32 The Head and Ventral Neck of the Pig

The way in which most pigs are reared today results in veterinary attention being concentrated on infectious diseases and other matters affecting the herd rather than on conditions affecting the individual animal. The short life span generally allowed to pigs makes many interventions uneconomic. For example, most pigs are slaughtered at 5 or 6 months, and even breeding stock is culled when only a few years old. In addition, clinical examination may be difficult because of the thick layer of subcutaneous fat (panniculus adipose) and possibly hazardous because of the frequently aggressive disposition of older animals. A wide knowledge of the anatomy is therefore less necessary than it is for those dealing with most other species. The employment of pigs, sometimes the “mini” variety, in biomedical research supplies exceptions to the previous statement, but the specialized requirements in such contexts are beyond the scope of this book.

CONFORMATION AND SUPERFICIAL FEATURES

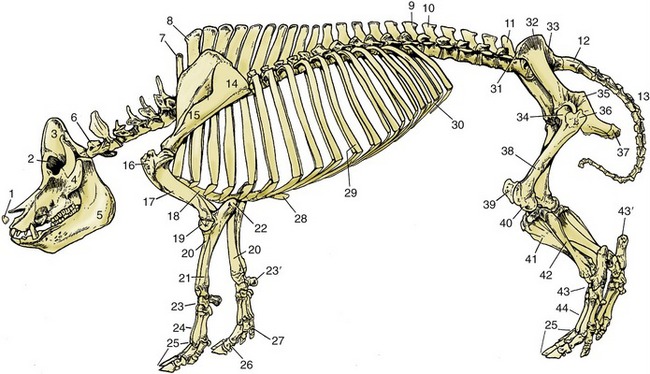

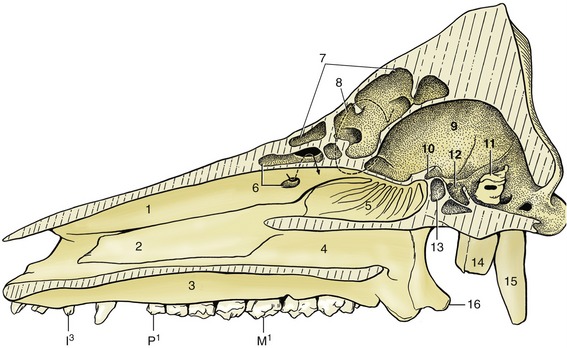

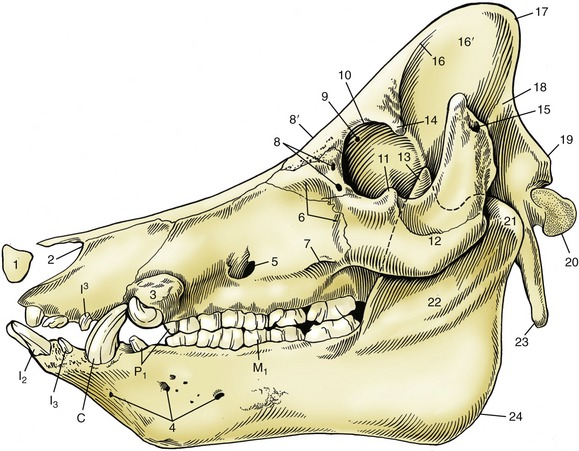

The head and neck together form a cone that blends with the trunk at the level of the forelimbs. The skull of primitive breeds, as of the ancestral wild form, is more or less pyramidal, but that of most improved breeds sweeps sharply upward to a prominence that rises well above the brain (Figure 32–1). The dorsal surface of the cranium is bounded caudally by a thick nuchal crest and demarcated from the temporal fossa to each side by a prominent temporal line that continues into the zygomatic process of the frontal bone. This process, relatively short, fails to meet the zygomatic arch, which completes the margin of the small orbit (see Figure 32–8). The arch is extremely sturdy and carries the wide, flat articular surface and, more rostrally, the depression from which the levator labii superioris arises.

