5 Analgesia for the emergency patient

Pain in Companion Animals

The advantages that the ability to feel pain confers with respect to survival are well recognized. However, on-going pain results in a number of physiological and psychological responses that are disadvantageous to any animal and especially one that is affected by illness or injury. These are summarized in Box 5.1.

Pain assessment

Nursing Aspect

Nurses should be considered central to on-going pain assessment as they typically spend more time with and around hospitalized patients. They are therefore often better suited to detect changes in pain status, especially as most of the signs of pain in companion animals are subjective.

The assessment of pain in animals is more difficult and more subjective than in people and veterinary personnel have to rely much more on a combination of sign recognition, patient interaction, experience, and a degree of anthropomorphism. The signs that an animal in pain may exhibit depend on various factors, including:

Signs consistent with pain are summarized in Box 5.2 in no particular order and it is important to realize that these signs are derived from both patient observation and interaction. Painful cats are often much less demonstrative than painful dogs, and sick animals in general may be unable to show expected behavioural signs of pain. In addition, physiological parameters are not consistently reliable as indicators of pain.

Clinical Tip

The pain pathway

A basic knowledge of the pain pathway is essential to understand the modes of action of available analgesics and the rationale behind multimodal therapy. The pain pathway essentially consists of the following.

Sensitization

Sensitization (or wind-up) refers to increased sensitivity to noxious stimuli following injury to either peripheral tissues (causes inflammatory pain) or the central nervous system (causes neuropathic pain). This increased sensitivity results in:

Sensitization can occur in either or both of the peripheral and central components of the pain pathway.

The clinical relevance of sensitization

In practical terms, once sensitization is underway, conscious perception of pain is greater, it is more difficult to control and higher drug doses are required. It is therefore preferable to try to prevent pain rather than merely to treat it once it is established. A significant proportion of emergency patients are already in pain at initial presentation. In order to minimize sensitization, pain management should be instituted as soon as possible and, once the pain is under control, the patient kept on a level pain-free plateau. All animals going on to have operative procedures performed will benefit from adequate preoperative analgesia, i.e. in advance of the significant noxious stimulation resulting from surgical intervention.

Analgesic Agents

Balanced analgesia involves the use of one or more appropriate analgesics (multimodal therapy) in an effective dosing regimen given by the appropriate route(s). Analgesic agents that are commonly available in emergency clinics include:

An intuitive approach to pain management is based on thorough initial evaluation followed by regular reassessment of the patient and adjustment of the treatment protocol as indicated. This is especially relevant to the use of full agonist opioids which may be used at highly variable dose rates and dosing frequencies. As described later in this chapter, nonpharmacological measures are also very important in pain management.

Opioids

Clinical Tip

Opioids (predominantly) act in the central component of the pain pathway. Most opioids used clinically are selective for the µ-receptor and are full (pure) agonists, partial agonists or agonists–antagonists. They are the mainstay of pain management in the emergency patient and block central sensitization. Opioids are also used in low doses for sedation or anxiolysis. High doses of pure opioids in particular may result in dysphoria (vocalization, anxiety, restlessness) that can be difficult to differentiate from on-going pain. Naloxone (or butorphanol) can be used to reverse the effects of full opioid agonists.

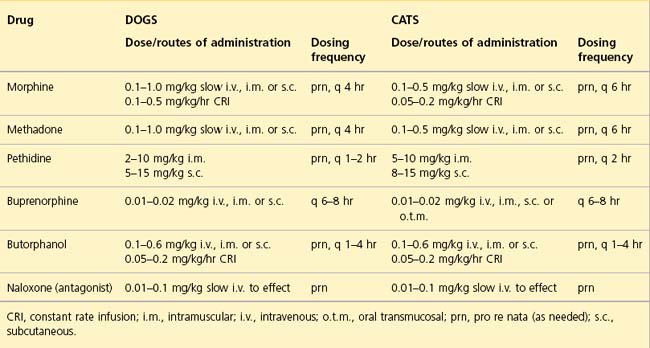

Both respiratory depression and bradycardia are rarely seen as side effects of concern during opioid administration in clinical veterinary patients that are not under anaesthesia. Furthermore, pain itself can cause respiratory compromise and appropriate opioid administration can normalize respiratory status in such cases. Until adequately treated, pain can also confuse assessment of other parameters such as heart rate and blood pressure. Dose rates, routes of administration and dosing frequencies of opioids in current use in emergency clinics are summarized in Table 5.1.

