Chapter 19 The Third Stage of Labour

Physiological processes

During the third stage of labour, separation and expulsion of the placenta and membranes occur as the result of an interplay of mechanical and haemostatic factors. The time at which the placenta actually separates from the uterine wall can vary. It may shear off during the final expulsive contractions accompanying the birth of the baby or remain adherent for some considerable time. The third stage usually lasts between 5 and 15 minutes, but any period up to 1 hour may be considered to be within normal limits.

Separation and descent of the placenta

Mechanical factors (Fig. 19.1)

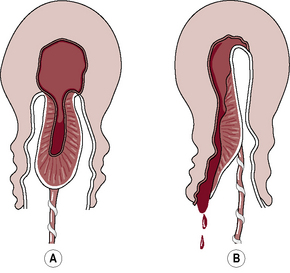

Separation usually begins centrally so that a retroplacental clot is formed (Fig. 19.2). Two methods of separation are described:

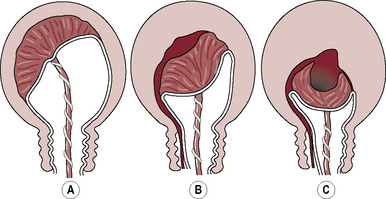

Schultze (Fig. 19.3A).

Schultze (Fig. 19.3A).

Matthews Duncan (Fig. 19.3B).

Matthews Duncan (Fig. 19.3B).

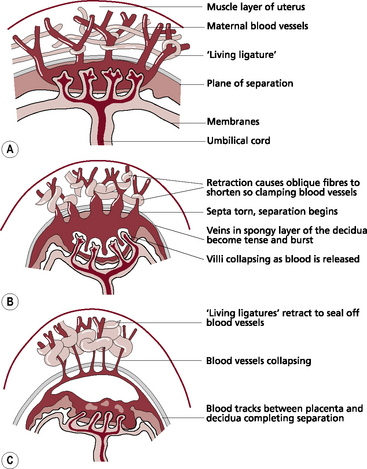

Fig. 19.1 The placental site during separation. (A) Uterus and placenta before separation. (B) Separation begins. (C) Separation is almost complete.

Fig. 19.2 The mechanism of placental separation. (A) Uterine wall is partially retracted, but not sufficiently to cause placental separation. (B) Further contraction and retraction thicken the uterine wall, reduce the placental site and aid placental separation. (C) Complete separation and formation of the retroplacental clot. Note: the thin lower segment has collapsed like a concertina following the birth of the baby.

Once separation has occurred, the uterus contracts strongly, forcing the placenta and membranes to fall into the lower uterine segment and finally into the vagina.

Haemostasis

The three factors that are critical to control of bleeding are the following:

Retraction of the oblique uterine muscle fibres in the upper uterine segment through which the tortuous blood vessels intertwine.

Retraction of the oblique uterine muscle fibres in the upper uterine segment through which the tortuous blood vessels intertwine.

The presence of vigorous uterine contraction following separation – this brings the walls into apposition so that further pressure is exerted on the placental site.

The presence of vigorous uterine contraction following separation – this brings the walls into apposition so that further pressure is exerted on the placental site.

The achievement of haemostasis – following separation, the placental site is rapidly covered by a fibrin mesh utilising 5–10% of the circulating fibrinogen.

The achievement of haemostasis – following separation, the placental site is rapidly covered by a fibrin mesh utilising 5–10% of the circulating fibrinogen.

Management of the third stage

Uterotonics or uterotonic agents

These are drugs (e.g. Syntometrine, Syntocinon, ergometrine and prostaglandins) that stimulate the smooth muscle of the uterus to contract. They may be administered with crowning of the baby’s head, at the time of birth of the anterior shoulder of the baby, at the end of the second stage of labour or following the delivery of the placenta.

Information related to the best available research information on the use of uterotonic drugs during the third stage of labour should be provided in an objective manner.

Expectant or physiological management

In the event of expectant management:

routine administration of the uterotonic drug is withheld

routine administration of the uterotonic drug is withheld

the umbilical cord is left unclamped until cord pulsation has ceased or the mother requests it to be clamped, or both

the umbilical cord is left unclamped until cord pulsation has ceased or the mother requests it to be clamped, or both

the placenta is expelled by use of gravity and maternal effort.

the placenta is expelled by use of gravity and maternal effort.