Figure 32–1 Skeleton of a pig. 1, Rostral bone; 2, orbit; 3, temporal fossa; 4, zygomatic arch; 5, mandible; 6, first cervical vertebra; 7, last cervical vertebra (C7); 8, first thoracic vertebra; 9, last thoracic vertebra (T16); 10, first lumbar vertebra; 11, last lumbar vertebra (L5); 12, sacrum; 13, caudal vertebrae; 14, scapula; 15, spine of scapula; 16, greater tubercle of humerus; 17, humerus; 18, sternum; 19, condyle of humerus; 20, radius; 21, ulna; 22, olecranon; 23, carpal bones; 23′, accessory carpal bone; 24, metacarpal bones; 25, phalanges; 26, phalanges of principal digit; 27, phalanges of accessory digit; 28, xiphoid cartilage; 29, tenth pair of ribs; 30, costal arch; 31, coxal tuber; 32, iliac crest; 33, sacral tuber; 34, head of femur in acetabulum; 35, ischial spine; 36, greater trochanter; 37, ischial tuber; 38, femur; 39, patella; 40, lateral condyle of femur; 41, tibia; 42, fibula; 43, tarsal bones; 43′, calcaneus; 44, metatarsal bones.

On the basal surface, the cranial and choanal regions of the skull are dorsal to the plane of the palate. The large paracondylar processes and tympanic bullae are prominent features of the cranium. The body of the stout, rather rectilinear mandible is cut away in adaptation to the rooting habit. The mandibular symphysis ossifies at about 1 year.

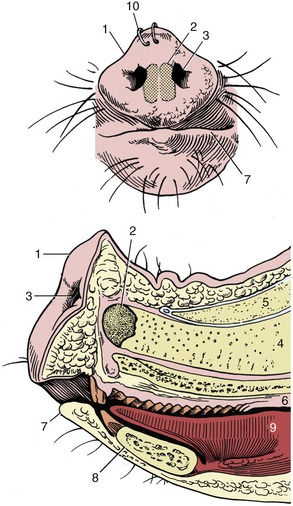

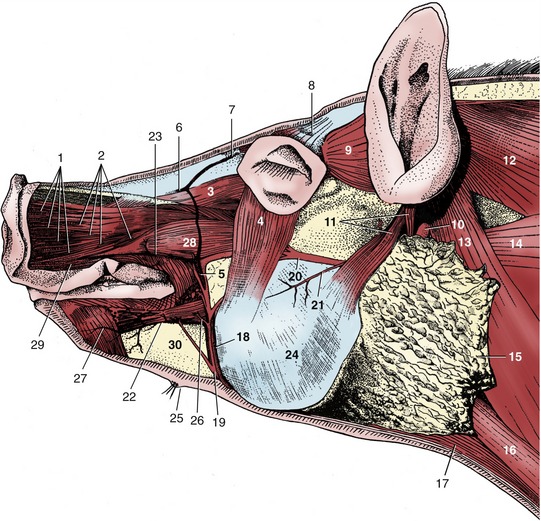

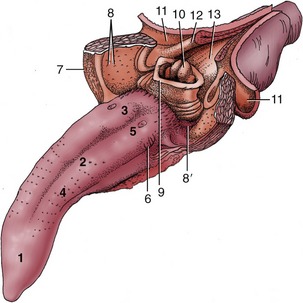

The most striking feature of the head is the rostrum, or snout, the disklike and mobile tip of the muzzle that incorporates the middle part of the upper lip and is perforated by the rounded nostrils (Figure 32–2). The snout is supported by a small rostral bone set against the end of the nasal septum that gives attachment to the levator labii superioris (Figure 32–3/3), the muscle principally concerned with movements of the snout. Pigs allowed access to open ground are generally “ringed” through the upper margin of the snout to discourage the rooting habit, a practice more frequently required in former times than today. The lips are short and rather immobile; the upper one is notched to accommodate the projecting canine tooth (tusk).

Figure 32–2 The snout from the front and in median section. 1, Rostral plate; 2, rostral bone; 3, nostril; 4, nasal septum; 5, nasal bone; 6, hard palate; 7, lower lip; 8, mandible; 9, tongue; 10, nose rings to discourage rooting.

Figure 32–3 Head, superficial dissection. 1, Cut fasciculi of levator nasolabialis; 2, caninus; 3, levator labii superioris; 4, malaris; 5, facial vein; 6, dorsal nasal vein; 7, frontal vein; 8, levator anguli oculi; 9, frontoscutularis; 10, lateral retropharyngeal lymph node; 11, parotidoauricularis; 12, trapezius; 13, cleidooccipitalis; 14, omotransversarius; 15, parotid gland; 16, sternocephalicus; 17, sternohyoideus; 18, parotid duct; 19, 20, ventral and dorsal buccal branches of facial nerve; 21, transverse facial nerve; 22, inferior labial vein; 23, superior labial vein; 24, masseter; 25, mental hairs and gland; 26, depressor labii inferioris; 27, mentalis; 28, depressor labii superioris; 29, orbicularis oris; 30, mandible.

