23 Complicated corneal ulcer

The previous two case descriptions illustrate very com-mon presentations in general practice – the superficial non-healing ulcer and the deep ulcer. The treatment plan outlines ways to treat these conditions but assumes that everything goes well. In this chapter we will discuss the ulcer that does not heal according to plan.

PRESENTING SIGNS

It is likely that the animal has already been presented for treatment, although some cases might have been present for a while before the owner brings the pet along to the surgery – the cat might have been missing for a few days for example. The animal may have been taken to another surgery, the owners could have failed to return when asked, or – in spite of everything being followed correctly – things could have taken a turn for the worse. As such, the presentation will be of a painful eye. The animal is likely to be holding the affected eye closed and it is likely that significant ocular discharge will be noted – most probably mucopurulent in nature.

CASE HISTORY

It is usual for the history to include the suggestion of trauma – the cat comes back early one morning with one eye closed for example, although this is not true in 100% of cases. On initial presentation a corneal ulcer will have been diagnosed which was treated symptomatically with a broad spectrum topical antibiotic. A few days’ improvement may be reported before the eye deteriorated – it became more painful, changed in appearance to the owner or the discharge altered and became more copious. The patient may have had surgery already – for example, a third eyelid flap which on removal revealed a nasty corneal lesion.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

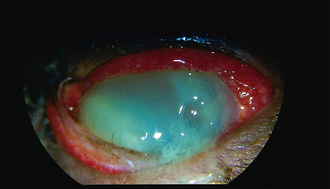

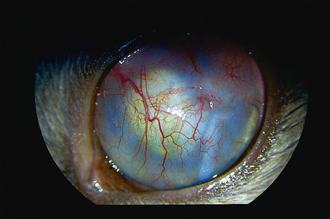

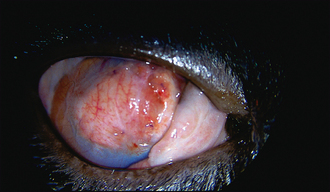

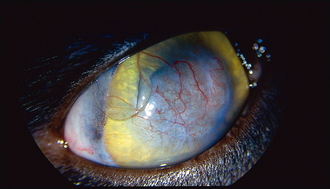

The ulcer should be obvious on clinical examination. However, the conjunctiva is likely to be hyperaemic, the nictitans membrane elevated and chemosis might also be present which could make visualization of the cornea difficult (Figure 23.1). Sometimes the ocular discharge will be extensive such that the eye is ‘glued’ shut. Gently bathing this away (and taking swabs for culture and sensitivity at the same time – but see below) will assist in examination. Overt ulceration might not initially be visible – there is likely to be significant vascularization (even granulation tissue) on the cornea, along with oedema, both of which obscure the actual ulcer. If areas of cornea appear gelatinous, and creamy or grey in colour, this could suggest keratomalacia or corneal melting (Figure 23.2).

Figure 23.1 Nasty corneal ulcer in a cat – notice the abundant granulation tissue, more medial ulcer and vascularization, chemosis, nictitans elevation and copious discharge.

Figure 23.2 Melting ulcer in a cat – note the overall gelatinous appearance to the cornea and general opacity. The darker central area is the site of the original ulcer. Atropine has partially dilated the pupil, which looks distorted due to the abnormal corneal curvature. A copious discharge is also present and a hair is adhered to the cornea.

To make it easier to examine a painful cornea, the patient should be placed at the end of the consulting table and made to look down, while you look up from below. This usually makes it possible to view most of the cornea as the nictitans membrane moves into the ventromedial fornix. The use of topical anaesthesia, and even sedation or general anaesthesia, might be necessary to fully evaluate the eye in some patients.

