28 The trauma patient

Trauma is one of the most common reasons for emergency presentation and can also be one of the most stressful to the patient, owner and veterinary personnel. A calm and rational approach is therefore paramount. Trauma is especially common in cats, amongst which motor vehicle accidents (road traffic accidents) are very common, and more so than dogs, severely injured cats can decompensate very easily without appropriate management. The majority of this chapter therefore focuses on cats although most of the principles and information provided are equally applicable to dogs.

The most common causes of trauma in companion animals are motor vehicle accidents, animal (especially dog) bite injuries, tail pull injuries and falls from a height (especially feline high-rise syndrome). Puppies and kittens are also relatively commonly trodden on and dogs may be kicked by horses. The most common injuries that occur following motor vehicle accidents are listed in Box 28.1. Cranial, thoracic and pelvic injuries are especially common in cats.

Traumatic Brain Injury

Theory refresher

Minimizing secondary brain injury

The prime aim in the management of traumatic brain injury (TBI) is to limit secondary brain injury that may occur as a result of various mechanisms including hypoxia, ischaemia due to hypoperfusion, raised intracranial pressure (ICP) or active haemorrhage. Earlier discussions of TBI tended to focus on the detrimental effects of raised ICP via impairment of cerebral blood flow and the potential for brainstem compression and herniation. However, secondary brain injury is significantly perpetuated by hypoxia and systemic hypoperfusion, and the priority is therefore to ensure that the brain receives an adequate supply of well-oxygenated arterial blood. Treatment for possible raised ICP is just one part of this therapy.

Ensuring adequate oxygenation and ventilation

Hypoxia must be avoided at all costs and pulse oximetry (and arterial blood gas analysis if available) should be used. A percentage saturation of haemoglobin with oxygen (SpO2) on room air of more than 95% is satisfactory. Animals with low SpO2 should be provided with oxygen supplementation immediately and a liberal ‘if in doubt, supplement oxygen’ approach is strongly encouraged. In addition, any processes that may interfere with adequate ventilation (e.g. pneumothorax, pain) must be addressed appropriately.

Ensuring adequate cerebral perfusion

Cerebral blood flow, and hence oxygen and nutrient delivery to the brain, is driven by the cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) gradient between mean arterial pressure (MAP) and ICP:

Normal homeostatic mechanisms protecting cerebral blood flow may be lost in TBI and cerebral blood flow becomes largely dependent on systemic blood pressure. Maintenance of an adequate CPP is a cornerstone of modern brain injury therapy.

Mean arterial pressure

The head trauma patient may well present with systemic hypotension (i.e. decreased MAP). Mean arterial pressure can be measured noninvasively using an oscillometric device and a reasonable target MAP is 80 mmHg. If only Doppler sphygmomanometry is available, then a systolic blood pressure of 100 mmHg is considered equivalent.

Raised intracranial pressure

ICP is the pressure exerted between the skull and the three intracranial compartments – brain parenchyma, blood and cerebrospinal fluid. Direct measurement of ICP is not practical in veterinary medicine at this time and the presence of elevated ICP is therefore inferred. The Cushing response is the most specific marker available – intracranial hypertension causes systemic hypertension and a consequent reflex bradycardia. These findings should prompt aggressive treatment for raised ICP. Other less specific findings that may suggest intracranial hypertension include otherwise unexplained deterioration of mental status, dilated nonresponsive pupils, loss of physiological nystagmus and decerebrate posturing.

Neurological examination

Once potentially life-threatening extracranial abnormalities have been addressed, a thorough baseline neurological examination should be performed.

Treatment

Treatment of TBI is summarized in Table 28.1 and illustrated further in Case example 1.

Table 28.1 Treatment of traumatic brain injury

ICP, intracranial pressure; SpO2, percentage saturation of haemoglobin with oxygen.

Prognosis

Some clinicians use a Modified Glasgow Coma Scale (The Small Animal Coma Scale) as a quantitative way of grading and monitoring brain injury and assisting with prognosis. Ultimately, signs of slow but steady improvement on repeat neurological evaluation may be the most practical guide.