The small eyes are deeply placed and, uniquely among domestic species, lack a tapetum lucidum and are not therefore reflective of light. A deep lacrimal gland is associated with the third eyelid in the ventromedial angle of the orbit. Together with the retrobulbar muscles, it is engulfed by an orbital venous sinus that may be punctured at the medial angle of the eye by directing a needle medioventrally, between the globe and the third eyelid. The procedure is most likely to be performed in a research context. The sinus is said to be involved in thermoregulation of brain temperature by conveying cool blood from the nasal cavity.

The oval ears are attached to the high caudal part of the head and in lop-eared breeds hang down over the face. The external surface displays the only veins convenient for intravenous injection. These may be readily visible but, if not, are made so by application of a tourniquet at the base of the ear. The lateral vein of the set is most often used. Chewing of their companions’ ears is a common vice among young pigs raised together in close quarters.

Subcutaneous injections are commonly made at a site just caudal to the ear; awareness of the proximity of the parotid gland is necessary (Figure 32–3/15). The same site is used for injection into the muscle mass directly caudal to the skull; however, the orientation of the needle is different.

The neck is roughly cylindrical but with some lateral compression. It is remarkably short; the closeness of the angle of the mandible to the shoulder joint prevents the animal from turning its head to any great degree. The flabby lateroventral parts of the neck, the jowls, are common seats of abscesses.

The more important superficial structures of the head are shown in Figure 32–3. They include the buccal branches of the facial nerve (Figure 32–3/19,20); the ventral one follows a course around the lower margin of the masseter in company with the parotid duct and the facial artery and vein. The artery is short because the dorsal part of the face is supplied by the infraorbital artery that reaches the scene through the infraorbital foramen together with the nerve of the same name. The facial vein is partly formed by a frontal tributary that becomes superficial by emerging through the foramen dorsomedial to the orbit. As would be expected, the infraorbital nerve is large because it supplies the sensitive snout.

THE NASAL CAVITY AND PARANASAL SINUSES

The deep nasal cavities extend well behind the level of the orbits (Figure 32–4). Despite the widening of the face, they remain narrow because they are separated from the lateral surface of the head by the thick muscles of facial expression and by fat, not by paranasal sinuses, as in cattle and horses. Two conchae divide each cavity into the usual system of meatuses. The dorsal meatus leads to the fundus, which lies dorsal to the nasopharynx, and is largely occupied by the ethmoidal conchae, which are covered by olfactory mucosa. This is extensive in a species endowed with a sense of smell sufficiently acute to be exploited in the search for buried truffles.

Figure 32–4 Paramedian section of the skull. 1, Dorsal turbinate bone, fenestrated at 6 to show conchal sinus; 2, ventral turbinate bone; 3, hard palate; 4, choana; 5, ethmoturbinates in fundus of nasal cavity; 6, conchal sinus; 7, portion of frontal sinus exposed by paramedian saw cut; 8, position of orbit; 9, cranial cavity; 10, optic canal; 11, petrous temporal bone; 12, fossa for hypophysis; 13, sphenoid sinus; 14, tympanic bulla; 15, paracondylar process; 16, hamulus of pterygoid bone.

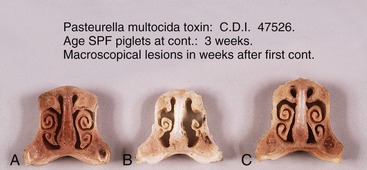

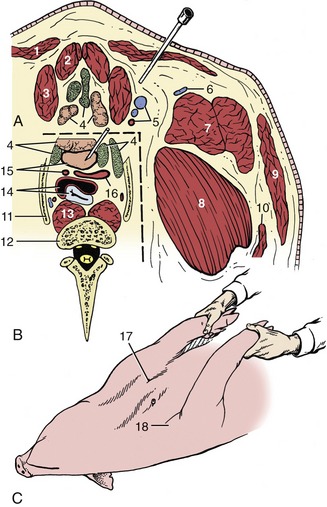

The dorsal concha is a thick plate projecting from the dorsolateral wall of the cavity (Figure 32–5). The ventral concha, though shorter, is more complicated and consists of upper and lower scrolls arising in common from a lateral plate. Familiarity with the conformation of these conchae is necessary if the deformity that develops in atrophic rhinitis, a common debilitating disease of young pigs, is to be recognized (Figure 32–5).

