) and morphine (0.1 mg/kg slow i.v. q 6 hr). Glyceryl trinitrate paste (18 mm q 8 hr) was also applied and the dog was continued on oral pimobendan and benazepril.

Although the dog showed some early improvement, his clinical condition deteriorated again. The owners were offered the option of an emergency referral to a hospital with a cardiologist and facilities to offer more intensive management but decided instead to have the dog euthanased which was therefore done in their presence as soon as possible.

Canine tricuspid valve insufficiency

Tricuspid valve insufficiency is often an incidental finding in dogs and cats. Clinically significant tricuspid valve insufficiency may be seen with:

Right atrial enlargement may result in supraventricular tachydysrhythmias, and increased right atrial pressure may result in ascites, pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, hepatomegaly and splenomegaly. From an emergency perspective, animals with tricuspid valve insufficiency are more likely to require treatment for a concurrent disorder than for primary right-sided heart failure.

Canine dilated cardiomyopathy

Theory refresher

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a primary myocardial disease characterized by enlargement of the heart, reduced systolic function and possible impaired diastolic function. The disease is seen most commonly in adult large and medium size dogs, with some breeds being over represented (e.g. the Great Dane, the Doberman Pinscher, the Irish Wolfhound, the Cocker Spaniel). There is significant variation between breeds with respect to both historical and clinical findings, and rate of disease progression.

DCM is definitively diagnosed by echocardiography that shows left (and perhaps bilateral) atrial and ventricular enlargement, and evidence of reduced left ventricular systolic function. Mitral regurgitation may be identified in association with the dilated left ventricle.

Case example 2

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 6-year-old male neutered Great Dane presented with a 10-day history of inappetence and retching that was worse when the dog was lying down. There had been some noticeable exercise intolerance on daily walks and the owner had noticed that the dog had a very fast heart rate prompting emergency presentation. The dog had had surgical treatment of gastric dilatation/volvulus syndrome 2 years previously but no other significant history was reported.

Major body system examination

On presentation the dog was ambulatory but quiet. Cardiovascular examination revealed an irregularly irregular heart rhythm with a left apical grade II/VI systolic heart murmur. Femoral pulses were weak and there were marked pulse deficits: heart rate 240 beats per minute, pulse rate 114 per minute. Mucous membranes were hyperaemic with a fast capillary refill time.

The dog was panting but it was decided not to stop this in order to auscultate the lung fields at initial presentation. Abdominal palpation was unremarkable but there was a mild increase in rectal temperature (39.5°C). Blood pressure via Doppler sphygmomanometry was within normal limits at 160 mmHg.

Assessment

The dog’s cardiovascular examination was highly suggestive of atrial fibrillation and the history of inappetence and exercise intolerance most likely suggested a degree of CHF. Given the dog’s breed, there was a high index of suspicion for DCM. The mild increase in rectal temperature was suspected to represent hyperthermia rather than pyrexia.

Emergency database

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and blood obtained via the catheter for an emergency database. This was essentially unremarkable. Electrocardiography confirmed the presence of atrial fibrillation (see Ch. 12) with a ventricular response rate of approximately 220 beats per minute.

Case management

The dog was suitably compliant (a gentle giant!) so thoracic radiographs were taken to look for evidence of CHF and evaluate the size of the cardiac silhouette (Figure 31.2). The dog was subsequently started on furosemide (2 mg/kg p.o. q 12 hr) and digoxin (0.1 mg/m2 p.o. q 12 hr) and referral arranged to a cardiologist for echocardiography and implementation of further management. This confirmed the suspicion of DCM with left atrial enlargement and pimobendan (0.125 mg/kg p.o. q 12 hr, 1 hour before feeding) and benazepril (0.25 mg/kg p.o. q 24 hr) were dispensed. The dog’s ventricular response rate had reduced to 160 beats per minute when he was seen at the referral centre (5 days after digoxin was commenced) and additional antidysrhythmic therapy was not therefore indicated.

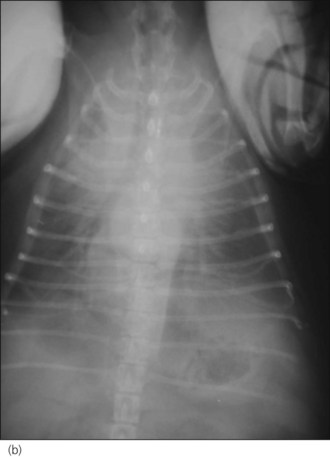

Figure 31.2 (a) Right lateral and (b) dorsoventral thoracic radiographs of a dog with dilated cardiomyopathy and mild pulmonary oedema. Peribronchial infiltrates are present throughout the lung, with patchy alveolar infiltrate in the caudoventral lung field.