Nursing Aspect

Patients with traumatic brain injury may be recumbent for prolonged periods and the value of adequate nursing in such cases should not be underestimated. The most important measures are as follows:

Case example 1

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 3-year-old male neutered domestic long hair cat presented shortly after a presumed motor vehicle accident. The cat had been healthy prior to going out that evening but had returned home some time later in respiratory distress. Notable deterioration had occurred in the time it had taken the owners to bring the cat to the clinic. No other significant preceding history was reported.

Major body system examination

On presentation the cat was stuporous. Heart rate was 160 beats per minute with no murmur or gallop sound heard and femoral pulses could not be palpated. Mucous membranes were pale pink with a prolonged capillary refill time and extremities were cold. The cat was tachypnoeic but lung sounds were appropriate for the rate and effort. Percentage saturation of haemoglobin with oxygen (SpO2) on room air was 97%. Abdominal palpation was unremarkable but the cat was mildly hypothermic (rectal temperature 36.5°C). There were palpable skull fractures in the region of the left frontal bone and left-sided scleral and nasal haemorrhage was identified. Blood pressure could not be obtained initially by sphygmomanometry.

Assessment

The cat was assessed as moderately to severely hypovolaemic and the presence of hypothermia was not considered unusual in a cat with this presentation. Although the cat’s mental status could in part be attributed to the hypovolaemia, it was felt to be too severely altered and, given the clear evidence of head injury, a component of TBI was therefore suspected. The cat’s respiratory status seemed appropriate and neither significant intrathoracic injury nor a central effect on respiration was suspected. At this stage it was not possible to make a reliable assessment of the cat’s pain status.

Emergency database

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and blood obtained via the catheter for an emergency database. This revealed low–normal manual packed cell volume (PCV) (32%, reference range 31–45%) with low serum total solids (TS) (50 g/l, reference range 61–80 g/l) suggestive of recent haemorrhage. The cat was moderately hyperglycaemic (15.0 mmol/l, reference range 4.2–6.6 mmol/l).

Clinical Tip

Case management

Clinical Tip

Hypertonic saline was not available and a 20 ml/kg bolus of 0.9% sodium chloride (normal, physiological saline) was therefore administered intravenously over 15 minutes. No warming measures were implemented at this time and the cat was kept in sternal recumbency with his head elevated at a 30° angle to the table. A more thorough baseline neurological evaluation was performed at this time. Anisocoria was present with the right pupil larger than the left but a menace response could not be elicited in either eye. Bilateral pupillary light responses, both direct and consensual, were intact. Blink and gag reflexes were present and jaw tone was adequate. The cat’s posture seemed appropriate. Oculocephalic reflex was not tested at this time.

A low dose (0.1 mg/kg slow i.v.) of methadone was administered during the initial fluid bolus. At the end of the bolus the cat’s perfusion had improved but he remained mildly hypovolaemic. A further conservative bolus of 5 ml/kg was administered over 10 minutes, after which the cat was assessed as euvolaemic.

Despite the improved perfusion, the cat’s mentation remained inappropriately reduced and it was therefore suspected that this was the result of raised intracranial pressure secondary to traumatic brain injury. Mannitol (0.5 g/kg i.v. bolus over 20 minutes) was therefore administered, following which a slow but notable clinical improvement was detected. The anisocoria resolved and the cat was able to raise his head voluntarily. Systolic blood pressure at this time was within normal limits (105 mmHg). No free peritoneal fluid was detected on abdominal ultrasound. Thoracic radiographs were not taken because it was felt that the index of suspicion for significant intrathoracic injury was too low to justify the additional stress involved for the cat.

Clinical Tip

Animals with traumatic brain injury must be monitored very closely, in particular for the following three developments.

Clinical Tip

The cat was maintained on intravenous fluid therapy and analgesia (buprenorphine 0.02 mg/kg i.v. q 6 hr), and monitored closely including repeat neurological examinations. He improved steadily with respect to his neurological status and, although not further investigated, the skull fractures were therefore not suspected to be surgical in nature.

However, the cat remained anorexic and an oesophagostomy tube was therefore placed under general anaesthesia 3 days after initial presentation. The cat made an uneventful recovery from this procedure and was subsequently discharged. His owner was asked to tempt him to eat but to feed him via the oesophagostomy tube regardless until he was eating satisfactorily on his own. Meloxicam oral suspension was dispensed, to be administered via the feeding tube initially.

Clinical Tip

Thoracic Injury

Theory refresher

Thoracic injuries following blunt trauma include:

In the author’s experience, pneumothorax and pulmonary contusions are the most common.

