16 Complicated keratoconjunctivitis sicca

PRESENTING SIGNS

The typical presenting signs of keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS) are well reported and generally the initial diagnosis is straightforward. Thus the dog presented with the slightly sticky mucoid or mucopurulent discharge and conjunctival hyperaemia should always have a Schirmer tear test (STT) performed. Readings of less than 10 mm are diagnostic for KCS but readings between 10 and 15 mm should be considered suspicious, particularly in large breed dogs (an association between higher STT readings in dogs of higher body weight has been demonstrated). Here we will discuss two complications of KCS: acute corneal ulceration and the poorly responsive case. The former will present with a suddenly painful eye – there will not be the increased lacrimation and ‘wet eye’ normally associated with an ulcer since the patient is unable to produce aqueous tears! Instead there will be a copious mucopurulent discharge, sometimes adhered to the cornea such that the patient cannot open its eye. Discomfort will be present and attempts at rubbing the eye are likely.

The presentation of the poorly responsive case of KCS is less dramatic. The dog will probably have been receiving treatment, but the owner might have discontinued this totally or become less meticulous with both medicating and cleaning the eye. Thus the tenacious ocular discharge will have gradually increased, some periorbital disease might have developed or the owner might present the dog again because they have become concerned that its vision has deteriorated.

CASE HISTORY

As outlined above there is typically a previous ocular history. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca has probably already been diagnosed and treatment instigated. However, the condition has not responded as anticipated, or did initially respond such that the owner felt that the dog was better and stopped treatment, and a serious relapse has occurred. The condition is normally bilateral but one eye is often affected more severely and this might be the reason that the owner has returned for a follow-up consultation.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

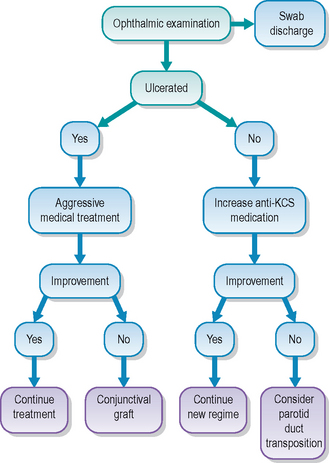

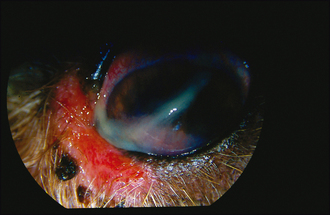

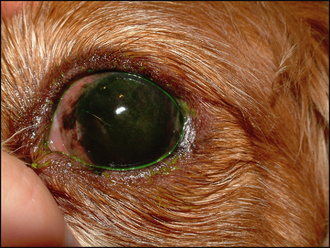

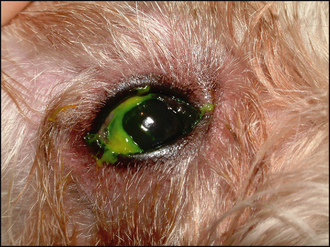

Unless the dog has a systemic disease which can exacerbate KCS, such as diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism or hyperadrenocorticism, general clinical examination is usually unremarkable. On initial ophthalmic assessment the most striking problem is the copious mucopurulent discharge. A sample should be taken for culture and sensitivity before gently wiping this away. Conjunctival hyperaemia and hyperplasia will be apparent. Schirmer tear test readings are expected to be bilaterally low – probably less than 2 mm of wetting in a minute. The periorbital skin might be inflamed and thickened, or even slightly ulcerated if a chronic blepharitis has been present or the patient has self-traumatized (Figure 16.1). The cornea is likely to be pigmented either across the dorsal half or sometimes covering most of its surface (Figure 16.2). Many dogs can still see and retain a menace response despite significant pigmentary keratitis. Branching superficial blood vessels will also be present, and sometimes a slight granulation tissue reaction is also noted, particularly if previous ulceration has occurred. In poorly responsive or neglected cases of chronic KCS ulceration is not always a feature. Once the discharge is cleared away corneal examination will show a dull, lacklustre surface with some epithelial irregularity but not true ulceration. Careful irrigation of excess fluorescein dye is required to prevent false positives as the dye pools in the irregular surface or sticks to the mucus (Figure 16.3).