Figure 32–5 Transverse sections of the nose of piglets treated with the toxin causing atrophic rhinitis; in A the piglet is treated with a low dose. In B the piglet is treated with an activated dose, and in C the piglet is treated with an inactivated dose.

The paranasal sinus system is complicated and comprises frontal, maxillary, lacrimal, spheniodal, and conchal units, but not all of these merit attention (see Figure 32–4). The maxillary sinus, level with the orbit, extends into the base of the deep zygomatic arch. The frontal sinuses of the mature pig excavate the entire dorsal surface of the skull caudal to the nasal bones. They spread the outer and inner plates of the cranial roof so widely apart that all correspondence between the external form and the cranial cavity is lost (Figure 32–4/7). The brain thus lies at a depth of about 5 cm below the skin, protected by two plates of bone. Although it is speculated that this construction may have developed in response to the rooting habit, it has the consequence that pigs cannot be reliably stunned by mechanical means (hammer or captive bolt), and humane slaughter requires the use of electrocution or carbon dioxide gas, which are the methods commonly employed today. When shooting is employed, the target site must be carefully chosen; for most pigs it is the intersection of the diagonal lines connecting the eyes with the bases of the opposite ears (Figure 32–6). In particularly large pigs, it is more satisfactory to shoot through the occipital bone from behind.

THE MOUTH AND DENTITION

The animal’s inability to open its mouth widely and problems with restraint make it difficult to examine the long and narrow mouth of the conscious animal. The ridges of the roof of the rostral part of the cavity end abruptly at the boundary of the soft palate, where the two discrete tonsils of the soft palate, which correspond to the tonsils embedded in the lateral walls of the oropharynx of other species, are found. These tonsils are cut in routine meat inspection.

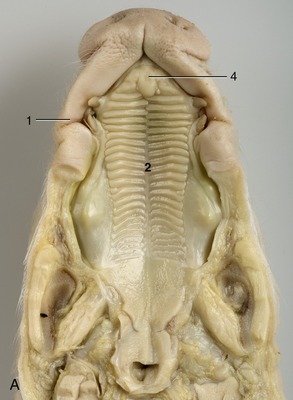

The pointed tongue occupies the floor. In the newborn, the tongue is fringed with lacelike marginal papillae (Figure 32–7/3), which persist for the first 2 or 3 weeks of life; because they swell visibly preparatory to contact with the teat, they are believed to help seal the mouth about the teat when sucking.

Figure 32–7 The roof (A) and the floor (B) of the mouth of a newborn piglet. 1, Permanent notch in upper lip opposite tusk; 2, hard palate with ridges; 3, lingual marginal papillae; 4, incisive papilla.

Pigs have the most complete dentition of any domestic animal (see Figure 3–18); the formula for the permanent dentition is

The straight lower incisors meet the curved upper incisors to provide a potential grasping action (Figure 32–8). The curved canine teeth, or tusks, are firmly embedded in the jaws. In boars the roots remain open, and the tusks grow throughout life, providing these animals with formidable weapons; however, in sows growth ceases after 2 years and their smaller tusks do not project from the mouth. The tusks of boars are often cut short, sometimes without benefit of anesthesia. The crowns of the check teeth increase in both length and breadth from first to last in the series. The occlusal surfaces of the molars show many irregularities and are ideally adapted for crushing food.

Figure 32–8 Skull of a boar. 1, Rostral bone; 2, nasoincisive notch; 3, canine eminence; 4, lateral mental foramina; 5, infraorbital foramen; 6, fossa canina; 7, facial crest; 8, lacrimal foramina; 8′, location of supraorbital foramen on dorsal surface; 9, orbital end of supraorbital canal; 10, orbital rim; 11, frontal process of zygomatic bone; 12, zygomatic arch; 13, coronoid process of mandible; 14, zygomatic process of frontal bone; 15, external acoustic meatus; 16, temporal line; 16′, temporal fossa; 17, nuchal crest; 18, temporal crest; 19, nuchal tubercle; 20, occipital condyle; 21, condylar process of mandible; 22, ramus of mandible; 23, paracondylar process; 24, angle of mandible; I2, I3, I3, incisors; C, canine teeth (tusks); P1, first premolars; M1, first molar.