Pneumothorax

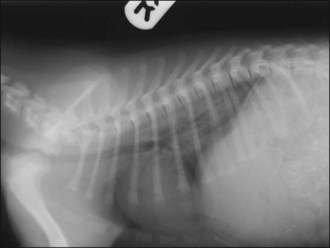

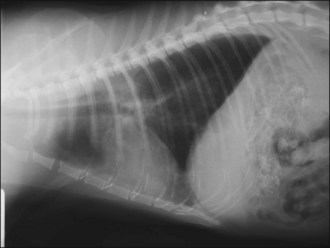

Closed pneumothorax usually results from leakage of air secondary to a lesion within the lung parenchyma, although it may also occur for example due to damage to the airways or oesophagus (Figure 28.2). Open pneumothorax involves loss of integrity of the thoracic wall (e.g. following penetrating trauma) while a tension pneumothorax occurs if a one-way valve is formed at the site of air leakage such that air taken in during inspiration leaks into the pleural space but cannot be expelled (Figure 28.3). The result is a rapid and potentially life-threatening increase in intrapleural pressure with severe respiratory and cardiovascular compromise and immediate thoracocentesis is required. In the author’s experience tension pneumothorax is rare.

Figure 28.2 (a) Right lateral and (b) dorsoventral thoracic radiographs of a cat showing pneumothorax and pulmonary contusions following trauma.

Figure 28.3 Right lateral thoracic radiograph of a dog showing traumatic tension pneumothorax. The dog underwent cardiopulmonary arrest just prior to arrival at the hospital and the owner did not want resuscitation to be attempted.

Thoracocentesis is by no means required in all cases of traumatic closed pneumothorax and the air will be resorbed over days to weeks. The decision to perform thoracocentesis should be guided by whether the pneumothorax is thought to be compromising respiration in a clinically significant way. Clinical improvement following thoracocentesis is generally associated with aspiration of 20–30 ml/kg or more of air although improvement may be noted with removal of smaller volumes in animals with other concomitant thoracic injuries, most commonly pulmonary contusions. In the author’s experience thoracocentesis does not usually need to be performed more than twice for traumatic pneumothorax and chest drain placement is infrequently indicated. The need for surgical intervention is rare.

As well as occurring as a result of trauma, pneumothorax may also be spontaneous following rupture of pulmonary lesions (e.g. bullae, tumours, subpleural blebs) or iatrogenic (e.g. following thoracocentesis or fine needle lung aspiration). Pneumothorax that occurs spontaneously is often more severe than following trauma, and chest drain placement and surgical intervention are more likely to be indicated.

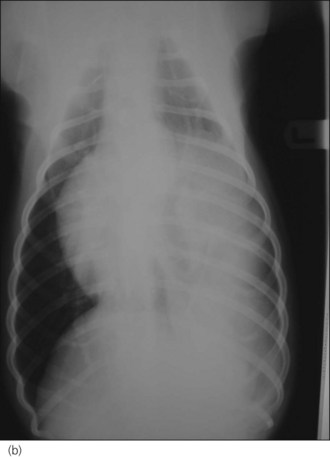

Pulmonary contusions

Pulmonary contusions represent areas of alveolar and interstitial haemorrhage and oedema, and probably represent the most common thoracic injury in dogs and cats following trauma. Not all affected animals develop associated clinical signs and pulmonary contusions may occur with or without other thoracic injuries. Clinical signs may develop acutely or over several hours, and radiographic changes may lag behind clinical signs by up to 24 hours. Radiographic abnormalities (patchy or diffuse alveolar or interstitial lung changes) may persist for a variable period of time despite clinical improvement (Figure 28.4). There is no specific treatment for pulmonary contusions and management typically involves oxygen supplementation, cage rest, analgesia as indicated for concurrent injuries, minimal stress and time.

Intravenous fluid therapy does not have to be withheld but caution is advised. Hypovolaemia is common in patients with pulmonary contusions at time of presentation and the aim of fluid therapy should be to restore acceptable tissue perfusion while avoiding excessive fluid administration. It may be acceptable in some cases to leave the patient mildly hypovolaemic rather than risk worsening pulmonary contusions. Diuretics are not recommended in the treatment of pulmonary contusions and are contraindicated in hypovolaemia.