With this approach, therapeutic uterotonic administration would be administered either to stop bleeding once it has occurred or to maintain the uterus in a contracted state when there are indications that excessive bleeding is likely to occur.

Active management

This is a policy whereby prophylactic administration of a uterotonic is applied, regardless of the assessed obstetric risk status of the woman. This is undertaken in conjunction with clamping of the umbilical cord shortly after birth of the baby and delivery of the placenta by the use of controlled cord traction. One of the following uterotonic drugs is usually used:

Combined ergometrine and oxytocin

(A commonly used brand is Syntometrine.)

A 1-ml ampoule contains 5 IU of oxytocin and 0.5 mg ergometrine and is administered by intramuscular injection.

A 1-ml ampoule contains 5 IU of oxytocin and 0.5 mg ergometrine and is administered by intramuscular injection.

The oxytocin acts within 2.5 minutes, and the ergometrine within 6–7 minutes.

The oxytocin acts within 2.5 minutes, and the ergometrine within 6–7 minutes.

Their combined action results in a rapid uterine contraction enhanced by a stronger, more sustained contraction lasting several hours.

Their combined action results in a rapid uterine contraction enhanced by a stronger, more sustained contraction lasting several hours.

Administered, normally, at birth of the anterior shoulder.

Administered, normally, at birth of the anterior shoulder.

Caution. No more than two doses of ergometrine 0.5 mg should be given, as it can cause headache, nausea and an increase in blood pressure; it is normally contraindicated where there is a history of hypertensive or cardiac disease.

Caution. No more than two doses of ergometrine 0.5 mg should be given, as it can cause headache, nausea and an increase in blood pressure; it is normally contraindicated where there is a history of hypertensive or cardiac disease.

Clamping of the umbilical cord

This may have been carried out during birth of the baby if the cord was tightly around the neck. Early clamping is carried out in the first 1–3 minutes immediately after birth, regardless of whether cord pulsation has ceased.

Proponents of late clamping suggest that no action be taken until cord pulsation ceases or the placenta has been completely delivered, thus allowing the physiological processes to take place without intervention.

Delivery of the placenta and membranes

Controlled cord traction (CCT)

This manœuvre is believed to reduce blood loss and shorten the third stage of labour, therefore minimising the time during which the mother is at risk from haemorrhage. It is designed to enhance the normal physiological process. Before starting CCT check that the conditions listed in Box 19.1 have been met. At the beginning of the third stage, a strong uterine contraction results in the fundus being palpable below the umbilicus. It feels broad, as the placenta is still in the upper segment. As the placenta separates and falls into the lower uterine segment there is a small fresh blood loss, the cord lengthens and the fundus becomes rounder, smaller and more mobile as it rises in the abdomen. (Note: there is a school of thought that does not believe it is necessary to wait for signs of separation and descent but the uterus must be well contracted and care exerted with cord traction.)

It is important not to manipulate the uterus in any way, as this may precipitate incoordinate action. No further step should be taken until a strong contraction is palpable. If tension is applied to the umbilical cord without this contraction, uterine inversion may occur (see Ch. 23).

When CCT is the preferred method of management, the following sequence of actions is usually undertaken:

Once the uterus is found on palpation to be contracted, one hand is placed above the level of the symphysis pubis with the palm facing towards the umbilicus and exerting pressure in an upwards direction. This is countertraction.

Once the uterus is found on palpation to be contracted, one hand is placed above the level of the symphysis pubis with the palm facing towards the umbilicus and exerting pressure in an upwards direction. This is countertraction.

Grasping the cord, traction is applied in a downward and backward direction following the line of the birth canal.

Grasping the cord, traction is applied in a downward and backward direction following the line of the birth canal.

Some resistance may be felt but it is important to apply steady tension by pulling the cord firmly and maintaining the pressure. Jerky movements and force should be avoided.

Some resistance may be felt but it is important to apply steady tension by pulling the cord firmly and maintaining the pressure. Jerky movements and force should be avoided.

The aim is to complete the action as one continuous, smooth, controlled movement. However, it is only possible to exert this tension for 1 or 2 minutes, as it may be an uncomfortable procedure for the mother and the midwife’s hand will tire.