Figure 16.1 Chronic keratoconjunctivitis sicca in a cocker spaniel with copious mucopurulent discharge and medial canthal blepharitis.

Figure 16.2 Chronic keratoconjunctivitis sicca in 6-year-old Cavalier King Charles spaniel (CKCS). Note the marked corneal pigmentation, vascularization and lacklustre corneal reflection.

Figure 16.3 False-positive fluorescein test due to adherence of the dye to the copious mucoid discharge. This should be cleaned away before checking for ulceration.

Acute ulceration associated with KCS is typically deep and central (Figure 16.4). Thus a facet is clearly visible in the central or subcentral cornea and surrounding corneal oedema can be present. If the secondary bacterial infection is severe then keratomalacia might be present such that the ‘melting’ cornea around the ulcer has a gelatinous appearance. Fluorescein staining will be positive, but it is not uncommon for a descemetocoele to be present such that only the sides of the ulcer retain dye with the central area remaining dark, representing Descemet’s membrane. Some peripheral corneal pigmentation and superficial vascularization might also be noted, reflecting the chronicity of the underlying KCS. A reflex uveitis and miotic pupil might also be noted.

Figure 16.4 Acute severe corneal ulceration in a CKCS. Schirmer tear test readings were 3 mm in this eye and 1 mm in the fellow, non-ulcerated, eye.

The definitive diagnosis of keratoconjunctivitis sicca has already been made. However, other exacerbating factors such as entropion, lagophthalmos, blepharitis and systemic disease might be present and should be considered. A list of the possible causes of KCS is provided in Table 16.1.

Table 16.1 Possible causes for keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS)

| Possible causes for KCS | Comment |

|---|---|

| Immune-mediated lacrimal gland disease (most common) | Most common |

| Congenital lacrimal gland aplasia | E.g. Cavalier King Charles spaniels, Jack Russell terriers |

| Drug suppression of lacrimal gland | E.g. atropine drops |

| Drug toxicity and damage to lacrimal gland | E.g. sulfasalazine and sulphonamides |

| Lacrimal gland adenitis | Distemper virus and some cases of conjunctivitis and blepharitis will have lower Schirmer tear test readings |

| Traumatic injury to lacrimal gland | Road traffic accident with head trauma |

| Neurogenic | Lack of parasympathetic supply to lacrimal glands |

| Other neurological signs sometimes present | |

| Prior removal of nictitans gland | Prolapsed nictitans glands are more common in the same breeds that are predisposed to KCS and gland removal is not recommended |

| Systemic disease | Hypothyroidism, hyperadrenocorticism, diabetes mellitus |

CASE WORK-UP

General clinical examination is important, and should any abnormalities be detected on this, further laboratory tests looking for diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism and hyperadrenocorticism are indicated. All these conditions can exacerbate an underlying KCS and should be considered if the condition had previously been stable on medication but recently deteriorated.

Samples of the discharge should be taken for bacterial culture and sensitivity testing. In addition, conjunctival cytology or even eyelid biopsy in the case of suspected blepharitis might be warranted – particularly if the response to previous medical treatment has been poor.