The incidence of bacterial pneumonia following pulmonary contusions is very low and the indiscriminate use of antibiotics in these cases is not recommended.

Clinical Tip

Haemothorax

Haemothorax is accumulation of blood in the pleural space. It is not uncommon to detect a small volume of pleural effusion following blunt thoracic trauma that is presumed to be secondary to haemorrhage. However, in the author’s experience, clinically significant haemothorax is relatively rare. The pleural space can accommodate a considerable volume of blood without causing clinically significant respiratory compromise and haemothorax should not be drained unless it is thought to be significantly contributing to dyspnoea; the blood will be resorbed over several days. This is especially important as anaemia secondary to haemorrhage is relatively common following trauma, particularly in cats.

If haemothorax is drained, it is sensible to remove as small a volume (e.g. 20 ml/kg) as possible that is expected to allow clinical improvement in respiratory status (i.e. so that the remainder may be resorbed). Surgical intervention for traumatic haemothorax is seldom required.

Aside from trauma, haemothorax may also occur as a result of severe coagulopathy, in particular due to anticoagulant rodenticide intoxication; other less common causes are neoplasia, pulmonary thromboembolism, lung lobe torsion and iatrogenic causes.

Rib fractures and flail segment

It is very unusual for rib fractures to occur in dogs and cats without at least one other significant thoracic injury. Rib fractures are often only diagnosed radiographically and they typically do not require specific intervention. Rib fractures are, however, reported to be very painful and a liberal approach to analgesia is therefore recommended in these cases. Ventilation may be compromised in painful animals, especially if rib fractures are present.

A flail segment may be created if two or more adjacent ribs are fractured both dorsally and ventrally, i.e. so that the segment is no longer stabilized by attachment to the sternum or spine. This flail segment then moves paradoxically in relation to the rest of the chest wall during respiration, i.e. the flail segment moves in on inspiration and out on expiration. Although large flail segments may cause hypoventilation, flail segments typically do not contribute significantly to dyspnoea and stabilization is not usually indicated. Their significance lies more in the fact that they are typically associated with other significant thoracic injuries, especially pulmonary contusions, and that they are often very painful. These factors are more likely to be responsible for any respiratory compromise identified.

Case example 2

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 3-year-old male neutered domestic short hair cat presented shortly after a presumed motor vehicle accident. The cat had been seen sitting in the front lawn by his owner 1 hour prior to dragging himself through the cat flap. The cat was vocalizing and had increased respiratory effort. His owner reported limited movement in the left pelvic limb and tail but no movement in the right pelvic limb. No other significant history was reported.

Major body system examination

The cat was initially briefly observed in his carrier. He was depressed with an obvious increase in respiratory effort and had bilaterally symmetrical mid-sized pupils. The front half was in sternal recumbency. The top of the transport carrier in this case could be removed and the rest of the initial assessment was therefore performed with the cat remaining in his carrier. Flow-by oxygen supplementation was commenced. Heart rate was 220 beats per minute with no murmur or gallop sound heard and the dorsal pedal pulse could just be palpated.

Mucous membranes were pink with a normal capillary refill time. Respiratory rate was 42 breaths per minute with a marked increase in effort and lung sounds were dull dorsally. Lung sounds were possibly harsher cranioventrally than would be expected for the respiratory rate and effort but this was difficult to assess at this stage. The cat moved his left pelvic limb and tail during this initial examination but no deep pain perception or withdrawal reflex was elicited from the right pelvic limb. No further examination was performed at this time.

Assessment

Examination of the respiratory system in this case was highly suggestive of pneumothorax. The possible increase in harshness in the cranioventral lung field was potentially suggestive of pulmonary contusions that often accompany traumatic pneumothorax. As the dorsal pedal pulse could be palpated, the cat was not thought to be any more than mildly hypovolaemic and given the concern regarding pulmonary contusions, it was decided that intravenous fluid resuscitation was not a priority at this stage.

