24 Puppy scratched by cat

PRESENTING SIGNS

The young puppy presented due to an encounter with the local cat – sometimes the family cat, sometimes belonging to a neighbour – is a familiar problem in general practice and, as such, it deserves some detailed consideration. The presenting signs are usually textbook classic. The puppy suddenly yelps and holds one eye tightly closed. Meanwhile the cat saunters away unconcerned! The owners present the patient with minimal delay.

CASE HISTORY

As with the case presentation the history is normally very straightforward. The puppy is normally very young – less than 5 months and often only 12–16 weeks. Frequently it has only been in the house for a few days. The puppy was playing and suddenly yelped or screamed and came running away from a cat. It might have encountered the neighbour’s cat in the garden, or cornered the family cat in the kitchen, but the outcome is the same. The cat lashed out at the boisterous puppy and caught it in the eye.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

The most difficult part of the clinical examination is to keep the puppy still for long enough to evaluate it! A general clinical examination should be performed. Occasionally the pup might have other scratch injuries (usually to the face) or it might even become shocked and need immediate attention for this. However, we will assume that it just has an injury to one eye. Full evaluation is required since the trauma could result in simply a very superficial corneal scratch or the far more serious ocular penetration including lens damage.

It is common for the conjunctiva to swell (chemosis) and become markedly hyperaemic, making direct examination of the cornea difficult. The application of topical anaesthesia can help visualization but if the puppy is struggling it is often more sensible to sedate it, or even administer general anaesthesia for a more thorough examination. This is particularly important if a full thickness laceration is suspected – resistance to examination could result in a catastrophic iris prolapse for example. Examination under sedation or anaesthesia obviously has its limitations but it is preferable to exacerbation of the ocular damage. One advantage, however, is that it is possible to fully check the conjunctival sac for remnants of cat claw which could have broken off and if not removed could act as a foreign body later on.

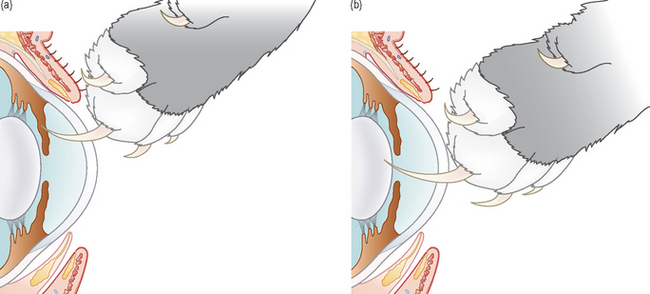

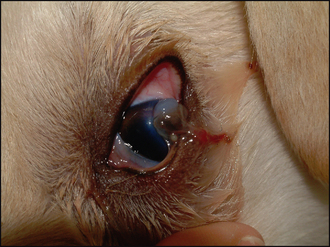

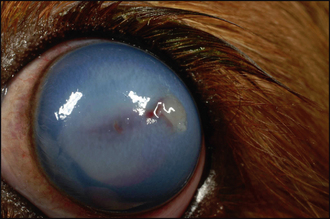

The globe should be evaluated to see if it has been perforated by the cat scratch. The report of a very wet eye, often with a bloodstained discharge, might suggest this (Figure 24.1). Fluorescein can be safely used, even if the eye has been perforated, providing moistened sterile paper strips or single-use vials are used. If the corneal integrity has been broken, a small stream of aqueous might be seen leaking out through the retained dye in the surrounding damaged cornea. Checking the depth of the anterior chamber is useful – it will be shallower than the fellow eye if perforation has occurred. Also the shape of the pupil might alert you to a full thickness injury – normally it would be miotic following the injury but should remain spherical if the cornea is intact. If it is markedly distorted, this suggests corneal rupture with the iris moving forwards to plug the hole (anterior synechia or even iris prolapse) and resultant misshaping of the pupil (see Figure 24.9).