CASE WORK-UP

It is essential that swabs are taken for culture and sensitivity testing from all potentially infected corneal ulcers. These can be taken before topical anaesthesia. Samples can be collected from the ocular discharge but more accurate isolation will be obtained from the ulcer edge itself – a bacterial swab moistened with sterile saline can be gently rolled onto the edge of the ulcer. This can also be used to perform Gram staining (by then rolling the swab onto a microscope slide and staining it appropriately). Cytology should also be considered – samples collected by swabs do not yield high numbers of cells and so the use of a cytobrush or Kimura spatula (or the blunt end of a scalpel blade) is preferred. Topical anaesthesia is necessary before such sampling. Samples should be spread onto a microscope slide and air dried. Staining with Diff-Quick or similar stains can be useful to look for the presence of bacteria, the type and number of cells (usually a combination of neutrophils and degenerate keratocytes in a bacterial infection) and the presence of inclusion bodies (for example, with Chlamydophila). The presence of fungal elements should be considered – although relatively rare in the UK, these can have devastating consequences if not identified and treated accordingly.

The eye should be fully examined for the evidence of anything that could be contributing to the poor healing, or exacerbating the ulcer. Retained foreign bodies and abnormal cilia are probably the most common culprits after bacterial infection.

The specific nursing for complicated corneal ulcers is similar to those for deep ulcers (see Chapter 22). Thus regular bathing of any discharge and the frequent application of topical medication are necessary. It is also important to alert the attending veterinary surgeon to any change in the condition of the patient, both of the eye itself and of the animal’s general demeanour – a sudden deterioration could require urgent surgical intervention.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The complication of bacterial infection is the most common cause of ulcer progression. The conjunctival sac normally carries a mixed population of mainly Gram-positive bacteria (e.g. staphylococci, streptococci and corynebacteria). These can act as opportunist pathogens once the corneal epithelium is breached. However, infection with more pathogenic organisms, mainly Gram-negative bacteria (e.g. Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas), is likely in more severe ulcers. Mycotic infections do occur occasionally in the UK but are common in some parts of the world. Cytology is important for their diagnosis initially, followed by culture to identify the exact fungus. Candida albicans and Aspergillus spp. are reportedly the most frequent isolates in the UK.

Not all complicated ulcers are infected. Sometimes degenerating keratocytes or neutrophils can release collagenases which cause further corneal damage. Clearly if other pathological processes are occurring in the eye simultaneously – uveitis or glaucoma for example – the risk of complications with an ulcer is higher.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – MANAGEMENT

The owner should be fully apprised of the severity of the condition from the outset. A treatment plan should be drawn up and followed. Obviously this must be tailored to the individual and will include factors such as patient compliance, owner finances and commitment, as well as the condition of the eye itself.

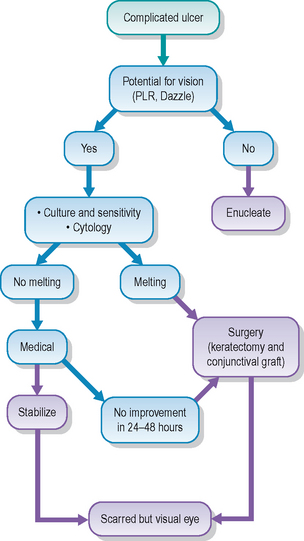

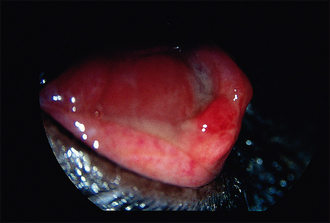

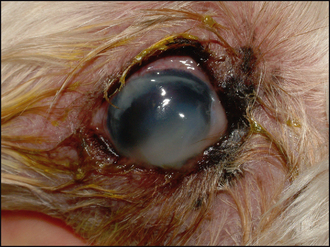

The first decision to be made should be: Is the eye salvageable? In some cases the cornea will be so severely compromised that the ulcer has ruptured, the iris has prolapsed and a panophthalmitis has resulted (Figure 23.3). If this is the case, then enucleation might be the best option for the patient. However, this is an irreversible decision and so one should be convinced that there is no alternative. If the eye has the potential for vision, enucleation is not advised. A positive dazzle response, together with a consensual pupillary light reflex (i.e. constriction of the fellow eye when a bright light is shone into the affected eye), are encouraging signs. If neither is present, then removing the eye might be indicated. If you are not sure whether the eye can be saved, referral should be considered. The welfare of the patient is paramount.

