Chapter 25 Physical Problems and Complications in the Puerperium

The need for women-centred and women-led postpartum care

The woman’s social and ethnic environment should take into account their individual perceptions and experiences surrounding the pregnancy and the birth event. Where the birth involved complications, postpartum care is likely to differ from that of women whose pregnancy and labour are considered straightforward; the role of the midwife in these cases is:

Immediate untoward events for the mother following the birth of the baby

Postpartum haemorrhage

Immediate (primary) postpartum haemorrhage (PPH). This is the most immediate and potentially life-threatening event occurring at the point, or within 24 hours, of delivery of the placenta and membranes. It presents as a sudden and excessive vaginal blood loss of 500 ml or more. (See Ch. 19 for management.)

Immediate (primary) postpartum haemorrhage (PPH). This is the most immediate and potentially life-threatening event occurring at the point, or within 24 hours, of delivery of the placenta and membranes. It presents as a sudden and excessive vaginal blood loss of 500 ml or more. (See Ch. 19 for management.)

Secondary or delayed PPH. This is where there is excessive or prolonged vaginal loss from 24 hours after delivery of the placenta and for up to 12 weeks postpartum. Unlike primary PPH, which includes a specified volume of blood loss as part of its definition, there is no such volume defined for secondary PPH.

Secondary or delayed PPH. This is where there is excessive or prolonged vaginal loss from 24 hours after delivery of the placenta and for up to 12 weeks postpartum. Unlike primary PPH, which includes a specified volume of blood loss as part of its definition, there is no such volume defined for secondary PPH.

Regardless of the timing of any haemorrhage, it is most frequently the placental site that is the source. Alternatively, a cervical or deep vaginal wall tear or trauma to the perineum might be the cause in women who have recently given birth. Retained placental fragments or other products of conception are likely to inhibit the process of involution, or reopen the placental wound. The diagnosis is likely to be determined by the woman’s condition and pattern of events and is also often complicated by the presence of infection (see Box 25.1).

Treatment

• Reassure the woman and her support person(s)

• Rub up a contraction by massaging the uterus if it is still palpable

• Encourage the mother to empty her bladder

• Give an uterotonic drug, such as ergometrine maleate, by the intravenous or intramuscular route

• Keep all pads and linen to assess the volume of blood lost

• Antibiotics may be prescribed

• If retained products of conception are seen on an ultrasound scan, it may be appropriate to transfer the woman to hospital and prepare her for theatre

Postpartum complications and identifying deviations from the normal

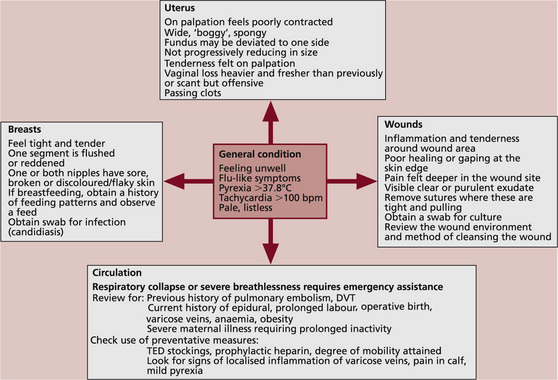

The midwife needs to establish whether there are any signs of possible morbidity and determine whether these might indicate the need for referral. Figure 25.1 suggests a model for linking together key observations that suggest potential risk of, or actual, morbidity.

Fig. 25.1: Diagrammatic demonstration of the relationship between deviation from normal physiology and potential morbidity.

The central point, as with any personal contact, is the midwife’s initial review of the woman’s appearance, psychological state and vital signs.

A rise in temperature above 37.8°C is usually considered to be of clinical significance. A mildly raised temperature may be related to normal physiological hormonal responses: e.g. the increasing production of breast milk.

A rise in temperature above 37.8°C is usually considered to be of clinical significance. A mildly raised temperature may be related to normal physiological hormonal responses: e.g. the increasing production of breast milk.

A weak and rapid pulse rate in a woman who is in a state of collapse with signs of shock and a low blood pressure, but no evidence of vaginal haemorrhage, may indicate the formation of a haematoma. A rapid pulse rate in an otherwise well woman might suggest that she is anaemic but could also indicate increased thyroid or other dysfunctional hormonal activity.

A weak and rapid pulse rate in a woman who is in a state of collapse with signs of shock and a low blood pressure, but no evidence of vaginal haemorrhage, may indicate the formation of a haematoma. A rapid pulse rate in an otherwise well woman might suggest that she is anaemic but could also indicate increased thyroid or other dysfunctional hormonal activity.