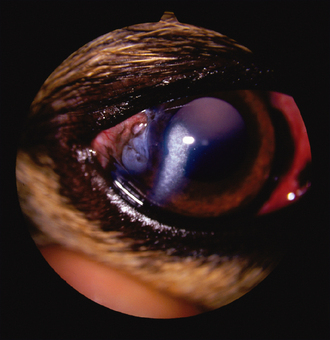

Figure 24.1 Full thickness laceration, resulting in iris prolapse in a 4-month-old Labrador puppy. Note the sticky bloodstained discharge (clotted aqueous) and bulging brown iris with surrounding grey corneal oedema.

Figure 24.9 Iris prolapse in a 4-month-old lurcher which met the neighbouring cat through the fence. Note the dyscoria, bleb of grey–brown tissue on the cornea but lack of haemorrhage or lens damage.

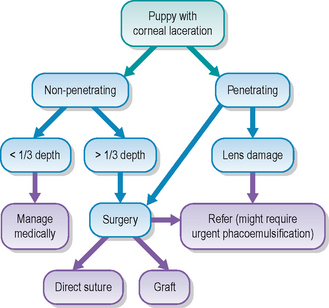

Assuming that the cornea has not been ruptured, the injury can be treated as a superficial or simple deep ulcer. However, cats’ claws often rip through the full thickness of the cornea. If this has occurred, in addition to checking the position of the iris it is essential with any such injury to check the integrity of the lens. Tears in the anterior lens capsule can be catastrophic. If not diagnosed on initial presentation they can result in a serious phacoclastic uveitis, secondary glaucoma and loss of the eye. If the anterior lens capsule cannot be directly visualized, then careful ultrasonography can be considered. However, the ultrasound gel should not be allowed to enter the anterior chamber. If it is not clear whether the lens is involved, then early referral should be considered and offered to the client.

The list of differential diagnoses is minimal since the history and presentation are classic for a cat scratch injury. Other traumatic incidents such as a thorn or even blunt trauma from a football can be considered but the history will usually rule out such events. Progression of an undiagnosed ulcer is possible, but unlikely. Ocular congenital conditions are rarely likely to cause such a presentation with the exception of congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca which could present with a suddenly ruptured corneal ulcer.

CASE WORK-UP

The work-up for a puppy scratched by a cat is minimal. Once the degree of ocular damage has been ascertained, further diagnostics can be undertaken. These might include ultrasonography, as outlined briefly above, to evaluate lens integrity and ensure that the posterior segment is not involved. If the anterior lens capsule has been breached, then early referral should be considered.

Phacoemulsification of the damaged lens offers the best long-term prognosis for the puppy. If the lens appears intact, and immediate referral is not being offered, it might be appropriate to take a swab from the edge of the laceration for bacterial culture and isolation – cats’ claws can harbour a wide range of potentially pathogenic organisms and early detection can allow the most appropriate medication to be chosen. Additional work-up is not usually required.

Some specific nursing factors need considering when dealing with ocular injuries in young puppies. To start with, they will not be fully trained, and so are unlikely to sit on command and keep still for the application of topical medication. As such, it is usually easier if two people are available at treatment times. Self-trauma is more likely in puppies than in older patients and so the use of Elizabethan collars is common. However, many young animals will react quite violently to the collar, and care must be taken to ensure that they do not exacerbate the ocular damage further by thrashing around due to panic and fear of the collar. They should also be kept quiet while the cornea heals – which again is difficult in young playful animals. Nurses can spend time with the owners explaining ways to keep the pet calm without resorting to sedatives!

General aspects of nursing are similar to previous ulcer cases – gently cleaning away any discharge with sterile saline on soft swabs or moist cotton wool prior to the topical application of various medications. The patient should be stroked and fussed after treatment so that they learn that it is not an unpleasant experience and also to distract them such that they are less likely to rub the eye.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The epidemiology of cat scratch injuries is easy to understand when remembering that the menace response is a learned response. It is not innate. The response is not present immediately the eyes open (at about 10–14 days in puppies), but develops gradually by about 4 months of age. Thus, when the playful puppy bounds up to the less than enthusiastic cat, it does not realize that the cat’s paw rapidly reaching out to it is a threatening gesture which is likely to hurt. And in the matter of a few seconds the poor puppy has come off worse from the encounter.