Figure 23.3 Six-month-old Boston terrier. A deep corneal ulcer has received a conjunctival graft. Unfortunately, this did not hold and the ulcer continued to deepen, resulting in keratomalacia and iris prolapse as the cornea ruptured. A profuse growth of Pseudomonas, resistant to gentamicin (which the dog had been treated with), was isolated but by this time enucleation was the only option.

In order to achieve healing some patients might require very frequent topical medication (every 1–2 hours) over several days, followed by ongoing medication for several weeks, often in conjunction with one or more surgical procedures. If the patient is very nervous, or aggressive, then such intensive medication might be difficult for owners and professionals alike, as well as being traumatic for the patient.

If the final outcome is a very scarred cornea, such that vision is severely limited in the affected eye, one needs to evaluate the case very carefully before deciding whether to try to save the eye. Having said that, it is amazing how well some cases can do (see Case example 23.1 below). Thus it is often sensible to attempt treatment initially, ensuring that the owner is fully informed of the situation, and is aware that the eye might require removal if an improvement is not seen within a few days.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – MEDICAL

The medical management of infected ulcers is intensive (see Table 23.1). It will revolve around appropriate antimicrobial drugs. Gram staining is important to assist the choice of medication while awaiting the results of culture and sensitivity testing. Since Gram-negative pathogens are commonly isolated, a suitable choice of topical antibiotic could be gentamicin or tobramycin. Both have good activity against agents such as Pseudomonas although resistant strains are encountered. If Gram-positive organisms are identified, then a fluoroquinolone antibiotic such as ciprofloxacin or ofloxacin might be more appropriate. Both gentamicin and ciprofloxacin can be used alternately pending sensitivity results. Initial topical application should be every 2–3 hours. Subconjunctival injections of gentamicin or a cephalosporin can also be considered.

Table 23.1 Medial management of complicated ulcers

| Agent | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Topical antibiotic chosen on Gram stain: | Every 1–2 hours (over 24-hour clock – do not stop at night!) |

In addition to antibiotic cover, topical atropine is usually recommended to reduce the ciliary spasm encountered with severe corneal disease. It will also help to stabilize the blood–aqueous barrier and reduce the severity of a concomitant uveitis. Atropine should be used to effect, i.e. frequently enough to keep the pupil dilated. This is usually two or three times daily. Atropine should not be used in cases of keratoconjunctivitis sicca since it lowers tear production even further. Cats do not tolerate the drops well, and so an ointment formulation might be more appropriate.

Medical management can also consider the use of autogenous serum. This is particularly useful in the case of keratomalacia, i.e. melting ulcers. Here a combination of collagenase activity – both exogenous (from the bacteria) and endogenous (from degenerating keratocytes and neutrophils) – contributes to liquefaction of the corneal cells. Untreated this will lead to complete corneal dissolution and loss of the eye. Hourly serum can arrest such melting by providing protease inhibitors to the cornea. Blood is taken from the patient and spun down. The serum is placed in a sterile container and kept in the fridge. It should not be used for more than 48 hours and is not suitable for home medication (owners are unlikely to follow a strict aseptic technique and serum is the perfect culture medium for bacteria!). Alternatives to autogenous serum include acetylcysteine and EDTA.

Topical NSAIDs are sometimes used if a severe uveitis is also present. However, systemic agents are normally given, and often will be sufficient. A broad spectrum antibiotic such as a cephalosporin should also be administered.

If the ulcer has not stabilized after 24–48 hours then surgical intervention should be considered. It might be necessary to refer the patient at this stage. Encouraging signs will be a reasonable vascular reaction approaching the ulcer edge, a less gelatinous appearance to the cornea (especially the area immediately adjacent to the actual ulcer) and a shallowing of the ulcer itself. Less discharge should be present and the animal should be more comfortable (Table 23.2). However, if the ulcer seems to be getting deeper despite the intensive treatment regimen, or the cornea is becoming more jelly-like, then surgery is indicated.