Clinical Tip

Case management

Methadone (0.3 mg/kg i.m.) was administered and the cat was placed in an oxygen cage. While in the oxygen cage the cat was observed to urinate voluntarily, voiding a moderate amount of grossly haematuric urine. Preparation was made to perform thoracocentesis and this was then undertaken successfully (see p. 291). One hundred millilitres (approximately equivalent to 20 ml/kg) of air was aspirated from the right-hand side. Although the cat remained dyspnoeic, a significant improvement in respiratory status was observed and lung sounds were audible dorsally. It was therefore decided not to perform repeat thoracocentesis on the other side at this time. The previous suspicion of harsh lung sounds was confirmed, supporting the likelihood of pulmonary contusions.

As the cat remained compliant, further examination and interventions were performed at this time with flow-by oxygen supplementation provided throughout. Abdominal palpation was uncomfortable but no free fluid was detected ultrasonographically. The pelvis was painful on gentle palpation but there was good anal tone and perineal reflex.

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and blood obtained via the catheter for an emergency database that was unremarkable. The cat was returned to the oxygen cage and analgesia in the form of intermittent boluses of methadone (0.2 mg/kg i.v. q 4 hr) continued. It was envisaged that the cat would be anorexic but given the likelihood of pulmonary contusions, only maintenance intravenous isotonic crystalloid therapy (compound sodium lactate at 2 ml/kg/hr) was administered.

Forty-eight hours after initial presentation the cat’s respiratory status had improved satisfactorily and he had been weaned off oxygen supplementation. General anaesthesia was performed and pelvic radiography confirmed multiple fractures with medial displacement of the caudal right hemipelvis, resulting in significant narrowing of the pelvic diameter. The fractures were therefore assessed as surgical in nature and the cat was referred for specialist repair and oesophagostomy tube placement.

Traumatic Diaphragmatic Rupture

Theory refresher

Although listed here as a thoracic injury, acquired diaphragmatic rupture typically occurs as a result of blunt abdominal trauma. Circumferential and right-sided diaphragmatic tears are most common in dogs and cats and the liver is reportedly the most commonly herniated organ. In addition, the stomach, small intestine and spleen are often involved in left-sided hernias and the small intestine and pancreas in right-sided hernias.

Diagnosis

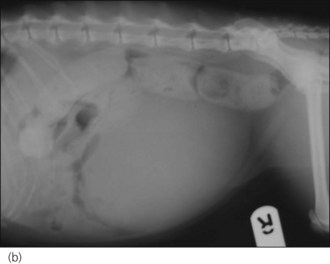

Radiography is commonly used in animals with suspected diaphragmatic rupture and consistent findings include complete or partial loss of the diaphragmatic line, mediastinal shift, obscuring of the cardiac silhouette, and cranial displacement of abdominal viscera and gas shadows (Figures 28.5 and 28.6). Orthogonal views are recommended but diagnosis may be difficult, for example if displaced viscera are obscured by pleural fluid or in the absence of visceral displacement. Positive contrast gastrography or peritoneography may be required in these cases.

Figure 28.5 (a) Right lateral and (b) dorsoventral thoracic radiographs of a cat showing diaphragmatic rupture.

Figure 28.6 (a) Right lateral and (b) dorsoventral thoracic radiographs of a cross-bred dog showing diaphragmatic rupture.

If facilities and expertise allow, ultrasonography provides an alternative, reliable and less stressful means of diagnosing diaphragmatic rupture. This may be especially helpful earlier on in unstable patients or in those with significant pleural effusion obscuring radiographic detail.

Timing of surgical intervention

The timing of surgical intervention for diaphragmatic rupture has been the subject of some debate, with many authors recommending a delay of more than 24 hours following trauma to ensure adequate time for stabilization of other concurrent conditions (e.g. hypovolaemic shock) and injuries (e.g. pulmonary contusions), thereby reducing the risks associated with general anaesthesia and major surgery. However, current literature suggests that surgical intervention within 24 hours of admission in stable patients does not worsen the prognosis and therefore timing of surgical intervention should be made on an individual case basis.

Clinical Tip

Case example 3

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 5-year-old female entire Yorkshire terrier presented a short time after a witnessed motor vehicle accident. The dog had remained conscious and ambulatory following the incident but she was noted to have some increased respiratory effort by her owner, prompting emergency presentation. No other significant history was reported.

Major body system examination

On presentation the dog was quiet and responsive although she had an unpredictable temperament, attempting to nip intermittently during examination. Cardiovascular examination revealed a heart rate of 212 beats per minute. Heart sounds could not be heard on the left side of the thorax but were readily audible in the right hemithorax. Peripheral pulses were hyperdynamic and ocular mucous membranes were pink; capillary refill time was not assessed. Respiratory rate was 48 breaths per minute with an increase in effort. Lung sounds were significantly decreased on the left side but were readily audible and diffusely harsh in the right hemithorax. No further examination was performed at this time.