Table 32–1 summarizes the ages at which different teeth erupt and are replaced. The deciduous incisors and canines with which the piglet is born are known as needle teeth. They project laterally from the gums and, being very sharp, may injure the mother’s teat or any littermate in competition for this. They are therefore commonly nipped off within hours of birth; the procedure requires some care if the marginal lingual papillae are not to be injured. The dentition is normally complete by the age of 18 months, long after sexual maturity is reached.

Table 32–1 Eruption Dates of Porcine Teeth

| Temporary Tooth | Permanent Tooth | |

|---|---|---|

| Incisor 1 | 1–3 wk | 11–18 mo |

| Incisor 2 | 8–12 wk | 14–18 mo |

| Incisor 3 | Before birth | 8–12 mo |

| Canine | Before birth | 8–12 mo |

| Premolar 1 | 4–8 mo | |

| Premolar 2 | 6–12 wk | 12–16 mo |

| Premolar 3 | 1–3 wk | 12–16 mo |

| Premolar 4 | 2–5 wk | 12–16 mo |

| Molar 1 | 4–8 mo | |

| Molar 2 | 7–13 mo | |

| Molar 3 | 17–22 mo |

The large parotid gland lies ventral to the base of the ear (see Figure 32–3/15). It extends only a little way over the masseter muscle rostrally, but its cervical angle reaches beyond the middle of the neck under cover of the cutaneous muscle; it has numerous relations to the structures within the visceral space of the neck. Its duct crosses the mandibular gland and curves around the ventral border of the mandible to gain the face and open into the buccal cavity. The smaller rounded mandibular gland lies partly medial to the mandible, partly deep to the parotid. Its duct runs alongside the sublingual gland to open at the sublingual caruncle. Both parts of the sublingual gland are present; they drain in the usual way.

THE PHARYNX

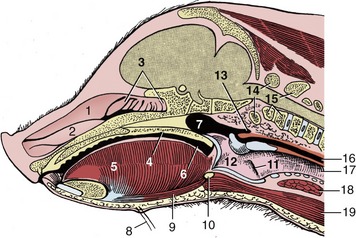

The only feature of this organ to require notice is the presence of a diverticulum that burrows into the pharyngeal muscles dorsal to the entrance to the esophagus (Figure 32–9/13). The diverticulum is about 1 cm long in the piglet and grows to about 3 or 4 cm in the adult. It appears to be without functional significance but is of practical importance because it is vulnerable to injury when a pig is dosed with a syringe. Should the diverticulum be perforated, the medication will be deposited in the tissues of the neck, with damaging effect. In the piglet of 4 weeks the diverticulum is level with the rostral part of the base of the ear, and about 2.5 cm caudal to the intended site of deposition is the oropharynx; a useful guide to the appropriate level is provided by the lateral angle of the eye.

Figure 32–9 Median section of the head of a 4-week-old pig; the nasal septum has been removed. 1, Dorsal nasal concha; 2, ventral nasal concha; 3, ethmoidal conchae; 4, soft palate; 5, tongue; 6, oropharynx; 7, nasopharynx; 8, mental hairs; 9, geniohyoideus; 10, basihyoid; 11, laryngeal ventricle; 12, larynx; 13, pharyngeal diverticulum; 14, atlas; 15, axis; 16, esophagus; 17, trachea; 18, thyroid gland; 19, sternohyoideus.

The disposition of tonsils in the pig (Figure 32–10) may appropriately be summarized here. A paraepiglottic tonsil is situated rostrolateral to the base of the epiglottis (Figure 32–10/8′); a pharyngeal tonsil is found on the roof of the pharynx; tubal tonsils are associated with the pharyngeal openings of the auditory tubes; and there are the tonsils of the soft palate already mentioned (Figure 32–10/8). The first and last of these are sometimes examined at meat inspection, on the pluck (tongue, larynx, trachea, esophagus, heart, and lungs) and on the cut surface of the head, respectively.