Morphine

Morphine is a full µ-agonist and remains the gold standard analgesic for moderate to severe pain. Onset of action is usually 10–15 minutes following intravenous administration. In addition to its analgesic effects, morphine is also extremely useful as an anxiolytic in respiratory distress. Vomiting is more likely than with other opioids and will further exacerbate raised intracranial or intraocular pressure. Morphine should therefore be avoided in patients where this is of concern. Rapid intravenous administration may cause signs associated with histamine release (transient vasodilation and hypotension) and slow intravenous boluses or a constant rate infusion are recommended.

Methadone

Methadone is a full µ-agonist that has the same or greater potency as morphine. Its sedative and dysphoric effects are reportedly less marked than with morphine and it does not typically induce emesis. Methadone does not cause histamine release following intravenous administration. In the author’s experience, panting (due to effects on the thermoregulatory centre) occurs much more commonly following methadone administration in dogs than it does with morphine and this may complicate clinical assessment.

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a partial µ-agonist and a κ-antagonist. It has a slow onset of action that is typically up to 45 min and is therefore not useful for rapid management of pain. Buprenorphine is indicated for mild to moderate pain and appears to be especially effective as an analgesic in cats. The mixed agonist–antagonist actions of this opioid mean that doses above a certain level may be progressively less effective (i.e. buprenorphine has a bell-shaped dose–response curve with a ceiling effect). This means that in theory there is limited capacity to increase the administered dose of buprenorphine in an animal that remains painful. However, the ceiling may be higher than the typical clinical dose range used and this may therefore be more of a theoretical concern. Furthermore, buprenorphine is reported to have a strong receptor affinity and in theory clinical doses of alternative opioids are therefore unlikely to be effective for a variable but lengthy period of time, i.e. until the buprenorphine has detached from the receptors. However, clinical experience suggests that full agonists can be used effectively much sooner than traditionally thought possible.

Oral (orogastric) buprenorphine preparations are available for people but have not been widely used in veterinary medicine. However, oral transmucosal administration of injectable buprenorphine at standard clinical doses results in similar pharmacokinetics to intravenous administration. The solution is tasteless and does not typically cause salivation or nausea. Oral transmucosal administration of buprenorphine is therefore a useful option in cats requiring continued short-term analgesia at home, either in addition to an NSAIA or where the use of an NSAIA is inappropriate. The drug is administered under the tongue or in the side of the mouth.

Butorphanol

Butorphanol is both a µ–antagonist and a κ-agonist with an onset of action of 15–20 minutes. Like buprenorphine, its analgesic effect is likely to reach a ceiling as the dose increases. Clinically, butorphanol seems more useful for its sedative and antitussive effects than as a potent analgesic. It may also be used to reverse sedation and respiratory depression associated with full µ-agonist opioid use.

Tramadol

Tramadol is an entirely synthetic centrally acting analgesic that has been widely used in people and with which there is growing and encouraging veterinary experience. Its analgesic efficacy is derived from complex interactions between opiate (primarily µ), serotonin and adrenergic receptor systems. At least one metabolite (O-desmethyltramadol; M1) is significantly active and may be essential in tramadol’s opioid effect. Tramadol is also reported to have antitussive activity.

