22 Deep corneal ulcer

PRESENTING SIGNS

Both dogs and cats can present with deep corneal ulcers. Usually the owner will notice a painful eye – blepharospasm and conjunctival hyperaemia (the ‘red’ eye). Some form of ocular discharge is inevitable. This might be purely serous and present as a very wet eye, but is often mucopurulent or purely purulent in nature. The latter is particularly a feature if the owner has failed to bring the pet into the surgery immediately – deep ulcers can be complicated by bacterial infection quite commonly. The pet might have been seen to rub the eye frequently as well.

CASE HISTORY

In most cases the presentation of a deep corneal ulcer is acute in nature. The owner might have been out walking the dog in the woods and it came back with one eye closed and weeping for example. Or the cat was heard to be fighting with a neighbouring tomcat, resulting in a deep corneal scratch. Thus a history of a possible traumatic episode is very common. However, on occasion, there is no such trigger factor in the history and in these cases it is important to check the patient very carefully for other possible causes – an ectopic cilium for example.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

Obviously a full clinical examination should be performed as well as concentrating on the eyes. This is particularly important if a traumatic injury is suspected. The affected eye is likely to be partially closed with the third eyelid protruding. This can make detailed examination difficult, especially if chemosis is also present (more common in cats – the conjunctival swelling can be so dramatic as to render corneal examination almost impossible). Sedation is sometimes necessary to fully evaluate the cornea, but before rushing to do this a few things can be done to improve your examination:

The ophthalmic examination should include measuring aqueous tear production. If the eye is very painful, or the ulcer is very deep and you are concerned about corneal rupture, then perform the Schirmer tear test on the fellow eye only. Acute keratoconjunctivitis sicca is an under-recognized cause of sudden onset, deep corneal ulceration in the dog (see Case example 16.2). The eye is assessed for vision, and the pupil should be checked – often some miosis is present representing a reflex uveitis and this should be addressed when formulating a treatment plan. A frank uveitis with aqueous flare or even hypopyon can be present in conjunction with deep corneal ulceration, especially if bacterial infection is present. Careful evaluation of the conjunctival sac, including behind the third eyelid, should be undertaken since foreign bodies can be retained here. Intrinsic factors causing the ulcer, such as ectopic cilia or entropion, should also be looked for (Figure 22.1).

Figure 22.1 Nasty granulating corneal ulcer associated with a large distichium on the upper eyelid. Although it is uncommon for distichia to cause ulceration, if the lash is directed straight onto the cornea and rubbing, then ulcers do sometimes arise.

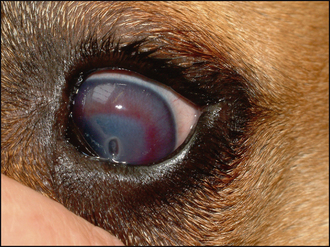

The ulcer is usually obvious as a defect or crater in the cornea (Figure 22.2). It can be assessed for depth both before and after staining with fluorescein. It is important to flush out excess dye with sterile saline to prevent pooling in the defect which can confuse the interpretation of the test. The exposed stroma will retain fluorescein, while Descemet’s membrane does not. Thus a deep ulcer which does not stain is likely to suggest a descemetocoele which should be treated as an ocular emergency. If the ulcer is actually healing, then the bottom of the lesion might not take up dye if the epithelium has fully covered all the stroma. The stromal edges are likely to be more gently sloped toward the depth of the lesion rather than being almost vertical when recently ulcerated.

Figure 22.2 Acute ulceration in an English bulldog with keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Note the two-step crater – the deeper portion looks dark and represents a descemetocoele.

The depth of the ulcer is important when formulating a treatment plan. Also of importance is the presence or absence of blood vessels. These grow from the limbus towards the damaged cornea at the rate of about 1 mm per day. This can be used to determine the length of time the lesion has been present. If the blood vessels are getting close to the ulcer, then medical management might be a feasible option. Some corneal oedema is often present around deep corneal ulcers so a grey ring to the lesion is commonly seen. This should be differentiated from the keratomalacia seen in melting ulcers (see Case example 23.2). In this instance the cornea will be grey and gelatinous in appearance, and when examined from the side the outline of the cornea will be distorted (keratoconus). Blinking and tear film distribution should be evaluated in all cases of deep corneal ulcer. Brachycephalic breeds often have some degree of lagoph-thalmos, and corneal exposure combined with poor or incomplete blinking can compromise healing.