Clinical Tip

Although respiratory dysfunction is a common presenting sign of traumatic diaphragmatic rupture, it may be minimal or even absent in a number of cases. The aetiology of respiratory compromise is usually multifactorial and may include:

In some animals with diaphragmatic rupture acute respiratory decompensation may occur as a result of accumulation of a significant volume of abdominal viscera in the pleural space. In such cases, holding the animal upright to allow the abdominal contents to return to the peritoneal cavity is potentially life-saving.

Assessment

The findings on thoracic auscultation in this case were suggestive of possible diaphragmatic rupture with displacement of intra-abdominal contents predominantly into the left hemithorax. The harsh lung sounds audible on the right were likely due to pulmonary contusions. Cardiovascular examination may have suggested mild hypovolaemia; however, pain, anxiety and signalment were also thought to be contributing to the tachycardia. Given the concerns regarding pulmonary contusions, it was not felt that volume resuscitation was indicated at the outset.

Case management

Methadone (0.5 mg/kg i.m.) was administered. The fur over both cephalic veins was clipped and EMLA® cream 5% (AstraZeneca, see Ch. 5) applied topically. The sites were covered with an occlusive dressing and the dog was placed in an oxygen cage and monitored closely for 30 minutes. By the end of this time the dog’s heart rate had reduced considerably and her temperament had also notably improved. Respiratory rate had reduced but there had been no notable change in effort.

An intravenous catheter was placed in one of the cephalic veins and blood obtained via the catheter for an emergency database that was unremarkable. Brief ultrasonography was suggestive of a loss of diaphragmatic integrity with displacement of at least the stomach into the left hemithorax. A small volume of pleural fluid was detected in the right hemithorax. A moderately sized urinary bladder was identified with no peritoneal fluid.

The dog was started on replacement isotonic crystalloid at 2 ml/kg/hr and returned to the oxygen cage. She was positioned on an incline and analgesia was continued in the form of intermittent boluses of methadone (0.2–0.3 mg/kg i.v. q 4 hr).

Thoracic radiography performed approximately 16 hours following presentation confirmed the presence of diaphragmatic rupture with probable displacement of the stomach into the left hemithorax. Midline exploratory coeliotomy and repair of the diaphragm was performed, with intermittent positive pressure ventilation (IPPV) provided as necessary, and the dog went on to make an uneventful recovery.

Clinical Tip

Pelvic Fractures

Clinical Tip

As with all emergency patients, evaluation of an animal with a suspected pelvic fracture should begin with a major body system examination and initial stabilization should be provided as needed. Priority must be given to the identification and management of potentially life-threatening extrapelvic injuries. Radiographic evaluation of the pelvis must only be done once the patient has received adequate stabilization, including the provision of suitable analgesia.

With respect to suspected lumbosacral or pelvic injury, it is important to find out whether the animal has been seen to walk and whether voluntary urination or defecation has occurred since the incident. Both pelvic limbs should be assessed for deep pain sensation and positive withdrawal reflex as a minimum. Anal tone and perineal reflex should be noted and the tail should be assessed for deep pain sensation and voluntary movement. Digital rectal examination performed at the appropriate time may provide information regarding both the degree of displacement of pelvic fractures and the width of the pelvic canal.

Pelvic fractures in cats most often involve the pelvic floor but sacroiliac luxation (potentially bilateral) and ilial body fractures are also common. A detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this book but not all pelvic fractures require surgical intervention. Conservative management may be appropriate in a proportion of cases and is more likely to be suitable for cats and small dogs than larger dogs. Surgical intervention is generally indicated in any animal in which there is, for example, significant narrowing of the pelvic canal, marked pain, neurological deficits or acetabular involvement.

Pelvic injury may be associated with damage to the lumbosacral plexus and/or the sciatic nerve. Sciatic nerve damage may manifest as severe pelvic limb paresis as well as loss of limb sensation to all but the medial aspect (supplied by the saphenous branch of the femoral nerve) including the medial digit. Lack of deep pain sensation in the other digits indicates severe sciatic nerve injury and a poor prognosis for recovery. Signs associated with damage to the pudendal, pelvic or caudal nerves may range from an inability to empty the bladder fully to complete loss of anal tone, voluntary urination, and perineal sensation (see Sacro-caudal and tail pull injuries).