Table 23.2 Good and bad signs in ulcer appearance

| Good signs | Bad signs |

|---|---|

Figures 23.4 and 23.5 show a Pseudomonas-positive melting ulcer in a domestic short haired cat on presentation and 4 weeks later after 2 weeks of hospitalization and intensive medication, followed by a fairly intensive home regimen. Surgery was not required and the eye was salvaged with reasonable vision. However, the treatment was very intensive which was only possible due to the cat’s good temperament and the owner’s determination not to give up!

TREATMENT OPTIONS – SURGICAL

The surgical management of complicated ulcers rests with the removal of infected or unstable corneal tissue followed by support of the weakened structure. Thus keratectomy with grafting (usually conjunctival rather than corneoscleral transposition) is required, and suitable experience and equipment are necessary for this. Referral might be appropriate. The keratectomy will result in small pieces of cornea which can be submitted for histopathology and culture. This is important even if cytology and bacterial culture have already been performed – there could have been a change in pathology at the ulcer site (which could explain why medical treatment was not successful) or the isolates might have been from the conjunctival fornix and not the ulcer at all.

Conjunctival grafts will support the weakened corneal stroma while bringing a blood supply directly to the damaged tissue. They are preferred over corneoscleral transposition if keratomalacia is present since the corneal melting can continue into the newly transplanted tissue and result in surgical failure. Grafts using porcine submucosa material (BIOSIS) also run the risk of rejection. Sutures are usually 8/0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl, Ethicon) but it must be remembered that as multifilament material the risk of infection tracking into the suture sites is slightly greater than if a monofilament material is chosen.

Postoperative medication will be similar as for the medical treatment options above. Frequent topical medication will be required still, as well as atropine and systemic antibiotics and NSAIDs. Topical serum should not be necessary as the graft should be providing nutrients including anticollagenases.

Once the cornea is fully healed, usually in 3–4 weeks, the conjunctival graft can be trimmed. This will leave a small area adhered to the cornea while the surrounding tissue should clear well, such that good vision is restored.

The use of third eyelid flaps is not recommended for infected or progressing corneal ulcers. They do not provide any direct support to the ulcerated cornea, they reduce the penetration of topical medication and totally obscure the cornea such that frequent monitoring of the underlying lesion is not possible. It is not uncommon for ulcers to progress under the flap: it is warm and moist under a flap – ideal conditions for continued bacterial infection – with the added disadvantage that discharges are not removed but left to accumulate between the cornea and third eyelid, thus contributing to further corneal damage. Undoing a third eyelid flap to discover that the ulcer has ruptured occurs on occasion such that enucleation is then the only treatment option.

PROGNOSIS

Owners should always be given a guarded prognosis for complicated ulcers. However, if an underlying reason for the complication – such as a previously undetected ectopic cilium or fragment of grass seed – is identified, the prognosis obviously improves once this has been removed. If the ulcer is stabilized and responds to treatment, the owners should be aware of the realistic expected outcome. This is a scarred, but visual eye. They should not expect the eye to return to complete normalcy.

The cat was presented as a second opinion because the owners were very concerned about the lack of improvement in the cat’s eye. It had been diagnosed with a corneal ulcer a month previously, after having been absent from home for 3 days. It was initially treated with chloramphenicol drops three times daily but a week later the eye was still red, sore and discharging and a third eyelid flap was placed. On removal 2 weeks later the eye looked dreadful and enucleation was advised. The owners declined and sought specialist advice.

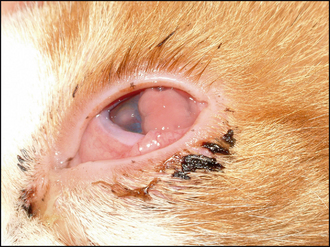

CLINICAL SIGNS

The right eye was totally red on presentation and blind with no menace response although a dazzle reflex was present but no consensual light reflex in the left when light was shone in the right. Closer examination (Figure 23.7) revealed severe central granulation tissue with peripheral corneal ulceration and melting dorsomedially. The bulbar surface of the nictitans membrane was partially adhered to the granulated cornea. Intraocular examination was impossible.