Clinical Tip

Feline cardiomyopathies

Cardiomyopathy (i.e. primary disease of the myocardium rather than valvular disease) is the main form of heart disease in cats and is classified as follows:

HCM is the most commonly diagnosed feline heart disease and is inherited in some breeds (e.g. the Maine coon). The disease is associated with ventricular thickening and in some cats systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve is identified on echocardiography (so-called hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy). Systemic thromboembolism is a potential and very serious consequence of HCM in cats (see below).

Clinical Tip

Feline DCM may be caused by taurine deficiency (predominantly nutritional but there may be genetic involvement) but idiopathic feline DCM is now the most common form. Severe myocardial failure may exist for a prolonged period before signs of heart failure are seen.

Congestive heart failure in cats

Due to the difference in lifestyles between the species, cats are more likely than dogs to present for veterinary attention only when they are in severe heart failure; cats are not usually exercised directly by owners and often have a more sedentary existence, therefore clinical abnormalities may be hidden for some time. It is nevertheless important to remember that the underlying cardiomyopathy will most likely have been chronically progressive and that subtle signs of heart failure may have been present for some time.

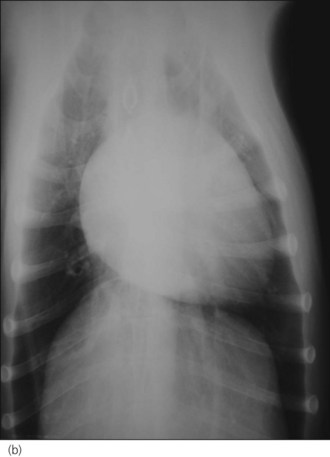

Pleural effusion is common in cats with CHF but this is rarely due to right-sided failure alone and the exact mechanism remains unclear. The nature of the pleural effusion may vary (modified transudate, pseudochylous, chylous) and heart failure is the most common cause of chylothorax in cats. Most cats have bilateral or left-sided disease and pulmonary oedema is usually present, even if it is harder to detect due to the pleural effusion (Figure 31.3).

Figure 31.3 Right lateral thoracic radiographs of a cat with congestive heart failure; cardiomegaly and pulmonary oedema are present.

In the nonreferral setting, treatment of acute decompensated CHF in cats is similar to that in dogs, namely oxygen supplementation, furosemide, glyceryl trinitrate and possibly morphine. Thoracocentesis is often required and a diagnostic procedure based on a sufficient index of suspicion is preferable to subjecting the cat to the stress of radiography; ultrasonography is a much less stressful way to identify pleural effusion, especially if a mobile machine is available (see Ch. 32).

Clinical Tip

Feline Aortic Thromboembolism (Saddle Thromboembolism)

Theory refresher

The majority of cats with aortic thromboembolism (ATE) have cardiomyopathy, often HCM, which most commonly includes left atrial enlargement. Spontaneous echo contrast may be seen in the left atrium suggesting an increased risk of thromboembolism. Feline ATE may also occur with other forms of heart disease as well as in association with hyperthyroidism (potentially independently of the cardiac effects of this disorder) and neoplasia. ATE is more common in male cats, predominantly due to their greater predisposition to HCM.

Thrombi usually form in the left atrium, become dislodged, and then cause occlusion at a distal systemic site. Thrombi may also form in the other cardiac chambers. Clinical signs associated with systemic thromboembolism in general depend on:

Clinical Tip

Treatment

Clinical Tip

Thrombolysis

Definitive therapy of ATE has been attempted using exogenous thrombolytic agents (e.g. tissue-plasminogen activator (t-PA), streptokinase). However, no consistently successful results have been reported and complications include excessive haemorrhage, reperfusion syndrome with severe hyperkalaemia and metabolic acidosis, and sudden death. Mortality rates associated with treatment are high and in the author’s opinion currently available thrombolytic agents should not be used. Mortality and complication rates are also high for balloon embolectomy, rheolytic thrombectomy and surgical thrombus removal. In all cases recurrent thrombosis may occur.

Anticoagulation

Although there is no evidence for a beneficial effect in feline ATE, aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), unfractionated heparin, and more recently low molecular weight (fractionated) heparins (e.g. dalteparin) are agents commonly employed to try to prevent further thrombus formation. Other agents such as clopidogrel have also been used.

Vasodilation

Vasodilatory agents are also often employed in the acute stages in an attempt to improve perfusion to the affected limbs. Acepromazine is commonly chosen and may also help to reduce anxiety by providing sedation. Given the potential for this agent to cause hypotension, careful rational dosing is mandatory.