The midwife needs to be alert to any possible relationship between the observations overall and their potential cause, keeping common illnesses in mind – e.g. the woman may have a common cold.

The midwife needs to be alert to any possible relationship between the observations overall and their potential cause, keeping common illnesses in mind – e.g. the woman may have a common cold.

The uterus and vaginal loss following vaginal birth

Assessment of uterine involution is needed where the woman:

Where palpation of the uterus identifies deviation to one side, this might be the result of a full bladder. Where the woman had emptied her bladder prior to palpation, the presence of urinary retention must be considered. Catheterisation of the bladder in these circumstances is indicated for two reasons: to remove any obstacle that is preventing the process of involution taking place and to provide relief to the bladder itself. If deviation is not the result of a full bladder, further investigations need to be undertaken to determine the cause.

Morbidity might be suspected where the uterus:

This might be described as subinvolution of the uterus, which can indicate postpartum infection, or the presence of retained products of the placenta or membranes, or both.

Vulnerability to infection: potential causes and prevention

The bacteria responsible for the majority of puerperal infections belong to the streptococcal or staphylococcal species.

The Streptococcus bacterium may be haemolytic or non-haemolytic, aerobic or anaerobic; e.g. beta-haemolytic S. pyogenes (Lancefield group A).

The Streptococcus bacterium may be haemolytic or non-haemolytic, aerobic or anaerobic; e.g. beta-haemolytic S. pyogenes (Lancefield group A).

The Staphylococcus bacterium has a grape-like structure; the most important species are Staph. aureus or pyogenes. Staphylococci are the most frequent cause of wound infections; where these bacteria are coagulase-positive they form clots on the plasma, which can lead to more widespread systemic morbidity. There is additional concern about their resistance to antibiotics and about subsequent management to control spread of the infection.

The Staphylococcus bacterium has a grape-like structure; the most important species are Staph. aureus or pyogenes. Staphylococci are the most frequent cause of wound infections; where these bacteria are coagulase-positive they form clots on the plasma, which can lead to more widespread systemic morbidity. There is additional concern about their resistance to antibiotics and about subsequent management to control spread of the infection.

The uterus and vaginal loss following operative delivery

It may be some hours after the operation before the woman sits up or moves about. Blood and debris will have been slowly released from the uterus during this time and, when the woman begins to move, this will be expelled though the vagina and may appear as a substantial fresh-looking red loss. Following this initial event, it is usual for the amount of vaginal loss to lessen and for further fresh loss to be minimal. All this can be observed without actually palpating the uterus, which is likely to be very painful in the first few days after the operation.

Where clinically indicated – for example, where vaginal bleeding is heavier than expected – the uterine fundus can be gently palpated. If the uterus is not well contracted, then medical intervention is needed. The following may be required:

Wound problems

Perineal problems

Severe perineal pain might be the result of:

The blood contained within a haematoma can exceed 1000 ml and may significantly affect the overall state of the woman, who can present with signs of acute shock. Treatment is by evacuation of the haematoma and resuturing of the perineal wound, usually under a general anaesthetic.

Oedema can cause the stitches to feel excessively tight. Local application of cold packs, oral analgesia, as well as complementary medicines such as arnica and witch hazel, may bring relief.

Pain in the perineal area that occurs at a later stage or pain that reoccurs might be associated with an infection. The skin edges are likely to have a moist, puffy and dull appearance; there may also be an offensive odour and evidence of pus in the wound.

A swab should be obtained for micro-organism culture and referral should be made to a GP.

A swab should be obtained for micro-organism culture and referral should be made to a GP.

Antibiotics might be commenced immediately when there is specific information about any infective agent.

Antibiotics might be commenced immediately when there is specific information about any infective agent.

Advice should be given about cleaning the area, using cotton underwear, avoiding tights and trousers and changing sanitary pads frequently.

Advice should be given about cleaning the area, using cotton underwear, avoiding tights and trousers and changing sanitary pads frequently.

Women should also be advised to avoid using perfumed bath additives or talcum powder.

Women should also be advised to avoid using perfumed bath additives or talcum powder.

If the perineal area fails to heal or continues to cause pain by the time the initial healing process should have begun, resuturing or refashioning might be advised. Women should be pain free and able to resume sexual intercourse without pain by 6 weeks after the birth; some discomfort might still be present, however, depending on the degree of trauma experienced.

Caesarean section wounds

It is now common practice for women undergoing an operative birth to be given prophylactic antibiotics at the time of the surgery. This has been demonstrated to reduce the incidence of subsequent wound infection and endometritis significantly. It is usual for the wound dressing to be removed after the first 24 hours, as this also aids healing and reduces infection.

