22 Regurgitation

Regurgitation is the passive expulsion of oesophageal or gastric contents from the oral cavity, and is most commonly the result of oesophageal disease. Regurgitation is the most common sign of, but not pathognomonic for, oesophageal disease, and other differential diagnoses, in particular pharyngeal disorders, must be considered. There are a large number of possible causes of regurgitation; some of the more common are listed in Box 22.1. In the author’s experience, megaoesophagus and oesophageal foreign bodies are the most common reasons for regurgitation in emergency patients.

BOX 22.1 Causes of regurgitation related to the oesophagus

Clinical Tip

Table 22.1 Comparison of regurgitation and vomiting

| Regurgitation | Vomiting |

|---|---|

| No prodromal signs; signs associated with pain may mimic nausea | Prodromal signs of nausea (e.g. hypersalivation, restlessness) |

| Passive (no abdominal contractions); postural changes associated with pain possible (e.g. stretching neck) | Active with abdominal contractions |

| No consistent relationship with feeding | No consistent relationship with feeding |

| Undigested (or digested) food, or liquid; undigested food often tubular in shape | Digested food |

| No bile but may contain frothy saliva | Bile may be present |

Approach to Regurgitation

Signalment

Signalment may help to raise or lower the index of suspicion for certain differential diagnoses. Puppies with regurgitation are most likely to be suffering from congenital abnormalities, especially vascular ring anomaly (often present soon after weaning) and idiopathic megaoesophagus. Oesophageal foreign bodies are more common in smaller dogs, while some breeds (e.g. Golden Retrievers, German Shepherd dogs) are at increased risk of megaoesophagus (see below).

History

It is important to question the owner carefully for a good description of the animal’s behaviour in order to differentiate regurgitation from vomiting and even retching or gagging (see Table 22.1). Other signs consistent with oesophageal disease may also be present and include hypersalivation, pain on eating and dysphagia. A history of coughing or respiratory abnormalities may suggest aspiration pneumonia.

In addition, the animal may be exhibiting other clinical signs that will help to raise the index of suspicion for localized versus generalized causes. There may also be a history of recent general anaesthesia or drug administration, or a witnessed or suspected episode of ingestion of an irritant substance.

Major body system examination

Physical examination findings are largely dependent on the underlying cause and may be completely normal in animals with localized oesophageal disease. Respiratory examination may be abnormal in animals with aspiration pneumonia (e.g. dyspnoea, harsh lung sounds, crackles); in severe cases there may be evidence of systemic cardiovascular compromise (sepsis) and possibly pyrexia. Signs of systemic disease, in particular neuromuscular, may be present in some cases, and weight loss occurs with chronic regurgitation. Puppies with congenital abnormalities are often thin and stunted.

Emergency database

The emergency database may well be unremarkable in a number of animals with regurgitation. Manual packed cell volume and serum total solids may be consistent with dehydration in some cases. Peripheral blood smear examination may demonstrate leucocytosis consistent with inflammatory disease, including moderate to severe oesophagitis, and neutrophils may show toxic changes and band forms with aspiration pneumonia (see Ch. 3). Megaoesophagus is occasionally identified in animals with hypoadrenocorticism (Addison’s disease, see Ch. 34) and consistent abnormalities may be identified (hyponatraemia, hyperkalaemia, hypoglycaemia, azotaemia; lack of stress leucogram).

Diagnostic imaging

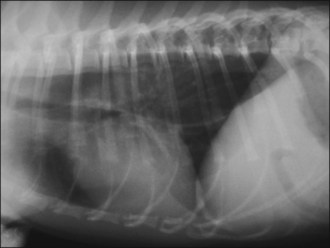

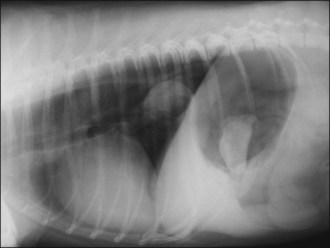

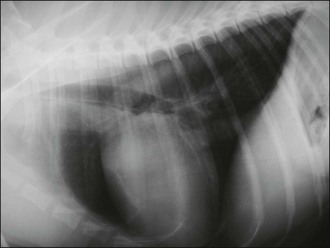

Plain thoracic radiographs (typically right lateral and dorsoventral (or left lateral) views) are useful in animals with regurgitation and may help to identify megaoesophagus, radiopaque oesophageal foreign bodies, aspiration pneumonia and mediastinal masses (Figures 22.1-22.3).

Figure 22.1 Right lateral thoracic radiograph in a dog showing megaoesophagus secondary to myasthenia gravis.

Figure 22.2 Right lateral thoracic radiograph in a dog showing a distal oesophageal foreign body (bone). Oesophageal dilation is present and a bone is also visible in the stomach.

Figure 22.3 (a) Right lateral and (b) left lateral thoracic radiographs in a dog with severe aspiration pneumonia. Multiple air bronchograms are clearly visible in the ventral lung fields.