Heart disease and failure

Medical therapy for heart disease, including appropriate treatment of heart failure, should be provided as indicated (see above). Initial stabilization in cats suffering from acute decompensated CHF must take priority over therapy for aortic thromboembolism.

Nursing Aspect

Cats with ATE require intensive nursing and suitable husbandry. Bedding should be clean, dry and well padded. Physiotherapy of the pelvic limbs is essential to minimize the effects of disuse. These cats may also be anorexic and placement of a nasooesophageal feeding tube may be required. Placement of other types of feeding tube will necessitate general anaesthesia which is undesirable in cats with heart disease. As the majority of cats with ATE have heart disease, minimum stress is important. That said, these cats may also be anxious and distressed by virtue of their predicament and regular fuss and attention are likely to prove beneficial.

Prognosis

In some cats limb sensation and function return rapidly (within several hours to a few days) following ATE due to intrinsic thrombolysis. Other cases may regain complete or partial limb sensation and motor function in time (often weeks to months) with adequate care. Finally, in a few cats, changes are irreversible, and cutaneous and muscular ischaemic necrosis develops. This variability in progression makes reliable prognostication with respect to pelvic limb compromise difficult in individual cases. Partial obstruction is likely to have a better prognosis than complete obstruction.

The high likelihood of underlying cardiomyopathy, the need for on-going medical therapy, and the possibility of recurrent ATE must be borne in mind. Nevertheless, a proportion of cats go on to enjoy an acceptable quality of life for several months (and occasionally longer) following an initial episode of ATE.

Case example 3

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 13-year-old male neutered domestic short hair cat presented for acute onset bilateral pelvic limb paralysis. The cat was an indoor cat and had seemed normal when last seen by the owner several hours earlier. The owner’s attention had been drawn by the cat’s vocalization and the cat had subsequently been found recumbent next to the chair in which he had been sleeping. The cat was distressed and was thought to have fallen off the chair.

Major body system examination

Major body system examination revealed the cat to be vocalizing and distressed. Heart rate was elevated at 260 beats per min and a gallop sound was audible; a murmur could not be detected. Mucous membranes were pale pink with normal capillary refill time. The cat was tachypnoeic (respiratory rate 40 breaths per min) but lung field auscultation was appropriate for the rate and effort. Rectal temperature was reduced at 37.0°C. Abdominal palpation was unremarkable.

Femoral pulse was absent in both pelvic limbs and both paws were cold with pale digital pads. The quicks appeared purple in colour. Bilateral paralysis was present and the muscles of the right pelvic limb were swollen and severely painful on palpation. Pain sensation was absent from the left pelvic limb. An ultrasonic Doppler device for measuring blood pressure failed to detect blood flow in either pelvic limb and no active bleeding was detected when a nail in the left pelvic limb was cut back to its quick.

Clinical Tip

Case management

An intravenous catheter was placed immediately in a cephalic vein and analgesia provided (methadone 0.5 mg/kg i.v.) to alleviate the cat’s pain while the examination findings, presumptive diagnosis and prognosis were discussed with the owner. The owner was very distressed, especially given the peracute clinical deterioration without any premonitory signs, but eventually opted for euthanasia to be performed without further intervention.

Clinical Tip

Canine Pericardial Effusion

Theory refresher

Pericardial effusion is an abnormal accumulation of fluid in the pericardial sac. The haemodynamic consequences of this fluid accumulation depend on the rate of accumulation, the volume of fluid and the compliance of the pericardium. Fluid accumulation results in an increase in intrapericardial pressure that compromises ventricular filling. The right side of the heart is typically affected more than the left initially as the myocardium is thinner and intraventricular pressure is lower on the right side. The most severe clinical manifestation of this cardiac tamponade is cardiogenic shock characterized by low cardiac output failure and systemic hypotension. With more chronic effusion, signs of right-sided CHF usually predominate.

Causes

The two most common causes of canine pericardial effusion are neoplasia and idiopathic pericarditis. Intrapericardial tumours include haemangiosarcoma and heart base tumours. Echocardiographic findings may be highly suggestive of tumour type but histopathology is needed for definitive diagnosis; this is not realistic antemortem.

Haemangiosarcoma is the most commonly diagnosed canine cardiac tumour and arises most often from the wall of the right atrium or auricle. It is the most common cause of canine pericardial effusion and is assumed to have metastasized in virtually all cases at the time of diagnosis; prognosis is very poor. Surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy are offered by some referral centres.

The most common heart base tumours in dogs are aortic body tumours (chemodectomas). Mesothelioma is a diffuse neoplasm affecting serosal surfaces including the serous pericardium and does not cause obvious pericardial thickening on echocardiography. Pericardial fluid cytology is unable to differentiate effusion secondary to idiopathic pericarditis from effusion secondary to mesothelioma, and pericardial histopathology may also not be able to differentiate the two causes. Mesothelioma should therefore always be considered a differential diagnosis for presumed idiopathic pericardial effusion. Although pericardial fluid analysis is of limited benefit in most cases, cardiac lymphoma may be diagnosed in this way and is potentially responsive to chemotherapy.