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY REFRESHER

The anatomy of the anterior chamber should be remembered when considering corneal lacerations. Corneal healing has been previously described. If an injury penetrates full corneal thickness and continues into the eye, the damage which follows will depend on whereabouts the injury has occurred. A peripheral laceration will result in the claw catching the iris. This will result in immediate haemorrhage – the anterior face of the iris is highly vascular – but the lens will probably be undamaged (Figure 24.2a). Thus, even if an iris prolapse occurs, the prognosis is probably still reasonable – the uveitis is likely to be moderate. This is assuming that bacterial infection does not complicate the picture.

If the injury has occurred in the central cornea, then the lens is more likely to be involved since anatomically it is the next solid structure for the claw to catch (Figure 24.2b). Once the anterior lens capsule is torn, cortical material leaks out into the anterior chamber. This causes a phacoclastic uveitis – basically the released lens proteins are highly antigenic and cause a tremendous inflammatory reaction which is often poorly responsive to traditional therapy with both steroid and NSAID agents. Removal of the antigenic lens material by phacoemulsification provides the best prognosis if a tear of more than 1 mm has occurred. Pinpoint tears can self-seal, limiting the amount of lens loss and causing a less catastrophic uveitis. In these less serious cases lens removal might not prove necessary.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – MEDICAL

No matter how severe the injury to the puppy’s eye, medical treatment will be required, sometimes alone but sometimes in conjunction with surgery. If the cat scratch is superficial, i.e. no deeper than one-third of the corneal stromal thickness, medical management should suffice. The injury can be treated in the same way as an uncomplicated ulcer. Thus a combination of broad spectrum antibiotic drops such as chloramphenicol four to six times daily in conjunction with topical atropine if any reflex uveitis is present should suffice.

The eye should be checked regularly – every 1–2 days – since although it should heal quickly, it could also deteriorate rapidly. For example, the owner might not be able to medicate effectively resulting in bacterial contamination, or the puppy might not be on restricted play and in its exuberance might knock the already injured eye again such that further damage ensues.

Deeper injuries require immediate systemic antibiotics (e.g. a cephalosporin) and systemic NSAIDs in addition to the topical therapy. Systemic steroids are sometimes used instead of NSAIDs but never without antibiotic cover. The risk of endophthalmitis is present and, as such, aggressive medical management is important.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – SURGICAL

Surgical intervention is often required and it must be decided if referral is in the best interests of the puppy. Certainly if the cornea has been ruptured this should be considered for the best outcome but obviously owner finances, owner commitments and specialist availability will all factor.

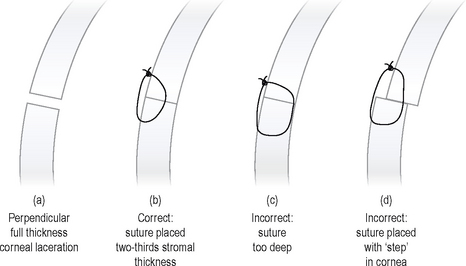

Cat scratch lacerations can be perpendicular to the cornea (these tend to heal more readily) or can be oblique through the stroma. If the former, it is possible to place direct sutures (e.g. of 8/0 polyglactin 910, Vicryl, Ethicon) in a simple interrupted or continuous pattern. This will provide immediate support to the weakened area and promote rapid healing. Prior to any surgery the application of several doses of topical antibiotic, plus atropine and possibly a topical NSAID (or certainly a systemic one), should be undertaken. Careful surgical preparation is required and while under anaesthesia it is important to check that no fragments of claw have become embedded in the conjunctiva or fornix. The placement of the sutures is important: they should extend from one-third to halfway through the stroma – never full thickness – and should be tightened to allow the edges of the cornea to meet smoothly with no stepping at the surface of the wound (Figure 24.3). Postoperative care is as mentioned above under medical management. Once the wound has healed, i.e. no fluorescein is retained between the sutures and the cornea lies flat around them, it might be necessary to introduce a topical anti-inflammatory agent (such as dexamethasone alcohol or prednisolone acetate) to reduce the likely vascular reaction associated with the sutures starting to dissolve. This reaction can be quite florid in young, growing animals and is often a cause of concern for the owner.