A wound that is hot, tender and inflamed and is accompanied by a pyrexia is highly suggestive of an infection. Where this is observed:

Haematoma and abscesses can also form underneath the wound, and women may identify increased pain around the wound where these are present. Rarely, a wound may need to be probed to reduce the pressure and to allow infected material to drain, reducing the likelihood of the formation of an abscess.

Circulation problems

Pulmonary embolism remains a major cause of maternal deaths in the UK. Women at higher risk include those with the factors listed in Box 25.2.

Women who undergo surgery and have these pre-existing factors should be:

provided with TED stockings during, or as soon as possible after, the birth

provided with TED stockings during, or as soon as possible after, the birth

prescribed prophylactic heparin until they attain normal mobility.

prescribed prophylactic heparin until they attain normal mobility.

Clinical signs that women might report include the following conditions (the most common given first, progressing to the most serious):

Signs of circulatory problems related to varicose veins usually include localised inflammation or tenderness around the varicose vein, sometimes accompanied by a mild pyrexia. This is superficial thrombophlebitis, which is usually resolved by applying support to the affected area and administering anti-inflammatory drugs, where these do not conflict with other medication being taken or with breastfeeding.

Signs of circulatory problems related to varicose veins usually include localised inflammation or tenderness around the varicose vein, sometimes accompanied by a mild pyrexia. This is superficial thrombophlebitis, which is usually resolved by applying support to the affected area and administering anti-inflammatory drugs, where these do not conflict with other medication being taken or with breastfeeding.

Unilateral oedema of an ankle or calf, accompanied by stiffness or pain and a positive Homan’s sign, might indicate a deep vein thrombosis that has the potential to cause a pulmonary embolism. Urgent medical referral must be made to confirm the diagnosis and commence anticoagulant or other appropriate therapy.

Unilateral oedema of an ankle or calf, accompanied by stiffness or pain and a positive Homan’s sign, might indicate a deep vein thrombosis that has the potential to cause a pulmonary embolism. Urgent medical referral must be made to confirm the diagnosis and commence anticoagulant or other appropriate therapy.

The most serious outcome is the development of a pulmonary embolism. The first sign might be the sudden onset of breathlessness, which may not be associated with any obvious clinical sign of a blood clot. Women with this condition are likely to become seriously ill and could suffer respiratory collapse with very little prior warning.

The most serious outcome is the development of a pulmonary embolism. The first sign might be the sudden onset of breathlessness, which may not be associated with any obvious clinical sign of a blood clot. Women with this condition are likely to become seriously ill and could suffer respiratory collapse with very little prior warning.

Some degree of oedema of the lower legs, ankles and feet can be viewed as being within normal limits where it is not accompanied by calf pain (especially unilaterally), pyrexia or raised blood pressure.

Hypertension

Women who have had previous episodes of hypertension in pregnancy may continue to demonstrate this postpartum. Mothers with clinical signs of pregnancy-induced hypertension still run the risk of developing eclampsia in the hours and days following the birth, although this is a relatively rare outcome in the normal population. Some degree of blood pressure monitoring should be continued for women who suffered hypertension antenatally, and postpartum management should proceed on an individual basis. For these women the medical advice should cover:

optimal systolic and diastolic levels

optimal systolic and diastolic levels

instructions for treatment with antihypertensive drugs if the blood pressure exceeds these levels.

instructions for treatment with antihypertensive drugs if the blood pressure exceeds these levels.

Occasionally, women can develop postnatal pre-eclampsia without associated antenatal problems. Therefore, if a postpartum woman presents with signs associated with pre-eclampsia, the midwife should:

For women with essential hypertension, management of their overall medical condition will be reviewed postpartum by their usual caregivers.

Headache

Concern about postpartum morbidity should centre around the history of:

If an epidural anaesthetic was administered for the birth (or at any time postpartum), medical advice should be sought and the anaesthetist who sited the epidural might need to be contacted. Headaches from a dural tap typically arise once the woman has become mobile after the birth; these headaches are at their most severe when the woman is standing, lessening when she lies down. They are often accompanied by:

These headaches are very debilitating and are best managed by stopping the leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) by the insertion of 10–20 ml of blood into the epidural space; this should resolve the clinical symptoms. If women have returned home after the birth, they would need to return to the hospital to have this procedure carried out.

Headaches might also be precursors of psychological distress.