Other causes of pericardial effusion include coagulation disorders, CHF, trauma, infectious causes and uraemia, although clinically significant effects with respect to tamponade are unlikely in these cases. Pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade secondary to anticoagulant rodenticide toxicity have been reported in a dog and, if facilities allow, evaluation of coagulation is recommended prior to pericardiocentesis.

Constrictive and effusive-constrictive pericarditis

In some dogs historical and clinical findings are consistent with tamponade secondary to pericardial effusion but little or no effusion is subsequently identified. A diagnosis of constrictive or effusive–constrictive pericarditis due to fibrosis should be considered in such cases.

Left atrial rupture

Left atrial rupture and consequent haemopericardium are uncommon but may occur in dogs with chronic mitral valve disease. Associated clinical signs include collapse as well as coughing and dyspnoea, and physical examination findings include a heart murmur, poor peripheral pulses and muffled heart sounds. Dogs that suffer left atrial rupture are typically much smaller than those that present with pericardial effusion of other aetiologies and the presence of an audible heart murmur is another distinguishing feature.

Only partial drainage of the pericardial effusion is recommended as thorough drainage may exacerbate bleeding. Regardless of intervention, the prognosis is very poor with this condition.

Case example 4

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 4-year-old male neutered Saint Bernard dog presented with a 2-week history of lethargy, exercise intolerance, variable appetite and progressive abdominal distension.

Clinical Tip

Major body system examination

Major body system examination revealed the dog to be anxious but ambulatory. Heart rate was elevated at 170 beats per minute and heart sounds were muffled. Peripheral pulses were weak but dorsal pedal pulses remained palpable and pulse deficits were not suspected. Mucous membranes were pale pink with a prolonged capillary refill time. Neither jugular venous distension nor pulsus paradoxus could be readily appreciated. The dog was panting continuously but lung auscultation was assessed as unremarkable. Marked abdominal distension with a palpable fluid thrill was detected.

Clinical Tip

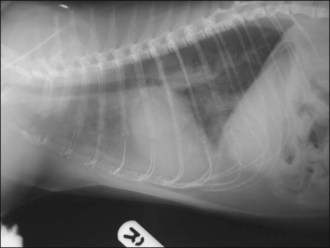

Case management

An intravenous catheter was placed into a cephalic vein and blood obtained via the catheter for an emergency database that was unremarkable. Continuous electrocardiogram monitoring was commenced and sinus tachycardia identified. Echocardiography confirmed the clinical suspicion of pericardial effusion (Figure 31.4).

Figure 31.4 Echocardiogram image of pericardial effusion visible as an anechoic space around the heart; both a collapsed right ventricle and the left ventricle are also visible.

(Photograph courtesy of Tobias Wagner)

Clinical Tip

Clinical Tip

The dog was sedated using butorphanol (0.2 mg/kg i.m.) and midazolam (0.2 mg/kg i.m.) and pericardiocentesis successfully performed (see p. 293). One litre of sanguineous pericardial fluid was removed and the dog’s cardiovascular status improved notably. Samples of the fluid were kept in appropriate containers for cytology. Ultrasonography showed only minimal residual pericardial effusion.

Clinical Tip

The dog was kept on continuous electrocardiogram monitoring for several hours but only occasional ventricular premature complexes (VPCs) were noted. Repeat ultrasonography showed no recurrence of pericardial effusion. The dog was then referred (along with the fluid samples) for further investigations that failed to reveal an underlying cause for the effusion. A presumptive diagnosis of idiopathic pericardial effusion was made.

Feline Pericardial Effusion

Pericardial effusion is much less common in cats and typically occurs as part of a generalized systemic disorder, in particular CHF. Clinical signs specifically resulting from pericardial effusion and tamponade are unusual in cats and signs are more commonly associated with concurrent pulmonary oedema or pleural effusion. Tachypnoea and other respiratory signs are reported most frequently.

To the author’s knowledge a comparable syndrome to that resulting from idiopathic pericardial effusion in dogs has not been reported in cats. Neoplasia is recognized as a cause of pericardial effusion in cats. Lymphoma is the most common feline cardiac neoplasm and usually causes pericardial effusion, cytological examination of which often provides the diagnosis. Pericardial effusion secondary to feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) has also been reported and a variety of other causes may be identified.

The procedure for pericardiocentesis in cats is similar to that in dogs. Sedation and ultrasound-guided aspiration are recommended.