Sacro-caudal and Tail Pull Injuries

The sacro-caudal region of the vertebral column contains the peripheral nerve roots of the cauda equina rather than the spinal cord. Injury to the sacral and caudal (coccygeal) nerve roots most commonly occurs as a result of sacro-caudal fractures or luxations/subluxations secondary to motor vehicle accidents and bite wounds (Figure 28.7a). Distraction and possible avulsion of the nerve roots may also occur as a result of a tail pull injury. Complete or partial, reversible or irreversible neurological dysfunction may occur depending on the extent of the injury to the nerve roots.

Figure 28.7 Right lateral radiographs showing (a) sacro-caudal subluxation and (b) large distended bladder and faecal retention in a cat.

The sacral spinal cord segments (S1 to S3) and nerve roots contribute to the pelvic and pudendal nerves (Box 28.3). Neurons from the S1 segment also contribute to the sciatic nerve. The caudal spinal cord segments provide sensory and motor innervation to the tail via the caudal (coccygeal) nerves.

Sacrocaudal and tail pull injuries are identified most commonly in cats and clinical findings may include:

Prognosis

The prognosis for cats in which only the tail is affected is very good, including possible return of tail function. Thereafter the prognosis is generally associated with the severity of neurological injury and the most severely affected animals (dilated anus with no anal tone; absent tail sensation and motor function) may not recover. Recovery, in particular with respect to tail sensation and motor function, can take weeks to months to occur. As a guideline, most cats that do not recover urinary control after 4 weeks are likely to remain incontinent. A discussion of appropriate management for animals with prolonged recovery is beyond the scope of this book.

Bite Wounds

Theory refresher

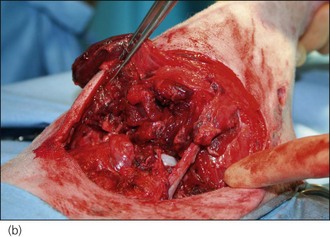

Although skin lacerations or puncture wounds may be the most visible result of a bite injury, these lesions should be considered as only the ‘tip of the iceberg’. Crushing, shearing, tearing and avulsion may occur during biting and may cause extensive and deep tissue trauma (Figures 28.8-28.11) that may not be readily appreciable from the outside. It is therefore recommended that all but the mildest of bite wounds are explored – but only at the appropriate time following extensive patient stabilization. Diagnostic imaging should be performed as indicated by the location of the wounds and positive contrast sinography may be useful in determining whether wounds have penetrated into body cavities.

Figure 28.8 (a) A West Highland White terrier that had suffered dog bite wounds to the caudal abdominal, left inguinal and proximal left pelvic limb areas. (b) Traumatic limb amputation and (c) a puncture wound in the urinary bladder are evident.

(Photographs courtesy of Zoe Halfacree)

Figure 28.9 Severe perineal and bilateral pelvic limb swelling and bruising in a cat with dog bite wounds.

(Photograph courtesy of Zoe Halfacree)

Figure 28.10 Deep penetrating dog bite wound to the flank of a dog.

(Photograph courtesy of Stephen Baines)

Figure 28.11 Extensive trauma to the thoracic limb of a dog following a dog attack.

(Photograph courtesy of Stephen Baines)

Bite wounds, whether open or closed, are invariably contaminated with bacteria. Bacteria may be inoculated deeply into traumatized tissue, with dead space and serum accumulation creating a highly suitable environment for severe infection to develop. All but the most superficial bite wounds should therefore be lavaged thoroughly and adequate drainage ensured. Primary closure of bite wounds without adequate drainage may result in disastrous consequences with respect to wound dehiscence, tissue devitalization and the development of sepsis (Figure 28.12).

Figure 28.12 Tissue devitalization and wound dehiscence in two dogs in which dog bite wounds had been closed primarily without ensuring adequate drainage.