CASE WORK-UP

Only limited case work-up is usually required for deep corneal ulcers since the diagnosis is easily made on ophthalmic examination, and unless multiple trauma has occurred (e.g. dog fights or road traffic accidents), further systemic evaluation is not normally required. As mentioned in the section above on the clinical examination, Schirmer tear test readings should always be taken. This is particularly important if a central descemetocoele is present since acute keratoconjunctivitis sicca is an important, and often forgotten, cause for these (see Chapter 16). If there is a mucopurulent or purulent ocular discharge, a swab should be taken for bacterial culture and sensitivity. Samples for cytology should also be considered. Treatment plans can be drawn up once the specific cause of the ulcer is identified.

The treatment for corneal ulceration can be medical, surgical or a combination of both. Nursing care will be required. Frequent topical medication is usually necessary, using drops, ointments or sometimes both. Drops should always be applied before ointments if both are employed, and a minimum of 5 minutes (but ideally 10–15) should be left between different topical applications. Nurses should gently bathe any discharge from the eye using soft woven gauze swabs (not cotton wool which can shed fibres) and sterile saline. Patients should be evaluated for signs of discomfort and the veterinary surgeon in charge of the case should be informed of any change in patient comfort such that appropriate analgesia can be prescribed. Self-trauma and rubbing (either with the paws or against the bedding for example) must be avoided. By making the patient comfortable this can usually be prevented and Elizabethan collars are not always required routinely – providing proper monitoring is undertaken.

If surgical treatment is planned, the nurse will be involved in preparing the patient, including anaesthesia and surgical preparation of the eye along with liaison with the surgeon regarding the instruments and other surgical equipment necessary for the procedure. Postoperative nursing instructions, both for the time the patient is hospitalized and afterwards for the owners, should be considered.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The cause for deep corneal ulcers is usually evident from the clinical examination. Traumatic incidents are common but progression from a superficial ulcer is also frequent – especially if bacterial contamination has occurred and if the owner has delayed seeking veterinary attention. Ulcers of this sort tend to occur on an individual basis – pathogens are usually opportunistic and contaminate the injury rather than being primary corneal pathogens with infectious spread between animals. Thus Gram-positive bacteria are usually present initially but Gram-negative ones such as Pseudomonas can become involved. Fungal infectious are rare in the UK but should be considered if the ulcer is not responding to conventional therapy.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – MEDICAL

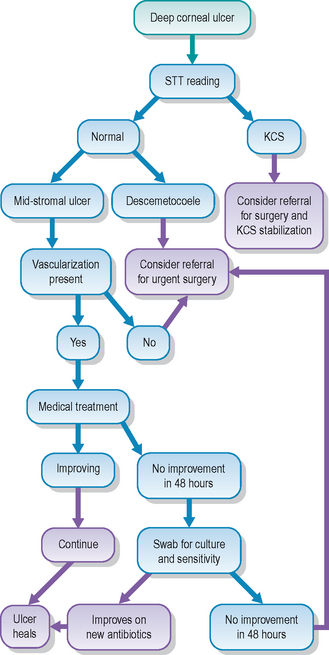

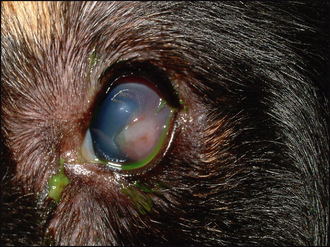

If the ulcer is deep, but not down to Descemet’s membrane, and there is evidence of corneal vascularization, then medical management is an option (Figure 22.3). However, if a descemetocoele is present, then the eye is in danger of imminent rupture and surgery must be recommended. Similarly, if the patient is suffering from acute keratoconjunctivitis sicca as the underlying cause for the ulcer, then surgical procedures, in addition to addressing the lack of tear production, are usually necessary.