While a range of adverse effects are theoretically possible, the main clinically relevant side effects are sedation and nausea. The potential for cardiovascular and respiratory depression may be greater following parenteral (intravenous) administration but is unlikely to be clinically relevant when used judiciously (the injectable preparation is not currently available in the USA). Naloxone will partially antagonize the effects of tramadol. The recommended dose range for dogs is 1–5 mg/kg q 6–12 hr a similar range is likely to be appropriate for cats; pharmacokinetic data suppoprts starting at the lower end of the dose range and upper end of the dosing interval.

An oral preparation of tramadol is available that also contains paracetamol (acetaminophen) – its use should therefore be avoided in cats.

Titration

Clinical Tip

Animals presenting in pain need to be constantly reassessed following initial treatment to ensure that treatment has been effective. Full opioids – morphine, methadone – are typically the most appropriate analgesic agents for use in moderate to severe pain. Their efficacy, rapid onset of action, linear dose–response curve and high index of safety make them highly suitable for titration in severe pain management.

Constant rate infusions

Constant rate infusions (CRI) of opioids (morphine in particular), as well as ketamine and lidocaine, are in widespread use in referral emergency centres as they offer clear advantages for pain management and most of the cases in question will have intravenous access available. CRIs avoid the peaks and troughs in plasma drug concentrations associated with intermittent boluses. They also provide more sensitive control over the degree of analgesia being provided, thereby avoiding both breakthrough pain and overdosing. There is no reason why this mode of drug administration cannot be employed in the first opinion setting as long as facilities allow and adequate monitoring is available.

Clinical Tip

Although some institutions use standardized prepared stock solutions of morphine, lidocaine and ketamine (MLK) for convenience, the author prefers to make up the CRI solution on an individual patient basis with the initial concentrations being guided by the patient in question. An example of how to prepare an MLK solution is given in Box 5.3.

BOX 5.3 Preparation of a morphine, lidocaine and ketamine (MLK) solution for constant rate infusion

Note: it is extremely important to ensure that two individuals check all of the above calculations and all of the volumes of analgesic agents and crystalloid removed/added. This safeguard will hopefully prevent potentially serious errors from occurring.

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents

Clinical Tip

NSAIAs in general reduce the severity of the peripheral inflammatory response and minimize peripheral sensitization. They may be useful in moderate to severe pain and are especially effective as analgesics when used in combination with opioids – the overall analgesia achieved is greater when these agents are used together than when either is used alone. Multimodal therapy may also allow lower doses of each agent to be used, thereby reducing the risk of side effects.

The effects of most NSAIAs are related to the impairment of prostaglandin production. This involves cyclooxygenase (COX) of which there are (at least) two types. COX-1 (constitutive, housekeeping) is variably found in all tissues of the body and is involved in the production of prostaglandins that are essential for a variety of normal functions. Levels of COX-2 (inducible) on the other hand are typically very low but increase during tissue injury. It is primarily responsible for the production of prostaglandins that mediate the inflammatory response and pain associated with tissue injury. Most NSAIAs are COX inhibitors. Newer agents (e.g. carprofen, meloxicam) have more selective inhibition of COX-2 versus COX-1 and may be associated with fewer side effects and a safer therapeutic index.

Side effects/contraindications

The two most commonly recognized side effects and/or contraindications of NSAIA use are gastroduodenal injury and renal injury.

Gastroduodenal injury

Prostaglandins are important for the integrity of the gastrointestinal mucosal barrier and their impaired production therefore increases the likelihood of mucosal injury (haemorrhage, erosions, ulceration) in an already compromised tissue. Intuitively therefore NSAIAs are contraindicated in animals with gastrointestinal abnormalities. However, there are patients with gastrointestinal signs in which the use of an NSAIA may be justified – examples include a dog that is heavily dependent on NSAIA therapy to manage discomfort associated with chronic osteoarthritis (for which opioids are less effective). Considerations in such cases include the following:

Renal injury

Prostaglandins are not critically involved in renal haemodynamics in normal healthy animals. However, in response to a decrease in renal blood flow, locally acting prostaglandins serve to protect renal perfusion. Their inhibition by NSAIA therapy can therefore result in renal ischaemia and insufficiency. This is applicable to both older NSAIAs and newer agents with more selective COX-2 inhibition as constitutive COX-2 is produced in the kidney. Emergency patients in whom renal blood flow may be decreased include those with hypovolaemia, cardiac insufficiency and pre-existing renal disease.