WORK-UP

Samples were taken for Gram staining (revealing mostly Gram-positive organisms) and culture and sensitivity testing (mixed staphylococci and streptococci with good sensitivity). The owner was adamant that the eye should not be removed. Ultrasonography was performed under sedation and the anterior chamber appeared formed with no corneal rupture. Some debris was present in the anterior chamber (blood or hypopyon). Since the eye appeared viable surgery was scheduled.

TREATMENT

Under general anaesthesia the adhesions between nictitans membrane and cornea were broken down. The cornea was debrided and an island conjunctival graft sutured into place covering the ulcerated cornea. The graft had been harvested from the fellow eye since the right eye contained no normal conjunctiva. Topical ciprofloxacin every 2 hours and three times daily atropine ointment were dispensed, along with systemic cefalexin and 48 hours of buprenorphine injections.

OUTCOME

A week later the graft was vascularized and viable. Ciprofloxacin was reduced to four times daily and atropine once daily.

Three weeks later the graft was still healthy. No ulceration was present and treatment was changed to neomycin, polymyxin B and dexamethasone drops (Maxitrol, Alcon) four times daily (Figure 23.8).

Ten weeks after surgery the eye was comfortable and visual. The corneal vascularization continued to clear but the cat needed to stay on once-daily steroid drops to keep the inflammatory reaction at bay (Figure 23.9).

This case illustrates the amazing healing capacity some cats possess! Enucleation appeared to be a sensible option at initial presentation but with complicated surgery and intensive after-care, together with very dedicated owners, the cat not only retained its eye but also regained good vision.

The patient suffered from diabetes mellitus and developed sudden onset cataracts secondary to this. She did not cope with the blindness and underwent cataract surgery on the right eye. Initially this did very well, and vision was good. However, 6 weeks after surgery the owner noticed that the eye became cloudy and started to discharge. She had an appointment with the ophthalmologist the following week so continued with the eye drops that the dog was on at the time (prednisolone acetate and tropicamide both twice daily). The eye continued to deteriorate.

CLINICAL SIGNS

On presentation vision was very limited. The conjunctiva was inflamed and the eye was painful. The corneal wound was grey with an irregular cornea while a large area of corneal melting was present ventrally, resulting in keratoconus (Figure 23.10).

WORK-UP

Swabs were taken from the ocular discharge and the gelatinous part of the cornea (which appeared very unstable). No bacterial growth was isolated, nor were any bacteria observed on an initial Gram stain. Blood glucose samples were taken regularly to monitor diabetic control.

TREATMENT AND OUTCOME

Intensive medical treatment was started – ciprofloxacin every 2 hours, hourly autogenous serum, atropine drops and ketorolac drops every 6 hours, plus systemic methadone, carprofen and cefalexin.

Twenty-four hours later the cornea appeared to be stabilizing – the ventrally melting cornea was more ‘firm’ and no further keratomalacia was noted. Medication was continued. Five days later the corneal ‘melt’ came off as the eye was bathed. Ulceration was still present but this seemed superficial. Marked hypopyon was noted (Figure 23.11). The eye was blind. Ultrasonography under sedation revealed a total bullous retinal detachment and significant vitreal debris. The owner was warned that vision would not return and was given the option of continued intensive medical management to salvage the eye, or enucleation. Since the dog was still in discomfort, and did not tolerate hospitalization well, enucleation was performed. Histopathology was unfortunately not performed.

Figure 23.11 Same patient as in Figure 23.10, 5 days later. Although the cornea is stabilizing, a severe uveitis is present with marked hypopyon.

This case illustrates how although the cornea might be starting to improve other serious consequences can occur in the eye. The owner should have presented the dog immediately on noticing a change in the eye (she did have written instructions to this effect!) but instead continued using topical steroids. The cornea was probably ulcerated for several days (ulceration following cataract surgery is always a risk, but occurs more commonly in diabetic patients). The keratomalacia will have been enhanced by the steroids. The previous intraocular surgery and severe corneal disease both resulted in destabilization of the blood–aqueous barrier and a severe panuveitis developed, resulting in retinal detachment. Unfortunately, enucleation was the only sensible option left.