Specific nursing of complicated cases of keratoconjunctivitis sicca will vary depending on whether ulceration is present or not and whether surgery is indicated. However, careful medical attention is required regardless. Frequent and thorough cleansing of the discharge is required – both to promote patient comfort and to reduce the risk of further secondary bacterial contamination. The eyes should be gently bathed with soft gauze swabs or cotton wool pads soaked in sterile saline before the application of any medication. Since frequent medication is necessary, nurses should ensure that owners are properly able to carry out the treatment at the desired intervals. Patients should be prevented from self-traumatizing – this is most common immediately after the application of topical medication and, as such, the patient should be distracted for a few minutes afterwards.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

There are several causes for KCS in dogs (see Table 16.1) and its incidence is reported at about 1% of the population of dogs presented to North American Veterinary Colleges. Certainly a breed predisposition is noted with immune-mediated KCS, so a presumed inherited component is present, although details of this have not been elucidated, and many other factors are clearly involved. English bulldogs, West Highland white terriers, Cavalier King Charles spaniels, American and English cocker spaniels and pugs are among the many breeds commonly seen with the condition. A sex predisposition to females has been reported in West Highland white terriers.

Although these chronic, insidious, immune-mediated causes are the most common form of KCS seen in practice, various other aetiologies exist. Viral lacrimal gland adenitis occurs with canine distemper infection leading to KCS, which clearly can occur as outbreaks in unvaccinated dogs; congenital hypoplasia of the lacrimal tissue is recognized, sometimes as a unilateral problem in the Cavalier King Charles spaniel and some miniature breeds; drug-induced KCS following systemic sulphonamides, sulfasalazine and topical atropine occurs, and neurogenic KCS due to loss of the parasympathetic innervation to the salivary glands occurs occasionally. Some systemic diseases can also lead to reduced tear production and so patients with diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism and hyperadrenocorticism in particular should have Schirmer tear tests performed regularly.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – MEDICAL

If deep ulceration has occurred, as one of our possible complications to poorly controlled KCS, details of both medical and surgical options are included in the section on complicated ulcers.

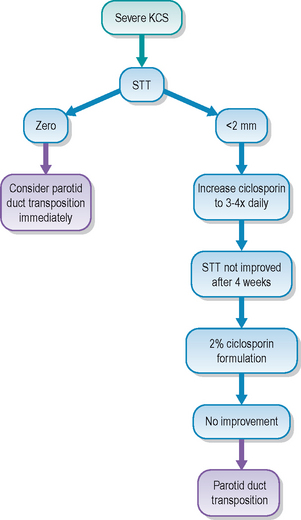

Providing no ulceration is present it is sensible to try to ‘kick start’ tear production in conjunction with controlling the secondary infection and possibly reducing the inflammatory reaction as well. Frequent application of a broad spectrum antibiotic topically, such as chloramphenicol or fusidic acid, is advised pending the results of culture and sensitivity testing. Ciclosporin should be restarted if it had been stopped, or increased in frequency. If Schirmer tear test readings are less than 1 mm of wetting in a minute, then only 50% of cases respond to ciclosporin. Readings of >2 mm generate a response in approximately 80% of cases. Although twice daily administration is the recommended dose, it is sensible to increase this to three or even four times daily in cases which have previously responded then deteriorated and in neglected cases. Clients should be reminded not to apply too much – the size of a large grain of rice is sufficient. Despite the high cost of the drug they tend to apply too much, often with the false assumption that more will increase efficacy. More frequent dosing might, but more ointment will not! Also remember that excessive ciclosporin accumulation on the lid margins can trigger a hypersensitivity reaction and thus blepharitis – if this is present it is important to establish exactly how the owner applies the medication.

In addition to controlling infection, and trying to stimulate increased tear production, more frequent application of topical lubricants is indicated. There are many different formulations available over the counter for people suffering from dry eyes and some people benefit from one type of tear substitute over another. The same is true for our patients and changing lubricant can help. In general, the longer-acting and viscous agents, such as carbomer gel, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose and hylan, are more effective than the traditional polyvinyl alcohol drops. Unfortunately they tend to be more expensive! Ointments such as soft white paraffin are useful at night or if owners are unable to medicate sufficiently frequently during the day.