(Photograph (a) courtesy of Zoe Halfacree; Photograph (b) courtesy of Chiara Valtolina)

Systemic antibiosis may not be required in mild low-risk bite injuries but should be provided parenterally (typically intravenously) and then orally in other cases. A broad-spectrum bactericidal antibiotic with activity against the most commonly cultured bacteria (Staphylococcus species, Escherichia coli, Enterococcus species) should be chosen. Amoxicillin/clavulanate is a good first choice. It must be remembered that antibiotics are not a substitute for appropriate lavage, debridement and drainage. Wound culture is recommended to guide further antimicrobial choice in bite wounds that become infected despite antibiosis.

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), sepsis and death may result from multiple or severe bite wounds, especially when not managed appropriately in a timely fashion.

Case example 4

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 1-year-old male neutered domestic short hair cat presented shortly after a presumed dog attack. The owners had been awoken by the cat’s howling from outside the house and had gone out to find the cat cowering under a car with a Staffordshire bull terrier dog nearby. The owners had chased the dog away and then retrieved the cat from under the car. No other significant preceding history was reported.

Major body system examination

On presentation the cat was distressed but responsive. Heart rate was 240 beats per minute and no murmur or gallop sound could be heard. Femoral pulses were hyperdynamic, mucous membranes were pink, and capillary refill time was approximately 1.5 seconds. The cat was tachypnoeic (respiratory rate 60 breaths per minute with shallow pattern) but lung auscultation was appropriate for the rate and effort. Abdominal palpation was unremarkable and the bladder was palpable and small. The cat was mildly hypothermic (rectal temperature 37.0°C).

Multiple puncture wounds were identified caudally over the dorsal pelvis and right thigh. There was severe bruising and swelling associated with these areas. Voluntary movement and pain sensation were present in both pelvic limbs and in the tail, and there was good anal tone.

Assessment

The tachycardia in this case was thought to be due to a combination of mild hypovolaemia, pain and anxiety. The cat’s respiratory status was thought to reflect these abnormalities as opposed to a primary respiratory disorder and trauma appeared to be restricted to the caudal part of the body.

Emergency database

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and blood obtained via the catheter for an emergency database. This was consistent with haemoconcentration (packed cell volume 48%, reference range 31–45%) but total solids were potentially inappropriately low (65 g/l, reference range 61–80 g/l). The cat was also moderately hyperglycaemic (13.8 mmol/l, reference range 4.2–6.6 mmol/l).

Case management

A 10 ml/kg bolus of an isotonic replacement crystalloid solution was administered over 15 minutes and analgesia provided in the form of methadone (0.4 mg/kg i.v.). The cat was also started on intravenous amoxicillin/clavulanate (20 mg/kg i.v. q 8 hr) and a brief abdominal ultrasound was performed that revealed no detectable peritoneal fluid. Cardiovascular status improved after a single bolus and the cat was subsequently maintained on the same intravenous fluid at 4 ml/kg/hr.

The cat responded well to stabilization and approximately 4 hours following initial presentation underwent general anaesthesia. Systolic blood pressure obtained via Doppler sphygmomanometry prior to induction was normal (130 mmHg). Thoracic and abdominal radiography was performed and found to be unremarkable. In particular there was no evidence of pneumoperitoneum or pneumoretroperitoneum that was of concern given the location of the puncture wounds. The cat’s pelvis was manipulated thoroughly and no significant abnormalities were detected.

All of the puncture wounds were lavaged with copious amounts of sterile normal saline. The wounds were variously explored, debrided and closed as appropriate, with a Penrose drain being placed strategically to maximize drainage. The cat recovered well from general anaesthesia and was initially maintained on buprenorphine (0.02 mg/kg i.v. q 8 hr) and amoxicillin/clavulanate as above. Meloxicam (0.3 mg/kg s.c.) was administered once the cat was fully recovered and he was subsequently discharged on oral amoxicillin/clavulanate and meloxicam.

Clinical Tip

Feline High-Rise Syndrome

Feline high-rise syndrome refers to trauma sustained by a cat falling from a height, typically a balcony or window of a building in an urban area. This syndrome occurs most commonly in younger cats. An extensive list of traumatic injuries has been reported in cats falling from a height but the most frequently identified include limb fractures (most cats have only a single fracture), thoracic injuries (especially pneumothorax and pulmonary contusions), nonfracture-related contusions and facial injuries. A relationship between the height fallen and the distribution of injuries has been suggested but clearly each case needs to be evaluated on an individual basis.