Other side effects of NSAIAs described include effects on the liver and interference with coagulation (see Ch. 30).

Paracetamol (acetaminophen)

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is not commonly used therapeutically in veterinary medicine due to the widespread availability of licensed veterinary products that are both effective and have been subjected to extensive clinical trialling. However, paracetamol is widely available from numerous outlets and frequently present within the home of many pet owners. It is therefore common in emergency practice either to receive enquiries about administering paracetamol to dogs and cats or to see animals to which this agent has been administered.

Paracetamol may be a useful (and possibly underused) analgesic in dogs but it should never be administered to cats at any dose. It is an NSAIA and interferes with prostaglandin synthesis but does not work via inhibition of COX-1 or COX-2. Although this makes it a poor antiinflammatory agent, it does result in minimal gastrointestinal side effects. Paracetamol can therefore be used either in addition to conventional NSAIAs or alone in dogs in which these agents are contraindicated or poorly tolerated. As paracetamol interferes with prostaglandin production, it should be avoided in hypoperfused or dehydrated patients. Hepatotoxicity is a potential side effect of this drug. The recommended dose range in dogs is 10–15 mg/kg p.o. q 8–12 hr.

Local anaesthetic agents

Local anaesthetic agents work by blocking sensory input via afferent nerve fibres to the central nervous system and prevent central sensitization. Longer-acting agents in particular (e.g. bupivacaine, ropivacaine) are used extensively in referral centres in a number of ways, including:

While these uses may not be applicable to most nonreferral emergency patients, local anaesthetic agents can be employed to good effect in this setting.

Lidocaine

Lidocaine has a shorter duration of action (1–2 hr) than other agents but a rapid onset of action (can be as quick as 3–5 min). It is the most widely available local anaesthetic agent and may be used for emergency cases in a number of ways. For example:

Ketamine

Ketamine is a dissociative anaesthetic agent that is used most commonly for sedation (see Ch. 39). However, it also has analgesic properties and blocks (and potentially reverses) central sensitization via its action as an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist. It is especially effective in this respect when combined with a full opioid agonist and may be used as a CRI (see Box 5.3). The recommended dose for analgesic purposes is 0.1–1 mg/kg i.v. as needed (often every 30 minutes) or a single loading dose followed by a constant rate infusion of 0.1–1 mg/kg/hr.

Medetomidine

Medetomidine is an alpha2-adrenergic agonist that is also used most commonly for its sedative properties (see Ch. 39). This agent does, however, also possess potent analgesic properties and can be a useful adjunctive analgesic in some cases. At the microdoses recommended here, cardiovascular and respiratory effects should be minimal and can be reversed by atipamezole if necessary. The sedative effects are likely to be advantageous for patient management in those cases in which this agent may be employed as an analgesic. Recommended doses for medetomidine when used for analgesic purposes are 2–5 µg/kg slow i.v. or i.m. as needed (often q 30–90 minutes but potentially much longer if an opioid is used concurrently); alternatively, a CRI of 1–3 µg/kg/hr may be used.

Sedation

Although sedation is not a substitute for pain relief, it can be invaluable in improving the welfare of animals that are especially anxious or distressed, allowing them to rest and to utilize their metabolic reserves for recovery rather than coping behaviour. In cases in which opioids being used for analgesia do not provide sufficient sedation, other agents such as acepromazine and benzodiazepines are options.

Non-pharmacological Measures

Nursing Aspect

Although analgesic agents are the mainstay of pain management, it is essential not to overlook the important contribution of good nursing care and other non-pharmacological measures. These measures reduce stress, improve patient wellbeing, and contribute significantly to pain management. Some of these measures are listed in Box 5.4.