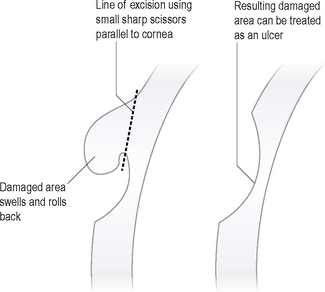

For a laceration which is not full thickness but is an oblique cut, it is possible to trim the oedematous loose flap of cornea under general anaesthesia with small, sharp scissors (Figures 24.4 and 24.5). This will prevent the devitalized flap from acting as a site for collagenase release which could then lead to corneal melting (discussed in Chapter 23). Removing the loose flap will result in a larger stromal defect such that direct suturing is not possible to close this gap. The injury can be treated as a simple but fairly deep ulcer and allowed to heal without further surgery. However, the cornea will be weakened and, as previously alluded to, the patient might not be quite as cooperative as an older animal with respect to keeping calm and not leaping about and getting over-excited. As such, further protection with the use of a conjunctival graft might be prudent. Not only would this provide a blood supply with nutrients, anticollagenases and so on, it would also provide the all-important structural support. Additionally, it is possible to carefully use topical steroids immediately following graft placement should a significant uveitis be present.

Figure 24.4 Oblique corneal laceration resulting in flap of cornea seen as grey ‘blob’ on the front of the eye. This must be differentiated from clotted aqueous. The dog is an older Jack Russell terrier which met an unfriendly cat (rather than a puppy)!

Serious injuries with iris prolapse should be referred unless magnification and experience are available! It is necessary to evaluate the iris and decide if it can be replaced or if it requires amputation. The anterior chamber is usually inflated with viscoelastic agents to assist the surgery and help to evaluate the lens. If the lens capsule has been damaged, the surgeon must decide if the lens needs removal. Phacoemulsification at the same time as corneal repair is often required in these situations. If the lens damage has not been appreciated initially and the cornea has been repaired, only to find a few days later that the eye is becoming very inflamed with white matter in the anterior chamber (a combination of released lens material which has become cataractous together with hypopyon), then referral at this stage is important if the eye is to have any chance of being salvaged. The specialist is likely to need to operate quickly in order to remove all the damaged lens and carefully flush the anterior chamber. However, once a phacoclastic uveitis has developed, the prognosis is guarded. There is often an overwhelming inflammatory reaction, which, even with surgery, and high dose topical and systemic steroids, cannot be fully controlled and leads rapidly to a secondary glaucoma. In these cases enucleation is then the only option. In addition to the inflammatory reaction which develops following ocular penetration, we must remember that the cat claw could have inoculated bacteria into the anterior segment. These can rapidly multiply resulting in a panophthalmitis and loss of the globe though infection.

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis for an eye that has been lacerated by a cat will clearly depend on the degree of damage present (Figure 24.6). However, the owners should be fully aware of the serious nature of the injury from the start. Superficial damage does carry a good prognosis and lesions heal with minimal scarring. Although those which require surgery will result in more scarring, providing the injury was not full thickness the prognosis is still reasonable. If a full thickness injury has occurred, but with minimal lens damage, some animals can still do very well and retain functional vision (Figure 24.8). It is those cases in which corneal rupture has occurred that carry a poor outlook. The presence of an iris prolapse, severe hyphaema and collapse of the anterior chamber require specialist surgery and even then the inflammation which ensues can be difficult to control. It is not usually the corneal injury which provides the problems, but the reaction of the uveal tract. The blood–aqueous barrier in young animals is unstable and more labile than in adults, resulting in a more rapid and severe inflammatory reaction. A tear in the anterior lens capsule, especially if more than 1–2 mm in size, will result in the release of lens cortex into the anterior chamber. This material is highly antigenic and a tremendous uveitis can follow which triggers a painful, blinding secondary glaucoma. Removing the eye is then the only option.