Figure 32–10 Tongue and pharynx. The soft palate and the dorsal wall of the esophagus have been split in the midline. 1-3, Apex, body, and root of tongue; 4, fungiform papillae; 5, vallate papillae; 6, foliate papillae; 7, palatoglossal arch; 8, tonsil of the soft palate; 8′, paraepiglottic tonsil; 9, epiglottis; 10, corniculate processes of the arytenoid cartilages; 11, dorsal wall of nasopharynx; 12, palatopharyngeal arch; 13, entrance to esophagus.

THE LARYNX

The most important feature of this organ is the obtuse angle it forms with the trachea (Figure 32–9/12,17). Both this and the presence of lateral ventricles in the larynx (Figure 32–9/11) have been cited as the causes of the difficulty that may be experienced when intubation is attempted for the induction of inhalation anesthesia; the procedure is most likely to be indicated in research settings. The larynx lies caudal to the intermandibular space, and its prominence may be palpated in the middle of the neck.

THE VENTRAL ASPECT OF THE NECK

The visceral space of the neck has the same contents as in other species and is similarly enclosed ventrolaterally by a series of thin, straplike muscles. The cutaneous muscle is thick at its origin from the manubrium but thins when followed cranially to merge with the cutaneous muscles of the face. A more important impediment to puncture of the external jugular vein is the thick subcutaneous fat.

The trachea and esophagus show no unusual features nor do the vessels and nerves passing between head and thorax, apart from the internal jugular vein, which is considerably better developed than in most other species. The thyroid gland consists of two lobes, broadly connected ventral to the trachea; because of the shortness of the neck, it lies close to the thoracic inlet (see Figure 6–4, D). The thymus lies to each side of the larynx and trachea (Figure 32–11/3,4) and is particularly well developed: it does not attain its greatest size until the animal is about 9 months old and begins to regress a few months later. Its bulbous cranial extremity carries on its surface the minute (1 to 4 mm) external parathyroid glands. (The internal parathyroid glands are thought to disappear in the embryo.)

Figure 32–11 Ventral view of the neck. Deep dissection to the right; superficial dissection, from which the cutaneous colli has been removed, to the left; semischematic. 1, Parotid gland; 2, mandibular gland; 3, thymus—dot on cranial end indicates the position of the external parathyroid; 4, thyroid; 5, external jugular vein; 6, cephalic vein; 7, sternohyoideus (drawn narrower than actual width); 8, internal jugular vein; 9, larynx; 10, manubrium sterni; 11, superficial pectoral muscle; 12, brachiocephalicus; 13, subclavius; 14, sternocephalicus; 15, omohyoideus; 16, angle of mandible; 17, mylohyoideus; 18, basihyoid; 19, mandibular lymph nodes.

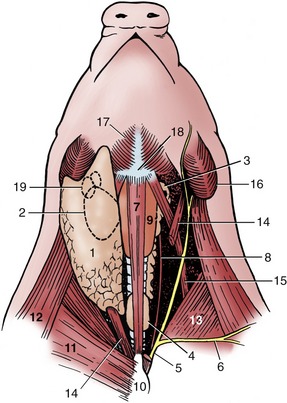

The most common clinical procedure involving the neck is cranial vena cava puncture, which may be performed in the standing animal or in one suitably restrained on its back. The needle is inserted in the depression between the manubrium and the point of the right shoulder and advanced in the direction of the left scapula until it meets one or other of the large veins between or just in front of the first pair of ribs. Entry is best made from the right because the left phrenic nerve is more vulnerable to injury; the thoracic duct also lies more to that side (Figure 32–12).

Figure 32–12 A, Transverse section of the ventral neck slightly cranial to the manubrium sterni. B, The area within the broken line represents the topography at the slightly more caudal level of the first ribs. C, Pig held on its back for cranial vena cava venipuncture; see needle in position. 1, Cutaneous colli; 2, sternohyoideus; 3, sternocephalicus; 4, lymph nodes and thymus; 5, common carotid artery and external and internal jugular veins; 6, cephalic vein; 7, brachiocephalicus; 8, subclavius; 9, platysma; 10, omotransversarius; 11, first rib; 12, body of C7; 13, longus colli; 14, trachea and esophagus; 15, cranial vena cava and left subclavian artery; 16, bicarotid trunk and right subclavian artery; 17, palpable manubrium sterni; 18, shoulder joint.