Backache

Many women experience pain or discomfort from backache in pregnancy as a result of separation or diastasis of the abdominal muscles (rectus abdominis diastasis, RAD). It might be sufficient to:

give advice on skeletal support to attain a good posture when feeding and lifting

give advice on skeletal support to attain a good posture when feeding and lifting

suggest a feasible personal exercise plan and how to achieve this

suggest a feasible personal exercise plan and how to achieve this

Where backache is causing pain that affects the woman’s activities of daily living, referral can be made to local physiotherapy services. If the symphysis pubis has been affected in pregnancy, this should resolve in the weeks after the baby is born.

Urinary problems

A short period of poor bladder control may be present for a few days after the birth, but this should resolve within a week. Epidural or spinal anaesthetic can have an effect on the neurological sensors that control urine release and flow; this might cause acute retention. Women with perineal trauma may have difficulty in deciding whether they have normal urinary control; retention of urine might be detected by the midwife as a result of abdominal palpation of the uterus. Abdominal tenderness in association with other urinary symptoms – for example, poor output, dysuria or offensive urine, and a pyrexia or general flu-like symptoms – might indicate a urinary tract infection. Very rarely, urinary incontinence might be a result of a urethral fistula following complications from the labour or birth.

The main complication of any form of urine retention is that the uterus might be prevented from effective contraction, which leads to increased vaginal blood loss. There is also increased potential for the development of a urine infection.

It is not uncommon for some women to have a small degree of leakage or retention of urine within the first 2 or 3 days after the birth while the tissues are recovering, but this should resolve with the practice of postnatal exercise and healing of any localised trauma. Referral to a physiotherapist might be appropriate. Specific enquiry about these issues should be made when women attend for their 6-week postnatal examination.

Bowels and constipation

Normal bowel pattern should return within days of the birth. Women who have haemorrhoids or difficulty with constipation should be given:

advice on following a diet high in fibre and fluids, preferably water

advice on following a diet high in fibre and fluids, preferably water

instructions on the use of appropriate laxatives to soften the stools

instructions on the use of appropriate laxatives to soften the stools

It is also a matter of concern if women experience a loss of bowel control or faecal incontinence. It is important to determine the nature of the incontinence and distinguish it from an episode of diarrhoea. Women who identify any change to their prepregnant bowel pattern by the end of the puerperal period should have this reviewed.

Anaemia

The impact of the events of the labour and birth may leave many women looking pale and tired for a day or so afterwards.

Where it is evident that a larger than normal blood loss has occurred, red blood cell volume and haemoglobin (Hb) can be assessed and appropriate treatment provided to reduce the effects of anaemia.

Where it is evident that a larger than normal blood loss has occurred, red blood cell volume and haemoglobin (Hb) can be assessed and appropriate treatment provided to reduce the effects of anaemia.

Where the Hb level is less than 9.0 g/dl, a blood transfusion might be appropriate; oral iron and appropriate dietary advice are advocated when women decline a blood transfusion or when the Hb level is less than 11.0 g/dl.

Where the Hb level is less than 9.0 g/dl, a blood transfusion might be appropriate; oral iron and appropriate dietary advice are advocated when women decline a blood transfusion or when the Hb level is less than 11.0 g/dl.

If Hb values have not been assessed, clinical symptoms such as lethargy, tachycardia, breathlessness or pale mucous membranes may suggest anaemia; a blood profile should then be considered.

If Hb values have not been assessed, clinical symptoms such as lethargy, tachycardia, breathlessness or pale mucous membranes may suggest anaemia; a blood profile should then be considered.

Breast problems

Regardless of whether women are breastfeeding, they may experience tightening and enlargement of their breasts towards the 3rd or 4th day, as hormonal influences encourage the breasts to produce milk.

For women who are breastfeeding, the general advice is to feed the baby and avoid excessive handling of the breasts. Simple analgesics may be required to reduce discomfort.

For women who are breastfeeding, the general advice is to feed the baby and avoid excessive handling of the breasts. Simple analgesics may be required to reduce discomfort.

For women who are not breastfeeding, the advice is to ensure that the breasts are well supported but that the support is not too constrictive; again, taking regular analgesia for 24–48 hours should reduce any discomfort. Heat and cold applied to the breasts via a shower or soaking in the bath may temporarily relieve acute discomfort.

For women who are not breastfeeding, the advice is to ensure that the breasts are well supported but that the support is not too constrictive; again, taking regular analgesia for 24–48 hours should reduce any discomfort. Heat and cold applied to the breasts via a shower or soaking in the bath may temporarily relieve acute discomfort.

It is important to gauge whether the duration of the engorgement is excessive and whether there are any other signs of a possible infection, such as overt tenderness or inflammation, pyrexia or flu-like symptoms. If infective mastitis is suspected, then antibiotics should be prescribed. If a woman is breastfeeding, it is important that this continues or that the breast milk is expressed.