The aim is to complete the action as one continuous, smooth, controlled movement. However, it is only possible to exert this tension for 1 or 2 minutes, as it may be an uncomfortable procedure for the mother and the midwife’s hand will tire.

Downward traction on the cord must be released before uterine countertraction is relaxed, as sudden withdrawal of countertraction while tension is still being applied to the cord may also cause uterine inversion.

Downward traction on the cord must be released before uterine countertraction is relaxed, as sudden withdrawal of countertraction while tension is still being applied to the cord may also cause uterine inversion.

If the manœuvre is not immediately successful, there should be a pause before uterine contraction is again checked and a further attempt is made.

If the manœuvre is not immediately successful, there should be a pause before uterine contraction is again checked and a further attempt is made.

Should the uterus relax, tension is temporarily released until a good contraction is again palpable.

Should the uterus relax, tension is temporarily released until a good contraction is again palpable.

Once the placenta is visible, it may be cupped in the hands to ease pressure on the friable membranes.

Once the placenta is visible, it may be cupped in the hands to ease pressure on the friable membranes.

A gentle upward and downward movement or twisting action will help to coax out the membranes and increase the chances of delivering them intact. Great care should be taken to avoid tearing the membranes.

A gentle upward and downward movement or twisting action will help to coax out the membranes and increase the chances of delivering them intact. Great care should be taken to avoid tearing the membranes.

Expectant management

This management policy allows the physiological changes within the uterus that occur at the time of birth to take their natural course with minimal intervention; it excludes the administration of uterotonic drugs. The processes of placental separation and expulsion are quite distinct from one another and the signs of separation and descent must be evident before maternal effort can be used to expedite expulsion.

If sitting or squatting, gravity will aid expulsion.

If sitting or squatting, gravity will aid expulsion.

If good uterine contractions are sustained, maternal effort will usually bring about expulsion. The mother simply pushes, as during the second stage of labour.

If good uterine contractions are sustained, maternal effort will usually bring about expulsion. The mother simply pushes, as during the second stage of labour.

Encouragement is important, as by now she may be exhausted and the contractions will feel weaker and less expulsive than those during the second stage of labour.

Encouragement is important, as by now she may be exhausted and the contractions will feel weaker and less expulsive than those during the second stage of labour.

Providing that fresh blood loss is not excessive, the mother’s condition remains stable and her pulse rate normal, there need be no anxiety. This spontaneous process can take from 20 minutes to an hour to complete.

Providing that fresh blood loss is not excessive, the mother’s condition remains stable and her pulse rate normal, there need be no anxiety. This spontaneous process can take from 20 minutes to an hour to complete.

It is important that the midwife monitors uterine action by placing a hand lightly on the fundus. She can thus palpate the contraction while checking that relaxation does not result in the uterus filling with blood.

It is important that the midwife monitors uterine action by placing a hand lightly on the fundus. She can thus palpate the contraction while checking that relaxation does not result in the uterus filling with blood.

Vigilance is crucial, as it should be remembered that the longer the placenta remains undelivered, the greater is the risk of bleeding because the uterus cannot contract down fully while the bulk of the placenta is in situ.

Vigilance is crucial, as it should be remembered that the longer the placenta remains undelivered, the greater is the risk of bleeding because the uterus cannot contract down fully while the bulk of the placenta is in situ.

Early attachment of the baby to the breast may enhance these physiological changes by stimulating the release of oxytocin from the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland.

Early attachment of the baby to the breast may enhance these physiological changes by stimulating the release of oxytocin from the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland.

Asepsis

The need for asepsis is even greater now than in the preceding stages of labour. Laceration and bruising of the cervix, vagina, perineum and vulva provide a route for the entry of micro-organisms. The placental site, a raw wound, provides an ideal medium for infection. Strict attention to the prevention of sepsis is therefore vital.

Cord blood sampling

when the mother’s blood group is Rhesus negative or her Rhesus type is unknown

when the mother’s blood group is Rhesus negative or her Rhesus type is unknown

when atypical maternal antibodies have been found during an antenatal screening test

when atypical maternal antibodies have been found during an antenatal screening test

where a haemoglobinopathy is suspected (e.g. sickle cell disease).

where a haemoglobinopathy is suspected (e.g. sickle cell disease).

The sample should be taken from the fetal surface of the placenta where the blood vessels are congested and easily visible.