If, after 4 weeks of increased frequency of application, there is still no improvement in tear production, then it is acceptable to compound a stronger formulation of ciclosporin under the Cascade system. Traditionally, a 2% solution is made by diluting the oral (not intravenous) human formulation in inert corn oil. This is applied two to three times daily and can significantly improve Schirmer tear test readings after 4 weeks. Owners must be made aware that this is an off-licence use of the drug and appropriate forms must be signed. Another recently discovered tear stimulant, tacrolimus, is also effective in poorly responsive cases but is not licensed at all and thus its use is probably best advised only by specialists.

The use of topical anti-inflammatory agents is controversial with refractory KCS. Certainly topical steroids do reduce the conjunctival hyperaemia and hyperplasia along with the corneal vascularization (which subsequently slows the deposition of pigment on the cornea since the blood vessels are the source of the pigment). However, the risk of ulceration is high anyway, and could be exacerbated by long-term topical steroids. The change in commensal bacteria induced by topical steroids can also predispose to more pathogenic bacterial infections. However, the potential benefits can outweigh the potential complications in some patients and their judicious use is sometimes necessary.

If any blepharitis is present, as is often the case with refractory KCS (especially in cocker spaniels!), then systemic antibiotics are indicated. A 2–3 week course of a cephalosporin is usually necessary. If the eyelid margins are very inflamed or ulcerated from self-trauma, a short course of oral corticosteroids (at an anti-inflammatory not immunosuppressive dose) may be beneficial but they should not be used in conjunction with topical steroids due to the high risk of ulceration.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – SURGICAL

If severe corneal ulceration is present, surgical intervention using a pedicle conjunctival graft is indicated as discussed in Case example 23.1 on complicated ulcers and also mentioned in Case example 16.2 below.

In cases with marked pigmentary keratitis, such that vision is impaired, superficial keratectomy to remove the pigmented corneal deposits has been advocated. However, it is not recommended in poorly controlled cases of KCS. Although the surgery is relatively straightforward, removing just the corneal epithelium and anterior stroma, the success is usually short lived. A large, albeit superficial, corneal ulcer is produced by the surgery and its healing is frequently not without complications. Corneal melting, infection, severe vascularization and scarring, and rapid repigmentation all occur. Even in cases of pigmentary keratitis due to other causes (e.g. brachycephalic dogs with lagophthalmos), this surgery is rarely advised, and treatment options aim to reduce the trigger to the pigment deposition rather than removing it after it has formed. Continued use of ciclosporin, even in the absence of increased tear production, can help to reduce the pigment via its anti-inflammatory action.

The main surgical option for non-responsive KCS remains parotid duct transposition. It is interesting to note that the frequency with which this surgery is performed in American Veterinary Colleges has dropped from more than 15% of KCS cases in the late 1970s and early 1980s to less than 2.5% in the late 1990s according to the American Veterinary Medical Data Program. This is mainly due to the advent of ciclosporin and increased earlier recognition of the disease, and clearly is good news for our patients.

However, parotid duct transposition surgery is still indicated in cases with minimal tear production, severe corneal ulceration (as well as surgery for the ulcer) and where frequent medical treatment is not feasible due to owner restraints or a lack of patient compliance. The surgery can be performed in general practice, but since it is no longer routinely required it might be best to consider referral to a specialist who has the necessary expertise and still undertakes this microsurgical procedure with some frequency! It is essential to check that the patient produces saliva normally prior to considering surgery – xerostomia (dry mouth) occasionally accompanies KCS. Placing a bitter substance on the tongue, such as lemon juice or a drop of atropine, should result in copious salivation and on careful inspection drops of saliva can be seen issuing from the parotid duct papilla just above the carnassial tooth on the buccal mucosa. If this does not occur, the patient will not benefit from parotid duct transposition surgery.