If megaoesophagus is considered a significant possibility, radiographs should be taken without sedation or general anaesthesia. Aspiration pneumonia is most commonly identified as an alveolar pattern with air bronchograms in the right middle lung lobe and ventral parts of the other lobes, especially cranioventrally (Figure 22.3). Radiographs must not be prioritized over oxygen therapy and cardiovascular stabilization in animals with severe dyspnoea at presentation and these animals should be subjected to minimum stress.

Most oesophageal foreign bodies diagnosed in dogs are radiopaque (e.g. bones, fish hooks). Occasionally a lodged foreign body causes oesophageal perforation or rupture that may be identified radiographically as pneumomediastinum (possibly with pneumothorax) (Figure 22.4). Small volume pneumomediastinum is most often identified as gas lucency within the mediastinum that outlines the tracheal wall.

Figure 22.4 Right lateral thoracic radiograph in a dog showing air in the mediastinum highlighting the tracheal wall.

If plain radiographs do not provide a diagnosis, contrast radiography may be employed. A water-soluble contrast medium should be used in animals in which oesophageal rupture or aspiration is considered likely as the presence of barium in the lungs or mediastinum can induce marked chronic inflammation. Liquid contrast medium may delineate the oesophagus or confirm the presence of a radiolucent foreign body. A barium meal can be helpful to identify megaoesophagus or vascular ring anomalies, strictures and extraluminal compression. Barium meals should not be attempted in animals that may have compromised swallowing, either due to dysphagia or severe morbidity.

Some animals require referral for more advanced imaging, fluoroscopy in particular.

Endoscopy

Endoscopy can be extremely useful in oesophageal diseases allowing diagnosis of mural and intraluminal lesions as well as sites of extraluminal compression. It also allows therapeutic interventions, especially foreign body removal (Figure 22.5).

Treatment

Treatment of regurgitation centres on addressing the underlying disorder if possible and an extensive discussion is beyond the scope of this book. Successful management of the primary disorder may or may not resolve clinical signs of oesophageal disease, especially if severe oesophagitis is present. Treatment of oesophagitis may include administration of sucralfate and reducing gastric acidity. The latter is ideally achieved through the use of a proton pump inhibitor such as omeprazole; however, a histamine (H2) receptor antagonist (e.g. ranitidine, famotidine) may be used if omeprazole is not available.

Aspiration pneumonia

Aspiration pneumonia typically requires aggressive intervention that is tailored to the circumstances of the individual patient. Broad-spectrum antibiosis is essential and is typically given intravenously initially; subsequent enteral antibiosis may need to be continued for several weeks. Appropriate choices initially include amoxicillin/clavulanic acid or a cephalosporin; ideally this should be reassessed on the basis of culture and sensitivity results obtained from samples collected via transtracheal aspiration, tracheal wash or bronchoalveolar lavage. Fluid therapy may be required to address systemic hypoperfusion in severe cases, as well as for rehydration and maintenance purposes. The need for oxygen therapy should be decided on the basis of the severity of respiratory compromise and pulse oximetry (or arterial blood gas analysis). Regular nebulization (without coupage) and gentle exercise are also important.

Megaoesophagus

Megaoesophagus is characterized by generalized dilation of the oesophagus with lack of peristalsis. Both congenital and acquired forms are recognized. Congenital megaoesophagus is most commonly idiopathic or due to a vascular ring anomaly. Animals with vascular ring anomalies often present shortly after being weaned on to solid food, at which time the oesophageal obstruction becomes more obvious. Megaoesophagus in older animals is most commonly idiopathic but may be acquired as a secondary abnormality of a number of disorders; focal myasthenia gravis is the most common.

A number of dog breeds appear predisposed to vascular ring anomalies; for example the German Shepherd dog and the Irish Setter are predisposed to persistent right aortic arch. Vascular ring anomalies are less common in cats. A number of canine breeds are predisposed to congenital idiopathic megaoesophagus, including the Great Dane, the German Shepherd dog, the Irish Setter, the Labrador retriever and the Shar-pei. Congenital idiopathic megaoesophagus is rare in cats but the Siamese may be predisposed. Idiopathic megaoesophagus in adult dogs is seen more commonly in certain breeds, including the golden retriever and the German shepherd dog.

Megaoesophagus is usually readily diagnosed by plain radiography although occasionally a contrast study may be required (see Figure 22.1). The dilated oesophagus may be filled with air, fluid or ingesta. As described above, aspiration pneumonia is the most common complication of megaoesophagus and may be detected radiographically. Once the diagnosis is made, additional tests are indicated to screen for a primary underlying cause.

Treatment of megaoesophagus centres on addressing an underlying cause if one is identified. Animals with idiopathic megaoesophagus or in which megaoesophagus does not resolve despite treatment of the underlying disorder require long-term symptomatic and supportive care. Controlled feeding is often the mainstay of management and usually involves feeding small frequent meals (e.g. four to six meals per day) of a high calorie diet from a height and then maintaining the animal in an erect posture for 10–15 minutes if possible. It is noteworthy that some animals do better with food moulded into balls while gruel works better in others; dietary consistency must therefore be tailored to the individual patient. Treatment of aspiration pneumonia may be required as described above and in some animals long-term feeding via gastrostomy tube may be the only option.