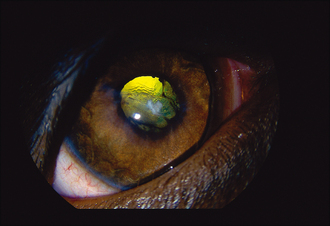

Figure 24.8 Young Labrador which was scratched by a cat 6 months previously. The corneal laceration was small and healed without surgery. Note the anterior capsular and cortical cataract and wrinkling of the anterior lens capsule, together with mild posterior synechia formation. However, the iris looks fine with no ongoing uveitis and the eye is visual. A large tear in the lens capsule could have been catastrophic.

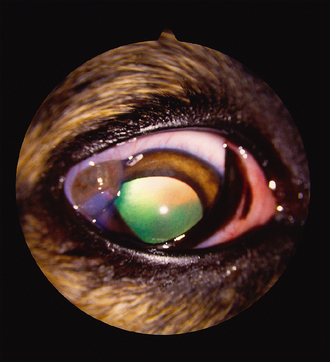

Figure 24.7 Cavalier King Charles spaniel puppy which was scratched by a cat 12 hours previously. Note the corneal laceration and bleb of clotted aqueous sitting on the cornea, marked corneal oedema and hyphaema. The lens was ruptured and emergency phacoemulsification was required.

Image courtesy of Christine Heinrich, Willows Referral Centre, Solihull, West Midlands.

Owners should also be aware that even if the puppy does well in the short term, the longer term prognosis is still guarded. It is not uncommon for the wound to heal well, the inflammation to settle and the puppy come off all treatment, only to suffer from glaucoma several months later.

CLINICAL SIGNS

The puppy was frightened but otherwise well. Only the right eye was affected. A watery discharge was present. A large bleb was noted laterally close to the limbus. It was the same colour as the iris but appeared slightly gelatinous. This was an iris prolapse. Minimal conjunctival hyperaemia was noted. Dyscoria was present with the pupil drawn out laterally towards the corneal injury (Figure 24.9). Vision was present and the lens appeared undamaged.

TREATMENT

General anaesthesia was induced and the injury was examined and found to be adjacent to the limbus, but not crossing it. The iris was flushed with sterile saline, the fibrin removed from it and it was gently replaced through the corneal wound. This was then directly repaired, and a small advancement conjunctival graft was sutured over the top for added security (given the lively nature of the puppy!). All sutures were 8/0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl, ethicon). Postoperatively he was treated with a week of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid tablets, chloramphenicol drops six times daily, atropine drops twice daily and prednisolone acetate four times daily, all for 2 weeks, and then continued with just prednisolone acetate at reducing levels for the following 6 weeks.

OUTCOME

Healing of the corneal wound and graft was uneventful and minimal uveitis developed. The graft pulled slightly a month following surgery but by this stage the cornea was fully healed. A lipid keratopathy developed adjacent to the injury – probably as a combination of altered blood supply to the area exacerbated by the topical steroids (Figure 24.10). However, this was not in the visual axis and remained of no concern to the dog.

Figure 24.10 Same lurcher as in Figure 24.9, 3 months later. Note the lateral corneal scar and slightly pulled corneal graft, plus the arc of corneal lipidosis. The visual axis is clear and vision is normal.

This case illustrates that with rapid presentation and immediate surgery such injuries can do very well. The lack of haemorrhage and lens damage certainly contributed to the successful outcome.