Owners need to be carefully informed of the reason for choosing the surgery and the potential complications which can occur. It is a salvage procedure for the eyes and although it is often very successful and of great benefit to the patient, it can be a bit of a poisoned chalice on occasion. Normally the surgery is successful in that the eye becomes wet with saliva almost immediately. However, saliva contains a much higher mineral concentration than tears, and salty deposits can accumulate both on the eyelids and the cornea itself. These are often benign but some patients become uncomfortable and require removal either with EDTA drops or even superficial keratectomy. Lubricants to soothe the irritation can also help (soft liquid paraffin ointment for example). Bacterial infections can occur more commonly than in normal eyes – the usual conjunctival flora is changed considerably following surgery – and owners should be made aware that if there is any change in the nature of the discharge or patient comfort they should present the patient at the surgery.

Another potential problem following parotid duct transposition is epiphora – the degree of salivation into the eye cannot be controlled and in some dogs is excessive such that they have permanent tear overflow and resultant moist dermatitis on the face. This can be a particular problem in the ‘slobbery’ breeds such as Neapolitan mastiffs, such that surgery might even be contraindicated. Many dogs will ‘cry’ when fed or if food is being prepared, but providing this is not excessive it is an acceptable alternative to end-stage KCS.

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis for complicated KCS is somewhat guarded in a number of cases. If severe ulceration has developed, then both conjunctival grafting and parotid duct transposition might be indicated (sometimes at the same time) but even after this the eye will never be ‘normal’. Occasionally enucleation is necessary. With chronic pigmentation vision can be impaired and even following parotid duct transposition complications with irritation and blepharitis from mineral deposition are not uncommon. Thus early diagnosis and regular monitoring, with good owner and patient compliance, are required to prevent such complications.

The patient had a long history of keratoconjunctivitis sicca affecting both eyes, which had initially been diagnosed 3 years previously. It had been well controlled on twice daily ciclosporin and carbomer gel, and once daily soft liquid paraffin ointment at night. Schirmer tear test had been between 8 and 14 mm in each eye. However, 2 weeks before presentation the left eye started to discharge more, and the dog was unable to open its eye in the morning. The owner increased the frequency of carbomer gel to four times daily but little improvement occurred and so she presented the dog. He was also hypothyroid but this was well controlled with levothyroxine sodium.

CLINICAL SIGNS

General clinical examination was unremarkable apart from a slightly dry, scurfy coat. On ophthalmic examination a sticky mucopurulent discharge was present in the left eye, adherent to the cornea (Figure 16.7). Severe superficial corneal vascularization and pigment deposition were also noted. Schirmer tear test readings were 3 mm/min in the left eye and 11 mm/min in the right. Menace responses and pupillary light reflexes were normal and intraocular examination, although limited, showed no gross abnormalities. A swab was taken from the discharge before it was cleaned away and the cornea stained with fluorescein. This revealed no ulceration.

WORK-UP

The swab was submitted for bacterial culture and sensitivity, and showed a profuse growth of coagulase-positive Staphylococcus spp. with moderate resistance to fusidic acid and ciprofloxacin, although it was sensitive to chloramphenicol. Thyroid function was checked and found to be satisfactory.

TREATMENT AND OUTCOME

The ciclosporin was increased to four times daily in the left eye, and chloramphenicol drops were started at the same frequency. Topical carbomer gel was applied every 3 hours during the day and the soft white paraffin continued at night. After a week the discharge had reduced but tear production was still only 5 mm/min and significant conjunctival hyperaemia remained. It was decided that anti-inflammatory medication was required, but the use of topical steroids was not advised given the risk of ulceration and so prednisolone was started at 0.5 mg/kg/day for 5 days then every other day for 10 days. The topical medication continued. The eye improved well, with Schirmer tear test readings of 10 mm in the left and 12 mm in the right after 3 weeks. The treatment was then continued with ciclosporin three times in the left (still twice in the right) and lubricants four times daily. After another month tear production was 14 mm in the left and the ciclosporin was reduced to twice daily.

This example illustrates that controlled cases of keratoconjunctivitis sicca can wax and wane such that the medication needs to be adjusted. The dog clearly developed a bacterial infection but it is difficult to know if this was the reason for the reduction in tear production or a result of it. Tear production remained low despite apparently controlling the infection, which suggested some lacrimal gland adenitis. The systemic steroids appeared to settle this and tear production returned to the pre-infection levels.