Figure 22.3 Deep corneal ulcer (descemetocoele) in a 4-year-old terrier. Although this is a deep ulcer, there is good corneal vascularization and this can be treated medically to achieve healing.

For medical management a combination of both topical and systemic medication is normally necessary (Table 22.1). The frequent application of topical antibiotics is required. These should be chosen according to the likely pathogens involved. The conjunctival sac normally contains mainly Gram-positive bacteria (such as staphylococci and streptococci) and these tend to be the most frequent opportunistic pathogens. Antibiotics such as fusidic acid and chloramphenicol are good choices, and are licensed for use in dogs and cats. Gentamicin can be used, particularly if the cornea has any grey, melting appearance, which could suggest a Pseudomonas infection. Swabs should always be considered, and if the ulcer has not responded favourably after a few days, then culture and sensitivity testing is a very good idea, particularly if one is considering changing the antibiotics. The frequency of application will depend on the degree of infection suspected and the formulation of the drug. Sometimes as often as hourly is required. Fortified antibiotic solutions are occasionally used – for example, an intravenous formulation of a cephalosporin can be placed into artificial tears and used at a much higher concentration than is available commercially. Potent topical antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin and enrofloxacin should not be used as first-line antibiotics but are useful in infected cases while awaiting culture and sensitivity results.

Table 22.1 Medical management of uncomplicated deep corneal ulcers

| Agent | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Topical antibiotic, e.g. chloramphenicol, gentamicin (or chosen according to culture and sensitivity testing) | Four to eight times daily |

| Topical atropine | Twice daily (or less – to effect) |

| Systemic NSAID | Once or twice daily |

| Topical NSAID | Two to three times daily – only necessary if overt uveitis is present |

| Autologous serum | Hourly if corneal melting occurs – consider referral for surgery |

In addition to topical antibiotics, topical atropine is usually advised to relieve the ciliary spasm associated with reflex uveitis and to help stabilize the blood–aqueous barrier, thus reducing further uveitis. It should not be used in keratoconjunctivitis sicca (since it lowers tear production even further – tropicamide can be used instead although more frequent application will be required). The atropine should be used to effect, i.e. to keep the pupil moderately dilated. Initially this might be twice daily, reducing to once, or even every other day. Remember that the drops drain down the nasolacrimal duct and taste bitter so might make patients dribble and salivate excessively – especially cats where ointment formulations are preferred.

Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents are sometimes used for deep ulcers. They should only be chosen if an active uveitis is present (but not with frank hyphaema). If the pupil dilates readily with atropine then they are probably not required. They will slow corneal vascularization which can lead to a delay in healing. The use of systemic NSAIDS is probably preferred in many instances.

Autologous serum is used topically for deep corneal ulcers which show a tendency to melt. It contains anticollagenases which reduce the keratomalacia that can result from the excessive collagenase activity of neutrophils, bacteria or degenerating keratocytes. Blood is collected from the patient, spun down, and the serum dropped into the eye on a 1–2 hourly basis. The serum should be handled in an aseptic manner and kept in the fridge. Fresh supplies should be collected every 24–48 hours. If the ulcer is so severe as to warrant its use, it is probably wise to hospitalize the patient – progression rather than improvement might require emergency surgery to prevent corneal rupture. Serum is not beneficial in uncomplicated deep ulcers.

Systemic medication takes the form of NSAIDs and sometimes a broad spectrum antibiotic such as a cephalosporin or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (particularly if frequent topical medication is not feasible although systemic medication is less effective).