Oesophageal Foreign Bodies

A variety of objects may become lodged in the oesophagus. Bones (especially lamb and chicken) are undoubtedly the most common culprits but others include fishing hooks, balls, toys and dental chews.

Signalment

Oesophageal foreign bodies appear to be a more common problem in certain dog breeds and the majority of affected dogs are small. In the author’s experience in the United Kingdom, terriers appear at increased risk and in particular the West Highland White terrier. Oesophageal foreign body obstruction is rare in cats. Most dogs with oesophageal foreign body obstruction are young to middle-aged.

History

In the author’s experience, in most cases there is a reported history of the dog either having been fed or having scavenged a foreign body. However, not all cases present acutely and clinical signs may have been present for several days or even 2–3 weeks before dogs are presented. Sometimes it is only following diagnosis that owners remember the exact episode when the foreign body was ingested.

Clinical signs of oesophageal foreign body obstruction include regurgitation or vomiting, retching, gagging and hypersalivation. Dogs may be anorexic, may approach the food and then turn away, or may attempt to eat with subsequent pain on swallowing and/or dysphagia. Repeated gulping or swallowing, restlessness, distress, coughing and increased respiratory effort may also be reported.

Major body system examination, emergency database

Physical examination and the emergency database may be unremarkable in dogs with oesophageal foreign body obstruction. In some cases there is evidence of nonspecific pain on examination and the author has also occasionally identified respiratory abnormalities. Very occasionally it is possible to palpate foreign bodies lodged in the cervical oesophagus from the outside. Fishing line may be identified trapped around the tongue base in dogs that have ingested a fishing hook. Dehydration may be identified on examination and emergency database.

Diagnostic imaging

In the author’s experience, the vast majority of oesophageal foreign bodies are radiopaque enough to be detected on plain radiographs; however, occasionally contrast radiography or endoscopy is required. The most common site of foreign body entrapment is the caudal oesophagus between the heart base and the cardiac sphincter (see Figure 22.2). In addition to the foreign body itself, plain radiographs often demonstrate increased soft tissue density around the foreign body and air in the oesophagus.

Plain radiographs are also useful to exclude pneumomediastinum (and possible pneumothorax) as a result of oesophageal rupture, and to identify evidence of aspiration pneumonia.

Treatment

Clinical Tip

Oesophageal foreign body obstruction should be treated as an emergency and removal should be undertaken as soon as any initial stabilization that may be required has been performed. On-going obstruction is associated with an increased risk of oesophageal rupture, stricture formation and aspiration pneumonia. Damage to the wall of the oesophagus depends on the type, size and sharpness of the foreign body, and the duration of obstruction. If facilities or expertise are not available to perform removal in-house, immediate referral should be arranged. It is essential to ensure that animals that have been anaesthetized for radiography are adequately recovered before being transported.

Treatment of oesophageal foreign body obstruction involves removal of the foreign body from the oesophagus. The author uses flexible endoscopy for this purpose but some clinicians prefer to use fluoroscopic guidance. The foreign body is removed orally, typically using large rigid grasping forceps but occasionally other types of forceps are required. The oesophageal mucosa is evaluated at the time of removal for the severity of injury that will both help to guide the length of any subsequent medical therapy and potentially inform on the risk of possible stricture formation.

Clinical Tip

Occasionally it is not possible to remove the foreign body orally, even in little pieces, and it has to be pushed into the stomach. Many foreign objects will then either dissolve over time or go on to be passed in the faeces; occasionally, however, surgical removal via gastrotomy is required. Very occasionally oesophagotomy (or gastrotomy for very distal oesophageal foreign bodies) is required as the foreign body cannot be dislodged in either direction; however, in the author’s experience, this is rare.

The author typically takes plain radiographs following removal to check for the presence of pneumomediastinum suggestive of oesophageal rupture during removal. If there is any doubt, a positive contrast oesophagram using water-soluble contrast medium may be helpful although interpretation may be difficult. Surgical repair via thoracotomy is traditionally required if rupture occurs given the risks of mediastinitis and pleuritis. However, if financial constraints preclude this intervention, some dogs may recover fully with prolonged antibiosis; prognosis for recovery is likely to be related to the extent of leakage.

Management following removal is guided by the findings in each individual case. In some cases, no additional medical therapy is required and the dogs can be discharged once they have fully recovered from the procedure and demonstrated an interest in food. In other cases, hospitalization for on-going analgesia (typically buprenorphine) and intravenous fluid therapy may be indicated for 24–48 hr. Medical therapy for oesophageal mucosal injury and oesophagitis may include sucralfate, omeprazole and/or a histamine (H2) receptor antagonist, with the extent and duration of treatment depending on the individual case. Occasionally some dogs continue to regurgitate for several days following removal due to moderate-to-severe oesophagitis necessitating lengthier hospitalization.

The author typically recommends feeding of a soft food for a few days following discharge. Owners should be warned of the possibility of stricture formation that may lead to recurrence of clinical signs of oesophageal disease 1–4 weeks later.