The dog had a 1-year history of bilateral KCS which was controlled on the standard medication of twice daily ciclosporin only. Tear production had increased from 8 mm/min to 16 mm/min (similar in both eyes) and no problems were reported. However, suddenly the right eye started to discharge excessively and the dog cried out when the owner tried to clean the eye. They started using some chloramphenicol drops twice daily which they had in the house. They presented the dog 5 days later.

CLINICAL SIGNS

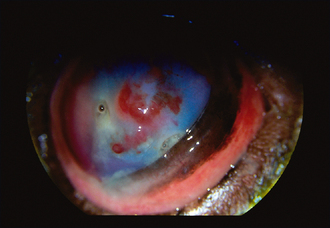

The dog was slightly depressed but otherwise clinically unremarkable. The right eye was closed and the dog shied away and cried when attempts were made to examine it. A copious mucopurulent ocular discharge was present. Schirmer tear test readings were 8 mm/min in the right and 4 mm/min in the left. The latter had mild corneal vascularization and conjunctival hyperplasia typical of chronic KCS. After gently cleaning the right eye the severe corneal pathology became apparent. Marked corneal oedema and vascularization were present with what appeared to be intrastromal haemorrhage. A ventrolateral ruptured corneal ulcer was present, along with a deep ulcer more medially which was obscured by the third eyelid (Figure 16.8). A dazzle response was present but no menace response and a pupillary light reflex could not be assessed, although there was a consensual constriction of the left pupil when light was shone in the right.

WORK-UP

A swab was taken from the discharge but no significant growth was detected. It is difficult to know if this was as a result of the previous usage of chloramphenicol drops, although twice daily is a suboptimal level to achieve the bacteriostatic effect. The owners were given the option of attempting to salvage the eye or enucleation and opted for the former, and referral for this was arranged. Parotid duct transposition was discussed but the owners were reluctant to have this procedure as well. Pre-anaesthetic blood tests were unremarkable.

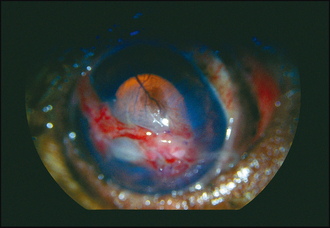

TREATMENT

Under general anaesthesia the corneal ulcers were repaired using a long conjunctival pedicle graft sutured into the two ulcers (Figure 16.9). Postoperative medication was intensive (see Table 16.2) and continued for 2 weeks before reducing to just ciclosporin three times daily and frequent lubrication. Ciclosporin was increased to three times daily in the left at the time of surgery since tear production was also reduced in this eye.

Table 16.2 Postoperative medical treatment for Case example 16.2

| Drug | Frequency | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Ciclosporin | 4× | Try to stimulate increased tearing |

| Ciprofloxacin | 6× | Treat any infection (in spite of non-diagnostic swab) |

| Tropicamide | 3× | Mydriasis to reduce reflex uveitis |

| Carbomer gel | 6× | Topical lubrication |

| Cefalexin | 125 mg twice daily | Reduce risk of secondary infection |

| Carprofen | 20 mg twice daily | Analgesia and anti-inflammatory |

OUTCOME

The dog did very well. Four weeks later the graft was incorporated into the cornea and the oedema and vascularization had reduced dramatically. Vision was good. The discharge was also minimal and tear production was back to 10 mm in the right and 8 mm in the left. The dog was continued on ciclosporin three times daily for another 2 months, at which time tear production was 13 mm in the right and 12 mm in the left, and it was reduced to twice daily again.

This case illustrates the sudden deterioration which occurs if ulceration develops. The dog could easily have lost the eye. If tear production had not improved again then parotid duct transposition would have been advised. The owners are aware that the left eye could ulcerate and check the dog very carefully.