Improvement in the ulcer will manifest as a shallowing of the crater – the edges will become more sloping, rather than vertical, as the epithelium slides into the defect. The blood vessels will grow towards the edge of the lesion, and once they reach it the defect will epithelialize quickly. At this stage the frequency of topical application can be reduced. Once fluorescein is not retained the ulcer can be said to have healed, but a stromal facet will remain and it can take weeks for this to infill. As such, the cornea will be weakened and vulnerable during this time. Topical antibiotics and atropine can be discontinued, together with systemic medication. The use of topical lubricants such as carbomer gel should be considered to help tear film dynamics and perhaps provide a little protection to the weakened area. The use of topical NSAIDs is helpful if vascularization is excessive, but topical steroids should probably be avoided if any corneal thinning remains. Normally the vascularization will reduce naturally in 2–4 weeks following epithelialization.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – SURGICAL

If the ulcer is not improving after 48 hours of intensive medical therapy, or if a descemetocoele is present, then surgery is advised. Contact lenses and third eyelid flaps are not usually sufficient to provide adequate corneal support and should not be used if active infection is present. Although corneal glue can be employed, its use is probably best left to specialists. Thus, in practice, the use of conjunctival grafts is probably the best choice. It is important that the surgeon has been taught how to perform these, and has adequate magnification and the correct instrumentation to do so. If not, then referral is recommended.

In general a pedicle conjunctival graft is the most versatile type to use (see Figure 22.4). Details of exactly how to perform this surgery are beyond the scope of this book but the basic technique is as follows:

Figure 22.4 Conjunctival pedicle graft in a Cavalier King Charles spaniel with acute deep corneal ulceration following a scratch by a cat.

Further complications of ulcers are discussed in the next case.

Corneoscleral transposition can be used instead of conjunctival grafts but is best left to specialists since magnification with the use of an operating microscope is essential for accurate surgery.

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis for deep corneal ulcers must always be somewhat guarded. The risk of corneal rupture is present and this can sometimes lead to iris prolapse. There is the risk of bacterial spread into the anterior chamber, resulting in a globe-threatening panophthalmitis. However, with careful management, many cases do very well. Some corneal scarring is inevitable – with both medical and surgical management – but a comfortable, functioning eye can often be the end result. Referral should always be considered for deep ulcers.

The dog was presented with a watery right eye which was held closed. The owners had noticed this a week previously, but had failed to bring the dog to the surgery. Apparently he had been out on a walk and came back holding the eye closed. They assumed that he had banged it but thought that it would get better. No treatment had been given and the dog was reportedly well in himself.

CLINICAL SIGNS

The right eye was unremarkable. The left showed marked blepharospasm and increased lacrimation – the discharge was purely serous. Conjunctival hyperaemia was present, together with marked corneal vascularization extending several millimetres from the limbus towards the central cornea where a deep linear ulcer was noted (Figure 22.6). Slight anisocoria was present (left pupil smaller) but there was no overt uveitis. Schirmer tear test readings were 25 mm in the left eye and 18 mm in the right (in 1 minute). Fluorescein dye stained the walls and base of the ulcer.

WORK-UP

It was explained to the owners that this was a very deep ulcer (probably caused by a foreign body which had fallen out, or a scratch from a bush or similar). Referral for a conjunctival graft was recommended but the owners did not want to pursue this option. No further work-up was undertaken.

TREATMENT

The dog was sedated and a bandage contact lens applied (Figure 22.7). A temporary lateral tarsorrhaphy suture was placed to promote lens retention. Chloramphenicol drops four times daily and once daily atropine drops were dispensed, together with 5 days of carprofen (4 mg/kg/day).

Figure 22.7 The same patient as Figure 22.6 with a bandage contact lens and temporary tarsorrhaphy suture.

OUTCOME

The contact lens was well tolerated and remained in situ. The ulcer could be seen to be healing beneath it. Three weeks after inserting the lens it was removed, along with the tarsorrhaphy suture (which had loosened significantly). The ulcer had fully epithelialized and only a minimal stromal facet remained. The vascularization had reduced. Treatment was stopped. Two weeks later the eye looked fine, with normal vision and minimal scarring.

This case shows that if deep ulcers are sufficiently small and do not become infected, minimal intervention can result in good healing. The dog was young and healthy with no systemic disease which could compromise healing (hypothyroidism for example). Thankfully the delay in presenting the dog did not result in opportunistic infection and the presence of the corneal vascularization suggested that surgery might not be required since healing had already started.