THE LYMPHATIC STRUCTURES OF THE HEAD AND NECK

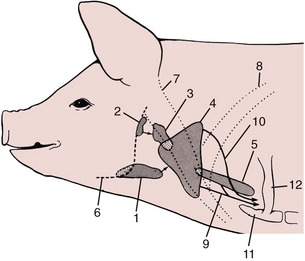

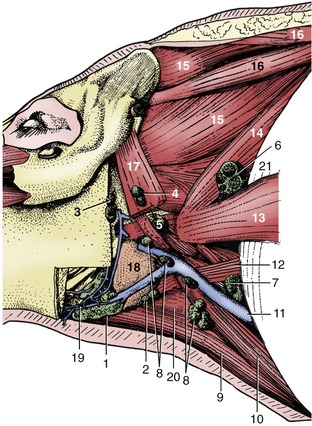

Five lymph centers are located in the head and ventrolateral part of the neck (Figure 32–13). The mandibular center comprises about six principal and four accessory nodes. The mandibular nodes lie behind the caudoventral border of the mandible, related to the mandibular gland and crossed laterally by the facial vein (Figure 32–14/1). They drain the ventral half of the head and forward lymph to the accessory group and to ventral and dorsal superficial cervical nodes and are routinely examined in meat inspection. The accessory nodes (Figure 32–14/2) are also located by the border of the mandible and under cover of the parotid gland. They drain the same part of the head and also the ventral part of the neck; their efferents also go to the superficial cervical nodes. The parotid nodes (Figure 32–14/3) are located ventral to the temporomandibular joint covered by the parotid gland. They drain the head dorsal to the palate and send their efferents to the lateral retropharyngeal nodes (Figure 32–14/4).

Figure 32–13 The lymph centers of the head and neck, schematic. The arrows indicate lymph flow. 1, Mandibular lymph center; 2, parotid lymph center; 3, retropharyngeal lymph center; 4, superficial cervical lymph center; 5, deep cervical lymph center; 6, mandible; 7, brachiocephalicus; 8, subclavius; 9, tracheal lymph trunk; 10, lymph from dorsal superficial cervical nodes; 11, manubrium sterni; 12, first rib.

Figure 32–14 Dissection of the neck to show the lymph nodes, left lateral view. 1, Mandibular lymph nodes; 2, accessory mandibular lymph nodes; 3, parotid lymph nodes; 4, lateral retropharyngeal lymph nodes; 5, medial retropharyngeal lymph nodes; 6–8, dorsal, middle, and ventral superficial cervical lymph nodes; 9, sternohyoideus; 10, sternocephalicus; 11, external jugular vein; 12, omohyoideus; 13, omotransversarius; 14, serratus ventralis cervicis; 15, splenius; 16, rhomboideus cervicis et capitis; 17, cleidomastoideus; 18, mandibular gland; 19, facial vein; 20, thyrohyoideus; 21, subclavius.

The retropharyngeal center consists of one medial and two lateral nodes (Figure 32–14/4,5). The latter lie near the joint, again under the parotid gland and a few centimeters caudal to the parotid center. They drain superficial structures where the head joins the neck; their efferents go to the dorsal superficial cervical nodes. The medial node lies above the pharynx and drains deeper structures at the same level as the lateral nodes; its efferents join to form a tracheal duct.

The superficial cervical center consists of about 10 nodes, roughly arranged in a triangle and divided into dorsal, middle, and ventral groups (Figure 32–14/6-8). Together, they correspond to the single group found deep to the omotransversarius in other species. The dorsal nodes drain the neck and neighboring parts of the thoracic wall and forelimb. They also receive lymph from the head nodes, other than the medial retropharyngeal, and pass it to veins at the thoracic inlet. The middle group is dorsal to the external jugular vein and drains the shoulder region; its efferents accompany or join those of the dorsal group. The ventral group is arranged in a chain and, like the middle nodes, lies deep to the brachiocephalic muscle. It drains superficial structures of the neck, the forelimb, the ventral thoracic wall, and the first two mammary glands. It also receives lymph from the mandibular and lateral pharyngeal nodes.

In theory, the many nodes of the deep cervical center are divided into several groups spread at intervals along the internal jugular vein. In practice, few are usually to be found. They drain directly to the large veins at the thoracic inlet.