Completion of the third stage

Once the placenta is delivered, the uterus should be well contracted and fresh blood loss minimal.

Once the placenta is delivered, the uterus should be well contracted and fresh blood loss minimal.

Perineum and lower vagina checked for trauma.

Perineum and lower vagina checked for trauma.

Blood loss is estimated; including blood that has soaked into linen and swabs as well as measurable fluid loss and clot formation.

Blood loss is estimated; including blood that has soaked into linen and swabs as well as measurable fluid loss and clot formation.

A thorough inspection of the placenta or membranes must be carried out to make sure that no part has been retained.

A thorough inspection of the placenta or membranes must be carried out to make sure that no part has been retained.

If there is any suspicion that the placenta or membranes are incomplete, they must be kept for inspection and a doctor informed immediately.

If there is any suspicion that the placenta or membranes are incomplete, they must be kept for inspection and a doctor informed immediately.

Immediate care

It is advisable for mother and infant to remain in the midwife’s care for at least an hour after birth, regardless of the birth setting.

The woman should be encouraged to pass urine because a full bladder may impede uterine contraction.

The woman should be encouraged to pass urine because a full bladder may impede uterine contraction.

Uterine contraction and blood loss should be checked on several occasions during this first hour.

Uterine contraction and blood loss should be checked on several occasions during this first hour.

Throughout this same period the midwife should pay regard to the baby’s general wellbeing. She should check the security of the cord clamp and observe general skin colour, respirations and temperature.

Throughout this same period the midwife should pay regard to the baby’s general wellbeing. She should check the security of the cord clamp and observe general skin colour, respirations and temperature.

The warmest place for a baby to be placed is in a direct skin-to-skin contact position with the mother or wrapped and cuddled, whichever she prefers.

The warmest place for a baby to be placed is in a direct skin-to-skin contact position with the mother or wrapped and cuddled, whichever she prefers.

Most women intending to breastfeed will wish to put their baby to the breast during these early moments of contact.

Most women intending to breastfeed will wish to put their baby to the breast during these early moments of contact.

Complications of the third stage of labour

Postpartum haemorrhage

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is defined as excessive bleeding from the genital tract at any time following the baby’s birth up to 12 weeks after birth.

If it occurs during the third stage of labour or within 24 hours of delivery, it is termed primary postpartum haemorrhage.

If it occurs during the third stage of labour or within 24 hours of delivery, it is termed primary postpartum haemorrhage.

If it occurs subsequent to the first 24 hours following birth up until the 12th week postpartum, it is termed secondary postpartum haemorrhage.

If it occurs subsequent to the first 24 hours following birth up until the 12th week postpartum, it is termed secondary postpartum haemorrhage.

Primary postpartum haemorrhage

A measured loss that reaches 500 ml or any loss that adversely affects the mother’s condition constitutes a PPH.

There are several reasons why a PPH may occur, including:

Atonic uterus

This is a failure of the myometrium at the placental site to contract and retract, and to compress torn blood vessels and control blood loss by a living ligature action. Causes of atonic uterine action resulting in PPH are listed in Box 19.2.

Box 19.2 Causes of atonic uterine action

• Incomplete separation of the placenta

• Retained cotyledon, placental fragment or membranes

• Prolonged labour resulting in uterine inertia

• Polyhydramnios or multiple pregnancy causing overdistension of uterine muscle

• General anaesthesia, especially halothane or cyclopropane

There are, in addition, a number of factors that do not directly cause a PPH, but do increase the likelihood of excessive bleeding (Box 19.3).

Prophylaxis

During the antenatal period, identify risk factors, e.g. previous obstetric history, anaemia.

During the antenatal period, identify risk factors, e.g. previous obstetric history, anaemia.

During labour, prevent prolonged labour and ketoacidosis.

During labour, prevent prolonged labour and ketoacidosis.

Ensure the mother does not have a full bladder at any stage.

Ensure the mother does not have a full bladder at any stage.

Give prophylactic administration of a uterotonic agent.

Give prophylactic administration of a uterotonic agent.

If a woman is known to have a placenta praevia, keep 2 units of cross-matched blood available.

If a woman is known to have a placenta praevia, keep 2 units of cross-matched blood available.

Management of PPH

Three basic principles of care:

See Figure 19.4 for a summary of management; at the same time as taking these measures, check the blood is clotting.